Exploring Mawaru Penguindrum (2011) from a Historical, Cultural and Literary Perspective

Mawaru Penguindrum (2011) unfortunately falls into the strange category that contains the likes of Shinsekai Yori (2012): anime that are masterpieces, but are not as well-known as they should have been. Some of the clues to fully understanding the anime might also be lost in translation, resulting in Western audience scratching their heads, blinking in confusion, or just dismissing the show as nothing more than being intriguing and entertaining. The purpose of this article, hence, is to introduce elements relating to Japanese history, culture and literature that are essential to understanding the greatness of this overlooked piece of gem.

**Warning: major spoilers ahead**

Nowhere men: the birds that can’t fly

Before we get into the historical context, it is important to keep the symbolism of penguin in mind, as this relates to our further discussion. In an interview, director Kunihiki Ikuhara explains:

“They have wings but they cannot fly; they can swim but they cannot stay underwater for too long. In that case, where do they really belong? They’re not common animals (mammals) like cats and dogs. They’re birds that don’t look like birds at all. The idea that they seem to have come from another world and have no place of belongings ignite his imagination.”

The penguins can be seen as a reflection of the characters’ loss of identity in the anime, be it Kanba’s struggle to hold his family (whether his real or surrogate one) together, Shouma’s struggle with his interpersonal relationship (his guilt of being close to Ringo, knowing that his family was the reason behind her family’s dysfunction), Himari’s conflict of her haunting past and her present dilemma, or Ringo’s struggle between living as Momoka or as herself. Like penguins, they struggled to find a place that they could feel at ease. Common sense entails that the place was ‘home’, or ‘family’, but where could you go when your family was the very the reason why you were trapped in the past?

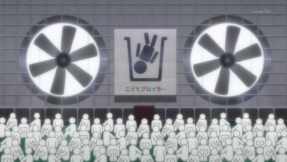

The penguins were omnipresent in the anime. They were spotted on various company or investigation team logos, as if saying that everything was under the same chain. One might wonder if this also meant that the whole society was monopolized by one big organization. Figuratively, it might also be a critique of the capitalist society, where a number of big organizations are actually in control of our everyday life. It isn’t uncommon for writers to write about one’s sense of alienation and loss of identity in a capitalist world (cue Haruki Murakami – which I will discuss later). The subtle critique of capitalism, especially in post-war Japan, casts a frightening image of the cute-looking penguin.

In another way, the penguins in the show indicated what their owners were like, for purposes of both comedic reliefs and reflection of the owner’s personality. Penguin#1, for example, liked to look up ladies’ skirts and read adult magazines, reflecting Kanba’s reputation of being a playboy. Penguin#2 was always seen killing cockroaches and eating food. The former seemed to be suggesting Shouma’s preference for cleanliness, much like his personality in the show. The latter, however, was more thought-provoking. A bold guess might be that it related to the time when he was trapped in the cage and was suffering from hunger (before Kanba offered him half an apple), hence Penguin#2 showed no hesitation in consuming any food that it spotted as an automatic response. Penguin#3 fit Himari’s personality of being a ‘good girl figure’ of the show – a quiet, gentle being that was seen knitting and cooking with Himari many times. The penguins, hence, could be seen as what the characters were really thinking, despite the fact that their actions might entail otherwise. There is not much to discuss further, however, since there weren’t many clear clues on what the penguins’ roles really were.

20th March, 1995 – The Day that was Promised

This particular date kept repeating itself throughout the whole anime. Viewers learn that it was the day that Kanba, Masako, Shouma and Ringo were born. We also learn that it was the day Shouma’s father executed the attack that was the backdrop of the whole series. However, if you ask any Japanese about this particular date, they would likely tell you that it was the date the whole nation could never forget, the incident that became known as the ‘Subway Sarin Incident‘.

On 20th March, 1995, members of the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo, under the order of their leader Asoko Asahara, released sarin gas in five subway lines in Tokyo, killing thirteen people and injuring a thousand more. This incident was the single most serious attack to have taken place in Japanese soil since World War II, adding further despair to the Japanese people who were experiencing the Lost Decade (1990s Japan) after the economic bubble burst in late 1980s.

The motive behind this attack was rather bizarre. Aum Shinrikyo, established in 1984 and promoted values combining yoga, Buddhism and Christianity (though it acted more like a personal cult of Asahara), had been linked to several high-profile murder cases before. Having received news that the police would raid Aum Shinrikyo’s headquarters on 22nd March, Asahara and several top members decided to plant a sarin gas attack on 20th March in hopes of diverting the police’s attention. Their plans failed, as the police quickly arrested members of Aum Shinrikyo and held them responsible for the sarin gas attack (Asahara was sentenced to death, but to date his execution was still kept in prison; in 2012, the last suspect on the run was arrested).

Mawaru Penguindrum, perhaps out of respect, did not directly address the 20th March 1995 attack in the anime as being committed by Aum Shinrikyo. Instead, it creates a fictional terrorist organization in place of it. The focus of the show was also not on how it affected lives at the time, but how it affected the lives of children of the involved parties. If Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995) was about how teenagers struggled to make sense of their existence in the 1990s, then Mawaru Penguindrum was about children living in the aftermath, or continuation, of the Lost Decade.

Battle Hymn of the Cultural Old

The Subway Sarin Incident caused a public panic and added to the society’s despair when the deteriorating economy was making people suffer. Even more shocking, many Aum Shinrikyo members were young graduates from elite universities. This prompted a wide discussion of what factors led to seemingly ‘better people’ in society to commit such acts. There was also discussion of how the education system, poor economy and dysfunctional family relationships all contributed to the occurrence of this event. Bit by bit, Mawaru Penguindrum tried to address and dissect these issues by providing us characters haunted by their own pasts.

Keiju Tabuki appeared to be just an ordinary senior high teacher, with the only thing distinct about him was that he was dating a famous actress. However, as the series went on, viewers learned that Tabuki was actually a victim of a perfectionist mother, who had an obsession with musical talents in people. She even divorced her first husband after reckoning he lacked talent, and married a promising composer, giving birth to Tabuki’s younger brother. The goal of Tabuki’s mother was to train the brothers into becoming pianists, preaching the idea to Tabuki that he lived for music and music only. After Tabuki deliberately injured his hands in hopes of earning his mother’s sympathy for once, she simply turned her back on him, since Tabuki could never play the piano again.

Here, it seems like the writers were playing with the stereotypes of Asian parents being Tiger Mom – in other words, perfectionists who think their children must excel in everything. It is commonly known that Japanese people value exam results a lot, which result in the popularity of tutoring centers and adding pressure to teenagers’ shoulders, since failing to be admitted to a top university would bring bad reputation to the family. Back in 1990s Japan, the situation was not that different. Everyone believed firmly that children were to follow orders of parents, that parents were doing this only for the benefit of the children in the future. However, they did not consider the emotional state of the children, thus putting an intense amount of pressure on the children who feared nothing more than failing their parents’ expectations. Like the representation in the anime, Tabuki was a bird trapped in its cage. His sense of self came solely from his mother’s perspective, and his rebellion of going against his mother’s will only proved his theory that his mother liked talents, not people. Tabuki never won against his mother, and when his mother abandoned him, he was doomed to utmost despair and a loss of self.

Formation of a child in a patriarchal society

Next, we have Yuri Tokikago and Masako Natsume, both victims of patriarchal society. Yuri’s father was a famed sculptor who only saw ‘beauty’ in his eyes. Curiously, though, his definition of beauty seemed to be those of masculine qualities only, with tall, erect sculptures that psychoanalysts liked to consider as representation of male sexual organ and symbol of power. Notably, his female sculptures were all broken in some way, as if suggesting that females could never be beautiful by all means. He constantly fed a young Yuri the idea that she was ugly, and that he would ‘fix’ her with his ‘love’. The implied sexual molestation further intensified the idea of him trying to manipulate Yuri’s thoughts, beliefs, and actions. If not for Momoka’s eventual intervention, Yuri would never be freed from her father’s absolute control. (Some fans also speculate that Yuri is actually a woman born with male genital, based on the vague monologue she has about her body, hence why she is told that she needs to be ‘fixed’.)

Masako also suffered from male suppression in her family, in her case by her grandfather, a traditional man whose obsession with absolute power made Masako’s father leave the family. Her grandfather despised ‘weak beings’, and aimed at training Mario, Masako’s younger brother with a weak body, to be a useful, strong-willed man to succeed his corporation. An interesting point was that her grandfather never seemed to consider Masako as a potential heir to his corporation, despite her talents and strong will. In his mind, Masako was a girl and hence not ‘suitable’ to take over his work. Even though Mario was weak and (stereotypically) more feminine than masculine, he was determined to make him a capable man by intensely training him with his traditional, masculine method. In his eyes, Masako was never a feasible choice. Even after the grandfather’s death (ironically, of overconfidence), Masako could not get rid of his shadow, for she had become a heartless utilitarian just like him.

Japan had long been a patriarchal society, granting men the power and rights while diminishing women’s status for centuries. In 1990s Japan, things had improved, but the idea of male dominance was still very prevalent. Here, Mawaru Penguindrum was not specifically criticizing 1990s Japan but the culture as a whole. The old, conservative males had dominated the political sphere for decades, and their failure to bring fresh changes bothered many Japanese. In society, the old-fashioned hierarchy also prohibited refreshing ideas from blossoming, because instead of wanting new ideas, they just wanted obedient followers. The traits that people worshiped – masculine traits such as competitiveness, independence, aggressiveness – were the reason why they could not break out of their own dilemma.

Deconstructing childhood

As the prosperity of 1980s became past tense, the adults were eager to equip their children with the best skills to survive. When that backfired, like the case of Tabuki, the children were deemed worthless, and were succumbed to the fate of being the ‘nobodies’ in society. Mawaru Penguindrum offered a highly dramatic, yet deeply haunting, solution to that: the ‘Child Broiler’.

The Child Broiler worked like a concentration camp, where children abandoned by parents/society gathered. It would crush the children and remodel them, making them transparent like a glass, hence they would become ordinary people on streets that you would not spare a glance at, them being fully alienated from society. This kind of existence symbolized the ‘ideal’ image of children that society expected them to be. Individuality and disobedience were not tolerated. Like a traditional East Asian culture, conformity was triumphant. The child was supposed to follow the lead of others and not breaking traditions.

Recall the Subway Sarin Incident, where those involved in orchestrating the attack were young elites with a supposedly bright future in big companies. They were, in a way, people who had followed the norm for a long time. Even though metaphorically they were not sent to the Child Broiler, it did not mean they were content with their lives. They felt hopeless about the future since they struggled with the meaning of existence when all they could do was to mimic others. It was with such a psyche that cults like Aum Shinrikyo sounded appealing, for they saw a possibility of changing their lives and changing the society that they were so discontent with. In the anime, the people who staged the 1995 attack also knew about the Child Broiler (as seen from Shouma’s later conversation with his father), and their way of fixing that brutal flaw of society was to transform it with the purity of fire, hence rebuilding a new world by destroying the old.

The Child Broiler ties back to the symbolism of the penguins that belonged nowhere. The only outcome for the nobodies was that they would be molded, by the education system and society, into becoming just another salaryman on streets. They had no purpose of life, for it had been taken away from them long time ago. They had nowhere to go, and even survival, the universal animalistic instinct, sounded like a dreadful idea. Were they really living when, like all the background characters of the show, they did not even possess a face?

The Frog on the Shore

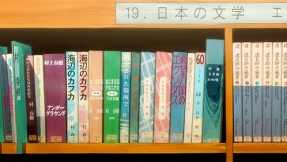

In episode 9, Himari was seen in the library, trying to find a book about a frog that saved Tokyo. In the background, many different books were displayed, but one that clearly stood out went with the name of Underground (1997), the author’s name being clearly stated as Haruki Murakami (b. 1949).

The story that Himari was looking for was actually a short story written by Murakami, after the Great Hanshin earthquake that killed more than 6000 people. (The earthquake took place on, not surprisingly, 1995.) The story was called ‘Super-Frog Saves Tokyo’, about a frog that fought an evil earthworm in order to save the people of Tokyo. The story was bizarre, but the point it tried to emphasize was the belief in the self that could make a difference. Any ordinary person, like the protagonist in this frog story, dared not to dream of saving the world by himself or herself, but in this story the frog convinced the protagonist that he could actually make a difference by stepping up. Given that episode 9 was about Himari’s past with Triple H, was this her fantasy of what her life would be like if she decided to stay in Triple H? It was hard to tell.

Underground was Murakami’s attempt to interview survivors of the Sarin Subway Attack. Apart from learning the perspectives of ordinary citizens involved in that shocking incident, he also managed to interview several members of Aum Shinrikyo and tried to get their point of view on the matter. (In the Japanese edition of the book, the interview with the cult members were published in a separate book, titled The Place that was Promised.) It was an important piece of journalistic work that criticized the public’s attitude of questioning what happened, instead of asking the proper question of why it had happened. In the anime, viewers knew that an event took place in 1995 that affected all the characters, but what exactly was the event about? Why did the people do that? What social factors attributed to the occurrence of such event? These are the questions that Mawaru Penguindrum asked, and one that we were left to ponder on.

The Scorpion Fire: The Real Penguindrum

The beginning and ending scenes of Mawaru Penguindrum featured two kids (implied to be reincarnation of Shouma and Kanba in the latter) discussing what ‘Kenji’ was trying to say. ‘Kenji’ here refers to Kenji Miyazawa (1896-1933), one of Japan’s most celebrated authors. His most famous piece of work, Night on the Galactic Railroad (1927), is a well-known story among Japanese, and one that has many references in Mawaru Penguindrum.

Night on the Galactic Railroad featured a poor, gentle boy Giovanni, who found himself on board of a train with his good friend, the kind and caring Campanella, after he took a rest on the hill. The train turned out to be one that traveled in the Galaxy. Throughout this journey, they encountered different passengers, who each had a story to tell. After learning their stories, such as some travelers whose ship had just crashed into an iceberg (implying the real life event of the Titanic in 1912), Giovanni and Campanella made a promise to never part from each other. However, Campanella soon disappeared from Giovanni’s eyesight when the train approached another station. Giovanni woke up, and in reality he heard the news that Campanella had sacrificed himself to save a drowning classmate. The train that rode through the Galaxy turned out to be one that transported people to their afterlife.

The character designs of the main protagonists of Mawaru Penguindrum, Shouma and Kanba, were based on Giovanni and Campanella. Like Giovanni, Shouma was a rather passive character who cared a lot for other people, and eventually he became a strong character who could stand for himself. Kanba was modeled on Campanella, who was born in a rich family and was raised as a caring person with a knight spirit of self-sacrifice. From the beginning, Shouma and Kanba contrasted each other much in personality, but like Giovanni and Campanella they showed great concern for each other, to the point that they knew they could not live without the others faring well too. Throughout the anime, even though Shouma and Kanda did not agree on everything, they still cared a lot for each other, with Kanba being Shouma’s ‘person of destiny’ and Shouma trying to save Kanba at the very end.

The story also had a parable of the Scorpion Fire, which symbolized the spirit of self-sacrificing for the better good. This paralleled the very idea of ‘penguindrum’, which was not to give up lives easily, but to be the light in times of darkness. The passion for life and the intrinsic motivation to heal others directly linked to the sharing of life, just like how the apple of destiny was shared among different characters in the anime. In the last episode, Ringo was originally consumed by the fire, but Shouma took over and let the fire consume his life instead. Such was the spirit of the Scorpion Fire that Miyazawa entailed.

Conclusion: beyond entertainment value…

Mawaru Penguindrum discusses many social problems in the story – child abuse, child negligence, family disharmony, discrimination, among many others. We easily think of events such as the Subway Sarin Incident as individual events that only happen once, but we fail to comprehend the roots of such events, which is why the social problems keep recurring without a pause. More importantly, like the Jacks in Chuck Palahniuk’s Fight Club (1996), these ‘terrorists’ as we know it are actually very normal-looking people standing walking past us every day. Mawaru Penguindrum tries to deliver the message that love is still the essential element in life that we should all share with each other, much like how Kanba, Shouma and Himari offered each other the apple of destiny.

Mawaru Penguindrum is known to be a difficult anime (personally speaking, I cannot say I understand it 100% either), with many more topics to cover than the ones listed here, but that doesn’t mean we should avoid trying to understand it in its given context. We cannot treat it as just an entertaining show and let it slip from our mind. It hopes to make us think, make us challenge the status quo, and see if we can figure out how it can be improved. We do not want something as ridiculous yet metaphorically realistic as the Child Broiler to exist in our society. It is a pity if we simply treat it as an entertainment show and do not think about the underlying message behind its complexity.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I just loved this anime- the visuals were total eye candy, the symbolism was just amazing, and Momoka and Sanetoshi are currently some of my favorite anime characters ever. Found this article really interesting. Plus, I find that if I go online and look up fan theories and such, it can be a ton of fun just because of how much is still foggy towards the end. Leaves a lot to the imagination, you know?

This is definitely not a moe-blob show. It is highly philosophical and very easy to not see the meaning in things, but if you do; this is one of the finest anime ever created! I can not stress enough how important it is to look for a significant meaning in trivial things. If you are the type of person who is open; the meaning will reveal itself to you. If you are the type of person who is not open; then you will be blind to the meaning.

I think the show is meant to show how confusing the world is and it is about trying to work out how it works hence at the beginning the person said sorry we can’t cure you with the science we have available today and how they go to the place where children go to die and the changing of destiny using a diary. It is all about mysteries and clues to unravelling them. It is also meant to do with relating to human emotion and how they think in unusual situations maybe.

Indeed it’s about the confusing world, but also an exploration of why the world (or in this context, 16 years after the chaotic 1995) has become like this, among other psychological problems.

The main twist of this masterpiece is about destiny, love and connection.

For me, the quick character developments weakened the characters, as not being able to pinpoint where the change took place made characters less convincing. I also think the first half was not even necessary, as it wasn’t all that relevant to the last half. I think elements within the last half should have been elaborated on. Also, distinguishing between reality and imagery was difficult, yes. Anyway, this is a very good article!

I don’t think the character developments are too quick. The first 8 episodes build up what they are like, and while it’s mainly for comedic relief it provides a good backdrop to the core of the story.

I’ve seen this anime, and it is one of my favorites. It just mess with your mind on so many levels. It was an emotional roller coaster for me, I laughed, I cried, and somewhat disturbed. I recommend this to any hardcore anime viewers, you have to see a good amount of anime to dive into this one.

I actually really enjoyed the series, albiet i watched the whole series just yesterday so bear with me. I found that you had to be quick to catch all the different devlopments. That being said, if you are like me, no trying to sound like a jackass, and followed the series easily, if not perfectly, that you would have enjoyed it to its fullest. Thats just me though. Frankly when i saw the end, i was baffled and for the 1st time in years, shed legit tears. Thanks!

I marathoned Penguindrum recently and I want to flip so many tables. I watched it because I enjoyed Utena enough to decrypt the movie so I was expecting the mess of symbols. I was also expecting a dark and complex surface plot as payoff for how toxicly animu much of the first half was. There is no surface plot. This is like an 8 hour long Adolescence Of Utena as if you never saw the series and it deters you from continuing with animu rather than surrealism. Just don’t.

This is a really awesome article. Congrats on getting it posted on the top banner thing.

Apparently there are some great confusion among people who’ve watched this. The show is a fest of symbolism. Mawaru = Round and Round. (Something like that) Penguindrum = Love. The show have it’s own supernatural elements. But miracles cannot be achieved without Penguindrum. The penguindrum was pass around the sibling through out the anime Here’s an interesting thing to look at. Ringo, actually means apple. Now think about the character Ringo… And try to understand what exactly is she.

I’m glad that you pointed out ‘Mawaru’ means ‘going round and round’, like a cycle of cycle. There are so many things to discuss for this show that it’s hard to refrain myself from writing too much. To me, letting Ringo (indeed, which means ‘apple’) to be the one who casts the spell at the very end in a stroke of genius.

I didn’t fully understand the symbolism. But after watching the ending, I ended up researching the analysis for it. I recommend researching it a bit. It’ll help you understand more about it and overall make you like the series more.

The anime almost reminded me of Tsubasa RC due to the confusing plot twists. hahah if my parents saw some of those “implied” episodes, well lets say they wouldnt approve

Thank you for this analyses. A lot of this show has to deal with symbolism. Much of the random imagery is meant to be symbolic and actually ties in very well to the main themes of this anime if you know where to look and what they are supposed to tie into. This show requires your full attention and should no be recommended to people who don’t enjoy though provoking anime that require a lot of thinking during, between, and after episodes.

I remember seeing that a while ago and I just never got round to watching it. I’ll add it to my list of things to watch (Although that list is currently over 100 dubbed anime strong, and seems to grow every week)

i saw this anime because i found it in the psychological anime category because i like steins gate but compared to steins gate this isnt good

It’s not really fair to compare the two since the genres and directorial styles are completely different. Steins;gate is science fiction while Penguindrum is almost surrealist fantasy.

I can’t compare since I haven’t watched Steins Gate (although it’s been on my to-watch list for a while). My friends who have watched both just like them both.

FYI: http://www.reddit.com/r/anime/comments/1wkxkw/exploring_mawaru_penguindrum_2011_from_a/

It is a common saying that stories are told through characters. Well, this anime really shows it.

The article described a realistic and precise view on the series, that’s why I enjoyed to read it.

Since the whole show was filled by all kinds of different comparisons, metaphors and many other symbols, it was really interesting to read an article that emphasizes some of the different symbols that were shown during the whole show.

For me, personally, the icon of the one big company that ownes everything in this standardized world was outstanding. But, although the whole anime talked to its viewers on a deep emotional and philosophical level, the ‘Fruit of Destiny’ in particular made me rethink some parts of my life. Considering the whole series from this point of view, it can help some people to assess their own lives.

But it was also a really good idea to include a quote from Kunihiki Ikuhara in your article. Although I haven’t heard anything about ‘Night on the Galactic Railroad’ yet, it was really good that you mentioned it here. When I put this into the context of Penguindrum, it’s just… Wow.

Where is it stated in the show that Shouma, Kanba and Masako were born on the same day as Ringo and the Train attacks? There is a scene where Shouma and Kanba are watching the incident on the news as it happened. They look to be about 7-10 years old. Did I miss something?

Ah, I can’t recall exactly which episode stated that, but all online sources I’ve come across stated they’re born on the same day (at least for Shouma and Kanba). Granted we know that they’re not related, but I also think they’re born on the same date based on deduction:

– Kanba was adopted, so naturally he could just be the older/younger brother of Shouma based on birth date, but he’s still considered a ‘twin’ of Shouma. The only logical reason I could think for this is that they’re born on the same date, hence why.

– Masako and Kanba are the real twins here, as we learn in the series.

– They watched the incident of their parents being arrested (where their home was being shown on TV), not when the incident itself happened.

Ah, I figured that they may have not been watching the incident rather they were watching their parent’s being arrested, just wasn’t sure. I would like to know where in the series it states or even insinuates that Shouma and Kanba were born on the same day. I’d trust the show over online sources explaining the show honestly. So pointing to directly to an episode would be great. Good article by the way, it clears up a lot of what the series is about, though there is definitely more to explore here as well as think about. I have a thousand questions as well as theories.

Totally understandable approach of verifying it. Unfortunately I really can’t recall which episode exactly, nor do I have the time to revisit the series yet. When I’m not as busy, I’ll definitely try to catch that and leave a comment here to let you know. My apology on that part.

No problem. I’ll be watching it again anyway as soon as time permits and will be looking out for that particular plot point.

By chance, I today was watching episode 23 again, and in the hospital scene Kanba did say to Shouma that ‘on the day that we were born…’ So, from there, it sounds pretty clear that they were indeed born on the same day

Another note that I’m not sure has been addressed anywhere, is why it is called the penguindrum. If Shouma, Masako, Kanba and Himari are represented by penguins then it makes since that the “drum” in penguindrum is the beating or drumming of the heart. Which is why the penguindrum is taken out of Kanba’a and Shouma’s chest. It’s pretty obvious now that I think about it and maybe that’s why it hasn’t been mentioned.

I didn’t mention that since I just want to focus on the historical, cultural and literal context. The mention of ‘penguin’ at the beginning serves as a backdrop to the historical/cultural context. I’ve seen people commenting that the ‘penguindrum’ is like the beating of the heart too, though I forgot where I first read that.

Thank you very much for this well-researched article! Mawaru Penguindrum has become one of my most favorite shows ever since rewatching it a few times. I discover something new out of the symbolism with each rewatch, but sometimes I don’t have the background knowledge to explain some of the other things, like Super Frog Saves Tokyo and Haruki Murakami. Ringo’s role as the apple was particularly poignant for me, personally.

OMG I only watched Night on the Galactic Railroad the other night so decided to reread your article.

Giovanni is a dark blue cat in the film, and Campanella is pinkish red.

Shouma has blue hair, Kanba has dark red hair. BRILLIANCE!!!!!!!!!!

Don’t mind me, I’m just really excited. It fits so well!

I have an older article focusing on the often-mentioned ‘punishment’ in the show. It covers how Japanese Society considers the criminal’s family members to be ‘guilty by association’ (think the Takakuras siblings’ fate). I hope it is appropriate to post the link here:

http://gorgeousshutin.tumblr.com/post/61861164763/punishment-penguindrum-style

This is a very thought provoking piece. I really enjoyed reading it. You should write more!

I have loved reading this as much as I love the anime. Its really enlightened me of the few things I was stuck at. I agree you should right more!! It has been a pleasure reading.

Last year I had a university lecture who studied on the underlying meaning of things that we should explore/question/intrigue and had a don’t take for granted, take it apart approach to our lectures. I am so sad to know he won’t be teaching anymore things like this really interests me. Like never been so engrossed in writing assignments haha and I am no master of writing.

I have loved reading this as much as I love the anime. Its really enlightened me of the few things I was stuck at. I agree you should right more!! It has been a pleasure reading. I read Night on the Galactic Railway years ago so this is just!

Last year I had a university lecture who studied on the underlying meaning of things that we should explore/question/intrigue and had a don’t take for granted, take it apart approach to our lectures. I am so sad to know he won’t be teaching anymore things like this really interests me. Like never been so engrossed in writing assignments haha and I am no master of writing.

I’ve been wanting to watch Penguindrum again since I finished it during the summer because there were so many intriguing things I want to pay attention to on the second time around. Thank you for this article. Now I have even more context to put the story in. There are so many things I take for granted in stories, I love it when other people help me pick extra gems out.

I’m in an MFA program (creative writing) and whenever people talk about their Cowboy Bebops or their Akiras I tell them they need to hit up Penguindrum. But when I try to explain what it’s about, I think I lose them a little.

Still, I’ma keep spreading the word.

Never knew that “Super Frog Saves Tokyo” was actually a direct reference. Without that knowledge, the episode in question seemed to be silliness masking the twist that came at the end of the episode. It’s rather nice to know that there is a bigger symbolic meaning behind it.

That’s some insight there fella. Mawaru Penguindrum is an anime I really enjoyed first time round. It was initially very hard to understand, some of it still puzzles me. Much of what you’ve written there is well thought out.

There is one point I’d argue though. That of the child broiler, which I thought was an indictment of the childcare system for those with social issues. It basically demonstrates those ‘unwanted’ were chewed up, spit out and worthless, as has been shown in the UK this week, by foster children staying with families well past the age they should be moving on. Although that system is there to help those kids, it in fact throws them away as soon as it can, with no help for their futures.

Also there’s a lot of Bhuddist references, and also Shinto references in there too.

Anyway, your essay was electrifying (Shaba-da-doo), thanks

Hi !

First, thank you for your writing.

Second, self-story.

I did watch Mawaru Penguidrum years ago when it was on going. I really enjoyed the series as it is hard to understand, but when you watch it, you know all the weird and funny stuff aren’t just weird, nor funny. There’s something else you cannot get, but you still catch a glimpse of something really, really interesting.

Years leater, as a hudge fan of Haruki Murakami, I’ve read Underground. I never knew about those events in 1995 (maybe because that’s the year I was born too) and the book really brought me to chills. I hate violence and I can’t handle terrorism, but most of all I hate it when people are conscious that something is wrong but they just watch being silent and useless.

Then I was on tumblr and found something about Underground that involved Mawaru. Then I was like. What?

Are you saying there is some link between this anime and the 95’s events in Japan?

I was like, blasted. It litteraly blowed my mind, and I was in tears. This was a incredible anime, but then It became more and more incredible because of that – and sad, of course. It’s a masterpiece.

I watch a lot of animes with philosophical or psychological reflexions but I would never have find any link between this one and those events. I don’t know why.

So I wanted to thank you, a lot.

I only joined the Artifice recently, but I saw this a year or two ago and I must say it is a fantastic article. I loved Penguindrum for it’s symbolism and undertones and this clearly depicts some of the more important points to these.

When I saw this pop up on the right while reading an article, I just had to comment saying I genuinely enjoyed reading this.

A brilliant, very informative and well written article. Sometimes you can enjoy a show or a book without its context, but I think in Mawaru Penguindrum’s case, knowing the context will add many new ways to understanding the show, and understanding Japanese culture and society. I send this article to anyone I’ve convinced to watch the show because I think it’s so important, and even if the person is not interested in knowing about the cultural context, it still helps in understanding certain elements that can be difficult to understand.

So thank you for writing this, I enjoyed reading it alot.

I watched Mawaru Penguindrum last year, I didn’t everything about it, but I can say that I could sense something. 🙂 That article rescued me, altough English isn’t my primary language (I’m Turkish) I understood your article. But still I wonder that what are the purposes of Double H, Shirase and Souya (Black Bunnies), Princess and the Prince of the Crystal World (actually the whole Crsytal World) and Momoka? Have you any guess for them? Thank you so much for great article (Sorry for my bad English by the way.).

Very insightful article, thanks!

always love to read smart, interesting, philosophical, deep, & thought-provoking articles like this, which discusses interesting (yet unfortunately/sadly quite underrated / not too ‘mainstream/popular/trending/hype’) anime.

Something that made my brain itch was that the use of penguins might be a pun on apple. In Chinese, it’s pronounce ‘pingguo’ and I heard an archaic Japanese pronunciation is ‘pingu’.

what a great review, thank you from 2021!

It would seem that there would be a significant influence or rather contra-influence from Japan in the 1980s.