La Cabina: Creating Horror from the Absurd

In Madrid’s Chamberí district there is an anonymous, gated service road that leads to an equally anonymous, privately owned plaza. Compared to other, more colourful plazas in the city, this one is unremarkable – and yet it hides a secret. In the long, hot summer of 1972, during the twilight years of General Franco’s 1 autocratic rule, the late Spanish film director, Antonio Mercero, 2 chose this location to shoot the opening scenes for what is arguably his best known work outside of his native country – a controversial short film titled La cabina (The Telephone Box a.k.a. The Booth/The Cabin). 3

Part black comedy, part psychological horror, La cabina won Mercero the 1973 International Emmy Award for Best Fiction and soon after gained a cult following. In style and content the film occupies the middle-ground between Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone and Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror, but before venturing into the Kafkaesque world of that innocent looking telephone box, let’s take a moment to briefly cover the career of the man behind the camera.

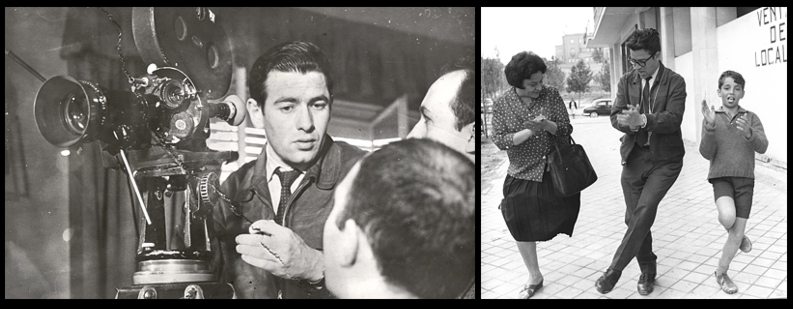

Born on the 7th of March 1936, Antonio Mercero Juldain (to acknowledge his full name) initially graduated in Law, before studying film making. He made his directorial debut with a short film about a shepherd boy, titled La oveja negra (1960) 4 and in 1962 he won his first award, for the children’s short film, Lección de arte. 5 Post-graduation, Mercero worked on a variety of self-penned projects, also paying his professional dues as an assistant director, a 2nd unit director and screenwriter, before breaking into television in 1968, with the documentary series Fiesta. 6

The 1970s and ’80s saw Mercero perfecting his directorial style, both in film and television. Amongst his many credits is the drama series Crónicas de un pueblo (1971-1973) 7 – essentially a reflection of Franco’s idealistic vision of small-town life – although he actually left the series in 1972, on ideological grounds. Building on his success with La cabina, Mercero’s comedy-drama about a rebellious three year old boy, La guerra de papá (1977) 8 and the international award winning war story La hora de los valientes (1988) 9 secured his position as one of Spain’s finest directors. Meanwhile, the TV series Verano azul (1981-1982), 10 which followed a group of youngsters on an adventurous summer holiday, had proven to be so popular that even to this day it remains one of Spain’s most loved domestic dramas from that decade.

La hora de los valientes (1988) and Verano azul (1981-1982).

Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium success continued to find Mercero, most notably with Farmacia de guardia (1991-1995), 11 a comedy series about the day-to-day running of a pharmacy, and the critically acclaimed, award winning film, Planta 4ª (2003), 12 set in a children’s cancer ward, but sadly personal tragedy was already on the horizon. His last film, ¿Y tú quién eres? (2007), 13 was a family drama about Alzheimer’s, all the more poignant for barely two years later he was diagnosed with the same disease, retiring from professional life shortly thereafter. 2009 also saw a fitting, final addition to the many honours Mercero had received across half a century of film making, when the Spanish Academy of Motion Pictures and Arts selected him for an Honorary Goya Award, generally regarded as the Spanish Oscar.

“In all of my works I have used three concepts: pain, love and humour…It’s a strange cocktail, I know, and often I’ve asked myself how I could mix elements potentially so different from one another. But, in practice, they have been landmarks in developing my creations.” Antonio Mercero. 14

Mercero died at the age of 82, on the 12th of May 2018, at home and surrounded by his family. He had always wished to leave this world whilst watching his favourite American musical, Singing in The Rain. It would be nice to think his wish was granted. To friends, colleagues and numerous fans, he will be remembered as an intelligent, kind and humble man – albeit one with a dry wit, a mischievous twinkle in his eye and a keen sense of the absurd.

By way of a personal recognition of Mercero’s contribution to the psychological horror genre in particular, this article will take an in-depth look at the making of La cabina; from origin and development, via government interference, to eventual international acclaim. However, this is also a story about a simple idea that inadvertently gave rise to a bizarre paranoid delusion that, in its own way, contributed towards La cabina becoming a Spanish cultural icon. So, for those readers unfamiliar with this unique slice of Spanish film making history, let’s begin by answering the question: what’s it about?

The Telephone Box Plot

Four anonymous men from an unnamed telephone company install a shiny red telephone box in the aforementioned plaza then depart in a flatbed lorry. Minutes later, after walking his young son to the school bus, a middle-aged man enters the phone box and attempts to place a call, only to find the line is dead. Meanwhile, the door closes slowly and traps him inside – like a specimen in a killing jar.

What at first appears an absurdly comical situation becomes increasingly embarrassing for the man when, during failed attempts to free him, a crowd gathers and views his predicament as a source of entertainment. Shortly after the police and fire brigade arrive on the scene, the telephone company men return, load the phone box and its occupant onto the flatbed then exit the plaza, with the crowd gaily waving goodbye. Driven through the streets of Madrid, like a parody of a Holy Week procession, the protagonist’s journey grows ever more perplexing and when he sees another man trapped in an identical phone box, his discomfort rapidly transforms into desperation, then a genuine fear for his life as he realises the real nightmare has only just begun.

Even to this day the climax of the film leaves a lasting impression on the viewer, and for good reason. Mercero offers no explanation for why kidnapped middle-aged men are being abandoned in a secret underground warehouse, far from human habitation yet populated by desiccated corpses in phone boxes. The dénouement simply shows a replacement phone box being installed in that same plaza and its door left open invitingly – and yet from the first scene to the very last, not a single drop of stage blood has been spilt. Therefore the true horror of the piece lies entirely in the mind of the viewer. So, with that being said, it’s time to look at how La cabina came into being.

Three Spaniards Walk into a Bar

Early in 1972, following a regular Monday morning business meeting, Mercero’s close friends, the film maker José Luis Garci 15 and the screenwriter Horacio Valcárcel, 16 took him to lunch at their favourite watering hole. The trio chatted about the news, football and, not surprisingly, film making, during which Mercero mentioned a surreal comedy sketch he’d begun writing in 1970, but had later abandoned. 17 Allegedly based on a short story by the Spanish journalist and writer, Juan José Plans Martinez, 18 its subject was a man attempting to escape from a sealed telephone box.

The idea greatly amused Mercero’s companions. Valcárcel helpfully suggested a few extra details whilst Garci wondered how Alfred Hitchcock would resolve the dilemma. Consequently, Mercero’s sketch was resurrected and added to an anthology of short, fantastical tales already under development, collectively titled Trece pasos por lo insólito (Thirteen Steps to the Unusual). Unfortunately, when submitted to Televisión Española (TVE), the sole national television service at the time, the anthology was rejected, but Mercero wasn’t one to be dismissed so easily.

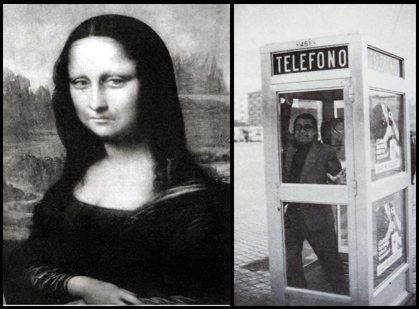

Artistic censorship was on the wane 19 as the regime was actively promoting a new, liberal image of the country in its latest bid to join the European Community. TVE had, likewise, adopted a more progressive policy, encouraging ideas that could be developed for international competitions. So Mercero later re-submitted the anthology and as leverage he cited the Crónicas de un pueblo series, which even the TVE executives conceded was little more than soft, pro-Franco propaganda. Therefore, from Mercero’s point of view, TVE owed him a favour in return. Accordingly, Mercero was ‘rewarded’ with a small concession. Two scripts were approved. One would later become the black comedy, La gioconda está triste (1976), 20 in which Da Vinci’s masterpiece loses her enigmatic smile and humanity is destroyed by a sudden cataclysm, and the other was Mercero’s surreal telephone box sketch. The rest, Garci later recalled, were “put into a drawer and never heard of again.” 21

The nascent La cabina script had been saved, but owing to professional commitments elsewhere Valcárcel was only involved with the early stages of development, leaving Mercero and Garci to see the project through to completion.

A popular cultural belief has it that one Spring day Mercero was taking a leisurely stroll through Madrid, pondering the phone box problem, when inspiration suddenly struck. He envisaged an eerie subterranean world in which middle-aged men were slowly dying inside telephone boxes, so he immediately contacted Garci (from a phone box, appropriately) and told his co-writer they had to rewrite the script, with their protagonist now permanently trapped and facing his own, inevitable death. Thus the direction of La cabina changed – from surreal comedy into something far more sinister – but, assuming that cultural belief is true, what might have inspired or influenced Mercero to include a subterranean world in the rewrite?

Influences or Coincidences?

Spanish cinemas, at the time, were dominated by Hollywood spy movies and Italian made ‘spaghetti’ westerns, 22 so consider this synopsis of a short scene from the 1967, Paramount Pictures spy-comedy, The President’s Analyst. 23 A man becomes trapped inside a phone box, is kidnapped by a team of anonymous men from a phone company, then transported to a secret underground destination. Sounds familiar?

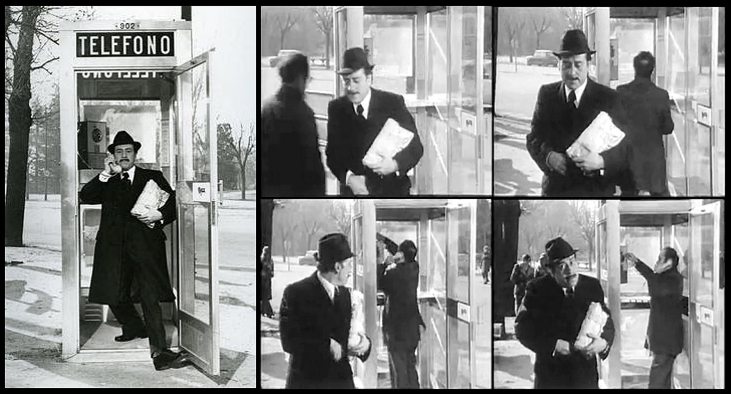

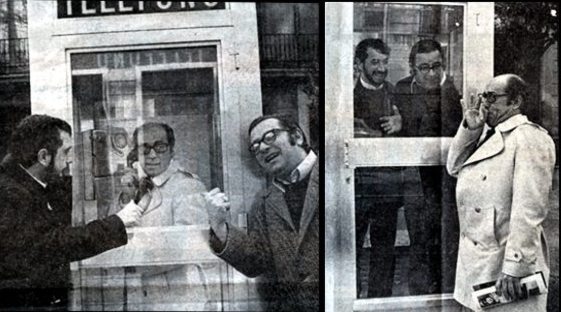

Also from 1967 is a Spanish TV advert, 24 part of the Las matildes series, 25 promoting the sale of shares in the telecommunications company Telefónica. Set in a small plaza, which looks remarkably similar to the location used in La cabina, a man mistakenly thinks he’s become stuck in a phone box, albeit briefly, after finishing a call. He even makes hand gestures against the glass panes, identical to those made by Mercero and Garci’s protagonist. Coincidentally, the actor in both this advert and La cabina is the same person – José Luis López Vázquez de la Torre. 26

Of course it could be argued that a scene from an American spy movie and an old TV advert do not constitute definitive proof of influence on the development of Mercero and Garci’s script. The above mentioned similarities are, admittedly, speculative suggestions made by this writer. Maybe Mercero never saw The President’s Analyst and perhaps Vázquez simply drew on elements of his performance in the Las matildes advert to help build his role in La cabina. Coincidences do happen.

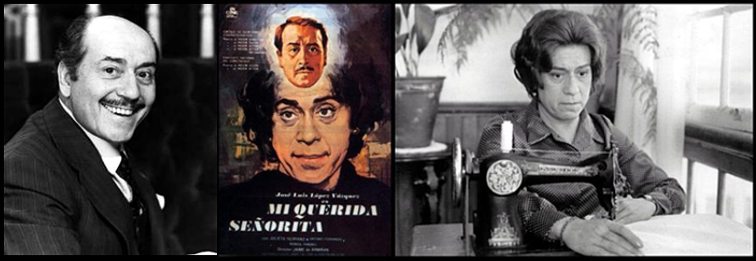

Casting the Grey Man

Mercero and Garci’s protagonist represented the stereotypical, middle-aged Spanish male: short, balding and moustachioed; coincidentally just like Vázquez. The character was essentially a cypher with no name, no backstory and definitely no future. Garci had wanted an actor of the same calibre as Marcello Mastroianni 27 or Vittorio Gassman 28 – contemporary stars of Italian cinema who could easily switch from comedy to drama within the same scene – whereas Mercero sought a mime and already had his sights set on Vázquez. A long-established star of the Spanish stage and screen, Vázquez had recently delivered a tour-de-force performance in the controversial black comedy Mi querida señorita, 29 in which he played a woman who questions her sexuality after discovering that ‘she’ was born male, but raised as a female. It was this role that apparently caught Mercero’s attention and in a recent (paraphrased) interview for Spanish television he commented:

“I thought that he had to be our grey man because he had the skill of a mime…[and could]…describe so many moods in such a short time with such force. The graduation of feelings [for the grey man] was very important and had to be done with a great actor who had to express everything only with his eyes.” 30

It was during a trip to New York in April of 1972 that Mercero convinced Garci they should offer Vázquez what has come to be regarded by many modern film critics as the defining role of his later career. Vázquez was working on Pedro Lazaga’s 31 El vikingo 32 when he received the script and he read it during a break in filming. Astonished by the themes Mercero and Garci were exploring with La cabina, Vázquez contacted his agent with instructions to rearrange his filming commitments so that once he’d finished Lazaga’s film he could focus solely on this new project. Sharing that same television interview with Mercero, Vázquez stated:

“The script seemed to me a very hard, very dramatic, tragic story. Above all else it symbolised the human state, the end, the life of human beings, the total annulment of the senses; disintegration. It caused me to feel restless.” 33

Restlessness is certainly a key factor in Vázquez’ captivating performance and his legacy is evident in the influence that performance has since had on other artists. From stage to screen to the small screen – and now the internet – his iconic role has been repeatedly copied, parodied or even just referenced in passing, becoming an internationally recognised meme in the process.

Joining Vázquez on this journey to oblivion was Agustín González; 34 another long-standing, character actor of merit, who became the second unfortunate soul trapped in a phone box. His was a cameo role, yet essential for reinforcing the unnerving quality of the middle third of the film. For the earlier scenes shot in the plaza, Mercero and Garci drew from a rich vein of Spanish stage and screen actors to create an array of everyday background characters. However, amongst the housewives and impudent children, authoritarian policemen and casual bystanders, several characters do stand out. There’s señor corpulento (the heavy-set man) whose hubris is brought tumbling to the ground by his inability to free the man in the phone box. There are the two middle-aged señoras who knit and revel in the spectacle before them, like twin versions of Madame Defarge 35 from Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. Then there’s the tall, gaunt pastry thief and the glazier with his logical approach to problem solving. Each in their own way helps accentuate the off-kilter, circus like quality of these scenes, whilst Vázquez skilfully plays against them and the crowd, en masse.

Communicating only by hand gestures and facial expressions, and resembling a tragi-comic figure from the era of silent films, Vázquez is that mime that Mercero sought. His timing is without par and every interaction is a mini master-class in itself.

Politics, Problems and Locations

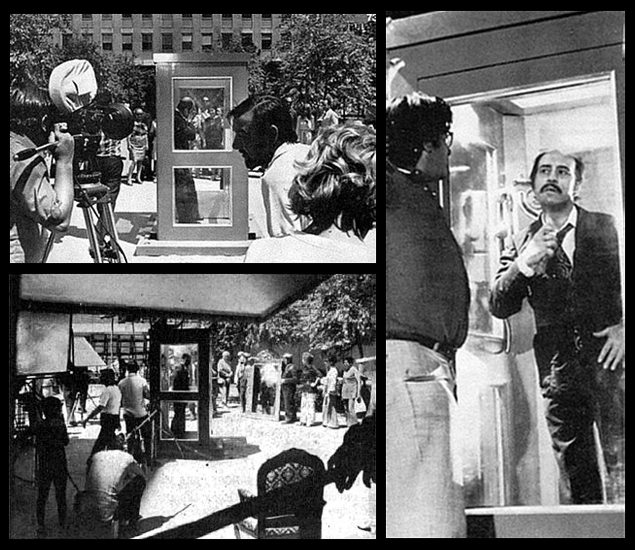

With a budget of 4 Million Pesetas (approx US$27,000 by today’s exchange rate) and an officially approved shooting script, Mercero still had to contend with government interference before filming had even started. The Ministry of Information and Tourism ‘requested’ that Mercero included footage of a modernising Madrid, to boost the international image of a new and vibrant Spain. Mercero complied, in a manner of speaking, but through the lens of his camera, modern apartment blocks became little more than glorified concrete boxes, the skeletal frame of a new build in process seemed barely able to support its own weight and images of a gentrified suburbia were juxtaposed against scenes of junk yards and rural decay. This was a Spain that was clearly still at odds with itself.

As any film maker knows, location is a powerful storytelling device – and none more so than the plaza – which encapsulates the protagonist’s combined sense of public exposure, isolation and entrapment. The surrounding buildings loom over the scene and effectively show the viewer a man inside a glass box, within another box, within another, larger box – a claustrophobic touch of Matryoshka doll symbolism from the inventive mind of Mercero.

Filming commenced on the 17th of July 1972, continuing into late August, but the initial seven-day shoot in the plaza proved to be a trial of endurance for Vázquez. In the suffocating heat of the relentless summer sun, the actor had difficulty breathing inside the phone box. The glass panes had already been replaced with perspex (for safety reasons, during a scene in which señor corpulento throws his weight against the box), so for close-ups the lower panes were removed to allow fresh air to circulate, thus giving Vázquez some small measure of relief. Coincidentally, Mercero and Garci had chosen the colour red for the phone box, to symbolise anguish and torment – and here was Vázquez genuinely suffering for his art!

Away from the plaza, locations included the grand sweep of Madrid’s Scalextric de Atocha elevated road system (since demolished) and the Tunel de María de Molina, the latter deliberately selected to foreshadow the terrifying climax. Passing through the eastern district of Hortaleza, Mercero mounted the camera on the rear of the flatbed, to capture both Vázquez’ silent pleas for help and the amused reactions from support actors outside the bar at No.32 Calle de Jazmin (today a café), although a few unsuspecting locals inevitably found themselves included in the footage after the film’s release.

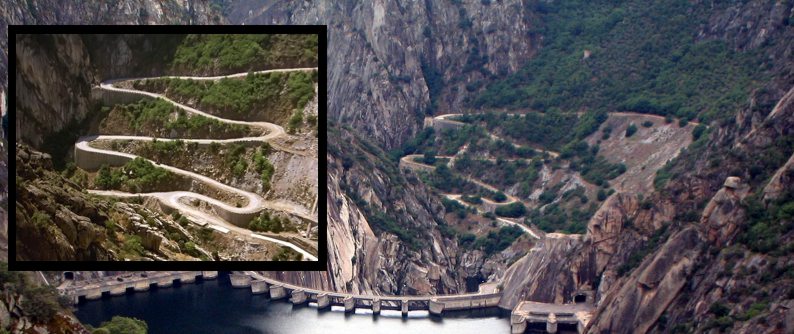

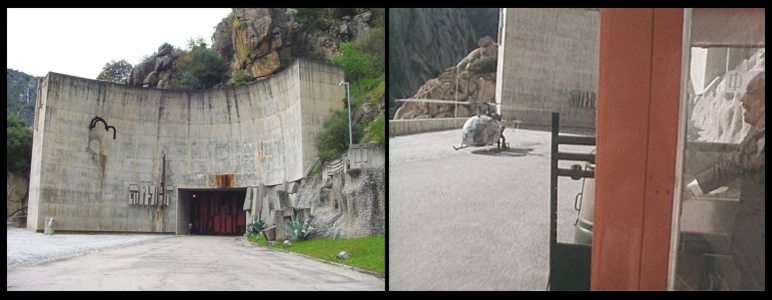

The recently completed cargo terminal at Madrid’s Barajas Airport provided a conveyor system, used to ferry the victim to his doom, which was seamlessly edited into the final scenes. To the west of Madrid, in the historic province of Salamanca, Mercero selected locations near the villages of Vitigudino and La Zarza de Pumareda. In Portugal, close to the Spanish border, a dusty road between Mogadouro and the Torre de Moncorvo became the stage for the symbolic ‘dwarf with the ship in a bottle’ scene, whilst the long, snaking descent to the town of Poblado del Salto de Aldeadávila featured during the protagonist’s journey into the deep of Las Arribes del Duero valley, marking the geographical Spanish/Portuguese border proper. Here too is where the approach road to the hydroelectric dam of Aldeadávila de la Ribera made an appearance, passing through the Spanish sculptor, Pablo Serrano’s La gran bóveda (The Great Vault) 36entrance to the dam’s internal road network; a symbolic highway to Hell blasted from the surrounding rock.

In the libretto for Mare Films’ 2014 remastered release 37of La cabina, the renowned Spanish film critic, Javier Tolentino 38states that Mercero originally intended to shoot the film’s climax on an ‘apocalyptic grotto’ set, to be built on the Paseo de la Habana in Madrid’s eastern district of Chamartín. However, whilst scouting the neo-Gothic exterior of the Aldeadávila dam with his cinematographer, Federico G. Larraya, Mercero became fascinated by its foreboding netherworld of tunnels and dimly lit caves. Vázquez was equally impressed, declaring the location to be a suitably “devastating end…A finale that the spectator does not want to see or want to know” 39 – and so the stage was set for the protagonist’s last few minutes on film.

The penultimate scene, in which the man in the phone box is carried away by a crane, was shot inside the dam’s turbine room; a vast chamber, eerily reminiscent of a Bond villain’s secret lair. As Vázquez would later recall, this marked the one point during the entire shoot that caused him to fear for his safety. “They hung me from a crane and I said to myself ‘Oh Mother, I hope the floor of the cabin can support my weight. I don’t want to fall out, or for the crane to slip and drop me.’” 40Ever the professional, Vázquez drew on that fear to drive his performance and so make his character’s terrifying end all the more convincing for the viewer. He succeeded admirably.

Reception, Reaction and Controversy

If it hadn’t been for Mercero receiving the International Critics’ Award at the 1972 Monte Carlo Festival of Television, La cabina might never have been seen by Spanish TV viewers. Was Mercero’s strange little film symbolically criticising the Franco regime, as some at TVE feared, or was it just a bizarre fantasy, as Mercero claimed? Whilst the TVE executives awaited a ministerial decision, the transmission date was suspended, but with the Spanish press lauding Mercero’s success in Monte Carlo and the additional lure of lucrative foreign sales to come for TVE, the balance quickly tipped in Mercero’s favour. La cabina was officially approved, on the condition that one very brief scene was cut because it allegedly showed ministry property. It didn’t. Mercero’s camera merely followed the flatbed as it passed the frontage of an underground railway station – Nuevos Ministerios (New Ministry). Nevertheless, the offending scene met the cutting room floor, and on the 13th of December 1972, at 10pm, La cabina finally aired, on TVE’s LA1 channel.

That night Spaniards went to bed unsure about what they had just watched. Over the following days and weeks the film became a hot topic for discussion in homes, workplaces and bars, although many found the story confusing, even disturbing. As curiosity about a hidden message began to grow, La cabina was released in America, where it gained critical acclaim, leading to Mercero’s Emmy (the first ever awarded to a Spanish film director). Whilst there would be further awards for the director, lead actor and film, a legal problem suddenly threatened to mar Mercero’s continuing success. The German composer, Carl Orff 41 sued Mercero for the unauthorised use of a cantata from his operetta, Trionfo di Afrodite. 42 Apparently Mercero had simply ‘forgotten’ to approach Orff for permission. To avoid a scandal the issue was resolved with an out of court settlement after Orff met Mercero privately, viewed La cabina, then subsequently approved the use of his music.

Meanwhile, controversy of a far stranger kind had been brewing on the streets of Madrid, for just as Alfred Hitchcock had transformed a shower into a symbol of terror in his infamous Psycho (1960), so Mercero achieved the same result with the humble Spanish telephone box. Rumours about Madridilians becoming trapped inside phone boxes began to circulate, birthing an urban legend about kidnappings by a shadowy agency and causing those of a more suspicious nature to ensure phone box doors remained firmly open during calls. Perhaps fearing this rumour would affect its share price, the response from Telefónica was intriguing, to say the least. Putting a spin on the paranoia of the moment, it re-engaged Vázquez for a new Las matildes advert, 43 in which he parodied his iconic role in La cabina.

So, who’s afraid of the big bad phone box? With 21st century hindsight, it’s tempting to laugh at what we perceive as ignorant, superstitious behaviour, yet even in this age of social media, urban legends continue to abound, frequently tweeted and shared without fact checking first. The point being that such tales become, by definition, a form of modern folklore, effectively giving voice to primal human fears. Therefore it’s important to place this seemingly irrational fear of Spanish phone boxes in its proper historical context. In the earlier, more brutal years of Franco’s rule, hundreds of thousands of Spaniards became Los desaparecidos (the disappeared) during purges of political opponents and alleged dissenters. So it’s possible that La cabina resurrected very real, disturbing memories (especially amongst older Spaniards), which found unconscious expression through this strange phobia.

In a lighter vein, despite exhaustive research, not a single authenticated account of anyone, anywhere in Spain ever having become ensnared by a telephone box has been found, although it’s curious to note that those few Madrid phone boxes fitted with internal latches underwent ‘routine maintenance’ before the international release of La cabina, during which the latches were discreetly removed. So it’s not surprising that these ‘upgrades’, coupled with the general phone box paranoia, actually helped cement the film’s burgeoning cult status abroad, even leading to incidents of strange graffiti in the UK. Following the BBC2 Television release, on the 25th July 1981, black silhouettes of desperate outstretched hands mysteriously appeared in red telephone boxes around London and elsewhere.

Here, the tale might have ended, except that in this new millennium the iconic ‘man trapped in a telephone box’ meme has reappeared – in Ireland. It seems the grey man stubbornly refuses to die!

Yet More Controversy!

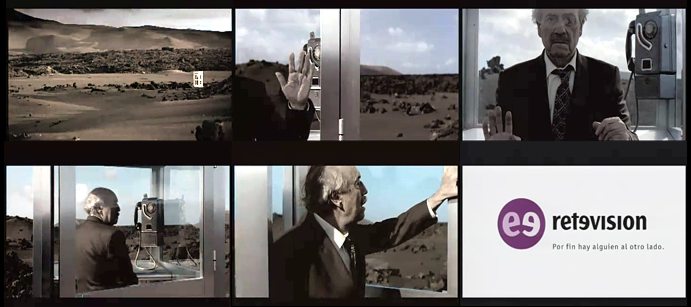

Twenty six years after the release of La cabina, in 1998, the Spanish advertising agency Tiempo BBDO was commissioned to announce the launch of a new telecom company, Retevisión – marking the end of Telefónica’s monopoly. The agency engaged Vázquez (then seventy-six) to step into a telephone box and duplicate his grey man role. Only this time the phone box door magically opened as an instrumental version of The Proclaimers: I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles) 44 symbolically freed the man to enjoy a new lease of life, presumably with Retevisión as his telecom provider. How liberating!

Upon seeing the advert, Mercero was furious! Interviewed by the Spanish daily, El País, Mercero said:

“It’s terrible that they use an idea of yours without asking your permission…On top of that, a lot of people think that I’m the author of the ad and I’m covering myself with advertising.” 45

Some might say this response was a touch hypocritical, coming from a man who may have been influenced by that scene from The President’s Analyst, but had certainly used Orff’s work without permission. All the same, accusations of plagiarism were laid against Tiempo BBDO, which retaliated with a statement to the effect that “A [phone] booth and José Luis López Vázquez do not belong to Mercero, or anyone.” 46 Mercero’s response was “My lawyer will decide.” 47 Mirroring the Orff v Mercero case, the issue was resolved out of court (yet again) with Tiempo BBDO acknowledging that its advert was indeed based on La cabina.

Parodies and Homages

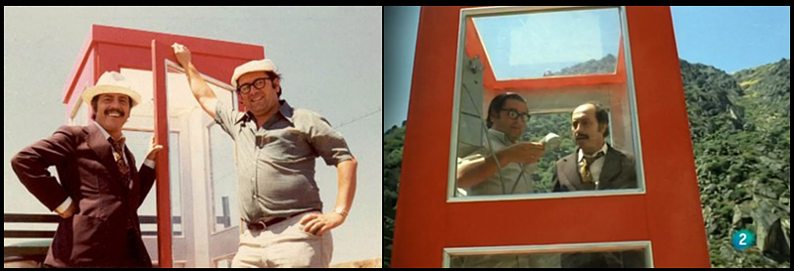

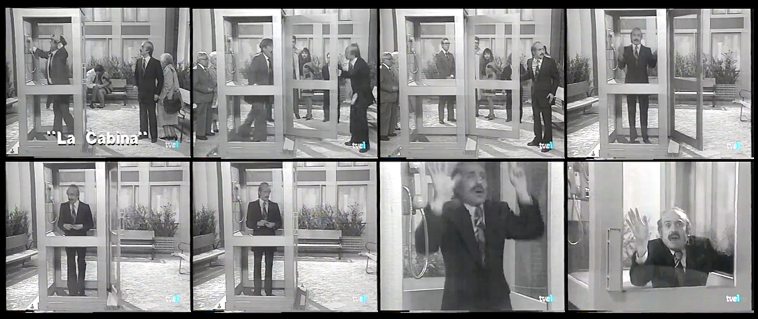

Coincidentally, that very same year La cabina was parodied by the Spanish comic duo, Juan Muñoz and José Mota, otherwise known as Cruz y Raya (Cross and Stripe). They had a highly successful series that ran from 1987 to 2004 – and little was sacrosanct in their eyes. The sketch, titled La Cabina, 48 appeared in RTVE’s (previously TVE) This is not the Friday Programme and thoroughly lampooned Vázquez’ iconic role. By all contemporary accounts, he enjoyed it!

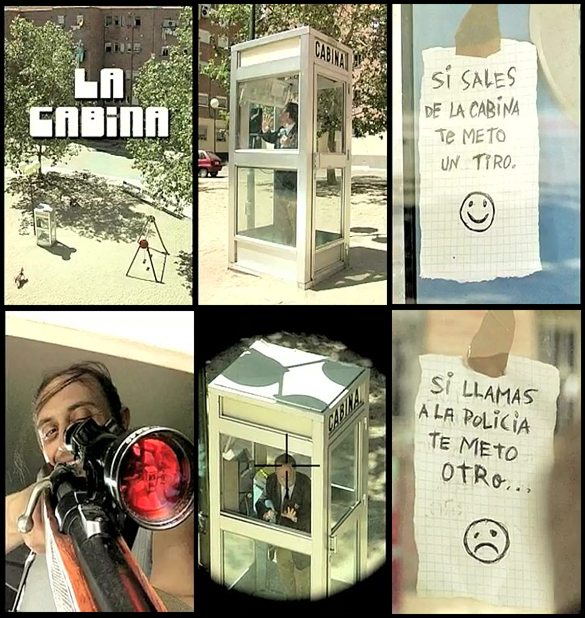

In 2005, the film maker Javier Fesser, 49 founder of the Jameson Notodofilmfest, 50 entered a short and very dark comedy-drama into that year’s festival, titled LA CABinA. 51 An obvious homage to the original, it featured a middle-aged man entering a phone box and finding a message stuck to the glass pane: ‘If you leave the cabin, I’ll shoot you.’ – with a little smiley face added for good measure. Another message stated ‘If you call the police, I’ll shoot you again’ – with a little sad face added as a warning. Meanwhile, in an apartment overlooking the scene, a dishevelled young man with a hunting rifle and ‘issues’ has an itchy trigger finger. Not a good combination!

2009 saw Mercero’s film briefly spoofed by the Spanish screenwriter and director, David Díaz, 52 in his seven minute comedy, Españolada a la plancha (Typical Spanish Platter). Also in 2009, the Madrid based rap band, La excepción que confirma la regla (The Exception that Proves the Rule) 53 paid homage to Mercero and La cabina in its video, La verdad mas verdadera (The Truest Truth). 54 A short, two-part film detailing the making of this video is available on You Tube. 55

Charlie Brooker, creator of the Black Mirror anthology, stated in a Spanish newspaper interview 56 that La cabina was one his favourite films. So it was probably inevitable that he would reference it at some point, which he did during the final scenes of an episode from Season Two of Black Mirror, titled White Bear (2013). Also in 2013, a young Spanish artist, Eva Marinac chose to depict Vázquez in his phone box, in clay. She stated, “I…have a special affection for him. I think he was an actor who was worth as much in comedy as in the most dramatic roles.” 57 Another artist, Jorge Itachi even went so far as to recreate the iconic phone box in miniature – complete with a miniature phone, but alas, minus a miniature Vázquez. 58

One of the strangest homages was paid by the Spanish painter and sculptor, Enrique Tenreiro. In 2014, as part of the Agra Directo festival in Coruña, Galacia (NW Spain), he began by distributing fake bank notes in the street, then locked himself inside a glass refrigeration unit 59 and mimicked Vázquez’ grey man – much to the amusement of locals and visitors alike.

On a more serious note, La cabina also inspired an anti-drugs campaign, run by the Dirección General de Tráfico (DGT), an autonomous government department responsible for the Spanish road network. In 2014 DGT released a short, public awareness video titled Saca tus drogas de la circulación (Take your drugs out of circulation) 60 in which a man, high on cocaine, is completely unaware that he’s been involved in a fatal road accident – until he realises that he’s permanently trapped in his car, alongside other vehicles with occupants in the same situation. The film is surreal, yet succinctly makes its point.

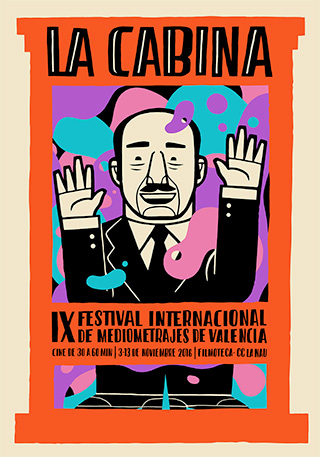

Stepping back a few years to 2008, a new film festival was launched in Spain. The La Cabina: Festival Internacional de Mediometrajes (International Medium Length film festival) 61 clearly took its name from Mercero’s short film, aiming to showcase work of 30-60 minutes in length that has a ‘defined statement of purpose: originality, exclusivity, innovation, culture…an international spirit and attention to design.’ 62 Held in the city of València (on the East coast), the festival ran for just five days in its first year although by 2010 that had been extended to a ten-day run. Now regarded as one of the most prestigious medium-length film festivals in Europe, it has recently attracted entrants from as far away as Israel, America, Serbia and South Korea. The spirit of the original La cabina lives on in a new generation of film makers.

One Man’s Initiative

Shortly after Mercero’s death, the Spanish screenwriter and one time Chamberí resident, David Linares launched an online campaign to erect a replica of the infamous red telephone box as near as possible to the original filming location. 63 He began with an open petition on change.org, then the campaign quickly spread to social media. With the hashtag #UnaCabinaParaMercero and the support of Mercero’s family and friends, the Spanish Academy of Motion Pictures and Arts and the Telefónica Foundation, Linares gathered thousands of signatures. The Municipal Board of Chamberí joined the initiative and when presented to the Madrid City Council, it was unanimously approved.

On the 24th of July 2018, the council met in a plenary session, during which the councillor for Chamberí and Carabanchel districts, Esther Gómez assured all those present that “The citizens’ proposal will be a pleasure to carry out. We are going to look for the best possible site to…develop this initiative.” 64 However, since the original plaza is privately owned and presumably the residents wouldn’t welcome hoards of Spanish horror film buffs peering through the railings (which is slightly ironic, considering the circus like plaza scenes in La cabina) an alternate site had to be found. Consequently, in March of 2019, in accordance with Linares’ suggestion, the Plaza del Conde del Valle de Suchil was selected, just 300 metres from the original location. 65 All that remains now is to await the return of a cultural icon to the streets of Madrid.

So, what began as a surreal joke about an ordinary man in an absurd situation is now to become enshrined as a national monument. Perhaps the last laugh really is with Mercero.

And Finally…

When a controversial film as rich in symbolism as La cabina gains wider attention, the search for a hidden message inevitably leads to speculation, theorising and even the projection of various ideologies onto the source material.

For example: L’Humanité, the former French communist newspaper, at the time declared La cabina to be the ‘gravest criticism of the Franco regime’, an opinion still echoed amongst viewers’ comments and reviews on the Internet Movie Database (IMDB), whilst the telephone box itself has also been interpreted as a symbolic Procrustean bed (an arbitrary standard to which all must conform). Bizarrely, some viewers in the 1970s considered the film a metaphor for an alien invasion, 66 whilst religiously inclined viewers instead saw the plaza scenes in particular as a metaphor for Man’s expulsion from the garden of Eden. Alternatively, from a modern-day perspective, the tale has been said to highlight the loss of individual liberty in a world increasingly subservient to corporate interests – hence the anonymous phone company. Poetically speaking, La cabina may be an interpretation of William Shakespeare’s The Seven Ages of Man, 67 although the Spanish psychologist, José Antonio García Higuera saw the telephone box as representing “A cave from which we can leave, but which we do not want to out of fear of the outside.” 68

In the midst of publicity surrounding the film’s international release, Mercero repeatedly dismissed the Franco metaphor. For instance, when replying to questions put to him by a journalist from the now defunct Terror Fantastic magazine, he stated:

“José Luis Garci…and I, recognised that when we wrote the script, we were closer to the world of science fiction and terror, than any political theme…We also realised that our story had many readings and that that was its richness and complexity…I would say then, that La cabina is a parable open to all kinds of interpretations and according to the sensitivity, culture and formation of each one, it will be interpreted in a different way, and those multiple interpretations will always be valid.” 69

Make of it what thou wilt, seems to be the essence of that statement. More recently, in 2009 (the same year that Vázquez died and Mercero was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s) Mercero was interviewed by RTVE and he made a statement that seemed to finally reveal what personal message he took from La cabina.

“All human beings have boxes that we have to get rid of. There are boxes of the moral type, there are boxes of the educational type, there are boxes of the mental type; economic boxes that imprison us and I believe…that life is a continuous quest for freedom from each one of these boxes. In order to be free, spontaneous and happy, each person has to see which box imprisons him…and try to free himself…that is our destiny.” 70

Alas, the grey man failed to gain his freedom, as did his creator, who became trapped within the debilitating mental confines of his own prison. However, in this writer’s opinion, Mercero’s last revelation is the real message of La cabina and, as such, it is just as relevant today as it’s always been.

Works Cited

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Franco ↩

- Antonio Mercero.https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0580318/Also see: http://www.cineyteatro.es/portal/DETALLEPERFILES/tabid/64/xmmid/394/xmid/2554/xmview/2/Default.aspx?bus=ANTONIO%20MERCERO (Spanish language) and https://www.antoniomercero.eus/en (English language) ↩

- La cabina. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2NKRNpn-1ek. A better quality version is available to download, for free, at http://rarelust.com/the-telephone-box-1972/ ↩

- La oveja negara. https://www.antoniomercero.eus/en/denbora-lerroa/cinema/la-oveja-negra ↩

- Lección de arte. https://www.antoniomercero.eus/en/denbora-lerroa/cinema/leccion-de-arte ↩

- https://www.antoniomercero.eus/en/denbora-lerroa/television/fiesta ↩

- Crónicas de un pueblo. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0211143/ ↩

- La guerra de papá. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0076116/ ↩

- La hora de los valientes. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0182236/ ↩

- Verano azul. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0077094/ Also see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verano_azul ↩

- Farmacia de guardia. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0098794/ ↩

- Planta 4ª. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0319917/ ↩

- ¿Y tú quién eres?. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0829326/ ↩

- https://www.antoniomercero.eus/en/bizitza-pertsonala ↩

- José Luis Garci. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0305054/ ↩

- Horacio Valcárcel. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0883553/ ↩

- Gutiérrez, Marisa. Extract from ‘Garci-Entrevistas’ (Garci. Interviews). 2010. Page 10. See:https://www.scribd.com/document/379324854/Garci-Entrevistas-Jose-Luis-Garci (Spanish Language) ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Jos%C3%A9_Plans ↩

- Higginbotham, Virginia. Spanish Film Under Franco. Texas: University of Texas Press.1988. ISBN-10: 0292776039. ISBN-13: 978-0292776036 ↩

- La gioconda está triste (The Mona Lisa is Sad) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0255192/ ↩

- Interview with José Luis Garci. ‘La Cabina de Mercero’.2011. RTVE2. 04.50-04.52 minutes. See:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXEbM6Uqhjk (Spanish Language) ↩

- https://www.ukessays.com/essays/film-studies/spanish-cinema-during-the-dictatorship-film-studies-essay.php. Also see: Peré Adán, José. Cine y sociedad, prácticas de ciencias sociales. Ediciones Internacionales Universitarias. Madrid. 2004. Page 119.(Spanish Language) ↩

- The President’s Analyst (1967). Paramount Pictures. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0062153/ ↩

- Publicidad años 50 – Las famosas ‘Matildes’. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G3cc4RUBoYE. 01:24 – 01:44 minutes. (Spanish Language) ↩

- http://todofondosdeinversion.com/las-matildes-historia-de-las-acciones-de-telefonica/ (Spanish Language) ↩

- José Luis López Vázquez. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0007023/ ↩

- Marcello Mastroianni. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0000052 ↩

- Vittorio Gassman. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0002094 ↩

- Mi querida señorita. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0067425/ ↩

- RTVE. La cabina. Presentation by Mercero and López Vázquez. See: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/television/mercero-lopez-vazquez-presentan-cabina/393271/ (2:23-3:00 minutes)(Spanish Language) ↩

- Pedro Lazaga. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0002815/ ↩

- El vikingo. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0069462/ ↩

- RTVE. La cabina. Presentation by Mercero and López Vázquez. See: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/television/mercero-lopez-vazquez-presentan-cabina/393271/ (3:20-3:54 minutes) (Spanish Language) ↩

- Agustín González. .https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0328020/ ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madame_Defarge ↩

- Pablo Serrano Aguilar. Westerdahl, Eduardo. La escultura de Pablo Serrano. Ediciones Polígrafa. Barcelona. 1977. ISBN 8434302616 9788434302617 (Spanish Language) ↩

- http://marefilms.com/la-cabina-6/ (paragraph 24)(Spanish language) ↩

- Javier Tolentino. http://blog.rtve.es/septimovicio/ ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Ibid ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Orff ↩

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trionfo_di_Afrodite ↩

- Telefónica’s parody of La cabina. 50 años de TVE – Antonio Mercero. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6HujJmwxXGo. 01:45-01:57 Minutes. (Spanish language) ↩

- The Proclaimers: I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbNlMtqrYS0 ↩

- https://elpais.com/diario/1998/01/14/sociedad/884732411_850215.html (Spanish language) ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Ibid ↩

- Cruz y Raya. La cabina parody.1998.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yrlkG55JtGc ↩

- Javier Fesser. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0275250/ ↩

- http://www.jamesonnotodofilmfest.com/ ↩

- LA CABinA.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zNFm39yyxZQ ↩

- David Díaz. https://www.imdb.com/name/nm3533255/ ↩

- La excepción que confirma la regla.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Excepci%C3%B3n ↩

- La verdad mas verdadera. https://vimeo.com/3841531 ↩

- The making of ‘La verdad mas verdadera’. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HHuZPUQrrr8 ↩

- Brooker comments on La cabina and White Bear. https://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2013/03/18/television/1363611580.html (Spanish language) ↩

- Eva Marinac. http://artesaniaconmanoypincel.blogspot.com/2013/06/jose-luis-lopez-vazquez-en-la-cabina.html ↩

- Jorge Itachi miniature phone box. http://www.mundodvd.com/edicion-numerada-y-limitada-de-la-cabina-metacrilato-mercero-1972-a-127439/ ↩

- Enrique Tenreiro’s street performance: https://www.lavozdegalicia.es/noticia/coruna/2014/10/25/enrique-tenreiro-mete-dentro-nevera-plena-calle-barcelona/0003_20141020141025174441356.htm ↩

- Take your drugs out of circulation. Short film by DGT. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5J1qo2Sr8U ↩

- La Cabina: International Medium Length Film Festival. https://lacabina.es/?lang=en ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- http://cinemania.elmundo.es/noticias/una-peticion-de-change-org-busca-instalar-la-cabina-de-mercero-en-madrid/ ↩

- Esther Gómez: la cabina de Antonio Mercero es un regalo para Chamberí. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Up2pF_ZiYKc. 01:30-01:38 minutes (Spanish language) ↩

- https://somoschamberi.eldiario.es/monumento-cabina-mercero-conde-valle-suchil/ ↩

- Juan Carlos Ortega (Narrator). La Cabina de Mercero. La mitad invisible. 2011. RTVE2. 08:32-08:34 minutes. See:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pXEbM6Uqhjk (Spanish Language) ↩

- As You Like It. Act II, Scene VII. Jacques’ speech to the Old Duke. ↩

- José Antonio García Higuera.http://www.rtve.es/television/20111005/cabina-proximo-estreno-mitada-invisible/466296.shtml (Spanish Language) ↩

- An interview with Pedro Yoldi. Terror Fantastic. 16th of January 1973. http://www.thecult.es/Cine-clasico/la-cabina-antonio-mercero-1972.html (Spanish Language) ↩

- RTVE: La cabina. Complete film with presentation by Mercero and López Vázquez. 27th of January, 2009. http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/television/mercero-lopez-vazquez-presentan-cabina/393271/ (08:51-09:22 minutes) (Spanish language) ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thank you for the writeup. One of my many takes on this film is that the suited man in the telephone box represents how one may be trapped by social trappings. He looks a man of some social standing. I note that the child, his son, escapes the trap, maybe representing the idea that children still retain freedom of thought. We note that he passes a dead child (death of freedom). Also he passes the clown and dwarf and circus folk. They to me represented those on the outside of society that retain their freedom. They look at him from behind a wall with a distant quizzical look.

The great machine of society robs man of volition.

Teresa. Thanks for the comments. Yes, I did find it interesting how the grey man’s son wasn’t trapped by the phone box and your suggestion about children still retaining freedom of thought has merit – but, did you also notice that the son didn’t lift the receiver? It was only when the grey man did so that the trap was sprung. I had considered, in an earlier draft, that perhaps the phone box represented simple temptation. It’s bright red, shiny and new! With regard to the clown and dwarf etc, it’s interesting that these are figures that are used to being laughed at, and yet they were the only characters who didn’t make fun of the grey man. It was as if they sympathised with his predicament, which made me wonder just how many flatbeds they’d seen pass by with a man in a phone box.

There’s a fascinating and very in-depth analysis written by the Spanish political activist, Marisa Domenech, you may like to look out for. I found it a while back. I’d give you the link, but at the moment I’m using a friend’s laptop and I’m not at home, so I don’t have access to my research files. Anyway, it’s well worth reading.

It’s about appreciation the simple things. U see how he realizes everything he took for granted as he is is driven out to his end. Masterpiece.

Man Fiore. So true. That scene when he takes out his wallet and looks at the photo of his wife and son is heartbreaking. It’s one of those small moments that we can all relate to

That ending was proper shocking back then.

Kira. And it still is! I was 20 when I first watched it (on British TV) and it haunted me for weeks. I must confess that some of those black silhouettes of desperate outstretched hands that appeared on London phone boxes were my doing…and a few friends as well.

I wonder what Stephen King would think of this…

h0mer. That’s an interesting idea. Mind you, I bet if Stephen King had made La cabina, he would have had blood seeping out of the box at the climax and the clown would have had a creepy laugh.

Great article. AND thank God phone booths no longer exist!

Anthony. Thank you for the praise. I only used about 40% of the material I collected during my research. My first draft had a very lengthy analysis, which I decided to cut as I’d even gone so far as to analyse the pattern on the grey man’s tie!

Well, phone booths as such may have disappeared, but how many people are ‘trapped’ by their mobiles/cell phones? That’s why I think Mercero’s last ‘revelation’ is still relevant today. Swap phone booths for mobiles and kidnapping for the theft of our personal information – and the song remains the same.

I spent some time in Spain last year and I was shocked to discover that many older Spaniards are still very placid, still very unquestioning of authority.

Reg-MAN. Yes, that is a sad fact. I find it all the more shocking when you consider just how many personal liberties Franco destroyed.

An informative exposé on a cultural landmark, and one I had no prior knowledge one! It always amazes me how media made years ago can be ahead of a time due many years after its zeitgeist.

Certainly, my view of the film was a surrealist critique of (then) contemporary dehumanization that comes with modern architecture and legibility. Another filmmaker who comes to mind in that regard is Jacques Tati, whose “Playtime” quietly asserts how impractical a “modern” city is for its people. Though “Playtime” is comic, and “La Cabina” is surreal horror, your mention of the “mime” qualities of Vázquez made the similarities jump out for me.

The cultural significance of a man being abducted by a telephone booth in relation to prior political “disappearances” stuck out for me.

I appreciate your article on this fascinating piece.

James Polk. Thank you for your appreciation. I think Mercero was certainly sailing very close to the wind when he and Garci scripted La cabina. There was a lot they could have said, but didn’t – leaving it up to the personal interpretation of the individual viewer. And that, in my opinion, is the mark of great scriptwriting and excellent direction. It’s interesting you mention Tati. He’s on my ‘I must write an article about him’ list.

The cultural significance of a man being abducted by a telephone booth in relation to prior political “disappearances” stuck out for me.

eliot092. Thanks. Sorry, I thought this was a repeat of James Polk’s comment, that’s why I missed it earlier.

This was very interesting to read. You did a fantastic job with researching this topic, and it’s very well-written. It was intriguing to learn that such an early film sparked iconic scenes such as in the Matrix. Thank you for sharing!

M.L.Flood. Thanks for the feedback. It was a toughie to research. I even went as far as to contact a Spanish film location company to ensure I had the details correct. La cabina has been referenced in passing so many times since its release. I only included a fraction of what I found. In my opinion La cabina does owe a lot to that scene from The President’s Analyst, though I can’t prove he ever saw it. Same goes for that TV advert. I think Mercero was a bit of a rascal when it came to (not) acknowledging influences on the making of La cabina. Later in life he did make a follow-up of sorts, only this time with a man becoming swallowed by a TV set, but it failed to make the same impact. You can’t improve on perfection! 🙂

I have watched thousands of movies and shorts and this is one of those that still stands fresh in my memory, mostly because I watched it when I was a teen, and I found it utterly cool and utterly disturbing.

Kunkel. Yes, it’s one of those films that stays with you. I love the notion that so many people can watch it and interpret the story in a different way. Here we all are, 47 years later, still discussing La cabina. Thanks for your feedback.

I love this film and have traumatised my children with it, just as I was traumatised by it so many years ago. I am saying that this is a good thing because anything that can have such a deep impact should be seen by anyone who wants to be really affected by great cinema.

Estell. Oh your poor children LOL. I can just imagine them thinking “Uho, she’s going to show us another of her weird films!” I hope they enjoyed it, or at least managed to survive their trauma. You’re right though, the impact of La cabina can still be detected today, albeit subtly.

Yup! I put it right up there with the first time I saw Star Wars, Close Encounters, Jurassic Park, Finding Nemo, Toy Story….OK, I could go on forever, you get the idea.

Glady. Oops, I almost missed your comment, tucked in beneath my reply to Estell. Yes, I agree. The first time I saw Star Wars was at the premiere in Hong Kong. Quite an experience, with people dressed as stormtroopers in the foyer and a huge replica of the Millennium Falcon launching itself from an equally huge painting on the wall. La cabina, on the other hand, crept up on me…like a thief in the night! I was drawn in and then pow! The climax! The image of the grey man’s hand sliding down the glass pane as he succumbed to the inevitable sent shivers up my spine. Utterly brilliant film making.

There is something about Spanish and Japanese movies, they seem to make the scariest and most disturbing movies. At least it was once that way. Time changed everything. Considering that most movies are more or less the same these days (rubbish or mediocre at best, being hard to find really good ones), I wonder if Spanish and Japanese cinema still have a word to say on that matter…

Belen. Is that a Spanish name, by chance? For me, one reason why Spanish and Japanese (and Korean) horror films stand well above the average Hollywood output is that the stories are often as much about the wronged spirit’s redemption as they are its revenge. Admittedly there are some directors who pander to ‘western’ tastes, but there are those who explore traditional psychological horror without resorting to buckets of blood. I’d recommend ‘Opiseu’ (Office, 2015), a Korean horror directed by Won Chan-hong. It’s one of those stories that doesn’t explain itself so leaves it up to the viewer to deduce what’s actually happening.

I hear the critique of the Franco regime in this but it just works on it’t face too.

caz. Well that’s the beauty of Mercero and Garci’s script writing. You can take from La cabina whatever you want. No one’s view is wrong. Thanks for your comment.

Remember seeing this the first time back in the late 1970s. It was way ahead of its time as a concept.

Rosa. Too true. I also think it’s a great example of what can be produced with a limited budget. Sometimes these restrictions can ironically bring out the best in a creative mind.

How cool to take a simple object and turn it’s perceived image completely on it’s head.

VENON. Well, that’s the mark of genius. I love the irony of the telephone box being a tool for communication and yet that is the one thing the grey man cannot use it for. He’s quite literally ‘cut off’ from the rest of the world.

I remember this in 1981 on BBC2 (but can’t recall it being shown again). Was the showing tied in to the ‘Horror/monster Double bills’ shown 70s to early80s? .most of these were Universal,Hammer, Corman etc films ,but also included Romeros ‘the Crazies’,’Bug’..

Blue. When I was doing the research for this article, I seem to recall that BBC2 originally showed La cabina as a filler, between two other programmes. I think there had been a last minute cancellation so this was used to plug the gap, so to speak. I didn’t make a note of the other programmes (sorry) as they weren’t relevant to the subject. Anyway, thanks for bringing up those old Hammer horrors. They were so bad they were damned good! Ah, fond memories. Cheers.

Your exactly correct Blue. I remember it was on with horror double bill on Bbc 2. I fell asleep before the end.

VBaum. Ah, thank you. I stand corrected.

This happened to me once. It’s okay though, they finally let me out.

Marry. LOL, and you never stepped into a telephone box again! Or at least not without jamming your foot in the door…just in case. Whilst I was doing my research I did come across a few stories of Spaniards finding shoes, books and even bricks wedged into the gap, but couldn’t track down one authenticated account. Just one would have been fun!

The use of a phone booth is significant. It could represent talking. People who talk against the government are isolated, publicly shamed, and finally, eliminated. And the man in the booth being punished so harshly while seeming to be an innocent, normal citizen could signify that it didn’t take much to be punished by said government. This film sticks in my head and even though I honestly found it somewhat narratively unfulfilling, it is still effective. I think it takes a bit long to get to the final reveal, but admittingly, the ending is powerful and haunting. This movie is a great primer for anyone thinking of writing a short story or making a short film. I love it when a story is able to make an everyday object absolutely terrifying, and this film did exactly that!

Noel. Hi, yes that’s an interesting interpretation. As I mentioned above to VENON, there is that wondeful irony of the box being a tool for communication and yet that was the one thing the grey man couldn’t use it for. So, literally, his ‘voice’ was silenced. Following your idea of the man being punished – that does fit in with the Kafkaesque style of La cabina, as we never find out anything about the grey man, other than he’s married with a son. Is he an office worker? Is he just another face in the crowd? He is, essentially, a cypher. I understand your concerns about the time it takes to get to the ‘reveal’, but that was actually what I liked about the middle section of the film. The viewer has no idea what’s going on and why the man is being driven around Madrid then out into the country. For me, that divorces the story from reality and we are simply taken along for the ride. We are as much a prisoner of the narrative as is the grey man. We simply have to wait it out. Anyway, thanks for your comments, I’m pleased the film made such an impact on you.

Try The Dictators Handbook, a PBS series, they have an episode on Franco. Just watched it and I remembered this short film. It is eye opening, Spain actually has the highest number of mass graves in the world after Cambodia, and all because of this man. Heartbreaking.

Ham. Hi and thanks for the contribution. Yes, I am aware of the PBS series you mentioned. During my research I read (and watched) a lot about Franco and learned more than I was ever taught in school. However, since much of what I read/viewed was not directly relevant to the subject I was researching, I avoided getting entangled in political analysis, prefering to leave it to the reader to interpret La cabina in whatever way he/she wished. You’re quite right though – Franco was a monster incarnate. If there’s any divine justice after death, then he’ll be getting his!

I saw this in the 70’s and it gave me nightmares… i was 6. great film.

Bok Kuntz. Blimey! At 6 years old I was still hiding behind the sofa and terrified of Daleks. I’m not surprised La cabina gave you nightmares.

I had never seen this before, thank you for introducing it to me. Very powerful.

Definitely an allegory on Spain’s government in mid 20th century. Where people would just “disappear” if they said something against the Status Quo. Interesting how the everyday people in the film saw this as something to laugh at and seemed not at all worried, “There are none so blind as those who will not see”. On the other hand those on the fringes of society, the Gypsy carnival players, are almost mournful when they see him as if they understand exactly what he feels or at least what might be waiting for him.

When I saw the other truck with the cabin I was like, “Oh, crap” this isn’t going to end well, at the beginning with the light hearted music you almost feel like laughing along with the mob that has come to witness someone else’s misfortune (social media today in many instances).

Oh and I found the chorus near the end very reminiscent of The Omen. Very creepy and almost Twilight Zoneian (if that’s a word).

Hilario. You’re very welcome. Did you follow the link to the free version at rarelust? It’s a better quality copy than the You Tube version. I liked your observation about the carnival players. I too wondered just how often they’d seen a flatbed pass by with a man in a box on the back. Interestingly, I did find a comment on IMDB, from a Spaniard who said that the way the grey man was laughed at in the plaza was typical of Spanish behaviour at the time. It was a case of ‘rather him than me’. That’s a good link you made to today’s social media – very much the modern day circus in many respects. ‘Zoneian’ – well if it wasn’t a word, it is now 🙂 Cheers for taking the time to comment. Much appreciated.

My mom told me about this film. Now that I’ve read your post, I MUST watch it.

kik, Yes! please do. Follow the link to rarelust, it’s a better quality version, although it’s one of those slow download links for non members. Worth it though.

Me and my brother watched this as kids in the late 70s and for many years we talked about how utterly disturbing this movie was. I just watched it again and it brought back horrible memories.

Devo. Ooops, sorry, didn’t mean to dredge up bad memories for you. Still, it just goes to show that the film as as potent today as it was back in the 70s. Thanks for your comment.

We can all relate to being trapped somewhere in life with seemingly no escape. This film gives no hope oh dear. It’s the phone booth of fate.

Hambooooook. LOL ‘The phone booth of fate’. Love it. Well, at least they’re a dying breed now. In London many of the old red phone boxes have been converted into books stalls, flower stalls, mini offices (really!), hairdressers and even a coffee shop! I’d love to be deliberately obtuse and buy one then turn it into a phone box!

I saw this in 1981 when I was 16/17 and while terrified loved it. I talked about it to people for years. I finally got a DVD of it about ten years ago but can’t bring myself to watch the end again…

Whiting. Go on, watch it to the end. I dare you! I love the part when his hand slides slowly down the glass pane.

I first saw this film on Channel Four in the UK in 1983. At the time, the channel found myself in its infancy.

Amelia. Yes, back then Channel Four actually tried to be a little different from the usual output of BBC and ITV. I remember it was quite experimental. Oh well, fond memories. It’s all the same these days. I haven’t had a TV in my home since 2005.

I did not see it until 82 it scared the crap of me.

iam. Thanks for the comment. One of the aspects that I still find chilling is how the anonymous telephone company men just go through the motions with no emotion at all. To them, this is just a job. It’s that cold indifference to suffering that hits home.

Freaked me out when I first watched this, I was only 10.

Franklin. You have a good point there. Even now I wouldn’t recommend the film for any child. I think a little emotional maturity is needed to appreciate La cabina, as well. Anyway, I hope it didn’t give you nightmares.

Pretty interesting and terrorising when you realise that this short film was shot produced by the public TV of a dictatorship that made disappear between 100k-200k people.

It’s not superficial, censorship didn’t notice that “La Cabina” was an allegory about Spain itself (even if it goes way more universal in its message). It’s a complete masterpiece and an essential piece to understand Spain’s cultural history of the last quarter of the XXth Century.

Quincy. Beautifully put and so succinct. Thank you. I agree with you regarding Spain’s cultural heritage. I just hope that new box doesn’t get vandalised.

I saw this film long time ago and never forget it, but I was always watching odd French films love them.

Ernesto Ade. Sounds like you and I have a similar interest in films. I grew up watching ‘foreign’ subtitled films. French, German, Spanish, Italian etc – and now Japanese, Korean, Thai, Taiwanese etc. I have more non-English language films in my collection than English language. I, like you, saw La cabina for the first time many years ago and never forgot it. It’s one of those films that can never be remade. A true classic.

Seriously errie short film. Probably best breakdown of the film I have ever read/seen. Great job.

Cristine. Thank you, Your praise is very much appreciated. In my first draft I had included a very in-depth analysis of the symbolism – such as the reference to the French revolution and Greek mythology, but then decided I’d better cut it, otherwise this article would have been a bit of a tome. There is so much more hidden beneath the surface!

This was really creative o love the slow dissent into darkness and how here was a lighthearted comical feel until the last few minutes, as if to say that things turn dark and deadly fast. What’s creepy is the feeling that nowhere is safe. This guy was surrounded by so many witnesses but still was hopeless. I like this because it so absurd it stretches the bounds of possibility.

YOSHI. Yes, I know what you mean. The opening music could almost have been written for a typical 70s comedy, though I did love that weird, discordant oboe that mournfully played from time to time. ‘I like this because it so absurd it stretches the bounds of possibility.’ Nice comment and bang on! That’s exactly what Mercero was good at achieving. Thank you very much for your comments.

No dripping blood, No imaginary creatures. No haunted house and spooky forest. Just an ordinary morning in and ordinary town full of ordinary people. And there is no answer to the question ‘why?’

Kasi. Exactly! Less is more. It’s the horror of the absurdity that makes La cabina a masterpiece.

I watched it with my 10 year old daughter not knowing how it ended, gave her nightmares and even disturbed me, regret to this day allowing her to watch it.

Lebron. I’m so sorry to read that. Admittedly it is one of those films that even despite the lack of blood and gore is psychologically terrifying. I truly hope your daughter wasn’t too traumatised in the long run. It’s difficult to know quite how to explain La cabina to a child as even many adults found it disturbing.

I first saw this on British TV in 1981- it was only many years later (when I knew something of Spain’s recent history) I found it again that the allegorical theme was clear to me…

Mila. Thanks for your comments. Yes, there is an obvious, surface reading of La cabina and I’m not denying that has relevance to the overall tale, but as I mentioned to Cristine (above comment on 30th July), there is so much more hidden beneath the surface. La cabina works on many different levels. Spain during the mid to late seventies was rapidly modernising so many run-of-the-mill office jobs were disappearing. The grey man might just be one of those thrown onto the scrap heap. He’s become unemployable so there’s no need to keep him around. There’s also the subtle reference to the French revolution, in the two middle-aged ladies knitting on the bench. They reference Madame Defarge who, in turn, was a representation of the Greek Morai (the Fates), who would spin, measure and cut the chord of a person’s life, so determining how long that person would live. There’s also a passing reference to the Greek Goddess Circe’s man-beasts, whilst the circus metaphor is there in plain sight. The point being that Mercero and Garci crafted their story with such elegance that we could all find something different, something relevant to our own lives, in La cabina. Anyway, thanks for your input. It’s been a surprise for me to find that so many people remember La cabina. It definitely made its mark!

A superb and gripping little film. One of my favourites. Makes the clichéd mime artist in glass box a reality.

Blanch. Thanks for the comment. Yes, I agree with you – and that’s why I was delighted to find that ‘performance’ by Enrique Tenreiro ‘looking cool in his fridge’. Just perfect – a homage, a parody and a mime performance all in one.

Seems like there was a host of us that this movie affected whilst watching as a child. I suspect it speaks to a basic fear about being forgotten or neglected.

Reilly. Yes, you’re spot on with that observation. La cabina really does play to our most deep-seated fears. I think all of us would like to think that even in some small way, we’ve left our mark and we will be remembered.

If you see no other short film in your life, this is the one to see. Dark, Kafkaesque, Hitchcockian, a real pleasure to watch. And it should be mandatory to read this analysis afterwards.

Shah. Thank you for that incredibly generous response. I’m also delighted that you hold La cabina in such high esteem. I have, quite honestly, been so surprised by the overwhelming positive response. I never realised that La cabina had had such an impact on so many people here at the Artifice. Thank you once again.

Watched this short film as a child and it’s upsetting how everyone just laughs at him and the ending is very haunting.

Muoi. Thanks for your comments. Yes, even now it’s worth a nightmare or two. In fact the only people who don’t laugh at him are the clowns!

What a well-researched and interesting article – many thanks indeed. I saw the film for the first time about 40 years ago, and was quite haunted by it. By chance I found it again on YT a couple of days ago, and was not disappointed. Sure, it’s aged a little – but the craftsmanship of the cinematography and sheer creepiness of the ending remain as intact as ever. A great cautionary allegory for modern times. Thanks again.

Boris. Thank you. I’m pleased you found the article interesting. It seems that La cabina had a lasting effect on many people, far more than I realised. Your input in greatly appreciated.

Is there any information on the two pieces of music used (not the finale Orff pieces).

Chas. I haven’t been able to find any more information on the music used. I spent ages digging through RTVE archives and emailing bloggers etc, to try and find the answers for myself. I was particularly intrigued by that mournful piece (possibly played on an oboe) used when the grey man first realised he was stuck in the telephone box. Apologies for not being able to offer any answers. If, by any chance, you have better luck than I, please let me know.

No it’s fine and thanks for the response! For the record, the first piece in question occurs during the journey through the town. It’s even sync’d nicely to the moment he’s in traffic, thinks sees another trapped man, who of course walks out.

The second is soon after the ‘dwarf with the ship in a bottle’ scene, when he panics and his final journey begins.

Anyway, great article and much appreciated 🙂

Correction: not the ‘dwarf with the ship in a bottle’ scene, — but when the paisley tie guy pull sup next to him.

Does anyone have any knowledge of a possibly British remake of La Cabina?

I was very young when I saw it – or possibly dreamt it – but this Spanish version is not the version I remember. I swear I watched a more up to date version with a younger victim and a female in the other Telephone Box. I also had a more graphic lingering end.

Si. Thanks for the interesting comment. I did a great deal of research for this article, but haven’t come across any remakes, British or otherwise. That’s not to say there might not be one. After all Mercero attempted to revamp the same idea with a later short film – this time set inside a TV set. Maybe what you saw was an indy film or a student film? La cabina has certainly been spoofed, parodied and heavilly referenced many times. If you do manage to track down what you saw, then please let me know. Best of luck with your search.

This is such a great analysis, Amyus. Thank you for it. I found it through a reddit thread discussing the film, which I watched as a child in Poland. It scared me beyond belief, and for a very long time.