Spirited Away as Social Criticism

Spirited Away is a vibrant coming-of-age story rich with the imagery of Japanese fantasy. It tells the story of the protagonist Chihiro’s disappearance from the human world, and her maturation as she starts working at a demonic bathhouse. While the movie was a huge hit, both in Japan and abroad, there has been hardly any detailed analysis of it.

Broadly speaking, Spirited Away is a movie about coming of age in a time when the world is becoming less caring. The facts presented to the viewer about Chihiro’s world are that she was forced to leave her friends behind, presumably because her already comfortable parents found a better economic opportunity. It’s also a time of environmental loss: development in Japan has annihilated the Kohaku River whose spirit once saved a drowning Chihiro. Because the human world has largely abandoned her, Chihiro is forced to find comfort in the unlikeliest of places: a demon-run bathhouse. Thematically, the movie deals with the growing cruelty of the human world, but there’s clearly more going on than that: looking at a couple of scenes, like the Stink Spirit or the parents’ transformation, it’s easy to argue that the movie takes a pro-environment or anti-consumerist stance, but what are the underlying mechanics that allow for such social commentary?

Hierarchy of the Bathhouse

Understanding the corporate structure of the bathhouse is an important first step to reading the social commentary of the movie. Noriko Reider acknowledges a hierarchical order to the bathhouse, pointing out that Yubaba literally lives at the top, with the other workers (but specifically Kamaji) living below her. The bathhouse wouldn’t succeed as an enterprise without Yubaba calling the shots: “In Spirited Away, Yubaba is paralleled to the central authority ruling the bathhouse from the top of the building, and Kamaji is likened to tsuchigumo who live in the pit dwelling, or bottom floor” (Reider 15). In her piece on the movie, Reider focuses on how Miyazaki incorporates various supernatural figures from Japanese tradition into the movie’s characters. Kamaji, the gruff spider-like man, is reminiscent of the tsuchigumo, or earth spider. Reider says that the earth spider is historically a representation of people outside of the control of the emperor. Their unwillingness to submit places them at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Reider’s recognition of a clear hierarchical order to the bathhouse is key to the idea that the movie is a parody of Japanese Confucian order: instead of the emperor or some other virtuous leader at the top, it’s demons all the way down.

Japanese Demons

The actual order of the bathhouse exists somewhere at the crossroads of two concepts: the first, the place that demons take in the world of the people who believed in them, and the second, the idea of what is needed to maintain or tear down the proper Confucian order. Regarding the first, Mori Masato writes, “That which we call ‘demon’ is the concrete manifestation of the chaos which was conceived of as being outside order” (Mori 157). Furthermore, he writes:

“Demons were … invisible, and lived in an invisible dimension. By ‘invisible dimension,’ I mean a dimension of chaos which was not illuminated by the light of human civilization, a world of confusion that human consciousness could not encompass.”

(Mori 157)

While Mori is talking in terms of the Konjaku Monogatarishū, an anthology of mostly moralistic Buddhist tales written about a thousand years ago, it’s fair to say that the mindset he is describing fits with the portrayal of demons in Spirited Away. The bathhouse exists on the periphery of the human realm, on the grounds of an abandoned amusement park that Chihiro’s family crosses into through a long, dark tunnel. When they stop their car, the family really does reach the far limits of human society.

The Rectification of Names

But if demons exist outside of the Confucian order, then what exactly is the order they are in opposition to? Loy Hui-Chieh defines one aspect of Confucian order, the Rectification of Names, which given Yubaba’s tendency to steal names from her would-be employees, seems particularly relevant:

“As it is, the teaching of 13.3 can be stated simply: there are forms of incorrect naming and speaking that can lead directly to socio-political disorder, such that any attempt to reinstate order in the socio-political realm must begin with the imposition of order on the linguistic realm.”

(Loy 35)

Yubaba’s name-theft is a direct assault on Rectification of Names, changing “Chihiro” into “Sen” and “the Spirit of the Kohaku River” into “Haku.” Visually speaking, Yubaba transforms the physical shape of their names, contractually binding them to servitude. In doing so, she clearly goes against the Confucian doctrine, which being a demon, is her nature. But something interesting happens here: by taking apart their names, she actually is creating laborers under her command, reemphasizing her centralized authority over the bathhouse. The destructive act becomes a creative one. Here is the crossroads, where the circle of two seemingly contradictory concepts is squared.

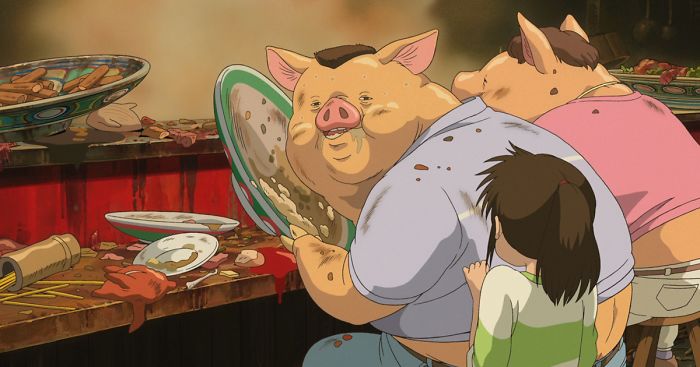

Parents to Pigs

But the robbing of names is not the first major transformation of the movie, and focusing first on it risks overlooking a different episode, the metamorphosis of Chihiro’s parents into pigs. Upon entering the theme park, the family stops at a seemingly abandoned food stand with all sorts of meats waiting to be feasted on. Chihiro leaves her parents to their gluttony. When she comes back, she finds that where her parents once sat are now disgusting pigs. How does this scene exemplify this destruction and reassertion of authority? At once, the chaotic act of transforming Chihiro’s parents into pigs is the corrective act of showing them as they really are, small-minded consumers. They slide right into the bottom rung of the bathhouse’s socio-political hierarchy, becoming the source of sustenance on which the rest of the order depends.

Confucian Parody

Using the structure of Loy’s definition of Rectification of Names, there exists in Spirited Away forms of correct shaping that can lead directly to socio-political order. This order is often temporary and done without planning, but its spur-of-the-moment nature is simply reflective of the dispositions of the enforcers of that order, the demons themselves. And so, in Spirited Away, Miyazaki creates a kind of order where there ought not be one, an order that could be called the Rectification of Shapes, or the idea that order comes from everything being shaped like their nature would have it. This new doctrine establishes a parody of Confucian order that is inherently demonic because it is subject to the chaotic, unpredictable whims of the demons that construct it.

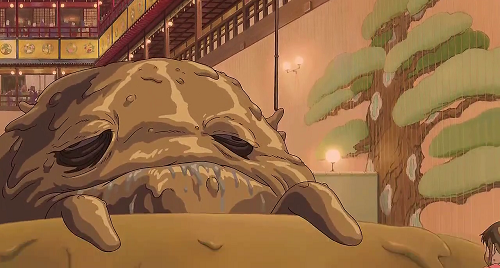

The Stink Spirit

The bathhouse itself is a setting ripe for the concept of “Rectification of Shapes,” because, in a sense, that is its function. The bathhouse is a place where demons cleanse and heal themselves. Nowhere is this more evident than in the case of the Stink Spirit. After failing to deny it entry, Yubaba tasks Sen with taking care of the towering mass of junk and grime. With the help of everyone at the bathhouse, Sen manages to remove all of the debris stuck in the spirit, revealing its true form. Using the ideas of human and demonic spaces, it’s noteworthy that humans performed the demonic act of transforming a powerful river spirit into the Stink Spirit, and it was only in the human-style demonic space of the bathhouse that order was restored through the rectification of the spirit’s shape.

Regarding this scene, Susan Napier writes:

“Initially Chihiro herself is the invader with her ‘human stench’ but, by acquiescing to the dictates of the group, she begins to be accepted and ultimately integrates into her new collectivity. The Stink God also appears as an invader at the beginning, its filth and odor threatening everything the bathhouse represents. Its successful cleansing becomes not only a rite of purification but an exercise in recognition and correct identification.”

(Napier 302)

The encounter Napier describes, of “Japaneseness” coming into contact with the “other,” is different from the one described in this article. Nonetheless, the direct parallel she draws between the corresponding “invasions” of Chihiro and the Stink Spirit seems flawed when looking at the movie through the concept of human and demonic spaces. Chihiro’s invasion is that of a human entering a demonic space, while the Stink Spirit fundamentally never transgresses into a world that is not its own. The disruption that the Stink Spirit brings is only considered a disruption at all because Yubaba fails to recognize the Stink Spirit as a rich and powerful river spirit, a paying customer that ought to be exactly the clientele Yubaba is marketing to. Furthermore, Napier’s characterization of the “filth and odor” being at odds with “everything the bathhouse represents” seems mistaken: the bathhouse can’t perform its function as a place of purification without anything to purify. So while Napier and this article both recognize the Stink Spirit episode as being an example of rectification, the reading of the movie presented here actually goes a step further and argues that the “rite of purification” and “exercise in recognition and correct identification” are not two separate results but in fact one and the same. For the Stink Spirit, the act of purification is the rectification of its shape.

The Carnivalesque

To make better sense of the dynamics of Rectification of Shapes, it’s necessary to look at work that Noriko Reider has done separate from the movie. In her career studying the history of oni (Japanese demons), Reider has implemented Mikhail Bakhtin’s ideas of the “carnivalesque,” particularly in the case of Shuten Doji, a tale of the emperor’s strongest warriors defeating an evil demon king who has been kidnapping women from the capital. Reider writes:

“Taking its name from the raucous medieval celebration of Carnival, carnivalesque literature inverts power structures, demystifying and lampooning that which a particular culture holds serious or sacred. The carnivalesque upsets the structures of everyday life by its flagrant violations of class, gender, and religious boundaries.”

(Japanese Demon Lore 31)

The inversion of power structures that Reider notes is immediately applicable to Spirited Away, in which the bathhouse is presided over by the demonic Yubaba. Yubaba’s irreverence for the Rectification of Names puts her in violation of Japanese Confucianism. The power of the carnivalesque is that it’s subversive. It allows for the environmentalist criticism of the Stink Spirit episode, in which humans transformed the spirit into a disgusting monster. It allows for the critique of consumerism, with Chihiro’s father’s memorable line, “Don’t worry, you’ve got daddy here. He’s got credit cards and cash,” presaging his transformation into a pig.

The Problem of No-Face

In a way, No-Face is the movie’s only true demon. As Mori describes demons, No-Face comes from a seemingly invisible dimension, appearing at the boundary that is the bridge to the bathhouse. To analyze No-Face, we have to understand the rest of the movie’s demons as, for all intents and purposes, not particularly demonic. Perhaps they are scarier looking or have more exaggerated features than humans, but they fulfill the normally human roles of bathhouse guest and employee. No-Face is neither. No-Face has no enumerated intentions or personality. It’s conceivable that Yubaba fails to bring order to the devastation wreaked by No-Face precisely because No-Face is entirely amorphous. No-Face’s only inherent quality is a lack of its own identity, and Yubaba’s grasp over others relies on her ability to change their identities. No-Face is only stopped by Sen, whose gift from the river spirit causes No-Face to purge out everything it has consumed, returning No-Face to what is presumably its “proper” shape. After its rampage is quelled, No-Face is sent back deep into the wilderness to live with Yubaba’s sister Zeniba, suggesting that No-Face simply cannot coexist with a human-style establishment.

Does reading Spirited Away through the carnivalesque actually affect how we interpret No-Face? By equating the demons with humans, we’ve already taken a step in that direction. No-Face exposes the weakness of the central authority of the movie, whose only options are to appease it with banquets, and ultimately to sacrifice Sen to its consumption. In the carnivalesque space, no assumptions are made about the demonic nature of Yubaba’s authority. That is to say, Miyazaki is demonstrating the failure of a central authority to stop the threat of this ravenous monster. That the central authority is in the demonic realm doesn’t actually matter. What No-Face actually symbolizes is beyond the scope of this article, but it’s still obviously subversive to see a leader brought to their knees by the threat posed by something unknown and growing.

No-Face is really an intriguing character, and exploring what No-Face might mean to Miyazaki would be an interesting next step in understanding what exactly this movie is. Meanwhile, this article has tried to show that Miyazaki creates a parody of proper Confucian order by inhabiting it with a bunch of demons, an example of Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the “carnivalesque” in action. In doing so, it has coined the term “Rectification of Shapes,” a short-hand name for how order exists in the carnivalesque setting. With this article, it is my hope that people return to this classic with fresh and stimulating ideas, and more thoroughly enjoy a great film.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

This article gives a very well written in-depth analysis of the anime. The topic of social criticism is very well examined by the author. This particular statement made by the author ” Spirited Away is a vibrant coming-of-age story rich with the imagery of Japanese fantasy”, very well introduces the anime and catches the readers attention immediately. I enjoyed the article and will enjoy watching the film again with a new perspective as some points discussed I had not noticed.

Spirited Away really scared me as a kid, not least because I ended up in fostering for 7 months about a year before I watched it, after my mum and dad both got ill and were in hospital at the same time. Mum’s fine now, dad I got to spend a really good extra 10 years with before he passed away (63; had me late).

Chihiro and Haku’s relationship is really interesting to me. I love this film.

Chihiro and Haku’s relationship is platonic. It’s complex yet very simple. They love and care for each other, Haku helped Chihiro and Chihiro wanted to help him back. That’s what best or good friends would do. It isn’t romantic one bit. Zeniba talking to Chihiro about her “boyfriend” referring to Haku is just a joke/tease. This isn’t Twilight or Little Mermaid, it’s just a little girl going on an adventure and meeting and befriending a young river spirit (he’s thousands of years old but he’s young mentally compared to the others but he is mature).

It can be interpreted as romantic love if you’re a child watching it but it could also be interpreted as just platonic love too if you’re a child or adult. I watched Spirited Away like 4 times as a child, twice as a teen and now once as an adult. As a Kid I thought they were romanitcally in love, the concept of romance as a kid is different to an adults, but it also did come off as a deep caring friendship. But rewatching it as an adult, it’s more pure to see it as 2 little kids who deeply care for each other vs they’re in love at such a young age. It’s like Lion King, when Simba and his friend were kids it’s just like that and when it time skips and they’re older, then it’s romance. So maybe if they showed them growing up, maybe Chihiro and Haku would had eventually become lovers.

The theory is that Haku is Chihiro’s brother who gave up his life for her and became the river spirit. So it was brother-sister love

I do agree there is a sense of ‘love’ between the two characters. The problem is ‘love’ can be defined in many ways. There is such a thing as platonic love between two people who are just friends. There is romantic love. There is familial love. And I believe Chihiro and Haku fall somewhere between either platonic or familial.

Spirited Away is not an anti-capitalist story. It’s a story which shows the problems we as a whole (humanity) have brought to ourselves. Overconsumption isn’t a result of capitalism or free market, it’s a humanitarian issue, a crisis in our values. The narrative isn’t trying to go against a certain political/economic ideology, it is a story about how people need to embrace their inner strength and grow morally and spiritually. This growth can help elevate our societies from the bad situation they are right now.

I agree that it’s not an anti-capitalist story, but I think there are important differences between “anti-capitalism” and “anti-consumerism.” I think it’s hard to argue that the film isn’t anti-consumerist, given the way it depicts the parents turning into pigs and how disgusting No-Face becomes. Anti-consumerism is a criticism of the way members of a society behave, not of its actual political or economic system.

Yes ! YES ! yes! The movie is about a growth of a young girl who was immature and bratty. Through the venture of suffering solo and wanting to survive. She went through growth to know what to do and how to find her true strength. Which is why the ending is so special. Her parents not recalling anything and still treating her as the same as before. When in the meantime she was able to walk back through the tunnels without no complain. It signify her maturity as a youth.

hayao miyazaki is a marxist. the film is pretty explicitly an anti-capitalist critique of japanese consumerism

Any “crises in our values” come from the economic superstructure, “problems” don’t materialize out of thin air. Like another commenter said- Miyazaki was (in his youth) a marxist. Overconsumption certainly isn’t unique to capitalism (take kings and feudal lords for example), but it is a product of economic inequality, which capitalism has not solved for us and can not solve

Love Spirited Away. I haven’t watched since it’s release.

Hayao Miyazaki created this movie to express that we’re alive thanks to others.

Then why do several news articles say Miyazaki used certain images to critique western capitalism?

This was really cool to read, I’ll have to watch the movie again with all this in mind.

Reading your piece made me think, the bathhouse is similar to the house in Carl Jung’s dreams in which the top floor was beautiful and lavish, and the bottom floor was more primal, resembling a cave, and all the floors between were varying degrees of this same descent. He thought the house represented one whole psyche, his own, with each floor representing a different part/layer. I think Yubaba’s office definitely had the same feel as the lavish top floor of Jung’s dream house, while the boiler room in the movie was similar to the cavernous basement of his dream house. I’ll have to pay more attention to the floors in between in the bathhouse to get a better feel for those next time I watch.

This is a very thorough analysis of Spirited Away. I particularly love that it goes past the obvious themes of environmentalism and the like and analyzes the story in a uniquely Japanese (or East Asian) context. I hadn’t thought of the story as relating to Confucianism or what it means to live in an “ordered” society, but when you spell it out like this, it does make sense.

Film characters are based on societal stereotypes, and stereotypes always hold some truth – this is basic narrative theory.

Omg!!! I’ve watched Spirited Away at least a dozen times. It’s always been this beautiful mystery to me… just like life. Your article is incredibly thought-provoking and layered with so much meaning, like the masterpiece, Spirited Away. Much gratitude to you for writing this piece. Outstanding work!

And yes, I’ll be watching Spirited Away again. this time with a fresh set of eyes. Thank you.

Great work. I will watch Spirited Away again.

Kids don’t act like kids in many movies. Spirited Away gets what kids are like in a way few movies do. They’re complex, conflicted, selfish, selfless, enduring, tiring creatures. And that’s how the protagonist of Spirited Away is portrayed. But it’s more than that. Kids are willing to learn. They want to be better. And in Spirited Away, we see her get better, become more introspective, be more observant, and learn how to deal with a complex dynamic of authority figures. You just don’t see this in many other movies. Spirited Away is one of the most fantastical films ever made but it’s also one of the most realistic. It understands what being young is like.

It is not my favorite of Miyazaki’s film, but it’s one of his best.

What I like about a lot of Miyazaki’s films is that there is no clear good vs evil dichotomy. They are very un-american in this regard. Where Disney or Hollywood always provides a clear cut villain, and there is a struggle by a hero to triumph over evil. In Miyazaki’s films often these concepts interpenetrate each other; phenomena exists; its not necessarily good or bad and the main hero seeks harmony not triumph.

Years ago, I wrote on Spirited Away for an Asian Cinema class in college. I lost the file since then but hopefully what I remember can contribute to this comment thread.

Like most of Miyazaki’s movies, Spirited Away is packed with symbolism and cultural commentary of modern Japan which a foreign viewer might not notice at first glance. I’ll focus on just one cultural phenomenon the movie comments on heavily – salaryman culture and capitalism.

The Japanese salaryman is characterized by lifetime employment and unending devotion to the company he’s employed by. This is the figure you see in movies who leaves to work before his family wakes up and comes home to a sleeping family and a wrapped plate of food on an empty dinner table. This work ethic and attitude was the cultural norm for working Japanese men from the 1950s, where salarymen were considered the engine of Japan’s economic recovery. It later became a topic of critique in the 1990s and 2000s after the Japanese economy collapsed.

What does this have to do with a movie about a lost girl and a spirit bathhouse? Everything, really.

Although the bathhouse is physically a symbol of traditional Japan, with its architecture and spirit clientele, at its heart is capitalism and salarymen. The bathhouse proprietress and witch Yubaba is a symbol of cold, indifferent capitalism. All her actions are motivated by money and gain. There is a scene when her baby is transformed into a hamster. When Haku tells her something precious of hers is missing, Yubaba first looks at her gold and treasures before looking for her child.

What of the bathhouse servants? They are all indentured servants to Yubaba, who takes their real name from them (which in turn suggests what capitalism is distorting and erasing Japanese identity). This is similar to the norm of lifetime employment, where a worker’s individuality is replaced by the wills of the firm. Even those who have the opportunity to leave are reluctant. Chihiro’s friend Rin mentions she has always wanted to take the train away from the bathhouse, but never does. Kamajii, the boilerman, has held train tickets for 40 years. But he never left.

The workers are all also motivated by money. When No Face visits the bathhouse, the workers fall over themselves trying to please him for gold. They humiliate themselves for wealth, which of course turns out to be an illusion after No Face leaves.

On a side note, pay attention to Yubaba’s quarters. It is one of two locales in the movie with overwhelming European design, the other being her twin’s cottage. In this way, Miyazaki balances his commentary on western influence on Japan. Although it contributed to the heavily capitalist society of modern Japan, also introduced were elements of warmth, family, and care.

There’s a lot more there, including the symbolism of water, the train, the everchanging sea level, and Chihiro’s odyssey-like journey. Miyazaki’s ability to infuse these thoughts into a family movie is part of what I feel makes Spirited Away special.

Also keep in mind at the beginning Chihiro’s parents, with their foreign-made Audi full of brand name products and purchases, driving blindly through the woods without giving a damn. They literally remark that the ‘abandoned’ amusement park they find must be a relic from the 90s boom, and when they start eating all of the food they can find, they wave off Chihiro’s concern by saying they’ll be able to pay for it on credit. Then they turn into literal pigs.

Your comment and view are just beautiful. Thanks for sharing this with us.

The capitalism view of the bathhouse fits a lot better than the prostitution view does.

Yeah this is a great insight, thanks a lot for this. On the point of the everchanging sea level, there’s of course a characteristic Miyazaki exploration of our relationship with nature and the environment. In a truly astonishing sequence, the river spirit that comes into the bath house is revealed to be filled with rubbish and discarded items. And Haku turns out to be a river spirit, whose river has been “filled in, it’s all apartments now”, which is why he can’t find his way home.

What a thoughtful article! This is truly fascinating. My oldest kid loved this movie as a kid, so when we had a movie night last month, we watched Spirited Away. She was really blown away by the social commentary that she missed as a little girl, and she loved how you can get different things out of the film when you watch it at different stations in life.

I’m a huge fan of Studio Ghibli. However, the first film I saw of his was Spirited Away because it had gotten so much praise. I remember watching it and liking it, but also feeling like the story just kind of ended. I didn’t really love it.

So years later, having seen all of their films like a bazilllion times, I realized how much I fell in love with Spirited Away. It was a film that after many rewatches, I just came to fall in love with it more and more. I think the thing that really made it click with me, is that it’s a story about having to get used to changes. It obviously takes this on from the perspective of a young child that is forced to deal with a move to a new city. But even adults can relate to the feeling of having to take on a new job, a new environment or also having to start over again. Even as an adult it’s scary.

I think what Miyazaki films do so well, is they capture the emotion behind things we have to tackle in life.

Great thoughts on Spirited Away. Many of the creatures and characters seen can be linked to old films and plays which, if you’re a Chinese/Japanese/Korean person who grew up with such stories, enable them to relate and immersify themselves in the story more. And to a western audience, you get that really foreign oriental and mysterious feel to it all.

I liked the article, which goes deeper into the nuances of the film. I thought Spirited Away to have moral lessons throughout. That was one of the reasons I enjoyed the film. The moral lessons were given in a non-dogmatic way; the film didn’t patronise the audience, and often inspired thinking beyond the black and white confines of right and wrong.

Spirited away is a story about many things but the main one is chihiros growth.

The subtext of it is fabulous in this animation.

This is it is my favorite animation. For example, the parents are thoroughly Westernized, gluttonous, mired in excess. The ghosts are all actual Japanese folk spirits which would be well known to audiences there. There is a pervading sense of a dark layer behind reality in the film, like a Murakami novel, a lingering effect of the Westernization of Japan and the perceived loss of Japanese-ness.

As an American who saw this in the theater for many years ago, I can only say that no movie has ever taken me away to another world like Spirited Away. I forgot all about the outside world.

I personally have always interpreted No-Face as a literally faceless, blank but impressionable mold who is entirely developed by his experiences. He turns into a monster because he is corrupted by the bathhouse and its materialism.

This is what I think too, hence Chihiro’s line when they leave the bathhouse, “I think being in the bathhouse makes him crazy.”

Yup, and then when he’s in Eubabas sisters house he’s very friendly and fine because of the ideals at play there of family.

I’m confused by this because they warn each other not to let him in or get anywhere near no face, like twice. As if they know what he is it what he’s going to do. But then when he gets in the bath house they forget who he is or something.

Spirited Away as an anti-work piece.

Very fascinating article, thank you for writing it.

I don’t think we can look at spirited away as an analogous story where every character represents some idea/event/individual. That’s my mantra on the film, what follows may seem paradoxical as I kind of draw an analogy… But hey whatever.

The two major philosophies influencing Japanese culture traditionally, particularly within the arts, are Shintoism and Zen Buddhism. Shinto, the way of the spirits, is clearly evident. Zen Buddhism, I believe, is relevant as well within the world of Spirited away but not as noticeably. In zen you’ve got these things called Koans, meaning a case, similar to a law case I suppose. A koan is meant to be almost like a riddle, that seems to have an answer and so you toy with it intellectually, from every angle trying to discover the hidden meaning which will lead you to enlightenment. Most famously, perhaps in the west, are koans such as: what is the sound of one hand clapping? Or, if a tree falls in the woods and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound? They seem to have answers, you think you can solve it, but the idea isn’t to arrive at a sensible, reasonable neatly packaged answer, but rather to enquire and question as a method of examining the mind in the throes of trying to map meaning on the turbulent churning void of existence. I think that’s the role of No Face. I think he is, at first viewing, almost glaringly representative of… of… Something.. Greed? Corruption? I think he is a character that fools you into thinking there is a parallel between our world and the spirit world and that everything would make so much me sense if you could understand what he stood for. He doesn’t stand for anything. He is a spirit, in world of spirits. That should be enough.

Suzuki said that no-face was a representation of a part of Miyazaki. No-face desperately wants to enter the hearts of people but lacks the tools to do so. Miyazaki probably feels this way. That is partly why he may have chosen the career that he did. Miyazaki’s first animated movie brought him to tears because he thought it was so beautiful and he wants to do the same and touch other people in the same way. Fun fact: there is a scene in “the white serpent” (what inspired him to go into animation) that shows the serpent flying or moving in a similar motion that you see in Spirited Away when Haku is being chased by the Shikigami.

I think Miyazaki used No Face to represent Greed and Corruption of human society. That’s why it keep following Chihiro. Because children are born innocent and then the worlds greed tries to corrupt them. In the movie, Chihiro keeps fighting it off and chose to do the right thing, take care the environment/Haku/Dragon/River. I think the film is Miyazaki want to show little girls that they can be more than just romance crazed princesses. They can have morals, sense of right and wrong, fight for it, and make a difference. Just my 2¢~~

Those last two sentences can be said about nearly every Miyazaki film…Spirited Away goes well beyond just Chihiro in terms of theme and symbolism

Explain to me who or what No Face is please.

Capitalism, abundance as sin maybe?

More specifically he’s the white man that came to japan last century. He spends his gold everybody bending backwards for it but actually devours everything. His mask is friendly and smilie but there is a ravenous dark mouth underneath. He has no real face (face is a concept of reputation and honor in japanese society). But truly he is lost and good underneath. Just his capitalist hunger makes him frightening. In the end he falls in love with Japan and the customs.

I saw him like a mirror of Chihiro and her behaviors along the story.

He seem childish, greedy, he get angry when he don’t have what he want. Chihiro might have recognized that all of this was pointless and showed him what she has learned to “grow up”.

Otherwise I have no clues about japanese culture and such. Its my canadian point of view

I don’t know if this is even a thing in Japan, but it might have something to do the idea with “having face”, that is present in some Asian countries. That is where the expression “saving face” and “losing face” comes from, although in certain other countries like China (and I am pretty sure Japan too) it is a very complex concept.. but it is basically about pride and dignity.

No Face might have lost his face, and is someone completely devoid of dignity or social capital. Because of his lack of dignity he might also have no reason to not indulge in gluttony, because he has no sense of shame.

I have always felt he reflects the hearts and minds of those around him. That is why Yubaba didn’t want him inside the bath house. Not because he was a bad spirit, but because she knew the greedy, selfish spirits would turn him into something dark. I feel like if Chihiro had taken his gold with good intentions he would not have harmed her.

Kaonashi represents the desire for respect and companionship, and the kind of melancholy that comes from that. Initially he stands in the rain, watching others having a good time, wanting to be a part of it. As some other redditors astutely pointed out he seems to go crazy at the bathhouse, trying to buy friends and respect with gold. But that doesn’t work (you can’t buy friends) and he still feels as empty as ever, and seeks out Chihiro for true companionship.

in the original Japanese, when Chihiro rejects him during his binge, he shrinks and mutters “sabishii,” or “lonely. I think this is his critical line. Even though he’s grown fat and seemingly has everything he lacks the respect and friendship of Chihiro. And because he’s surrounded by sycophants and golddiggers, in his pain of rejection he becomes paranoid and suspicious (“you were laughing weren’t you?”) and starts on a rampage.

Finally at Zeniba’s place they seem to respect him for who he is and tells him he needs to work for his keep. He eagerly accepts this, as he realizes this is where he will find the companionship he needs, provided it’s in balance and he works for it.

Someone else pointed out that there is an expression of “having face” or “saving face.” I think this is related – someone with no face has no respect, no demeanor and does not have friends or respect. So Kaonashi initially starts off by consuming the frog and adopting his mannerisms – just as someone who doesn’t know how to make friends or socialize will start doing so by imitating someone else.

Anyway those are my thoughts.

Lovely post. I will watch this film and come back here to read it again.

Spirited Away is not just an animated movie, it is art, philosophy, lifestyle, culture, beauty, magic, dream, happiness, a reason to breathe, a lesson to be learned, a purpose of life, an escape of reality, a motivation to keep on living.

Just finished it. And oh my god. Its beautiful. Best animated movie by far…

Just because a lot of people tend to be confused about No Face, here are some thoughts: I think as kids we were all kind of scared of no face but if you take off his creepy image you’re just left with a child.

I think No Face was supposed to represent the way children, or young minds are influenced by the adults and environemt around them and if not taught right or wrong, will do anything to aquire their parent’s love (which was kind of Chihiro’s position in the film). So in the bath house, the people were greedy and so No Face reflected their greed. I think the way he aquired the frog’s voice after swallowing him was also very reminiscent of the way children often swallow the words of adults and copy them. So, it’s not like he ever wanted to be served mountains of food or be treated like a royal, he just wanted people to pay attention to him and blindly, he thought that he could buy people’s affection with money, but he couldn’t.

The one person who showed unconditional kindness to him (Chihiro) wasn’t interested in his gold and he didn’t understand why and thus the whole rampage. By deliberately making him a creepy character, I think that Miyazaki was covering what was at the core of his actions. However none of this was said by Miyazaki nor the film which is exactly what makes Miyazaki’s films so great. The characters, the story is just placed there and no opinions about them are stated, not even by the protagonists (who are often neutral) just left there for the audience to question and interpret.

I believe no face, once he entered the story just adored Chihiro. She was the first person who was nice, and treated no face like a regular person. He then noticed how the others all wanted money/gold and in turn tried to give that to Chihiro to show his appreciation but she was focused on other things. Once he realized she had no want of the gold and hold more important things in mind(her parents), he got confused/upset and overreacted because he didn’t know how he could get her attention. In the end she understood how he felt and ultimately forgave him. This to me is basically the modern day friend zone realization lol obviously this is just my interpretation.

Awesome article

Excellent look at Japanese culture! I particularly like your discussion of mis-naming, mis-speaking, and name theft. It might have given me an idea for a piece.

Since I was a child, the very idea of No-Face caught my attention. A spirit capable of swallowing other people’s emotions and changing his behaviour as a consequence is certainly an interesting topic to discuss. I believe that this character is the representation of the concept itself of reaction, reaction to all the things we are constantly forced to face: every day, we always get the chance to learn something new, to make up our mind and change it according to new evidence, and so on. No-Face reminds us that our “bad choices” eventually lead to serious problems, though it is often still possible to redeem ourselves.

It is so interesting to place chaos as the central feature in the Bathhouse of the Demons. Children definitely identify with the main character, perhaps because all parents disappoint at some point, and perhaps because children are taught at an early age about structure and routine, and the safeguarding within that. The commentary on vulnerable children finding chaotic environments as a last refuge speaks to our modern epidemic of youth runaway and homelessness. Running out into the chaos may feel like an escape, yet runs such a high risk for adult manipulations (sadly, our modern day gold coins of being fed, housed, befriended). Given that most countries signed the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, it would be great if children didn’t feel like they were basically on their own to figure things out at such young ages.

Since childhood, Spirited Away has been one of my favorite animated films. The imaginative plot captivated and inspired me to always look deeper into everyday events and find the truth deeply rooted in all things animated and unanimated. This animé generates in me the need to explore this vast world and be ok with ending up somewhere that I didn’t necessarily intend to be. I’ve always known that Spirited Away was a prime example of how, regardless of our plans, life can catapult us to faraway places that we never expected to be.

This is very well written. I’ve seen this movie several times as I’m a big fan of amine and never really thought of the movie in this context. Thank you!

All Studio Ghibli movies have such a strong message about nature and industrialization.

I feel like all of Miyazaki’s films have some commentary on society, but through the eyes of a kid, since kids are usually the protagonists of his stories. I think they also point out just how much kids see and understand as a third party as oppose to adults who more or less become part of the system. Seeing this interpretation of such a beloved kid’s film was really interesting, because when you take Chihiro being the main character into account, and the fact that the story, while scary, does contain some element of whimsy, really highlights Miyazaki’s appreciation for a child’s viewpoint of the world.

This movie doesn’t show it at first but upon deeper review, it shows the dark and disturbing reality of social classes and issues that are often swept under the rug for lower class people. It shows the greed and exploitation of workers as well as the classic power higher officials had.

Very interesting analysis

Very interesting, I hadn’t considered the bath house as being as heirarchical as you’ve demonstrated. It also caused me to consider that it may be possible that the spirit world in Spirited Away is focal upon the subconscious of society, emphasising imperceivable notions and concepts to appear almost tangible. In this way, its very interesting to observe the parallels between the human world and the spirit world at a societal level.

You have opened my eyes to something i had never really thought about whilst watching this beautiful film. I’m kinda sad now 🙁 But also loving how much more depth is discovered after analysing it further. It is an eternal classic. You’re epic.

So great to read this article— one of my favorite movies and I’ve always thought it reads totally differently when you view it through a lens of capitalistic greed. Sen was different in that she didn’t buy into all of it, which led to her exaltation from the system

I’ve loved spirited away since I watched it first when I was a kid. I had no idea about some of the contexts behind the story. Loved the article!

Spirited away is one of my favorite films and I find it so interesting to see how other people interpret the nuances of this film.

strong message !!

It’s amazing how different perpsectives and elements become visible every time you watch a good piece of film. That’s the secret to powerful and effective art – being able to present a lot of underlying arguments at once. A reminder I need to re-watch the movie again!

Spirited Away did deserve an Oscar, and it is a piece of art that represents Studio Ghibli’s tackling with relevant social issues. Surely a masterpiece!

You put a lot of thought and detial into this article and you meaning of things. It was really intresting to read and it made me think a lot, even thought I’ve never watched the movie before.

To the point of yubaba stealing names and creating servants from them. In a lot of media, cultures, etc. We see that a name is somehow bound to a person’s soul, a simple name being that person’s entire identity. Once you control that, what can be done?

Furthermore, the bathhouse in the movie is basically like a little model of the whole world economy, where the rich bosses take advantage of the workers. But it’s not just about that – the movie also talks about how we shouldn’t forget the old ways and traditions, or else bad stuff can happen. Spirited Away really makes you think about how our actions impact society and the environment. Awesome masterpice!

I think the bit with Haku’s lake being cemented over is absolutely a criticism to how humans treat the climate and the earth, since we know how hayao miyazaki is.

I think this article does a good job of telling how Spirited Away is a Japanese movie full of imagination.