Analyzing Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Female Leads

Composer Richard Rodgers and lyricist Oscar Hammerstein are synonymous with some of America’s oldest and best known musicals. The moment one brings up The Sound of Music, Oklahoma, Carousel, or any number of other theater productions or films, their names are bound to follow. These two are so ubiquitous, they’re often connected to musicals in whose productions they never participated. Their first six and most famous musicals have been sold in VHS collectors’ sets for decades, and when VHS gave way to DVD and BluRay, Rodgers and Hammerstein kept up with the times. Their musicals can now be streamed for free, purchased, or rented across services, including Amazon Prime, Google Play, Apple TV, and even Disney Plus.

Rodgers and Hammerstein have legions of fans across generations. Grandparents have introduced their grandchildren to the paragons of musical theater, and the grandchildren have grown up to perform stage versions of their musicals in high school or college productions. Today’s grown grandchildren and great-grandchildren may not know Oklahoma or Carousel as well as they do Wicked or Dear Evan Hansen. Yet they probably recognize roots of “old school” musicals in their favorite new productions. The most ardent “theater kids” of the past generation or two might own merchandise that says, “I liked musical theater before it was cool”–because it’s true. They were more than ready by the time musicals became trendy, and now they are the experts to whom peers turn when audition time arrives or authentic cosplay gear is needed.

Like most “old school” paragons though, Rodgers and Hammerstein (R&H) have endured the “problematic” label since their most famous sextet of musicals were trendy in the 1950s and ’60s. Traditional gender roles look sexist to the 21st century eye. Historical truths of colonialism or oppression read sanitized, often romanticized. Since the musicals are marketed as “family” films–read: for adults as well as children–this sets up R&H to be “cancelled” for offending adults and sending kids misguided messages.

Yet, R&H plays and films are not as sanitized and sugary as they might first appear. Nor do they ignore the difficult parts of life, no matter the era, setting, or plot. These musicals often strike an interesting balance between surface-level enchanting idealism, and an underlying layer of grit. Granted, some productions do a better job of conveying this balance than others. Some issues aren’t covered well or at all in the original musicals because of their original production eras. This has led many directors and producers to update some of the original material, leading to everything from critical praise to accusations of letting Rodgers and Hammerstein “go woke.”

Our discussion will examine one facet of this team’s work: the roles and treatment of their female leads. We will examine four musicals, not six, because of how well the four musicals featured contrast as pairs. That is, one pair will be discussed as the “classic ingénue” pair, while the other will be the “dramatic ingénue” pair.

We will examine these heroines for the historical, yet relevant characters they were and are. That examination will let us determine how Rodgers and Hammerstein developed their female leads over time, what they might have intended to say with their original material, and what the female leads have to tell us today.

The Classic Ingénues: Laurey Williams McClain and Julie Jordan Bigelow

Our discussion begins with our “classic ingénue set,” or a pair of leading ladies who embody the accepted meaning of the theater term “ingénue.” Laurey Williams McClain and Julie Jordan Bigelow, both played by Shirley Jones in 1955 and 1956, appear in Oklahoma! and Carousel, respectively. They were R&H’s first ingénues and perhaps the most famous.

A classic ingénue is “an innocent or unsophisticated young woman, especially in a play or film.” The ingénue is usually characterized as “gentle, sweet, kind,” and naive. She has little to no experience with men and is “often the target of the cad, who she may have mistaken for the hero.” Even if not a target, the classic ingénue is more prone to idealistic romantic fantasies than her foils, the dramatic ingénue or more commonly, the vamp.

In theater, she is nearly always a first soprano. Barring youth productions, she’s usually in her late teens and often no older than 25. Arguably, Shirley Jones’ back-to-back portrayal of the classic ingénue gave musical viewers and perhaps directors and producers an idealized picture of this type as a wide-eyed blonde with a vibrato-heavy singing voice.

Any modern versions of Laurey or Julie need not be blondes. Nor do they need the operatic voice Shirley Jones possessed. But any woman playing either of these two will quickly notice plenty of subtext in how she’s portrayed and how her character grows in the production. Said subtext, and the way a modern actress handles it, can leave audiences with new thoughts regarding what R&H might have meant to say about the classic ingénue.

Oklahoma!: Western Fairy Tale or Scary Tale?

Oklahoma! began as a 1943 production based on Lynn Riggs’ play Green Grow the Lilacs. It became a film in 1955, with Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in the lead roles of Curly McClain and Laurey Williams, and Rod Steiger in the role of Jud Fry, a bitter, villainous farmhand. The story is set in Oklahoma Territory, 1906, one year before said territory’s official statehood. It has many detractors, ironically and especially in Oklahoma itself.

Those detractors have more than one good point, as the original musical is full of problems. It makes no mention of real Oklahoman history, including the Trail of Tears. Many detractors grouse, either lightheartedly or seriously, about how the story stops cold so the actors can rhapsodize about how great Oklahoma is (while leaving out realities like tornadoes, economic hardship, lawlessness, and even the inevitably of the Dust Bowl in 20-odd years). The 1955 film highlights the actors’ abysmal attempts at authentic Oklahoman accents.

Just as the state has its devoted fans and citizens though, Oklahoma! had plenty of supporters in 1943, 1955, and today. The Oklahoma Historical Society calls it a popular musical all over the world, and many amateur productions have taken place in the last 30 years. A “stripped down” West End cast and a 2019 film remake have brought in new fans. Thus, it’s worth examining what keeps nostalgic fans coming back, and what brings new ones in. The answer is likely the simple, but layered love triangle at the story’s center. More to the point, the answer is the person at the triangle’s center: ingénue Laurey Williams.

Laurey Williams: Tangled in a Love Triangle

Laurey, about 17 when Oklahoma begins, checks all the boxes for a classic ingénue. She’s under the protection of her maiden Aunt Eller, who runs the family ranch with a combination of warm Western hospitality and the threat of her shotgun. In contrast, Laurey is schooled in “feminine arts” like cooking and sewing, but doesn’t take on ranch business herself. She spends the day embroidering, daydreaming, and bantering with Curly McClain, head of a neighboring ranch, owner of a prize horse, and very single.

Laurey indulges in sass and half-serious vitriol around Curly. When he enchants her with a song about the fancy “surrey with the fringe on top” in which he plans to drive her to an upcoming box social, Laurey is almost taken in–until Curly tells her he made the whole thing up. There “ain’t no sich a rig,” as Laurey puts it, and she shoves him away, chasing him off with a flyswatter. Still, Laurey is a sweet, naive girl at heart. At heart, she also has a major crush on Curly. Both have been “sweet on” each other since childhood, given how familiar Aunt Eller is with Curly and how eagerly she pushes him to romance her niece.

Curly has competition in the form of the Williams’ farmhand, Jud Fry. Jud first appears after Laurey has stormed off in an indignant rage, having fallen for more of Curly’s teasing–he did in fact hire a special “rig” from nearby Claremore to drive her to the box social, but since he “made up pretties” and was “tellin’ [her] lies,” Laurey won’t have him. Whether Jud just happened along or was waiting to make a move, viewers don’t know. But it is convenient that he shows up long enough to announce he needs to quit work early so he can drive Laurey to the party. Laurey neither confirms nor denies Jud asked her first, but doesn’t refuse when he clarifies he’ll pick her up later.

Curly is aghast at this idea. It’s not just that Jud is a man of few words, though he tends to grunt and phrase those words like demands. It’s not that he’s dirty; both men work the land, after all. Curly though, shows up at Laurey’s place clean, and he maintains a much neater appearance than Jud throughout the show. Curly seems more offended at Jud’s overall manner toward the Williams women. He seems too eager to finish work early and otherwise slouch around, and he looks at and speaks to Laurey like an object. Aunt Eller warns Curly, “Don’t you go sayin’ nothin’ agin’ Jud. Best hired hand I ever had.” But it’s inferred she, too, thinks Jud is trouble. With this in mind, she encourages Laurey to make her own choice. Unfortunately, Laurey can’t extricate herself from Jud.

Brave Words, Frightened Heart

Despite her rejection of Curly and her almost fearful attitude toward Jud, Laurey stays entrenched in romantic idealism. Some of this is sensible, as seen when she advises her friend Ado Annie Carnes to make up her mind between longtime suitor Will Parker and new beau Ali Hackim (pronounced in Oklahoma fashion, short “a” and short “u”). When Annie laments she “can’t say no” to any fellow who wants to kiss her–and it’s implied, go further–Laurey advises, “You can’t just go around kissin’ every man that asks ya!”

The sad irony is, Laurey can’t or won’t listen to her own practical voice. Viewers can infer she would tell either Curly or Jud “no” if they got physical. She can’t make up her mind between the two as she urges Annie to do, however. More to the point, she won’t admit her feelings or the implications of either choice. If pressed, she repeatedly says she can’t accept Curly’s invitation because she “promised Jud.” Yet Laurey never says or does anything indicating affection or even friendship for the farmhand. Viewers get the sense Laurey’s promise was forced, if it’s real at all. She’s scared to turn Jud down, but admitting that would mean admitting she made a mistake and is less mature than she wants to appear. Worse, it might cost her Curly’s respect.

Laurey buries her emotions rather than deal with them. As with Curly, she falls back on sass and an independent facade. The song and ballet “Many a New Day” focuses on Laurey’s claim that she does not now and has never needed a man to fulfill her. She makes this stand in front of every girl in the neighborhood as they all “freshen up” for the box social at the Williams house. Inspired and presumably remembering their own “guy trouble,” the other girls agree with Laurey, singing “many a new day will dawn” before they’ll cry over men again. But the minute Laurey overhears Gertie Cummings’ obnoxious giggle and remembers Curly brought her to the social, she’s the one who breaks down. She recovers, but viewers know she’s fooling herself.

Romantic Dreams, Real Threats

Laurey’s naivete, and the emotional danger she’s in, reaches its peak after the “Many a New Day” number. She’s purchased some Elixir of Egypt perfume from Ali Hackim, after he promised her taking a deep sniff would give her clarity about any decision. Laurey inhales, whispering, “Make up my mind for me. I’m waitin’ for the answer,” and falls asleep on the porch. So begins Oklahoma’s longest and most famous dance number, a “Dream Ballet” wherein dream versions of Curly and Jud press their suit with a dream Laurey (all portrayed by different actors than the actual leads).

The Dream Ballet shows Laurey vacillating between Jud and Curly through dance the way she’s doing mentally while awake. Fairly quickly though, the dream Laurey chooses Curly, and her friends dress her as his bride with an orchestration of “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin”‘ playing in the background. Before the dream couple can be swept into their happily ever after though, the dream Jud pulls Laurey away. It’s implied she’s not officially married, so Jud still has a chance. The scenery and music darkens; many productions use eerie red lighting, and an orchestration of “Pore Jud is Daid” [sic] takes over. A gallows, minus the rope, takes center stage. Burlesque girls in heavy makeup and revealing-for-the-era clothing try to force Laurey to join their provocative dance.

A confused and devastated dream Laurey crumples and cries as her dream suitors fight in the gallows’ shadow, presumably to the death. Jud kills Curly, and Laurey is left to mourn. The real Laurey wakes to find the real Jud looming over the chair where she fell asleep, and cries out just as she screamed in her dream. “Laurey, it’s time for the party,” Jud reminds her. Divorced from context, this is just a statement. Given Laurey’s indecision and mental torture though, it reads like a threat. This is compounded with information Laurey doesn’t have. Namely, Jud enjoys looking at pornographic pictures, and the conversation he had with Curly before “Pore Jud is Daid” implies he’s killed before over a farmer’s daughter who rejected his advances.

An Almost-Grown Girl Playing Grown-Up Games

Even though Laurey doesn’t have this information, she’s been uncertain around Jud throughout the production. After the dream, her terror of him is more obvious to the viewer if not the surrounding cast. Still, Laurey uses Jud to make Curly jealous, assuming it’s an innocent ploy. But her naivete and romantic idealism mean she has no clue how ugly that could become.

Laurey wants to control her situation because she thinks that’s what a strong, experienced woman does. She sees Aunt Eller in control of the ranch, and running it well as a single, elderly woman. And while Ado Annie is conflicted, she has the romantic experience Laurey desires. Laurey’s desire to imitate these women is natural, and at least in Aunt Eller’s case, positive. The problem is Laurey’s complete lack of discernment. So although she wants to be with Curly, and viewers know Curly is the better choice, Laurey wrestles with cognitive dissonance.

On some level, Laurey knows Jud is a dangerous man, though just how dangerous, she’s unaware. On some level, she knows Curly can offer much more than fancy “rigs” and pretty talk. He truly cares about her. As seen in the song “People Will Say We’re in Love,” both parties are still in denial, yet admit real love is developing from their impetuous, vitriolic crush. Yet Laurey keeps pushing Curly away physically and emotionally, perhaps because she fears choosing him is too easy, not a reflection of her maturity.

In response, Curly walks away. This is probably because he understands Laurey is still “growing into” the idea of loving him, and growing up in general. Yet Curly may also walk away because he fears Laurey wants him to, or because a wounded ego won’t let him keep pursuing her. Unfortunately, this puts Laurey square in Jud’s sights, and may irreparably harm others, too.

A Damsel Rescued…But is it “Happily Ever After?”

Oklahoma’s climactic action centers on the box social, a party and fundraiser for the new schoolhouse hosted by Ike Skidmore, the town’s richest man and the one with the most kids. It’s here that the local young men will “claim” young ladies they want to court through two rituals. One is, of course, who drives whom to the party. The other revolves around the “box” part of the social, wherein men bid on picnic baskets filled with foods and sweets the young women have made. The highest bidder on a basket gets a “date” for the rest of the evening with the female chef, and all proceeds go to the schoolhouse.

No one is supposed to know which girl made which basket, but Ado Annie breaks that rule. She and Laurey were both late; Annie’s father had nearly pulled Ali Hackim into a “shotgun wedding” before realizing the peddler had not defiled his daughter, and that Will Parker had kept his promise to be “worth $50” and therefore worthy of Annie. Meanwhile, Jud drove so slowly Laurey feared they wouldn’t make it to the Skidmores at all. He then propositioned Laurey, accused her of thinking she was better than him when told “no,” and nearly wrecked their wagon.

By the time both couples finally arrive, only Annie and Laurey’s hampers are up for bid, which Annie announces to the crowd. Will wins Annie’s hamper with no trouble, but when Curly bids on Laurey’s, Jud keeps driving up the price by “two bits” no matter what he says (e.g., Curly’s grand total is around $30, which Jud drives up by what is today 25 cents).

Curly is so determined to keep Laurey away from Jud, he bids his saddle and horse, although rules state only cash counts. For his part, Jud keeps up the “two bits” routine, although he doesn’t have near the money he’s bidding. When Skidmore points this out–and adds everybody knows it–Jud storms off. He tries to kill Curly using the “Little Wonder,” a kaleidoscope with a concealed knife he bought from Ali Hackim–but Aunt Eller catches on and distracts both men. Undeterred, Jud finds Laurey alone and propositions her again, threatening and grabbing her. A shaken Laurey fires him and orders him off the property. She then runs off crying and, upon encountering Will and Annie, begs Will to find Curly for her. Curly consoles Laurey, teasing her to stop crying on pain of a “spanking,” and proposes to her.

Laurey accepts, but just after the wedding, Jud corners the couple and tries to burn them to death in a haystack. Curly jumps to Laurey’s defense, killing Jud and claiming the farmhand fell on his own knife. But this makes Curly guilty of manslaughter, so a trial must take place. While Laurey weeps and frets to Aunt Eller, Ike Skidmore acts as judge, feeding Curly an alibi about killing in self-defense. Since the entire town agrees with this, and knows Curly always meant to protect Laurey from Jud, Curly is declared innocent. The show ends with a proper wedding celebration, a celebration of statehood, and the showstopping “Oklahoma.” Still, discerning viewers might well wonder what Laurey Williams McClain has gotten herself into and actually learned from her “love story.” Moreover, they might wonder if they should take anything positive from this “Western fairy tale,” or if said tale is more “fractured” than it looks.

A Mix of Glitter and Grit

On close analysis, viewers may find Rodgers and Hammerstein’s overall story, and path for Laurey, is less tarnished than it looks. Yes, Laurey spends much of Oklahoma! as a weepy, foolish ingénue, so true to her type that in the 21st century, she is painfully stereotypical. But taken as a whole, her story is one that pushes her down a complicated path and challenges her to grow up before she can experience lasting happiness. Furthermore, Laurey’s journey leaves some questions unanswered, but not unsatisfactorily so.

In Oklahoma‘s first act, Laurey’s arc is a sweet, somewhat complicated one, but still simplistic. She’s torn between two suitors, but viewers know which she should choose. They root for Curly and against Jud, not because either is a particularly well-developed character, but because Laurey is a Western “princess classic,” a “damsel in distress” in grave danger if she makes the wrong choice. Viewers want to see Curly sweep Laurey off her feet and carry her into a perfect sunset, and they want the almost melodramatic plot that will precede such an ending.

Thus, Laurey’s vacillations might be frustrating, but they are a pleasant twist on a familiar story. They challenge viewers, and they challenge Laurey. The central question for this ingénue starts out as, “Am I mature enough to act like a grown woman,” because for Laurey, an act is much of what she has understood adulthood to be. As Oklahoma enters its second act, Laurey faces issues more complex than box social dates and dances. She confronts issues like attempted assault, manslaughter, and what she wants, expects, and will accept from a real relationship.

Laurey’s central question becomes, “Am I brave enough to be my true self?” That true self, she learns, is the person viewers saw earlier–the sassy, bantering girl, yes, but also the slightly older one who wants to be wise like Aunt Eller. It’s the girl who told her best friend to make up her mind, not to accept kisses from every interested man, and who stood up to Jud.

Much like the new state of Oklahoma, Laurey Williams McClain ends the musical, and her story, still new to a stage of life she isn’t quite prepared for yet. She is now tied to a man who yes, has committed manslaughter–much like Oklahoma Territory tied itself to a nation with a rough, bloody history. R&H don’t make any definitive statements about Oklahoma’s future statehood or Curly and Laurey’s marriage. However, viewers are meant to trust the state will be “okay,” because it’s good-hearted and tough. Similarly, Laurey will be okay, because she will develop the maturity and toughness she’s growing into, and because both she and Curly have solid hearts. In no way are they done with the grit of real life, but there will be plenty of glitter, like fringe-topped carriages and beautiful mornings, to sustain them.

Carousel: Hard Story, Hopeful Heart

Rodgers and Hammerstein’s second musical, Carousel, is based on Liliom by Hungarian playwright Fenrec Molnar. Originally written in 1909, it was first adapted in 1945 and its location transferred from Budapest to Maine. The exact locale is not named, but is based on Boothbay Harbor, ME. The film version came out in 1956, one year after Oklahoma!, and reunited Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in the two lead roles, Billy Bigelow and Julie Jordan Bigelow. The actual story is set in 1873, with a fifteen-year time skip to 1888 between acts.

Richard Rodgers named Carousel as his favorite of all the musicals he worked on. The production also garnered serious praise from other greats like Stephen Sondheim, who once said, “Oklahoma was about a picnic. Carousel was about life and death.” Like Oklahoma, too, Carousel is no stranger to controversy. Particularly today, fans and critics alike argue over the musical’s heavy themes and the implications of its messages. Namely, viewers question whether Carousel has a place in theater after the #MeToo movement, and what theater, and theater-lovers, should do with Billy Bigelow as one of theater’s “greatest anti-heroes.”

Much debate also surrounds Carousel‘s standing as a “love story.” As with Oklahoma!, that debate stems from Julie Jordan Bigelow, the female lead and ingénue. As with Laurey, the quickest and easiest answer to any debate about Julie is to “cancel” her and her story, because she apparently tolerates ongoing domestic abuse. But as with Laurey, there’s a deeper story behind Julie, one that keeps viewers coming back and finding something hopeful in her story.

Julie Jordan: Good Girl Headed for Trouble

Julie Jordan’s exact age isn’t given in either the original script or film version of Carousel, but unlike Laurey, she’s described as a “young adult.” She’s said to work at Bascombe’s Mill. These two clues could place her anywhere between 18 and 22, making her older and more worldly than Laurey, if not by much. Otherwise, Julie is another classic ingénue. She’s independent enough to manage her own money and travel alone. Yet she is under the protection of a boarding house matron and indirectly, her male employer.

She is held to strict rules like curfews on pain of losing her job, and presumed to be in danger if she’s found alone or with men in public. Her introductory song “You’re a Queer One, Julie Jordan” (“queer” meaning “odd” here), highlights Julie is an idealistic, introverted daydreamer. Best friend Carrie Pipperidge notes Julie is restless and absentminded, singing “Half the time your shuttle gets twisted…’til you can’t tell the warp from the woof.”

Julie’s dreamy nature attracts her to the carousel, the main attraction at the pier near where she and Carrie live and work. One May evening in 1873, Julie pays for a carousel ticket and catches the attention of barker Billy Bigelow, who claims he owns the carousel, using his supposed riches as an “in” to flirt with and seduce her. The two share a physical but innocent ride, and the actual carousel owner, Mrs. Mullins, becomes indignant, claiming Julie is a “hussy” who let Billy come onto her. She throws Julie out, and Billy comes to her defense, getting fired in the process. From there, the new couple’s flirtations continue. When Julie learns Carrie has a “fella” of her own, fisherman Enoch Snow, and plans to marry him, she becomes increasingly infatuated with Billy, perhaps because she wants to “keep up” with her friend.

Julie’s relationship with Billy starts getting her into trouble, such as when she’s caught out after curfew. She never would’ve done something like this before, and again, Billy defends her. Julie either doesn’t notice or doesn’t care that Billy’s anger is disproportionate to the situation. Nor does she catch on that Billy blames Mr. Bascombe for Julie’s transgression and Billy’s encouragement of it.

It’s unclear why Julie doesn’t make this connection. Perhaps she finds Bascombe, Billy, or both intimidating. Perhaps like Laurey before her, she falls into the trope “All Girls Like Bad Boys.” Perhaps she fears appearing to “side” with Bascombe and the rules of the boarding house will displease Billy and wreck her chances of having a “fella” like Carrie. Whatever the reason, Julie accepts Mr. Bascombe’s offer to walk her home and give her another chance, rather than fire her as the rules say he should. But she doesn’t consider whether pursuing Billy will cost her a job, a place to stay, or intangibles like reputation or self-respect.

Marry in Haste, Repent…Ever?

Like many musicals, Carousel doesn’t spend much time on courtship. What began as flirtation in May blossoms into marriage in June. “June is Bustin’ Out All Over” is the first act’s biggest number, a celebration of love packed with metaphors and innocent but pointed innuendos. In its course, viewers learn Julie has married Billy, and the couple has moved in with her Cousin Nettie. They’re living off her income since Julie either can’t work or isn’t allowed to, and Billy has never had a trade other than carnival barking. Julie does mention Billy could get work otherwise, but he shuts her down. Julie never mentions the possibility again. This might be because, as both Nettie and Mrs. Mullins point out, Billy has already hit her before. In fact, town gossip is, he “beats” her.

Billy hotly and repeatedly denies beating Julie. He clarifies he hit her once and deeply regrets it. Julie never clarifies one way or the other. She simply goes along to get along, serving Billy his dinner, making sure he’s feeling all right, and reassuring others–thus herself–he will start work when the right job comes along. Julie even keeps the news of her pregnancy a secret. She plays it like she’s waiting for the perfect time to tell her husband, as if it’s a joyous occasion for the two to share. But while Julie is legitimately happy, viewers know the truth.

Julie carries anxiety and fear along with her baby. Given how Billy has lashed out at her over much more trivial matters, she has every reason to believe news of a baby would incense him. Like many abusive husbands, he might blame her for the pregnancy. Never mind the fact that such a quick pregnancy would actually mean the couple got pregnant outside wedlock. In the time period, this would’ve put Julie in a terrible social position, while absolving Billy of responsibility.

Fortunately for Julie, Billy’s huge personality and almost uncontrollable emotions land on “joy” when he hears about the baby. He immediately becomes attentive, asking if there’s anything he can do and if Julie should be climbing stairs or carrying objects. Julie reassures him she’s okay, but Billy continues hovering. Viewers are then treated to the amusing yet touching “Soliloquy,” wherein Billy imagines what it might be like to have a son called Bill, whom he’d raise to be a junior version of himself. Halfway through, Billy does realize he could have a girl instead, and wakes up to the reality that, “You can have fun with a son, but you gotta be a father to a girl.” He reflects on some deep insecurities, letting viewers nurse some hope that his and Julie’s marriage will strengthen and become more stable. Hasty though it was, the couple may not need to “repent at leisure.”

Julie though, hasn’t done any reflecting or repenting that viewers can see. Granted, this may be because Carousel is written more as Billy’s story than hers. He is the “anti-hero.” He is the one with a past and an arguably bigger character arc. Additionally, Julie’s self-reflection may have been natural, since she’s been the one at home cultivating a pregnancy and working through the implications of a rushed marriage. However, neither she nor viewers can ignore, Julie is still the sweet but naive ingénue in this story. She has gone a step further than Laurey Williams, in that she is not simply in danger from Billy Bigelow. She has fully embraced the danger and due to her era, she has no easy way out. She has no “rescuer” as Laurey did with Curly. Redemption may be too much to ask, if she even wants it.

Julie’s Quiet Will of Iron

As Carousel moves toward its second act though, it becomes clear Julie may not need or want rescuing in the traditional sense. More importantly, redemption may be closer for her than viewers think, and again, it’s not traditional redemption.

In other words yes, Julie tolerates the common cycle of domestic abuse, wherein the abuser hurts his victim, apologizes, is on his “best behavior” for awhile, and abuses again. She continues tolerating Billy’s shiftless attitude, as seen before the number “This Was a Real Nice Clambake,” when she goes looking for him aboard the Nancy B, where he claims to have procured work as a deckhand, but cannot find him. Rather than press, Julie gives up. She gives up again later when Billy refuses to go to the clambake with her. When he “changes his mind” after a lucrative bribe from Jigger Craigin and bullies Julie into accompanying him, Julie gets pulled along. But underneath all this tolerance lurks a quiet will of iron that’s grown since her first carousel ride.

Julie embraces that will of iron on the ride to the island, right around “When the Children Are Asleep.” Most of that number takes place between Carrie and her new husband Enoch Snow, who fantasize about sharing sweet physical and emotional intimacy when their not-yet-born children are tucked into bed. In the film, the camera cuts away to Julie, sitting in the bow of Billy’s boat while he steers, back to her, in contrast with the giggly, cuddling Enoch and Carrie.

Here, Julie realizes she’s made a choice, and however hard it is, she’s going to stick with it. She has a child of her own on the way, and he or she will need a mother’s love. As for Billy, he may, probably will, not be the dad Enoch Snow will be. Whatever else he is though, he is Julie’s, and that’s reality, so she will make the best of that she can. If she can improve that, fine, but if not, she can be as strong as possible.

Julie’s determination pops up again during the clambake. Carrie vents to her about a quarrel she and Enoch had recently, leading to the song “What’s the Use of Wond’rin.” Many modern viewers read this number as Julie defending Billy’s abuse. In response, some production directors have changed the lyrics or tone so that it reads more like Julie singing as a battered woman. Failing that, they may change the singer; for example, a naive Carrie may sing it in contrast to Julie, showing how different and privileged her marriage is.

In reality though, as one theater blogger puts it, “What’s the Use of Wond’rin” is really Julie saying, “It’s nice that Carrie can [gripe] about the way he wears his hat…this is my reality.” Such an interpretation not only gives the song a darker tone, but underscores how quickly Julie is losing her “classic ingénue” status. It also underscores how that loss may cost her, but ultimately serve her well in the end.

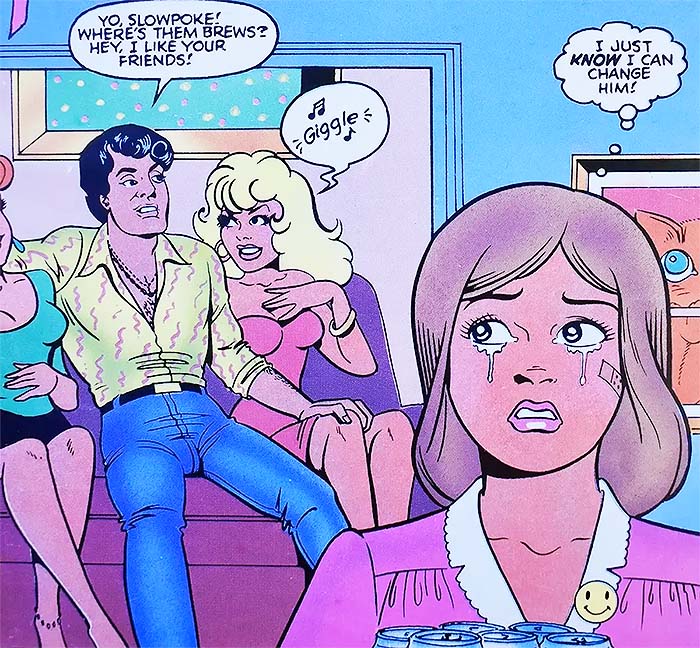

Some, perhaps most, modern viewers might see Julie’s trajectory as the “I Can Change My Beloved” trope. Others might argue whatever will of iron she has crumples right away, after she finds Billy dead following his failed attempt to rob Bascombe of the cash prize from the annual clambake treasure hunt. But while Julie does sob, “What am I going to do,” in Nettie’s arms, her will of iron does not crumple. Nor does she mourn a chance at “changing” Billy. Recall, she already had multiple chances to do so, and any efforts she made were few, far between, and not at all wholehearted.

Rather, Julie’s reaction to Billy’s death is an outpouring of grief she’s carried since her marriage began. It’s likely a manifestation of grief less for Billy himself than for the woman she could and should have been, both before and with Billy. As Nettie says, now, what Julie will do is go on living. Even before Billy’s death, she has taken a big enough step out of the classic ingénue role, to begin to learn how to do that. Julie cannot redeem Billy or his life; as viewers have seen and will see in the conversations between Billy and his Heavenly Friend, only Billy can do that. Nor can she redeem any love they had for each other. What Julie can and will do is something Laurey Williams was unable to do. She will find rescue and redemption for and through herself.

Learning to Sail Her Ship

After Billy’s death, Carousel skips fifteen years, to 1888. The story’s focus switches back to Billy, who has been in a friendly form of purgatory with a Heavenly Friend all this time, telling said Friend the story of how he lived the last few months of his life and how he got to the afterlife. God, or the Starkeeper in Carousel, has called for Billy because although he waived this right at first, Billy has the opportunity to go back to earth for one day to complete any “unfinished business” he might have. In light of the story he’s been telling, Billy now considers using his one day. He confirms the decision when his Friend tells him he has a fifteen-year-old daughter, Louise, and that she is unhappy.

Heavenly Friend explains that while Billy can see Louise, Julie, and anyone else he likes, they won’t see him unless he wants them to. Billy checks on Julie and sees she’s remained single, giving music lessons to the town’s children in a house of her own. She’s now the respected “Mrs. Bigelow.” Louise, though, is having a much harder time. She’s growing up a lot like Billy–free-spirited, spending much of her time alone on the beach. Viewers know nothing about her hobbies or talents, though the film devotes over ten minutes to a music and dance number wherein she turns cartwheels on said beach and dances with a performer from a visiting carnival.

At the end, several schoolmates, including one of the Snow daughters, mock her, “Shame on you, shame on you, shame on you!” This represents Louise’s reputation and place in town. Her mother may be pitied and respected, but Louise is not. Instead, she’s seen as a female copy of her suspicious, shiftless, dead father, who may also have her mother’s less respectable traits. This is underscored when the Snow daughter brags that her father, who is alive, bought her a pretty dress for the upcoming graduation. The implication is that Louise, whose father is dead and who has less money, is a lesser person.

Louise is devastated, so Billy chooses to see her without telling her who he is. He then tries to encourage her, calling her “darlin'” and offering her a gift. Louise, understandably wary of a strange man on her property, puts him off, and Billy ends up slapping her. He goes invisible again, and Heavenly Friend warns him he “struck out,” chastising him for the behavior pattern of slapping and pushing away people who don’t do whatever he wants. Friend is fairly subtle, but goes on to warn Billy this kind of action may get him sent to hell if he’s not careful. Meanwhile, Louise rushes to get Julie and explain the situation, saying that when the strange man hit her, it felt more like a hug than a slap. A shocked Julie says she knows exactly what her daughter is talking about.

For the first time, Billy seems to have some sense “knocked into” him, too. He doesn’t dialogue over it, nor is there heavy introspection or a song. But at Louise’s graduation, he notices the guest speaker, the beloved town doctor, bears a striking resemblance to the Starkeeper. Heavenly Friend agrees, noting many people like the doctor bear that resemblance, and the two share a brief conversation about Billy’s life, Julie, and Louise. Invisible, Billy puts a hand on Julie’s shoulder and tells her, “I loved you, Julie.” Julie gets the message, tilting her chin and adding a strong, resilient soprano to the closing reprise of, “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” as Billy takes his own last walk offstage. It’s implied his place in Heaven is now secure.

As for Julie, her final joining with the chorus secures something for her, too. She had sung “You’ll Never Walk Alone” before, but only a few measures, before breaking down after finding Billy’s body. Nettie had to finish the solo for her. The second time, Julie’s voice symbolizes that she, along with Louise but perhaps more than her daughter, has become strong. She has grown from naive ingénue to mature woman. She has “walked through [the] storm” with [“her” head up high” in ways few others–Carrie, Nettie, or anyone else–could have. Carousel may have focused on Billy Bigelow as the anti-hero and the one with the most to learn, but it is Julie who lives through the story and sees it through to the “golden sky” at the end.

Subtly Ahead of Her Time

Today’s musical fans might say this is all well and good, but still question the “problematic” messages of Carousel. That is, through Julie Jordan Bigelow, were Rodgers and Hammerstein trying to romanticize if not excuse domestic abuse? Or did they inadvertently sacrifice the innocent Julie for a chance to plumb the depths of Billy’s character, showing the tragedy of a promising young man who let anger, insecurity, and laziness rule his life?

The answer is “neither.” As with Laurey Williams McClain, the story R&H tell about the classic ingénue Julie Jordan Bigelow looks simple and nostalgic, rather like a colorful carousel playing calliope music. But on closer inspection, Carousel is much more complex than it seems. That’s mostly because of Julie, not Billy. Without Julie, Billy and the other characters have no motives, no “center.” They have no character arcs, nothing toward which to grow. Julie herself is not a complicated character, but she forces the other characters and the story itself to ask complicated questions, such as what constitutes real love, what people should tolerate or expect from relationships, and what happens when life disrupts idealistic expectations.

As for the question of tolerating abuse, close analysis reveals Julie tolerates it without accepting it. That is, in her era, Julie did not have the option to “get out.” Domestic abuse shelters, hotlines, support groups, and the like did not exist. However, Julie does speak to changing the status quo in small, quiet, and pointed ways when she can.

As noted, “What’s the Use of Wond’rin” does this in an understated, yet major way, as Julie speaks to the fact that domestic abuse does happen and does continue no matter how many good intentions bystanders have. And while Julie’s reaction to Louise being slapped remains controversial–some of today’s directors do leave it out–the fact that she acknowledges she knows what her daughter means, does speak to how complex that issue is, and what it costs the person being abused.

In any case, Julie Jordan Bigelow is easily the more complicated and better written of R&H’s classic ingénues. She, more than Laurey Williams McClain, challenges not only the ingénue status quo within musical theater, but the status quo of relationships in her era. Both Julie and Laurey, though, paved the way for R&H to write their two dramatic ingénues in later years. Those dramatic ingénues have their issues as well, but are often remembered more positively. Even if not, the two dramatic ingénues are held in high regard and worthy of even deeper discussion than their classic forerunners.

The Dramatic Ingénues: Anna Leonowens and Maria Von Trapp

Not long after the premieres of their classic ingénues, Rodgers and Hammerstein turned their attention to musicals that starred a different type of female lead. These leads were still ingénues, in the strictest sense. However, they were not as naive as characters like Laurey or Julie. They had experienced much more of the world. Their stories pitted them against larger, thornier, and farther-reaching problems than the classic ingénues had faced. These were R&H’s examples of the dramatic ingénue.

The dramatic ingénue, like the classic, is still sweet and kind. In the language of tropes, she may be more a “Blithe Spirit” than her classic counterparts. That is, her presence often introduces or restores light and life to an austere environment. Additionally, the dramatic ingénue probably isn’t sexually experienced. At most, she might be engaged or a widow. She understands more about sex than the classic ingénue. That understanding lets her hold it as special or sacred, rather than romanticizing it or, as the classic ingénue often does, glossing over it as part of an idealized relationship.

Because of her maturity, a dramatic ingénue usually isn’t a “damsel in distress.” Her story may involve an element of danger from men, a competing “vamp” female, or another adversary. But a dramatic ingénue is usually more focused on self-discovery or reaching the next phase of mature womanhood. Her typical character type and voice part usually reflects this. A dramatic ingénue may still fall between ages 18-25, but it’s not uncommon for her to be older, up to mid-30s. A dramatic ingénue is often still a soprano, but unlike a classic, she’s not necessarily operatic or lyrical in tone. Mezzos are not uncommon in these roles, nor are coloratura sopranos, sometimes called “first altos.”

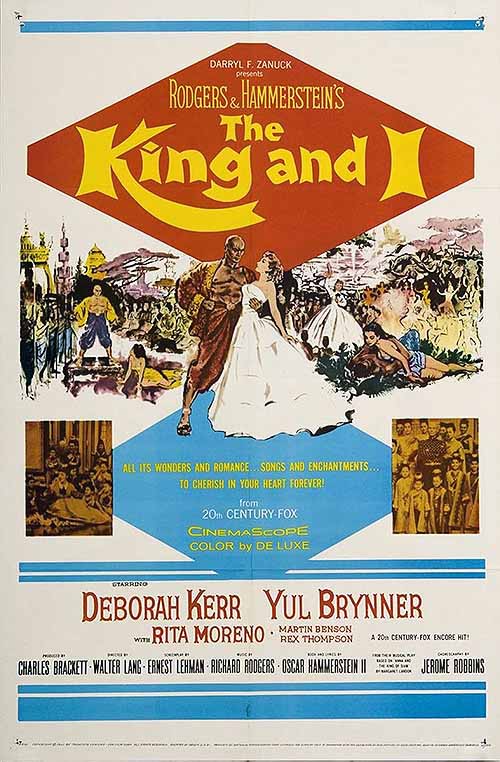

Rodgers and Hammerstein gave us dramatic ingénues in the form of Anna Leonowens and Maria Von Trapp, stars of The King and I and The Sound of Music, respectively. Premiering in July 1956, a mere five months after Carousel, the film version of The King and I starred Deborah Kerr, although it had been playing for five years on Broadway before then. The film version of The Sound of Music, starring Julie Andrews, wouldn’t grace the silver screen until eight years later in 1965, five years after its own Broadway premiere in 1959.

The King and I and The Sound of Music have some debatable advantages over Oklahoma! and Carousel. Since the films feature different lead actresses, their roles are less likely to be stereotyped. Thus, dramatic ingénues playing Anna, Maria, or similar roles are less likely to be typecast (although the role of Maria has become synonymous with Julie Andrews in the 60 years since the film). Additionally, the films’ stories are historically based, if very loosely. That doesn’t protect them from harsh criticism, as we will see. But it does lend these films, and their ingénues, gravitas Oklahoma! and Carousel don’t have.

It can be easier then, to read the subtext behind Anna, Maria, and what R&H meant to convey with their character growth, and the roles of dramatic ingénues in general. Interestingly though, these traits can give the films and their leads a “double-edged sword.” They have more gravitas, but the stories, the women, within idealistic, romantic musicals, are harder to understand and “pin down.” Then again, perhaps that lends R&H more gravitas and more secure places in modern film and theater than 21st century audiences knew.

The King and I: Who’s Teaching Whom?

Oklahoma! and Carousel have had their detractors in the 21st century, but no Rodgers and Hammerstein production has faced the ire of “cancel culture” quite like The King and I. The play and film have been banned in Thailand almost from day one, because making fun of the monarch is a punishable offense. Even affectionate parodies aren’t tolerated. Meanwhile, British and American audiences have excoriated Anna Leonowens and King Mongkut’s story for being “kind of racist…like an elderly relative you make allowances for on the grounds of age,” and a consummate example of “imperial condescension.”

The King and I also gets excoriated, not only in theatrical and film circles but in historical and academic ones, because it falls into the trope Based on a Great Big Lie. That is, a lot of historical fiction takes artistic license with real stories; this isn’t an issue in itself. However, many people have been and are offended at the number of liberties R&H took with Anna Leonowens’ real story, because their musical perpetuated some unusually big lies. For instance, the real Anna wrote in her memoirs of an actual concubine named Tuptim who was tortured and murdered; the real Tuptim was never tortured and lived to be a grandmother. The real Anna also wrote of dungeons in the Siamese palace; this would never have been possible because geographically and architecturally, the palace could not support dungeons. These and other lies, such as the lie that the real Anna spoke fluent Thai, have been said to perpetuate colonialism and the belief that Eastern people, Thais in particular, were “savages” in need of the civilizing influence of white people. Partially because of the R&H musical, this attitude persisted into the late 20th century.

But like its predecessors, The King and I has another, more complex side to its controversial coin. This production works better than Oklahoma! or Carousel because its main characters seem aware of the controversy and complexities within their story. That story is heavily fictionalized, but the leads take it seriously 100% of the time. They know their situation turns on the central question, “who’s teaching whom,” and there is no easy answer. That is, The King and I is not a story of a simple role reversal wherein the would-be “white savior” learns classist and colonialist attitudes are wrong. Nor is it a story in which a strong but “uncivilized” king becomes “kind and gentler” due to an innocent white woman’s influence.

Rather, the central question of “who’s teaching whom” can only be resolved when both characters, Anna in particular, learn what is meant by “teaching.” Anna’s question in particular can only be answered when she finds what she is meant to learn, and what she should do with it.

Anna Leonowens: Bold, Brilliant, and…British

Anna Leonowens catches viewers’ attention from the moment she pulls into port in 1862 Siam. A widow with a son about 10 years old, she’s taking the position of royal governess sight unseen. Although the modern viewer in particular might question her wisdom, it’s impossible not to admire her gumption. In 2025 the most adventurous person, woman or man, would probably hesitate to pack up and move to a foreign country with no apparent plans to return, on the basis of a somewhat non-specific job offer. A single parent would have even more reason to hesitate.

In 1862, such a move would be unheard of for a woman and practically scandalous for a single mom. Anna Leonowens has done so while fostering courage and optimism in her son, barely flinching at a half-naked Siamese prime minister, and in her words “[knowing] no one in Bangkok at all.” This is no teenager looking for a picnic date or sheltered mill girl chasing trouble. This is a grown woman with concrete goals and the relatable need to provide for herself and others. Viewers know Anna is in for significant culture shock, but they follow her out of empathy, not pity or concern that she’s in imminent danger. They know they, too, would experience culture shock and want to see how this woman who literally whistles at danger will handle it.

Anna handles the culture shock well until she finds out she’s expected to live in the palace. Per a written agreement with King Mongkut though, she was promised a house of her own adjoining the palace. “A brick residence” was the exact phrase used in Mongkut’s letter. Anna immediately determines to resolve this issue. She feels separating herself from the palace will give her more freedom to bring up her son Louis “as his father would’ve wished.” Just as importantly, she knows the Siamese custom of polygamy and doesn’t want Louis exposed to the harem. Thus, she marches straight into King Mongkut’s throne room, ignoring protocol. When the prime minister, or Kralahome, warns, “King in bad spirit today. Suggest schoolteacher wait for better day,” Anna retorts, “My spirit is just as bad, Your Excellency, I cannot wait!”

Fortunately for Anna, Mongkut is taken aback but ultimately too intrigued to be angry about her presumption. For her part, Anna continues in said presumption because she finds Mongkut offensive. When he asks personal questions about the death of her husband, she calls him on it, unaware that in Siam, asking personal questions shows concern and kindness. When Mongkut asks her age, Anna calmly states, “I am 150 years old, Your Majesty.” Impressed that Anna could so quickly do the correct math, but not to be outdone, the king presses, “How many grandchildren shall you have by now?” and when Anna can’t answer immediately, laughs, “I make better question than she make answer!” The court laughs with him, the ice is broken, and Anna and Louis are welcomed into their new lives.

Royal Interactions 101

Anna drops the house issue and viewers relax with her, partially if not mostly because she’s still standing after daring to interact with Mongkut as she did. However, this first interaction brings up some points about Anna’s trajectory. Specifically, as a British woman, she would’ve known the basics of royal protocol, if not protocol specific to the Siamese court. Therefore, she arguably should have known better than to act openly offended, or to approach Mongkut at all. The implication is, she only did so because right now, she privileges Britain–thus her worldview–over Mongkut’s. Her attitude, and her words about the house, indicate Anna believes she is in fact in Siam as a “civilizing” influence, that Siamese customs and people are beneath her.

Anna’s first interactions cement her standing as a dramatic ingénue, emphasis on “ingénue.” She has proven much smarter, bolder, and calmer in a crisis than our first two ingénues, which will serve her well. Viewers can infer widowhood and the expectations, perhaps marginalization, thereof, have forced her to speak out more than a “proper Englishwoman” of her era should. The fact remains though, Anna has undergone a huge shift in country and culture. She has plenty of “book smarts” but lacks any “street smarts” that will translate to an Eastern royal court. Some of her British values may be appreciated, even needed, in her new home. Yet she will have to learn alongside Mongkut’s wives and children, and be a much more diligent student, if she wants to survive physically and more importantly, emotionally.

Anna proves a quick study when it comes to her governess position. She ends up with a classroom full of Mongkut’s 67 most promising children, including the heir, Prince Chulalongkorn. She’s also surprised to learn she’ll teach several wives and concubines, including head consort Lady Thiang and newest concubine Tuptim. Anna, however, accepts this much more easily than she did the idea of living in the palace. She easily charms her students with the famous song “Getting to Know You,” noting she is learning as much about and from them as they are from her. She finds teaching fulfilling too, although it can get chaotic, as when she tries to explain Siam’s real size in relation to the rest of the world. The children, who have been taught Siam is the biggest country in existence, are confused and offended, and the lesson devolves into shouting and jumping around.

Anna has mixed results with other lessons of various subject matter. The children are fascinated when she explains snow, but the little ones declare they “do not believe such thing as snow” when Chulalongkorn expresses his doubt. On a more serious note, Anna continually sneaks reminders of Mongkut’s promise of a separate house into her lessons. For instance, she teaches her class the song “There’s No Place Like Home” and has them practice their handwriting with sayings like, “East or west, home is best.” Every time something like this occurs, Mongkut either grumbles against Anna’s teaching or disrupts her lesson. Sometimes Anna diffuses the situation. At other times, she digs in her heels, as when Mongkut declares he does not remember promising her a house–does not remember anything, in fact, except that she is his servant. “I am most certainly not your servant,” Anna retorts in front of the wives, children, and Kralahome.

Nothing erupts. but the tension between Mongkut and Anna increases. It almost reaches critical mass when Mongkut discovers Anna has given Tuptim her copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. When he learns what the book is about, and that Chulalongkorn has questioned slavery, Mongkut warns Anna she is overstepping her place. “Prince Chulalongkorn is a fine boy with a keen mind,” Anna responds. “But he has much to learn, Your Majesty.” Mongkut walks away looking disturbed, perhaps to puzzle this out. Meanwhile, the Kralahome warns Anna she is in dangerous waters. “Inside [King Mongkut] is strong king like his father was who cannot change,” he insists. “He will only tear himself in two trying to be something he can never be.”

Trusted Ally or White “Savior?”

Anna doubles down, insisting Mongkut can become both the “civilized” monarch on good terms with the West he idealizes, and the strong Eastern monarch who will meet Siam’s expectations. Unlike Laurey or Julie, she’s not being completely naive here. She regularly sees evidence that Mongkut wants this outcome. Soon after her confrontation with the Kralahome, for instance, Mongkut calls for Anna, insisting she dictate a letter to President Lincoln for him. In said letter, he offers to send America an army of elephants to help Lincoln win the Civil War. This mushrooms into a discussion on the zoological nature of elephants, science, the Bible, and creation, all of which Mongkut studies and debates with relish.

Anna finds the situation bemusing and frustrating, especially since she must honor court protocol at 2:00 AM while fully dressed–“Moses! Lincoln! Elephants! Groveling on the floor at two o’ clock in the morning!” Yet she enjoys the conversation itself, despite Mongkut “trolling” her, changing his position every few minutes so that Anna must change hers, adhering to the rule that no head shall be higher than the king’s. For the first time, she accepts Mongkut as a ruler with national problems on his shoulders, as seen when she takes his letter to Lincoln seriously. She’s also learning she need not prove her point or be “correct” every time she and Mongkut interact. She could have easily argued for creationism, for instance, but focuses on the relationship between science and faith.

Thus, Anna passes her first few “quizzes” in royal interaction, and Mongkut begins seeing her not only as a Western curiosity and means to “civilizing” his country, but a trusted friend. Yet Anna still has work to do if she means to pass a real test. At this point, she still condescends to Mongkut and many of his efforts both to understand the West and rule his country independently. Check her surprised, overly kind tone when she exclaims, “Oh, Your Majesty is reading the Bible” (emphasis mine). See also her insistence that Mongkut is “certainly not” a barbarian when he expresses his worry of other countries thinking so; she sounds much like a parent consoling a child who worries about monsters in the closet. Additionally, while Mongkut and his court learn plenty about Western geography, religion, science, and literature, viewers never see Anna returning the favor, despite being surrounded with opportunities via the Siamese language, Buddhism, Siamese architecture, and so on.

Anna’s imperialism is true to her era and an important part of her arc as a dramatic ingénue. She must face her own prejudices if she’s to face her central question with any level of maturity. But by the end of Act I, she is still not ready for this step or all its implications. She agrees to help Mongkut throw a lavish European ball for visiting dignitaries, in hopes they will see the Siamese monarch is “not a barbarian” and Siam does not need to become a European protectorate. While Mongkut undertakes this project for the good of his country, Anna sees it as a chance to help or even “save” Mongkut from “backward” ideas like polygamy and slavery. When tested however, Anna may be the one who needs saving.

Comedy, Tragedy, and Intimacy

As Act II begins, the Siamese court eagerly prepares for its British visitors, the European-style dinner party, and Siamese-style entertainment, a play featuring mostly silent actors and Tuptim as the narrator. There are a few glitches. When presented to the king, the wives and concubines bow facedown as usual, lifting their voluminous skirts and exposing an oversight. Siamese women do not generally wear undergarments. Anna has to explain knives and forks are preferable to chopsticks, leading Mongkut to agree, “I make mistake. British not scientific enough for use of chopsticks.” And when bearded British ambassador Sir Edward Ramsay arrives with his monocle in tow, one of the wives screams, “He has the head of a goat! He will eat us all!” Mass hysteria ensues, and Anna and Lady Thiang must do emergency damage control.

These moments aside, the dinner goes off well. Mongkut relaxes in the knowledge that his visitors are impressed with both himself and Siam. The dignitaries find his children particularly charming, and although he might feel a hint of jealousy when Edward pays special attention to Anna, the production doesn’t linger long enough for viewers to tell for sure. The atmosphere tenses when Tuptim announces her play is called “The Small House of Uncle Thomas,” but the visitors seem entertained. Additionally, Mongkut seems placated since it’s presented in a Siamese format and since the villain, Simon Legree (“King Simon of Legree” here), bears no resemblance to himself whatsoever. This “king” is more a caricature villain, complete with an exaggerated traditional mask, using the title “king” more like a label.

Everything almost falls apart near the end of the play. By then, some of the protagonists, “King Simon’s” escaped slaves, have died. Though they are shown to go to Heaven with Buddha, Tuptim cannot ignore the injustice. She breaks character and exclaims she hates this king, hates any king who would keep slaves who are unhappy. She turns to Mongkut and begins, “Your Majesty, I ask of you, I beg of you…” A ringing gong brings her back to reality, and she finishes the epilogue as written before Mongkut can lose his temper or anyone else can catch on to what almost happened. The ensuing ending is a bit awkward, but joyful, and noisy enough for Tuptim to slip out. Anna, who knew all along what Tuptim meant to do, distracts Mongkut and the audience long enough to give her a head start.

Viewers know Tuptim has escaped her own slavery in hopes of being with her lover Lun Tha, whom they briefly met in Act I. Anna facilitated the meeting and now lets Mongkut draw her into a discussion about her views on relationships, romantic and platonic. Anna doesn’t share any of the complex feelings she’s experienced in Siam, from poignant memories of her husband, to confusion when Edward expressed romantic interest. She doesn’t dare admit her need to see Tuptim and Lun Tha find happiness and justice in a country whose systems don’t allow it. But when Mongkut invites her to show him the proper European way to waltz–“not holding two hands,” with his arm at her waist–Anna obliges. The waltz becomes a lively yet romantic polka.

Anna cannot and will not become Mongkut’s lover. That would be based on infatuation, impractical, and probably illegal. Yet the dance’s subtext indicates Anna finally sees Mongkut as her equal. She has come alongside him to secure Siam’s respectability, thus, the respectability of the royal family. Anna has also given Mongkut more emotional intimacy than ever before. Most telling, their dance lets Mongkut come as physically close to Anna as possible without causing a scandal. These factors make it all the more devastating when the Kralahome interrupts the waltz to announce Lun Tha is dead and Tuptim has been tracked down. The girl is thrown to the floor, and Mongkut orders her flogged in front of Anna.

Dignified Death, Promising New Life

Anna will not stand for this decree. Echoing Tuptim’s words, she exclaims, “Your Majesty, I beg of you, don’t take revenge on this girl. This girl hurt your vanity, that is all. She didn’t hurt your heart!” Had Anna left her indictment there, the confrontation might have ended fairly well. Mongkut might have rethought his actions or at least walked away to stew as before. But this time, Anna overplays her hand, adding, “You have no heart! You are a barbarian!” Gutted, the king freezes, whip in midair, before throwing it down and rushing from the ballroom.

This is where Mongkut and Anna’s story, and Anna’s trajectory, get tricky. All debate about colonialism aside, Mongkut’s engagement in slavery is wrong. Rodgers and Hammerstein hint he knows it, via his fascination with President Lincoln, his son’s struggles, and his inability to punish Tuptim for any of her words or actions. Further subtext adds disapproval of Mongkut’s polygamy and condemnation of his possessive nature toward Tuptim. Viewers can hardly blame Anna when she determines to leave Siam for England. She’s rightly devastated and considering her widowhood, is probably doubly traumatized from desire to accept a new culture warring with imperialism–confusing schemas similar to what Mongkut has experienced.

Still, viewers might wonder if Anna is actually running away. After all, she has engaged the same ship from her journey to Siam, and as before, both her decision and preparations appear unusually quick. And when Anna learns Mongkut is dying, she has a convenient reason to leave right away. With the king dead, she has no “loose ends” and a concrete source of hardship to blame, should anyone in England ask what happened or cast aspersions on her controversial actions.

There are only two things saving Anna from looking immature and foolish here. One, Mongkut himself has sent for her. Two, she loves his court, especially the children, enough not to leave without a proper goodbye. In other words, the white, British, imperialist governess has made a decision based not only on Siamese protocol, which is learned through “head knowledge.” She has made a decision based on ever-growing love for Siam as a country, and its people.

Long Live the King…And Anna

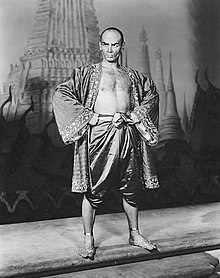

It’s never stated why Mongkut is dying, although some productions clarify he contracted malaria at some unseen point in Act II. Other productions, including the R&H film, hint that the rigors and expectations of rule placed too much stress on a body that was already approaching middle age (Yul Bryner was 36 in the role and could have easily been “playing older”). At any rate, King Mongkut is barely able to speak by the time Anna reaches his side. He speaks well of her and implies absolution for Tuptim, but spends much of his limited time installing Chulalongkorn as king. Chulalongkorn has prepared, asking his father if he can make a proclamation. “Yes, make it, make it, make it,” Mongkut whispers, his signature triple order underscoring the seriousness of the moment.

Chulalongkorn surprises everyone, speaking of respect for both his father and “Mrs. Anna.” Out of respect for both, he says, “there shall be no more bowing,” in the fashion of “crawling along on the ground…like turtles.” Instead, Chulalongkorn proclaims, people will stand before their king with pride and dignity. Mongkut agrees, echoing, “There shall be no more bowing, or showing respect for king.” But the way he says “respect” indicates his perspective on the word may have changed. Nothing in the R&H narrative shows Mongkut ever accepted any of Anna’s views on the monarchy. But viewers are meant to understand he dies in peace. Given the rest of the story, this would only be possible if he had made peace with the Western and Eastern ideals warring inside himself.

As for Anna, she has made peace with her own warring ideals by the time Mongkut dies. As her father breathes his last, one of the youngest princesses, Ying-Yowalak, approaches and reads Anna a heartfelt letter. In it, Ying-Yowalak speaks for the royal children, highlighting all they have learned from “Mrs. Anna” and imploring that she stay and continue to teach them and “lead us in right road.” Again, there is no clear privileging of Western or Eastern philosophy. Even if there were, Anna neither would nor could revolutionize the Siamese monarchy. But the plea does convince Anna to stay in Siam, not to civilize anyone, but because she sees the palace as a true home and the children as a family.

Anna’s decision to stay concludes her dramatic ingénue arc. By the end of The King and I, she is still kind and relatively innocent, at least sexually and sensually. She still has much to learn about Siam and its people. But she has faced and won against external and internal dangers. She has answered a vital central question regarding her role as a teacher, what she needs to learn, and from whom. Most importantly though, Anna has fulfilled the role of dramatic ingénue because she has discovered a huge part of herself. She has learned how her small story can affect a larger sphere, whether that’s a family, a palace, or an entire country. And while the real Anna Leonowens’ story may not be as idealized as The King and I, R&H’s fictional version still has much to offer in the form of a governess “getting to know” the wider world.

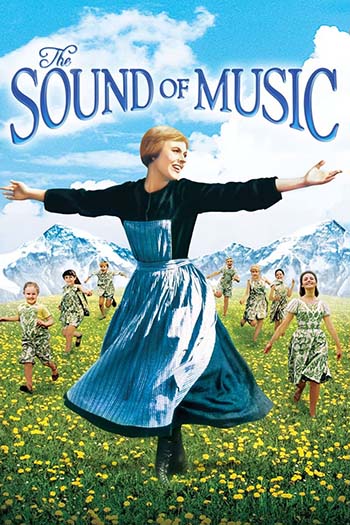

The Sound of Music: Crown Jewel, Ingénue Queen

The Sound of Music comes last in our discussion, not only because it is chronologically “last” with a 1959 Broadway run and 1965 film, but because it is Rodgers and Hammerstein’s best-known musical. It has been called “the most popular movie musical ever made,” per the Time Life advertisements that once sold the entire R&H collection and featured The Sound of Music as its crown jewel. This musical so inundates American culture, it’s difficult to find a high school, college, or community theater in a town with any significant population that hasn’t produced it.

It’s referenced constantly in contemporary film, television, and literature. Many of its songs have “crossed over” into other genres; celebrities from Michael Bublé to Kelly Clarkson have covered “My Favorite Things” at Christmas, and elementary music teachers use “Do, Rei, Mi” to teach their students basic sight-singing skills. “Climb Ev’ry Mountain” is often sung at high school graduations, and girls named Maria often react to the eponymous song with affection or chagrin.

The Sound of Music is also the only one of the four musicals we’ve discussed that has escaped the amount of controversy overshadowing the other three. It does have detractors. Critics claim its portrayal of Nazi-occupied Austria is too heavily romanticized and the “good vs. evil” conflict is too simplistic. Christopher Plummer, who played Captain Georg von Trapp in the film, found it “insipid and nauseating.” The real Maria von Trapp initially hated the idea of signing the rights to her story away to Hollywood, and ended up hating the way the movie portrayed her husband, in particular. Many audience members find The Sound of Music sickeningly sweet and the musical numbers overdone and “mawkish.”

As with the detractors of our other musicals, detractors have a point, particularly those who criticize The Sound of Music’s portrayal of Nazi-occupied Austria and its failure to pay proper respect to targeted minorities like the Jewish people. However, even in the 21st century, that controversy tends to be eclipsed. At most, it is balanced more evenly with accolades from fans, both nostalgic and new, than in the cases of the other musicals we’ve discussed. As with other R&H musicals, the reasons why depend on who you ask. However, much of The Sound of Music’s staying power could be encapsulated in Maria Von Trapp, her character growth, and how she deals with her personal central question.

Maria Rainer Von Trapp: Searching for a Calling

The real Maria was born Maria Kutschera in Tirol, Austria in 1905. To separate the real woman from the fictional, the stage version gives Maria’s maiden name as Rainer, while the film doesn’t specify. In all versions, Maria is a young Catholic postulant hoping for full acceptance into Nonnberg Abbey “in the last golden days of the thirties.” She has struggled with the strictures of cloistered life from day one. The song “Maria” expounds on transgressions including climbing trees, tearing her clothes, wearing curlers, and chronic lateness. She sings constantly, even when she shouldn’t (the offended novices don’t see the irony of singing about Maria’s sins, inside the abbey, no less). Many nuns, including Mistress of Postulants Sister Margaretta and the Reverend Mother herself, have urged patience with Maria. She knows what’s expected of her, wants to do well, and never means to break the rules. But although viewers don’t know how long Maria’s been at Nonnberg, it’s clear she won’t be fulfilled living the life of a cloistered nun permanently.

The problem is, Maria thirsts for a calling. Note this is different than “purpose.” Maria is a devout believer in God and the Catholic faith. That faith places much emphasis on one’s vocation and what one can do for and with God to further His kingdom. The fictional Maria’s devoutness is never explored, but a look into the real Maria’s life gives the fictional character deeper shading. As Peter Graves explained in Biography’s episode on the real Von Trapp family, Maria Kutschera was orphaned as a toddler. Her only living relative was “an elderly uncle, who beat her constantly, whether she behaved or not, and young Maria never behaved. She played hooky, lied compulsively, and…was always in trouble” when she showed up at school.

Graves doesn’t specify whether Maria acted out to get attention or because of her pain, though modern viewers can infer a combination of both. He does say that, though raised Catholic, she went to church more for the music than the homilies. But during young adulthood, she was convinced to attend confession. Afterward, she felt such relief and joy, she craved more of God. That “emotional high” never wore off. It bloomed into conversion, and Maria Kutschera entered an abbey just like her fictional counterpart. Like her fictional counterpart, she had trouble adjusting, though in Kutschera’s case, this was due to poor health and a tendency toward real incorrigibility. The real Maria was said to tell people the movie toned her down.

Viewers can presume the fictional Maria’s backstory is similar. They hear nothing of a biological family. Maria is young; Julie Andrews was 29 in 1964, and her character is supposed to be younger. So perhaps Maria still feels orphaned as a young adult, or was even orphaned recently. Perhaps she entered the abbey partly because she didn’t feel she fit into the wider world. Speculation aside, it’s clear Maria believes God has something particular for her to do. It is her mission to “find out what is the will of God and to do it wholeheartedly.” This dramatic ingénue begins her story believing that is her central question: What exactly is the will of God? More specifically, what is my calling within the will of God, and can I give it my whole heart? After all, Maria wants to do this. But painful experience has taught her, just because she wants to succeed doesn’t mean she will. If anything, she’s failed spectacularly so far.

Can’t Keep a Good Governess Down

When Reverend Mother calls Maria to her office after the latter shows up late for morning chapel–again–it seems Maria has spent her last second chance. Indeed, Reverend Mother plans to send her away from Nonnberg, which Maria pleads with her not to do. Reverend Mother clarifies this is not discipline; she thinks Maria could benefit from self-reflection and being out in the world. When Reverend Mother explains a local family with seven children need a governess until the coming September, Maria is aghast. “Seven children!” she exclaims. Reverend Mother is gentle, yet holds firm, reminding Maria she likes and is good with kids, and will know for sure what her calling is after this time.

Given no other choice, Maria leaves Nonnberg, and finds herself excited about being “out in the world [and] free” again. In the film, she uses the solo “I Have Confidence” to psyche herself up about becoming a governess. Seven kids aren’t so fearsome, she reasons. As long as she faces the challenge with courage, honesty, and optimism, she will show the von Trapps and herself she is worthy of regard. Yet that optimism is shaken when she meets Captain von Trapp, who literally bursts in on her as she practices an overblown introductory curtsy in his deserted ballroom. “In the future, you’ll kindly remember there are certain rooms in this house which are not to be disturbed,” he chastises. The Captain goes on to criticize Maria’s clothes, and before she can absorb that, calls for his children with a series of military whistles. The children march downstairs in order from oldest to youngest, wearing junior military uniforms. Each has a personalized “signal”; when their father sounds it, they march forward and snap their first name as if in a drill.

Captain von Trapp starts to give Maria her signal, but much like Anna Leonowens, Maria cuts in. “No, sir, I’m sorry,” she shouts over the whistle. “Whistles are for dogs and cats…but not for children and definitely not for me. It would be too humiliating.” The Captain tries to insist, citing the house’s “extensive” grounds as a reason for the whistling. But Maria digs in her heels, leading the Captain to ask with a little smile, “Were you this much trouble at the abbey?” Assured she was much more, the Captain barely knows how to respond. As it is, he can only leave Maria alone with the children. His stern, silent exit might communicate Maria has failed again. Yet the childish giggles in the background show she’s won a small victory.

Maria takes the opportunity to let the kids reintroduce themselves, share their ages, and build rapport. The youngest two, Marta and Gretl, seem eager to let her in. The older kids are wary; oldest son Frederick drops a frog down Maria’s blouse in a bid to get her to leave. Later on, someone plants a pinecone on Maria’s chair at dinner, which disrupts the ever-formal occasion. But considering how everyone starts crying after Maria asks Grace, the majority of von Trapp children have rethought their strategy with this governess.

Storms and Sunshine Ahead

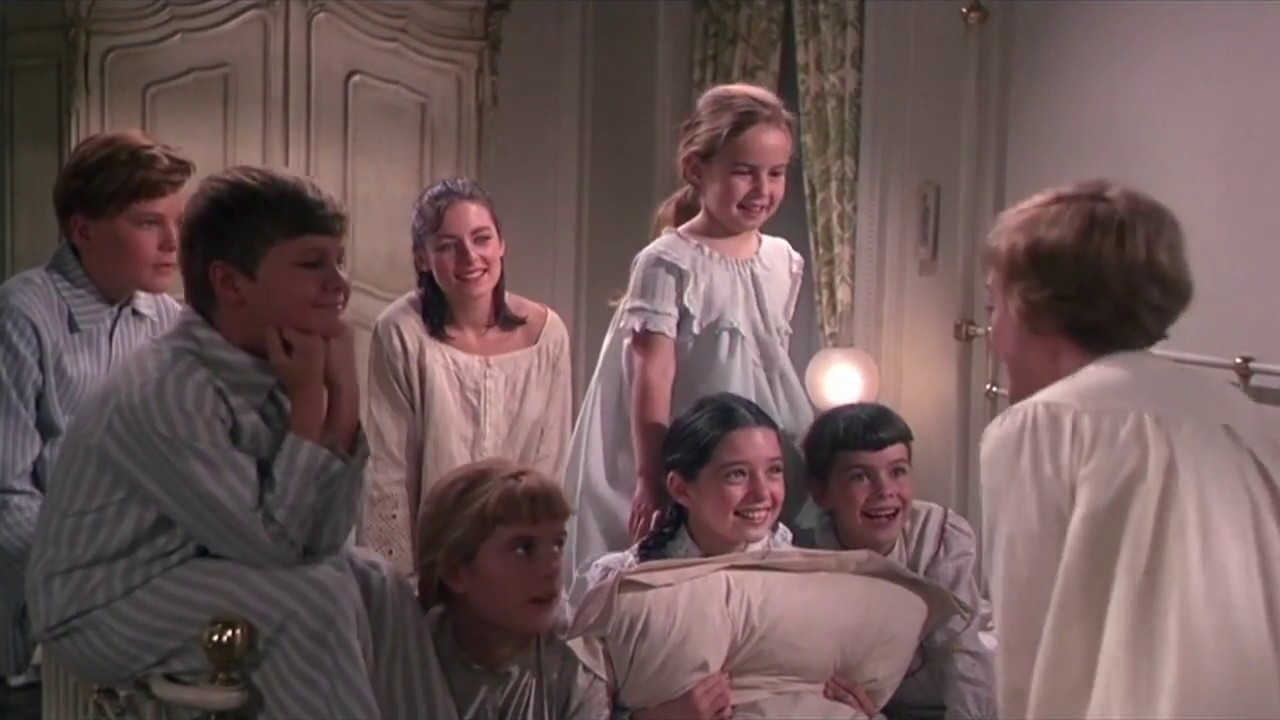

Maria cements her bond with the kids later that night. She loans Liesl a nightgown and listening ear when the latter sneaks into her room after a secret date with the telegraph boy, and a run through a thunderstorm. A frightened Gretl runs into the room while Liesl is changing. Maria scoops the little girl up and says, “You just stay right here with me.” When Gretl expresses chagrin that the others aren’t scared, Maria corrects her; her three other older sisters have rushed in as well. The governess invites everybody to join her on the bed, and expertly covers for Kurt and Frederick when they seek solace, claiming they were checking up on the women and girls.

The famously cheery “My Favorite Things” ensues, thunderstorm fears forgotten as everyone sings along, adding contributions from Christmas and bunny rabbits to chocolate icing, no school, and from an emerging Liesl, telegrams. Frederick adds “pillow fights,” which touches off a choreographed one during the song’s second run-through. Mid-chorus, Maria almost crashes into Captain von Trapp, whose presence has his children scrambling back into a precise line. Undaunted, Maria assures the Captain she only forgets his rule about “strictly observed” bedtimes during thunderstorms, and warmly sends the now-reassured children back to bed, after smoothly covering for Liesl, with whom she had allegedly “been getting better acquainted.” But when the Captain refuses to give Maria the material to make play clothes for the children, and by implication allow them free time, she nearly loses her temper.

The Captain’s impending two-week visit with longtime love interest Baroness Elsa Schraeder and Maria’s creativity with some unwanted drapes keep our ingénue’s mind off the confrontation, and any emotional danger she might be in. With the Captain ensconced in Vienna, she takes the children on a sightseeing tour of Salzburg, makes them picnics, and encourages them to play outside. One crucial day, she suggests they think of something to sing for the Baroness. Marta informs Maria the von Trapps don’t know how to sing. Maria wastes no time [“starting] at the very beginning” and teaching vocal music basics via “Do, Rei, Mi.” By the time the Captain comes home, the von Trapp children are well-versed in vocal music and Being Kids 101. Dad, their Uncle Max, and the elegant Baroness spot them climbing trees on the outskirts of Salzburg, practicing solfège in the process.

Emotional Tension Crescendos