Queer Representation in Anime

I was five years-old when I first entered the closet. I kissed a girl at recess and was scolded by my teacher, “girls shouldn’t kiss other girls on the lips.” (Note: If you read my name and are confused, this was 15 years pre-transition from female to male.) In contrast, the kisses I planted on boys at recess were acceptable. Surely this experience is not unusual for American children, particularly those having grown up in small towns before the liberation of queer youth in the 2010s. My bisexuality was not necessarily revolutionary, but exhibits of same gender attraction were definitely unwelcome. Yet there was another incident in my kindergarten career that kept me in the closet, one separate but unexpectedly linked to the topic of my sexuality.

It was the day five year-old me was brought in for a parent/teacher conference regarding my interest in anime. I had drawn a picture of anime heroine Sailor Moon fighting villains, and the question was whether this was acceptable material for a child to be emulating. Sailor Moon is a popular Japanese animation of the 1990s that teaches lessons of acceptance, feminism, and friendship. American cartoons, like Looney Toons, were apparently acceptable to the adults in my life, despite the material of such being arguably raunchier. This was around the time little me brought anime into the closet along with my sexuality where I would not proudly reemerge until my adult years.

Much like with queer individuals (Note: In this analysis, I will refer to “queer” as an umbrella term for non-heterosexual identities), queer representations in anime have been and are currently still kept in the closet. The community is often overtly sexualized in anime, but more often than not, we are made invisible. The biggest contributing factor is censorship by Japanese studios and American networks. Censorship in this case can be cutting funding for an anime after backlash, English dubbing that fails to translate same gender attraction, editing animation cells to hide visuals of queer romance, and more. Neither Japan or the United States have official codes against representations of same gender romance in anime, but the actions of studios and networks reflect a generalization of profanity as seen with Sailor Moon (1991) and Neon Genesis Evangelion (1995).

Such censorship is harmful to fans of anime, and it reflects a societal ideology situating same gender romance as profane. Queer anime is kept in the closet and the closet contributes to the marginalization of queer individuals. Anime rarely represents queer individuals well, and though newer examples like Yuri!!! On Ice (2016) come close, they still fall into the same closet kept only slightly cracked by studios and networks. There have been a few positive improvements, like the somewhat rare No.6 (2011), but a medium with over 400 animation studios has an unacceptable trend of negative queer representation. I believe drawing awareness to this underrepresentation is one of the steps in bringing positivity to a marginalized community. In order to understand how and why this censorship occurs, one must first take a step into Japan’s history with anime and sexuality.

A Brief History of Anime

Anime is characterized by hand or computer drawn animation originating and produced in Japan. Popular anime in Japan are distributed to the American market, either translated with English subtitles or dubbed with English speaking voice actors. Anime scholar Robin E. Brenner suggests the origins of anime reach as far back as kabuki theater in terms of styles of storytelling, but when Japan became influenced by Western comic strips and cartoon reels in the early 20th century, the country began to develop its own modern visual media: manga, and then anime. Manga is Japanese style comics, which anime is commonly adapted from. Author of Anime’s Performativity: Diversity through Conventionality in a Global Media-Form, Stevie Suan identifies manga through “practices of panel layouts, common conventionalized facial/bodily expressions, as well as character design styles and narrative content” and for anime, the addition of “voice acting styles, background, world-setting and sound designs,” and the more nuanced “techniques of animation, styles of movement, narrative structure and pacing.” (Suan, 64) The formulaic narrative and visuals of anime lends itself to fast production and high demand. An important key in the creation and distribution of anime is the categorization through genre. While there are categories of anime similar to those in Western media such as drama, comedy, horror, etc, two different major genres exist in the anime industry: shōnen and shōjo, literally translating to young boy and young girl, respectively. The gendering of anime is part of how the tropes and messages within the formula work.

Shōnen has dominated the anime industry since anime’s emergence as a major marketable visual medium. Science fiction was one of the initial popular subsets of shōnen with roots in the classic, Astro Boy (1952). In the 1980s, the giant robot subgenre of shōnen, otherwise known as mecha, rose to popularity. Mecha was influenced by the emergence of new technology like computers, VHS, and cellphones into everyday life, and the paranoia that came with it. (Brenner, 66) Mobile Suit Gundam (1979) and Macross (1982) were major mecha series that gained notoriety in Japan and the United States. With influence from George Lucas’ films into the 1990s, space opera shōnen like Outlaw Star (1996) and Cowboy Bebop (1997) became popular series’. At this time, the distribution of anime to American television networks targeted to a young male audience had begun. Major shōnen series’ Dragon Ball Z (1989), Yugioh (1996), and Naruto (1999) were huge successes in the United States likely because of their similarities to American comic book heroes, but through a new style that mixed fantasy and martial arts. Pet companion shōnen like Pokemon (1997) and Digimon (1999) also became huge hits based on Tamagotchi toys, and though these series’ emphasized ensemble casts, they mostly focused on the development of the male protagonists through fantastical fighting tropes. Unlike American cartoons which have largely been dominated by Disney films and Warner Brothers, anime geared at children maintains a layer of adult content as most shōnen deal with topics of violence, family abandonment, and death. On the other end of the spectrum, shōjo , the genre geared at young girls, tends to work through different topics.

An argument against classic Disney cartoons has been the emphasis on princess role models for young girls, while male role models are of a wider selection. This argument can be applied to anime and the gendering of genres, as well. Shōjo tends to deal with topics of romance, friendship and femininity through the lens of female characters. Many early shōjo stories took place in school settings, relying on realism with formalist techniques derived from manga. As a pushback against shōnen, the magical girl subgenre became the most popular form of shōjou with classics like Sailor Moon (1991), Revolutionary Girl Utena (1997), and Cardcaptor Sakura (1998). For this type of anime, young female protagonists are imbued with magical powers to fight (typically male) villains, often with the help of their female friends. Tropes of this genre include princess-like outfits, sparkle effects, soft pink hues, and flowers either in the narrative or as effects. While this genre also deals with fighting like in shōnen, shōjo fights are far less bloody, and often resemble dance instead of martial arts. Probably the biggest difference between shōnen and shōjo, apart from the obvious “girl power,” is the heavy emphasis on romance. Nearly every episode of Sailor Moon, Revolutionary Girl Utena, and Cardcaptor Sakura has a romantic subplot regarding the main character or one of her friends. Yet an interesting aspect of the magical girl genre and the above mentioned anime is the inclusion of queer themes. While Utena‘s homosexuality is veiled under a layer of abuse, nonconsensual sex, and slavery, it does include strong themes of both female/female attraction and male/male attraction, all ending by tragic means. In Cardcaptor Sakura, both boy and girl characters state their attraction to same gender individuals. CLAMP, the publisher of the Cardcaptor Sakura manga, has been widely known for consistent representation of queer themes. Another subcategory of shōjo known as moe, is a genre encompassing young relationships and cuteness, mostly targeted at heterosexual male fans. Moe has been criticized for its fetishization of young women and girls, with Lucky Star (2007) as an example. Many have found queer representation in these depictions, albeit inauthentic and fantastical, as the characters often share same gender kisses and affection. However, queer representation in anime cannot be fully understood or deconstructed without a deeper analysis of Japan’s history with sexuality.

A Brief History of Japan’s Sexuality

Japan as country exhibits a strong assertion of nationalism and preservation of culture, meaning the society has also adopted a sense of cultural cohesion which, unlike in Western societies, does not outwardly condone individuality. Thus, in Japan, one does not always assert feelings or behaviors that would draw attention to difference. Interestingly enough, this avoidance of emotional expression applies to how the Japanese say, “I love you” or more so, how they don’t. It is common for romantic couples to say “suki da” which literally means, “I like you.” The phrase, “aishiteru” means “I love you” but is not often used. The choice to use a phrase without as much emotional depth could be due to Japanese not wishing to draw attention to personal feelings, as such would accent individuality. Applying to both heterosexual and queer relationships, stating one’s love is not common in Japanese society, thus the Western notions of romance do not always apply in Japanese culture.

Before World War II, Japan was known as a closed culture with a firm emphasis on the traditional family structure to promote nationalism and growth of the population. Masami Tamagawa discusses the root of this concept in Coming Out to Parents in Japan: A Sociocultural Analysis of Lived Experiences:

Rooted in Confucianism, the traditional Japanese family system was defined as a basic unit of Japanese society in the Meiji Constitution (1890), enforcing various familial duties on its members based on gender and seniority. Although the old system was abolished in postwar Japan, Japan’s family tradition persists, due mainly to the national family registry called ‘koseki.’ Remaining nearly unchanged, Japan’s family registry continues to oblige all Japanese households to register their family members based on the traditional family system. Each family registry is hierarchically organized, thus subjugating women and excluding LGBT individuals. (Tamagawa, 5)

Despite the necessity for a traditional family system, Japan’s recorded history of homosexuality dates back as far as the 11th century. Tamagawa describes historical evidence of male/male romance in kabuki theater, as performers were always male and resided in close quarters with one another. It was also common for older men to be involved in romantic relationships with younger men and boys around this time. Homosexuality continued with Emperors and in religious institutions, then became very popular among samurai warriors who were often traveling without women. Hishikawa Moronobu depicted same gender love between samurai in 1680s era nanshoku erotic art, one of many artists to do so during the Edo period. However, Tessa Morris-Suzuki, author of The Invention and Reinvention of “Japanese Culture” says Japan’s historical stress on “national culture,” including the demoralization of homosexuality, was tightened in the 19th century with influence from Europe. This change can be attributed to the enactment of the Meiji Constitution.

The Meiji Constitution and the French influenced Keikan code of 1881 condemned homosexuality as a deviant act and demoralized men appropriating femininity. Gregory Pflugfelder, a scholar of gay male romance in Japan, suggests how this major change in Japanese morals was derived from the fear that men in homosexual relationships would become more like women, thus challenging reproduction. Sadly, not as much is known about queerness between women in early Japan, but it has been suggested that as long as women bore children, they were allowed to engage in same gender romance. The closeting of queer individuals in Japan persists today, over half a century after Japan was forced to open its culture post-war. A 2007 study done by REACH Online found that among gay and bisexual men in Japan, about 8% of the participants had come out to both parents, 6% to mothers, and less than 1% to fathers. The article also discusses how “pink films” or lesbian pornography stigmatizes female/female love as a fetish and does not make it easy for lesbians to come out in Japan. Some queer individuals in Tamagawa’s research said they felt more included in LGBT subcultures of manga and anime; however, most of those depictions of queer romance were only in sexualized, pornographic-esque publications known as yaoi and yuri.

Similar to the gendered categories of anime (shōnen and shōjo), yaoi and yuri have specific marketable tropes. Tamagawa describes yaoi or “Boys Love” manga and anime as stories of “romantic relationships between effeminate young boys” which grew in popularity starting in the 1970s. These publications are popular among fujoshi, or young women, mostly heterosexual, who enjoy reading male/male romance. Common features of yaoi are men who look and sound like women, known as bishōnen, who are often coupled with larger, more masculine men. This type of coupling asserts the heteronormativity of “traditional” relationships in which one must be feminine and one must be masculine. With this trope, many yaoi also depict abuse and negative power dynamics which further demoralize male/male romance for a heterosexual audience. Yuri or “Girls Love” has been less popular, but center around female/female relationships. These publications can fall into heteronormative tropes of masculine and feminine couplings, but more commonly, yuri stories are populated with highly sexualized images of young women.

These points are not meant to ignore queer readers/viewers of yaoi and yuri, though it has been noted that the vast majority of marketing and demand is for heterosexual audiences. With heterosexual fans and creators saturating queer stories, a less authentic view of the LGBT community arises. One cannot mention yaoi and yuri without acknowledging manga fanworks or doujinshi often created to portray preexisting characters in queer relationships. The greatest market for yaoi and yuri exists within these fanworks, but given the production and distribution of anime, it’s unlikely that fandom plays a role in the influence of queer themes in canon works. That being said, it’s important to note that fanmade doujinshi also tend to adhere to the harmful stereotypes and tropes that demoralize the queer community, as well as predominately being made by and for the heterosexual community. To this day, yaoi and yuri are still some of the only depictions of queer romance in Japan, but fans, queer and otherwise, have shown a hunger for more positive representations that don’t fetishize, demoralize, or present same gender love in dishonest ways. Queer fans of anime deserve better than what we have been dealt, thus we must set out to find positive representations and uncover why such anime have been censored by Japan and the United States.

Female/Female love in Sailor Moon

With 200 episodes produced by Toei Animation and airing from 1991-1997, Sailor Moon became the most popular series within the magical girl genre, and is considered an anime classic. Based on the manga by highly talented female writer, Naoko Takeuchi, Sailor Moon recounts the story of Usagi Tsukino, a high school girl empowered with magic to become Sailor Moon and fight villains threatening the universe. Usagi fights to save humanity with her other planet-named friends, the Sailor Scouts (Note: If you only watched the English dubbing version, Usagi’s name was Serena). With a cast of over eight strong female characters, the series contains themes of feminism and empowerment, while also following romance tropes of the shōjo genre. Usagi herself is in an on-again, off-again romance with a male character, but this anime is notorious for its representation of the female/female relationship between two Sailor Scouts, Uranus and Neptune. This relationship was considered revolutionary for its portrayal and though Uranus and Neptune never kiss or openly state they love one another, they are icons for the queer community.

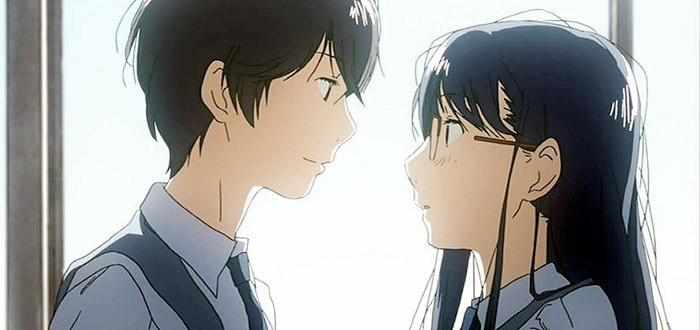

Uranus and Neptune were first introduced in the third arc of the anime in episode 92 titled “A Handsome Boy? Haruka Tenoh’s Secret.” In this episode, a handsome boy, Haruka, is lusted after by Usagi and Minako, aka Sailor Venus. Despite Haruka returning the girls’ flirtation, it is revealed that he is taken by a beautiful blue-haired girl named Michiru. To make things all the more complicated, by the end of the episode it is revealed that Haruka is not a boy, but a girl who dresses and acts very masculine. She is also Sailor Uranus, while Michiru is Sailor Neptune. Haruka and Michiru’s relationship is not portrayed in a negative or particularly humorous light; they are simply “together” as Haruka states. In episode 95, the two enter a “Lovers Contest” and when the announcer tells the contestants to call out their girlfriend’s name, Haruka calls for Michiru. The representation of this romance is noteworthy in the way these characters are drawn together, sharing obvious intimate looks, gestures, and holding hands. The dialogue they share is very romantic, and Haruka and Michiru often discuss their intimacy with one another. A level of unconscious censorship was enacted with the Japanese version of this series, as Uranus and Neptune don’t ever share a kiss, but Usagi and her boyfriend share about four onscreen kisses in the series (a high number even for heterosexual couples in anime). This censorship could be attributed to Japan’s bias against homosexuality still being worked through from the Meiji Constitution and Keikan code. However, when the series was dubbed and imported to the United States, the relationship between Uranus and Neptune was majorly censored.

When episode 92 aired in the United States on Fox Kids, the line Haruka used in the Japanese version to say she is together with Michiru is changed to say she is not with Michiru. During the romantic gazes, gestures, and hand holding, Haruka and Michiru assert they are just friends. Then, in later episodes of the American version of the series, the two are said to be cousins. In episode 94, Michiru discusses her first kiss was with a boy named Brad, while in in the Japanese anime, the kiss she refers to is between biblical Adam and Eve, not a kiss involving herself. In a Huffington Post article titled Sailor Neptune and Uranus Come Out of the Fictional Closet, Sara Roncero-Menendez discusses how this relationship was censored in the United States to avoid themes of homosexuality in a show aimed at young girls. So, rather than allow a very tame relationship between two young women be portrayed in the anime, the American network preferred to turn the romantic gestures of Uranus and Neptune into something totally different, even if the characters’ actions made the relationship near incestuous. Students from the University of Minnesota translated a 1996 interview from Kappa Magazine in which series creator Takeuchi stated, “The relationship between Haruka and Michiru is quite special… There’s not only heterosexual love, but there also can be a homosexual love, in this case between two girls.” She was not happy with the changes made to Haruka and Michiru’s relationship in the English dubbed version.

The censorship of Sailor Moon did not end with Uranus and Neptune. In the original anime, two male villains Kunzite and Zoisite were portrayed as romantically involved. They were cut in the American version. Sailor Star Fighter, who had a crush on Usagi and was originally female in the Japanese version, was changed to male in the American anime to make the attraction heterosexual. This censorship could be seen as another indicator of the American networks’ desire to avoid queer themes.

The good news about the representation in Sailor Moon is that in 2015, a reboot titled Sailor Moon Crystal aired in Japan and made it more clear that Uranus and Neptune are a romantic couple, and are not cousins. They share more romantic gestures in season three of the new anime and with it being aired online through the streaming site Crunchyroll, the series is virtually the same for Japanese and English speaking audiences. The new series is not without its faults, as there is an episode of Sailor Moon Crystal in which Haruka kisses Usagi against her will, which demoralizes same gender attraction in a sense, though the act is later apologized for. This case; however, shows that Japan’s steps toward queer representation are still baby steps. Overall, Sailor Moon and all of its iterations, is one of the most important anime in showing how queer representation is censored in Japan and the United States.

Male/Male love in Neon Genesis Evangelion

Back into the realm of shōnen, the classic mecha anime Neon Genesis Evangelion broke boundaries during its original 26 episode run between 1995-1996. Written and directed by Hideaki Anno and produced by Gainax, the series is set a decade after near worldwide destruction by massive creatures called Angels. The futuristic city of Tokyo-3 now uses giant robots piloted by teenagers to defend the world from the remaining Angels. This series was incredibly unusual for the way it subverted conventions set by the mecha subgenre, and in an interview in the special features of RahXephon Complete, Anno stated that he originally wanted the anime to follow traditional conventions, but he was happy that it became an “anti-mecha” anime because it contained more emotion that way. The main character of Neon Genesis Evangelion is Shinji, a teenager who suffers from depression and trauma caused by his emotionally abusive father and the death of his mother. Shinji is forced into piloting robots to fight against the Angels, but this piloting physically hurts his body and creates more trauma. Throughout this series, several female characters try to form romantic relationships with Shinji, but he is fairly unresponsive to their desires. One could assume Shinji’s apprehension toward the women in his life is caused by his mental illness and mommy issues, but on several occasions he shows an interest in sexuality, wishing to be kissed and discussing masturbation. According to Thomas Lamarre, author of The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation, this anime was notorious for its lengthy time taken between aired episodes, mostly due to Anno’s own depression and lack of funding, but episode 24 of the anime, “The Beginning and the End, or ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’,” was a major change for the series and for Shinji’s character.

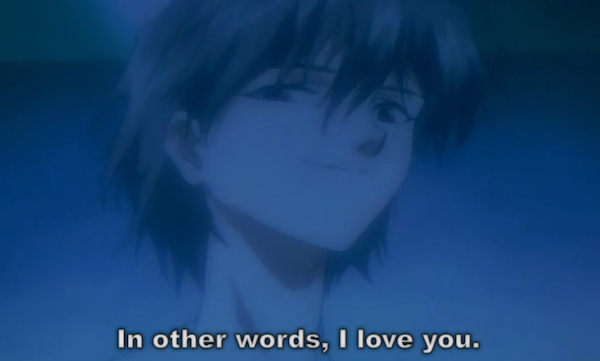

In episode 24, the character Kaworu is introduced as a replacement pilot, and instantly he and Shinji form a bond. The two spend time alone on the shores of the city, then Kaworu and Shinji take a bath together in private. Historically, bathhouses have been known as havens for the queer community in Europe and the US, though onsens and communal bathing is far more common in Japanese culture than in the West. It’s in the bathhouse that Shinji’s romantic attraction to Kaworu is strongly hinted at; at one point Kaworu suggests they go to bed together and Shinji blushes. One could read the bathhouse scene as an implication of sexual content, but the way the animation is drawn, one can only see the boys from the chest up. Toward the end of the bath scene, Kaworu tells Shinji he loves him.

This declaration of romantic feelings is a big deal as such open expression of romance is shied away from in Japanese culture. Much like the queer relationship in the original Sailor Moon anime, Shinji and Kaworu never kiss, but by the end of the episode when it’s revealed that Kaworu was a nonhuman agent of the Angels, Shinji is forced to kill him while piloting the robot. Shinji later says that he loved Kaworu, too. This tragic ending and dehumanization of a queer character reflects Japan’s attitude toward what is considered sodomy and shows the unconscious censorship of queer romance in anime. However, episode 24 created an even bigger stir with censorship, because around the time this episode aired in Japan, Neon Genesis Evangelion lost its funding. The last two episodes of the series, 25 and 26, have been widely criticized for their haphazardly pieced together visuals, abstract concepts and heavily internal psychoanalysis. There has been much debate on this subject and the studio’s reasoning, but given the content of 24th episode and the timing of the studio’s choice, one could imply that censorship was made over the queer relationship.

When Neon Genesis Evangelion was distributed to American audiences, controversy came from a different standpoint and forced certain visuals from the series to be censored. The series contains strong Christian themes and imagery, including crosses and biblical names. In the controversial last two episodes of the series, Shinji sees one of the Angels nailed to a cross, its face twisted and its body bloated and inhuman. This image was censored by some American networks and did not air. Oddly enough, the relationship between Shinji and Kaworu remained relatively the same in the American version of the series, probably due to its already vague nature.

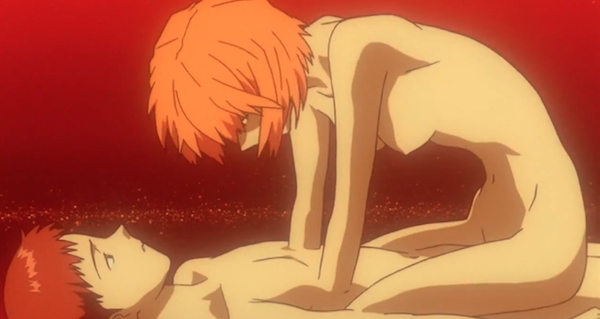

Hideaki Anno insisted the choice to make the last two episodes so abstract was intentional, but in 1997, two films Death & Rebirth and The End of Evangelion were made to rectify the ending of the series. The End of Evangelion contains stronger sexual content than the anime series, particularly an imlpied shot of Shinji masturbating over the unconscious body of Asuka, a female character, and a highly surreal image of naked Shinji being straddled by Rei, another female character, also nude.

The image of Shinji and Rei resembles sex, but after a moment of this surreal coitus, Shinji states, “But this isn’t right. This feels wrong.” Shortly after, the film cuts to Kaworu once again asserting the words, “I love you” to Shinji. Though this instance isn’t a confirmation of Shinji’s sexuality, it suggests he prefers men, or is at least on the bisexual/pansexual spectrum. This series and its films showcase an attempt by the shōnen genre to address queer representation and the censorship that got in the way.

Changing attitudes with Yuri!!! On Ice

Highly regarded as the crowning glory of queer anime, Yuri!!! On Ice is a recent series that will go down in history as a major game changer. The anime was written by Mitsurō Kubo and directed by Sayo Yamamoto, two women who got the series licensed by Crunchyroll in 2016. This series was marketed as a shōnen within the sports subgenre as it follows 23 year-old Japanese figure skater Yūri Katsuki in his journey to revitalize his skating career. From the first episode, Yūri is portrayed as having an obsession for gold medalist, Viktor Nikiforov, an older Russian skater. Viktor agrees to coach Yūri in his quest for a gold medal. Intimacy develops between Yūri and Viktor with strong hints of sexuality and romance. In the second episode, Viktor bathes in the Katsuki family hot spring and displays his naked body to Yūri.

The visuals of this scene situate flora over Viktor’s groin to censor his genitals. A cut away from this image shows Yūri blush. In later episodes, Viktor asks Yūri about his romantic history, sleeps with him in his bed, and casually strokes Yūri’s face during and outside of skating practice. Early on, this anime defied conventions of the sports genre and dipped into tropes of shōjo, focusing on the subtextual romance between Viktor and Yūri. The construction of this romance can be compared to the relationship between Uranus and Neptune in Sailor Moon, but with two males, one of which being the anime’s protagonist. It is important to mention that unlike Sailor Moon and Neon Genesis Evangelion, Yuri!!! On Ice was distributed to Japan and the United States at the same time through online streaming. However, even with such a modern anime that seemed to break major boundaries, censorship of the queer relationship still occurred.

Episode seven of Yuri!!! On Ice caused a major stir amongst Japanese and American fans alike when an implied kiss between Yūri and Viktor aired. The kiss takes place after Yūri has skated a successful number and Viktor embraces him in celebration. The way the kiss is drawn shows the men coming together, but Viktor’s arm blocks their mouths. The scene then cuts to an over the shoulder shot of Viktor leaning in and Yūri’s eyes closing, a blush at his cheeks.

The kiss is highly implied, but censored in the visuals. This scene has caused major controversy, as some believe the two are merely hugging, while others believe it was a cheap move to imply a kiss and not show it full on. To complicate things, episode ten shows Viktor placing a golden band on Yūri’s left ring finger while the two visit a church. Viktor insists it is a “promise ring” that promises a gold medal, and even when their friends assume the men have just been married, Yūri asserts this is not true. In the last episode of the series, Yūri jokes with Viktor about getting married in the event he wins gold, but when he does not win gold, they remain in ambiguous queer limbo.

Viktor and Yūri are not the only ambiguously queer characters of the series. Yūri’s young rival Yuri Plistesky shares a relationship with another man in an even more vague depiction than the relationship Viktor and Yūri presents. A highly sexual character, Christophe, is obsessed with butts and often orgasms mid-routine. In the eleventh episode, Christophe is shown at his apartment with another man who comments on how he “always comes early” perhaps implying a sexual relationship between the two.

Although Yuri!!! On Ice presents what seems like progressive queer representation, the relationships are continuously written and drawn to be ambiguous, thus emphasizing Japan’s assertion that the queer community remain in the closet. The creators of the anime have never confirmed the romance between Viktor and Yūri, stating on Twitter, “In the end we’re not going to tell anyone what to think, or rather, compel anyone to interpret it in a certain way. So please decide it for yourself.” (Kubo) However, with an animated film suspected to premiere by 2019, we can hope for some answers to the ambiguity.

Is there any positive queer representation in anime?

With the dubbing censorship of Sailor Moon and the cutting of funds for Evangelion, as well as the visual and narrative ambiguity of Yuri!!! On Ice one may wonder if there are any positive examples of queer relationships in anime. The recent 2018 remake of Cardcaptor Sakura continues the subtextual background relationship between two high school aged boys and the unrequited attraction of one young female character for another. Sound! Euphonium (2013), an anime about a high school concert band rewrote the manga’s relationship between the main girl and a boy so the protagonist’s attraction was directed at another girl instead. Puella Magi Madoka Magica (2011), a subversion of the magical girl genre, shows girls kissing other girls despite a tragic plot and ambiguously platonic relationships. Aoi Hana (2009) portrays a relationship between young queer girls coming to terms with their sexuality. Wandering Son (2011) depicts two middle schoolers discovering their transgender identities and experimenting with queer romance. These anime are all fine and good in their own ways, but I feel one in particular reaches rather high on positive queer representation in anime for its complexity and authenticity. The best example I can find of non-sexualized, well-rounded queer representation in anime is the Studio Bones series No.6.

Based on a novel series and manga by Atsuko Asano, the anime No.6 is set in a walled-in, dystopian city called No.6. The series follows sixteen year-old Shion in his discovery of the government’s brainwashing of its residents, as well as the scientific experiments No.6 has done on a goddess-like bee spirit. Shion is saved from imprisonment by Nezumi, another boy his age who fosters a hatred for No.6. Throughout the series, Shion and Nezumi uncover the evils done by the government, infiltrate the facility where they keep the bee spirit and eventually set her free, taking down the city walls in the process. During the adventure, Shion and Nezumi develop a romantic relationship, and despite dangerous situations that complicate their intimacy, the series does not shy away from the queer representation of these characters.

In the first episode of the eleven episode series, Shion’s female best friend, Safu, asks him to have sex with her, to which Shion is visibly flustered and turns her down, already hinting at his sexuality. Throughout the rest of the series, escaped Shion and Nezumi live together in a bunker outside the No.6 walls, share two onscreen kisses and profess their romantic feelings for one another. At one point, Nezumi tells Shion he should leave because of his desire to save No.6, but Shion cannot because he “is drawn to Nezumi.” The Japanese translation of this line closely resembles the phrase “I love you” and it can be assumed Shion’s words hold similar meaning, despite the current society’s apprehension to say those words. This could be an example of Japan’s censorship of romance, though stripping away Western society’s standards of love to see the Japanese standard is important here. On various occasions in No.6, Nezumi tells others that Shion belongs to him, and Shion continues to profess his attraction through phrases similar to “I love you.” Nezumi often pets Shion’s face, strokes his hair, and makes sexual innuendo jokes when the two are in private. Nezumi is also a member of a theater group and regularly performs in drag, echoing a positive aspect of the gay community from real life. Shion and Nezumi are willing to kill for one another and by the end of the series, they share another onscreen kiss after taking down the No.6 government.

According to the anime creator, Shion and Nezumi are in a romantic relationship. Asano stated in a 2011 interview, “I like writing about the connection between people of the same sex, not limited to boys. With the opposite sex, the two of them being drawn to each other results in romantic love, like a married couple….” and when asked about their kiss, she responded, “I was trying to show that Shion is incredibly in love with Nezumi, and that Nezumi is extraordinarily drawn to Shion.”

However, No.6 is not entirely clear of censorship, though the anime is a unique case that subverts the typical censorship of queer representation. The manga of the series shows images of Shion and Nezumi sharing a bed together, flirting more, and further professing their attraction to one another. It could be said that in the adaptation of a long manga, certain aspects of the relationship had to be cut to save on money and time. At the end of the manga, Nezumi leaves Shion and after three years, has never returned to him. The anime does not reflect the same tragic ending of the manga. In the last episode of the anime series, when Shion and Nezumi make it out of the facility and see the walls of No.6 have fallen, Nezumi kisses Shion on the lips and the shot cuts to Shion looking out at the newly opened up city. The anime never clarifies if Nezumi left him, nor does it cover the three year gap of the manga’s epilogue. In this way, the anime may actually show a more positive depiction of the relationship between Shion and Nezumi than the manga. The anime censors the melancholy of the manga’s ending and opts for a more positive representation of the queer relationship.

An unfortunate part of No.6 ‘s history in the anime industry is how underappreciated the series is. The novels have never been officially translated to English and the manga is very hard to come by. Many anime fans have dismissed this series due to its serious themes and dystopian setting. The series also suffers from a genre mix that is hard to market within the anime industry. Like Neon Genesis Evangelion, No.6 is a science fiction series that deals with dark topics like genocide, brainwashing, and mental illness. However, the series also features heavy handed romance and was categorized as a shōjo when originally produced. This classification created confusion among readers and viewers because of the lack of a female protagonist or common conventions of the shōjo genre. No.6 has since been claimed as shōnen-ai, the adult version of “Boy’s Love.” Unfortunately, the series is still widely unknown to the anime community.

What do we do now?

In January of 2018, I conducted an anonymous online survey of over 200 anime fans. 35% of surveyed individuals said anime negatively represented queer relationships, 52% said anime was somewhat positive in its representation, and only 5% of surveyed individuals said anime represented the queer community positively. Many respondents discussed how representations of female/female relationships are more common in anime, but can be easily dismissed as platonic because of society’s view of female romance. Other responses talked about how stereotypical many queer male characters are in their portrayals, often being made into predators or feminized for comedic effect. One response said, “MLM are more likely to be portrayed as disgusting or creepy. WLW are more likely to be portrayed as either childish or sexually appealing.”(Note: In this case, MLM is “Men who Love Men” and WLW is “Women who Love Women.”) Another respondent stated, “There are rarely anime that explore sex or sexuality in general as anything more than pornographic or exploitative… And when an anime DOES tackle the topic of sex or sexual interests it’s in a non-explicit or unhealthy way.” These responses shed a light on the ways fetishizing in yaoi and yuri bleed into anime. 88% of the respondents to my survey identified as being somewhere on the queer or LGBT spectrum, which shows that while anime attracts marginalized communities, there is a lot of work to be done in how it represents them. The responsibility of the anime industry to acknowledge its queer fans lingers as sexuality is still a taboo topic in Japan, and other parts of the world, including the United States.

There are currently no major laws against homosexual activity in Japan, but same sex marriage is not yet legal at a national level. Sexual orientation is not a protected class in the human rights code, but in recent times, Japanese celebrities and politicians have openly come out. A Japanese journal recently wrote about this year’s Tokyo “Rainbow Pride” Parade bringing over 7,000 marchers and about 150,000 attendees to the festival celebrating sexual diversity. This was a record high. There is genuine hope for change in the treatment and representation of the queer community in our world and the anime world, and for that reason I feel confident opening the door of my own closet to bring awareness, demand positivity and insist we no longer settle for censorship.

Works Cited

Anno, Hideaki. Neon Genesis Evangelion. Gainax, Tatsunoko Production, 1995.

—. The End of Evangelion. Gainax, Production I.G/ING, 1997.

—. RahXephon Complete, interviewed by Yutaka Izubuchi. Section 23 Films, 2003.

Asano, Atsuko. NO.6 Complete Guide. KoÌ Dansha, 2011.

Bennett, Nicholas. “Queer Representation in Anime.” Questionnaire. SurveyMonkey.com. 2018.

Brenner, Robin E. Understanding Manga and Anime. Libraries Unlimited, LLC, 2007.

Fox, Emily., Makousky, Nadia., Polvi, Amanda., & Sorensen, Taylor. “Naoko Takeuchi, creator of Sailor Moon.” Voice from the Gaps. University of Minnesota, 2009.

Kon, Chiaki. Sailor Moon Crystal, created by Naoko Takeuchi. Toei Animation, 2015.

Kubo, Mitsurō. Yuri!!! On Ice. MAPPA, Crunchyroll, 2016.

@kubomitsurou. “ 結局は誰にも教えてないというか7話のことは誰にも押し付けてない ので自分の判断で決めつけてくださいね” Twitter, 8 Dec. 2016, 4:01 a.m., https://twitter.com/kubomitsurou/status/806831104825008133.

Lamarre, Thomas. The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation. University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. “The Invention and Reinvention of ‘Japanese Culture’.” The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 54, No. 3., Association for Asian Studies, 1995.

Nagasaki, Kenji. No.6, created by Atsuko Asano, Studio Bones, 2011.

Nakajima, Maki. “Record Number of 7,000 People March in ‘Tokyo Rainbow Pride’ Parade.” The Mainichi, General Digital News Center and Miyuki Fujisawa, 2018.

Pflugfelder, Gregory M. Cartographies of Desire: Male-Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse 1600-1950. University of California Press, 2007.

Roncero-Menendez, Sara. “Sailor Neptune and Uranus Come Out of the Fictional Closet.” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 2016.

Satō, Junichi., Ikuhara, Kunihiko., & Igarashi, Takuya. Sailor Moon, created by Naoko Takeuchi. Toei Animation, 1992.

Suan, Stevie. “Anime’s Performativity: Diversity through Conventionality in a Global Media-Form.” Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal. Vol. 12. Graduate School of Manga Studies, Kyoto Seika University, 2017.

Tamagawa, Masami. “Coming Out to Parents in Japan: A Sociocultural Analysis of Lived Experiences.” Sexuality & Culture. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 2017.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Until recently, LGBTQ was a taboo topic in Japan. The older generation tends to not look upon it favorably whereas the younger generation is in favor of marriage equality. I have a friend from Japan whose parents basically disowned her when she married another woman.

So sorry to hear about your friend being disowned – a very sad reality for LGBT+ folks in many parts of the world.

This article was awesome. Thank you for writing it and thanks to this publication for highlighting it. Throw your queer anime/manga recommendations at me!

Thank you for reading and for the compliments! I would recommend any of the main anime/manga analyzed in the article with emphasis on No.6, Aoi Hana, and Wandering Son. I have not yet finished it, but My Brother’s Husband is a manga with a gay dad that involves real world issues around the subject of the LGBT+ community.

You are again talking about works that you do not know. MC in Brother’s Husband is not gay, gay is his brother. Well, that is logical from the title. The author even said in an interview that he made MC straight to appeal to the audience of straight men and show them the situation from a more understandable position.

Okay John, you’re right about the father in the manga, he is not gay. I misspoke, sorry if this somehow offended you. If one were actually to follow my recommendation and look up this manga, they would surely figure it out without needing your conceited comment as clarification.

You can give me an adjective like “conceited” or “selfish” as much as you want, but this does not cancel the fact of an error.

I recommend Hourou Musuko. Probably the best queer anime that will be made for a good few years at least. Main character is a transgender girl, her best friend/crush is questioning somewhere between whether they’re a tomboy, nonbinary or male, the girl that has a crush on the MC is struggling with her sexuality, the MC’s best male-friend is out-homosexual, one of their classmates occasionally attends school in a boy’s uniform etc.

Aoi Hana. Adapted from a manga that’s written by the same author that wrote Hourou Musuko. Therefore, that similar excellence is carried through. There are several characters of differing sexualities, but the anime adaptation mostly focuses on Fumi’s coming out and first girlfriend.

Doukyuusei is a good representation of the BL genre, it’s a fairly short movie if you want to get yourself accustomed to it.

A great film for sure, but I would warn for adult sexual coercion of a teenager, as that content may rightfully upset some folks.

“Flip Flappers” is a queer girl’s coming-of-age story and accepting her identity. It masterfully and ironically uses “subtext” to tell this story. AND no fanservice. =)

If this show does not have fan service, then I don’t even know what you think is fanservice. For example, the BD edition of the show was distributed with an interview with the director, where he called yuri one of his favorite fetishes.

If you are into the arthouse scene, try Yuri Kuma Arashi. Basically an attempt at deconstructing the patriarchal Class-S oppression system that has marginalised and belittled lesbians, despite also offering some feministic empowerment, since its inception. It uses deep levels of irony and some people are on the fence of whether it goes too far in one way or the other, thus begging the question if it’s truly as satirical as it wants to be, or accidentally becoming the thing it is criticising.

Class S – the patriarchal system? LOL what? This phenomenon was literally created by feminists with the participation of Japanese lesbians and was largely based on the idea of the freedom and youth of the girls of that time in front of the pre-war patriarchal Japan. To call Class S patriarchal or homophobic, means to show your flashy ignorance and a complete lack of knowledge about the nature of the phenomenon. Not to mention that one of the main authors of the genre was Nobuhiko Yoshia, an open lesbian and the mother of Japanese lesbian literature.

Hey John, don’t attack commentors on my article. You are not the authority on these issues, so get off your high horse.

You can manipulate emotionally charged words for as long as you like, but this does not negate the fact that calling the feminist-lesbian genre as patriarchal is rather ridiculous.

Super Lovers and Hitorijime My Hero are recent, not that great (though the latter is much less offensively bad than the former) series, so worth checking out if you want an introduction to common queer tropes, though it should be said AFAIK is more of a manga based industry.

Not an anime, but the Japanese visual novel The House in Fata Morgana has large section on a transgender character.

Read Ganbare Nozomi-kun, Sabishisugite Lesbian Fuuzoku ni Ikimashita Report, Love My Life, New York New York, Blue Sky Complex, What did you Eat Yesterday, Shimanami Tasogare, and Umibe no Étranger. 🙂

Sorry, can’t edit my comment. Ganbare! Nakamura-kun!! that is what I meant. lol.

Eruna from Mikagura Gakuen is one of my all time favorite queer characters. She is a lesbian main character in a non-romance anime. She is far more than her sexuality and has some very ridiculous moments, and singlehandedly makes what would actually be a trashy anime very easy to watch because of her fun personality.

Thank you for bringing up Eruna. I’m glad she makes an impact.

This. It’s really refreshing to see a main-character being gay without any angsty strings attached.

In the yuri genre, I often hesitate to call characters LGBT, due to the nature of moe yuri and how f/f relationships among schoolgirls in particular are represented historically in Japan.

Totally agree with you there! Yuri and yaoi can be majorly problematic, and the portrayal of young girls in yuri is at the top of the problem list. I did some research on the age of consent in Japan, though it did not fit into this essay, but I wonder if there’s a potential article waiting to be written about this issue…

Most true yuri are essentially trying to get out of that best-friendship-training-for-men hole, though (even some moe f/f are trying, like the recent Hina Logi). Whether it’s Aoi Hana, (manga but) Girl Friends, Sasameki Koto, Yuri Kuma Arashi, hell even the male-demographic aimed Kananzuki no Miko and YamiBou to an extent…

Great article. I can definitely relate. A recent observation. In the manga of Boku no Hero Academia, there are two trans characters. And it’s just another normal fact about them, without any reliance of the plot. And that is the way it should be. They are people just like every other character in the story, and just one arguably controversial info on them isn’t gonna change anything.

Thank you! I do really appreciate those characters in BNHA, though watching the anime alone wouldn’t give a viewer much insight into those parts of their identities. I hope Tiger especially gets more story in the future.

I think sexuality is major in Japanese culture and they aren’t known to having same sex relationships on tv and cartoons while America is very open and ok with that.

You’re very right, and I discuss Japan’s culture with same gender relationships quite a bit in the essay. I would say that the US is moving in the right direction with its Queer Rep, especially as of late with Steven Universe, but the US is certainly not at the point of being wholly okay with such. Networks still fight very hard to squash this sort of representation, and when we do see it in films and TV, it is often used as a marketing ploy to make an insincere impact.

As someone who grew up queer and a fan of anime, I struggled to find much queer representation. Thanks for your perspective.

Thank YOU for reading!

It’s a great time for queer anime and manga fans, and queer fans have themselves to thank. So pat yourself on the back — you all deserve it!

Interesting treatment of this topic. I want to note that some of the terminology and treatment of traps in anime is harmful, both to crossdressers but especially the already vulnerable transpeople.

You are absolutely right. I made a choice to discuss same gender romance and censorship in this piece, but as a trans person myself I care very deeply for the representation of gender nonconforming folks in anime. Perhaps that will be my next piece.

Every now and then, there comes an anime that either touches on or dives fully into LGBT themes, without clear indicators that it’s aiming for either the fujioshi audience or the usual yuri fans. These are the ones to look for.

Some examples include Aoi Hana and Hourou Musuko, off the top of my head.

There are some worse case queer representation I have seen. For example Netsuzou TRap. God. I don’t even want to get started but I think it’s a shithole with no redeeming qualities whatsoever, made even worse by the fact that it only exists to pander to fetishists who get off on sexual abuse, cheating, and lesbian relationships.

And then there is the other side of the coin, like Aoi Hana.

I agree it’s not like… good.

But have you read the manga? The idea of a girl being pulled in multiple directions, because of this whole best-friendship-training-for-men Class S bullshit, and because of the abuse, and her actual repressed feelings, does sometimes makes it a somewhat compelling character arc. At times. I think some of the steamier scenes are drawn with too much fanservice though…

But the anime wasn’t so good, and if you haven’t read the manga, then I can understand why you feel that way. Even if you’ve read the manga, I can understand how you feel that way, but I wouldn’t quite say it’s the worst even then.

Don’t write about Class S if you don’t know what it is. Not only was open lesbian and the mother of Japanese lesbian literature, Nobuhiko Yoshiya, one of its main creators, but the genre itself was created by feminists to idealize female friendship, sisterhoods and opposing their bonds to the “male world” of the then patriarchal Japan.

And this genre was not created for abusing and “suppressing” lesbians, it existed only in the 20-30s due to the fact that the existence of female education exclusively in the form of all-girls school led to the widespread situational homosexuality and homosociality, because of which friendships between girls often became very passionate and emotional.

As the schools became collaborative and the teens returned to normal interaction between the sexes, the Class S disappeared. However, many authors, both girls and boys, still use its elements to depict spiritual love and idealized friendship, something that ignorant people like you often take for “yuri subtext” and “qeer coding”.

You clearly have some knowledge of this topic, John, as evident by your manslpaining. One can and should be critical of these genres and works, especially if they make one uncomfortable. Your point of view is not the only one in the world.

Criticism of what you do not know and do not understand, has a rather low value, don’t you think so? Not to mention that calling Yoshiya patriarchal is tantamount to Trump’s naming of a liberal, lol.

Lesbians are people too, and they can also cheating, be immoral or vulgar. This is an important point and the desire to see representation solely as the creation of an illusion about ideal people, only creates new stereotypes, rather than trying to destroy old ones.

Hello, John; this is a great point, and you are absolutely right that those traits and actions are not exempt from a person by way of their sexuality. However, as this lovely article points out, anime largely lacks the positive and “ideal” representation of queerness in the first place; there is currently no illusion to shatter within this form of media. Unless an individual has already been exposed to positive displays of some of the many different forms of sexuality, wouldn’t starting with more negative demonstrations only work to villainize them? Given the attitude of the general global population towards non-heterosexual sexualities, even now, it seems that the world would benefit much more from ideal representation than realistic. Is it not much easier to descend from idealistic views than to illustrate the good in something that has been so thoroughly soiled?

I think a lot of lesbians I know identify with a lot of the female characters in Sailor Moon (There’s a lot of being…affected? by the beauty of other girls in it.) Whether they’re intended to be sorta bi, I’m not gonna look into that.

I have a lot of lesbian and WLW identifying friends who would agree with you there!

great

Thanks!

The representations are generally pretty poor. Any good gay character almost always falls into the super camp peacock who is like a big sister or used for jokes with unwanted physical advances on straight MC. And so on. With that being said, I really value the representation in Utena and Tokyo Godfathers.

Great points for sure

Do not confuse LGBT representation with the Japanese concept of akogare and the theme of admiration in general.

Do not confuse hiding behind a computer screen to write your arrogant and self-righteous comments invalidating a minority community’s reading of anime series as having any power, John.

There’s a lot of subtly LGBTQ+ characters in anime, more than any other medium for sure.

Positive representation is essential. Although it’s not that hard though – all we want is queer characters that go beyond tropes and simply being queer, and preferably being main characters.

Heck yeah!

I’m a bit sick of the psycho-lesbian rapists. Very occasionally, I can get behind them when they are made sympathetic enough… but sometimes it’s just simply not enough. Hotaru from NTR is essentially this.

Sensei from Doukyuusei is also a top-tier offender for similar reasons, and sought to ruin an otherwise excellent queer movie.

Queer representation is important. We can’t get past it if people do not understand or see these groups as individuals. It’s also important as to not teach kids to see these issues as jokes or children who may feel this way are meant to die tragically or live in misery.

Agreed 100%.

Nice work Nicholas. I very much value Evangelion for being such a popular series and the fact the lead is already surrounded by several attractive girls.

Thank you!

Damned fine article. It opened my eyes to a few aspects of anime of which I was previously unaware, so thanks for that. We live and learn.

Thank YOU! Glad I could provide some education.

To add to this article, there’s a transgender person in Cowboy Bebop (ep 12/13) – that particular anime also has a scene where Faye stumbles in on two gay men making love – and there is no negative connotations to the whole bit, and she simply moves on with her mission.

That may not sound amazingly progressive by today’s standards, but considering this was aired in 1999, I was very impressed that it was so tastefully done.

If I remember correctly, the trans character in Cowboy Bebop was forced to transition because of an experiment that altered their hormones, and afterwards they still referred to themself as their former pronouns. I don’t know if I would call that representation impressive, since there are several older anime that throw in queer and gender nonconforming characters for one off episodes, much like this example.

I’m glad that this article is getting people thinking, though! The more we think back on these representations, the better we can critique and learn from them.

I feel Yuri on Ice is easily the most important anime for this subject in recent years, perhaps ever.

I know this is partially off-topic, but I would just like to recommend that anyone interested in manga should take a look at a sort of “revolution” taking place in the East Asian comic industry regarding self-published comics webcomics (sometimes called webtoons). Independent artists/authors in Japan, South Korea, China, Taiwan, etc. are self-publishing uncensored comics online– some of which contain realistic representation of queer characters and stories (which might have been censored or not picked up by publishers had the authors tried that route.)

If anyone is familiar with the Japanese webcomic “Husky and Medley” from a few years ago, the concept and design of these webcomics is similar to that. Also I HIGHLY recommend Husky and Medley in general. It’s a lesbian webcomic based on the author’s own experiences.

My other recommendation in the webcomic genre is the Chinese manhua “SQ: Begin W/ Your Name!”, also called “Their Story” and “Tamen de Gushi”. It’s a Chinese lesbian high school slice of life that is just SO cute and funny and realistic.

Anyway, it’s yet to be seen how to properly give money to these amazing creators, especially since the only way people in the West can access them is through “fanlations”. But it’s really refreshing that comic artists on the Internet are giving us these uncensored stories in spite of them not being properly published.

As with anything, there are also billions of these webcomics that are abusive and problematic— the nature of the beast with self-published stuff AND the Internet. I’d urge anyone to proceed with caution, read reviews and tags, etc. But I’d just like to mention that this phenomenon exists and might be a sign that better queer stories in East Asia are being told.

Haruchika is a relatively recent one with a gay kid crushing on a teacher (Which is like…normal in japan? I mean, I feel like it’s normal in the US too, but not for depiction in media. Not the gay part, the teacher part.). I don’t think it was very well received or popular, though I assume that isn’t related to gayness. I recommend it to readers of this engaging article.

Is it weird that my young self always new that Neptune and Uranus where 100% in love with each other. They were always my favourite couple even back when I was 8. I guess censorship didn’t work that well, or maybe it was different for Canada, not sure.

Another show that has somewhat of a good queer representation is the Nanoha series where Fate and Nanoha basically end up having a kid together by the third series. But much like Uranus and Neptune’s story, them being an official couple is never truly made explicit which is unfortunate. This was a really cool article, here’s hoping that more queer representation will be present in both anime and cartoons.

I like manga and anime, but I’m not really affected by the sexualities of the characters other than my own personal preferences. Representation is important, but LGBT representation is such a small part of that.

Good stories should resonate with people, powerful stories often happen when you see a part of yourself reflected in a character. But that’s not going to happen with me if the only part of myself I see reflected in a character is the fact that they’re gay.

That’s like expecting a character to resonate with me because they have blonde hair. It’s more important that their actual personality and character resonate with me than their sexuality. That’s what I feel representation should be about- a character representing real personality or character traits that people actually have. I don’t want to just see an anime character on screen, I want to see a person, an actual person. Sexuality has like….next to nothing to do with that for me. Sure, character moments I relate to can come out of conflicts directly related to sexuality, but I’m not going to feel represented by a character just because they’re gay.

It’s a little more complicated than that.

Lovely post. You might be interested in researching some of the themes behind Kunihiko Ikuhara’s Yurikuma Arashi (literally Lesbian Bear Storm) which tries to speak to social issues within Japan around this topic. His works are some of my absolute favourites and tend to delve into similar themes.

I highly recommend watching Hourou Musuko, it’s easily the best form of media I’ve ever watched regarding transgender issues.

LGBT in anime is a niche genre. Good to see it growing.

Outstanding work with this article! Thank you for sharing your story with us, while enlighting Japanese culture and its role in anime. I think a lot of the time we forget to explore material within its original context and lose understanding of why things are done a certain way. Very informative and definitely helps to bring another critical lens not only to anime, but to how lgbtq+ is treated globally.

Excellent discussion! I learnt so much, I knew very little about Japanese queer culture and its influence on anime, this was really insightful and so thoughtfully handled. The overall article was an excellent conversation and respectfully raised a number of key points that illuminate how difficult still it is to have equality in sexual representations in popular culture. Thank you very much for writing this.

Stuff I watch involve girls getting very friendly with eachother but it’s usually just used as a device to titillate the primarily male audience.

Yeah, the cliche of the schoolgirl molesting her busty compatriots is certainly overblown, and there’s nothing wrong with that: however, it becomes less amusing when you realize that this is actually a pretty big problem in Japanese society, and then you understand its prevalence.

Interesting article! I wonder if the average anime fan picks up on LGBT themes in the animes they watch, because I personally haven’t noticed some of the subtle clues hinted at in some of the more popular series that I’ve watched. After having read about some of the clues you pointed out, I can see it now though.

What an interesting article! I feel like I got schooled with a history lesson. I didn’t realize same sex marriage wasn’t legal in Japan yet. This seems odd to me–maybe just because of their vibrant culture. Or, seemingly vibrant. Tokyo is really my basis for saying this.

The series that came to mind when I saw the title of this article was Junjou Romantica (basically an MLM series), and while I didn’t fully realize it when I was younger, two of the three couples had a very predatory element to them. Now that I’m more aware of the history of queer representation in anime, I’m definitely going to be looking everywhere for it.

I loved this article! As a member of the LGBTQ+ community myself, it is very very interesting to close examine how the community I identify with is represented in a medium that I’ve pretty much grown up loving. Thank you so much for writing this 🙂

Wonderfull.

I am bisexual and a fan of anime (seen over 900) and a fan of manga (read over 300). For me, Gravitation was the anime that made me feel comfortable with myself. Sure, it has problems. But no representation can ever represent everyone.

Neon Genesis Evangelion is one of my favorites and I kinda feel tragic stories are an important part of being queer to be honest… Being bisexual is a lot like being Shinji to be honest. You really can’t be everything to everyone sadly…

Both of the characters in the manga version of Gravitation do state that they are bisexual (I think the the anime version, only Eiri says he is bisexual). And for me…. that is worlds better than most representation I get regardless of actions. I found the way things were talked about to be accurate with things I have read about Japan’s queer culture. both the anime and the manga contain a coming out scene. Which is highly uncommon in the over 400 yaoi/shonen ai stories I have read and watched.

Coming out itself is considered taboo in Japan. And the idea of being born gay is kinda not there. It is more of a state of being… much like how Shinji tackles things I guess. He is gay when he is gay and he is straight when he is straight. And there is no bisexual inbetween. Shinji, like many bisexual people… are forced to kill their gayside….

I highly recommend watching “Magical Girl Raising Project” as it includes a canon lesbian romance in which they’re at least cohabiting and act married. Also, there’s grounds for claiming another lesbian romance if the subtext for one character is read to indicate that she’s transfemme.

Loved this article. I think it’s really important, especially for younger people to see LGBT+ relationships in mainstream media.

Voy a escribir en español, lo siento :'(

Me gustó tu artículo, pero creo que malinterpretaste el mensaje en Revolutionary girl Utena. En la serie las escenas de violencia y abuso sexual se usan como crítica y no para avalar dichos comportamientos. Además, parece que no tomaste en cuenta los simbolismos sobre la madurez, ni tampoco la crítica hacia los roles masculinos y femeninos impuestos por la sociedad que presenta la serie. En la película queda más claro el simbolismo de la madurez, además de desarrollar de mejor manera, y de forma más explícita, la relación amorosa de Anthy y Utena. Sin embargo, la película es tan surrealista que te deja con cara de WTF XD

Con respecto a End of Evangelion, te olvidaste de mencionar el momento en que Kaworu (ya en la fusión Rei-Lilith-Kaworu-Adán) aparece ante Shinji para bajar su escudo AT. Con lo cual se terminaría de afirmar que él era la persona más amada para Shinji. Más canónico imposible.

Espero no incomodar con mi comentario.

¡Un saludo!

Thank you for your in depth comment; you are not a bother at all!

Revolutionary Girl Utena was not a main focus of this article, hence why I only wrote about two lines on the series. Regardless of the symbolism of maturity in the anime and film, these works are centered around abuse and enslavement — that is the core of Anthy’s character from start to finish, and it is very unsettling for an entire series to treat a woman of color as such, so consistently, without granting her decent happiness in the end. I am aware of the realities of this experience existing in real life, and I do not intend to discount the anime’s powerful messages and relevance particularly to survivors of abuse and the queer community, but Revolutionary Girl Utena falls into the unfortunate category of a tragic queer story, thus not providing positive representation — in my opinion.

I feel your point about Kaworu in The End of Evangelion is totally fair, as well! I believe any time Kaworu is included in the series (anime or films), he is doing something to validate Shinji’s love of him.

“Sound! Euphonium (2013), an anime about a high school concert band rewrote the manga’s relationship between the main girl and a boy so the protagonist’s attraction was directed at another girl instead.”

You really should read more about titles before mentioning it. Firstly, Euhpo was not based on manga, but on novels, and secondly, KyoAni rewrote scenes, but they didn’t rewrite the relationship between the characters.Secondly, there is no representation of LGBT in the show and Kumiko was never physically attracted to Reina. As in the original novel, Takeda uses the popular Japanese motive of admiring one girl for another, and also uses Class S elements to build a shinyu connection between them. Their relationship is not a love story and was not a rewriting, so, please do not write about it if you do not know the Japanese cultural context and the franchise itself.

You clearly care a lot about this series, John, so I commend your passion for it. The anime’s portrayal of Kumiko’s relationship with Shuichi is drastically different than how it was written in the original. The choice to eliminate evidence of her attraction for him, with more emphasis made on Kumiko’s attraction to Reina and even Asuka (whether it be “shinyu” or not) can be seen as queer. Who is to say that these Japanese cultural phenomenons are not queer? Or that queer individuals do not experience them?

Regardless, I wrote one whole sentence about this series in my article and you felt the need to flaunt your arrogance just to have the gratification of being “right” on the internet. I feel that you could stand to work on your critical thinking, John, and hopefully you will come to learn that your perspective is not the only one in the universe.

No, they were not qeer and the director directly denied this interpretation. If you like to believe that girls do not have to form other connections than physical attraction, your right, but in fact Yamada simply decided that romance would distract from the theme of eternal friendship, so she shifted the emphasis in the anime. She did it even in the officially heterosexual Koe no Katachi, which in the original was a romantic drama, by the way.

Oh, how familiar this behavior is to me – I have nothing to answer your words, so I will accuse you of arrogance and selfishness. Maybe you will not attack me instead of discussing my arguments? Thank.

Lets not forget how the west influenced the east in attitudes towards gay people, ancient japan is rife with art representing different sexualities, literature and art show that the attitudes held then were more open and positive.

the attitudes you see now, and are a result of western religious values being imposed through colonisation and exposure from the 1700s.

But that’s besides the point, interesting article but I should mention that as someone who has watched and read thousands of anime and manga i have noticed a shift in how gay people are represented, especially in Yaoi and Shonen ai ( which typically fetishize gay characters to appeal to women), there are hundreds of new manga depicting positive gay relationships with romance or without romance, it varies from adult gay men to teenagers coming to terms with their sexuality, there is often a true representation of how society deals with them and sometimes a hopeful look to the future. but I would caution you not to expect lgbqt representation to be similar to the west, because gay people are not all the same, and maybe you liked no6 because that relationship closely resembled how a western relationship should be, (more explicitly stated) but japanese culture is different and the headway’s being made should not be dismissed as not good enough for western audiences.

Excellent points, zin! I do mention the West’s influence on Japan’s views of homosexuality and queer existence — so I assure you, I did not forget.

You’re right that the anime and manga realms are shifting to more positivity, though more work still needs to be done (as is the case with many medias).

I am fairly well aware of the differences between queerness in the US, where I am, as opposed to in Japan, which I felt were addressed in the article. It’s a great topic to unpack: the expectations we have from a different culture when looking on from our own. However, I did not feel I dismissed the headway being made in the anime and manga industry, in fact, I felt the takeway here was uplifting and hopeful for LGBT+ representation. I certainly hope perhaps with a closer read, it would be clear that I am not dismissing progress, I am celebrating it and merely challenging the industry to keep improving.

Thanks for this article, I’ve only come across it a lot later than it was published, but it was well written and a great read. It’s always interesting to hear another’s perspective.

If you’re still following comments here, I would be interested to know your perspective on the recently aired “Banana Fish”. This was a 24 episode modern adaptation of a shoujo manga written back in the 80s, which I understand had quite a big impact back then. It tells the story of new York Street gangs, the Mafia, and drugs created for war by a corrupt American government, but the most important part of the story is the unlabelled, yet profoundly strong bond between the two main male characters.

Yet I’m hesitant as to whether it should be appreciated as representation, or seen as a story written for the satisfaction only of a heterosexual audience. The life story of the main character deals with very heavy themes such as rape, child prostitution, and more – is this telling the harsh story of what is a real problem, or going too heavy handed into the realm of intense sexualising? My final opinion was that it dealt with these themes respectfully, but at times went a bit too far for my liking, and that being a modern adaptation, the bond between the two main characters could have been explored explicitly in the dialogue with stronger words than the old cop out, “very good friends”.

Aside from all of this, the story overall was very good and I found myself captivated by the plot itself.

I would be very interested to hear your opinion and perspective on the series, if you are familiar with it. Thanks for the article!

Thank you for your comment, Raevenn!

Interestingly enough, I published this article about two months before the reboot Banana Fish series aired last year. I did watch it in full and I wish I could have included a point about the series in this article, especially since I discovered later that the Banana Fish manga was an influence for No.6.

I agree with your analysis of Banana Fish, and mine is very similar. I feel the 2018 reboot of Banana Fish is in the same realm of representation as Yuri!!! on Ice, as in, the MLM relationship is written mostly as a queerbait and as you say, can be read as “very good friends” because the creator(s) refuse to allow explicitly authentic romance play out on screen. However, that is not to deter anyone from reading the relationship between Ash and Eiji as romantic, nor to deter anyone from feeling represented by them or any other queer-coded characters in the series. Those readings of the series are all fine, but I urge fans to look critically at it, as well.

As for the genre and dark topics of Banana Fish, I agree that it can be taken too far at times and is definitely not something I would recommend to everyone. The plot and structure of the narrative itself is very strong. It is good to see topics such as rape, trauma, PTSD, and a corrupt government dealt with in a mostly respectful way, but the tragic ending of the series (and even more so in the manga) spell out a very bleak message for queer identifying folks. Because of the ending of this series and the constant trauma inflicted on a queer-coded character (similar to what occurs in Revolutionary Girl Utena to Anthy), I do not find the series very positive in its representations of queerness.

Finally, not to repeat what was already said in the article, but anime fans looking for an explicitly queer relationship in a series with dark/adult themes handled respectfully may wish to try No.6 before braving Banana Fish territory.

Everyone needs to read Shimanami Tasogare. It’s a great story with genderqueer, gay, asexual, and lesbian characters with a happy ending. Plus the art is simply stunning.

Mitsurugi Hanagata

is a great representative anime character for a queer

this was an interesting read O: i do think its worth mentioning more of the 80s-90s era though; sailor moon and utena are both commonly talked abt whem discussing queer rep in anime/manga but theres a lot of similar m/m from that period that barely anyone knows of much less brings up for rep (which id like to research more at some point tbh bc its kinda intriguing). stuff like terra e (takemiya keiko), which has actually no explicitly romantic relationships- het or homo- aside from side m/f pair who are fed to the plot, but the manga (1978 iirc) has jomy, the male protag, chasing his (deceased, male) mentors shadow for basically the whole plot. the anime (2007) lets said mentor live a bit longer so the plot changes, but not jomys obsession with blue. takemiya also wrote kaze to ki no uta (gay romance) prior to TE and its often mentioned in the same breath as rose of versailles (riyoko ikeda, queer romance, wlw or transmasc/cis girl depends on how you view oscar), etc. theres also clamp as you mentioned, with tokyo babylon being standout (as its definitely gay but definitely not a romance; clamp also has at least one lgbt element per series), ooku (really intriguing gender role.. study, i suppose), antique bakery (100% gay, 100% realistic) and so on. im not sure if im coming across coherently oops//

i just find it rly interesting how the 80s-90s, 70s even actually had a lot of queer rep in what was more or less popular at the time (mostly in the shoujou genre & by female authors), but moving from late 90s to 2000s, and only recently non Yaoi tm lgbt rep is starting to come back. but the point im trying to say is it was there, and it was really common- im just not sure what happened? could be relevant to jpn cultural values and growing western cultural exchange.. im not debating bc i dont have a point to stand on hahah but just food for thought O: