Books to Discover French Literature

French author Victor Hugo once wrote: « Lire c’est voyager, voyager c’est lire ». It means « reading is traveling, traveling is reading. » So let’s take a trip to France and explore French literature through twelve french literary works, all the way from 1666 to 2010, including novels, poetry, essays, short stories, comic book, and plays! The list will be chronological, and, while the primary goal is to show a broad and representative panel of works and authors, an emphasis will also be put on less-known pieces!

Molière, The Misanthrope, or the Cantankerous Lover (1666) (Le Misanthrope )

The Misanthrope is a comedy written in verse by Molière, a very famous French playwright from the 17th Century. Molière is famous for his comedies (The Bourgeois Gentleman, The Impostures of Scapin, Tartuffe or the Impostor, Don Juan or The Stone Banquet…). Therefore, The Misanthrope is often categorized as such. However, things might be a little bit more complex than that. By many aspects, The Misanthrope, is, indeed, a comedy, but there is also inherent darkness to the story. The main protagonist, the so-called “misanthrope” from the title, is named Alceste. As he says himself, he hates human nature and mankind. He despises the hypocrisy and the cowardice that govern the court and the aristocracy, and he is quick to point out everybody’s flaws, including his own.

Indeed, for five acts, Alceste is put in the middle of a love triangle. He is madly in love with Célimène, though he knows he shouldn’t be, as the socially-minded and flirtatious lady is everything he hates. Meanwhile, two other women – the prude and moralist Arsinoé, who, deep down, is jealous of Célimène’s beauty and appeal, and the quiet and honest Eliante, who is married to Alceste’s friend – both pine for Alceste. Under those sentimental intrigues that unveil Alceste’s mind and the societies’ flaws, the protagonist is also entangled in a trial after he offended an acquaintance by speaking his mind regarding the poem the other man composed.

Alceste’s excesses are funny and laughable, yet they also lead to question our own point of view on society, as well as our behavior within it. Characters are nuanced and they evolve throughout the play, though Alceste’s final decision was prophesied from the very beginning – a trait often found in tragedies. All along the play, Alceste stays an ambiguous character, a feature that some authors were prone to criticize. For instance, Jean-Jacques Rousseau deeply regretted the way Alceste was ridiculed on stage, as the character shared Rousseau’s own view of the world. Whether Alceste is a heroic and misunderstood character because of his deep honesty and integrity, no matter how harsh those maybe, or a neurotic and laughable fool, will depends on the reader or viewer’s own sensibility. Yet, some French teachers have noticed a slight evolution in some readers’ perceptions. A few decades ago, students seem to be more inclined to laugh at Alceste than they are today, taking now pity of the man and seeing some truth in his sayings.

Jean Racine, Mithridate (1673)

Jean Racine is one most famous French playwrights and the emblem of French Classicism (1665-1725). Through his seven tragedies, he asserts his talents and takes a major part in establishing the rules of Classic French theater. His plays respect all the guidelines the French playwright of the 17th century had to follow: the “three unities” (unity of time, unity of place, unity of action), the mythological or classical inspirations, the goal of catharsis, five acts and written in Alexandrine verse. There was also the “rule of decorum” (“règle de bienséance”) which stated that no violent or bloody actions should ever happen on stage, so the audience would not be shocked. Racine generally respected that rule, except perhaps in Andromaque, where Oreste’s descend into madness could be considered violent. Racine is also known to add a profound depth to his characters, despite his plots being stripped down, purified. The other strength of Racine is his masterful use of the Alexandrine. In French poetry, as well as in versified plays, the poetic meter is the syllable. An Alexandrine line is, then, a line of twelve syllables, with a cesura half-line. The Alexandrine verse is, or at least was, considered, in French literacy and poetry, perfection. It is often very hard to translate in other languages, especially those which, like English, have usually different prosody.

Despite being among Racine’s Seven Tragedies, Mithridate is less-known and, today, less-staged than, Phaedra, Iphigenie, or Britannicus. Yet, at some point, it was one of King Louis XIV’s favorite plays, and also Mozart’s inspiration for his opera Mitridate, re di Ponto. Though it respects all the aforementioned rules of Classical theater, it is worth noting that Mithridate is the most epic play of Racine, as passionate monologues and long tirades are more numerous than in other plays. Mithridate’s strategy is Racine’s longest monologue. At the rumors of King Mithridate’s death, both of his sons – one, Xiphares faithful son aspiring to walk in his father’s steps, the other, Pharnaces the villain who allied himself with the Romans – come running to Monime, Mithridate’s young fiancee. Despite having opposite views and characters, and struggling to have the upper hand, both brothers are pursuing Monime. Plus, as Xiphares and Monime just declared their love to each other, we learn that Mithriade, Monime’s legitimate husband and Xiphares’ father, isn’t actually dead. Racine’s tragic love triangle intertwined with political affairs. The importance given to strategy and exterior wars, as well as interior conflicts, is also worth noticing. Indeed, the political aspect of the play is more highlighted than in any other play of Racine, and the playwright uses narrative patterns that may evoke some of Corneille’s works.

Voltaire, Micromegas (1752)

Voltaire is one of the few authors that may embody the entirety of the French Enlightenment movement, while his philosophical novella, Micromegas, is relevant both on the philosophical level and the literary one. Indeed, Micromegas encompasses and tackles many of the themes dear to the Enlightenment – social and religious critics, political revolution, science and knowledge, philosophic thoughts on mankind’s place and nature – while keeping the whole digestible, as its presents itself as a kind of fairy tale. To be more specific, it can be seen as a precursor for science fiction. Micromegas stages the discovery of Earth by two giants – Micromegas, who has been chased from his home-world because his scientific treaty has been ruled as a “heresy” and the Secretary of the Academy of Saturn he befriended and brought along in his travel through the universe. The giants, helped by their height that give them some distance – literally – roam the Earth and comment on their discoveries.

Through Micromegas’ gaze, the story chooses a relativist standpoint – relativism, as a philosophy, also being one of the ideas developed by the Enlightenment. Voltaire also draws and extrapolates from new knowledge of the time, laying, then, the basis to what would later be called “science-fiction”. We can also see Micromegas as Voltaire’s fictional alter-ego. Indeed, just like his character’s, some of Voltaire’s work was judged a “heresy” and censured, as the author – once again, just like Micromegas – was then forced to exile. Though Voltaire didn’t cross the universe during his exiles, he did cross the Channel, and, in England met, among others, Swift, whose universe may have inspired his.

Choderlos de Laclos, Dangerous Liaisons (1782) (Les Liaisons Dangereuses)

Written by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, Dangerous Liaison is an epistolary novel taking place in France, shortly before the Revolution, within the nobility circles and inspired by the soaring libertinism – which, at first, refers to a philosophy in which man’s law is not inferior to God’s law.

While the story tackles themes such as revenge and amorality, the novel revolves around the vicious game of manipulation and revenge between the Marquise de Merteuil and the Vicomte de Valmont, two rivals and former lovers. The letters written by these two lead characters drive the plot, while the letters from their victims – metaphorical human shield and deadly weapons to serve either Valmont’s or Merteuil’s ambitions – allowed an even more striking contrast. Knowingly and unashamedly, both the Vicomte and the Marquise use of their respective power, cloud, and appeal, to climb higher and higher on the social ladder, while deliberately trying to hurt the other.

These two main characters have very few redeeming features, and can easily be categorized as “evil”. Neither them nor the many people they hurt find their happy ending, and, despite being ambiguous, the ending of Dangerous Liaison doesn’t foreshadow anything good for any of our characters. Yet, and as the multiple adaptations of Les Liaisons Dangereuses show, something is fascinating about this story and its two main characters. As André Malraux points out in a famous text often used as a preface for Dangerous Liaisons, in 1782 there was no equivalent of Merteuil or Valmont. Such characters were, at the time, unheard of, completely new and fresh, revolutionaries. The story also explores its characters’ psychology with an unusual depth for the time. Though it is not enough to redeem her, there is something strangely moving, something that commands admiration, when, in Letter 81, Merteuil gloats about how she slowly became the woman she is now. How she got to extreme length to strengthen herself to keep her freedom, in this patriarchal world. How she played with lines and assumptions. How she literally “created herself”:

“Introduced into the world whilst yet a girl, I was devoted by my situation to silence and inaction; this time I made use of for reflection and observation. Looked upon as thoughtless and heedless, paying little attention to the discourses that were held out to me, I carefully laid up those that were meant to be concealed from me. This useful curiosity served me in the double capacity of instruction and dissimulation. Being often obliged to hide the objects of my attention from the eyes of those who surrounded me, I endeavored to guide my own at my will. I then learned to take up at pleasure that dissipated air which you [the Vicomte] have so often praised. Encouraged by those first successes, I endeavored to regulate in the same manner the different motions of my person. Did I feel any chagrin, I endeavored to put on an air of serenity, and even an affected cheerfulness; carried my zeal so far, that I used to put myself to voluntary pain; and tried my temper, by seeming to express a satisfaction; laboured with the same care and trouble to repress the sudden tumult of unexpected joy. It is thus that I gained that ascendancy over my countenance which has so often astonished you.”

The same story is recounted in the 1988’s movie directed by Stephen Frears. Though the words may slightly differ, the idea, the feeling, is the same, while the phrasing may be compared to discourses held by modern and famous characters, such as Cersei Lannister, from Game Of Throne:

“When I came out into society I was 15. I already knew then that the role I was condemned to, namely to keep quiet and do what I was told […] I practiced detachment. I learn how to look cheerful while under the table I stuck a fork onto the back of my hand. I became a virtuoso of deceit. […] [I]n the end it all came down to one wonderfully simple principle: win or die.”

The construction of the novel has been carefully thought by Choderlos de Laclos. Every detail, no matter how small, has its importance. Plus, the complex polyphony – there are no less than seven narrators – is accentuated by the duplicity of some of them and the internal focalizations. The reader has to be focused and involved in order to reconstruct the plot and proceed through the lies and the bias while forging slowly their own opinion on the various characters. Marcel Proust, in The Captive (La Prisonnière), wrote, about Dangerous Liaison, that it is “the most terribly perverse book” ever written.

Victor Hugo, The Last Day of a Condemned Man (1827) (Le dernier jour d’un condamné)

Far shorter and less abundant than Victor Hugo’s most famous works like Les Misérables or The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, The Last Day of a Condemned Man is just as engaged. More than a century before it was abolished in France, Hugo exposes in this short story his disgust for the death penalty.

As the title implies, the plot revolves around the last 24 hours of a condemned man. The protagonist has no name, and his crime is never specified (though there are a few hints that he may have killed someone). He is no one, a faceless and nameless man. He is anyone and everyone. Through the encounter with his daughter, readers can see how the outside world already forgot and discarded the prisoners.

Hugo wrote The Last Day of a Condemned Man as a kind of diary, where anguished thoughts are entangled with nostalgic tells from the past, from the man’s life before jail, before the death sentence. As readers, we share his daily life, we inhabit his cell and meet the prison priest and some other cellmates, we share his fears and thoughts, we share his vain hopes and tries.

The whole is enhanced by Hugo’s masterful writing. Many scenes are worth pointing out, but to pick only one, let’s go to the final chapter, where our man is drove to the guillotine. The crowd has gathered around the scaffold, jubilant. While not being as sharp as Voltaire’s, we can see here a bittersweet flash of irony to stress even more what Hugo depicts as a complete absurdity.

It was now my turn, and I mounted with a firm step.

“He goes well to it!” said a woman beside the gendarmes.

This atrocious commendation gave me courage. The Priest took his seat beside me.

They had placed me on the hindmost seat, my back towards the house. I shuddered at that last attention. There is a mixture of humanity in it.

I wished to look around me – gendarmes before and behind: then crowd! crowd! crowd! A sea of heads in the street. The officer gave the word, and the procession moved on, as if pushed forward by a yell from the populace.

“Hats off! hats off!” cried a thousand voices together, as if for the King. Then I laughed horribly also myself, and said to the Priest, “Their hats, my head!”

We passed a street which was full of public-houses, in which the windows were filled with spectators, seeming to enjoy their good places.

There were also people letting out tables, chairs, and carts; and these dealers in human life shouted out: “Who wishes for places?”

A strange rage seized me against these wretches, and I longed to shout out to them, “Do you wish for mine?”

Charles Baudelaire, Paris Spleen (1869posth) (Le Spleen de Paris)

Not as famous as Baudelaire’s verse poems The Flowers of Evil, Paris Spleen is a collection of poems written in prose. The device isn’t entirely new. As Baudelaire wrote in a letter to Arsène Houssaye often used as a preface, this work was inspired by Aloysius Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit. Yet, Baudelaire, with his renewed use of prose, among others, is the one who opened the road to modern literacy and modern poetry.

Baudelaire, the first French translator of Edgar Allan Poe, deepens here what he called “spleen”. The English word is used metaphorically and introduces not only a new word in the French language but also a new concept. Baudelairian “spleen” designates a crushing melancholy fuelled by a profound discontentment with life but also – mainly, according to some critics – by an acute zeal for living.

Often kept apart, Paris Spleen and Baudelaire’s main work The flowers of Evil, are not that different, on the contrary. While exploring the renewed freedom the absence of metrics gave him, Baudelaire kept searching and writing the beauty he found in the darkest, ugliest places. As he wrote, in the epilogue draft of The flowers of Evil: “From everything I’ve extracted the quintessence/You gave me your mud and I’ve turned it into gold”. The same process is at play here, as Baudelaire tries to seize ephemeral instants of beauty or strangeness in the gigantic city from which he draws his inspiration. Therefore, the poems can be read in any order. Each poem corresponds to a scene, a thought, an anecdote, a reverie, a portrait… that are not linked by any plot or narrative scheme. Baudelaire is particularly fascinated by the distinct feeling of loneliness within the multitude of the city.

Yet, in the teeming of the city, evasion is always possible. In The Flowers of Evil, such evasion was through dream, travel, and exoticism. We find remnants of it in Paris Spleen, but a new side of evasion is presented. It is particularly clear in the poem “Get Drunk”:

One should always be drunk. That’s all that matters; that’s our one imperative need. So as not to feel Time’s horrible burden that breaks your shoulders and bows you down, you must get drunk without ceasing.

But what with? With wine, with poetry, or with virtue, as you choose. But get drunk.

And if, at some time, on the steps of a palace, in the green grass of a ditch, in the bleak solitude of your room, you are waking up when drunkenness has already abated, ask the wind, the wave, a star, the clock, all that which flees, all that which groans, all that which rolls, all that which sings, all that which speaks, ask them what time it is; and the wind, the wave, the star, the bird, the clock will reply: ‘It is time to get drunk! So that you may not be the martyred slaves of Time, get drunk; get drunk, and never pause for rest! With wine, with poetry, or with virtue, as you choose!’

On a lighter note, it is Baudelaire, in Paris Spleen, and more especially in the poem The Generous Gambler (Le Joueur Généreux) who coined the sentence: “The finest trick of the devil is to persuade you that he does not exist.”, later paraphrased and popularized by the movie The Usual Suspects.

Proust, In Search Of Lost Time (1913 – 1927posth) (La Recherche du Temps Perdu)

In Search Of Lost Time is a monument of French modern literacy. The metaphor is even more fitting due to the fact the Proust build his saga of seven volumes like a “cathedral”. Ambitious and innovator, the story is a collection of the narrator’s memories, from childhood to adulthood. He is never actually named, Proust using periphrasis when needed, though one occurrence of the name “Marcel”, which is the author’s own name, seems to have slipped in the fifth volume, The Captive.

By many aspects, Proust wrote his memoirs with In Search of Lost Time, as many events and elements of the novel seem to have been directly drawn from his own life. Yet, the novel also tackles many deeply human themes and emotions with renewed accuracy and style. Art and its nature is a central topic in Search of Lost Time, as the book is filled with thoughts, reflections, and studies about art in general, and literacy in particular.

Very early in his life, the narrator is drawn to art and writing. He produces his first text in the first part of the first volume, Swann’s Way, Combray I (also titled Ouverture). The production of such a text is placed under the sign of urgency and necessity. The enjoyment he feels at the sight of the landscape in front of him has to be explored further, so the sight and feels wouldn’t linger in his mind with that bitter taste of missing something. The act of writing grants him even greater pleasure. Through personal experience, but also, as he grows up, through literary analysis, the narrator slowly becomes an artist, a writer.

This notion of art is intimately linked with another theme that Proust explores deeply: memory. The novel itself is presented as the childhood and adulthood memories of a grown-up narrator. Memories and remembrances sprinkle the novel while leaving plenty of room for “involuntary memory”. The most famous occurrence of this involuntary memory is the “episode of the madeleine”, in Swann’s Way.

“Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, except what lay in the theater and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, on my return home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump little cakes called “Petites madeleines,” which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted valve of a scallop shell. And soon, mechanically, dispirited after a dreary day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shiver ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. […] I had ceased now to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I sensed that it was connected with the taste of the tea and the cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savors, could not, indeed, be of the same nature. Where did it come from? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it? […] I can measure the resistance, I can hear the echo of great spaces traversed. Undoubtedly what is thus palpitating in the depths of my being must be the image, the visual memory which, being linked to that taste, is trying to follow it into my conscious mind. But its struggles are too far off, too confused and chaotic; […] I cannot distinguish its form, cannot invite it, as the one possible interpreter, to translate for me the evidence of its contemporary, its inseparable paramour, the taste, cannot ask it to inform me what special circumstance is in question, from what period in my past life.

Will it ultimately reach the clear surface of my consciousness, this memory, this old, dead moment which the magnetism of an identical moment has traveled so far to importune, to disturb, to raise up out of the very depths of my being? I cannot tell. Now I feel nothing; it has stopped, has perhaps sunk back into its darkness, from which who can say whether it will ever rise again? […] And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom, my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it. […] But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more immaterial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.

And as soon as I had recognized the taste of the piece of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-blossom which my aunt used to give me (although I did not yet know and must long postpone the discovery of why this memory made me so happy) immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like a stage set to attach itself to the little pavilion opening on to the garden which had been built out behind it for my parents (the isolated segment which until that moment had been all that I could see); and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square where I used to be sent before lunch, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine. […] so in that moment all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann’s park, and the waterlilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and its surroundings, taking shape and solidity, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea.

The other main theme tackled is, especially in the first volumes, the anxiety of separation. It is the feeling that opens the novel, as the young narrator fear bedtime, especially when his mother can’t kiss him goodnight. In the later volumes, many questions and thoughts about homosexuality make an appearance. The narrator’s sexuality is, at times, ambiguous, just like the author’s was. Indeed, many personalities claimed that Proust was homosexual himself, though he never actually came out.

Another aspect that makes the book so rich is its historical dimension, as it tells, though implicitly and through internal focalization, the evolution of French aristocracy from the 19th century to the 20th century, and tackles major historical events such as the First World War.

As the extract above may show, Proust’s writing is beautiful and detailed, though very complex, with very long sentences. It is in Search of Lost Time that one may find the longest sentence in French literature, in the volume Sodom and Gomorrah – 856-words long. Search Of Lost Time is also credited as the longest novel in the Guinness World Records.

Camus, The Stranger, 1942, (L’Étranger) .

The Stranger may be one of the most known works of the French author, philosopher, and journalist Albert Camus.

Its first sentence is the most famous opening sentence of French literature: “Aujourd’hui, Maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas.”, translated in English by: “Today, Maman died. Or yesterday maybe, I don’t know.”. It is followed by “I got a telegram from the home: “Mother deceased. Funeral tomorrow. Faithfully yours.” That doesn’t mean anything. Maybe it was yesterday.” That simple and emotionless beginning encompasses the main feature of Meursault, the protagonist: a detachment from the outside world. It is also that feature that will cause its demise. We follow that strange character, from his mother’s funeral to his own death, after being sentenced to it because he killed an Arab.

Throughout the book – which is severed in two parts, the killing marking the separation – Meursault is collected, cold almost, and always truthful, about what he thinks and what he feels – or don’t feel. Said like that, the story may seem very odd, absurd, or even revolting somehow. Yet, and despite The Stranger belonging to Camus’ cycle of the absurd, along with among others Sisyphus’ Myth, there is a deeper meaning to it. We could probably spend a whole article on that point, but here is what Camus wrote in one of his diaries:

I summarized The Stranger a long time ago, with a remark I admit was highly paradoxical: “In our society, any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.” I only meant that the hero of my book is condemned because he does not play the game.

Analyzing the “game” that is life, and how to “play” it a theme close to Camus’ heart, as he is also a famous philosopher.

Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince, (1943) (Le Petit Prince)

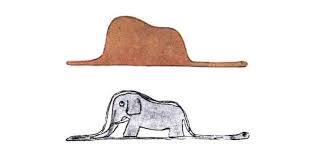

The short novel may be Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s most famous work. The story, told in the first person, is quite simple: the narrator, a pilot, crashes in the Sahara desert and meets the little prince. The mysterious golden-haired boy tells the aviator his story, his native asteroid and his rose, his travels, and the people he met on his arrival on Earth, and the things he learned.

This novella can be, and is often, read to children. Yet, despite the fairy-tale tone and the many fantastical events, The Little Prince tackles deep themes like friendship, loneliness, human nature, or growing up. There are several layers of understanding, and, therefore, it can be read at any age. The philosophical and inspirational thoughts can be understood differently depending on the reader’s maturity. Wise and timeless sentences, like “It is only with the heart that one can see rightly, what is essential is invisible to the eye” for instance, despite their apparent simplicity, are the kind of quotes which stay with you long after you finished the book – the kind of quotes which may come back to your mind at the most unexpected times, just like Proust’s madeleine.

An analysis of The Little Prince can also be made regarding the general context in which the story was written and the author’s own life. Just like his character, Saint-Exupéry was a pilot and he did crash in the desert – an event that also inspired another novel of his: Wind, Sand and Stars (Terre des hommes). The three baobabs, “drawn with a sense of urgency” according to the author, that are devouring the small planet as they haven’t been cut soon enough, can symbolize the three countries of the Axis. Indeed, The Little Prince was written during the Second World War.

It is also interesting to note that the pictures contained within the book – watercolors drown by the author himself – are equally important to the story than the words themselves. There aren’t just nice pictures to make the book more appealing to children, they bear a real significance.

Anouilh, Antigone (1944)

Just like The Little Prince, Antigone was written during WWII, and that is not a trivial fact. Indeed, the events of the time urged Anouilh to rewrite the famous antique play by the Greek author Sophocles. As Anouilh said himself, in a quote that was used as the back cover for the first edition of the play:

“Sophocles’ Antigone, that I have read over and over again, that I knew by heart, was a sudden shock to me during the war, the day of the red posters. I have rewritten it my way, in the light of the tragedy we were then living”

Written and played during the Nazi’s censorship in France, the play has to handle ambiguity, to play with innuendos, and to trust the viewer/reader to understand the right message out of it. The play doesn’t give a clear cut between bad and evil, between Creon – who symbolize order – and Antigone – the young rebel. Yet, the numerous parallels between Anouilh’s rewrite and the historical context are clear. In the 1944’ representation, at the Théatre de l’Atelier, the costumes – made by André Brascq – are deliberately modern, just like Anouilh included references to modern objects like bikes or movies in his play.

Though the author points to the Red Posters – Nazi’s propaganda to discredit resistant fighters – as a source of inspiration, another element seems to have greatly impacted on Anouilh’s rewriting: Pierre Colette failed attack on collaborationist Pierre Laval and Marcel Déat. Just like Antigone’s, Colette’s actions were – or, at least, at the time, seemed – as futile and vain as they were (at least to some, and to Anouilh) heroic. In Sophocles’ play, Antigone’s fate was still hopelessly sealed.

However, Anouilh made a small, yet crucial change, concerning the forces and powers against which Antigone must fight. In the original play, just like in many ancient tragedies, human characters are fighting against the Gods or destiny – and they failed, because you can’t cheat with the gods, you can escape your destiny. In Anouilh’s version, the forces are not divine, but human. Creon, against which Antigone is fighting, isn’t a celestial conduit, he is just a man. Through him, Antigone fights – and loses – against human traits, like hubris, selfishness, fear, anger, and hypocrisy. However, the mechanism, despite being rid of any superhuman device, is just as implacable as in any other tragedies, antique or modern. The Chorus’s metatheatrical interventions and commentary show that well.

“CHORUS: The spring is wound uptight. It will uncoil itself. That is what is so convenient in tragedy. The least little turn of the wrist will do the job… The rest is automatic. You don’t need to lift a finger. The machine is in perfect order, it has been oiled ever since time began, and it runs without friction… Tragedy is clean, it is restful, it is flawless… That makes for tranquility… […] Death, treason, despair, they are already there, at the ready. The outbursts, the storms, the stillness. Every kind of stillness. The hush when the executioner’s ax goes up at the end of the last act. The unbreathable silence when, at the beginning of the play, the two lovers, their hearts bared, their bodies naked, stand for the first time face to face in the darkened room, afraid to stir. The silence inside you when the roaring crowd acclaims the winner—so that you think of a film without a soundtrack, mouths agape and no sound coming out of them, a clamor that is not more than picture; and you, the victor, already vanquished, alone in the desert of your silence. That is tragedy.”

Beyond the historical relevance of the play, Anouilh plays masterfully with the ancient codes of tragedy – the chorus, the relentless mechanism crushing the characters, the notion of hubris… – as he manages to both point out the long-lasting relevance of such devices and to bring them up to date.

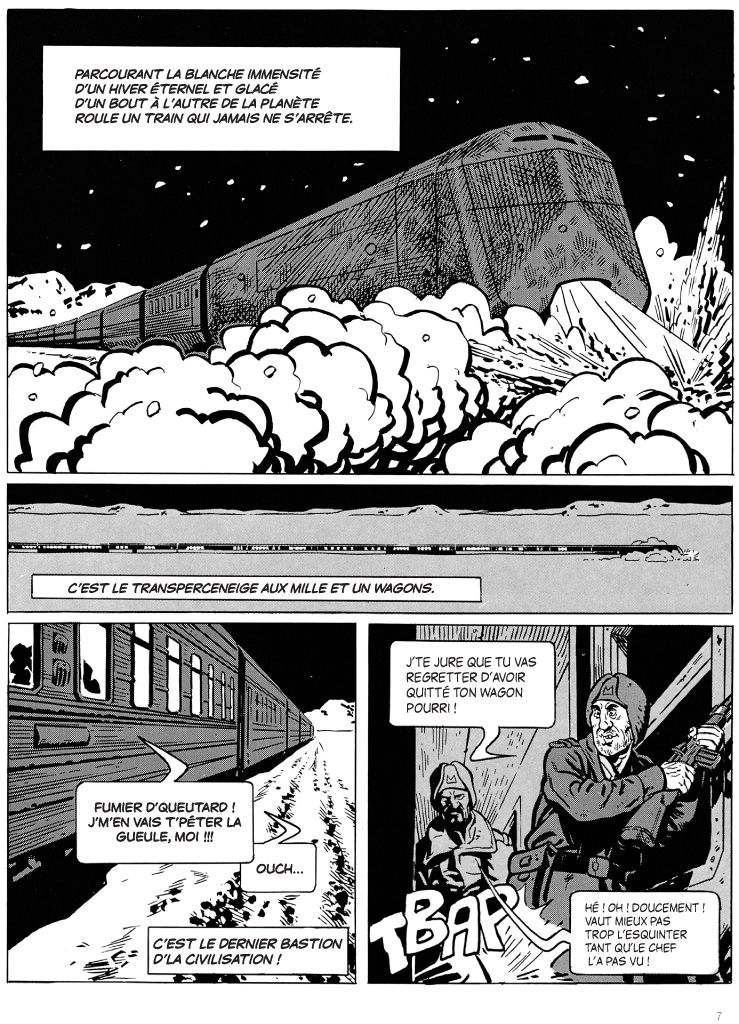

Jacques Lob and Jean-Marc Rochette, The Snowpiercer (1982) (Le Transperceneige)

The title may remind you of something. Yet, before being a successful movie, under Bong Joo-ho’s direction in 2013, and before being a Netflix show, Le Transperceneige was a French comic book, written by Jacques Lob, drawings by Jean-Marc Rochette, and published in 1982.

Following a cataclysmic natural disaster that causes an ice age, the remaining of the human race are forced to take shelter in a gigantic train of 1001 cars that circles the Earth without ever stopping. Life onboard the Snowpiercer is strict and highly ordered. The rich and wealthy occupy the first cars, while the poorer have to survive in the last cars. In this dystopic setting, we follow Proloff, a man belonging to the rear cars, who already rebelled against the hierarchy, and want to reach the first cars at all costs and the so-called “Holy Locomotive”. Throughout his quest, he discovers the last remnant of the “world of before” that the wealthy jealously kept to themselves.

The comic book tackles classic themes of dystopic sci-fi, to construct a harsh criticism of a society marked by growing individualism and capitalism, though the book also hints at a few inherently human traits. To go with the narrative, cold and dark strokes and drawings entirely in black and white. Interestingly, the illustrator, Jean-Marc Rochette, wanted to be a mountain guide, but an accident forced in to give up alpinism.

Oksa Pollock (Anne Plichota and Cendrine Wolf)

This one is a series of 6 books, the first one being called The Last Hope (L’Inespérée). The saga, translated into more than 20 languages, is often compared as the French equivalent of Harry Potter.

Just like the British saga, Plichota and Wolf introduce the reader to a fantastic universe, as magic as it is dangerous, that the characters – young teenagers for most – have to discover. Indeed, 13-year-old Oksa Pollock is not a normal teenager, like she thought. As the series begins, Oksa is still overwhelmed by her recent moving from France to London. She just wants to hang out with her best friend, Gus, and get through middle school. But, stressed by the start of the school year and by the strange attitude of her new math teacher, Oksa begins to trigger strange phenomenons. Soon, her eccentric grandmother, Dragomira, reveals to her the Pollock’s family is actually from a magical world, called Edefia, and which was once governed by Oksa’s great-grand-mother. Along with other fighters and members of the ruling family, the Pollock had to flee from their world when Occious, a tyrant, took power. But Oksa isn’t just one of the so-called “Runaways”, she is their last hope to see Edefia again.

Though most of the first volume takes place in our plain world, the authors still manage to immerse the reader in their universe. Firstly, of course, Oksa, as well as her father and grandmother, have powers and she learns to control them. Then, the Pollocks are a very fun and eccentric family despite all the tragedies they when through, and the characters are very endearing. But the main reason for this immersion is that the Runaways did not run away empty handed, they managed to salvage magical tools and objects, but also creatures from their world. As eccentric as the elder Pollock, we encounter numerous creatures with crazy names, crazy behavior or twisted way of talking. It also added a new layer of difficulty for the translator! On that note, there is an excellent article on Sue Rose’s work as a translator that sums up pretty well Oksa Pollock’s complex and rich universe. Here is a short extract:

Lunatrix and Lunatrixa: the French—Foldingot and Foldingote—is a combination of “foldingue” (crazy) and “dingo” (nutcase). […] What I came up with was Lunatrix, which is a combination of loony (since they’re crazy little characters) and tricks (for their weird abilities and the tricks they always have up their sleeves). They also have very large, moon-like, eyes so the first part of the name sounds like “lunar”, which relates to the moon. It was then easy to add an “a” on the end to make the female form. […]

Then there was the mud run of the “Lunatrixish” dialogue. The Lunatrixes speak in a very complex way, which is totally at odds to the simple language usually found in the Oksa Pollock books. The authors use this to show how strange and fascinating these cute household stewards are. Sometimes my eyes and ears became so clogged up with mud that it was hard to tell exactly what the Lunatrixes were saying—something that Oksa struggles with too!

“Here is a typical example: “The lineage of the Lunatrixes has preserved the recollection garnished with warmth of your erstwhile consent to cradle his body and lavish caresses on him”. All the Lunatrix is saying is that his toddler has remembered being cuddled and stroked by Gus — but the French is very difficult to understand and does not sound like everybody else’s normal, chatty way of speaking, so I had to do the same thing in English and make the language just as peculiar.

There is something almost Caroll-esque to Plichota’s and Wolf’s world.

Just like Harry Potter, with each passing book, things get a little darker, as if the reader were growing up with Oksa, Gus, Tugdual, Zoé… There is even a spin-off, to the saga, centered around the character of Tugdual and named after him. This new trilogy is definitively darker than the original saga, though just as enjoyable.

… And that’s it! Happy reading!

On a more serious note, one may ask why there is no mention of French authors like Flaubert, Zola, Balzac, or Jules Verne. Such a list is, obviously, partial and can’t encompass a whole literature. Yet, the selection here, though partial, tried to focus on less-known authors or works, and Flaubert or Verne seem to have crossed borders pretty well on their own.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Les Liaisons dangereuses, a magnificent book about moral values showing the decadence of the French aristocracy on the eve of the French Revolution.

A long time ago I watched the movie and it became one of my favorites but I hadn’t read the book. This was the reason why I had a slow start since I pretty much felt I already knew what was coming… and I did but it was so much better.

I think what’s stayed with me most since watching/reading the story is the pity I feel for the utterly morally, emotionally, spiritually and intellectually bankrupt lives everyone but the Michelle Pfeiffer character lead (sorry, I don’t have the book in front of me and can’t remember the character’s name).

i just finished this book last night. i laughed out loud so many times on the subway that people must think i’m crazy.

Honestly, I thought this book would never end.

SO GOOD. I wish more people knew about Paris Spleen.

In search of lost time was strange and rambled the way a Virginia Woolf novel does, but I found it easier to connect with.

I love everything about these books – even the rambling and the way in which characters are accidentally revived from the dead to appear in book 6 that were killed off in book 2.

This book should be in drawer of the bedside table of every hotel room.

I’m not sure if Albert Camus is pro Meursault’s purposeless joyful existence or not? I’m not sure if he’s punishing Meursault for his ways with the fright of dying so sudden and so bleakly like that? Or he is just portraying and protesting to the world’s unfairness and swift anger against anything and anyone that does not take life as serious as expected from any norm-abiding human being?

That is an interesting question!

Personally, I’m not sure Camus’ goal is to take position, either with or against his character. Though, in the preface to the American edition, Camus admits that, with some irony, he does care for Meursault, with the affection an author can feel for his character. (I couldn’t find the text in English, so this is a rewording).

In this same preface, he explains that the question to ask is not why Meursault refuses to play the “game”, but how does he refuse, by what means does he refuse the “game”. To that, Camus answers: he refuses to lie. He refuses to lie about everything, and especially about the “things of the heart” (once again, it is a paraphrase) and the small lies, the small omissions or additions to make life easier we – as a society – say or demand. We could see there a kind of heroism in the character. However, Camus adds that this passion for absolute and truth is a negative search, of a negative truth. Camus doesn’t see Meursault as an “empty wreck”, but as a “poor and naked man”.

To me, Camus’ goal isn’t to punish anyone or protest against anything, but ‘simply’ show the mechanism of this Absurd, but I may be wrong… That is a very interesting question, anyway! Thank you!

L’Étranger is amazing.

A powerful novel with an even more powerful ending.

Definitely my favorite book. Story of the life.

YES! The Little Prince. My stomach felt like I was on the drop of a rollercoaster at some points while reading this, and I could actually feel my heart beating out of my chest, no exaggeration.

This little book contains words of immense wisdom.

I got lost in all his symbolism and it made me feel too stupid.

Molière really needs to be seen in the original language. No one really captures the lightness of touch that French-speaking actors have.

One of the funniest plays I have ever seen was L’Avare, with in the lead role, the inimitable Jean-Claude Frison at the Théâtre Royal du Parc in Brussels. In fact this theatre, together with the Théâtre National is instrumental in keeping the great Molière classics alive and relevant. They also do a mean Racine.

I have seen Molière plays performed in English but somehow they just don’t work as well. The French gift of conveying subtle satire is missing.

I’ve only read and seen Molière in French, but I can get why his plays may not be as good once translated into another language. (It goes both ways, of course, I’m sure Shakespeare in the original language is way better and enjoyable than a translated Shakespeare!)

I agree L’Avare is so good! I also deeply enjoy Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme!

Thank you for your passionate comment!

I haven’t read any of these texts you discuss, nor have I even heard of most of them. But, the passion with which you write of them has definitely encouraged me to check them out! Great article. 🙂

Thank you very much! I’m glad I could introduce you to French literature! Happy reading! 🙂

Great list. For a real skit read ‘Voltaire’ or even our own ‘Tom Paine’ ,or better still the eloquence of Compte du Mirebeau; who the French Revolutionaries were afraid of, more than the Guillotine, or Rapier.

The way Molière satirises social climbers is highly amusing.

It is!

I absolutely loved The Litte Prince. Though it’s a children’s book, I wouldn’t necessarily recommend it for kids.

I fell to thinking about this book again when I was out for my evening walk, since I have been with no great care attempting to time it to catch sight of a fox.

Children will not understand the metaphors and allegories in this tale.

Books in France can, in a very literary sense, be extremely lightweight. The French are as polite and charming as ever, and their language is beautiful, but as far as a good read is concerned, the Anglo-Saxon world provides infinitely more quality.

I would tend to disagree on that point. What do you mean by a “good read” and “quality”? I’m not at all trying to argue that French literature is ‘better’ (or ‘worse’) than other literature, as I have no legitimacy to do so! I am, however, curious about which criteria you base your comment on. Could you develop?

If you’re talking quantity (“infinitely”), the Anglo-Saxon world is vaster than sole France, of course, so, statistically speaking… We could also argue that Anglo-Saxon literature is, at least today, more covered in the media on a world scale than French literature. The time frame or the genre could also be an argument, going one way or the other. How literature is taught in both areas could also be a part of the debate! There is an interesting discussion there!

Though I personally don’t think you can place one literature above another that easily, targeting one specific aspect of literature and comparing countries or languages may be an interesting, though complex, exercise!

I presume you mean “in a very literal sense”. I’ve found French writers manage to pack as much literary and philosophical weight into 100 pages as many American and English writers do in 400.

Albert Camus is a writer who has taken up with more decision and clarity, than any other writer that I have read till now.

I feel like The Stranger is Beginner’s First Book on Absurdism.

Well, it is Camus’ first book within his “Cycle of the Absurd”!

A fan of Albert Camus, I was surprised at how much I didn’t like this book. I found it frustrating, boring, and rather depressing.

In Search of Lost Time was the first fiction I read in years that had that same charm for me that novels had when I was young. Thanks for the coverage.

There is something very “romanesque” and teeming to it, indeed!

The greatest work of literature I’ve ever read – a strong sentiment, but one I honestly feel.

I love Baudelaire.

Baudelaire’s style and poetics aren’t simple. And that’s not a bad thing.

The most interesting part of the stranger book to me was conversation with priest especially at the end of it conversation.

The conversation with the priest is, indeed, rather striking!

The Little Prince is so beautiful, yet it’s hard to understand.

How so? (I’m not denying it can be hard to understand, but I’m curious to know where/how/on what aspects you find it hard to understand!)

It explores a lot about ourselves and what we value. I was in tears at the finish.

My favorite children’s novel ever; utter perfection.

I don’t know how children bear this story, too many tears. Beautiful writing.

Had to read (well in my case re-read) The Little Prince for my poetry class. I must say what a beautiful story! The writing was just spectacular! Thanks for reminding me of it. Loved it.

I liked your description of Racine and Molière because it gave a nice broad overview of how he wrote. I definitely saw the antiquity being conveyed by Racine when I read Phadre. I also enjoyed that you introduced Mithridate to me and gave me a reminder that both Molière and Racine are influences on my own fictional writing. Good job and thanks for the article!

I’m glad you like them! Racine is a master at reviving Antiquity, indeed!

You are a writer, then? That’s awesome!

My pleasure! And thank you very much, for reading, for this kind comment, and for your help during the editing process!

Trés bon!

Merci beaucoup! 🙂

Every Camus novel leaves you drained from the experience of consuming all thoughts in reading one. It leaves you in a state of happy existence.

I didn’t like The Stranger initially but gradually it made me think deeper and did impact me.

The Stranger. I read this masterpiece in French.

Love Molière. I saw a production of ‘Tartuffe’ a few years ago – translated by Ranjit Bolt – and it was hilarious, one of the best things I’ve seen at the theatre. I’d love to be able to understand it in the original, but I Moliere is absolutely worth seeing in any language.

Wonderful long list to get started with!

Thank you very much! I hope you’ll enjoy the reading!

So many wonderful books listed here! I absolutely adore The Little Prince and l’Etranger! 🙂

Adding these to my TBR, so much French has escaped my radar.

For Camus I would also recommend The Myth of Sisyphus and The Plague

They’re great books too, indeed. The Plague (La Peste), may also be, in some ways at least, quite relevant regarding the current covid-19 pandemic!

Thank you for the informative and passionately written article. I am now encouraged to check more French Literature.

Beautiful article with really unique selections I wasn’t even privy to!

I picked up La Peste by Albert Camus a couple months before the COVID-19 pandemic, and I found he’s an author with a more profound understanding of the human condition than most. As the real plague progressed, I kept finding similarities between fiction and reality with the novel’s townspeople going to the café to try and revisit a semblance of old life, with the Californians around me doing much the same at the time. And in the political administration we were in, Camus’s absurdist philosophy certainly provided an effective framework to deal with everything happening.

Thank you very much!

The Pest is a very deep and interesting book, indeed, especially during the current pandemic! I completely agree! On that subject, in France, The Pest was among the highest book sales of the first lockdown!

If you read The Stranger, I hope you’ll find it as much enjoyable!

Thanks again for your comment!

Antigone was very interesting

I am in the middle of reading Zadig from Voltaire. I just finished Candide which I enjoyed quite a bit, but I have not enjoyed Zadig as much, and now you tell me I have to read another piece from Voltaire. That aside, your eye for what readers will actually engage with here is very helpful, to recommend someone to read Hugo’s major works may be a bridge to far, but to recognize that and recommend a short story is a great move.

To be completely honest, I only read extracts of Zadig, but I think I would still prefer Candide or Micromegas too!

Interestingly, I recently had a talk with a friend about how it may be easier to start reading famous and classic authors through their short stories, or their less-known works!

Thank you very much for your comment!

Avec grand plaisir! Quels sont les titres qui t’intéressent le plus, si ce n’est pas indiscret ?

(My pleasure ! What would be the titles you’d be interested in, if that’s okay to ask?)

Thanks for such an insightful article.

I was disappointed when Queneau or Perec didn’t make it to the list.