Manga: How to Travel Between Dimensions

Manga narratives where the protagonist, usually a plucky and misfit teenager, travels to another dimension are fairly common. It’s common enough, in fact, that the author and a friend decided to carefully study this pattern. One of our team is developing an Original English Language (OEL) manga series that sees the protagonist travel to a fantastic dimension while he sleeps. The other is just generally interested in narrative, how a finite set of tropes and devices can produce a nearly infinite number of narratives.

We started out with a short list of seven or eight titles we chose mostly at random, and then, as our survey evolved, we cheated a little by choosing manga series that we felt would test or confirm some of the trends we thought we were seeing in those volumes we’d already read. In the end, we read chapters from eleven dimension-hopping manga (and one Korean manwha) to isolate their shared characteristics and the surprising divergences between them.

The idea was to read them the way Russian formalist critic Vladimir Propp read folktales. In his study The Morphology of the Folktale, Propp identified common characteristics of folktales, which he called “functions,” and showed how these same “functions” play a significant role in the development of the story as a whole—in other words, the parts not only reflect, but actually determine the shape of the whole. We wanted to do something similar: what common elements could we find between the manga? And what indications did the presence, or absence, or these common elements give about the larger narrative.

Portals, Spells, and Magic Items

We found that when characters traveled between dimensions, they did it in one of three ways. Some characters travel between dimensions with the aid of a portal– a geographically stable doorway between dimensions. For example, in Rumiko Takahashi’s InuYasha, for example, the “bone eater’s well” is a portal between contemporary Tokyo and the historical Japan where most of the adventures take place. In other manga, like Clamp’s Magic Knight Rayearth, it’s a spell that brings the girls to the alternate dimension. In this way, spells function like an unfixed portal: people can be picked up anywhere and deposited anywhere. Finally, in some narratives, like in Kentaro Miura’s series Berserk, there is a magic item that is necessary to making the transition between dimensions. In this instance, the ability to move between dimensions is bound, like in the case of the portal, to a physical item, but that item itself is mobile.

Eight out of twelve of the titles we read used spells to transport the protagonist. This meant that the magic, and the travel itself, was a one-off: once the protagonist was brought to the new dimension, the adventure and the protagonist stayed there for the length of the adventure. But when another method was used, there were striking implications. We found that in the two series where portals were used, that often created a circumstance where travel back and forth between dimensions was something the narrative allowed for. In InuYasha and also Q Hayshida’s Dorohedoro, the presence of a portal reveals an interest in both worlds, and in the case of Dorohedoro, a focus on the worlds on both sides of the portal. Dorohedoro was interesting in the sense that neither world was recognizable “our world,” which was also striking in our sample (Berserk is the only other title where this was the case).

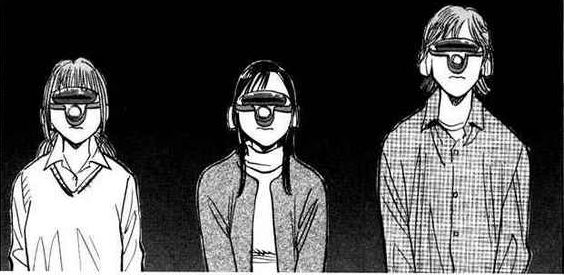

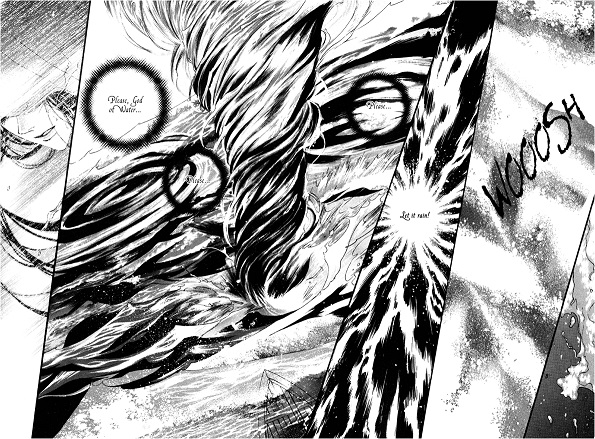

When travel was accomplished by the use of magic items, we found that the travel between dimensions was often delayed considerably. Often, the acquisition of the item itself was the result of some narrative quest on the part of the characters—that the characters were, in Propp’s terms, tested and a task was solved. It was the fact of being tested that proved the characters were ready to travel between dimensions. So in 20th Century Boys by Naoki Urasawa, Koizumi Kyoko is able to use the VR helmet to access the bonus level of FriendWorld only after she completes a number of tasks. And in Berserk, the Behilit is a magic item, small enough to hold in your hand that, when touched with blood, transports its user to the realm of the Godhand. But the acquisition of the behilit, and the ability to use it, is itself the result of a long narrative progression requiring the protagonist, Griffiths, to enter a state of despair. So in these instances, when a magical item was used to cross between dimensions, the acquisition and use of the magic items is itself the result of a discrete narrative sequence. The magic item is not “waiting to be found,” but is itself at a fixed location in the temporal progression of the manga.

Where Are We Going?

We were curious as readers about the kinds of places the characters would go. How could we characterize the alternate dimensions, and what role, if any, did the contrast between the dimension where the narrative started (in most cases, a world recognizable as our own) and where it ended up affect the way we read the themes of the narrative? We thought, briefly, of works like L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz, where the alternate dimension can be read as a comment on the original world, and wondered if we might find something similar in the manga we were looking at. In nine of the twelve manga we read, characters were sent to fantasy realms where there was no obvious connection to the original world, whether it’s the bleak landscape of Psyren by Toshiaki Iwashiro or the fantasy kingdom of Yun Mi-kyung’s Bride of the Water God. In the three series we read where the characters go someplace real—InuYasha, Red River by Chie Shinohara, also published as the Anatolia Story, and 20th Century Boys—we thought there might be greater thematic resonance in the locations chosen.

But we found that in the case of InuYasha and Red River, the choice of a historical location (Hattusa, the capitol of the Hittite Empire in 14th Centry BCE in Red River, and feudal Japan of the Sengoku period in InuYasha) seemed almost arbitrary to the story being told. No doubt the manga-ka had a fondness for that historical period, but as places, they could have been fantastic realms created for the manga just as easily. This isn’t meant as a critique, just a recognition the relationship between the make-up of the world often bears only the slightest connection to what the story is about, thematically. Just as in the case of Psyren and Bride of the Water God mentioned above, the contrast between the worlds or even the social structures of the new dimension should not be read as significant to the story’s broader concerns. As with most of the manga that featured travels to made-up worlds, the world itself is a sandbox and not a fundamental element of the story being told.

The exception to this rule is 20th Century Boys, which sends one its characters back to a specific day in the life of other characters in the narrative. 20th Century Boys is, broadly, about the use and misuse of a personal past as material to build the future. In the light of this theme, Koizumi Kyoko’s travels to the past, where she is not naturally invested, gives readers an opportunity to observe it more unsentimentally than the way the narrative’s dominant perspectives, Kenji and the Friend, see it.

But this kind of thematic work is not present in most of the book’s we read, leading us to conclude that a close relationship between the worlds traveled to and the world where the story originated is not a function of manga.

Gender and Genre

A third observation that arose from our reading was something of a surprise. We were thinking about cases when characters did and didn’t have guides to the fantastic realms they traveled to. We identified such characters as “helpers” in Propp’s terminology. He notes that helpers act in the following spheres of action: “The spatial transference of the hero,” “liquidation of misfortune or lack” and “the solution of difficult tasks,” all of which we saw in the manga we read. We found that if the protagonist was a man, he had a helper in Propp’s terminology, but if the protagonist was a woman, she was left to find her own way. At first, that struck one of us as contrary to expectations: men, who seem like bold adventurers, were given help along the way, whereas women, most often presented as helpless damsels, had additional challenges dropped on them by being forced to find their own way.

But ultimately, we tried to resolve this seeming contradiction by looking at the genre of the works and the sort of reactions the manga were looking to produce. Most of the manga we were looking at would be considered shonen, boys’ adventure comics, and if the adventure was exploring this new realm, why not give a guide to show the way to the biggest adventure. But in those where there was a female protagonist—like the Korean manwha Bride of the Water God or Red River/ Anatolia Story, the genre was more clearly shojo, girls’ romance stories. (The significant exception to this is in InuYasha, of course, where the human protagonist is Kagome Higurashi, a fifteen year old girl.) In these stories, the emotional life of the protagonist is a large part of the appeal of the manga for the readers, as they are able to trace and vicariously experience the struggles of the protagonist. If one of the goals of shojo manga is to create as emotionally powerful and engaging an experience as possible, it would be easier to achieve that goal if the protagonist were isolated and forced to find her own way. Or at least that’s what we thought.

In this case, what we were seeing was two linked functions: if the protagonist was male, he would be given a helper, in Propp’s terminology, but if the protagonist was female, there would be no such helper character. The presence or absence of that character would then play a significant role in the development of the narrative, so much so that it’s possible to see two different narrative patterns emerging.

What We Learned

In conclusion, Vladimir Propp’s work developing a system for classifying folktales helped some but not entirely to understand and predict the narrative development of dimension-hopping manga. So, in the case of how characters traveled, it is possible to isolate three separate methods and then from there to deduce certain narrative elements, which supports Propp’s broader thesis. The relationship between where the manga started and the new dimensions the characters traveled to was usually arbitrary. However, when it came to the intersection of gender and genre, we found a strong link between these two elements that allowed us to anticipate certain elements of the narrative.

A Survey Conducted by Partners Matthew Dube and Jennifer Iffrig.

Works Cited

Manga studied for this project:

1. Kentaro Miura, Berserk. Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Comics, 2003.

2. Tite Kubo, Bleach. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2011.

3. Yun Mi-kyung, Bride of the Water God. Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Comics, 2007.

4. Q Hayashida, Dorohedoro. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2010.

5. Kazuo Umezu, Drifting Classroom. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2006.

6. Rumiko Takahashi, InuYasha. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2009.

7. Clamp (Satsuki Igarashi, Nanase Ohkawa, Tsubaki Nekoi and Mokona), Magic Knight Rayearth. Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Comics, 2011.

8. Toshiaki Iwashiro, Psyren. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2011.

9. Chie Shinohara, Red River aka Anatolia Story. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2004.

10. Yuzuru Yushiro, Vision of Escaflowne. Los Angeles: Tokyopop, 2003.

11. Yoshihiro Togashi, Yu Yu Hakasho. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2006.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Naoki Urasawa is king.

Great narrative analysis and literary criticism. I need to read more manga.

I’m very intrigued and will start to read some of these mangas.

Wow, excellent analysis! It’s especially interesting what you pointed out about gender and the lack of a helper archetype in most of the female-led narratives.

Dorohedoro was my first experience with Manga, and I have to say I loved every page of it! This was a great study, kudos to both of you for doing it.

Berserk is the best dark fantasy title in manga form; period.

I tend to be a lot more into the more recent anime/manga, but InuYasha is an excellent example of an older work with a really strong storyline and the potential for a very cute romance.

Vladimir Propp must have spend a considerable amount of time analyzing fairy tales and testing his framework for tale constructions!

Dorohedoro was a pretty good manga

I only recently started reading manga. I admit, it took a while for me to get used to the whole “read from the right” thing but once I figured it out it was pretty amazing to follow.

Berserk is one of the most violent manga I have ever seen.

This was really a fascinating study.

I have a great passion for folkloristics!

InuYasha is a series that I adore.

Why did I ever stop following InuYasha? For a long time, I was reading each volume as it came out. Maybe I got lazy, or maybe I forgot to watch for it.

Propp’s foundational work on the structure of fairy tales is impressive, and it’s a wonder that his work didn’t find its way into English literary circles sooner than it did.

I haven’t read much of this kind of thing in manga so maybe I’m overly impressed but I think it’s brilliant.

Morphology of the Folktale is an incredibly academic analysis of fairy tales.

I like the study-style of this article Another manga that featured dimension travel, (pulled off in a half-ass way in my opinion) was Naruto. And lately, it seems to be going down that path too. Happened in the end of the manga, The Last, and Boruto.

That was very nicely put.

Wow, excellent analysis! It’s especially interesting what you pointed out about gender and the lack of a helper archetype in most of the female-led narratives.

The “isekai” trope is common in Japan because it allows the target audience (usually young boys) to really connect with a more fantastical world, through the character lens of someone just like them. When it is done well, it is one of the most exhilarating genres out there.

Isekai is an interesting genre that appeals to many different audiences, which explains why there are so many in circulation. My personal favorite is Konosuba.

Great Read.

Very thorough article.

It looks like you didn’t understand how the “Works Cited” section worked here.