The Quay Brothers’ Universum: Sculpting a Psychic Topography

Despite their American roots, the work of the identical twins the Brothers Quay exhibits a distinctly European sensibility. Coming to relative prominence in the 1980s when their short film Street of Crocodiles (1986) achieved critical acclaim, winning ‘three prizes at the 1986 Zagreb Animation Festival and the Grand Prix at Odense, Sitges, Brussels and San Francisco’, (Kitson, 82) the Quays have nevertheless avoided becoming a household name. Eschewing the easy accessibility that the inherently British humour of Aardman’s Nick Park and what Mark Salisbury terms the ‘identifiable brand’ of Tim Burton lend to these animator’s works, the Brothers instead opt to share a liminal status with the objects which they use in their films. Where Burton and Park, though varying hugely in visual style, both make films largely for children, the Quays believe that model animation is a style which is unfairly sanitised by the preconception that it appeals only to a younger audience. In an interview conducted in Paris’ Doll Museum by critic Yves Montmayeur, they expressed uneasiness in the ‘constrained’ and ‘codified’ children’s dolls, ‘caught in the last breath of Victoriana’.

By their very nature as imitations of the human form, puppets have long been considered avatars, or loci for the projection of the human situation; as Paul Wells writes, ‘the puppet and the marionette tradition in Czechoslovakia was important in sustaining the Czech cultural and aesthetic identity in the face of other influences, particularly that of the German language’ (Wells, 186). The effigies of human life were not just tools for entertainment purposes, but loaded symbols of a nation, charged with maintaining a cultural system in the face of an interrupting force. Steve Weiner expands on the importance of the Czechoslovakian puppet theatre as a way of keeping tradition alive:

Itinerant puppeteers had for centuries carried debased versions of theatre into the countryside and poor parts of cities. They unwittingly preserved the oral, archaic powers of expression. Plays were reduced to essentials and sometimes ended without dramatic resolution. Puppets, especially those representing the poor, were grotesque. Appearing as types, not personalities, their feet filled with lead, they moved stiffly without resistance. Their style of movement could be, at times, metaphysical metaphors.

(Weiner, 29)

The puppet figures, already abstracted from the human form in their scale, become further removed from reality in their archetypal caricaturing, and can thus be thought of as semiotic referents of humanity, much like an earlier form of ritualistic effigy, the mask. M. Subbiah writes that ‘masks may disguise a penitent or preside over important ceremonies; they may help mediate with spirits, or offer a protective role to the society who utilise their powers’, and ‘in some cultures it is also believed that the wearing of a mask will allow the wearer to take on the characteristic of that mask’s representation’ (Subbiah, 22). The effigy then, be it mask, puppet, or otherwise, holds power; where the mask is a symbol of a spirit or god, a means of channelling a divine or Other power, the puppet works in an inverse fashion, as an avatar of the human mind or spirit.

In her study of The Secret Life of Puppets (2001), Victoria Nelson posits that ‘we can locate our unacknowledged belief in the immortal soul by looking at the ways that human simulacra – puppets, cyborgs and robots – carry on their role as direct descendents [sic] of the graven image in contemporary science fiction stories and films’ (Nelson, viii). While such comparisons have been made and expounded in reference to the Other and Orientalism by such scholars as Joon Yang Kim, it is of greater interest to this argument to note Nelson’s comparison between the puppet and the ‘graven image’. The significance the term holds is twofold; Nelson employs it to denote a spiritual quality in the simulacra she discusses, but etymologically, the word ‘graven’ leads back to the old English ‘grafan’, ‘to dig’, and so naturally also the more recent form, ‘grave’. ‘Grave’, of course, leads to ‘engrave’, and so a comparison between the graven image, as an image which is carved, and sculpture may be made.

The puppet, then, may be considered a moving graven image, both in the sense that it has been shaped and crafted and that some spiritual or metaphysical significance may be attached to it. The puppet being thus consecrated as both an expression of the immortal soul and an avatar of the human psyche, it is no surprise that both Nelson and Buchan make reference to Joseph Campbell’s monomyth structure in their respective studies of puppets and the Brothers Quay. The puppet effigy acts as an avatar, a veritable Theseus exploring the labyrinthine depths of the collective unconscious, the hero entering Campbell’s ‘Belly of the Whale’.

The Quay’s films, as they themselves point out, ‘are fixed systems in which an intruder arrives, and the intruder either upsets the universe, or unbalances it’, and so whilst change is introduced, a resolution is generally reached. The Czech films have political overtones, while the Quays’ evidence a greater concern for the psychological, drawing as they do on the likes of Bruno Schulz and Franz Kafka, and it is for this reason that this article applies the term ‘liminal’ to their work; the influences upon which they draw and the worlds which they create occupy a space within the topography of the subconscious, and their puppets are our guides, couched upon the threshold.

‘We build everything from the ground up’, the Brothers explain, often starting with the puppet and working outwards. The puppets themselves are generally assembled from trinkets and scraps of found material, woods, metals, and fabrics, all chosen for their tactility and scars of time. A ‘combination of found objects creates the puppet’, they elaborate, and the puppet often gives them a sense of how their film will take shape. Their beautiful, sculptural sets grow thus grow around the armature, indeed grow from the armature, externalising the emotional and mental state which the Quays perceive in it.

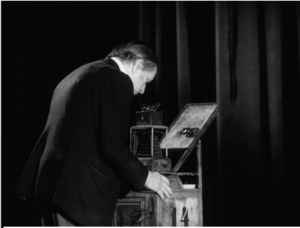

Of all the films in the Quays oeuvre, Street of Crocodiles is perhaps the one which best illustrates this idea. The opening sequence sees a man approach a kinetoscope, behind the viewing reticule of which is what the Brothers describe as ‘a map which demarcates a very specific, vague area of a map of the town which comes up only as white, i.e. that it’s a zone that can’t be marked off and is sort of mysterious and unknown’. As the man looks into the device, the film moves from monochrome to colour, a trope which, in the wake of the likes of Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946), is broadly understood to signal a transition between the realities of the waking and dreaming worlds. ‘The price of admission’, the Quays inform us, ‘is one drop of saliva’, and this offering of bodily fluid sets the mechanisms of the device in motion; the ritualistic sacrifice of a fragment of the self brings life to the motionless and grants access to the labyrinthine underworld occupied by the film’s puppets.

The Quays readily acknowledge this godlike bequeathal of life through ‘the wooden esophagus’, the title once again calling to mind Campbell’s mythic ‘crossing of the first threshold’ and subsequent journey into ‘the belly of the whale’, the esophagus acting as a bridge between worlds. As Nelson writes, ‘Freud psychologized and secularized the transcendental by advancing the notion of homocentric subjectivity – that we project inner psychic content onto the world around us in structurally the same way that God was formerly supposed to have projected his reality onto us’ (Nelson, 16-17). The spit acts as a transference of consciousness, a manner of activating the golemic puppet which is subsequently freed of its earthly ties as the scissors sever the thread which binds it.

Thus anchorless, the puppet is free to roam the grotto that is the titular Street of Crocodiles, the mysterious and unknown region of the map hitherto unexplored. Intentionally or not, the Quays have crafted a topography born of their own experiences. At their retrospective at MoMA in 2012, the Brothers explained that they wanted people to experience the exhibition as a maze because it mirrored their own experiences as they ventured into the world of film production. Their dark and eerie exhibitions thus become brooding grottos, immersive sculptures which recall Peter Selz’s description of environmental sculpture, in which the viewer ‘finds himself surrounded by the sculpture he is allowed to enter’ (Selz, 10). The viewer thus becomes participant, adopting the role of the puppet within the film and exploring the psychic topography of the Quays’ Universum. The puppet, as an avatar of the viewer, is a locus for the projection of the self, a mask which helps us to mediate with the spirit of Schulz as it is channelled through the world created by the Quays.

Photo: Ed Jansen

The Quay Brothers’ Universum, an exhibition held at The EYE Film Institute in Amsterdam between December 2013 and March 2014, was a veritable wunderkammer, showcasing the various sets, puppets, props and influences which the Quays have collected over the course of their filmic career. The exhibition occupied a darkened gallery, display cases and projected films looming out of the gloom to reveal the various macabre trophies which have found their way into the Brothers’ films; an array of Polish film posters, archaic medical paraphernalia, books, films and the Quays own illustrations, entering the gallery space was like walking into the mindscape of the Brothers themselves.

Just as the the Quays’ films grow out of the influences which were displayed in their Universum and can thus be seen as both the externalised product of the Brothers’ creative process and codified amalgams of said influences, the exhibition can be seen as a physical representation of their psychic topography, an environmental sculpture which allows an audience to step into their collective mind. Where the wunderkammers of old were a way for the wealthy to accumulate trinkets and trophies which signified a dominion over the larger world from which they were sourced, the Quay Brothers’ exhibitions signify the framework through which they view the world around them.

Where they were disappointed with the inability of their work in illustration to convey a sense of narrative through the extra dimensions of movement and music, the Quays found in the animated film the capacity to portray invisible forces through the manipulation of light and kinesis, the temporal medium allowing them to suggest the presence of the invisible through its very lack of visibility and their sculptural puppets giving physicality and life to history, emotion and mental turbulence.

Indeed, the Brothers, as Suzanne Buchan explains, are more concerned with the stories told by the objects they utilise in their films than in composing their own dramaturgical narratives:

The Quays films pay attention to isolated objects, sometimes more so than to the relationships between puppets; figures are often at a loss to deal with the inner life of these objects as they move in intricate patterns in the spaces and soundscapes that surround them. These assemblages and material configurations are animated through the expressive realms of human thought, dream, and experience – in this case, from the world of literature.

(Buchan, 44)

She writes of the ‘intricate patterns’ and ‘expressive realms of human thought, dream, and experience’, highlighting the fact that their puppets and armatures make no attempt to foreground the narratives of the texts upon which their films draw, moving instead in response to the turbulence of the psyches behind the words which the filmmakers have read. As such, the Quays’ puppets can be said to be akin to ceremonial masks which allow for the channelling of the authors behind the works which the Brothers favour.

Where the puppet protagonist of Street of Crocodiles is an avatar through which the man in the museum traverses the wooden esophagus to explore the titular street, the Quays’ exhibitions reverse this doubling process to bring the Belly of the Whale into the real world. Their films may act as windows into both their own minds and those of the artists whose works they draw on, but the Brothers’ gallery shows act as a means of inviting us to step bodily in their minds, to surround ourselves in the sculpture which we are allowed to enter.

Works Cited

Buchan, Suzanne, The Quay Brothers: Into a Metaphysical Playroom (London: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

Campbell, Joseph, The Hero With a Thousand Faces (Novato: New World Library, 2008).

Kim, Joon Yang , ‘The east asian post-human Prometheus: animated mechanical “others”’, in Pervasive Animation, ed. by Suzanne Buchan (London: Routledge, 2013), pp.172-194.

Kitson, Clare, British Animation: The Channel 4 Factor (London: Parliament Hill Publishing, 2008).

Nelson, Victoria, The Secret Life of Puppets (London: Harvard University Press, 2001).

Salisbury, Mark, Burton on Burton (London: Faber and Faber, 2006).

Selz, Peter, Directions in Kinetic Sculpture (Berkeley: University of California Printing Department, 1966).

Subbiah, M., ‘Masks: History, characteristics and functions – Global Perspective’, in Indian Journal of Arts, 1:2, 2013, pp.22-28, < http://www.discovery.org.in/PDF_Files/IJA_20130201.pdf> [Accessed 22nd March 2014].

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Throughout the whole movie Bane seems like someone that you could fear. Like he would beat The hell outta you. But when I saw him crying because Rals al Gaul daughter told batman that her father could not accept him. It just changed the whole perspective of the villain.

I saw their exhibit at the MoMA, but I only saw the “maze” part which was what I cared the most about seeing, although it would have been awesome to see these guys speak.

In my opinion, Street of Crocodiles is about society leaving the many things in our life unfinished.

The director Brothers Quay came to our school last month!!!

Was looking forward to seeing their interpretation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis

My favorite short animated film (Street of Crocodiles, 1986). I love stop-motion, and I also think it inspired a LOT of ’90s videos. (I’m looking at you Tool and NiN)….

The first time I saw this was at a film festival downtown, & I was completely blown away. They showcased several films by the Quay Brothers, “Street of Crocodiles” being the first one. The dark & twisted romance of the whole story, the music, the art, the sets, the sound effects, & the characters most of all, really hold a special place in my memory now.

Basically butoh and steam punk (before steam punk knew what it was).

I love their work. Amazing. Anamorphosis is a favorite. I didn’t see the exhibit.

Bloody amazing work.

Really interesting subject, puppets are — I enjoyed reading this piece. Though I rarely think about puppetry, I do feel its allure and can think of multiple instances in which the concept of puppetry left its impact on my mind. Maybe the most striking comes from Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s film The Puppetmaster. In talking about the marionette tradition in Czechoslovakia you write that the “effigies of human life were not just tools for entertainment purposes, but loaded symbols of a nation, charged with maintaining a cultural system in the face of an interrupting force” — The Puppetmaster expresses a similar idea, only in reference to Taiwan. If you’re into how puppets and the like become metaphysical metaphors, I recommend the film (just in case you haven’t already seen it).

Street of Crocodiles is a powerful short film.

This is very well written. Very scholarly. I appreciate how focused your writing is.

Dear Ewan,

What a deeply touching article you wrote …………. actually more than touching but profoundly measured and considered. Strange as Joon Yang was just here in our studio last week staying with Suzanne Buchan who was away at a conference in Canada. Anyway it would be very nice to run into you one day in some distant Enoteca probably left of right ,,,,,,,,,,,,,,, to be continued there if we can buy you the first drink ……………… Very best wishes

QQs

Dear QQs,

I can’t say that I’d expected you ever to see this article; I sincerely hope that these kind comments aren’t just someone pulling my leg. I’m likewise unsure if you’ll see this reply, but the article is drawn from my undergraduate dissertation on the works of both yourselves and Jan Svankmajer, a copy of which I would love to provide for you should you wish to read it. Should we cross paths in said Enoteca, the wine is on me.

Kindest regards,

Ewan

The aforementioned dissertation, for anyone interested:

https://www.academia.edu/7481472/E_Wilson_-_Diagrams_of_Motion_Stop-Motion_as_a_Form_of_Kinetic_Sculpture_in_the_Short_Films_of_Jan_Svankmajer_and_the_Brothers_Quay

Dear Ewan,

The determined Enoteca wouild have to be officially off this page somewhere not in the full glow of artifice. Is that a possibility also left of right ???

Sincerely

QQs

Dear QQs,

Of course. I can be reached at [email protected] if e-mail contact is amenable?

Regards,

Ewan

No way… Ewan, was it real? It seemed real.

I’m a big fan of Street of Crocodiles, but my personal Quay fave will always be Anamorphosis. It’s not only an inimitable weird animation, it’s also a history of western art and a great introduction to the science of optics!

The Czechs do like their puppets and clay animation indeed, as someone that saw a number of these sketches when I was younger. See Pat i Mat.