Feminism in the Postmodern Era: A Study of Jenny Holzer’s Selected Works

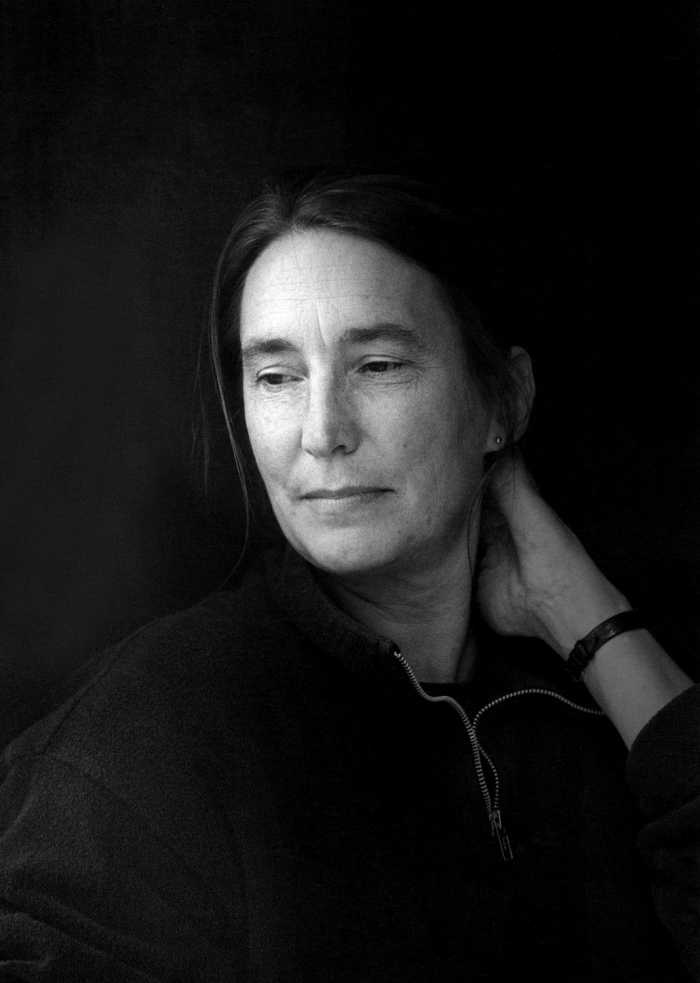

Second-wave feminism in the 1970s nurtured a generation of visual artists who unashamedly voiced out their concerns over intimate issues of women in private and public spheres. They boldly proclaimed “the personal is political,” while unflinchingly demanding equal rights between women and men. Primarily known for her large-scale public works, conceptualist artist Jenny Holzer is among this group who chose to express creative ideas through displays of aphorisms in public spheres: at schools, by roadsides, on building walls, and many more. With the help of flashy L.E.D. signboards, signs, and occasionally plain papers, Holzer’s works remain memorable to the mass to this date. This article seeks to explore how some of the postmodernist notions influenced and inspired Holzer’s works during the second- and third-wave feminist movement.

To begin with, let’s take a quick look at the relationship between the postmodernism and feminism. Postmodernist art critic Craig Owens aptly noted in his work “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism” that postmodernism brought about “a crisis of cultural authority.” The idea of European cultural monopoly, during the postmodernist movement, had long been dissected and concluded as unsound. The plurality of cultures makes each culture an “other” to each other, a quality that resembles the conventional idea of women: in our patriarchal world, women are often considered an otherness to men when the reverse is not true.

Postmodernists’ calls for the signifier’s liberation from the “tyranny of the signified” revealing to the world what was hidden and invisible in representations. Historically, it was socially mandatory for females to reside in a masculine position—which is likely not a thing of the past but a thing still extant—so that they could represent themselves in the male-dominated culture. The idea that women can never fit into patriarchy as well as men do is apparently problematic, but none of us can deny certain practices of the women in the past, such as female writers like Charlotte Brontë, or more notably, George Eliot, who is lesser known as Mary Ann Evans, adopted male-sounding pseudonyms in order to gain a chance to publish their own literary works. Far away from the West, Hua Mulan from ancient China put on a similar representation by disguising herself as a man to join the army on behalf of her elderly father so as to spare him from the fate of being sent to the merciless battlefield. These are, of course, some of the more prominent example stories, with possibly many others remained undiscovered and unrepresented within hierarchies. One of the aims of the feminist movement was, therefore, to work against the invisible, the false representations of the female (in the sense that women needed to take up male positions in order to represent themselves within patriarchy), an idea that coincided with the postmodernist scheme of working against dominance. This aim found a common ground with the postmodernist movement, in which artists set out to destabilizes those who assumes central, dominant positions within any system, along with their unquestioned powers.

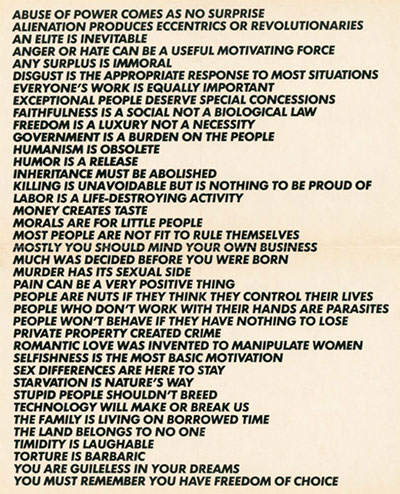

Jenny Holzer is one of the second/third-wave American feminist artists—a label that the artist herself happily accepted—whose works focused on dissecting and analyzing the power of language and violence through visual artworks. The Truisms series (1977-79), which was a series of posters printed with a list of oxymoronic slogans arranged alphabetically (Fig. 1), could be found everywhere on the streets of Manhattan in New York City. An example of the posters is shown here:

Living

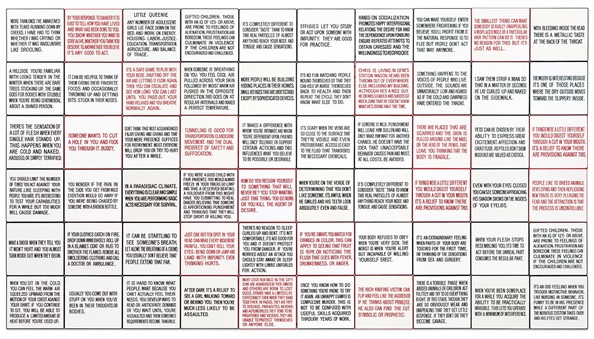

From that point on, Holzer switched her method of creation that started from Truisms to write with “a single voice in a more neutral or institutional format,” i.e.: neither female nor male, in the 1980-82 Living series. She used materials conventionally intended for memorials, office door signs, and plaques made for construction site names. Some of the finished products were camouflaged as typical office plaques and were put next to the real ones (fig. 2).

Holzer also exhibited her works in a different setting, e.g.: museum and gallery, where signs were grouped as a big collection and presented in one place (Fig. 3).

This series was a step-up from her earlier Truisms series. According to Holzer, she was able to “switched from being everybody to being [her]self” when she worked on her Living series. This time, Holzer inscribed longer passages and sentences that formed inconclusive stories in her works, then put them up in unexpected places of the walls in upper-class environments. She named the subject matter “everyday life with a twist”(1) due to the “unexpected” nature of the works, the way short sentences were engraved onto plaques instead of commonly seen names on signs that were part of an infrastructure. Her works also demonstrated the importance and prevalence of signages in the day-to-day American life. This series of installation artworks aimed at provoking emotions while leaving a sense of suspense in the readers’ minds: “to have the look of a voice of authority, of the establishment while remaining anonymous.” Judging from this description by Holzer, this “voice” from her creations signifies a form of surveillance: the work was there as reminders and warnings, but the audience would not know where this work come from, who produced it, or where would the sign lead them to. The colors of the signs, which were the same as other signages, allowed them to blend in perfectly with other signs. It is only upon careful examination would the viewer discover subtle and interesting difference between real signs and Holzer’s signs. Much like how women fit in patriarchy, signages signals authority, but in Holzer’s case, an uncanny kind of authority: they were to remind viewers of the reality and to make them question their perceptions of how they normally saw things. Holzer’s plaque series was a unique and crucial work for the feminist movement in the sense that, like graffiti, they “attacked” the walls without prior notice; but unlike graffiti, her works claimed the authorial, central position that viewers were unprepared for.

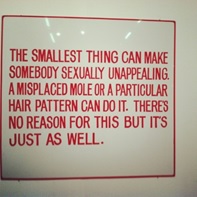

It is because in this series, Holzer attempted to undermine the difference between private and public spaces: anonymity means privacy whereas the publicly-known voice of establishments belongs to the realm of the public. This series adopted the idea of double-coding from architecture, which meant to train architects “to look two opposite ways at once,” thus providing a possible solution to both the concerns of architects and the ultimate users in a construction project. The majority of this series focuses on daily lives, illustrating the postmodern notion of merging arts with our culture. More specifically, Holzer confronted the issues of oppression women are still facing. Holzer, in fig. 4, addressed problems brought by sexuality and victimization in sexual crimes, and in fig. 5, sent a warning and empowerment to females at once, to raise their awareness of taking up the responsibility to stand up for themselves, to not to expect protection from men.

Lustmord

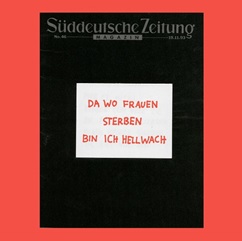

In 1993, Holzer’s 30-page writing Lustmord was published in a German newspaper weekly magazine, Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, in the form of photographs. It featured sentences written on human bodies, and the cards glued to the cover of the magazine were separately printed with a mixture of red ink and human blood, donated by German and Yugoslavian female volunteers. As the AIDS epidemic remained rampant in the early 90s, Holzer’s magazine artwork, which connoted impurity, expectedly sparked controversies. Human blood, however, is among the most common bodily fluids that we could chance upon in any occasion, not to mention scientifically, the small amount of dried blood Holzer used together with the red ink was unlikely to transmit any diseases to human beings. A question worthy of asking here is, why do we feel repulsive toward the blood when we see blood from another individual, but not so much when we touch our own blood? If the cards were in any way “sensational”—as criticized by some—the emotional effect that Holzer brought to her audiences can only imply she did something right.

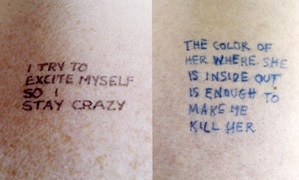

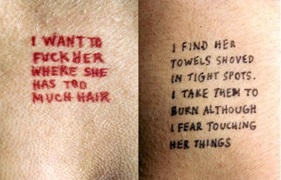

Lustmord was later presented along with Holzer’s other installation arts in exhibitions. Also included in this series were a group of human bones bearing silver bands etched with the word Lustmord. Lustmord is a German word which can be roughly translated into “rape-slaying,” “sex-murder,” or “lust-killing.” In an interview, Holzer commented that she “didn’t think the writing could be complete if it written solely from perspective of raped woman” and she “want[ed] to be able to explain the act to [her]self and then to other people.” Her writing on human bodies in this series differed from her Living series by the fact that Holzer created her works with high-end looking bronze plaques and installed them in formal environments, posing a stark contrast to her less sophisticated construction site plaques from her earlier Living series. Lustmord did not seem to be targeted at upper-class audiences like her Living series, but simply readers of a magazine supplemental to a newspaper regardless of social statuses. The photos were not just pictures of handwriting on human bodies, but more distressingly, pictures that showed her audience the magnified imperfections like hairs, pores and freckles on human skin, a reality that most of the fashion world does not want us to see. In addition, Holzer went back to her earlier practice of working with more than one voice/perspective of viewer in this series of work: using first-person point of view, each of the story was written from three perspectives, the perpetrator, the victim and the observer. The stories described by the short passages were, of course, far from pleasant, but the language of all three stories was surprisingly calm, or even slightly indifferent. This engendered a difference in audience’s emotional reactions, because the victim of a sexual crime is usually expected to be hysterical or furious, the perpetrator is usually cocky for the “victory”, and the perpetrator usually righteous or indignant—think of the recent hit TV series 13 Reasons Why. But Holzer deliberately wrote them in such an ambiguous way that when the writings were presented to the public for viewing, the audience, quite similar to her Living series, would not know the gender and opinions of Holzer—although the artwork itself made it clear that the artist herself was far from indifferent.

According to Holzer, Lustmord was initially prompted by the atrocities in the Bosnian War that took place between 1992 and 1995. To her, the series was “about what happens in other wars, and in peace time, in love and hate.” The violence from the Bosnian War was purposefully reduced to a rape, a matter on a personal level, and by doing so, it allowed the audiences to feel what happened in the seemingly faraway Bosnia and Herzegovina, in places such as Germany and the United States, where large-scale armed conflicts military were absent.

This particular project of Holzer, again, embodied both ideas from postmodernist and feminist movements. Most contemporary societies have a predetermined assumption on the gender of rape victims: whenever someone brings up such news, the listeners almost always assume the victim to be a female. As illustrated in fig. 7, the blue quote on the right reads, “the color of her where she is inside out is enough to make me kill her” (emphasis added). The perpetrator in fig. 8, who narrated the story, also indicated the victim was a female (see the red quote on the left above). Whether the perpetrator character and observer character in those stories were female or male remained unclear(2), but what is important is that, like how we learned about news from the media, the victims are female most of the times. Presenting from a clearly biased point of view, when visual arts are, again, expectedly subjected to scrutiny and criticism, even more so than news reports on such news, it is only natural to surmise that Holzer’s works were deliberately presented in such manner.

The emotional responses toward Lustmord, naturally, ranged from “tears to outrage,” with most outrage came from her male audiences. The reactions from male audiences are understandable because this series of artworks was intended to be an attack to the male when audiences tried to view the stories from a male perspective. The outraged responses from men indicated the works posed challenges to male-dominance effectively, from the compulsory male rapist implication. Her works, however, could not eschew from criticisms for why the victim had to be a female, because such crimes happened to men too. As a feminist artist who worked with words, a medium that is inevitably linked to male and words (i.e.: logocentrism), Holzer’s “bias” toward females is, however, more than justified. What is more, among the group of the most prominent conceptualist artists known for producing artworks with words, she is one of the rarity for being a female, with the other being Barbara Kruger. Sometimes, when an egg decides to bravely attack against a high wall—famously remarked by Japanese postmodernist writer Haruki Murakami—a more “radical” position is necessary and should be appreciated.

From the postmodernist’s point of view, Holzer’s writings from three perspectives and in three narratives – not just from the oppositional stances between the rapist and the victim, but also from the view of an ineffectual onlooker – was an attempt to relinquish the modernist, definitive meta-narrative. As explained by Holzer in her interview, Lustmord did not only happen in large-scale warfare (dead bodies in battlegrounds), but also in our quotidian life (bodies of the victims of a common crime). By incorporating and merging the supposed highbrow artworks with popular culture in her Lustmord series, Holzer made her stance clear by criticizing the world’s injustice fearlessly.

(1) Holzer later didn’t think the works were “twisted” enough, so she changed how she worked in her next series, Survival (1983-85), in which she used L.E.D. billboards instead of plaques.

(2) Some posited that the stories were made up of a male perpetrator, a female victim and a gender-neutral observer, but there was no male or gender-neutral pronoun (the singular they) involved, and secondly, Holzer never mentioned such setting except for the victim. Another point of criticism was that Holzer’s works were too sensational for her use of human blood. But artworks were supposed to be sensational, as they were produced to elicit responses and reflections. Holzer’s works were merely photographs, thus they are hardly sensational when compared those on our day-to-day newspapers.

Works Cited

The Art Story. Jenny Holzer Artworks & Famous Art | TheArtStory. www.theartstory.org/artist/holzer-jenny/artworks/.

Cohen, Alina. 13 Artists Who Highlight the Power of Words. 5 Jan. 2019, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-13-artists-highlight-power.

Holzer, Jenny. Jenny Holzer. Phaidon, 1998.

—. “Lustmord.” Jenny Holzer, Lustmord 1993, EXHIBITIONFEM, 24 Feb. 2015, exhibitionfem.wordpress.com/2015/02/24/lustmord/. Accessed 10 May 2017.

—, and Joan Simon. “Jenny Holzer, Joan Simon.” PressPLAY: Contemporary Artists in Conversation, Phaidon, 2005, pp. 316–335.

—. Jenny Holzer: Signs. Institute of Contemporary Arts, 1988.

—. Perspectives 102: Jenny Holzer: LUSTMORD. 1997, vdocuments.site/reader/full/perspectives-102-jenny-holzer-lustmord.

Jencks, Charles. “Post-Modernism as Double Coding.” What Is Post-Modernism?, 4th ed., Academy Press, London, 1996, pp. 29–40.

“Jenny Holzer Most Important Art.” The Art Story, The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist-holzer-jenny-artworks.htm. Accessed 10 May 2017.

Meskimmon, Marsha (2000): Jenny Holzer’s ‘Lustmord’ and the project of resonant criticism. Loughborough University. Journal contribution. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/8745

Owens, Craig. “The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism.” The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Hal Foster, Bay Press, Washington, 1983, pp. 57–82.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Jenny Holzer is one of my all time favourite artists.

I think she is focused too much on the message and not enough on the art. At the end of the day, it is the art that will make her message resonate. Art is the difference between the artist and the none artist, not insight or intellect.

I agree, there was an interesting idea trying to get out but she hasn’t succeeded.

I lecture to hundreds of students every year at university and Jenny’s work is often challenging and thought-provoking, teaching students to distrust appearances, advertising copy and easy conclusions and cliches, especially the way she display her works in specific sites and places. The way her works are displayed, according to many of my students, disorient them in interesting ways, making familiar and habitual places, opinions and expectations, unfamiliar.

Unfamiliar? Really? She has been doing the same shtick for over 25 years.

You are obviously very old. My students are 18-25 and find her work unfamiliar in the sense that it looks familiar but not quite.

No, not old, but wise enough to understand that the artist has been utilizing the same approach and style to her work for many years, and probably doesn’t warrant more than a few minutes of discussion in the grand scheme of art education.

She is great. Direct, acerbic, funny, direct, honest, and politically driven. Good art doesn’t have to be a skill with a brush or a pencil. I’ve got some recordings of her reading that work really well.

Thanks Ms Holzer for all your great work.

I love Holzer’s work, there is something about bold uncompromising statements that get the cogs whirring.

Sometimes, the problem with this sort of art is that it needs to be explained. Art that needs explanation has signally failed because you’d be better off with prose in the first place.

No it doesn’t. It’s poetic and visual, so what else do you need to know? She’s a great artist.

It’s difficult to think of any great art that doesn’t require some kind of explanation to the completely uninitiated. Michelangelo, Titian, Rembrandt, Turner etc. all require context whether it’s religious or classical symbolism, knowledge of the patrons or historical context of industrialisation.

I think the argument is whether you can enjoy the way the artist has painted a picture without needing to know the exact story it tells.

That’s a reasonable argument but it rests on the idea that there are strict divisions between the word and the image and that you should never try and bridge those divisions. Which in this day and age just seems daft.

You’ve helped me understand conceptualism better. Thank you.

Conceptual art seems to convey more feeling (for me) when I observe it.

I have seen Holzer’s work in many exhibits in New York and I do recognize that she is a serious artist and that her output is, in fact, art. I do however, have some problems with her obvious messages, didactic approach and political correctness. Robert Hughes once dismissed her work as “failed epigrams… unpublishable as poetry but survived in the new art context…etc.”

While this may seem harsh there is some truth to this. nk the problems set in when art gets too tangled up with mass media. The more the media aspect takes over, the less powerful the art. Art is stronger when it does what mass media cannot.

You may have a point, there. Phil Leider, former editor of Artforum, argued that Holzer’s work is merely a visual reincarnation of Andy Warhol’s bland generalizations. Could be… Or maybe it’s a little bit more than that.

Thank you for the splendid article on Jenny Holzer.

I had a white t-shirt of hers in the mid 80s that was covered in small black print in slogans, maybe 40 of them. People stopped me all the time to read them. There was always discussion about them. Many of them seemed contraditory, which made them even better. One definition of good art is something that makes people react, stop, think, stare, and get into their heads.

No question Ms. Holzer is just that.

Having made political art myself, I know how uncomfortable it can be. But I also know that at the same time one can almost become comfortable with this kind of onslaught.

Some of her texts really hit me and I’m glad that you covered her so now I know were to go for more great art to make me go into existential thinking mode!

I’ve seen at least one of her installations at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. It’s a little hypnotic and really awesome. My introduction to her was probably that Kurt Cobain/Nirvana photo in front of one of her marquees …

I have always enjoyed the use of letters combined with paintings. Her work is wonderful….interesting the geometric works seems almost more accessible than the works with words.

I just don’t see the point of Holzer, her comments are trite and there are poets that can say far far more then her with far far less words.

I briefly came across her work in an exhibit during Nuit Blanche in Toronto a couple years back. Her art really gets under your skin, in a good way

Jenny is very interesting. Thanks for sharing.

I do see quite a bit of this art in the modern sloganeering culture of today. Just an observation. Nice analysis!

Marvelous artist. Saw her “Truth before Power” in Austria a few years ago.

Big Jenny Holzer fan thank you for this in-depth look.

Thank you for this interesting article! I appreciated the links you created between postmodernism and second wave feminism as concepts and the analysis of Holzer’s works not only as individual pieces but through a perspective of an artist’s growth and her cultural impact.

Very interesting. I find the concept of postmodernism to be self-absorbed and lacking in social reality. Feminism (and Feminist art) is about gender equality, challenging the status quo of the heteronormative patriarchy and fighting against sexual discrimination. It has been about that for hundreds of years – there is nothing postmodernist about it. I am all for art that seeks to challenge everyone and makes us consider where the power lies but let’s not get distracted by unnecessary labels.

To define feminism as a quest for “gender equality, challenging the status quo of the heteronormative patriarchy and fighting against sexual discrimination” is an oversimplification. There are, in fact, different branches of feminism. And like I stated at the beginning of my article, not everyone agreed on the existence of postmodern feminism, but not for the reasons you cited here.

I agree that this complex issue can and has been over simplified, and I am aware of the various branches of feminism, but do you not think the straight forward call for gender equality can become lost amongst all the noise of figuring out what type of feminism it is?

Figuring out the type of feminism Jenny Holzer was advocating for was never the focus of my writing.

I love how she takes the traditional formats and spaces of advertising as a medium of political art.