Otaku as Artist: Hideaki Anno and Neon Genesis Evangelion

With comparatively few exceptions, the sensibilities of anime as a medium seem to grate against the standards by which most American film critics evaluate foreign works of art, and recent attempts in the West to reassess works of media through more progressive lenses have only widened this divide between Otaku and critic. While the revered Miyazaki retains untarnished respectability among enthusiasts and casual viewers alike, there is one equally influential director who may find his greatest work out of place among us, if it were made today. On the surface, he is an artist whose sensibilities run counter to those of Miyazaki, Yuasa, and Kon, all of whom reject the conventions of their own medium in favor of styles that, for various reasons, coincide more directly with the tastes of the West. Meanwhile, this man began his career by embracing his identity as an ardent anime fan, and later formed the thematic arc of his premier work around his evolving relationship with the Otaku lifestyle. Yet perhaps it is because he explored this subject with such untainted love at first and such unflinching honesty as he progressed, that his importance as a creator shines the more brightly today. This article will examine and celebrate an indispensable artist’s background as an unabashed fan of a once niche but still largely disrespected medium, his subsequent disillusionment with its more indulgent aspects, and his ultimate legacy as both a great anime director and as one of the world’s most fascinating filmmakers. Meet Hideaki Anno, creator of the legendary series Neon Genesis Evangelion, and co-founder of the equally legendary Studio Gainax.

![]()

The studio was noted for its reckless ambition: stretches of beautiful animation that awed audiences with the depth of care invested in them, contrasted with visibly rushed attempts to conceal insufficiencies in budget and resources; a boldness with which their series embraced both visual and narrative experimentation, sometimes undercut by an off-putting directness concerning the thematic subtext; the women. Anno himself is as guilty as his collaborators. His spectacular moments belie an intimidating devotion to his craft, his fan-service an equally compelling shamelessness, and his use of psychological tropes, sheer courage. Neon Genesis was groundbreaking partly due to how astonishing it was to see an extravagant entry in the mecha genre strip itself down to a purer meditation on themes of identity, isolation, and individuation. Of course, this shift in tone does not come from the ether. The more openly beloved first half of the series establishes itself as a nuanced take on the coming-of-age tale, and there is no theme more pertinent to growing up than that of intimacy. In his most well regarded work, Anno takes an unflinching look at the nature of intimacy, and by grounding a painfully human theme in a classic anime premise, he pays his respects to a cherished tradition within the genres.

It is no secret, after all, that the best genre stories are broad metaphors for something much closer to home. Director Joe Cornish, whose debut film Attack the Block shines as one of the most successful attempts of blockbuster cinema to touch on the concerns of urban youth, acknowledged this pattern himself when he cited Ishiro Honda’s Godzilla (the atomic bomb), John Carpenter’s The Thing(Aids), and George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (racism) as precedents to his approach. Indeed, genre thrives precisely because it addresses resonant themes through terms as vibrant and colorful as cowboys, gangsters, superheroes, hobbits, wizards, Kaiju, and, yes, giant robots. Neon Genesis Evangelion is no exception. It may, in fact, be one of most uncompromising examples to achieve mainstream recognition.

It is uncompromising, most notably, in its deptiction of loneliness, which has always been a powerful theme in great art, but has never been depicted with such an uncomfortable lack of distance. To elaborate, viewers stand apart from Travis Bickle’s misanthropy, even as they empathize with his inner pain. Evangelion, on the other hand, is a story told from the depths of depression itself, and the mental state of its author ends up warping not just the psyches of the cast, but the storytelling as well. This lends the series its much lauded emotional intensity, while also drawing ire to its final episodes, wherein the protagonist delves deeper into self-analysis as the show’s earlier spectacle is eschewed entirely. What carries our interest regardless is Anno’s power as a visual storyteller: stark compositions rhythmically woven together by tight, efficient editing, and an ability to use minimalistic imagery to hint at events much more ominous than the imagery itself. It is a strength that Anno slowly developed through the early stage of his career, until he was capable of telling unconventional stories with an almost classical sense of craftsmanship.

His skill as a craftsman must be stressed. The cinematography, sound design, and editing in the first two thirds of Neon Genesis do as much to sell the world of Tokyo-3 as the actual world-building: the slick Willis-meets-Kubrick framing, the provocative sound mix built around the humming, snapping, and firing off of highly advanced machinery, and a no-nonsense narrative style that perfectly balances character development with the build-up to each climactic battle. This is the pace of classic science fiction. That there are many moments of exuberance interspersed throughout these episodes attests to Anno’s ability to keep himself disciplined even as he exudes such enviable style.

When resources then bled themselves dry, he attempted to salvage his masterpiece with the power of craft, a power which held the show together even as the sudden shift in form shattered all previous notions of what exactly Evangelion was supposed to be. Anno’s attempt to work around financial constraints by delving deeper into experimentation is admirable. To some, it may call to mind the arc of Orson Welles’s European output, where the master compensated for a lack of studio support by voicing multiple roles, employing clever misdirection to hide a dearth of available extras, and artfully assembling the scattered pieces into a body that cohered thematically, if not geographically. Anno’s efforts were even more impressive, because the stakes were higher. His series was not an obscure indie production screened for an audience of connoisseurs, but one of the most critically successful works of anime in history. That Anno suffered through deeply troublesome financial and scheduling mishaps throughout Evangelion’s production, and still managed to conclude his opus on a compelling, if imperfect note proves that he has the essential quality of the artist. He has the ability to preside over accidents, and still deliver an unforgettable experience.

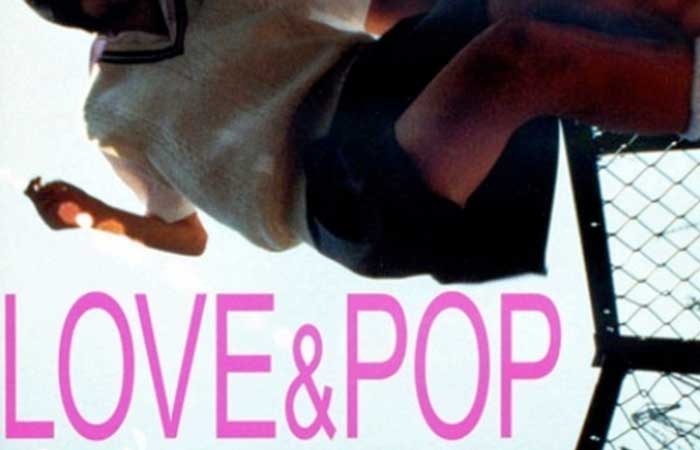

There is, however, the other side of Anno we must contend with, a side that exemplifies the more indulgent habits of anime as a medium, and of its enthusiasts in the public conception. We must remember that Anno effectively began his career by slaving away at a technically impressive tribute to Otaku culture, the beautifully animated promo short Daicon IV, which frames its eclectic array of pop-cultural references around a now iconic image of a playboy bunny suit. It is in this period of his career that Anno steadily formed the stylistic inclinations that would serve him well as his ambitions grew in scope. While Nausica of the Valley of Wind showcased his gift for creating behemoths with an imposing presence, classic mecha shows like Macross and Gunbuster taught him how to pit giant, weighty military robots against each other in vigorously animated set-pieces. Then, following the successful but mentally taxing production of Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water and his subsequent failure to begin production on the sequel to Royal Space Force, Anno transcended his resulting depression by taking an incredible artistic leap. Yet his older habits never really left him after The End of Evangelion. He was still the man who would adapt Cutie Honey into a boldly bizarre tokusatsu film, a project whose lack of self-consciousness surpasses that of many quintessential Super Sentai properties. He was still the man who would intersperse his brilliantly experimental Love and Pop, a thoughtful indie gem about arrested development, the sentimental roots of materialism, and the emotional pains of growing up, with invasive camera angles either looking up girls’ skirts, or down from them. In this film, Anno’s style is characterized by an anarchic sense of freedom from cinematic convention, a love of stylish ebullience for its own sake, and a playful irreverence for personal boundaries. His more whimsical moments within Evangelion evoke Astaire musicals, while his Love and Pop evokes the frenetic energy of Wong Kar Wai’s ChungKing Express.

Then there is the other half of Anno’s style, the half that kept the premise of Neon Genesis Evangelion grounded in painstaking verisimilitude, imbued deeply entrenched archetypes with darker emotional depths, and most notably, rejected the monomyth in favor of introspection. At the culmination of his opus, he then took everything he once loved about Otaku culture, and examined it in the controversial theatrical feature, The End of Evangelion. Here the uglier aspects of anime fandom in particular and of stunted maturity at large – the misanthropy, the wish-fulfillment, and the tendency to deny the harsher realities of the world – spills over from the subtext right onto the text itself, and Anno’s artistry reaches terrifying new heights. The film displays a mastery over craft that ranks alongside Angelopoulos, Mizoguchi, and Tarkovsky in its ability to gracefully hint at deeper emotional turmoil. Moreover, the level of skill demonstrated in the film’s finer sequences is so breathtaking that it almost sheds an unflattering light on the actual substance. The breadth of command that Angelopoulos used to explore themes of poverty and war, that Mizoguchi used to fight for womens’ rights in Japan, and that Tarkovsky used to contemplate the loneliness of life in exile, are here used to plumb the depths of adolescent angst. Except this specific story also has a specific message for both the anime industry and its enthusiasts, and it is this message that makes the series especially resonant in today’s world.

Shinji Ikari’s story has much in common with the millennial narrative at large, because Evangelion essentially charts his struggle within a world that threatens to discard him for not serving it in a specific way. In order to reclaim his sense of self, he must first overcome a deeper psychological dilemma. He must stop using fantasy to escape the real world, and instead use his imagination proactively, to create a better reality for himself and for others. In a time where nothing is as it “should” be, where higher education does not guarantee a stable living, where “following your dreams” may lead one through an inordinate amount of hardship, and where incredible pressure is heaped on the young to succeed by standards set by preceding generations, millennials may find this aspect of Shinji’s story painfully relatable.

Anno achieved something great when he gave vent to this very human understanding, which is both inseparable from his own history as an Otaku, and yet one that he could only have reached after much self- questioning. His older enthusiasm for nerd culture never left him. His most recent work, the newest installment in the Godzilla franchise, proves to be a delightfully idiosyncratic yet reined in take on a classic Japanese property. However, his older, much more revered masterpiece marked the point where he grounded his trademark enthusiasm for nerd culture in much more thought than audiences were then accustomed to. It is for this reason that Anno may claim his title as both the definitive Otaku, and something much more than the label suggests. It is for this reason that he still sits on his throne as the definitive Otaku artist.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

WOW! A really great article. I learned a lot.

Evangelion has always been something he’s poured his heart and soul into like no one else has with anything. He really poured all of himself into it and made it so personal to him because he just got the freedom to make whatever he wanted at that point in his life. It’s something impossibly unique to who he is and what he could put into it and I don’t think anything could have been created with how much of himself he put in than how he did it with nge.

Agreed. All creators should envy the sheer depth of intimacy of the original series.

Anno continues to be the best argument for death of the author as a form of literary analysis.

It’s refreshing to see someone actually analyzing Anno’s style, instead of just regurgitating the same biographical information and personal-life rumors that typically come up when discussing Anno’s influence on NGE.

This man is doing God’s work.

I’d heard a lot about Hideaki Anno before. This guy sounds like a real eccentric. There are a number of Japanese animation directors that I would hope would do some American work. I’m not sure that I’d want Anno to work on any American cartoons. He’d probably make it weird,dark,and angsty.

Now that I think about it, Anno’s been completely incapable of properly completing a TV anime.

I’ve wanted to watch Evangelion but I have no idea where to start. Anyone have suggestions? Is it even worth watching or is it overhyped like Sword Art Online?

Evangelion isn’t overhyped at all. SAO absolutely was, but Eva is so much better you can’t even compare them. Everything everyone says about it being a deconstruction, having great characters, that’s all true, except it may end up being MORE “anime-like” and entertaining than you anticipated.

Watching Eva is simple. Watch the 26-episode series, with the directors cuts’ of some of the final episodes if you can. Then watch the movie “End of Evangelion”, then watch the three Rebuild films that have been released. That’s it.

My only advice to you if you watch Eva is, try to keep an open mind and form your own opinions about the show and especially the Rebuild movies. Don’t just read one person’s interpretation and take that as the facts.

Start with the old TV series. Personally, I would say, watch all the 26 episodes. Then the movies, Death and Rebirth, and The End of Evangelion.

Then read the manga.

Then watch the new movies, 1.0 You Are (Not) Alone, 2.0 You Can (Not) Advance, and 3.0 You Can (Not) Redo.

That is how I watched it as it was slowly being released, hanging on each episode as a fan. Evangelion is definitely worth watching. I would say it is the “best” series, or most entertaining, but it is very thought-provoking. It’s a bucket-list type of series. So many other anime and manga make references to Evangelion. Like Dragon Quest, there is a certain amount of pervasiveness in Japanese Pop culture that it is worthwhile to familiarize yourself with it so that you’re not totally out of the loop.

Personally, I think Evangelion is interesting enough that it is accessible to a varied demographic. Sword Art Online is not a show I could recommend to any random person, it’s more of a niche taste to a niche age group.

Leon, I agree with both ad and Dillon about the order of viewing, but i would like to clarify Ad’s point about having an open mind while watching the original television show.

First, don’t worry about Neon Genesis being over-hyped like Sword Art Online. It isn’t. To put it mildly, the two shows are polar opposites in terms of both artistry and fundamental mindset. While SAO both exemplifies and panders to some of the baser inclinations of anime culture, Neon Genesis still crests the very highest tier of artistry both within that culture, and possibly within the larger sphere of art cinema as well. While Sword Art was designed purely as an escapist experience (and yet due to muddled decisions in its execution, falls relatively flat as that for more jaded viewers) Neon Genesis stands as a fascinating work of art that also happens to be a masterclass in, well, all flavors of entertaining.

It’s masterfully paced, for one thing. The characters are immediately relatable yet richly textured and multi-faceted. The series as a whole is structured and directed like “the best monster-of-the-week show ever” (in the words of an anituber of old), but juggles an entire breadth of emotion over the course of its run, from lighthearted rom-com to thrilling procedural, from atmospheric art-house straight down to avante-garde psychological horror. I think Geoff Thew, a great anituber, made an excellent point about tonal shift being the most interesting thing about SAO. Well, imagine that, except so effective it’s like the show is dancing on air. At times stylishly, at times gracefully, always with sublime precision.

However, (this is the open mind part) I should warn you that NGE is also an incredible work of art, and like all incredible works of art, it is uncompromising.

From the beginning of the show, Anno makes it very clear what kind of story he wants to tell, and the level of performance with which he wants to tell it. He never once strays from these intentions, nor does he sacrifice them for baser commercialistic purposes (i guess you could say his team made the designs too iconic and cool, or something. ) Every moment, whether it’s a briskly paced badass mecha fight or a nuanced, slow-burn exchange of looks, is drenched in emotion and dense with meaning.

And the show doesn’t always give itself to you, either. Just look at the characters, and how audiences have responded to them since the show premiered decades ago. Shinji has in large part become a meme because doesn’t fit into the classical hero mold, though decisions to withhold themes of actualization like this (in this specific way) is one of the biggest reasons the show has endured for so long. That’s the difference between an easily digestible, well-liked memory and an iconic long-standing work. The first serves its narrowly defined purpose, and is gone. The second thrives on friction to go far.

But i think i’ve gone on long enough. Lol this was supposed to be a short comment, but the didact in my took hold.

Is it overhyped? To be honest, it has been overhyped a bit, now don’t get me wrong its a good show, but it has been hyped to such monolithic heights that now show could ever live up to. You also need to understand the context of the series, it was one of the first series that aired in the US that tried to deconstruct mecha shows AND deal with philosophical and emotional matters of the cast, and since it did it very well, it basically blew the minds of everyone who watched it at the time, and its really hard for people to separate that from the show itself. Again, its a good show, but keep your expectation in check.

But, whether you will enjoy the show is entirely dependent on what you like in anime and whether you can look past the bit outdated animation and pacing, and how do you feel about a negative and emotionally damaged protagonist. (I mean, Shinji can be a whiny bastard sometimes, but in the context of the show it works, but it does get a bit tiring sometimes).

I’m looking forward to his future projects and I mean the projects “after” the Evangelion films. Because I still have a gut feeling the fourth film will not be the last.

He is finally embracing his destiny as the next Miyazaki. Took long enough. Stop fighting it Anno.

No more live action.

He conjured this entire series out of his mind. If it weren’t for him we wouldn’t even be here right now talking about this.

I’d rather have 4.0 later, when Anno has rebuilt some soul to chip off, than a soulless 4.0 now.

I was glad Anno got to do Godzilla and put the last Rebuild on hold. For one, I felt happy for him. Being one of my idols, it was great to hear he got an offer to direct something bigger than Eva. I would imagine it would be like someone coming to me asking to direct the newest Star Wars film and put my lesser known works on hold.

What I loved about Anno’s work is it’s very postmodern taste. If you know what I mean.

He’s created something that has reached out to so many people…

I never really took the time to think about how stressful working on a project like Evangelion might be. I heard he went through hell.

I swear, Anno, I will choke you out if :Final ends with something like, say, Shinji and Kaworu getting it on.

Wouldn’t it kick major ass if he did it so that Unit-01 fights Unit-13, though? (What ever happened to it, anyways?)

I love Anno so much, and I love Evangelion!

I’ve never seen all of the original Eva, but Anno’s an interesting person and I absolutely loved Insufficient Direction!

I love everything about this man. He really needs to be more formally recognized, not to say that he isn’t a god in animation as it is.

I know the guy probably has franchise fatigue or writers block but god damn it can he finish Rebuild. I’ll be dead by the time he puts out 4.

If we interpret anime as art, will the prejudice of non-anime watchers begin to slip away? But then, if they begin to watch with us, will anime become too “mainstream?” and less special? Do we need the haters to remind us of why we keep watching?

He conjured this entire series out of his mind. If it weren’t for him we wouldn’t even be here right now talking about this.

cool!

I believe the audience can know a lot about Hideaki Anno through Evangelion. The existential crises, depression, loneliness, the struggles of human relationships all reflect the disturbed mind of Anno. I also think he succeeded in making a lot of people understand his views about human existence and relationships.