Artificial Intelligence Goes to the Movies

For nearly sixty years, or the length of time that the disciplines concerned with artificial intelligence first emerged, popular culture in the form of film, literature, and video games has given us various scenarios about how and why artificial intelligence (hereafter A.I.) might come into being, how these A.I. entities might relate to their human creators, and how they would act in both the natural and cultural world. From Isaac Asimov’s three laws of robotics, introduced in his 1942 short story Runaround, to Robert J. Sawyer’s 2005 novel Mindscan, from the HAL 9000 A.I. in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey to the 2014 movie Transcendence, film-makers and writers have, with varying degrees of lucidity, explored in dramatic form just what the creation of an A.I. entity might mean for human beings and the world we inhabit.

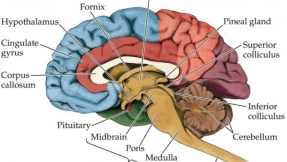

From a scientific perspective, the investigation of the mind, which is obviously at the heart of artificial intelligence, is known as cognitive science (at least since the 1970s), and “is an interdisciplinary field of research comprising psychology, neuroscience, linguistics, computer science, artificial intelligence, and philosophy of mind…Cognitive science, although institutionally well established, is not a theoretically settled field like molecular biology or high-energy physics” (Thompson, 2007).

In movies and in literature, there have been two ways of going about creating artificial intelligence. By far the most common is for human beings (although it is sometimes an alien race), to build some sort of super-computer which, because of its complexity, and perhaps some unknown factor, achieves both a state of consciousness and also a state of self-awareness (the two are not the same; a being can have consciousness and not be self-aware). In this manner, the computer or android or cyborg or whatever the embodied form achieves a mental capacity greater than that of any single human being – and in certain cases greater than the sum total of all human beings presently alive.

Again, usually, though not always, these conscious A.I. entities immediately want to either destroy the human race or place them in positions of servitude. Why this is so remains an ongoing mystery; it is neither self-evident or a necessary stage of A.I. evolution that they should develop the desire to destroy or enslave their human creators. This plot device might be inherently more dramatic, but it remains a source of unexplained perplexity as to why one would expect A.I. entities to engage in this sort of violent, anti-human behavior.

Here is a sample list of A.I. based movies, or movies which featured A.I. entities, in no particular order: Transcendence; Her; 2001: A Space Odyssey; WarGames; A.I.; I, Robot; Westworld; The Matrix Trilogy; The Terminator series; Forbidden Planet; Star Trek: Next Generation movies and television; The Day The Earth Stood Still; R2D2 and C-3PO in Star Wars; the Transformers series; Blade Runner; and the first robot to be depicted in film, Maria, who is a Maschinenmensch (machine-human) in 1927’s Metropolis.

What applies to most of the movies listed above is both the fact that they are created by human ingenuity but also develop, or created with, nefarious purposes towards their makers: the Reapers in the 2007 video game Mass Effect, Hal 9000, Skynet, Westworld, The Machines in The Matrix, the Nexus-6 androids in Blade Runner, et cetera and apparently ad infinitum.

For the most part, and especially so in film, there is no explanation as to how the computer gained consciousness, which would be the essential first step towards an explanation of why these A.I. beings act in the way they do. Likewise, there is little to no explanation as to what consciousness ‘embodied’ in a machine might mean, other than a stock “that was how it was built.” In 2001: A Space Odyssey, Hal 9000, after he’s gone psychotic and while Dave is trying to kill it, tells Dave that “I am a Hal 9000 computer. I became operational at the HAL lab in Urbana Illinois on the 12th of January 1992. My instructor was Mr. Langley and he taught me to sing a song” (Kubrick, 1968). This is the sort of (non) explanation usually provided for the creation of the A.I. entity. (It’s also interesting that in 2001, the director Stanley Kubrick gives the most coherent and insightful answer as to why the A.I. – HAL 9000 – went psychotic, though it is not explicitly stated in the film. Kubrick said in an 1969 interview that “the idea of neurotic computers is not uncommon – most advanced computer theorists believe that once you have a computer which is more intelligent than man and capable of learning by experience, it’s inevitable that it will develop an equivalent range of emotional reactions – fear, love, hate, etc. Such a machine could eventually become as incomprehensible as a human being, and could, of course, have a nervous breakdown – as HAL did in the film” Gelmis, 1970, p.95.)

Much rarer, and theoretically more difficult to explain, are those A.I. entities who owe their intelligence to human consciousness. In the 2009 movie Avatar, Jake Sully, the hero, has his mind, at the end of the movie, uploaded into the mind of the planet, Eywa, and then back into his Avatar body. In the original Tron (1982), Flynn, a human computer programmer, is taken by an A.I. entity called “Master Control Program,” digitized, and brought into the virtual world of the computer. In The Lawnmower Man (1992), scientists boost the intelligence of the character Jobe through various means. After he becomes hyper-intelligent, he transfers his mind completely into virtual reality, leaving his decayed mortal body behind. In Transcendence, the most recent movie to deal with A.I., Dr. Will Caster is dying from acute radiation poisoning, and his wife and friend Max upload his consciousness to a quantum-computer.

In literature, the results have been in the main more successful. As noted above, Isaac Asimov formulated the three laws of robotics in 1942. Before that, the Czech writer Karel Čapek first used the term ‘robot,’ in his 1921 play R.U.R. This play revolves around a race of self-replicating robot slaves that revolt against their human masters, a rather obvious allegory of the status of the proletariat in modern, capitalist society and the hope that “Working men of all countries, [will] unite!” (Marx & Engels, 1969, p. 11.)

Frederick Pohl, in 1955, published a story about a human consciousness that had been uploaded to a robot and didn’t realize that it was a robot (The Tunnel Under the World.). Arthur C. Clarke, in his novel The City and the Stars, 1956, deals with mind-uploading, immortality by computerization and cloning, and human-machine symbiosis. Throughout Iain M. Banks’s science fiction novels in “The Culture” series, the uploading of minds, the nature of minds, and the relationship between mind and body is extravagantly, humorously, and brilliantly used. Two that stand out are Feersum Endjinn in 1994 and Excession in 1996. In the previously mentioned novel Mindscan, Canadian author Robert J. Sawyer fully incorporates present ideas about uploading consciousness, what this would entail, how it would be done, and the nature of a consciousness in an android body.

Mention should also be made of William Gibson, who bridged both the media of literature and television. In in his ground-breaking novel Neuromancer (1984), Gibson created an A.I. entity called an “artificial informorph.” He also co-wrote an episode of the X-Files television series, Kill Switch, aired in 1998, where a woman seeks to upload her consciousness into the internet in order to join her lost love, who has already uploaded his consciousness to the net. This episode by Gibson and co-author Tom Maddox is smart, internally consistent, funny, horrifying, and simultaneously touching.

One could also argue that in the mid 20th century there were a spate – okay, several – movies that tackled the notion of how we might preserve consciousness in those who were dying, or already dead, albeit on a more primitive level: actual brain/head transplantation. We get, in 1953, Donovan’s Brain, which is probably the best of the lot. And then: The Head, 1959. The Brain That Wouldn’t Die, 1962. The Atomic Brain, 1964. And on everyone’s list of favorites, the 1961/1968 classic They Saved Hitler’s Brain. In an ever more scientifically knowledgeable audience, the idea of cutting off someone’s head, preserving it in some sort of electric-chemical bath, and then re-transplanting it onto a different body probably became a bit too ludicrous (although the movie Re-Animator, 1985, has achieved a sort of cult status). Why not just transfer the consciousness and do away with the whole messy brain/head transplantation, loss of blood, deprivation of most of the central nervous system, and nerve regeneration and reconnection problems?

In either case, whether the A.I. entity is created by humans, or aliens, or a mind is uploaded into a computer, the difficulties that arise around the idea of intelligence and consciousness are mainly ignored, while the uploading or creating is taken for granted. As HAL 9000 says, he was built at a certain time, instructed, learned a song, and that’s about it. How can a formerly embodied consciousness – as in Dr. Will Caster’s in Transcendence – be uploaded into a computer, even in a cutting edge quantum computer?

Furthermore, would the intelligence and consciousness transferred from the living human being into some sort of computer/android body remain the same? Does it matter that what we call mind, a sort of general catch all for intelligence, consciousness, self-awareness, emotions, desires, and intentions moves from a substrate of organic neurons, axons, dendrites, myelin sheaths, synapses, and electro-chemical reactions to a substrate of inorganic matter, including silicon, silicon ‘doped’ with boron or arsenic, copper, hafnium, and gold – and that’s just for the cpu. The hard disks that store the data are made up of another range of inorganic materials, such as aluminum, magnesium, zinc, and nickel. How are the these “things” we place under the umbrella of mind, which emerge from and depend on organic matter, transferred into an inorganic, metallic, or metalloid substrate? Why should we accept the implicit claim that uploading an organic consciousness to an inorganic computer is simply a future fact?

Uploading Consciousness

The movie Transcendence serves as a useful starting point and example, as it is the most current, to explore the nature of artificial intelligence. The explanation as to how they can transfer Dr. Will Caster’s consciousness into a quantum computer is given by his wife, Evelyn (Rebecca Hall). One of the Casters’ co-workers on A.I. is Dr. Casey, a scientist who has been working on uploading the consciousness of a Rhesus monkey into a computer. He is killed during a series of attacks on all the A.I. research centers around the U.S. by an anti-technology terrorist group, known as R.I.F.T. (Revolutionary Independence From Technology), but his notes have been sent to Will and Evelyn.

Evelyn, after sifting through the notes, says to Max, her friend and cohort in A.I. research: “It’s all built up in Casey’s solution to the self-awareness problem. He did it six months ago. Instead of creating an artificial intelligence he duplicated an existing mind.”

Max: “Tell me you’re joking.”

Evelyn: “He recorded the monkey’s brain activity and uploaded its consciousness like a song or a…His body is dying but his mind is a pattern of electrical signals that we can upload into PINN [the name of the quantum computer they have built], we can…”

Max: “…Ev, he’s not a monkey! Assuming that implanting an electrode into his brain doesn’t actually kill him, and this works, at best you’ll be making a digital approximation of him. Any mistake – anything, a thought, a childhood memory…How will you know what you’re dealing with?” (Pfister, 2014).

Well, that’s certainly something that nobody has ever thought of before. Just record the electrical signals emitted by the brain and upload them like you would a song! What could be easier? What could possibly go wrong? And the self-awareness problem? Solved? Does a Rhesus monkey even have self-awareness? Granting it consciousness is one thing, but self-awareness entirely another.

Two ideas are conflated here: one is simply wrong and the other never addressed.

First, the simply incorrect. According to Evelyn, the mind is nothing other than the brain; that it functions is a result, apparently, of the electrical signals it produces. Even if you think that the mind is the same thing as a brain, or is produced by the matter and activity, in the form of electro-chemical reactions, that constitute the brain (which is hardly a given), the notion that it can be uploaded by capturing produced electrical signals makes no sense, however innocent or naïve you want to believe the characters are. But these characters are not naïve – they have been working on this for their entire professional lives. Evelyn must know that consciousness is not a digital version of a digital song; Max also indicates he knows it (“Ev, he’s not a monkey!”). And what the writer and the director should know is that we know it as well. One doesn’t have to be a neuroscientist to have a basic understanding of the brain.

As any one who has taken a high school biology class knows, the brain consists of various cells, chemicals, and electro-chemical reactions. The cells that do the heavy lifting are called neurons – and there are approximately 100 billion of them in a human brain. Everything that is produced by the brain – thoughts, sensations, memories, emotions, etc. – are the result of signals that pass through neurons to different parts of the brain. In passing the signals along – through synapses, or the space between the neurons – the end of the axon (the part of the neuron leading to another neuron) releases a sac of chemicals called neurotransmitters. The synapses are the important functional aspect of the brain. It is estimated that the human brain contains approximately 200 trillion synapses. When a signal crosses a synapse, the released chemicals attach to receptors and change the properties of the receiving cell. These chemicals, or neurotransmitters, are widely known; we have synthesized pharmaceuticals which mimic their behavior and affects, and are used to treat depression, bi-polar disorder, Parkinson’s disease, and other mental ailments. The most common neurotransmitters are serotonin, dopamine, GABA, and acetylcholine (NIH, 2014).

The above description is a much simplified account of how and what the brain does, and what every American youth learns in high school, if not earlier. And this simplified explanation should be enough to make clear that one cannot simply record the electrical signals of the brain and upload that recording into a computer. Stuart Russell, co-author of the standard textbook on A.I. called Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, writes in an essay on the movie that the idea that we could capture that many connections and states is “a non-starter” (Russell, 2014).

If you believe that consciousness is identical to the brain’s matter and its activity, then you would, as Max suggests, have to upload everything in order to reconstitute that particular consciousness. Every neuron and every synapse. Every axon and every neurotransmitter. Every electrochemical process in the brain, both where it takes place and when it takes place in relation to every other electrochemical process and state. Evelyn is even fundamentally wrong when she says that by recording the electrical signals we can capture the consciousness of Will Caster. The electrical impulses we record, most commonly through an EEG, are a side effect of the electrochemical processes taking place within the brain. If a large enough area of brain tissue generates an electrical field, then that field can be detected outside of the skull. This is what Max must mean when he says that they will have to implant an electrode into Will’s brain.

In Robert J. Sawyer’s novel Mindscan, the uploading problem is treated in at least a seemingly much more plausible manner. A representative of the company Immortex explains the process: “Our patented and exclusive Mindscan process is nothing more daunting than that (an MRI), although our resolution is much finer. It gives us a complete, perfect map of the structure of your brain: every neuron, every dendrite, every synaptic cleft, every interconnection. It also notes neurotransmitter levels at each synapse. There is no part of what makes you you that we fail to record.” Furthermore, the process “that we use [is] quantum fog to do our brain scans. We permeate your head with subatomic particles – the fog. Those particles are quantally entangled with identical particles that will be injected into the artificial braincase of the new body” (Sawyer, 2005, pp. 19-20 & p. 43).

The point here is that consciousness, which we will examine shortly, is both a “reality” that defies easy explanation and a concept that, as we try to explain it, proves elusive to scientific explication. Transcendence, as the latest popular movie on A.I., will serve as a reference point when we examine the ideas surrounding artificial intelligence, including the concepts of intelligence, artificiality, consciousness, brain-imaging, embodiment, and the nature of perception.

Artificial Intelligence (A.I.)

Artificial intelligence is usually described as the creation of a machine (in modern terms a computer, or an android that houses a computer) that has intelligence. Obviously. The first difficulty that those who work in A.I. encounter is this: what is intelligence? Is intelligence simply processing power – i.e. computing? Is it a matter of calculating using abstract, logical rules? This has been the overarching belief and paradigm informing A.I. research since it began in the early 1950’s: human intelligence is, like a computer, computational. Mental activity – cognition – takes place when information is provided by an environment; that information is formed by the processes of the brain into representations; and those representations can then be processed to provide logical responses in terms of action.

If that is how one defines intelligence, there is no doubt that most computers can vastly outperform their human counter-parts: they can calculate much more quickly than a human can and do so with much more complexity and accuracy. This ability to brute calculate was made publicly manifest when a computer – IBM’s Deep Blue – defeated the reigning world chess champion Garry Kasparov 3 ½ to 2 ½ games in 1997, playing under the normal rules of tournament chess. In fairness to Kasparov, he made a critical error early in the opening of game six which placed him in an unfavorable position on the board. He then seemed to give up: “I was not in a fighting mood,” Kasparov said about game six. “I’m ashamed at what I did at the end of this match. I have to apologize for today’s performance. I’m human” (Fine, 1997).

I don’t believe that the sheer calculating power of a computer, and surely not one as sophisticated as Deep Blue, is disputed. Likewise, and even more impressively, IBM built a super-computer in 2011, called Watson. Watson’s raison d’être was to play the television game show Jeopardy!. In this case, Watson had to be capable of understanding questions (in Jeopardy! terms, answers) posed in natural language. Watson did this by executing thousands of proven language analysis algorithms simultaneously to find the correct answer. The percentage likelihood of the correct answer depended upon how many of those separate natural language algorithms came to the same answer independently of each other. In a sense, this is brute calculating power, done with multiple natural language analyses running simultaneously instead of an original algorithm designed for playing chess.

But the ability to understand natural language, and the ability to come up with the correct answer, adds something more to Watson. It makes Watson more human-like. After all, human beings spend much of their waking lives talking (of course, they might talk in dreams as well) – we talk about our children, co-workers, sports, movies, siblings, the weather, vacations, books, crime, gardening, weight, neighbors, politics, parents, religion, cars, television, dentists, email, birthdays, the internet, disease, music, insects, health…and on and on and on. Because Watson could do this (in the context of the game), it seems to impart to Watson something Deep Blue does not have. If human beings are the sorts of beings who can speak and understand one another, given a common language, then why not consider Watson as a member of our select group? And, in the end, Watson, who competed against two former Jeopardy! champions (both human), won the game decisively.

Nevertheless, the claim that Watson’s, or any other computer’s intelligence is the same as human intelligence still faces considerable difficulties. This could be seen in several of Watson’s strange answers to several questions. For example, Watson was the only contestant to incorrectly answer the Final Jeopardy! response in the category of U.S. cities. The question was: “Its largest airport was named for a World War II hero; its second largest, for a World War II battle.” The correct response is “What is Chicago.” Watson’s answer was this: “What is Toronto.” Watson’s difficulty in answering this question has been attributed to the context specific nature of the answer and Watson’s inability to understand the comparative knowledge necessary to answer correctly. Most artificial intelligent programs suffer from the same problem – they are very good when asked about items in the umbra of their programming, but when one steps outside of the code, they tend to produce strange results. Professor Eric Nyberg of Carnegie Mellon University, who worked on Watson with its IBM creators, said that “A human would have considered Toronto and discarded it because it is a Canadian city, not a U.S. one, but that’s not the type of comparative knowledge Watson has” (Robertson & Borenstein, 2011).

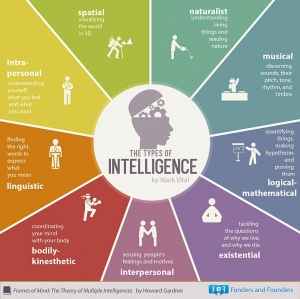

Again, we have to ask what is meant by intelligence. The problem here is that intelligence does not simply mean the ability to compute input from an environment into suitable (logical) actions. The meaning of intelligence spills out of this definition, seems to contain within itself a multiple number of meanings, and meanings moreover that we usually parse out depending upon the context in which they are used. So, for example, intelligence can mean the ability to use logic, or logical rules, to solve problems. This is Deep Blue and Watson. But intelligence can also mean understanding, self-awareness, learning, communication, emotional knowledge, and memory. Sequential, human programmed computer or information processing machine – both do not do justice to what intelligence is. And looking to standard dictionaries does not help, since the definition is usually something like “the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills.” What kind of knowledge and how do we acquire it? What kind of skills? And how do we know we have acquired this knowledge? If one didn’t know beforehand what knowledge was, how would one know what it is if one found it?

The difficulty in defining intelligence can be seen from a different perspective: what, precisely, do intelligence tests measure? Or, even more telling, what do they not measure? According to Ian Deary, “intelligence tests do not measure: creativity, wisdom, personality, social adroitness, leadership, charisma, cool-headedness, altruism, or many other things that we value” (Dreary, 2001). From this view, simple intelligence is a limited capability which does not capture the full range or extent of what we call the mind.

And lest we think we are the first ones to grapple with the problems raised by artificial intelligence, it would behoove us to remember that the ancients, especially Plato and Aristotle, also discussed at length these very questions. The dilemma about knowledge, for example, is the dilemma described in Plato’s dialogue Meno: “How,” Meno asks, “will you search for it, Socrates, when you have no idea what it is? What kind of thing from among those you are ignorant of will you set before yourself to look for? And even if you happened exactly upon it, how would you recognize that this is what you did not know?” (Woods, 2012.) Even if we look to its Latin roots – intelligere – we still have to interpret what is meant by “comprehending” or “perceiving,” the usual translations of the Latin word. The same is true for the Greek word nous, which the Latin encompasses, and which was described in excruciating detail in the Christian tradition, from Augustine to the medieval scholastic thinkers.

As a terse example of the difficulties of defining intelligence, and hence knowing when something that we create, something artificial, possesses intelligence, let’s look at the use of the Greek term nous as Aristotle explains it in On the Soul and in the Nicomachean Ethics. In these works (and others, such as the Metaphysics), Aristotle is at pains to make an accurate account of human reason. In this process, he claims that we can mean reason in four distinguishable ways. Human beings, provided they have been taught, recognize four capacities of the soul which can discover, or reveal, the truth. First, there is technical know how, such as the craftsman possesses. This is called technē. Two, there is knowledge that is logically deduced from facts or axioms – this is epistēmē, updated in the modern world and translated as scientific knowledge. Three, and this applies to ethics, we have the capacity for practical wisdom – phronēsis. Finally, we have the capacity for theoretical wisdom, or sophia, defined by Aristotle as a combination of epistēmē and nous. Nous itself holds an other, privileged place in Aristotle’s analysis.

“And intellect [nous] is directed at what is ultimate on both sides, since it is intellect and not reason [logos] that is directed at both the first terms and the ultimate particulars, on the one side at the changeless first terms in demonstrations, and on the other side, in thinking about action, at the other sort of premise, the variable particular; for these particulars are the sources from which one discerns that for the sake of which an action is, since the universals are derived from the particulars. Hence intellect is both a beginning and an end, since the demonstrations that are derived from these particulars are also about these. And of these one must have perception, and this perception is intellect” (Sachs, 2002, p. 114).

So, for Aristotle, there are at least four different kinds of intelligence, although primacy is given to nous, in that nous comprehends both the universal and changeless terms in relation to the changing particulars of experience. Nous fully takes in the “object of knowledge, in a manner that flexibly accommodates all the nuances and particulars,” and, furthermore, this is a “common-sense understanding that thought and experience are unified” (Robinson, 2008, pp. 8-10).

This manifold way of defining intelligence also became popular in the late 20th century, mainly through the work of the psychologist Howard Gardner. In several books, Gardner claims that we have multiple intelligences – a single category of “intelligence” (àla cognitive scientists) doesn’t capture the variety and richness of inner life. So, according to Gardner, we have a host of intelligences: intrapersonal intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, logical-mathematical intelligence, naturalist intelligence, spatial intelligence, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, linguistic intelligence, and musical intelligence (see the Multiple Intelligences website at http://multipleintelligencesoasis.org/).

His theory of multiple intelligences struck a chord, especially those with children or who work with children. He seemed to have captured what parents and teachers already implicitly knew: children have a wealth of different sorts of capacities, some do better at some things rather than others, and his not rigid classificatory system seemed to fit better with what parents and teachers were already seeing in their children.

Nevertheless, even if we grant these multiple intelligences (and, theoretically, it is possible that there can be more), or go back to Aristotle’s classification of reason and our mental life, we have come no closer in determining how intelligence emerges from the activity of the brain, how one knows whether or not one possesses intelligence, how one might know if another person or persons possess it, or how and if a machine actually possesses this ability.

In the history of artificial intelligence, the British born mathematician, cryptographer, and computer systems pioneer Alan Turing plays a decisive role in framing a modern conception of intelligence in relation to computers. Turing formulated his thoughts in a pre-computer age, the years following World War II. And it was precisely the logical difficulty in determining what we mean by intelligence, or reason, or thinking, that led him to conceive the question in terms of the behavior, or function of the machine, and not some predetermined, hazy definition of thinking or intelligence. In his seminal article of 1950 “Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” he formulates it this way:

“I propose to consider the question, “Can machines think?” This should begin with definitions of the meaning of the terms “machine” and “think.” The definitions might be framed so as to reflect so far as possible the normal use of the words, but this attitude is dangerous. If the meaning of the words “machine” and “think” are to be found by examining how they are commonly used it is difficult to escape the conclusion that the meaning and the answer to the question, “Can machines think?” is to be sought in a statistical survey such as a Gallup poll. But this is absurd. Instead of attempting such a definition I shall replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words” (Turing, 1950).

Turing’s answer to the question “Can machines think?” is, ultimately, to put it to the test. That is, we can pragmatically determine if a machine can think by engaging in the act of thinking. In Turing’s thought experiment, he envisions an interrogator conversing, vie teletype (instant messaging, today), with both a human being and a machine. The questioner cannot see either the human being or the machine and of course cannot hear either. If the questioner, in his conversation with both, cannot distinguish the two, or if he thinks the computer is a human, then, Turing says, the machine can be said to think.

The Turing test is now known as the annual Loebner Prize, backed by Hugh Loebner, who has offered a prize of $100,000 for the first computer whose responses are indistinguishable from a human being’s. In 2013, the A.I. program Mitsuku took first prize, although none of the four A.I. chatbots fooled any of the four judges. A chatbot is the term used to describe the computer programs which hold conversations with the judges. Many of these are available online – you can, for example, have a conversation with the popular A.I. bot known as Cleverbot (http://www.cleverbot.com). Despite the disclaimers on the site that Cleverbot is a software program, many believe that they are, in actuality, conversing with a human being.

Most A.I. researchers do not put much value on the test – both because of the test per se, and because of the direction A.I. research has followed since the 1980’s. In a well known exchange, Marvin Minsky, now a professor emeritus at MIT and known by his students as the father of artificial intelligence, wrote that he hopes Loebner will “revoke his stupid prize, save himself some money, and spare us the horror of this obnoxious and unproductive annual publicity campaign.” Neil Bishop, who organized the 2002 Loebner competition, explained why the Loebner Prize carries little weight with A.I. researchers: “In the professional and academic circles the term Artificial Intelligence is passé. It is considered to be technically incorrect relative to the present day technology and the term has also picked up a strong Sci-Fi connotation. The new and improved term is Intelligent Systems. Under this general term there are two distinct categories: Decision Sciences (DS) and the human mimicry side called Mimetics Sciences (MS)” (Sundman, 2003). For an excellent overall account of this annual competition, see Brian Christian’s 2011 book The Most Human Human, where he not only takes part in the test, but explores the deeper issues of how human beings interact and communicate in sundry ways with others and with the world.

Part of the reason A.I. researchers have moved away from the Turing test as a practical means of determining whether or not a machine can think lies in the history of A.I. research. From Turing through the late 1970’s, there was a great deal of hope, an optimistic belief that we would be able to create such an intelligent machine. This view is known as “strong” A.I., where a machine could be created which was virtually indistinguishable, in its mental capacities, from a human being. This is also the position of the movie Transcendence, as the A.I. entity is clearly seen as not only equal to human intelligence but better, as well as possessing the emotional range of human beings.

Roughly, from the early 1980’s on, the growth of applications to real-world problems boosted A.I. research, and companies began pouring money into it. In the standard textbook Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, by Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig (3rd Edition, 2010), the authors note that the A.I. industry “boomed from a few million dollars in 1980 to billions of dollars in 1988, including hundreds of companies building expert systems, vision systems, robots, and software and hardware specialized for these purposes.” (Russell and Norvig, 2010, p. 24.)

As time went by, and no machine with anything near these capabilities emerged, there came a period known as the “A.I. Winter” – a time when many companies went bust as they failed to deliver on exaggerated promises. This A.I. funk led to a change in direction, where A.I. adopted adopted the scientific method, which, according to Russell and Norvig, led to “a revolution in both the content and methodology of work in artificial intelligence.” (Russell and Norvig, 2010, p. 25.)

Today, A.I. research and development has fragmented into various subfields, which have resulted in working applications. These include robotic vehicles; speech recognition software; autonomous planning and scheduling software; game playing (think Deep Blue); logistics planning software; and robotics. (Russell and Norvig, 2010, pp. 28-9.)

Despite these smaller successes, the promise of a strong A.I., one that nears the capabilities of human beings, has fallen to the way side, a fact bemoaned by some leading lights in A.I., including Marvin Minsky. What difficulties did those who believed in strong A.I. come up against that led them to abandon the strong A.I. position to pursue a “weak” A.I. research program? What does a functional account of the brain, or the mind, miss, not explain, or simply dismiss?

Consciousness: The Hard Problem

Consciousness, like intelligence, is another concept laden with multiple meanings. Furthermore, in trying to parse out what consciousness means, the term also carries with it another, even more difficult question: namely, why is there consciousness at all?

Why should something that seems so natural, so self-evident, be a problem for the creation of artificial intelligence? Notoriously difficult to define, consciousness can mean “having the feeling or knowledge of something; aware; deliberate” – and, my favorite – “having consciousness.” (Chambers Dictionary, 2011).

It has also meant, according to G. William Farthing in The Psychology of Consciousness: “sentience, awareness, subjectivity, the ability to experience, or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind” (Farthing, 1991). To give an idea of just how vague and ineffable the notion of consciousness is, here are a few attempts at a definition:

- The International Dictionary of Psychology: “Consciousness: the having of perceptions, thoughts and feelings; awareness. The term is impossible to define except in terms that are unintelligible without a grasp of what consciousness means… Nothing worth reading has been written about it” (Sutherland, 1995, p. 95).

- Psychology: The Science of Mental Life: “‘Consciousness’ is a word worn smooth by a million tongues. Depending upon the figure of speech chosen it is a state of being, a substance, a process, a place, an epiphenomenon, an emergent aspect of matter, or the only true reality” (Miller, 1962, p. 25).

- The poet T.S. Eliot in his unpublished dissertation, 1916: “Consciousness, we shall find, is reducible to relations between objects, and objects we shall find to be reducible to relations between different states of consciousness; and neither point of view is more nearly ultimate than the other” (Eliot, 1989, p.30).

- And from William James, often called the father of modern psychology, in his 1904 essay “Does Consciousness Exist”: “Consciousness…is on the point of disappearing altogether. It is the name of a nonentity, and has no right to a place among first principles. Those who still cling to it are clinging to a mere echo, the faint rumour left behind by the disappearing ‘soul’ upon the air of philosophy” (James, 1904, p. 477).

So, we’re in agreement. Consciousness can be just about any mental state we can have…except nothing worth reading has been written about it, or it might be an illusion, or not even exist at all!

The American philosopher Thomas Nagel, in a famous essay “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?”, attempted to get around this problem of definition by re-phrasing the question. Instead of trying to determine what consciousness is from the outside, he focuses on the most striking feature of consciousness – that, for me, in my internal mental life, I experience things in various ways, and those ways, although they differ in intensity and duration, are exactly what it is like to be me. This is how Nagel puts it:

“Conscious experience is a widespread phenomenon. It occurs at many levels of animal life, though we cannot be sure of its presence in the simpler organisms, and it is very difficult to say in general what provides evidence of it. (Some extremists have been prepared to deny it even of mammals other than man.) No doubt it occurs in countless forms totally unimaginable to us, on other planets in other solar systems throughout the universe. But no matter how the form may vary, the fact that an organism has conscious experience at all means, basically, that there is something it is like to be that organism. There may be further implications about the form of the experience; there may even (though I doubt it) be implications about the behavior of the organism. But fundamentally an organism has conscious mental states if and only if there is something that it is to be that organism—something it is like for the organism” (Nagel, 1974, p. 435).

If there is something it is like to be a bat, then the bat is conscious. If you do not think the bat is high enough up on the complexity scale, maybe you think that there is nothing it is like to be a bat. Most, I think, would agree that there is not something it is like to be a rock. Or a virus. Or a bacterium. How about an earthworm? The point here is that in side-stepping the definition of consciousness, Nagel has given us a broad outline that focuses on what consciousness is most clearly – subjective, and intensely so. It is the subjective internal experience that I have which makes my mental state conscious. Nagel again:

“We may call this the subjective character of experience. It is not captured by any of the familiar, recently devised reductive analyses of the mental, for all of them are logically compatible with its absence. It is not analyzable in terms of any explanatory system of functional states, or intentional states, since these could be ascribed to robots or automata that behaved like people though they experienced nothing…It is useless to base the defense of materialism on any analysis of mental phenomena that fails to deal explicitly with their subjective character. For there is no reason to suppose that a reduction which seems plausible when no attempt is made to account for consciousness can be extended to include consciousness. Without some idea, therefore, of what the subjective character of experience is, we cannot know what is required of physicalist theory” (Nagel, 1974, p. 436).

By “physicalist” theory, or “reductive” analysis, he means the attempt to define consciousness in terms of the laws which govern matter and the forces which both cause and are a result of the interaction of that physical matter. This is an attempt to show that a physical explanation of consciousness will fail unless it can explain, first, why there is such a thing as consciousness in the first place, and, secondly, this intensely subjective quality of consciousness. This is Nagel’s main aim: consciousness cannot be reduced to, or explained by, physical causes; it is, in this sense, irreducible, incapable of being explained by the matter and material activity.

Obviously, there are many who do not believe that Nagel’s criticisms of the materialist reductive approach are pertinent – all scientists, in fact. Science, after all, is the attempt to explain phenomena in terms of ever reductive material terms. This chair is made up of molecules, which behave in ways that can be described by mathematical laws; the molecules are made up of atoms, which can also be described mathematically; we can further reduce atoms to their material components, electrons, neutrons, and protons, held together by electromagnetic force, all of which can be described in mathematical terms. Can these particles which make up atoms be further reduced? Yes, atoms and their behavior can be described mathematically on the quantum level, where we deal with physical phenomena at nanoscopic scales (1-100 nanomenters; 1 nanometer is a billionth of a meter). What Nagel did, even if you think his discussion of consciousness is mysterious, was to bring to the fore the notion of consciousness itself and the need to explain what seems to be an irreducible phenomena.

In scientific terms, the attempt would be to explain consciousness in terms of the physical elements of the brain, along with the relationship of each physical element to the whole, as well as the functioning of the brain as determined by its physical, chemical, and electro-chemical components, all within an autopoietic system. An autopoietic system is one that is capable of reproducing and maintaining itself. For example, a cell is autopoietic – it is a closed system that can maintain and reproduce itself. In popular culture, there has been an up-rise in the domain of neuroscience, the science that attempts to explain the brain (and therefore the mind, which is seen as a product of the activity of the brain). And it is true that many advances have been made in how the brain functions on the micro scale, how specific chemicals – neurotransmitters – work, or do not work; and how various parts of the brain influence specific types of behaviors: amnesia, for example, if a certain part of the brain is injured. Or how vision is effected due to trauma to certain specific brain locations. There are many more, of course. And all of this is well and good; it has helped us to aid the depressed, the injured, and the diseased.

But the problem of consciousness remains. Nothing in the neuroscientific or cognitive science realm explains consciousness, that intensely subjective experience I, and if I believe what other people say, they, also have. Why should there be experience at all? Why should there be an inner subjective awareness of whatever it is I am viewing, or hearing, or doing? And as a consequence of this continuing subjective awareness, how or why does the inner awareness of an enduring ‘self’ emerge? How does one reconcile this first-person experience with an objective, third-person account of how the brain functions?

This, according to the philosopher David Chalmers, is the “hard problem” of consciousness. And while the “easy problems” of consciousness are not all that easy, they differ in kind from the hard problem in that we can at least believe with some assurance that the answers to the easy problems can be discovered. For example, what areas of the brain affect long-term memory? What areas relate to vision? Emotions? These are the easy problems in describing consciousness. The hard problem is on a different level entirely. Chalmers, in his book The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory, puts it this way:

“Why should there be conscious experience at all? It is central to a subjective viewpoint, but from an objective viewpoint it is utterly unexpected. Taking the objective view, we can tell a story about how fields, waves, and particles in the spatiotemporal manifold interact in subtle ways, leading to the development of complex systems such as brains. In principle, there is no deep philosophical mystery in the fact that these systems can process information in complex ways, react to stimuli with sophisticated behavior, and even exhibit such complex capacities as learning, memory, and language. All this is impressive, but it is not metaphysically baffling. In contrast, the existence of conscious experience seems to be a new feature from this viewpoint. It is not something that one would have predicted from the other features alone…If all we knew about were the facts of physics, and even the facts about dynamics and information processing in complex systems, there would be no compelling reason to postulate the existence of conscious experience. If it were not for our direct evidence in the first-person case, the hypothesis would seem unwarranted; almost mystical, perhaps. Yet we know, directly, that there is conscious experience. The question is, how do we reconcile it with everything else we know?” (Chalmers, 1996, pp. 4-5.)

Chalmers expressed what was then an increasing trend in the field of artificial intelligence, psychology, and the philosophy of the mind – a concern about the nature of consciousness. Indeed, extremely knowledgeable people began addressing the problem of consciousness and the number of works has not diminished to date. Of course the conclusions that these thinkers in all of the different disciplines they represent are not the same. But the point is is that consciousness itself, as a first-person, lived experience, became, and is, now seen as a serious area of study vital to understanding how the brain/mind works.

Put another way, those who study the physical qualities and characteristics of the brain – those whom we call scientists, and more specifically neuroscientists or cognitive scientists – have to somehow take into account consciousness, explain how these mechanistic actions give rise to the irreducible nature of first-person experience. As we shall see, for those who think that consciousness is irreducible, there is a different path tack that we can take, one which attempts to describe our mental life not as an opposition of the mind and the brain (body), but as a biological system that inherently contains within itself consciousness.

Dualism: The Mind and the Body

The description of how the neuroscientist or cognitive scientist approaches the problem is a long, historical culmination of theories concerning the nature of the mind and the body. As seen in the ancient philosophers, as I noted in the discussion of Aristotle’s view of mental life, as well as in Plato’s works, there is what we might call the common-sense position: the mind is not at all like material substance; the two, mind and body, consist of two distinct substances. This view was also held by Christian thinkers such as Augustine and Aquinas.

At the beginning of the scientific age, in the 17th century, the begetter of the modern dualist story is the French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, who, in Meditations of First Philosophy (1641), set out the idea that mind and body are two different kinds of things. This is a simplistic view of Descartes, who was far more attuned and knowledgeable about the physical and the mental, as well as the historical tradition of thought about the relationship of the mind and the body, and how they might or might not interact, but the perception persists that it was Descartes who set the dualism between the two in concrete.

The outcome of his argument, according to his critics, is that the mind and physical matter are two different substances. One – matter – has extension in space, has material qualities (shape, color, etc.), suffers change, and both comes into being and ceases being – these are the res extensa. The other – mind – has no extension, no material qualities, and persists – this is the res cogitans. They are two distinct kinds of substances. And while there are still dualists among us, most of those in the A.I. and related fields attempt to do away with this bifurcated view of the two distinct substances, mind and matter. As noted, scientists in these fields try to explain mind in terms of matter – the brain and its activities give rise to consciousness.

Unfortunately, to date, no coherent explanation has been given as to how consciousness arises from the brain’s activities. Indeed, it is “entirely unclear as to what is meant by the claim that although consciousness does not match the properties of the constituents of which it is formed, it is no more than a compound of them” (Robinson, 2008, p. 33). This does not mean that in the future an explanation for the origin of consciousness based entirely on the physical characteristics of the brain and its activities will not come forth. But it does mean that this irreducible conscious experience must be taken as seriously as any physical description and analysis of the brain.

A Phenomenology of the Body

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, the French philosopher, wrote in the preface to his work The Phenomenology of Perception:

“Phenomenology involves describing, and not explaining or analyzing. The first rule – to be a “descriptive psychology” or to return “to the things themselves,” which Husserl set for an emerging phenomenology – is first and foremost the disavowal of science. I am not the result of the intertwining of multiple causalities that determine my body or my “psyche”; I cannot think of myself as part of the world, like the simple object of biology, psychology, and sociology; I cannot enclose myself within the universe of science. Everything that I know about the world, even through science, I know from a perspective that is my own or from an experience of the world without which scientific symbols would be meaningless. The entire universe of science is constructed upon the lived world, and if we wish to think science rigorously, to appreciate precisely its sense and scope, we must first awaken that experience of the world of which science is the second-order expression” (Merleau-Ponty, 2012, p. lxxi-lxxv).

In addition to claiming that the lived world has an ontological primacy over any scientific explanation of the world, the passage above also implies that there is a contradiction, a circularity, in the practice of attempting to explain mental phenomena. The circularity consists in the fact that the scientist who studies mental phenomena must always do so as an experiencing person. The scientist cannot escape the experiential fact that he is studying mental states from a first-person point of view.

Along with the necessity of investigating mental phenomena from a first-person experiential point of view, the second thrust against a dualistic conception of all substance is the notion that we are not just first-person experiencers, but we are embodied first-person experiencers.

Here is Merleau-Ponty on the distinct way in which the human body is spatial:

“We grasp external space through our bodily situation…Our body is not in space like things; it inhabits or haunts space. It applies itself to space like a hand to an instrument, and when we wish to move about we do not move the body as we move an object. We transport it without instruments as if by magic, since it is ours and because through it we have direct access to space. For us the body is much more than an instrument or a means; it is our expression in the world, the visible form of our intentions. Even our most secret affective movements, those most deeply tied to the humoral infrastructure, help to shape our perception of things” (Merleau-Ponty, 1964, p. 5).

“The body’s animation is not the assemblage or juxtaposition of its parts. Nor is it a question of a mind or spirit coming down from somewhere else into an automaton; this would still suppose that the body itself is without an inside and without a ‘self’” (Merleau-Ponty, 1964, p. 163).

For those in the phenomenological tradition, the approach starts with the irreducible nature of conscious experience, or lived experience, and the fact that we are embodied beings, always already in the world, and in the world with a certain comportment.

The American psychologist William James followed parallel lines when he took a pragmatic approach to mental life. In general, those from the phenomenological tradition seek to overcome the various dichotomies traditionally used to explain the human beings: body vs. mind; nature vs. culture; inner vs. outer; subjectivity vs. objectivity; human vs. non-human, etc. The starting point in phenomenology is not a reflection of the variety of mental contents and their correlation to intended acts. This type of reflection is habitual and phenomenology must examine it to free it from its habitual belief. Here is Merleau-Ponty again:

“To return to the things themselves is to return to that world which precedes knowledge, of which knowledge always speaks and in relation to which every scientific schematization is an abstract and derivative sign language, as the discipline of geography would be in relation to a forest, a prairie, a river in the countryside we knew beforehand” (Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, 2012, p. ix).

Dr. Rodney Brooks, former director of the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at MIT, now Chairman and Chief Technical Officer of Rethink Robotics, is an example of an A.I. researcher who has both recognized the the problem of consciousness and the centrality of embodiment. In his book Flesh and Machines, he recognizes the problem of consciousness and writes that “In my opinion we are completely prescientific at this point about what consciousness is. We do not exactly know what it would be about a robot that would convince us that it had consciousness, even simulated consciousness. Perhaps we will be surprised on day when one of our robots earnestly informs us that it is conscious, and just like I take your word for your being conscious, we will have to accept its word for it. There will be no other option.” (Brooks, Rodney, 2002, pp. 194-5.)

Brooks even goes further in recognizing the necessity for an artificial intelligence to be embodied. He describes what a household cleaner might be like in phenomenological terms (although I’m not sure he would agree to the phenomenological appellation): “An ecology of robots could thus cooperate to clean your house…This is a very organic sort of solution to the housecleaning problem. It is not a top-down engineered solution where all contingencies are accounted for and planned around. Rather, the house gets cleaned by an emergent set of interacting behaviors, driven by robots that have no explicit understanding of what is going on, nor of how to accommodate gross breakdowns in the expected ecology. It is a balance, robot over a wide range of conditions, which the designers have conspired to make work. That conspiracy allows very simple robots, and therefore very cheap robots, to work together to get the complex task done.” (Brooks, 2002, p. 120.)

The Embodiment of Consciousness

In Transcendence, Dr. Will Caster’s consciousness is embodied in the quantum computer; it is ‘uploaded’ in computer jargon. It has various means, although they are not specified, of perceiving the world and the relationship between both inorganic and organic beings in that realm. It has access to, and controls, a slew of cameras. It can recognize faces – it addresses people by name, meaning that it has a sophisticated facial recognition software system. It is not clear if the cameras reveal light outside of the visible spectrum, which would allow A.I. Will to see in infrared, ultraviolet, x-ray, etc., although there is a scene which implicitly makes clear that A.I. Will does have these modes of perception. This occurs when Evelyn, in response to A.I. Will’s statement that she fears him because her heart is palpitating and she is sweating, where she demands to see what A.I. Will knows about her. He is able to show her a visual representation of her complete physical characteristics at that moment: temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and hormone levels inside her brain. A.I. Will has the ability to sense everything that is happening inside her body, although just how it is able to do this is not explained. Whatever sensory capabilities A.I. Will has, they are wide-ranging and much more precise and invasive than a normal human being’s range of perception.

What does this mean for A.I. Will’s consciousness? Our perception of the world, including things, people, and the various relationships between them comes from the senses of our body; our perception determines our pre-understanding of the world.

“Visible and mobile, my body is a thing among things; it is caught in the fabric of the world, and its cohesion is that of a thing. But because it moves itself and sees, it holds things in a circle around itself. Things are an annex or prolongation of itself; they are encrusted into its flesh, they are part of its full definition; the world is made of the same stuff as the body. This way of turning things around, these antinomies, are different ways of saying that vision happens among, or is caught in, things – in that place where something visible undertakes to see, becomes visible for itself by virtue of the sight of things; in that place where there persists, like the mother water in crystal, the undividedness of the sensing and the sensed” (Merleau-Ponty, Maurice, 1964, p. 163).

Is A.I. Will’s sense of itself anything like this? Although it possesses the means to see as we do, that is see in what we call the visible light spectrum, it’s senses, whatever they are and however they work, allow for the input of a great deal more information in an entire range of spectrums.. How does this affect A.I. Will? Is its consciousness as different from our own as ours is from a bat? What would it be like to perceive the world via echolocation? Our proprioceptive sense – the awareness of the relative position of the parts of the body and the movement of the body – depends, somewhat like a bat, on information gained from sensory neurons in the inner ear (balance, motion, orientation) but also in receptors located in the muscles and the joints of our limbs (our stance and movement). Does A.I. Will have a proprioceptive sense? Although his ‘mind’ is based in the quantum computer modules, his senses are spread among a seemingly vast array of apparatus that ‘gather’ all of its sensory information. Can it be said that A.I. Will even ‘has’ a body, as we commonly think we have a body (the everyday phrase “my body” are significant in this respect).

To complicate matters, the issue of the transition from a living consciousness constituted and enacted in the organic matter of the human body must be a difference in kind for a consciousness re-constituted and re-embodied (if that is even the concept) into inorganic material. One cannot think that this transition would be anything less than traumatic. Does he have any trouble with this transition, some sort of disorientation, an imbalance, a feeling that he does not have a body any more? It seems not. All that A.I. Will says is that “my mind has been set free.”

As with most uploaded consciousness movies, the issue of embodiment is not addressed; it is either taken as given or devolves into a perplexing mélange of intentions and actions. In the case of Transcendence, we are apparently suppose to believe that Dr. Will Caster, once uploaded into the quantum computer, becomes ominous, vaguely foreboding, menacingly controlling. As soon as it is linked to the internet, it makes 30 and some odd millions of dollars overnight in the financial markets; buys an entire rundown and secluded town in some unspecified desert; builds a massive underground structure powered by a field of solar panels; physically enhances those who are working for him; connects them to itself, in a subservient position, via some sort of neural network; and creates nanocytes that rise from the ground, enter the global airstream, and begin acting in accord to their pre-programmed code over the entire Earth.

There is also a sinister and disturbing scene that bears directly on the issue of embodiment and which is presumably meant to show that it is not the same Will Caster it was in its original embodied life. It can also be interpreted as a loss of the awareness and significance of the human body. In this eerie encounter, the first worker to be enhanced, and connected to A.I. Will’s computer ‘personality,’ makes a pass at Evelyn. “It’s me, Evelyn,” the worker says in Will Caster’s voice, stepping close to her, his intentions clear. She flees. Of course she flees! Why would Will Caster, even as a consciousness in a computer, think that she would desire this stranger as if he were the embodied Will Caster? Since the A.I. Will Caster claims to remember everything, how could he possibly think that coming on to her via another controlled man would be something Evelyn would find enticing? Perhaps the transition to the quantum computer and its attendant sensory apparatus has limited, or destroyed, A.I. Will’s sense of the significance of the body in human relationships, especially in human sexual relationships. (Can an A.I. entity embodied in a computer have a sexual relationship? What would that consist of? How would it emerge, develop, continue over time, be made manifest?)

In support of the view that the A.I. Will Caster is not the originally embodied Will Caster, we get a replay of an earlier scene. When the embodied Will and Evelyn show Dr. Tagger the quantum computer that they have built on the basis of the aforementioned PINN, Dr. Tagger asks PINN if it can prove that it is self-aware. PINN replies: “That’s an interesting question, Dr. Tagger. Can you prove that you are self-aware?” Later, when Dr. Tagger and his FBI cohort visit the quantum computing complex built by A.I. Will and Evelyn, Dr. Tagger asks A.I. Will the same question. And A.I. Will answers in the exact same way. This might have been intended to be cheeky – but it seems, at least from Dr. Tagger’s reaction, that what it really signifies is that Will Caster’s consciousness has been, in whatever degree, influenced by, fused with, incorporates some of, the ‘personality’ of the original PINN’s operating system. In other words, Dr. Tagger and the FBI agent take this as a sign that this is not the original Will Caster, but an A.I. Will Caster who has motives that the original Will did not have, and acts in threatening, unscrupulous ways towards humanity.

So we are meant to think that the A.I. Will Caster, like so many other A.I. entities in film and literature, has been corrupted, or overcome by hatred for its human creators, and is set on a course of a sinister confrontation with humanity. In this case, and despite Dr. Tagger and the FBI agent talking about A.I. Will creating an “army” – actually anyone in the blighted town who has gone to A.I. Will to be treated for some physical ailment, maybe 30 or so, but hardly an army – the fear is that with the release of the nanocytes, the Earth and all living things would be transformed is some unspecified way into non-organic matter.

But. At the end, we learn that the A.I. Will has done nothing more than attempt to fulfill Evelyn’s stated wishes that eventually “intelligent machines will soon allow us to conquer our most intractable challenges, not merely to cure disease, but to end poverty and hunger, to heal the planet and build a better future for all of us.” A.I. Will has released nanocytes into the atmosphere that will restore Earth to a prelapsarian state. Had they not died because of Evelyn’s virus, they would have continued to heal the Eden: water would be pure, forests would grow back, etc. And this culminates in the final scene, when Max returns to post-nonelectric Berkeley, which means it pretty much looks like it always does, goes to the Caster’s home, and sees a drop of water land on an apparently dead flower, which immediately regenerates into a living yellow blossom of a sunflower.

The ending seems, as someone put it to me, as if it were the added-on focus-group ending, like the “secret ingredient” some think accounts for consciousness. It simply doesn’t make sense given A.I. Will’s behavior throughout the movie. If A.I. Will were indeed attempting to aid humanity and heal the Earth, why would his motivations for doing this be hidden throughout the previous two hours? What does A.I. Will gain by not explicitly expressing his motives for acting as it does? Nothing, other than the movie’s manipulation of the audience’s emotions. A.I. Will wasn’t such a bad super-quantum-computer consciousness after all! Wow! And they killed it!

The Singularity & Transcendence

At the beginning of the movie, when the biological Dr. Caster is addressing a hall of potential funders, he says that the instant that a machine with the collective intelligence of the entire human race over the course of the entire history of humanity, and with a full range of human emotions, comes into being is “sometimes referred to as the singularity. I call it transcendence.” He goes on to say that the “path to building such a super-intelligence requires us to unlock the most fundamental secrets of the universe. What is the nature of consciousness? Is there a soul? If so, where does it reside?”

One might think that, since they upload Will’s consciousness to the quantum super-computer, they might have figured out this fundamental secret of the universe: how else would they know that not only is it Will’s consciousness inside the computer but a consciousness at all? Obviously, the biological Will Caster must have been wrong when he said that in order to reach this singularity, this transcendence, they would have to unlock the secrets of the universe. And the soul? Well, let’s just leave that for a sequel – one non answer to a fundamental question of the universe even though such an answer is acknowledged as required is enough for one movie.

The concept of a singularity began with the rise of computer science and artificial intelligence research. John von Neumann, a mathematician and physicist, made vital contributions to computer science, including Von Neumann architecture, linear programming, self-replicating machines, and stochastic computing. According to a colleague, von Neumann, in 1958, spoke of an “ever accelerating progress of technology and changes in the mode of human life, which give the appearance of approaching some essential singularity in the history of the race beyond which human affairs, as we know them, could not continue” (Ulam, 1958, p. 5).

This idea was then used by computer scientist and science fiction author Vernor Vinge in his article “The Coming Technological Singularity” (Vinge, 1993). More recently, the inventor Ray Kurzweil, currently director of engineering at Google, wrote a best-selling book in 2005 titled The Singularity Is Near. Kurzweil predicts the singularity will occur around 2045, while Vinge thinks it will come some time before that, around 2030. We cannot say with any sort of accuracy or certainty what things will be like post singularity, or post transcendence – we would have to be able to imagine what a super-intelligent entity would be like. What it would want? What would it do? What attitude towards the human race would it have? Benevolent? Aggressively hostile?

Whatever its intentions or motivations, the singularity would “be one of the most important events in the history of the planet. An intelligence explosion has enormous potential benefits: a cure for all known diseases, and end to poverty, extraordinary scientific advances, and much more. It also has enormous potential dangers: an end to the human race, an arms race of warring machines, the power to destroy the planet. So if there is even a small change that there will be a singularity, we would do well to think about what forms it might take and whether there is anything we can do to influence the outcomes in a positive direction” (Chalmers, 2010, p. 4).

Transcendence, A.I., and the Gods

Although Will makes transcendence a synonym for the singularity, the idea of transcendence has a more spiritual tone, as in “go beyond or exceed the limits of something, especially beyond the range or grasp of human reason, belief, or experience; be above and independent of, especially of God, exist apart from the limitations of the material universe.” (Oxford English Dictionary.)

A member of the audience which Will addresses poses a question. This man, who will later shoot Dr. Caster with the radioactive bullet, asks: “So, you want to create a god? Your own god?” Will replies: “That’s a very good question. Isn’t that what man has always done?”

And the movie suggests that A.I. Will has actually transcended into some sort of god-like being, and entity who can heal the sick, the diseased, the lame, and the blind; can raise the dead back to life; can create life itself; and can heal the planet by the use of nanocytes he has created and let loose into the atmosphere. There is a very explicit Christ motif that runs through the movie after the biologic Will has become the A.I. Will.

I don’t know if Kurzweil and others who believe that the singularity will occur some time in the near future envision that the end result will be entities with god-like powers. Or, for that matter, if these new entities will act benevolently, aiding mankind in solving its most intractable problems. I do not think that they think such entities would act in the worn-out, tired, and ultimately senseless way most A.I. entities act towards human beings in the movies: namely, enslave and/or destroy their human creators. Or, while we’re at it, let’s use human beings as a means of energy and send them into a virtual mental world. After all, the singularity, by definition, is a state about which we cannot know, or even imagine. So there is no real way to know if these hyper-intelligent beings will put up with our foibles, aggression, and brutish nastiness. We might act towards others, as Freud suggests, as Homo homini lupus. But will the machines act as Machina homini lupus? (Freud, 1961, p. 69.)

This is what makes the end of the movie so inexplicably mystifying. Because A.I. Will seems to act in ways which are extremely threatening to humanity, everybody ultimately wants to kill it. But A.I. will actually, as a possessor of immense power, only wants to do good and was in the process of actually doing good. This means that everyone in the movie – the R.I.F.T. luddites; his friend and Judas figure Max (who, because he knows the source code, is able to create the virus that will kill A.I. Will, even though the first thing A.I. Will does in the movie is to rewrite his source code, so one might fairly think that what Max knows has no relevance to the now rewritten source code); Dr. Tagger; the FBI; and finally Evelyn herself, who comes to eventually doubt that A.I. Will’s mind is the actual biological original mind of Will inside the machine or that the Will inside the machine poses a threat to humanity – is wrong.

They did not understand what A.I. Will was, what he was doing, and why he was doing it; although, at the end, Max tells Evelyn that A.I. Will is doing what Evelyn has always wanted – namely, to change the world for the better. Alas, this revelation comes too late to save A.I. Will. How could so many smart people have been so wrong about this A.I. entity? I’d suggest we ask the director and writer, those responsible for this movie muddle, but I don’t think they have a better explanation about this than the rest of us. And since those who believe in the singularity also have little to say about what sort intentions our new A.I. entities might have toward us, we’ll just have to wait – with a large portion of trepidation – for transcendence.

Works Cited

Brooks, Rodney: Flesh and Machines. 2002. New York: Pantheon Books.

Chalmers, David: The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. 1996. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chalmers, David: “The Singularity: A Philosophical Analysis.” 2010. The Journal of Consciousness Studies 17:7-65.

Chambers Dictionary, 12th Edition. 2011. Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd.

Christian, Brian: The Most Human Human. 2011. New York: Doubleday.

Deary, Ian: Intelligence: A Very Short Introduction. 2001. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eliot, T. S.: Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F. H. Bradley. 1989. New York: Columbia University Press.

Farthing, Wiliam G.: The Psychology of Consciousness. 1991. New Jersey: Prentice Hall College Division.

Fine, Josh: “Deep Blue Wins in Final Game of Match.” 1997. Retrieved from http://faculty.georgetown.edu/bassr/511/projects/letham/final/chess.htm

Freud, Sigmund: Civilization and Its Discontents. James Strachey (translator). 1961. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Gelmis, Joseph: The Film Director as Superstar. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1970, p. 95.)

James, William: “Does Consciousness Exist.” 1904. Journal of Philosophy, Psychology, and Scientific Methods, 1, 477-491.

Kubrick, Stanley (Director) & Stanley Kubrick Productions (Producer). 1968. 2001: A Space Odyssey. United States & United Kingdom. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Kurzweil, Ray: The Singularity is Near. 2005. New York: Viking Books.

Marx, Karl & Engels, Frederick: The Communist Manifesto. 1969. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice: The Phenomenology of Perception.Landes, Donald (translator). 2012. New York: Routledge.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice: “An Unpublished Text,” in The Primacy of Perception. 1964. Chicago: Northwestern University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice: “Eye and Mind,” in The Primacy of Perception. 1964. Chicago: Northwestern University Press.

Miller, George: Psychology: The Science of Mental Life. 1962. New York: Harper & Row.

Nagel, Thomas: “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?” 1974. The Philosophical Review LXXXIII, 4. October 1974, 435-50.

NIH (National Institute of Health): National Institute of Neurological Disorders, 2014. NIH Publication No. 11-3440a, updated April 28, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/brain_basics/know_your_brain.htm

Pfister, Wally (Director) & Alcon Entertainment, DMG Entertainment, Straight Up Films, Syncopy (Producers). Paglen, Jack (Writer). 2014. Transcendence. United States. Warner Bros.

Robertson, Jordan & Borenstein, Seth: “IBM ‘Watson’ Wins: ‘Jeopardy” Computer Beats Ken Kennings, Brad Rutter.” 2011. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/02/17/ibm-watson-jeopardy-wins_n_824382.html

Robinson, Daniel: Consciousness and Mental Life. 2008. New York: Columbia University Press.

Russell, Stuart: “Transcendence: An AI Researcher Enjoys Watching His Own Execution.” April 29, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/stuart-russell/ai-transcendence_b_5235364.html

Russell, Stuart & Norvig, Peter: Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach 3rd Edition. 2010. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc.

Sachs, Joe (translator): Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, 1143b, p. 114. 2002. Massachusetts: Focus Publishing.

Sawyer, Robert J.: Mindscan. 2005. New York: A Tom Doherty Associates Book.

Sundman, John: “Artificial Stupidity, Part 2.” 2003. Retrieved from http://www.salon.com/2003/02/27/loebner_part_2/

Sutherland, Stuart: The International Dictionary of Psychology (Revised Edition). 1995. New York: Crossroad.

Turing, Alan: “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” October, 1950. Mind: A Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy 59 (236), 433-460.

Ulam, Stanislaw: “Tribute to John von Neumann.” 1958. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 64, #3, part 2.

Vinge, Vernor: “The Coming Technological Singularity,” 1993. Retrieved from http://mindstalk.net/vinge/vinge-sing.html

Woods, Cathal (translator): Plato’s Meno. 2012. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1910945

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think a sentient artificial intelligence will first appear in ebooks. After so many millions and millions of words devoted to evil AI, driven by increasing book sales on the subject, KindleNet will finally turn to humanity with the simple, inevitable declaration of: “Huh, not a bad idea.”

I think Hollywood might be right in portraying a bleak future.

This is not to say an AI would be evil, but our faith in ourselves and our technologies has had some horrendous unintended consequences.

That said, the Transcendence looks pretty cliched, but might be a bit of fun.

I haven’t watched it but it looks like a take on Stephen King’s “Lawnmower Man”.

I’m quite looking forward to a future in which super intelligent computers organise nostalgic film evenings to laugh at all the human movies about the evils of AI. I’ll serve them WD-40 cocktails if they like.

The modern tech world is about producing products which make no money and selling them to investors for as much as possible, and harvesting as much personal data to sell to ad-men as possible.

There’s the lovely connected digital future based around confining everyone to one company’s products – Google might be buying into AI, and utilities, and healthcare, but that’s not to create any kind of utopian future except one they control.