The Creative Industries in Bangladesh: The Case of Coke Studio Bangla’s “Deora”

In the conversations of global creative industries, very little to no research or information is available on the creative industries in Bangladesh. The big economies of North America and Europe dominate the conversations on creative industries worldwide. One can also argue that Bollywood of India shadows Bangladesh’s creative industries. The larger Indian entertainment industry has worldwide influence, and the cultural and linguistic similarities between India and Bangladesh may present Bangladeshi creative industries as insignificant compared to India. Even though both folk and urban creative industries have robustly continued for centuries in Bangladesh, producers and artists are not keen to present creative products to global audiences. The country’s target audience for creative productions has mostly been Bengali speakers.

However, some creative productions from Bangladesh have created ripple effects on global social media platforms. Coke Studio Bangla, the fusion music series featuring established and emerging artists and musicians, produces genre-bending performances that have gained popularity among music lovers around the world. “Deora,” the salad bowl of various Bangladeshi folk and choir-style music and performance, is one of the latest and the most popular creative productions of Coke Studio Bangla that not only deconstructed the concept of fusion music in South Asia but also made a unique mix of creative industries within one inclusive production.

Creative Industries in Bangladesh

Before discussing “Deora,” it is prudent to shed light on the concept of creative industries. Defining creative industries can be complicated as general definitions are limiting for creative practices in different cultures and communities. Creative industries as an academic discipline developed with the growth of entertainment industries. Terry Flew 1 explains that the formal inception of the concept of creative industries can be traced back to a pivotal decision made by the newly elected British Labour government in 1997, led by Tony Blair. This decision involved the establishment of a Creative Industry Task Force (CITF) as a central initiative within the newly formed Department of Culture, Media, and Sports (DCMS).

The CITF, created as part of this initiative, played a crucial role in shaping and promoting creative industries. It produced a mapping document that defined creative industries, describing them as activities rooted in individual creativity, skill, and talent, with the potential to generate jobs and wealth by creating and exploiting intellectual property.

This definition underscores the connection between creative industries and the personal qualities of creativity and skill. It also emphasizes the economic potential of creative industries by highlighting their ability to create employment opportunities and generate wealth through the development and utilization of intellectual property. The decision to establish the CITF and define creative industries in this way reflects a recognition of the economic and cultural importance of the creative sector.

Hartley et al. 2 state further that the definition provided by the Department of Culture, Media, and Sports (DCMS) encompassed 13 industry sectors. These sectors were advertising, architecture, art and antiques, computer games/leisure software, crafts, design, designer fashion, film and video, music, performing arts, publishing, software, and television and radio. According to Cheryl Thompson and Miranda Campbell, 3 creative industries, from their inception, are a blend of creative production specific to local contexts, non-commercial in nature, and culturally distinctive, alongside globally disseminated, commercially oriented products often driven by content-based creativity.

Such conceptualizations are applicable considering the creative industries in Bangladesh. Several years of my ethnomusicological research findings explain that folk music, literature, dance, theatre, performance, and diverse forms of mixed creative expression lay the foundation of creative industries in the country. These creative activities are aimed at the intellectual growth of communities exploring philosophy through performances. Such explorations of critical thoughts through creativity in communal spaces of rural Bangladesh were the primary sources of entertainment for people in the country. The early forms of these folk creative practices were non-commercial (similar to what Thompson and Campbell refer to) and community-focused. However, transactions between performers and audience-communities occurred at these creative sessions. Traditionally, communities provided goods and food items for performers and artists in exchange for their performances. According to Bilal Hossain, 4 both practitioner musicians who chose a spiritualist path and performer musicians who chose music and performance as livelihood were significant participants in the early forms of creative industries. The practitioner musicians were farmers or owned small businesses for livelihood. However, the performer musicians solely depended on the transactions with communities in exchange for their performances. Therefore, although the folk creative industries were non-commercial, the commercial approaches to creativity by performers were accepted then and are widely accepted now.

In Bangla or Bengali, the language of the majority in the country, the term creative industry is translated as srijonshil shilpo. In the etymological Sanskrit source of this word, as mentioned in Banerjee’s dictionary, 5 srijon means ‘to create’ and shil means ‘self’ or ‘selves.’ The Bangla word shilpo means both creative activity or expression and industry. Srijonshil shilpo is a profoundly philosophical and inclusive term that describes and glorifies all kinds of individual and collective creative acts contributing to the intellectual growth of a community. Duddu Shah (1841-1911), a folk spiritualist, musician, and philosopher in Bangladesh, composed several songs signifying the term srijon as a celebration of individual or collective imagination that creates and feeds people. 6 He specifies creative imagination as an enriching human quality that “feeds,” meaning it satisfies the core need of the human psyche to understand aesthetics and fulfills the necessities of household needs. Therefore, both economic and intellectual gains are embedded within the broader conceptualization of this term.

Some affluent intellectuals in the country see artistic and creative practices as sacred and cannot be performed for financial gains. Perhaps the influence of thoughts promoted by Modernism and Enlightenment in Europe on postcolonial Bangladesh motivates such notions among the educated elites. Creating a dichotomy between arts for celebrating aesthetics and arts for business can be problematic. This dichotomy may question the agency of marginalized communities in Bangladesh who practise creativity for livelihood. Therefore, such a dichotomous concept rarely exists among the country’s traditional performing arts, music and literature practitioners. Srijonshil shilpo celebrates all creative artists who produce art forms for their non-commercial spiritualist purposes and commercial performances.

In folkloric oral literature, songs, and narratives, the term srijonshil shilpo has been used for centuries in Bangladesh, establishing the agency of folk creative practices. The meaning of shiplo or industry here is broad because it includes the expansion of creative practices in multiple regions along with economic gain and diverse meaning-making. Finding an exact government document that explains creative industries as emerging and established industries in Bangladesh may take time; however, Khan 7 argues that some references must have been there in the government documents of the early 1970s after the independence of Bangladesh in 1971. Aroj Ali Matubbor (1900-1985), 8 a Bangladeshi “rationalist” philosopher, prophesied about folk creativity as srijonshil shilpo, explaining that this industry would bring economic benefits for marginalized Muslim and low-caste Hindu performers in the future. Entertainment Industries, such as Coke Studio Bangla, bring marginalized and relatively lesser-known musicians and performers in front of a global audience and guarantee the continuation of their spiritual and commercial artistic endeavours.

If we explore the question of what is included in creative industries in Bangladesh, we need to include all creative activity in mainstream media, social media, and all other forms of entertainment spaces (such as concerts and live events). People involved in both creative and administrative capacities with these creative activities are also part of creative industries. Therefore, not only radio, TV and films and associated singers, actors, and performers are part of creative industries, but content creators, such as Shams in Thoughts of Shams and podcaster and psychologist Yahia Amin in Perspective, are significant contributors to creative industries. People and creativity associated with entertainment, intellectual growth, and arts business are considered creative industries. Many of these creative industries are primarily based on live events, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and streaming services (also known as over-the-top media services) in the country.

“Deora”: An Inclusive Fusion

“Deora” is the most popular creative production of Coke Studio Bangla, the YouTube-based music series producing fusion. The song has received more than 50 million views so far and is gaining attention in the studies of musicology and creativity. With elements of Western music and Bangladeshi folk music depicted in the instruments, including the harmonium and one-string instrument of folk musicians khamak, this performance combines three primary genres of vocal music: shari gaan, adhunik gaan, and gospel choir. However, the foundation of this performance is the shari gaan, known as “Deora,” composed by Fazlu Mia from the village of Bangram in the district Sirajgonj (as reported in Shomoy TV). He composed this song to participate in boat races in his village with his boat named uronto bolaka (flying crane). In the fusion “Deora,” he also performs the shari gaan with his team, standing on a prop designed as a boat.

Image Source: Coke Studio Bangla Official Youtube Channel

Shari gaan, the genre of folk songs, is performed to energize an activity that needs a rhythm to avoid the boredom of repetition. Typically, boatmen sing these songs, creating a collaborative cadence to win the age-old tradition of nouka-baich or boat race in riverine Bangladesh. The first reference to shari gaan is discovered in the Padma Purana, authored by the medieval poet of Bengal, Vijayagupta (Hossain 2011). In this text of long epic poems, the term shari is used to denote music. As time progressed, the song gained popularity during rural boating competitions. Subsequently, farmers and labourers began incorporating this song into various agricultural activities such as ploughing, weeding, harvesting, and beating thatch, effectively easing their labour. Shari gaan has evolved beyond being just labour or work music; it is now regarded as a form of entertainment and a component of competitive sports, resonating deeply with the rural population of Bangladesh.

Shari gaan primarily involves male voices in ensemble rather than solo performances. The ensemble typically consists of a bayati, who sings the main song and directs the dohars, the group of support singers, intermittently. The dohars sing in unison as a chorus, allowing the bayati brief moments of rest.

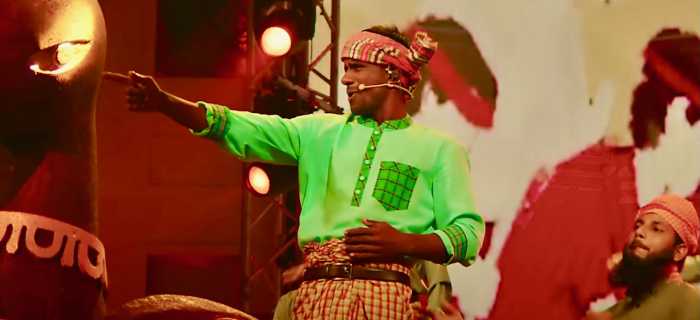

The fusion “Deora,” deconstructs the traditional masculine positionality of the bayati, who leads the song. A palakaar, the gender-fluid performer, takes that leading position and begins by singing the main song of the performance. Islam Uddin, an experienced palakaar in Bangladesh, has become famous by performing in “Deora” with his bright, colourful dress and the styles of palagaan.

Palagaan, originated in the district of Mymensingh (Hossain 2011), is a storytelling performance with songs, dances, and monologues where the leading artist or singer, the palakaar, performs as a man, woman, a non-binary person, an animal, an inanimate object or even as a paranormal being, based on a story’s need and progression. When a palakaar performs, the palakaar becomes the story, immersing in the context of the reality created on stage. The performer’s gender identity becomes irrelevant in most of these performances. Since Bangla has no gender-based pronouns, the songs and monologues in Bangla enhance diverse meaning-making creativity through gender-neutral identities.

Islam Uddin’s presence in the performing space of “Deora” incorporates components of palagaan in this fusion. When he begins to sing, he personifies a married rural woman having a playful conversation with her husband’s younger brother or “cousin-brother.” She calls this brother deora, which also becomes the title of this production. She takes the lead, replacing the male bayati, begins the main shari gaan, and allows other singers to perform their pieces. However, this three-minute and forty-seven-second performance is carefully crafted so no performer has a hierarchy over others.

Image Source: Coke Studio Bangla Official Youtube Channel

The erasure of hierarchy is unique in this performance space because this space mimics the mela, the place with festivities happening on both sides of the river during a boat race. Mela, a combination of various creative activities, games, and celebrations of regional cuisines, occurs in rural areas of Bangladesh. The sole purpose of mela is to bring people together to celebrate local creativity, a space where constructed social hierarchies do not exist. In an interview, Fazlu Mia alludes that he observes the surrounding festivities happening during a boat race, and people in those contexts become the subject matter of his songs. Mela brings different kinds of performers together in one space where hierarchies among performers are erased, and creative expressions complement each other.

Image Source: Bangladesh Post

Following the conventions of Mela, the performance space of “Deora” in Coke Studio Bangla creates a fusion festivity of Bangla music, where each musical form complements the other. Before Islam Uddin begins the main song, an Ode, in the style of adunik gaan, introduces the performance glorifying the patriotic identity of Bangladeshi citizens. Adhunik gaan, a vocal music genre, depicts themes of love, day-to-day struggles, patriotism, and contemporary societal issues and evolves with the changing nature of world music. Pritom Hasan, a famous musician, vocalist, music director, and producer in Bangladesh, is also the leading music composer and producer of “Deora.” He performs the Ode in the fusion. Ghaashphoring Choir, an emerging choir singing group in the country, added the element of a gospel choir in the performance. Armeen Musa, the director of this choir, explains to The Daily Star that the group sang and harmonized 15 layers of vocals in this performance. To enhance the “gospel vibe,” according to the suggestion by Pritom Hasan, the group added choreography typically seen in gospel choirs, involving clapping and dancing.

Image Source: Facebook Page of Armeen Musa

The performance space brings different stories through songs where one musician celebrates patriotism; one palakaar invites a relative to her house; one shari gaan singer and his group evoke the accomplishment of boat races in simple rural livelihood. A choir group harmonizes to bind these stories together. The stories and the music place themselves in balance as if each genre dignifies the other. At the same time, Shayan Chowdhury Arnob, a renowned musician in Bangladesh and the Season Producer and Curator of Coke Studio Bangla, explains in Deora: Behind the Magic that every musician performs authentically with his or her own unique styles that unify well with the collaborative performance.

Fusion in Bangladesh is a complicated genre of music because its growth is not linear. Much research needs to be done to identify what specific historical influences drive the contemporary growth of fusion music. Fusion music in South Asia originated during the British colonial era and continues to flourish in the post-colonial period. The dynamic between the colonizer and the colonized was inherently imbalanced. That imbalance continues in fusion music in Bangladesh, where Western genres of pop and rock gain prominence over Bangla music elements in many fusion productions. Arguably, The Beatles were the first known rock band that influenced the beginning and continuation of band music in the 1960s (Hossain 2011). Band music was one of the first music traditions that contextualized the formations of fusion music. Fusion is the music of the elites; English-educated middle and upper-middle class consume this music. The over-imposition of Western instruments and vocal music styles seems natural in most fusion compositions in the country.

However, Coke Studio Bangla, through the production of “Deora,” deconstructs this imbalance and fosters a balanced fusion where various Bangla music forms glorify each other, and even Western elements of music, such as the gospel choir and rock music on the guitar, complement the Bangla music. “Deora” becomes inclusive by including performances from various communities and making it popular throughout all social classes in the country. Pritom Hasan brought together artists from the core, the local performing spaces in different districts of the country. “Deora” exemplifies how fusion music, a significant part of creative industries, can advocate agency for creative communities.

Image Source: Coke Studio Bangla Official Youtube Channel

A Unique Mix of Creative Industries

Bangladesh is a growing economy, making frequent news for its GDP growth. Unfortunately, creative industries are not considered significant to the country’s economy. Arts is considered only for entertainment; the business of arts rarely seems a viable option for many creative communities. However, creative industries can create opportunities for both privileged and marginalized communities. Business of arts transforms performance spaces where communities can nurture empathy, establishing financial and spiritual growth. Peter Campbell 9 emphasizes the importance of creativity in the economy and explains that creativity may be of some importance now, but it will be even more critical in future, and so those who do not take preparatory action will, in an era of global competition, be left behind.

Coke Studio Bangla and its productions signal that future by bringing creative professionals together and developing a new economic and empathetic network among established and emerging artists from different regions of Bangladesh. “Deora” not only celebrates musicians but brings the artistry of set directors, fashion designers, art designers, and many more creatives listed in the fusion’s YouTube description. In Deora: Behind the Magic, Krishnendu Chattopadhyay (director) also signifies how the traditional mela inspired the colourful set, harmonizing with the colourful outfit of Islam Uddin Palakar. Art director Razim Ahmed focused on two motifs: boitha, the paddle of the boat and gamcha, the soft, colourful, and checkered cloth to wipe the upper part of the body. Boatmen wear gamcha on their heads while paddling the boat; therefore, these two motifs tune skillfully with the set. The art design team also crafted a chandelier with gamcha for the set. Costume designer Disha explains the depiction of folkloric art on Pritom Hasan’s shoes, jacket, and the hoddies of Ghaashphoring Choir singers.

The creative harmony that flows through the crafts and expressions of these artists forms managerial networks and economic patterns that are often unnoticed. Creative Industries are those rare industries where spirituality, affective experience, passion, human bonding, creativity, and profit unite and glorify each other. Bangladesh may need more innovative platforms like Coke Studio Bangla to diversify the future economy through creative industries.

Notes

- For more clarity, readers should watch “Deora” and turn the close caption option on to enable the subtitles.

- This is an independent study of “Deora.” The author has no affiliation with Coke Studio Bangla.

Works Cited

- Flew, Terry. The Creative Industries: Culture and Policy. Los Angeles: Sage. 2012. print. ↩

- Hartley, J., Potts, J., Cunningham, S., Flew, T., Keane, M., & Banks, J. Key Concepts in Creative Industries (1st ed.). Los Angeles: Sage. 2012. print. ↩

- Thompson, C. and Campbell, M. Introduction to Creative Industries in Canada, edited by Cheryl Thompson and Miranda Campbell. Toronto: Canadian Scholars, 1-13. 2022. print. ↩

- Hossain, Bilal. bangladesher gaaner itihash [A History of the Songs in Bangladesh]. Dhaka: Nabodoot Prokashoni. 2011. print. ↩

- Banerjee, Ashoke Kumar. shangskrit to bangla ovidhaan [Sanskrit to Bangla Dictionary]. Kolkata: Shadesh Prakashani. 2001. print. ↩

- Shah, Duddu. baul fakir padaboli: duddu shah [Songs and Verses of Baul Poets and Spiritualists: Duddu Shah], edited by Sumonkumar Dash. Dhaka: Annesha Prokashon. 2017. print. ↩

- Khan, Shamsuzzaman. Prelude to Folklore in the Urban Context, eds. Shamsuzzaman Khan, Firoz Mahmud, and Shahida Khatun. Dhaka: Bangla Academy Press, 9-10. 2016. print. ↩

- Matubbor, Aroj A. 1977. srishtir rohossho [The Mystery of Creation]. Dhaka: Pathak Shamabesh. 1977. Web. 15 Nov. 2023. ↩

- Campbell, Peter. Persistent Creativity. [edition unavailable]. Springer International Publishing, 2018. Web. 15 Nov. 2023. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.