Alexander Archipenko: Structure, Space & the Human Form

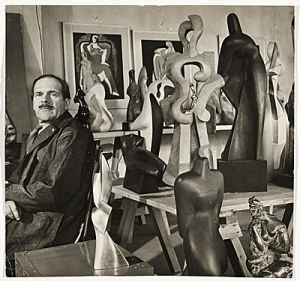

Ukrainian artist Alexander Archipenko (1887-1964) is most celebrated for his innovative representation of the human form through his distinctive sculptural style. Archipenko’s depiction of shape and space distinguished a new approach within the context of his artworks’ creation. His further radical innovations in use of materials and methods of construction also illustrate his key prominence to the establishment of new art processes and values. The sculptural works entitled Walking Woman (1913-1915) and Carrousel Pierrot (1913) display his abstraction of the human body to signify his pioneering approach of developing the conventions of modern art.

Archipenko left his native Kiev at the age of 20 and moved to Paris in 1908 during a remarkable period of art history, the beginnings of Cubism. Associated with renowned avant-garde artists of this era such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Amedeo Modigliani, Archipenko worked with these figures to help introduce and push the application of new concepts and techniques within the artistic movement. Archipenko explained, “I did not take from Cubism, but added to it.”

Archipenko left his native Kiev at the age of 20 and moved to Paris in 1908 during a remarkable period of art history, the beginnings of Cubism. Associated with renowned avant-garde artists of this era such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and Amedeo Modigliani, Archipenko worked with these figures to help introduce and push the application of new concepts and techniques within the artistic movement. Archipenko explained, “I did not take from Cubism, but added to it.”

Archipenko originated an innovation of the exploration of space and volume and its relationship to the human body. By 1912, the artist was contemplating the potential relationship between Cubism and sculpture. Archipenko sought to ‘reverse’ the conventional concept of a solid sculpture surrounded by space; introducing the radical idea of substituting human sculptural limbs with voids of free space. Archipenko centralised this theme frequently throughout his entire body of work over his art career. Furthermore, Archipenko often repeated his themes. He did this to have a continual conceptual focus in the deeper exploration of the human form as a symbol of structural Cubist undertones. Particularly, the characteristic play on concave and convex shapes in his human sculptures personified Archipenko’s interest in representing the human body with rhythmic movement and abstraction.

Archipenko questioned the established understanding of sculptural norms. Before his artistic debut, the art scene was generally monochromatic in terms of materials used and art making processes. He experimented with traditional, unusual and mundane materials – terracotta, bronze, wood, plastic, plaster, marble, bakelite, formica, glass and wire. His methods of construction didn’t involve expected processes of carving or modeling however nailing, tying and pasting. Archipenko created his works seemingly untidily to his fellow artists, wanting the junctures, nails and seams of his work to be emphasised and become unique details of the work itself. Archipenko also coined the term ‘sculpto-painting’ in reference to his sculptures’ vital combination of the sculpture/painting disciplines; a radical art making process of his era.

Archipenko branched out from past art movements, however, never sought to involve or allow influence from the pre- or post-war American society. This was despite Archipenko being an American citizen as early as 1928. His works therefore display a timelessness that is to be commended. The negativity, oppression and communism of the world around him did not affect or degrade the vivacity of his work. However, the relatable form and representation of the human body marked an identity and sense of connection to his work’s audience, time and place of creation. His individualism of artistic expression may have been seen to distance himself from his world of context but nonetheless allowed his artworks to respond and mark their relationship to humanity through form and concept.Archipenko’s Walking Woman (1913-1915) is an angular geometric structure that presents the viewer with innovations of the artist’s contextual world. This sculpture demonstrates the use of Cubist principles applied to the timeless sculptural subject of the human body. Walking Woman defies the traditional values of sculptural solidity in its time of creation. It was created in the bronze medium standing at approximately 67cm in height. The art making process of bronzes are a lengthy and highly skilled practice – the reason why Archipenko’s sculpture took 2 years until completion. Bronze sculpture requires the complex methods including rubber molding, wax chasing, investing, metal chasing, finishing and patination – each step an integral component in the bronze sculpture creation.

Walking Woman has a visual balance of positive and negative space, providing a sense of aesthetic equilibrium for the viewer. Although the weight of the figure is evenly centred, the irregular composition of shape and line overlap and unite. This collectively produces a fluidity of sharp, directional edges. Numerous fragments of perspectives are presented to the viewer simultaneously at any angle. The dynamic representation of the female figure can be viewed and appreciated from several abstract viewpoints despite its seemingly frontal stance. This was understood in Archipenko’s context as a startling defying choice against the Neoclassicist values of traditional art. This kept Archipenko distinctly apart from the fellow artists of the era in terms of aesthetic and principle.

Walking Woman has a visual balance of positive and negative space, providing a sense of aesthetic equilibrium for the viewer. Although the weight of the figure is evenly centred, the irregular composition of shape and line overlap and unite. This collectively produces a fluidity of sharp, directional edges. Numerous fragments of perspectives are presented to the viewer simultaneously at any angle. The dynamic representation of the female figure can be viewed and appreciated from several abstract viewpoints despite its seemingly frontal stance. This was understood in Archipenko’s context as a startling defying choice against the Neoclassicist values of traditional art. This kept Archipenko distinctly apart from the fellow artists of the era in terms of aesthetic and principle.

His 1913 painted plaster sculpture Carrousel Pierrot is a piece that further reflects his exploration of the human form and its relation to motion and space. At a height of approximately 34cm, the figure stands unbalanced; leant forward as if captured in action. His sculpture celebrates the body in motion and is of equal importance to the voids of space enclosed by the figure’s unattached limbs. Again, a recurring theme can be appreciated in Carrousel Pierrot through his representation of positive and negative space. The whimsical figure is abstracted to a stylised emphasis on shape, contours and line of the body. Archipenko’s sculpture reflects his fascination with the abstraction of the body. He draws the viewer’s attention away from reality and to the potential of structural elements.

The sculpture’s surface is painted with polychromatic colours in brilliant tones – yellows, blues and greens unite in random, shapely disorder, much like the Cubist fragments of a Picasso painting. Archipenko revealed his inspiration behind this work was a festival where “dozens of carrousels with horses, swings, gondolas and airplanes imitate the rotation of earth”. His influence from the world of puppetry, jesters and harlequins mirror his inspirations of the absurd and the imagination of his artistic idols, most notable Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp. His representation of concept is personified through his perspective of intriguing visual energy, informal balance, and how the human form interacts with the freedom of space.

The sculpture’s surface is painted with polychromatic colours in brilliant tones – yellows, blues and greens unite in random, shapely disorder, much like the Cubist fragments of a Picasso painting. Archipenko revealed his inspiration behind this work was a festival where “dozens of carrousels with horses, swings, gondolas and airplanes imitate the rotation of earth”. His influence from the world of puppetry, jesters and harlequins mirror his inspirations of the absurd and the imagination of his artistic idols, most notable Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp. His representation of concept is personified through his perspective of intriguing visual energy, informal balance, and how the human form interacts with the freedom of space.

Alexander Archipenko presents his audience with a unique perspective of seeing the body. This notion represented in his sculptural work prizes structure over realism while deconstructing the values of art conventions. Archipenko discovered the relationship between modern and historical art styles to form a creative and conceptual niche of his own. Archipenko’s rhythmic, abstract and beautiful sculptures preserve the traditional subject matter of the human body however heightening its potential to explore new boundaries.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The Gondolier is amazing, glad that you decided to write about Archipenko!

Thank you for reading!

Great article! His King Solomon sculpture is stellar.

Thank you! You’re not wrong there, he has a really wonderful body of work.

Thank you for introducing me to such a brilliant artist! Really interesting article; I learnt a lot from it. I love the quotation about adding to Cubism.

Thank you for reading! I studied Archipenko in school years ago and his work always resonated with me.

This is indeed a great essay. Thank you for writing it. Covers Alexander to the spot.

Thank you for reading!

Fascinating article – Archipenko’s work is absolutely beautiful! I’ll be looking out for opportunities go to see it in real life 🙂 also, your writing complements such wonderful pieces of art.

Thank you very much Camille! He was based in America for many years so I’m sure that’s the place to start 🙂

I am curious, did you research who his teachers were? I understand that he was greatly influenced by Cubism (as many artists in Paris were) and that he departed from it to create his own style, but the sinuous and curvy nature of his work greatly resembles some more “primitive” human sculptures by Bourdelle and also the open fluidity of Zadkine’s ouevre.

There is definitely an abstract I’ve principle at work here.