Antagonist-Centered Stories: What Can We Learn?

Ever since there were heroes, there have been monsters to challenge them. To be more accurate, the monsters came first, representing the fears and struggles every person has. The heroes were created to show that adversity can be overcome, that dragons can be defeated.

Over time, the monsters have become more human-like and many have been replaced with villainous people, murderous maniacs, tyrannical rulers, or ambitious conquerors.

In recent memory there has been an influx of stories where the protagonist, traditionally a heroic type, has been replaced with a character one would expect to be the antagonist, the villain. Is this the ultimate in “humanizing” the monster? Can we take the same lessons from these inverted stories? Should we be drawing lessons from villains?

Monsters Don’t Live Happily Ever After

Many antagonist-centered stories are “tales twice told,” retelling an established story from the perspective of the villain. This includes books like Seriously, Cinderella is SO Annoying and The True Story of the Three Little Pigs and some TV episodes of Once Upon a Time. From these examples, a trend is already emerging: fairy tales commonly receive the villain protagonist treatment.

Fairy tales are the stories we grow up with. Through repetition, we tend to learn them very well without trying, which means most of us are not likely to give them much deep thought. When a story comes along that seems like one we know so well but with a perspective shift, we are forced to reflect on the original again.

Of course, it takes more than declaring the villain the protagonist and retelling the same story to make us think. The protagonist traditionally has a relatable and sympathetic point of view. When the villain is in that position, we usually see him/her in a more sympathetic light than before.

In Once Upon a Time, the villains have usually lost their true love or something like that; their backstories are tales of failed fairy tale protagonists, and that apparently forces them to become antagonists. According to The True Story of the Three Little Pigs, the Wolf was trying to get a cup of sugar from his neighbors (the pigs) so he could make his grandmother a cake – considerably more sympathetic than “the bad wolf wants to eat the pigs.”

Even if these villain protagonists are unreliable narrators, we may still find ourselves relating to them, possibly against our better judgment. At the very least, we may entertain possibilities we had never thought of before; maybe we were wrong about these characters when we were young.

After so long considering these heroes and villains in terms of black and white, being forced to reconsider fictional right and wrong may make us rethink our assumptions about real-world “heroes,” “villains,” and “victims.” Before calling an unpopular politician “evil,” for example, the audience of these stories is encouraged to consider his backstory, his motivations, and his point of view.

In a video called “4 Disney Movie Villains Who Were Right All Along,” Cracked.com lists antagonists with motives that could actually be considered admirable. For example, in Beauty of the Beast, Gaston wants to marry a girl who everyone else just thinks of as “odd,” and also wants to save her from a hideous monster who seems to be manipulating her. “Nine out of ten movies,” the video says, “Gaston would be the hero.”

Michael Tabb, in an article in Script magazine, lists more antagonists with motives like “pride (Apollo Creed in Rocky), sustenance/survival (Dracula)…recognition (Buddy Pine in The Incredibles)…world peace (Ozymandias in Watchmen)…” and the belief that lawbreakers must be punished, i.e. Javert from Les Miserables. He also points out, “The list of motives I used as examples above are not necessarily evil. In fact, depending on their context, the same incentives can just as easily work for a protagonist” (emphasis added).

Antagonist-centered stories provide that alternative context and try to make audiences rethink their assumptions and consider how easily these admirable motivations can make people do “villainous” things.

With Great Power Comes Great Corruption

Another genre that seems to lend itself to antagonist-centered stories is superhero stories. While there are new stories about superheroes, or at least new reboots of old stories, coming out all the time, there tend to be similarities throughout the genre. The protagonist is usually a heroic bastion of morality, and his/her nemesis is the villainous antagonist.

Over time, a growing number of superheroes have been created with looser morals, more willingness to commit darker acts. We call them anti-heroes. Villain protagonists are like the ultimate anti-heroes – characters who believe their intentions are right but do things that many, including the audience and possibly including the protagonists themselves, consider outright evil. Stories focusing on this kind of protagonist are slowly becoming more popular.

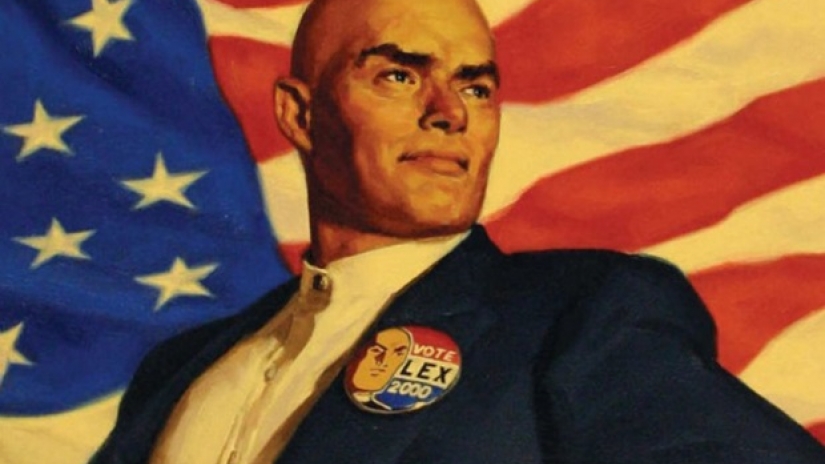

Lex Luthor considers himself a hero, using his superior intellect for the betterment of humanity by any means necessary and for protection against the false god known as Superman. Stories focused on him (the Lex Luthor: Man of Steel miniseries, for example) show him as more relatable than most of us would normally like to admit.

The villain protagonist of Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog is portrayed as sympathetic based on his motivations. His superhero nemesis is a self-centered jerk, so the audience is even more likely to root for Dr. Horrible.

But when Dr. Horrible wins in the end, he gets everything he thought he wanted at the expense of what he really wanted most. The audience feels sorry for him even though he is the villain and he won. The cognitive dissonance shows the quality of Joss Whedon’s storytelling and the power of framing the story from the traditional antagonist’s perspective.

Marvel/Netflix’ series Daredevil and Luke Cage have featured episodes focused on the antagonists Wilson Fisk, Cottonmouth, Mariah Dillard, and Diamondback. Through flashbacks, we see their sympathetic backstories. Although these stories leave out details that may have made the characters less sympathetic, they do make us feel sorry for the villains and maybe make us think their actions are understandable, if not justified.

One of the similarities across the superhero genre is the theme that “power corrupts.” Making the villain the protagonist – even for one comic book issue, miniseries, or TV episode – can show that the villain is not inherently bad but corrupted by power. Perhaps they had very little power before, and they are now willing to do anything to gain power and stay powerful. This further debunks the audience’s assumptions about black-and-white good and evil.

Additionally, showing the corrupting nature of power can be a commentary on human nature. Many people wish they could be powerful like the superheroes they read about or watch. However, because humans are flawed, we are generally more likely to use power for personal gain than for selfless acts of heroism. Again, the monsters come first, and then heroes rise up to face them. Antagonist-centered stories often portray the transition from “normal person” to “person with power” to “villain” as believably simple. So maybe we shouldn’t desire power quite so much.

On a similar note, identifying with the antagonist provides particularly relatable learning opportunities. As Emma Hetrick points out in her article on Locust Walk Journal, “we want to identify with the ‘good guys’ of any story because they’re the people we want to emulate…we don’t want to empathize with the antagonist of a story because that would bring to light the flaws within ourselves.” Hetrick sees identifying with the antagonist as an “opportunity to learn how to overcome our weaknesses.” True, some protagonists also overcome moral weaknesses, but in order to be role models for everyone these heroes reach nearly unbelievable heights of virtue. Villain protagonists are more realistic characters, not necessarily as role models but as examples of what we do not want to be but all too easily can become.

There are many video games that give players the option to be on the evil side (for example, the Dark Side/Empire in many Star Wars games), or let them choose whether to make the main playable character a hero, saving people, or a villain, destroying things and killing people on the way to some ultimate goal. Some of these games have multiple endings that depend on the choices the player made (a popular example of that is the Mortal Kombat games).

Prototype, as TVTropes.org puts it, “automatically assumes the player will choose to behave the way players ‘always’ behave in a Wide Open Sandbox game,” that is, like a remorseless villain. One interpretation of all this is rooting for a villain and even taking some responsibility for their villainous actions can be cathartic, which just demonstrates that we have more in common with the villains than we’d like to think.

The Good, the Bad, and the In-Between

There is an important trend in the growing category of antagonist-centered stories: redemption. Not every villain protagonist achieves victory like Dr. Horrible, but the rest don’t always lose to their heroic counterparts the way the Wolf did in The True Story of the Three Little Pigs. Sometimes the villain becomes a better person, even a hero, by the end of the story and secures a happy ending.

This theme of reformed villain protagonists often comes up in the superhero genre. Stories like Megamind and Superior Spiderman explore what happens when a supervillain defeats the superhero and becomes the new protagonist. In both of those examples, they become much more heroic because it seems heroes are a necessary part of the story they are in. These stories have the advantage of surprise, and their unusual circumstances can teach unusual morals. In many of them, the villain finds life without opposition not nearly as pleasant as they might have expected – a further cautionary tale.

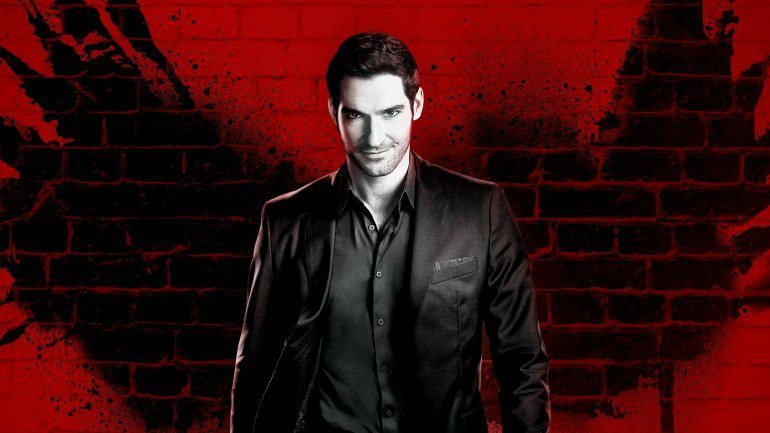

When we allow our villain protagonist to reform, many possibilities spring up and we expand into many different genres. The comic book series turned TV show Lucifer focuses on the infamous fallen angel of the Bible. He does not see himself as a villain; he sees God as the villain. From a third-person perspective, though, God may still be seen as a force for good, and Lucifer as a villain protagonist with a sympathetic backstory who is slowly being redeemed. This has some dramatic implications. To paraphrase a line from another character, “if you can be redeemed, Lucifer, anyone can.”

Most people wouldn’t consider the main character of Jerry Maguire a villain protagonist. This is because Maguire’s redemption arc begins close to the beginning of the movie; he realizes that he and his industry are morally reprehensible and decides to change himself. He regrets that decision at various times in his story, but he ultimately makes it work. He “wins,” as the protagonist is expected to do.

What Does This Mean?

Whether or not an antagonist-centered story “works” is subjective. Each member of the audience decides for themselves whether the writing and/or acting makes him/her sympathize with the villain protagonist, reconsider their assumptions about morality or power, or have whatever other reactions the storyteller was trying to evoke. But there are some people who enjoy these stories and draw lessons from them, which is all that’s required to classify antagonist-centered stories as a viable sub-genre. The more important question is whether or not storytellers should tell more antagonist-centered stories. Are they “good” or “right”? This is also considered subjective, but arguments can be made.

As previously mentioned, these stories can teach audiences not to assume people are “evil” without learning their backstories and motivations and that even the worst anti-hero can do good and be redeemed. These are, in theory, good lessons to learn. On the other hand, some would argue that not everyone should be forgiven because of a sympathetic backstory. There is push-back against Lucifer, for example, from Christian communities who cry that making the Devil a hero runs contrary to the whole Christian belief system.

Making audiences reconsider right versus wrong isn’t necessarily a good thing either. Villain protagonist stories could be called arguments for moral relativism, a philosophy many people disagree with. Again, many villain protagonist stories are re-imaginings of fairy tales or the superhero genre, the stories children know best. If antagonist-centered stories are teaching moral relativism, they’re most likely teaching it to children. Whether that’s a philosophy one agrees with as an adult or not, is it a philosophy we want children to learn?

Ultimately, though, antagonist-centered stories work as cautionary tales. Audiences can be cautioned about how corrupting power can be and how corrupt humans already are. If we find ourselves sympathizing and empathizing with Lex Luthor or the Big Bad Wolf, the correct response is to be encouraged to be better than them. This can be an even stronger motivator than the incredible standards set by heroes.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I like morally ambiguous characters; all this ‘good guy,’ ‘bad guy’ stuff seems a bit simplistic.

I couldn’t agree more! Aren’t we all just people that fall somewhere in the middle, ultimately it’s our decisions that are good or bad? A backstory or choice doesn’t make us who we are, we define that on our own and how we want to be portrayed to the rest of the world. It seems so ridiculous the notion that characters can only be one or the other when this doesn’t reflect real life.

Walter White. Just a brilliant character, and one that is constantly plays with audience sympathy. By the end of Season 3, you’re not sure whether to condone or condemn his actions.

Are anti-hero’s on televsion actually just portrayals of people that actually show some character defects? (like everyone in the world).

Rather than the pure as the driven snow heros who normally appear on T.V.?

That’s certainly what the villain protagonists and anti-heroes would like you to think. The problem is the unreliable narrator trope; plus, when they embrace their character defects rather than working on fixing them, they become classified as villains rather than heroes.

Interesting how male anti heroes are not presented as a example of a good way to be, whereas female anti heroes often are.

Hmm, good point. The female anti-heroes and villain protagonists like Maleficent and the female villains in Luke Cage and the Defenders are often victims of something, and their stories are about overcoming the trauma or the limitations, albeit through reprehensible actions. Many people want to empower women, but we’re not in such a rush to praise men, even when they’re also victims and reacting in similar ways.

Always Lisbeth Salander for me. I started reading Dragon Tattoo not really knowing what to expect and I found that I was almost cheering her on.

I have never understood why they changed the title of the first one. If it was directly translated it would be “Men who hate women” which is an absolutely terrific name for it. Couldn’t have done much better with a better name though!

Very interesting article. I love the mixture of television and movie characters, as well as the analysis and use of different genres.

I enjoyed your article. I have always liked “greyer area” villains and you present interesting points to further discussion on them.

Interesting. There was a recent furore over the book and film Gone Girl (written by a woman) – she was criticised by some feminist voices for portraying a female character with deplorable character traits. Maybe a reflection that as a society we don’t like to view women as capable of doing bad things. In fact i think the author rebutted by saying that we shouldn’t limit female characterisation and that women should be able to explore a darker side. But i guess the dominant narrative is that it is men who display bad character, not women.

Amy is a twisted and utterly compelling anti-heroine – and, refreshingly, the author doesn’t punish her for it.

I wouldn’t class Amy as an anti-heroine, she goes beyond that to become an antagonist. To me your typical antihero usually seeks some form of redemption or has at least a glimmer of goodness in their character – I felt in Gone Girl “punishment” would have produced a much more satisfying ending, although I can see why the author chose not to go down that route.

Most of Toni Morrison’s heroines…

In modern popular fiction there are good antagonist centered characters like Omar Little, Tyrion Lannister, Jack Sparrow, Spike, Sherlock, Tony Soprano, etc etc.

As far as I know, the Sopranos and the characters from Game of Thrones do fit the villain protagonist model. But I’m not sure about Jack Sparrow. He’s an anti-hero, but he’s not actually villainous.

And Sherlock? Who would ever consider him a villain? Just because he comes across as a jerk doesn’t mean he’s evil.

And Spike is a villain who redeems himself and becomes a hero. He would only be a “villain protagonist” in certain parts of his backstory.

I don’t mean to sound pedantic, but my article applies to a specific brand of character and getting off-brand alters the takeaways and what I was hoping to accomplish.

Jax Taylor in Sons of Anarchy was an awesome character and very much a villain.

How about Mal Reynolds from Firefly? Thief and smuggler, not averse to cold-blooded murder, yet sometimes almost a Robin Hood figure. Fiercely loyal to his crew but blunt-spoken to the point of offensive, risks himself to protect the Tams, but you’re never completely sure he wouldn’t sell them out if the price was right.

I’d throw in Spike from Buffy/Angel as well.

Unfortunately, neither of your examples actually fit the “villain protagonist” model I was talking about. Mal and his crew are criminals, yes, but they are framed as heroes, not villains, because the Alliance is seen as overbearing and therefore evil. Spike is a full-on antagonist who becomes more sympathetic and relatable and then redeems himself, becoming a hero-protagonist.

That probably sounded pedantic. I wrote the article about a particular brand of character and it’s important to stay on-brand. We can probably learn different lessons entirely from anti-heroes like Mal Reynolds or Heel-Face Turn characters like Spike.

Previously, female anti-heroes seemed to be either comedy monsters (Patsy Stone, Charlie and Alan Harper’s fantastically appalling manipulative Evelyn mother in Two And a Half Men) or they are thwarted and punished for being “self-serving” and refusing to conform (Samantha Jones) or they’re unglamorous and abrasive (Roseanne).

Nowadays, they are beasts.

I like good characters turning bad, or vice versa, as long as it’s handled well.

Yes! For me, as long as there is some consistency and logic to why they may have turned bad, and there has been no point at which the audience has been lied to (as opposed to the character lying to other characters), i.e. where we see scenes that should not have conceivably taken place if they had been bad all along, then it’s fine by me.

The biggest turn-off for me is that once some series has been a success we get endless re-hashings of the same thing over and over again.

This was a really interesting read where I found myself nodding multiple times! It seems like such a basic concept to be hiding under our noses, but perhaps that’s because most of us use these modes as an escape and don’t want to be reminded of our less redeemable qualities.

Characters who evolve from being just ‘good guys’ or ‘bad guys’ and become morally grey to the point where you don’t know whether to root for them or hope they get brought down are my favourite kinds of “protagonists.”

The first that comes to my mind is DeathNote’s Light Yagami, but I loved all your examples and ideas too. Awesome work!

This is interesting and a really thought provoking article… two thoughts: the first is the philosophical world view that most of these characters share which seems to be very utilitarian. The world around them in a means to an end; Walter White sells drugs to pay for chemo, Lex Luthor does “good” deeds in order to best Superman & prove the superiority of the human race, Dr. Horrible wants to rule the world, etc. I agree that they all work to caution us but I might suggest that they caution us about the dangers of utilitarian thinking which seems to dominate “villainous” heroes (how very Heideggerean…). Second, I wonder if these works could be coined as alternate perspective pieces? Antagonist-centered narrative only functions in works that have established traditions of the character as an antagonist (I.e. Lex Luthor and Doc Oc as Superior Spider-Man). It doesn’t work as well with characters like Jerry Macguire or Walter Ehite. Just a thought.

You’re right, many stories like this are “tales twice told.” But I’m sure you can find a story that has a meth cook or a talent agent in a villain/antagonist role. Jerry Maguire and Breaking Bad offer the reverse perspective, just not of those specific pre-established characters. It’s a sign of creativity and storytelling skill.

I’d have to say that the two biggest antagonist driven stories that tend to come to mind easily are Wicked and Maleficent. These are two stories that take very old characters that, for decades, have been seen as the main antangonists of their stories until they get turned on their head. It’s easier to be more interested and relate more to these stories because they are flawed. Often a protagonist that wholly good is hard to relate to because humans are complex. It is easier to relate to someone who walks a grey line, and it is generally more enjoyable to see that sort of story played out in book, on the screen, or through a controller. We enjoy being a little evil, and we understand what it is like to be misunderstood. We also typically see these “villains” get antagonized by people that are often thought to be good. It has definitely gained popularity, and has given commercial rise to a new trope that has breathed fresh air into centuries old story styles.

In Buffy, Angel quite literally turned from closest ally to sworn enemy during the whole of the latter half of season 2. OK it was technically an alter ego but his relationship with the Scoobies was never the same after that. Faith did a similar volte face in Season 3, as did Jonathan in Season 6. Spike, meanwhile, went from killing slayers to shagging them. Then in his eponymous TV show Angel allowed vampires to feast on some humans he disliked while still carrying his soul, Wesley became an outcast after kidnapping Connor, Gunn allowed his personal feelings about demons to get in the way of doing the right thing, and of course Cordelia became infected with Jasmine. Plus of course in the final season the antagonists were actually taken over by the heroes.

Meanwhile, over in the Trek universe, over the course of its canon the Federation made it up with the Klingons, the Romulans…

Not sure I agree…

– Angel wasn’t a secret baddie all along: he was a goodie until he got cursed (well, technically un-cursed), and became a goodie again later when the mystic stuff was sorted out.

– Faith was deeply troubled from the start: she tried to be a goodie, but her fall to the dark side was signposted a mile out.

– Jonathan was always portrayed as fundamentally weak, and his villainous hijinks in Season 6 were foreshadowed by similar shenanigans on a smaller scale in Season 4.

– Spike went through a character development arc that lasted at least three whole seasons, from out-and-out villain through neutered vampire and reluctant ally (mainly because he got to hit things) to genuine hero.

Yeah, Lord is right. A protagonist who turns antagonist or an antagonist who turns protagonist does not a villain protagonist make. They need to be both a villain and a protagonist at the same time.

These shows are updated versions of Dallas. The appeal is what it’s always been: getting to identify with rich people who can get away with anything, but also getting the moral satisfaction of seeing them suffer and feeling they are less moral that we.

Two obvious favorites of mines are The Shield’s Vic Mackey, and more interestingly, Walter White from Breaking Bad.

I find it hard to sympathise with Mackey, which I would imagine would be important for an anti-hero, but I’ll cheer on Walter all the way.

Just popping in to say, I’m thrilled this got posted, and that it’s generating so much discussion. 🙂

I really like shows and movies that have antagonists as the main character because I feel they’re often way more complex and interesting than the typical ‘hero’ character. I also agree that some people may watch these types of stories because of the possibility of the anti-hero’s redemption. If people are trying to relate to a movie, they want to see that there is hope of redeeming themselves if they haven’t been as entirely “good” as the idealistic hero. I’d be interested to see how people would react to an antagonist-centered movie where the antagonist has no redeeming qualities, no sympathetic past and is just “bad”. I don’t think we would be as invested in what happens to the character or the story.

Take Walter White, the leading man of Breaking Bad. His character is not a polar good or bad guy, but as you suggest far more complicated and interesting. This character development is one driving force that allowed the show to continue through its unrealistic scenarios for so long.

All humans have potential for good and evil. It is the struggle to overcome the evil within which appeals to so many, such as Rumple fighting his lust for power and his fear of losing it. This creates a sympathy for the devil scenario. Just my thoughts on it.

Yes! I originally had a paragraph about villains reforming, like the ones in Once Upon a Time, who then feel tempted by their old evil ways. It’s a fascinating version of the “man vs self” conflict.

How can we not rejoice in the chaotic beauty that was the character Detective Victor Samuel ‘Vic” Mackey.

If ever there was a master of the morally flexible, a power-manipulating machiavellian, a connoisseur of crisis-management, a cash hungry, hooker-caring, cop whacking, door crashing, super snarling, mega conflicted Uber Bastard of a ‘PO-Lease’ officer, surely ”tis he.

I’ll never forget the ending of the first episode of the the first season of The Shield, Jesus H ‘Tap Dancing’ Christ it was dramatic.

A set of complex, morally ambiguous characters who compel us to relate to them despite their often troubled nature and gaping collection of character flaws.

I love this view. I think it stems a lot from real life. We can learn a lot from a good role model, but how many of us learn the path not to walk from an adult in our lives that made constant poor decisions.

I absolutely love story arcs where the villain is humanized. That may sound surprising when my favorite novel is “It” by Stephen King and the main antagonist in that book is soulless monster clown that eats children, but go figure. Characters that can be identified with (Loki from Thor mythos/Marvel), and even characters that come from the dark side to the light (I could say Darth Vader from Star Wars, but I think I’ll go with Zuko from Avatar: The Last Airbender) are always intriguing and wonderful to watch develop. Great article!

A great read. I do love these types of anti-heroes. I am particularly enjoying the portrayal in Lucifer at the moment. One of the interesting aspects of this is the idea of what makes an antagonist, as you identified in relation to Gaston, that a villain can often be positioned as such because of the choice of narrative view point. This does make it interesting to then consider how many other villains have a valid position, or supposedly heroic characters that may not be from a different position (post-colonial and feminist readings often have a lot to say about this). Thanks for the good read.

The definition of an anti-hero is a flawed hero, so they have some heroic attributes but they’re also flawed on a personal level. Ultimately an anti-heroine should be someone one looks up to but also recognises as a real human being with flaws.

These are super scary characters. The ‘Suits’ show is just as scary as Ozark.

I find an antagonist story to be utterly refreshing. It opens up perspective into the “bad guy” of the story’s motives, which oftentimes I feel are explained with bias. Usually the “good guy” receives an explanation from a bad guy’s victim or none at all. I was the type of person as a child that I would always ponder why the villains in my favorite movies chose to do wrong. I like that the exposure to more complex characters through the antagonist story, because it brings a new perspective to film and TV. I really enjoyed this article, and was hooked by your mentioning of The Real Story of the Three Little Pigs. That was one of my well-loved books at story-time.

love

That’s why I like he new Infinity War movie. No spoilers, but it is the most developed Marvel super villain because we see his motivation and background. He truly believes that what he’s doing is the right thing. A lot of the other villains have no depth or are the “evil” version of the Protagonist. This happens in Iron Man, Doctor Strange, and Ant Man.

I also think it’s important to note that we more likely support the “antagonist” if it is in a comedic background. MegaMind, The Real Story of the Three Little Pigs, and Dr. Horrible are all backed by comedy.

Absolutely! The fact that the villain is not simply a canvas painted in broad strokes of evil, but is actually nuanced and identifiable, makes the movie for me. Too often we seen villains who are caricatures, who are pure and undiluted evil, but their creators forget the simple fact that we all have flaws and traits that place us somewhere in the middle. The subtle, relatable villain is far more engaging than the broad-brushed baddie.

The simple good/evil type story doesn’t really hold up to reality, so I’m glad that there’s a push towards villainous protagonists. Their stories can be far more interesting than the typical good guys win fare.

This is a great read! I really like the point you brought up about the breakdown of stark good vs evil. Javert has always been fascinating to me because much of Les Mis is a story where everyone is doing what they think is right, and they all have high points and flaws, and it’s just much more compelling than the sort of basic “killing bad, hero good” sorta thing. Everyone’s bad and good, let’s talk about why.

I think this topic is very interesting due to why we love a villain as the protagonist. Why does this say about our society? Dr. Horrible is also one of my favorite pieces of media ever.

This is such a smart article. I love the idea of using our understanding of a villain or antihero’s flaws to improve ourselves. A good character should always force us to reconsider our own actions and behaviors

As someone who loves both our chosen one characters – those who embody a high moral compass – as well as loving morally grey characters, I really like this article. Especially where you talk about moral relativism, which is quite common to see in a lot of antagonists/villains these days .. particularly for a certain Marvel villain if anyone knows who I’m talking about. Anyways, it’s important to have three-dimensional antagonists otherwise the story is boring. When you root for the ‘hero’ of the story, but you can also understand the intentions of the ‘villain’, it makes a story that much more complex and interesting.

I absolutely loved this article. This is a subject that I feel incredibly passionate and have also written about in the past. When you mentioned the ability to play as both a hero and a villain in the Star Wars games gave me an idea. What about a game where the character you play as is both hero and villain? Consider if you will “Star Wars: The Force Unleashed”. The main character, Starkiller, goes through the majority of the first game murdering Jedi and committing other evil acts at the behest of his master, Darth Vader. Vader abducted him as a child and trained him to be a ruthless Sith. He is then betrayed by Vader and realizes that he was never meant to be a Sith Lord, but a Jedi Knight himself. The second half of the first game and its sequel show that he has assumed the role of the protagonist (or, possibly, the anti-hero). Though he was trained by the Dark Side, he was cast aside because he also had Light in him.

You have given me so much to think about. Thank you.

Do me a favor; check back here on Monday; I’ll have a link to something you should read.

Here’s my full reply to your comment: https://thecorrelation1148.wordpress.com/2018/05/14/a-man-called-starkiller/

What a refreshing article. Truthfully, I’ve always been more drawn to characters with morally ambiguous personas than squeaky clean ones, they’re so much more realistic than characters who are only good or evil. I like the layers that these characters present because in real life we won’t come across people who are “evil” for no reason. Although most of the works we consume for entertainment are fictional and people know better, it would do the world more good to showcase people that are more like the ones they encounter in real life. That mean’s depicting protagonists with flaws and antagonists with sympathetic aspects. This way maybe people would be more sympathetic and understanding towards one another? Only showing stories based on the heroes’ perspective are very one-sided and hard to believe. We can’t always rely on the winner’s side of the story as history has shown.

For myself personally I like a story in which you like the bad guy just as much as you like the good guy! I think of TV shows like Black Lightening while the bad guy here is an insane psychopath who we are supposed to despise because of how terrible he is I find him fascinating and charmingly evil. Another villain in TV that I love to hate is Killgrave from Jessica Jones. David Tennant does an amazing job here of bringing to life a character that is so evil and terrible that I utterly despise him and find him extremely creepy, but he does everything with such charm that he becomes a character that makes us love the actor even more. Finally, probably one of the biggest examples of a “villain” or antagonist in which we are never really sure which side of the fence they are on is Loki from MCU (I mean come on do we ever really know if he is good or bad, or if he actually dies!?)

He that wrestles with us strengthens our nerves and sharpens our skill. Our antagonist should be our closest friend.

Hello, everyone. In case you’ve read all the way down to this part of the page, you might be interested in this other Artifice article by Emskithenerd: https://the-artifice.com/byronic-hero/

Byronic heroes seem remarkably similar to villain protagonists, so it’s easy to confuse the two concepts. Indeed, many of the commenters on my article have made that very mistake. Read Emski’s article, and perhaps you’ll better understand the distinction.

I personally prefer a protagonist as the main character, but that’s just me.