Passion Pit: The Personal and the Political

The personal is political. That’s the type of mantra one becomes aware of when studying performance art. In it’s original context, it was used to describe performance that came from the second wave of feminism and used personal experiences to draw political parallels, normally based around issues of gender, something that can be seen in work by artists such as Bobby Baker, who’s performances Drawing on a Mother’s Experience and Pull Yourself Together! explore gender and mental illness respectively.

In more contemporary circles, the personal may not be quite as political as it was, but it seems to have a newfound importance on the way people approach art. The personal becomes integrable, because it’s through the personal that audiences relate, on various levels, to the work that they’re experiencing. For better or worse, audiences are now drawn to work that they can relate to, they like being able to see people like them on screen, on stage, on a page, or on a record. These issues were placed front and center when Michael Angelakos came out as gay on an episode of The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast. “I am saying something that I’ve never said publicly,” Angelakos told Ellis as he revealed his sexuality to not only the controversial author, but anyone that would ever listen to that episode of Ellis’ podcast. For all intents and purposes, Angelakos’ sexuality was now a matter of public record.

This isn’t the first time Angelakos has discussed his personal life in detail; his struggles with bipolar disorder were discussed with Rolling Stone three years ago. After an open letter revealing his condition, as well as a string of cancelled performances to help him through a recovery period, the public seemed to throw up their arms and say “we like listening to your music, but really don’t care what else you may be going through. Play our shows, damn it, or else.” This makes Angelakos’ decision to come out, especially in such a public manner, a strange one. There must have been fear of backlash, of hate, or even just of indifference, of people once again saying they don’t care what Angelakos is going through. But a lot has changed in the three years since his open letter and Rolling Stone interview, one where he described his mental illness as “all-encompasing,” as well as discussing the stigma that surrounds both bipolar disorder and mental illness more generally. In the years that have passed, the need to relate to both art and the artist has become paramount; now people might find a kindred spirit in Angelakos, and a certain, undefinable je nais sai quos in the music of Passion Pit.

The Cult of Relatability

Of course, things like this are never that simple. Relating to art may help, but in a way, it can close some doors in spite of opening others. Throughout the current run of episodes of The Bret Easton Ellis podcast, he’s been focused on what calls the “cult of relatability,” how people look at the art rather than the artist (citing a thirty-year-old Springsteen interview), saying that “the art should stand as the truth of the artist. And the artist themself? Eh, who cares? You’ll probably be disappointed.” Ellis argues that in some contemporary discourse, the narrative of an artist becomes more important than the aesthetic of the art itself; the former overrides the latter. This idea becomes particularly interesting when considering he discusses these issues in a monologue before the interview and, later, coming out, of Angelakos.

The irony of some of the response to Angelakos’ coming out, being called a “brave and talented man” by Salon, is the sort of thing Ellis would hate. In a piece from 2013, Ellis asked “Was I the only gay man of a certain demo who experienced a flicker of annoyance in the way the media treated Jason Collins as some kind of baby panda who needed to be honored and praised and consoled and—yes—infantilized by his coming out on the cover of Sports Illustrated?” It’s interesting looking at the way that Salon immediately refers to him as brave seems to almost hijack Angelakos’ personal narrative and makes it about other people, saying “we appreciate when someone expresses it more eloquently than maybe we ever felt it,” and while that might be true, it takes the personal out of the equation for Angelakos, and instead politicizes it, makes it about other people and their response and what they get from it, what Ellis would call “the sentimental narrative of a groupthink.”

In the aforementioned 2013 piece, Ellis says ” God help the gay man who comes out and doesn’t want to represent, who doesn’t want to teach, who doesn’t feel like part of the homogenized gay culture and rejects it,” and again, here we see the way in which media response, not just to Angelakos’ coming out, but the act of coming out more generally, becomes about other people rather than the person who comes out.

Life Among the Artists

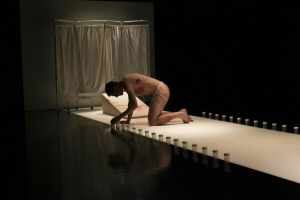

The personal and the political are no longer intertwined in the ways they used to be. Even in contemporary performance art – where the term first gained traction – work is more about the personal itself than how it reflects a macrocosmic idea; performances like Breathe For Me by Martin O’Brien deal explicitly and viscerally with the personal; in this case, with the reality of living with cystic fibrosis. One doesn’t need to have lived with the illness, or even known someone who has, in order to appreciate the power of O’Brien’s performances, or to feel, on a gut level, what it is that he’s feeling when he presents his almost naked body to those that watch him.

Would O’Brien’s work be more affecting on an individual who, like him, suffers from cystic fibrosis? Perhaps, but that seems like it would only make the already existing connection between art – or artist – and audience, stronger. Not having first hand experience with the issues O’Brien gives corporeal form in performance by no means excludes one from experiencing those feelings, or appreciating the brutal aesthetic of his work.

So, does Angelakos coming out alter the way audiences will relate to Passion Pit? Of course. There’s now, whether Angelakos wants it to be there or not, a new way of interpreting every word, note, and rhyme on every song Passion Pit ever have recorded, and each new song they release. But, to assume that by opening this personal door, by choosing to be vulnerable – not brave, but vulnerable – and reveal this deeply personal piece of information to the public, would close off anyone else who has never felt the same way, feels childish, narcissistic, and a disservice to art that everyone allowed to speak for itself. It’s only now that people may let the personal speak over it. The personal and the political are different now, it is more rare to see them joined together explicitly; instead, there is the possibility, or perhaps the fear, that the political will be forced upon the personal instead.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I have learned so much about him and Glenn Tyler coming out. I don’t want to be the gay who got married, or even worse had children. I want to be myself. There’s plenty of role models to look up to now, and gay people are no different than anyone else. Wishing the best to Mr. Angelakos!

Thanks so much for this post.

Great band and kinda had a crush on him… awkward.

Good job looking at the connection of the personal and public in art. It can be hard to navigate because there is the aspect of audience relatability where the audience can feel less alone, but there is the potential of infantilizing the artist involved. And you’re right that while sharing the artist’s struggle can provoke empathy, one can still appreciate the talent and emotional power of a performance piece without enduring the same issue.

Being personal and political does make one vulnerable because no one knows how the audience will respond. Sometimes people question the authenticity of a personally motivated political artistic expression but in my view as long as the artist owns it, then he/she should be allowed to creatively let loose. The more freedom of creative expression, the better.

People love Passion Pit. Don’t hate on the band.

Never heard of passion pit.

Same.

I cannot help but wonder if some of Michael’s depression issues stemmed from his not being able to be his one true self? I hope he finds ever lasting happiness. He really is a talented person.

There is always a bond between the artist and the man… In your performances you’ll ever find something about your essence, about your personal dramas… What you feel will always have an impact in what you do, and this makes us humans, we can’t completely be another person on the stage or in what we do, our emotions shine through our eyes and acts … And people judge artists for their private life, achieving the right to make them suffer or to elevate them

This article gave me insight and useful ideas.

Not familiar with their music. Googling now.

He is 28 now so hopefully he found himself. It takes longer for some people.

Passion Pit’s music has always spoken to me. I love how personal the writing is and how it touches on relevant topics. This article is great in depicting the details how the artists must weave their personal lives with the political in order to be truly effective.

Really neat post

Very intriguing article. The performing arts in regards to the personal is political can almost always guarantee backlash. Martha Graham for instance was firm in a political approach to her choreography even after a Russian artist depicted her in a comic as a ‘weak’ representation for the United States. This resulted in the US trying to stifle her work and regain a ‘masculine’ appearance to the world.

It is important to note that the context analyzed in this article is North American and not universal. The patterns of interaction among the artist and the audience vary widely outside of the Western world. In Latin America for instance, the artist and the intellectuals have always had strong roots in the popular audiences that do not rely on familiarity, but instead in political identification. Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci theorized the role of the artist/intellectual in these sort of scenarios as “organic intellectuals.” His analysis might be of use to deepen on the topic. Overall, while I do not disagree with the author when referring to the relationship between artists and audiences in North America, the dictum that the personal is not political should not be universalized through discourse, since it ignores the reality of other cultures.

The phrase, “ the personal is political” has a truth to it but the words need to be tightly defined, because it can lead to errors in reasoning otherwise.