Inside America’s Fascination with Witches

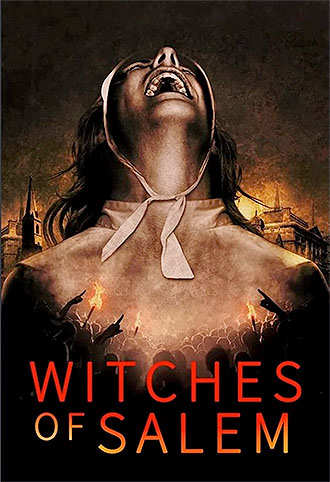

American culture has long nursed a fascination with witches and magic. This fascination has waxed and waned in 300-odd years, coming to the forefront more in some decades than others. In the 21st century though, witches, magic, and surrounding folklore are making an especially big comeback. In 2019, the four-part documentary miniseries Witches of Salem premiered. It’s now a popular streaming choice on Discovery Plus. Novels from The Hour of the Witch to the Brooklyn Brujas series, from Cemetery Boys to A Secret History of Witches, have flown into our bookstores in droves, roosting on tables of our most popular fiction. The 1993 Disney film Hocus Pocus has gained a vocal cult following in the 30 years since its release, inspiring everything from Hallmark ornaments to Starbucks drinks. Its fans now eagerly await the long-anticipated sequel, streaming on Disney+ September 30.

Yet what exactly has stoked America’s fascination with witches since the country’s inception, and especially in recent years? Why witches and not wizards? Why, for example, are witches still popular when franchises like Harry Potter star males? How and why has our culture evolved from seeing witches as Halloween denizens in black capes and striped socks, to seeing them as powerful, multi-dimensional women?

The answers are complex, as three-dimensional as real and fictional witches themselves. Many of these answers can be traced to women who were not actual witches, but suffered and died after being accused of witchcraft. More specifically, the answers can be traced all the way back to the Salem Witch Trials. The centuries-old trials are inextricably tied to modern culture’s fascination with witches. When we uncover their secrets, we can uncover how culture not only interacts with witches, but how we will interact with them in the future.

For the purpose of our discussion, a “witch” is always female, real or fictional. She practices some form of magic, whether that’s fairy tale magic, folk magic tied to a specific culture, or “traditional witchcraft” tied to a specific religion such as Wicca or paganism. Alternatively, she is accused of practicing one of these types, or is suspected of practicing witchcraft because she engages in certain behaviors or has certain distinguishing habits or features. She may work alone or have a coven or family with her (e.g., the Sanderson sisters). She may use her powers for good or evil, but because of the connotation of “witch,” may often be suspected, accused, or convicted of evil intent.

Secrets of the Salem Witch Trials

Historical and Cultural Context

Witches, or versions of them, existed long before America’s inception, or even America’s birth as 13 original colonies. Historians don’t know when the first witches walked the Earth, but plenty of accounts exist in ancient holy texts like the Bible. The Bible tells its followers, “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live” (Ex. 22:18 KJV). It goes on to say, “Do not turn to mediums or seek out spiritists, for you will be defiled by them. I am the LORD your God” (Lev. 19:31). In the same book, God sternly warns His people, “I will set my face against anyone who turns to mediums and spiritists…and I will cut them off from their people” (Lev. 20:6). Through His prophets, God says he “will destroy witchcraft” (Micah 5:10-12). Several New Testament books, including Galatians and Revelation, list witchcraft as one of many sins for which the unrepentant will forfeit Heaven. Acts 8 records St. Paul’s confrontation with a recently converted sorcerer named Simon Magus, and Acts 19 records many new Christians who had practiced sorcery and witchcraft burning 50,000 drachmas’ worth of magic scrolls and books. In today’s terms, that’s 50,000 days’ worth of wages, or 136 years’ worth.

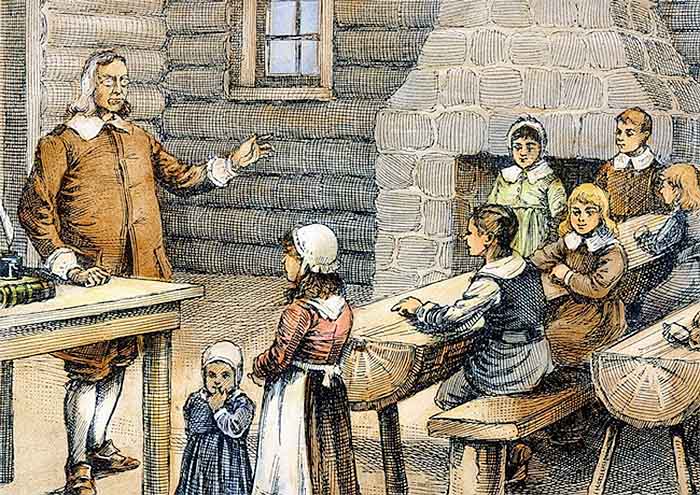

The Puritan citizens of Salem, Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1692, would’ve known at least some of this Scripture depending on one’s literacy level. Having fled England and its Church for relief from religious persecution, these devout founders of “a religious reform movement” would have held all of Scripture close to their hearts. But considering Puritans felt the Church should “eliminate all ceremonies and practices not rooted in the Bible,” and that they “had a direct covenant with God to enact these reforms,” they would have looked with special suspicion on supposed witches. Membership in the Puritan church and community of Massachusetts Bay Colony was “restricted to full church members [or] ‘saints,'” and any who violated Scripture as the Puritans interpreted it, was in danger of excommunication at best and hellfire at worst.

Puritans take center stage in American history around 1689. That year, King William’s War “ravaged regions of upstate New York, Nova Scotia, and Quebec…sending refugees…[specifically to] Salem Village in the Massachusetts Bay Colony” The area encompassed both Salem Village, which is now Danvers, MA, and Salem Town, which is today’s Salem, MA proper.

Salem’s resources were quickly strained to the breaking point. A total lack of modern medicine and sanitation touched off a smallpox epidemic, which decimated the population and “heightened witchcraft suspicions…launching grudges that could last for decades.” Smallpox was particularly tied to witchcraft because many victims suffered from permanent scarring and blindness, both of which were associated with witchcraft outside of disease.

By the 1690s then, Salem was ripe for a crisis. The arrival of new minister Samuel Parris gave it to them, as his “hellfire and brimstone” sermons fed the existent paranoia, especially in Salem Village (Witches of Salem Episode 1). Parris was not necessarily a well-respected minister, but he did tell his parishioners what they wanted and arguably needed to hear. He blamed all of Salem’s recent troubles on the devil, the most common and logical adversary for Puritans. According to historians, “Puritans didn’t believe in coincidences or accidents” (Ep 3). Therefore, tragedies such as epidemics, attacks from “the natives,” and war-related fallout, had to be the direct work of Satan (Ep 1). Since Satan was not easily found and impossible to prosecute, the next logical step would be to find and prosecute his followers–namely, suspected witches.

Do not assume, however, that witches simply appeared out of nowhere in Salem. The Puritan culture, along with the historical context, provided a “perfect storm” for a witch hunt. Puritan culture was heavy on hard labor and dour self-reflection; “light and joy” were almost nonexistent, especially in houses like Samuel Parris’ (Ep 1). The one day of rest, Sunday, was no day of rest at all. It was instead devoted to 8 hours of worship, at which anyone who did not pay strict attention was reprimanded and subtly shamed (Ep 1). After an 8-hour church service, families would return home only to read and analyze Scripture for the rest of the day. Little to no entertainment or recreation existed, so Puritans, particularly children and adolescents, would make up their own.

The Travel Channel documentary Witches of Salem, which draws heavily on actual transcripts from the Salem Witch Trials, tells us some Puritans found entertainment in “folk magic” (Ep 1). For instance, it’s said that Samuel Parris’ nine-year-old daughter Betty and his eleven-year-old niece and maid, Abigail Williams, tried to divine the names of their future husbands using a Venus glass. Supposedly, an egg white placed just so into a Venus glass would coalesce into the name of a girl’s future mate. But when Betty and Abigail looked in, the white coalesced into a coffin shape (Ep 1). Historians note that, “In an environment where they had been taught that dabbling in any kind of witchcraft was…inviting the devil into your soul…[the girls] would have been terrified” (Ep 1).

Puritan culture did make some distinction between “folk magic” and actual witchcraft. Folk magic is nebulous, in that it is meant to protect its user from the evils of the actual craft. For example, an herbalist healer might be said to use folk magic in her cures for common illnesses. However, Puritans acknowledged there was a “very fine line” between folk magic and evil witchcraft, and they couldn’t necessarily gauge where that line was (Ep 1). That fine line “becomes the crux of the problem” as the witch hunt takes off in January 1692 (Ep 1). For the next eight months, Salem Village and Salem Town would become a microcosm for hell itself, as an entire community wrestled with where the truth hid among loads of conflicting testimonies and questionable evidence.

Afflictions and Accusations

After the Venus glass incident, Betty and Abigail begin experiencing “violent fits” (Witches of Salem). In 1692, “fits” were another word for “seizures,” which were the most common manifestation of what were eventually called “afflictions.” Along with those, Abigail was said to “[talk] in a disconnected way,” and Betty was observed “crawling under chairs” (Ep 1). Over time, more girls, such as “Ann Putnam Jr”, also known as Annie in some accounts, and the Putnam’s servant Mercy Lewis, experienced symptoms (Ep 2). Again, seizures were the most common symptom, but Ann Putnam Jr. claimed suspected witch Martha Corey struck her blind at one point, and Mercy Lewis claimed a “specter” bit her on the arm, leaving marks (Ep 2).

The explanations 21st-century historians or laypersons might come up with, such as adolescent girls acting silly, self-harm, or physical illness, barely occurred to Puritan Salem. To their credit, Samuel Parris, Thomas Putnam, and others did call in local physician William Graves to determine if the “afflictions” had physical roots. But as a Puritan himself, steeped in a culture where the strange and unusual was attributed to God or the devil, Graves found nothing. He instead advised prayer and fasting for the afflicted girls’ families, and when the afflictions continued, the finger was pointed at witchcraft (Ep 1).

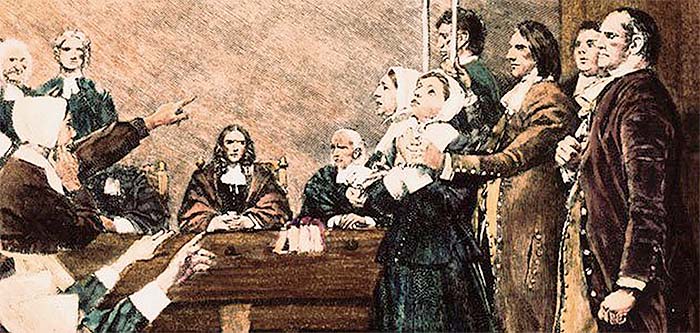

In the eight months of the Salem Witch Trials, an increasing number of afflicted girls came forward, accusing various community members. Most of their names are not known, but several remain entrenched in history: Betty Parris, Abigail Williams, Mary Walcott, Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, and Mary Warren (Witches of Salem). At first, the girls tended to accuse the same people of witchcraft. The first three “suspects,” Sarah Good, Sarah Osbourne, and Tituba, the Barbados-born house slave of Samuel Parris, are perhaps the best known. All three were outcasts; Tituba, a non-white slave, Sarah Good, a beggar, and Sarah Osbourne a “quarrelsome” woman with “a slippery tongue (Ep 1). They were “stereotypical,” “straight out of central casting for witchcraft” (Ep 1). But over time, the girls began accusing prominent and trusted community members, from Martha Corey to Rebecca Nurse. The latter was known for her piety, no easy feat among Puritans.

Historians describe the accusation of Rebecca Nurse in spring 1692 as “a critical turning point” in the Witch Trials (Ep 2). They observe, “It’s one thing to go after outliers,” acknowledging Puritan culture’s insular, rigid nature (Ep 2). But accusing someone like Rebecca Nurse adds a new dimension to the trials, and to the fascination modern observers have with both the historical event and witches, real or fictional.

Afflictions of Mind and Heart

The “critical turning point” raises the question of what truly motivated the afflicted girls. Many laypersons, such as Crucible playwright Arthur Miller, imply they acted from pure spite, seeking to simultaneously punish their community’s outcasts and rid themselves of voices who might have the power to question their behavior. Others, such as Ann Rinaldi, author of young adult novel A Break With Charity, chalk the Witch Trials’ impetus up to chronic boredom, peer pressure, and social tension. But a close look at the accusers and accused reveal motives much deeper than meanness, cries for attention born of boredom, or peer pressure. The actual, layered motives play into how we interact with witchery today.

Historians who worked on Witches of Salem admit “peer influence is everything for adolescents and teens,” and that the “circus-like” atmosphere of the Witch Trials gave the girls more than enough reason to “perform their afflictions” (Ep 2). In fact, since the girls were always present during an accused witch’s “examination,” spectators likely expected such performances. Yet, the word “performance” isn’t synonymous with “fake.” Historians tell us these girls could have “reveled in their newfound power” and sincerely believed they were bewitched (Ep 1). Every adult they trust has taught them witchcraft is real; the “greatest minds of the age” believe in witchcraft, including ministers, professors, and lawyers (Ep 2).

Couple this with the “anxiety and chaos” of the court, and the girls may have caved to pressure to act out afflictions they didn’t feel (Ep 1). They may have sincerely believed people like Tituba or Sarah Good were dangerous, and were probably “legitimately afraid of the women they were accusing,” having been taught a witch’s dark magic could turn on an accuser (Ep 1). The eventual hysteria that ensued as more girls came forward would have fed into the initial fear and the pressure of the tense, “circus-like” court atmosphere. Indeed, historians in Witches of Salem call the initial trials “a lid on a pressure cooker, ready to explode” (Ep 2).

For some of the girls, yet another layer existed. This layer relates to the “boredom” theory, but is far deeper and more insidious. Episode 2 of Witches of Salem tells us Abigail Williams, in particular, spoke out in church as evidence of her affliction. She began mimicking Parris during his sermon, mocking his text choice, rolling her eyes, and saying things like, “That’s enough of that!” Today, we’d consider this a stifled, perhaps anxiety-ridden kid acting up in church. But in 1692 Salem, Abigail was “out of bounds of proper behavior,” which was considered “devilish” (Ep 2). Perhaps then, Abigail and others sought release. As misguided as they were, perhaps they were also desperate enough to hurt others because their culture had hurt them. Thus, the girls may have continued acting afflicted because the witchcraft story provided an alibi and a way to maintain what little respect they had in the community.

No matter an individual’s opinion on the afflicted girls–and most opinions are not favorable–they win sympathy through this lens. The girls and the hysteria they wrought in Salem become chillingly relatable. Part of our fascination with witches lies with those who “cry witch.” Most of us would not touch off a “witch hunt” to deal with people we feared or disliked. Yet, most of us have felt oppressed or suppressed at some time. Most of us have looked at a situation, either in our lives or farther afield, such as in the news, and asked ourselves, “How did we get here? How did this ‘little’ problem get so out of control?” We have fought against fear. We have been the voices to whom the majority would not listen. In our worst moments, we have used spiteful or misguided methods to make ourselves heard. Perhaps most of all, we have watched others accused or treated as outcasts, as the accused witches were. We have either feared becoming one of them, or lived that experience.

The Specter of False Evidence

Once we understand those who “cry witch,” our curiosity and fascination turns to the “witches” themselves. It’s easy to think of women like Tituba, the Sarahs Good and Osbourne, Martha Corey, Bridget Bishop, and others as victims. Certainly, they were, in many ways. Yet they were some of the most memorable and strongest victims in history, with much to teach modern history students of any time period, age, religion, or ethnic group.

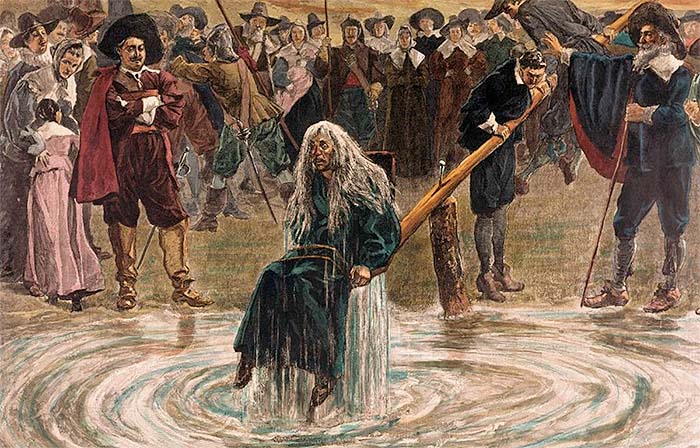

The scariest “secret” of the Salem Witch Trials is the fact that they were not “trials” in the strictest sense. They were hardly legal proceedings at all. Remember, the United States of America did not exist at the time. What we know as Massachusetts was still a colony under English rule. While the colony was due to receive a self-governing charter, it had not arrived by April 1692 (Ep 3). Governor William Phipps was obliged to create an “emergency court,” having arrived in Salem from England to discover Boston Jail filled with 150 suspected witches (Ep 3). These “witches”–mostly women, though by now a few men, such as former minister George Burroughs, had been accused–were “languishing” in a man-made hell of “rats…unwashed bodies…and…rotting food on the floor” (Ep 2). Worse, not only were these “witches” denied real legal proceedings of any kind, but they had been “convicted” based entirely on something called “spectral evidence” (America’s Hidden Stories, “Salem’s Secrets.”)

“Spectral evidence” is defined as “a witness testimony that the accused person’s spirit or spectral shape appeared to him/her in a dream” (salemwitchmuseum.com). A “spectral shape” might be a person’s body double, such as when Abigail Williams accused Martha Corey of afflicting her while sitting atop a church beam, although Martha was in a pew at the time (Witches of Salem Episode 2). It could also be an animal or “witch’s familiar” (Ep 3). Throughout the Witches of Salem documentary, the devil’s yellow bird or the yellow bird of witchcraft is mentioned as spectral evidence. Additionally, a specter could be invisible, or afflicting someone from afar–i.e., afflicting a witness in church while the person herself remained in her home. Thus, the accused witches were often said to touch or bite their victims. According to Witches of Salem, Abigail Williams accused Rebecca Nurse of making her hand burst into flame, although no fire was visible (Ep 2).

Spectral evidence then, was impossible to disprove, even if other witnesses contradicted it. For example, early on in the trials, Tituba confessed to witchcraft and being in league with the devil. Seeing that denial of witchcraft hadn’t helped her fellow accused, the two Sarahs, she “gave the court what they wanted to hear,” and then claimed the two Sarahs were afflicting her (Ep 1). But considering that in Salem, the best proof of witchcraft was the testimony of another confessed witch, the use of spectral evidence meant the witch hunt might never end. If anything, “any name at all might be shrieked in the parsonage” (Ep 2).

Again, an almost macabre intrigue comes into play for modern witch aficionados. The modern American court system doesn’t use “spectral evidence,” but the existence of organizations like the Innocence Project proves evidence is planted or tampered with all the time. The fact that in Salem, witchcraft was “a crime of revenge,” often based on malicious gossip or intentions, reminds modern Americans how easily someone’s life could be ruined based on an old misunderstanding or grudge (Ep 3). In fact, one need not face criminal accusations to identify with Salem’s “witches.” Anyone who has faced bullying in school or the workplace can testify to the lasting trauma connected to vengeance, maliciousness, and the relentless speed of the rumor mill. Anyone who has faced betrayal from a family member, close friend, or member of a religious “family,” can testify to how quickly familial affection might become paranoia or hatred. In any or all these situations, “innocent until proven guilty” becomes a foreign concept. The reverse is true, which leads to the final and most intriguing secret of the Salem Witch Trials.

Earth-Shattering Role Reversals

The most relatable and frightening aspect of the Salem Witch Trials lies in how they turned an entire community and culture upside down. Once the adolescent “victims” began reporting afflictions, an almost total role reversal took place. The accusers, young girls, were “predominantly the least trusted members of the community,” yet they “[trumped] the word of the most trusted members” (Ep 2). For instance, Rebecca Nurse, one of the most pious and trusted members of Salem who “loomed large in the imagination” as a “true Puritan saint,” reached out to the girls and urged them to speak the truth (Ep 2). Mary Sibley, who used folk magic but was considered “devout,” tried to help the girls as well (Ep 1). But respected, learned men such as Minister Cotton Mather had written books about successfully treating young women for witchcraft (Ep 2). Additionally, young women were considered “particularly vulnerable to Satan’s influence” (Ep 2). And although not all suspected “witches” were stereotypical in their presentation, many were, or “misbehaved” enough to raise eyebrows. Therefore, the role reversal not only stood, but ran deeper into Salem’s culture with each trial, accusation, and dramatic “performance” of “fits.”

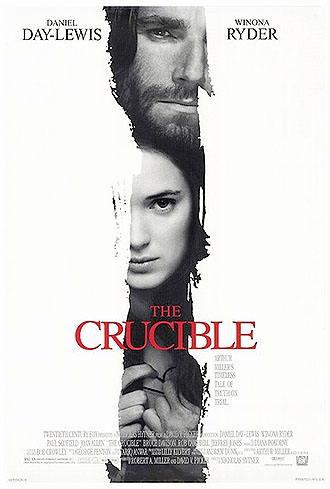

We find another role reversal in exactly who gets the blame for Salem’s “witchcraft” outbreak. Throughout the Trials the afflicted girls, and later afflicted adults, have blamed the devil for giving the suspected witches power. The 1996 film The Crucible shows ringleader Abigail Williams and her friends crying out they saw every suspect with the devil. This checks out, since “in the patriarchal Puritan imagination, there must be a man behind all this manifestation of evil” (Witches of Salem Episode 3). Indeed, George Burroughs is eventually hanged as the devil’s agent, the “man in black” (Ep 2 & 3).

However, we cannot forget the majority of accused witches were women. Ideally, a patriarchal society such as Salem’s would’ve taken the Bible’s admonition for women to be “loved as Christ loved the church” seriously (Ephesians 5:25). It would have afforded women protection, unconditional love from husbands and male relatives, and elevated status. But within the Witch Trials, we see a patriarchal society acknowledging that Satan–a male–is to blame for evil, while simultaneously punishing his supposed female followers, even if a male “agent” has been singled out. We see a society that claims the Bible as the final authority, going completely against its teachings on women, singling out females as particularly “devilish,” easily influenced, and dangerous. At one time, Salem held up at least some of its women, such as Rebecca Nurse, as “true saints.” During the witch hunt, these same women become symbols of great and contagious evil.

The final and worst role reversal in the Salem Witch Trials is the one that feeds our fascination with witches the most. It’s the least obvious, because it arches over every individual trial and every key player, accuser and accused. This reversal is the one concerning order and chaos. Recall, Puritan society was one of strict, legalistic order. In 1692, Puritans held order in a vise grip, controlling every iota of each other’s lives through work, religion, and high expectations. They had lived through such chaos and trauma, such a dramatic “pendulum swing” was a logical conclusion. Yet no one anticipated that a witch hunt, meant to preserve God and the church, would lead to the “anxiety and chaos” Puritan Salem fought so hard to avoid.

Such a tight hold on order and such a fear of chaos meant that when the slightest change upset the order, Puritans couldn’t cope. We as modern observers might scoff, but we’d do well to look in the mirror before laughing too hard. No matter who we are, we have all experienced some form of chaos, and we have all sought a “witch” figure to blame. That could be a person, a situation (which contains a person or group at the center) or even God (Who is a Being capable of human form). Alternatively, we may have been the “witch” others blamed for their chaos, anxiety, or fear. Indeed, we are capable of filling both roles, sometimes simultaneously. Even when we claim to be bystanders, we side with one faction or the other.

Knowing the Witch Trials’ “secrets” has led modern America down several paths. Some paths have tied directly into figuring the trials out, or preventing modern-day witch hunts, as Arthur Miller tried to do with The Crucible. Others have involved trying to bring justice to the victims, as seen in monuments and museums of modern-day Salem. The path we’re concerned with though, is how we have responded to the “witch” concept today, how the Witch Trials have shaped that response, and how we might improve in the future.

Creating the Modern-Day Witch

Armed with historical and psychological knowledge, Americans have sought to sate their “witch hunger” with new portrayals of these mysterious women (as well as warlocks and wizards, a witch’s male counterparts). Some portrayals are “wicked,” hearkening back to the suspicions hurled at women like Tituba, Bridget Bishop, or Sarah Osbourne. “Good witches,” on the other hand, seek to give witches a voice, and perhaps redeem their stories if not their histories from the atrocity that was Salem. Still other witches are neither wholly good nor wholly evil, but seek to humanize the moniker.

The third example, the humanized witch, is the most common today, and the one we need the most. To label a human with something like “witch” is to make her a “thing,” easily disposed of. But to humanize a label–to apply a name only after the person is fully known–grounds the name’s carrier in reality and respect. It gives outsiders a sense of how to interact and how to invite this new person into the wider world. It also gives the “witch,” the “outsider,” the choice to come into the wider world, leave it when she wants or needs, and come back at her leisure.

The humanized witches we’ll examine now are fully realized women. Some may lean farther toward “good” or “wicked,” but their motives are always clear. Each witch also carries a reminder of a Witch Trial secret, and her story shows us how we have chosen to deal with that secret, for good or ill.

Winnifred, Mary, and Sarah Sanderson

In the 21st century U.S., the word “witch” often conjures up memories of the Disney film Hocus Pocus, at least for millennials and increasing numbers of Generation Z. With a sequel on the horizon, the movie and its stars, the three Sanderson sisters, are more popular than ever. Played by Bette Midler (Winnie), Kathy Najimy (Mary) and Sarah Jessica Parker (Sarah), the “sisters” remain famous and respected almost 30 years after their 1993 premiere, despite a script many detractors call campy and lackluster.

The Sanderson sisters boast a direct connection to Salem. We meet them in 1693, after the Witch Trials proper. They’re residents of Salem but have managed to escape the hangman’s noose, until they’re caught trying to suck the life force from little Emily Binx. They’re hanged for their crimes, but not before turning Emily’s older brother into a black cat for eternity and pronouncing a curse that means they will resurrect centuries later. As promised, they return on Halloween night, 1993, determined to suck the life force from all Salem’s children to obtain eternal youth.

With this goal in mind, the Sandersons definitely lean “wicked.” Their individual personalities underscore this. Winnie is domineering and verbally abusive toward her sisters, manhandles and intimidates children, and says she has been to Hell and found it “quite lovely”. Mary sniffs and tracks children like a bloodhound, and relates to them primarily as food, such that her catchphrase is “I smell children”. And while Sarah comes off as ditzy and boy-crazy, viewers shouldn’t discount her desire to “barbecue and fillet” her male victims, or “hang [them] on a hook” to play with. In fact, coupled with Hocus Pocus’ odd focus on virginity, plenty of parents find voluptuous and sensual Sarah quite the problematic witch.

All this said though, the Sanderson sisters are easily recognized as human. When viewers see them cringing away from sunlight, they recognize their very real fear of death. Therefore, they see the sisters’ desire for eternal youth as relatable, if carried out in a selfish, wicked way. Viewers can also enjoy watching Mary and Sarah try to revel in Halloween festivities, despite Winnie’s protests and anger. They recognize these two sisters, at least, have been stifled and might seek constructive ways to experience the world. As for Winnie, she might have the same emotions. Perhaps she is simply a “tougher nut to crack.” The way she clings to her plan and her spell book lends credence to this theory. Winnie has learned to trust her powers over other people, including her sisters, therefore shutting out friendship and love. She calls herself her spell book’s “mommy,” indicating she has love to give and no constructive place to put it. The sequel adds flesh to this trait in particular, as we see a younger Winnie fleeing into the Salem woods alone to protect her sisters. Later, we see her ready to sacrifice her own life force to a real witch so Mary and Sarah will be spared.

The Sandersons’ encounter with Mother Witch, as she calls herself, hearkens back to the Witch Trial secret of prejudice and violence against women, as well as the role reversal of the patriarchal culture that failed to protect them. That is, the sequel shows us the Sanderson sisters were not “real” witches at first. They rebelled against Puritan conventions; Winnie in particular is anti-God and proud of it. They are accused of “unholy mischief,” and the town authorities plan to separate the sisters forever. But the sisters’ real motive involved staying together and expressing whatever differences they possessed in a safe place. Salem did not provide that safe place, especially for young women, but Mother Witch did. She tells Winnie “a witch is nothing without her coven,” and so the sisters become a coven of their own. The Sandersons seem to grow not only from witch power, but feminine power.

Witchy, feminine power, positively handled, redeems another Salem Witch Trials secret. Recall that many if not all the Trials’ female victims were accused of witchcraft in whole or in part because of how they “misbehaved” according to Puritan culture. Some of this “misbehavior” might’ve been legitimate witchcraft. For instance, Bridget Bishop possessed a collection of “poppets,” the Puritan equivalent of voodoo dolls (Witches of Salem Episode 3). But most of the “misbehavior” was tied to speculation and maliciousness. A Puritan minister who accused a “witch” of having a sour attitude or “slippery tongue” was likely guilty of the same sins, but conveniently forgot to examine his own soul.

Winnie, Sarah, and Mary Sanderson are accused of these same sins. Again, some accusations are rooted in truth. Winnie, whose relationship to God is the only one we know about, should arguably be aware that taking any deity’s name in vain might not be the best idea. And the Sanderson sisters are fond of using their tongues–and their spells–for vengeful purposes, which doesn’t help them or their victims. That being said, viewers can hardly blame the sisters, as they have been treated like outcasts practically their entire lives. Worse, those lives have been threatened based almost 100% on conjecture, fear, and superstition. Yes, the Sandersons do not accept Puritan culture, the Puritan God, or the Bible, but that’s their choice. The choice alone should not vilify them in the eyes of their community. The fact that it did, makes viewers cheer when they see the Sandersons choose feminine and sisterly power rather than the roles of victims.

Of course, this feminine power is problematic, for the sisters and their viewers. Feminine power, unchecked, leads to destruction just as masculine power does. Misused as it was in Salem and has been since, the Bible implies a balance is needed between masculine and feminine control (Ephesians 5). Other holy books, from the Torah to the Qran, as well as scholarly secular texts, indicate the same thing. Yet, whether in holy books, scholarly ones, or pure fiction, the allure of feminine power remains. The Sanderson sisters provide a cautionary tale to use it correctly, not to drain “life forces” in any context (e.g., mistreat others, sap others’ energy in a malicious way). Yet, their deep love for each other still comes through, and reminds us there is nothing wrong with women standing together to support each other. Their determination ensures they survive trauma many times over, and methods notwithstanding, thrive in a society that maligns their existence.

Galinda Arduenna Upland and Elphaba Thropp

Galinda and Elphaba first appeared in the 2003 Broadway musical Wicked, to the acclaim of audiences and critics alike. Played by Kristin Chenoweth and Idina Menzel respectively, the two first seemed locked into respective roles of completely good and completely wicked witch. Most Broadway audiences knew them from The Wizard of Oz, where they were stereotypical in presentation (pink, sparkles, extroversion, and kindness vs. green skin, black clothing, introversion, and coldness). But despite ending up in stereotypical roles, Galinda and Elphaba do more than most, if not all, witches in our discussion to redeem Witch Trial secrets and create the modern witch.

Wicked is very much a “how we got here” story, a “fractured fairy tale.” It takes a story audiences know inside out, The Wizard of Oz, and tells it almost backward, challenging audiences to rethink every inch of it. Almost from its first moment then, Wicked challenges audiences to rethink not only what they know about Galinda the Good Witch of the North and Elphaba the Wicked Witch of the West, but who these characters are. To wit, is Elphaba simply wicked because she was bullied at school, a loner, and an outcast? Was she wicked because her mother died when she was little and her father was largely absent? Perhaps, but this is a common backstory for many “wicked” characters, witches or not.

Similarly, maybe Galinda became “good” because she was always predisposed to “good” traits or had attentive parents. Maybe she was fortunate, materially and in terms of emotional development (a gift for making friends, a strong support system, listening ears should her mental or emotional health suffer). But again, these are easy answers. Wicked pushes the envelope for both characters, dismantling one of the core Salem Witch Trial secrets–the idea that to be a witch, a woman has to fit a stereotype. Sometimes she doesn’t, and the very fact that she doesn’t, can simultaneously put her in more danger and make her a stronger person more worthy of saving, support, and a place in her world.

Audiences see this play out as, in real time, Elphaba and Galinda change from stereotypes to fully realized young women. At first, they throw themselves into their “unadulterated loathing” of each other, with roles clearly defined (Wicked 2003 track 4). Galinda is the “martyr,” put upon by the “terror” that is Elphaba, while Elphaba has no one on her side, as everyone at Shiz is all too eager to tell her (track 4). Elphaba’s green skin, plus her allegedly antisocial attitude and bookish nature, isolate her from classmates who won’t engage with anyone different, while Galinda soaks up constant admiration. Said admiration isn’t entirely unmerited; Galinda is beautiful, social, and legitimately kind, at least to the degree she knows how to be. For instance, she recognizes Elphaba is quietly suffering at Shiz and needs help to make friends. But Galinda channels this into efforts to make Elphaba “Popular” (track 7). It’s only when she learns some painful lessons in true empathy that Galinda can understand Elphaba’s journey as a witch, and complete her own “witch journey.”

Galinda doesn’t come to this understanding until after her friendship with Elphaba (or Elphie, as she comes to call her) is tested in a “trial by fire.” Elphie stands up against the animal cruelty and Nazi-like discrimination taking place at Shiz and all over Oz, which spells doom for respected professor Dr. Dillamond and innocents such as a lion cub being imprisoned on school property. This gets her branded as evil, and she stands to lose everything, including her chance to develop her gift for sorcery with the Wizard of Oz himself. When the sheltered Galinda refuses to join Elphie’s cause and “defy gravity” with her, and when Elphie’s love interest Fiyero gets caught in the crossfire, Elphie feels she has no choice but to embrace her evil side. “Let all Oz be agreed, I’m wicked through and through,” she sings (track 16). She mourns her choices and plunges into some dark soul-searching, wondering, “Was I really seeking good, or just seeking attention?” Meanwhile, Galinda seems to have betrayed and abandoned her, siding with a band of witch hunters and giving in to the saccharine “good witch” stereotype the Wizard and the cutthroat Madame Morrible have pinned on her.

However, Elphie’s climactic dark moment pushes Galinda to a dark moment of her own. She, not Elphie, is eventually the one to expose the Wizard of Oz as the fraud and cruel dictator he is. Consequently, she’s able to convince Elphie to free Dorothy, who was falsely accused of killing Elphie’s sister Nessarose (known to audiences as the Witch of the East). Galinda doesn’t convince Elphie to become “good” again, and she does keep the “good” label for herself. But she also redefines “good” on her own terms, and redefines herself. For instance, she drops a syllable, becoming “Glinda the Good.” In the finale song “For Good,” Glinda acknowledges Elphie’s friendship and love changed her for the better, and that Elphie has done good things in her life. Elphie doesn’t deserve to go down in history as a wicked witch whom no one will mourn. On the other side of that coin, Glinda deserves to be more than a sweet, but arguably empty-headed “good witch” who literally floats through life in a bubble. The two became friends, reversed roles, smashed each other’s expectations, and reversed roles again. In so doing, they redeemed the kind of role reversals the Witch Trials pulled off, and expanded opportunities for the modern witch.

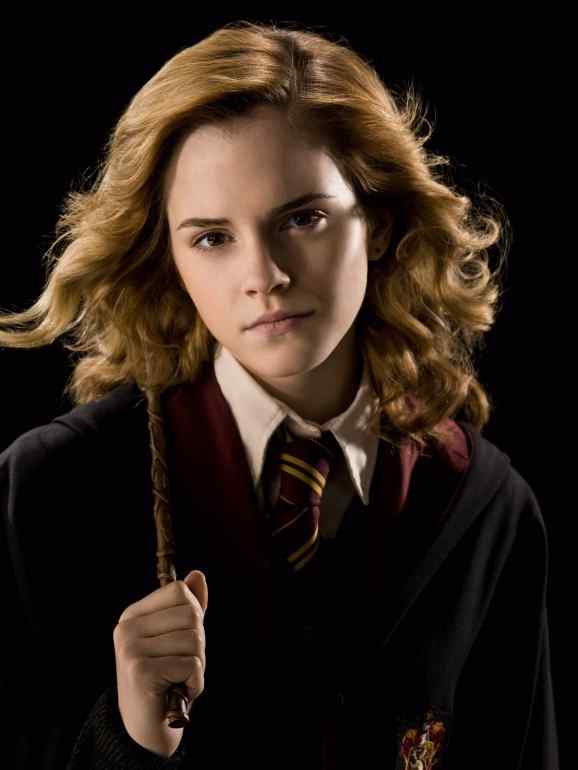

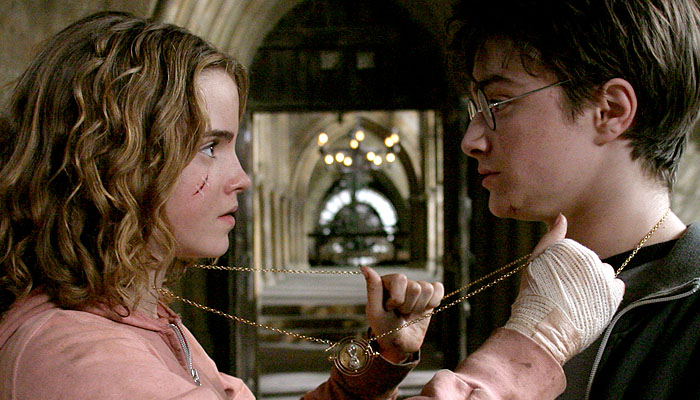

Hermione Granger

Hermione Granger came onto the “witch scene” in 1997 and has been a formidable presence ever since. She’s one of the first names readers or viewers think of when given the word “witch.” Although she’s a sidekick to franchise protagonist Harry Potter, she’s a powerful heroine in her own right, such that some readers still question why the series wasn’t centered on her. Hermione is one of the witch scene’s most enduring members, and arguably, she’s done more than any other fictional witch to dismantle the harm the Salem Witch Trials did when they cloaked the “witch” identity in fear and suspicion.

At first, Hermione looks like an unlikely candidate for this role. As noted, she’s a secondary character, not a featured protagonist. Plus, although she uses magic, she rarely if ever calls herself a “witch” in the Harry Potter series, nor does anyone else. In fact, “wizard” is used far more often than “witch,” often interchangeably, even though “witch” is supposed to be the Potterverse’s female designation. And although Hermione is “The Brightest Witch of Her Age,” magic is a matter of course for her. Unlike the Sanderson sisters, Glinda, or Elphie, she doesn’t treat is as a special gift or a creative pursuit in which she takes pleasure. She doesn’t use it for personal gain, whether that gain is beneficial or malevolent. Unlike the ladies of Salem, being “different” doesn’t seem like an integral part of Hermione’s identity, for good or ill. Rather, Hermione reads like any other gifted, hardworking student in Britain. She just happens to be studying charms, potions, and herbology instead of biology, chemistry, and math.

The truth is though, it is precisely Hermione’s normalcy, her acceptance of magic, that makes her the perfect witch to unmask Salem’s secrets and change the game for the modern witch. She’s a Muggle-born, someone with two non-magical parents, who didn’t know she was magical until she turned 11 and got her acceptance letter to Hogwarts. We don’t know if, like Harry Potter, Hermione ever experienced “accidental magic” (underage magic performed without foreknowledge or training, often in the presence of strong emotion). Thus, Hermione came to Hogwarts as a complete “blank slate.” She didn’t have any prejudices toward or against magic, as someone like Winnie Sanderson might have grown up with. Magic wasn’t a normal part of her world as in Elphie and Glinda’s, so she had no expectations of what was “good” or “evil” within it. Hermione couldn’t be shunned for magic because no one knew she possessed it. She didn’t have the benefit of a coven, but nor did she face the negative assumptions made about witches in other cultures or other universes.

This “blank slate” beginning frees Hermione up to determine what being a witch means for her, and how she’s going to use the power behind the name. In seven books and eight films, readers and viewers see her grow and develop more than we’ve seen any of our other witch characters do. Much of that development involves confronting the many facets of the witch identity and deciding how to integrate them into full personhood. For example, Hermione isn’t persecuted for being a witch at Hogwarts; she’s persecuted because she wasn’t born one. When Draco calls her a “mudblood” (read: dirty, corrupted, Muggle blood), Hermione is initially, understandably, hurt and demoralized. Like the ladies of Salem, she feels more like a thing than a person. She might even feel stereotyped, as readers see throughout the Harry Potter books that Muggles, even intelligent ones, are considered stupid because they lack magical acumen. But in an environment where the magical are the majority, and she has proven herself as one of them, Hermione has the security and confidence to reject those labels. She still acknowledges the unfairness and hurt, which probably plays a role in her “workaholic” tendencies. Yet in a “role reversal” of her own, she almost “reclaims” Mudblood as a badge of honor. When it’s tattooed on her arm as a symbol of torture in Deathly Hallows, Hermione keeps the mark in memory of her strength and survivor status.

Hermione also turns another Salem secret on its head by refusing to let “afflictions” of the mind and heart rule her. As a minority student, she has every reason to act like an Abigail Williams, Mercy Lewis, or Ann Putnam Jr. If not traumatized, at least in the early Harry Potter books, she has been severely culture shocked. She has gone from being one of her school’s top students who all her teachers probably loved, to a student some of her teachers ignore and call “an insufferable know-it-all” in front of everyone. She has stalwart friends in Harry and Ron, but still battles deep fear of failure and loss of acceptance in the wizarding world (we can infer the Muggle world at large hasn’t accepted her, so she would feel abandoned or “orphaned.”) At times, Hermione’s fears drive her so hard, she risks physically hurting herself, such as when she uses a barely-legal Time Turner to take every class possible in Prisoner of Azkaban.

With that track record, readers and viewers would hardly blame Hermione if she chose to shut herself off from the wizarding world, participating in class and not much else, or assuming most magic folk were prejudiced against her. Indeed, during Sorcerer’s Stone, this is basically what she does, to the point of almost being assaulted thanks to an escaped troll. Had Harry and Ron not been in the vicinity, Hermione could’ve been seriously injured or even killed. Like a Salem victim, she might’ve been considered deserving of such a fate, convicted in the court of public opinion. In the minds of some Hogwarts students, she probably was “convicted”; again, Hermione is mostly seen only with her two closest friends from this point forward. But because she chooses to stick with Harry and Ron after the troll incident and trust they are capable of showing true friendship, Hermione comes out better than a Salem victim. She unknowingly improves magical/Muggle relations, and sets the tone for those relations for the next several years, when they will be tested with Voldemort’s return and extremist policies.

What Does This Mean for Real Witches?

Witches as we have defined them here do not actually exist. In fact, modern Judeo-Christians, Muslims, and other religious and secular scholars are careful to delineate between these fictional witches, accused historical “witches,” and actual practitioners of the craft. Even practitioners delineate further, separating Wicca from witchcraft or “white” and “light” magic from “dark magic” or “dark arts.” Scholars like Dr. John Granger, who have examined the ongoing controversy between Christians and the Harry Potter series, endeavor to differentiate between “real” magic and fairy tale, fictional magic, or “incantational” vs. “invocational” magic. (Invocational refers to magic as work, as a living, whereas incantational refers to the conjuring of spirits, communication with the dead, and the like).

However, what does all this mean for the real witches walking around the United States of America today? Can and should fiction help “Muggles” relate to them? Should we try to relate to each other, especially if we have different religious or spiritual convictions? Is our fascination completely misplaced and morbid?

These are complex questions for anyone, but especially at this time of year, they insist on answers. They are questions this writer found herself eager to answer, as a devout Christian, a lover of justice, a lover of her femininity, and a passionate advocate of fiction and story. Her personal answers are likely different from those found here, but there are many answers anyone can embrace, backgrounds and beliefs aside.

Namely, the reality of witches, real and accused, in America cannot be ignored. The people who lost their lives to Salem’s hysteria deserve acknowledgment and as much justice as they can be given. For most of us, the best we can do on that score will be how well we represent witches in the stories we tell–as multifaceted humans who, if they do evil, do so with a good explanation if not excuse. If we actually know witches, we can extend this same grace to our interactions and conversations. Perhaps then our fascination can keep an appropriate measure of the mysterious when needed, but become a more integrated part of the overall story of American humanity.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Women accused of witchcraft continue to face persecution in Ghana, where they are sent to live in ‘witch camps’

Oh, dear. That’s terrible for them. I do want to research that topic now, though.

Wow 😳

The modern trendy witches are really boring. I like the tales of Baba Yaga in my childhood, a monstrous being who lives in a hut standing on a chicken leg and flies around on a broom. She is both good and bad, helps or eats people depending on her whim, very similar to the ghost and monster of the East.

Presumably Terry Pratchett based the character of the voodoo witch, Mrs Gogol, in Witches Abroad on Baba Yaga, at least to some extent. After all, she lives in a swamp in a floating hut that has very large duck’s feet so it can move around, and she is a not particularly good witch, although of course in the story, she is undoubtedly better than Lily Weatherwax.

Baba Yaga also appears in George R. R. Martin’s Wild Cards books. She is an ancient Russian crone who kills people by turning them into items of furniture.

There’s an interesting work by Robert Bly (Iron John) and Marion Woodman (Jungian analyst) who each write their take on the Baba Yaga story : The Maiden King. Worthy if a read imo.

I’ve heard of Baba Yaga, but didn’t know she had a good and bad incarnation. Thanks for the info!

Lots of contemporary authors grew up watching Buffy, Charmed et al. No wonder teenwitch fiction is growing.

Having been a member of some typical Wiccan covens run by priestesses I can only tell you that power goes to women’s heads as well, it’s not called ‘Bitchcraft’ for nothing.

It is good, harmless fun when it works though, the casting of spells is really just done for it’s sense of empowerment and the hope of controlling the negative stuff in life.

The idea of witchcraft whether practised by males or females is becoming sanitised and nuanced now, quite divorced from its traditional framework of conjuring up elemental powers, pacts with the devil and such to the malign or benign purposes of its practitioners. Something is imaginatively lost.

Interesting take. I’m about the furthest thing you’ll find from a witch, but as I hope you could tell, I respect them as people who deserve better than they often get. The “witch fiction” I have seen has been nuanced, in that I’ve seen several different personalities within it. But is it necessarily imaginative? No. For instance yeah, pacts with Satan and elemental powers? I’ve seen it a lot. I’d personally rather see witches from more diverse backgrounds, especially in terms of religion. Or, since I’m a brainy girl, maybe witches who draw their powers from literature, physics, what have you.

Kiki’s Delivery Service is the ultimate witch for me. 🙂

Salem wasn’t the only instance. In 1662 at Hartford Connecticut, 2 women and a man were hung on the testimony of a sick child. Mary Barnes was my ancestor and family history says she was added to the trial because her husband wanted to marry a younger woman in the community.

Interesting! I always like to learn more of the history behind this sort of thing, particularly from actual descendants.

It might be well to consider that there really were witches in 17th century England and New England, and that they did malevolent things to their neighbors. I don’t mean people with real supernatural powers. Think of voodooism in Haiti. If a person truly believes that a voodoo priest has cast a spell on him to sicken and die, he may very well do so. Belief is the key. If voodoo is effective in the present, think what witchcraft could do 300 years ago when everybody believed in it.

Yes, the power of belief is incredible. What disturbs me is how it can be turned toward evil as you said, or misused (e.g., fake faith healers, televangelists, that kind of thing). That also circles back to the question of, if a person truly believes in his or her religion, whether that’s voodoo or Christianity or something else, how can or do they separate the potentially evil parts from the healthy ones? What can people in religious communities do to stop religion from becoming evil, or what should they do if/when that line gets crossed? Or, are some religions/practices evil in themselves (I don’t know a lot about voodoo, so for instance, is there a complete voodoo practice wherein all intentions are malevolent)?

The phenomenon of witch trials has not really ended in the US — they still regularly occur just witches have been modernized and replaced by more current evil-doers.

I’ll amen that all day. The Red Scare, the Satanic Panic of the ’90s…and I got one more word for you. Coronavirus.

Good article for the Halloween week, The Artifice!

The events of 1692 have turned out to be quite a tourist cash cow for the town of Salem. However, many of those events actually took place in a separate community which is now called Danvers, but was known as “Salem Village” at the time. In the 19th century it was the home of Danvers State Hospital, one of Massachusett’s main mental institutions. Who says we don’t do irony?

Apparently it didn’t really feature in people’s awareness until after Arthur Miller’s play. He describes his visits to the area for research in Timebends, his autobiography.

You bet we do. I don’t live anywhere near the area, but I kinda feel bad for Salem and Danvers residents because it has become such a kitschy cash cow. If I ever visit, it will be for the serious history and to pay respect to innocent victims who could’ve had better lives. Now, I get it–some of the kitschy stuff is a way of striking back, and some of it can be fun, if you’re just a tourist looking for a unique way to kill a weekend. But as I said in the article, witches are so much more than the images we’ve cooked up over the centuries.

A personal favorite witch film is The Witches of Eastwick.

The Witches of Eastwick movie has dated terribly. It is a very 80s movie, reflecting the cultural mood of the time, with its weird feminism. In the 80s movies, successful and independent women were always shown to have something wrong with them, wrong with their soul, as if they were being too ambitious and needed a man (Mclane’s wife in Die hard). Men were also essential for women to get anywhere (Working Girl). At other times they were depicted as being vain and materialistic (for example Darryl Hannah’s character in Wall St). The feminism of 80s Hollywood was perverse because it was only limited to the imagery, kind of like saying, “well, this is the kind of modern woman around these days so we gotta show her” and then taking that opportunity to subtly bring her down a few pegs. Women centered movies showed them to be as powerful or glamorous as in Witches of Eastwick but behind the facade were deeply flawed humans who were vain, shallow and inferior to men. They were shown to have a superiority complex and they were represented in such a way as to make the audience feel that these female characters needed to be handled. Women who made their own choices had freedom to make those choices but often those choices made them lonelynor vulnerable.

Good comment, very perceptive.

You think McLane in die Hard was shown as having no flaws and didn’t need a woman? That was kinda the central plot line, he even narrates it to himself in the mirror for the hard of thinking.

Darryl Hannah was vain and materialistic in Wall St? Just like the men in the same movie? Almost as if it was commenting on Wall St culture rather than identity politics.

Yeah, I know in Die Hard that was the central plotline, but with whom is the audience supposed to feel sympathy? I am talking about female representation. John McLane is seen as the person who has suffered because of his wife’s choice to working independently. He gets his moment in the mirror but where is hia wife’s moment in the mirror? I mean, is the film sympathetic to Mclane’s wife? No. It is almost saying that neither of them would be in that situation if it weren’t for her ambition. She is clearly the unreasonable one, who is obsessed with her career and that has an impact on their marriage too. Poor hardworking guy who even saves her, is so misunderstood isn’t he? That is why the film is sexist because the film-makers intended to show that.

As for Darryl Hannah in Wall St, the difference is that men were always shown as being materialistic but when you have an independent woman like her character going for the same materialiatic things as the men, there is a difference. She is one of Sheen’s rewards, as fake as anything else he acquires & she represents something he gets with money. She is a trophy and a hollow one because being a modern, independent woman, she has no honourable ambitions, unlike Sheen who eventually changes. There is another guy who works with Sheen, the old guy who has had some bad luck in the stock exchange and he tries to advise Sheen about not being too ambitious early on, so that is another male character who recognises the downsides of being materialistic. It is a lesson Sheen learns in the film. The other women shown with Douglas are also depicted as being trophies or hangers on. There is no female character that has any redeeming feature. Even Douglas seems to have a moral compass of some kind (he kind of uses money as revenge for living in an unfair capitalist system). The independent and modern women are just after the money, and the riches and need men, with whom they only stock around until the going is good. Whichever you way you cut it, the film is not saying anything flattering about women.

So my favorite fictional witch is: Ischade

The whole archetype is fundamentally a product of misogyny and resistance against that. Arrogation by those with power of rights to heal or treat that we still see in various guises now.

No mention of Medea? Surely one of the first witches. Helping Jason steal the golden fleece from her own father, fleeing with him, then years later he abandons her for a newer model. Then she kills their many children. One version of it anyway. Like the The Life and Loves of a She-Devil. Echoing down, the woman scorned by the man. It’s a story as old as, well, as Medea.

Depends which version you read. Medea doing the killing is first introduced in the play by Euripides.

Before that the myth had them being killed by the citizens of Colchis as revenge for Medea killing their princess.

Great play though. Which is why it’s taken hold as the ‘authentic’ version.

The excellent re-make of ‘Suspiria’ embodies many of these themes too.

Fantastic article. Witches are wise woman and have a long history in the pre-Christian era. The evil witch is largely the invention of patriarchal monotheistic religions frightened of having their powers usurped. The wise woman was gradually villified to provide a convenient focus of hate, quite important in England after the Jewish community was expelled and we were short of scapegoats, inevitably culminating in persecution and murder as hate cults often do. Before the new religions siezed power, feminine power was strong and life giving. Erda the earth goddess and Isis are just two important goddesses. And let’s not forget Mary Magdalene, in early writings a disciple of Jesus but downgraded to sinful woman and prostitute by the time the medieval church got hold of the narrative.

Except England had one of least intense witchcrazes in Europe, other than during the dislocation of the Civil War, especially compared to Scotland but also to France, Germany and Switzerland. Shakespeare only wrote about witches to suck up to our new Scottish overlord, James VI & I. And in Europe generally at least a quarter and possibly two-fifths of executed witches were men.

See? You learn something new every day. Thanks.

Thanks for this. Also, thanks for the nod to Mary Magdalene. Jesus did indeed have devoted female disciples, and I don’t know how or why the Church got away from honoring them, or became afraid of them. Now, I don’t believe Jesus and Mary Magdalene were ever married, or hooked up, or anything like that. The Da Vinci Code and works like it are to me, blasphemous. But as far as vilifying women, yes, my faith is guilty of that and we need to do better. I will speak out until we do.

Another possible explanation for the current interest in witches is a degree of apprehension about how easy it’s become for witches (and wizards) to exercise their powers widely, and possibly recklessly, by posting online.

Fortunately, the risk of making a mistake in your incantation and hexing the wrong person is now greatly reduced by automatic spellcheckers.

On the downside, I would have thought it would lead more spells going wrong though or simply not working at all. I often have to make corrections where the spellchecker has changed a technical word it doesn’t know into a non-technical word from the approved list.

Some women claim to be witches to feel superior over others, women included. Get over it. You’re not a witch; they don’t exist any more than unicorns do.

Currently reading Wyrd Sisters for the first time – you wouldn’t mess with Granny Weatherax

Nor with Nanny Ogg.

Granny Weatherwax is my role model. One of my all time favourite literary creations. And one of the best depictions of a proper witch.

The depth of Pratchett’s folklore knowledge is remarkable – I’d love to know how deep he was into the ‘reality’ of the folklore he was drawing on and how much contact he had with practitioners. The Tiffany Aching books in particular are absolute mines.

Lords & Ladies will always be my favourite though.

I’ve always been intrigued by the notion of witches and I also have a soft spot for Wicca, even though I can’t take it particularly seriously due to its contrived origins (if you don’t believe me, read Ronald Hutton!).

A question for any witches reading this; do spells really work and if so can you prove it?.

Serious question really as if they do exist and do work, you can see why some people may not like it.

It’s a really good question. I don’t believe spells really work. I do believe in energies and intentions, if someone is thinking negatively about you I think it can affect you directly.

Maybe I should cut down on the smoke…

I like witches. They’ve had a bad press for centuries.

Think Buffy, and think the omnipresent Harry Potter world. A bit if mystery attracts us all – and of course – the obvious – the bleeding obvious – sex.

I could’ve devoted an entire article to all the HP witches–Hermione, Luna, McGonagall, even the lesser-known ones like Pomona Sprout and Lily Potter and the like. But I really wanted to bring in the Sanderson sisters, and focus on some other witches as well.

They’re fantasy figures, superheroines. Everyone wants to be someone else.

Witches have been a popular entertainment trope since forever. Although their currently popularity in this vapid TV format is more likely a result of people being dumbed down to the point where they believe in magic, they believe the earth is flat, they believe space doesn’t exist, they believe we live in a snowglobe, they believe there’s giants under Antarctica….I could go on.

As people abandon all hope of ever having a decent life thanks to the crushing disappointment that is modern capitalism, they will naturally seek refuge in escapist entertainment.

Thank-you for this article; it is a robust exploration of the Salem series and witches in general. I very much appreciate your take on all of this.

Great post. I recommend Hex by Thomas Olde Heuvelt. It is superb and as original a witchy novel as you could hope to find these days.

I think most girls go through a ‘witch’ obession/stage. I think a lot of it is because most girly things are not cool, but witches are; they’re powerful, can be frightening, can be ugly, and have a cool aesthetic.

One of the coolest shows from the 90s was Sabrina the Witch. It was a trippy show back then, but if your mind was in a certain place it seemed rational and Sabrina did get to be and do things you mentioned, but she was often put in a dilemma as to whose path/guidance to follow – laid back, caviler Aunt Hilda, or studious, stern Aunt Zelda.

The episodes when she was being mischievous and turn Libby into a donkey were great though.

Hmmm, interesting. I wasn’t allowed to go through a witch stage (Christian kid in the ’90s, need I say more)? Closest I got was more a “fantasy” stage (Narnia, Secret Garden, that kind of thing). But yeah, I was neither a tomboy nor a girly-girl, so maybe that’s why I explored that fantasy stage, and witches, more as a young adult.

These are fictional fantasy witches not true 17th Century Witches who were born out of poverty despair and ignorance and the human desire to blame somebody else for their misfortunes.

Totally agree. If you were not conforming to the ideal in the 17th century, you must be a witch.

I recently read the transcripts of 15th and 16th C witch investigations in Devon. Not a light subject by any means. We surely never want to return to that kind of imploded reality ? They say magic is the last bastion of power for the poor. However, i was struck that the internet and it’s various incarnations of hunts, trolls, horrors and laws is incredibly similar to the culture of the trials i was reading about.

The witch trails are a fine example of RELIGION run amok … When systems are dominated by a religious majority and or a religious Government we see time and time again ,,Logic and reason tossed out the window for a dark fantasyland that is far more lethal than ANY secularism .. This is why when the COnservative right crave more religion in American government it makes them appear like the people of Salem back in the day .. dim witted and narrow minded , with only power on their minds and very little room for Jesus

Oh, do not get me started… 🙂

These occult dramas are made to create an appetite for wireless/remote control technology in the same way Star Trek created an appetite for mobile phones.

Great article! I took a course during my undergrad that was about the History of Witches and the fascination we have with witches as American specifically is really interesting!

Jealous! Then again, if I had stuck around to take every cool course available in college, I’d have been crushed under the weight of student loans (not that they ever went away, heh, heh).

Witches are popular because they do spells and shit. And when you get fed up of em, you can burn them at the stake.

Always somebodies Grandma as well.

It’s a craving to go back to our pagan roots. Or it’s a feminist thing.

Maybe both? Or maybe a craving for God? (I’m a firm believer in Pascal’s assertion that there is a God-shaped vacuum in every human heart, so in every philosophy, I tend to ask myself, “Who are you trying to reach and how?” Pagan roots could certainly be your version of that).

Except before ‘pagan roots’ were created we weren’t pagan at all. We were probably many things, most of them unknown.

Wicca itself was the cultural invention of a 20th century Englishman. Before that it simply didn’t exist.

These things go in cycles and witches never fully went away. They were just eclipsed by vampires for a while thanks to Twilight and True Blood.

Why is witchcraft fascinating to people? Speaking as a Wiccan, because it is fun, hopeful, inspiring, empowering and a great way to mix with people.

Now, that’s interesting. I grew up hearing the exact opposite about Wicca, so what makes you use those adjectives, if you don’t mind my asking? (If you do, just ignore the question. Here to learn, not convert).

This was a good morning read, congrats Stephanie on such a detailed piece of writing. I’m big into folklore and after researching the ‘witch’ myself and in detail the Salam witch trials. It seems like the whole thing was just a way for people to gain power over another, with the church playing a huge role in segregation of communities. If you didn’t like your neighbour or your child was sick, blame the woman next door as she has a black cat or she looked at you funny. What fascinates me is the sexualised image of the witch — in Hollywood and other films. The Love Witch and other movies like Practical Magic and shows like Charmed all made being a witch look sexy and appealing. In comparison the Crone is haggard, ugly and always has saggy breasts. Of course this is not always the case. I grew up with Roald Dahl’s The Witches as a kid and that scared the hell out of me. I find the whole idea of the association between unconventional woman and the label ‘witch’ highly damaging and equally interesting. If you were into herbs and all that, lived alone, had pets for company and had a different way of thinking in regards to the ideals of your fellow women you were clearly a witch.

Oh, honey. By 17th century standards, I would definitely be a witch. Let’s see–voracious reader? Check. Likes cats? Check. Owns a cat (as much as a cat can be owned by a human)? Check. Has a different interpretation of the Bible than your average Puritan? Double check. Single? Check, check. Unconventional interests (e.g., Broadway, trivia, medicine, Irish culture, creative writing)? Hmmm, do they make nooses in size small? And can I get some emerald trim? Might as well go out in style!

It still resonates because New England – the nucleus from which the present United States grew – was set up in 1620 to create the Kingdom of God upon Earth in a virgin land. After two generations that project had evidently failed – New England had reproduced very much the same social ills as the Old one – so some supernatural explanation must be sought for its failure (…since by definition it couldn’t be that the idea was a flawed one to start with: God is perfect).

This is a theme which recurs throughout America’s history; the Promised Land, the City Set upon a Hill betrayed by its enemies both internal and external: the Tea Party movement runs on it. Paranoia and firearms were English Puritanism’s poisoned cradle-gifts to the state which it founded.

People were burning witches in the old country for centuries. Most of the witches were women.

Great article! I’m kicking myself for missing this around Halloween and only seeing it now.

Well, better late than never. Enjoy!

Great article – a wonderful morning read. Plus must say loved the new HP2 for some great witch positive perspectives.

As a Massachusetts native and a huge Crucible fan, super interesting article. It would be interesting to note the influence that Harry Potter has on all of this as a whole– I think it would be single-handedly responsible for a lot of this witch/wizard fascination.

The different approaches to witchcraft, the occult, and the supernatural as a whole is quite fascinating within academic discourses, both within sociology, history and other humanities sectors, but also in empirical ones. For example, parapsychology is the study of the supernatural and psychic occurrences, that is often viewed as pseudoscience, but can have some interesting applications. For instance, one article I read recently that was adjacent to the field mentioned how psychosocial and psychophysical coincidences and phenomena could be approached using ‘fractal thinking’, using the Mandelbrot set as a lens for understanding naturally occurring patterns within a seemingly chaotic environment.

I think its fascinating how america is often obsessed with things they deem to be unholy, they uplift and criticize in the same sentence.

I think the modern fascination witch witches and witchcraft is an attempt to dismantle longstanding patriarchal views about women being wicked, manipulative and vile. Embracing witchcraft is symbolic for embracing femininity and another way to take back control of women’s narratives.

The evolution of witches as a concept is reflective of the societal progression of women’s rights and freedoms, in a way.

During the Salem Witch Trials, women were targeted for being midwives, widows and spinsters – especially if they were unmarried and seen with men. It was thought that women not educated by the church having control over women’s sexuality and procreation were the work of the devil. It was just another way to instate the power of the Catholic Church and denounce women’s power.

The mockery of the witch figure, this time the one shown in children’s Halloween costumes and stories of the evil witch, is just an extension of these beliefs.

I believe the fascination with witchcraft in modern media is a new symbol of progression and women taking back their power. Although there is still some misrepresentation of the actual Pagan community, I think it is a good thing overall.

Women are seen as witches because they are independent — unfortunately, we have regressed once again to cheap horror movies featuring stereotyped women (Pearl is an example of that) and witches and this is just sad… Good is Kiki’s Delivery Service, an “old” feminist classic!

As a practicing witch, I find it so interesting how hollywood, despite being fascinated by witches, fetishizes witchcraft yet most of the time depicts withcraft so incorrectly. I love fantasy fiction, as well as most of the examples in this essay but I would also love to see a fairly well thought out film that actually depicts a close enough depiction of what a witchcraft, pagan, or wiccan practice actually is. The closest depictions I’ve seen are the Love Witch (2017) and Practical Magic, but I always find it fascinating and so frustrating that despite so much reference material and historical approaches, there aren’t many films that get it right.

However, I do find that all of these examples are great depictions for how the witch in media has become a feminist archetype, and how each of the examples of witches used in this essay have all used their own personal power to overcome being ostracized by their communities around them, in whatever way that is depicted. At its core, that is what I believe witchcraft to be and where the root of the fascination really lies. People, especially women want to see depictions of a women using their own personal power to overcome and defend themselves against a society that has wronged them or wrongfully accused them, because deep down, that is really how it feels to be a woman or femme in a patriarchal society.