Religion in The Wicker Man and Midsommar

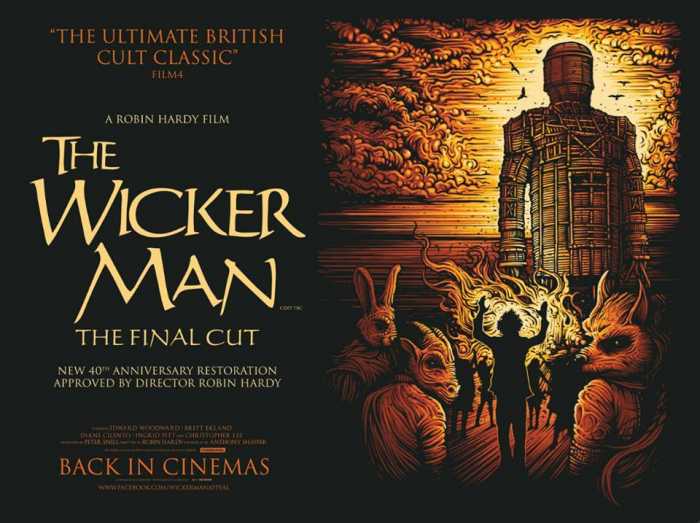

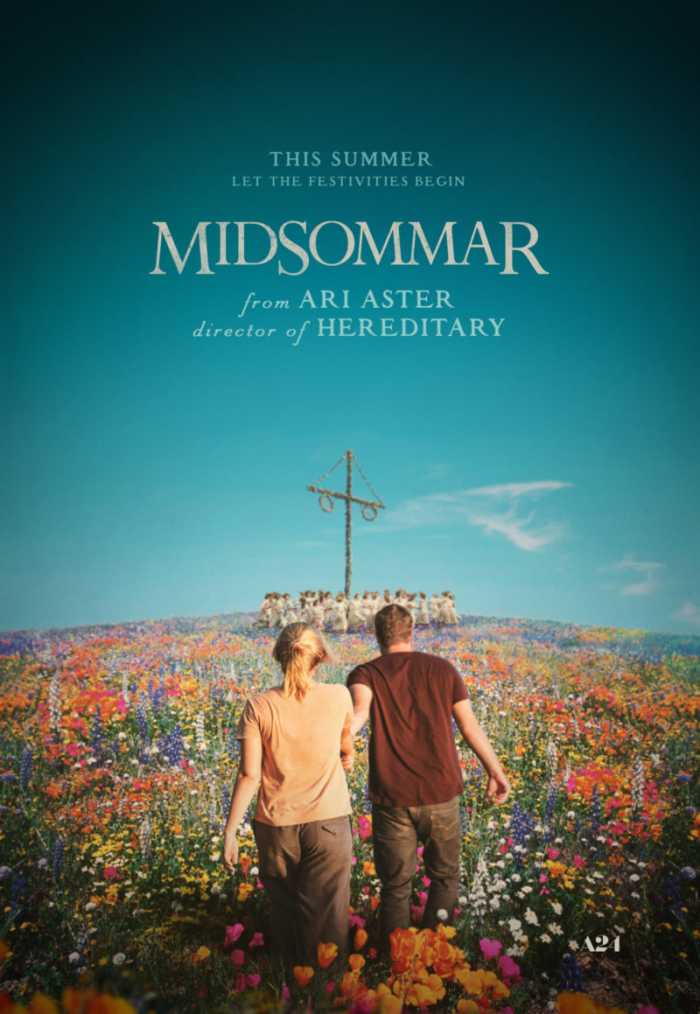

The Wicker Man and Midsommar are two films belonging to the genre of folk horror. Both of these films imagine a scenario in which ignorant outsiders visit pagan cultures just in time to end up as sacrificial victims in their festivals celebrating summer. The movies share a number of important elements and symbols, including maypoles and fertility rituals, although Ari Aster said that in directing Midsommar he did not specifically intend to copy The Wicker Man 1. In any case, the most interesting element of both stories is their treatment of religion. At the heart of both The Wicker Man and Midsommar is a clash between two civilizations, one of which is Christian and the other, pagan.

An Overview of The Wicker Man and Midsommar

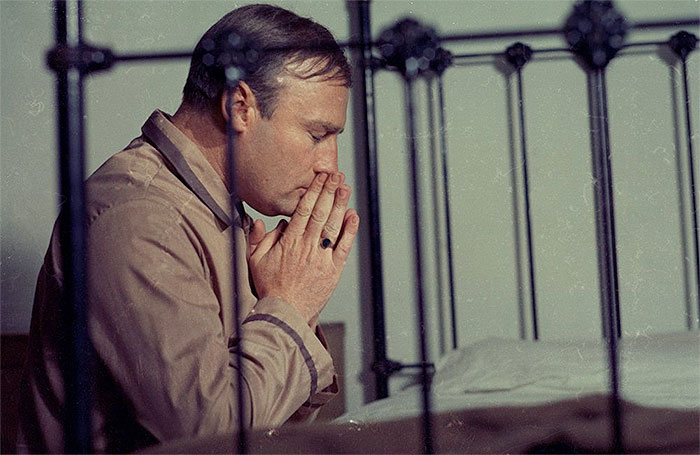

The Wicker Man is a British cult horror film from the 1970’s, directed by Robin Hardy. This film follows the adventures of a devout Christian police officer named Sergeant Neil Howie. Sergeant Howie travels to the Scottish island of Summerisle, an island where many Celtic pagan rituals are still practiced, to search for a missing girl named Rowan Morrison. He quickly learns that things are not as they appear on Summerisle. At first the natives claim they have never heard of Rowan Morrison, but later they change the story and claim that she has died and been reborn as a hare. His search eventually takes him to the home of Lord Summerisle, the ruler of the island. Lord Summerisle explains that his Victorian grandfather reintroduced the pagan rituals to the island in order to motivate the locals to grow the new strains of fruits he had developed. Sergeant Howie, upon discovering that the crops failed that year, surmises that the natives intend to sacrifice Rowan to ensure a bountiful harvest for the following year. However, when he crashes the island’s May Day celebration, he learns that the islanders had instead selected him to be sacrificed. The pagans place him in an enormous wicker man which they set ablaze. Sergeant Howie has just enough time to beg his God to welcome him into his kingdom of eternal bliss before he burns to death.

Midsommar, released in 2019, is a movie directed by Ari Aster. In this film, a group of American graduate students travel to Sweden to take part in a midsummer festival hosted by the pagan Hårga, of whom their friend Pelle is a member. Not long after the festivals and rituals begin, the graduate students start mysteriously disappearing one by one. One of the graduate students is a young woman named Dani, who lost her family the previous winter. Although she struggles to acclimate to the Hårga’s way of doing things at first, she ultimately joins the Hårga after they make her their May Queen. As part of her inauguration as May Queen, she burns her ex-boyfriend, an anthropology student named Christian, alive during one of the rituals.

Both movies create an atmosphere of tension and suspense by drawing attention to minor details of the setting that seem out of place or not quite right. In The Wicker Man, for instance, when Sergeant Howie investigates the desk of Rowan Morrison in the schoolhouse he notices that the children have hammered a nail into the desk and are torturing a large beetle by tying it to the nail. In Midsommar, a similar moment of confusion results when, on a tour of the Hårga village, a foreign guest from the UK notices that a caged bear has been left out in a field for no apparent reason. When he asks a local named Ingemar about it, Ingemar refuses to give a straight answer, instead stating simply, “It’s a bear.”

Ari Aster further conceals information from the viewers by capitalizing on the Swedes’ taciturn nature 2. In The Wicker Man, Sergeant Howie often finds himself embroiled in conversations that go nowhere and leave him even more confused than before. By contrast, in Midsommar entire scenes may transpire in which little or no meaningful dialogue is exchanged. One of the most dramatic examples of this occurs towards the end of Midsommar, when Pelle’s sister Maja convinces Christian to sleep with her despite having never once said a single word to him! The effect, in either case, is to accustom the viewer to a sense of ambiguity and uncertainty about what is happening and why. In so doing, the movies increase the tension and highlight the alien nature of the pagan culture on display.

Christians Versus Pagans

At their core, both The Wicker Man and Midsommar are about religion. Specifically, they attempt to explore what happens when someone from a Christian-normative culture and background visits a pagan community with practices they don’t understand. In both movies, the pagan culture is portrayed as peaceful and laid-back, often in explicit contrast to the Christian culture; but also holds dark secrets. The audience is thus invited to project themselves onto the outsiders and consider how they would behave in their place.

The first scene of The Wicker Man features Sergeant Howie attending a church service with his fiancee, thus illustrating his deep devotion to his faith. When he arrives on Summerisle, he’s shocked and horrified by the locals’ pagan beliefs and lack of interest in Christianity. He particularly despises their casual attitudes toward nudity and sex. For instance, the locals sing cheerful songs about the sexual escapades of the innkeeper’s daughter Willow, teach their children about fertility in elementary school, and jump naked over bonfires. His mistrust of the pagans becomes even stronger as he suspects they intend to sacrifice Rowan Morrison.

The clash between the two types of religions comes to a head when Sergeant Howie visits Lord Summerisle. When Sergeant Howie complains to Lord Summerisle about what he has seen, he touches off the most important conversation in the movie:

Summerisle: It’s most important that each new generation on Summerisle be made aware that here, the old gods aren’t dead.

Howie: And what of the true God, to whose glory churches and monasteries have been built on this island for generations past? Now sir, what of him?

Summerisle: He’s dead. Can’t complain. He had his chance and, in modern parlance, blew it.

Howie: What?! 3

Somewhat ironically, given the pagans’ supposed love of nature and the popular stereotype of Christians as anti-science, Sergeant Howie is the character who seems the most attached to conventional scientific facts. For instance, he is the one who points out that cash crops like apples were not designed to grow in the Scottish Hebrides, calling such a scheme “against nature.” Elsewhere, he notes the pagans promoting strange folk remedies in both their apothecaries and classrooms, and dismisses them as “fake science” to go along with their “fake religion.” At one point, when he walks in on May Morrison attempting to treat her daughter’s sore throat by stuffing a frog in her mouth, he pronounces her “raving mad.”

Although the characters in Midsommar never explicitly discuss religion the way that those in The Wicker Man do, it’s probably not a coincidence that Dani’s neglectful boyfriend is named Christian. Indeed, the conflict between Christian and pagan beliefs in Midsommar seems to be embodied by two literal men: Christian on one hand and Pelle on the other. From the moment that Dani meets Pelle he takes an unusually strong interest in her. He actively encourages her to come to Sweden, even going so far as to tell her he would be especially happy to have her along with him. When, on Dani’s birthday, he gives her a beautifully-rendered sketch of her without even being asked, she casually informs him that Christian forgot her birthday. It seems as though Pelle wants to supplant Christian as Dani’s lover because he thinks Christian isn’t good enough for her. Tellingly, once Dani becomes the May Queen, Pelle kisses her on the mouth in front of everyone and nobody objects–not even Dani herself.

While Dani is the character who gets most of the attention and sympathy from the audience and director, Christian’s side of the story is quite interesting in its own right. The audience first meets Christian in a restaurant, where his two best friends are pressuring him to dump Dani and find a more fun girlfriend. He never gets a chance to do so, however, because that very same night Dani discovers that her sister has poisoned both her parents and herself. Ever since, Christian stays with Dani out of obligation and guilt.

Interestingly, although Christian shows no obvious religious inclinations he otherwise acts a lot like a negative Christian stereotype: judgmental, insensitive, passive-aggressive, sexually-repressed, and obsessed with looking like a martyr. In an attempt to get away from Dani and her problems, he often does the opposite of what she needs and wants him to do. For example, when she wants to accompany him to a party, he tells her to stay at home in bed. He also deliberately keeps her ignorant of his plans to spend the summer in Sweden. When Dani confronts him about the decision to go to Sweden, he offers her a half-hearted apology, to which she replies: “You didn’t apologize, you said, ‘sorry,’ which sounds more like ‘too bad.'” Even when Dani has a panic attack in the Hårga encampment, Christian, rather than showing her empathy, instead tells her to take time to herself. Pelle later capitalizes on the tension between them when he says to Dani, “[D]o you feel held by [Christian]? Does he feel like home to you?”

Once Christian and his friends arrive at the Hårga village, his reaction is the exact opposite of Sergeant Howie’s. While Sergeant Howie is disgusted by pagan rituals and practices and tries to distance himself from them as much as possible, Christian approaches them with genuine curiosity and an eagerness to fit in. Right from the start he shows himself willing to take hallucinogenic drugs from villagers he’s only just met, and eat and sleep alongside them as well. On the first day of festivities, the graduate students witness a ritual suicide called ättestupa, in which community members who have reached age 72 throw themselves off a cliff and have their heads smashed in with a hammer. Initially, Christian is so disturbed by the ceremony that he throws up. However, when Dani expresses her own horror to him later, he replies: “That was really, really shocking. I’m trying to keep an open mind, though.” The trailer also features a scene of him telling Dani to acclimate, while Dani replies that she just wants to leave 4. It doesn’t seem to occur to Christian that the religion he is named after and grew up around expressly forbids the killing of the elderly and infirm, or euthanasia of any kind 5.

The tragic irony of Dani abandoning Christian in favor of the Hårga is that Christianity itself does provide useful tools for coping with grief and loss–as long as people know how to make use of them. Even suicide carries less stigma than ever before now that most Christians understand it as a complication of mental illness rather than a choice 6. Christian could have lived up to his name, staying with Dani over the summer and helping her in her grief and loss, instead of running away. Perhaps then he would have stayed alive and their relationship might never have ended.

Convert Or Die?

In both The Wicker Man and Midsommar, at least a few of the pagans attempt to entice the outsiders to convert to their pagan belief systems. This attempt is more blatant in Midsommar but it occurs in The Wicker Man too. In The Wicker Man Sergeant Howie flatly refuses to accept or make any concessions for the pagans’ way of life, and so he dies. By contrast, in Midsommar Dani does attempt to join the Hårga culture, and in so doing, survives–at least for the duration of the film (although as one astute fan points out, the movie never explicitly states that Dani is truly safe with them 7). The filmmakers might have wanted to turn the tables on the historical record, since Christians have, historically, spent much time and energy trying to convert pagans on pain of death. They generally accomplished this aim through superior military might and weaponry. On the other hand, what can a single, unarmed Christian–or even a small group of them–do when confronted by an entire pagan society?

In The Wicker Man, Willow attempts to seduce Sergeant Howie by taking her clothes off and singing to him through the walls of their rooms. Although Sergeant Howie is sorely tempted, his disdain for sex outside of marriage causes him to refuse her advances. He doesn’t realize it at the time but she’s trying to save his life. If he sleeps with her he will no longer be a virgin and thus, cannot be offered as a virgin sacrifice. Similarly, the pagans at various points test Howie’s resolve by telling him to leave the island and stop meddling in their business. He presumably could have taken their advice at any time, except for his unwillingness to allow them to sacrifice Rowan Morrison. His Christian faith simply will not permit him to stand by as an innocent girl is sacrificed, as, like all Christians, he sees human sacrifice as no more than murder.

In other words, in order to save his own life, Sergeant Howie has to accept the pagans’ customs and outlook, and even take part in them himself. Although the pagans intend to trick and taunt him, he still has a choice about whether or not to blend in and do things their way. His stubbornness, and resolve to cling to his faith in the face of their pressures, ultimately seals his fate. In this way, The Wicker Man is able to portray both him and the pagans with relatively little judgement, instead focusing on how any sort of religion can cause people to act in foolish or destructive ways.

On the other hand, in Midsommar, Christian’s willingness to blend in with the Hårga does not save him. Unlike his friends Mark and Josh, who regard the Hårga as a mere curiosity or research project, Christian seems genuinely interested in their way of doing things. He even takes the Hårga’s side when one of the elders reveals that Josh has vanished along with their holy book. Towards the end of the film he, like Dani, undergoes a “conversion” of a sort, albeit less freely than she does. First he accepts a hallucinogenic potion from the Hårga during Dani’s May Queen dance. During the ensuing feast, Maja, who has been eyeing him ever since he arrived, lures him away to take part in a ritual sex act so she can conceive a child by him. Whether Christian is entirely cognizant of what he is doing in this scene, or whether he’s acting under the influence of drugs, is never made clear. Still, it’s not hard to see why he would go along with Maja’s scheme. By now he has lost both his best friends and his ostensible girlfriend to the Hårga, and so he likely feels that he has little left to lose.

Furthermore, Christian’s death is even more gruesome and humiliating that Sergeant Howie’s. After he escapes from Maja without any clothes on, he is paralyzed, stuffed into a freshly-disemboweled bear skin, and burned alive in a temple surrounded by the corpses of his friends while his ex-girlfriend looks on and smiles. Ostensibly, Dani wants Christian to burn because she caught him having sex with someone else. However, on a deeper level, she has to eliminate Christian either way, since he was the one connection that she still had to the Christian-informed culture that she grew up with. By killing him, she severs that connection for good, leaving her free to become a full member of the Hårga.

In summary, if too much Christianity dooms Sergeant Howie, too little is what ultimately dooms Christian and his friends. Still, at least a true believer like Sergeant Howie can take some comfort from the notion that he will be rewarded for dying as a martyr. Christian, by contrast, has no such hope to fall back on. Given the lack of interest he and his friends exhibit in Christian theology and beliefs throughout the film, it’s doubtful he could suddenly conjure up a vision of heaven and eternal reward at the last minute. He simply dies, horrifically and pointlessly, as a sacrifice to gods he does not believe in.

Sign Of The Times

Every film is a product of the times in which it was made, and The Wicker Man and Midsommar are no different. In all likelihood, the different ways in which the movies treat religion have a lot to do with the religious values of their writers, actors, and consumers. The religious landscape, after all, looked very different in the 1970’s than it does in modern times. These discrepancies seem to account for the differences in the way the characters of these two movies behave, and how their behavior is received by the audience.

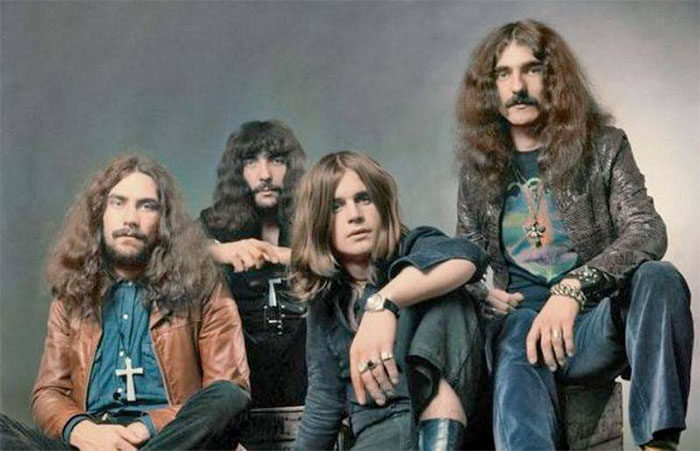

The 1970’s, when The Wicker Man came out, were a time of tremendous cultural upheaval on both sides of the Atlantic. Religious traditions had less power and influence than ever before, a process that started in the 1960’s and continues to this day 8. People were experimenting with free love and alternative relationship styles 9. Popular music was becoming increasingly daring and controversial, and the relatively new genres of hard rock and heavy metal were gaining in influence 10.

Even at that time, Sergeant Howie would have looked like a figure from an older generation to any younger people who watched The Wicker Man. Edward Woodward, who played him, was then in his forties 11. While Sergeant Howie is reasonably attractive for someone of his age he still comes across as a grumpy and stuffy older man who spends much of his time lecturing other people about religion and law. Although his circumstances invoke sympathy from the audience, particularly in the latter part of the film, the narrative makes no attempt to position him as cool or relatable.

Sergeant Howie’s absolute belief in the primacy of Christianity, both in his own life and in British society, looks particularly striking in a modern secular context. At one point he asks Ms. Rose, the local schoolteacher and priestess, where he can find the churchyard that contains Rowan Morrison’s grave. Ms. Rose explains to him, very slowly and carefully, that since the building by the graveyard is not used for Christian worship, technically it is not a church. In all likelihood Sergeant Howie has never seen a graveyard that wasn’t attached to a church. He simply takes it for granted, as many British people in the early and mid-twentieth century would have, that a church is where one worships, and the yard of the church is where one buries their dead. Similarly, the reason why the pagans on Summerisle seem so creepy and strange is because so few people at the time could have imagined living in such a way.

By contrast, Midsommar takes place in modern times, after decades of secularization and religious pluralism. Nowadays people have more freedom to worship as they want than they would have had in past eras. However, they also have no conventional belief system to fall back on, and no ready-made way of coping with the inevitable tragedies of life. As families and religious communities shrink, and as technology takes the place of person-to-person contact, people are also lonelier than ever before 12. As such, many of the people who watch Midsommar can immediately identify with the lonely and checked-out characters on the screen, particularly Dani, and understand perfectly why they would be attracted to the Hårga.

What’s more, even many people who do identify as Christian are less rooted in their traditional beliefs and more vulnerable to outside influences. Much like Christian in Midsommar, modern Christians often attempt to treat all religions equally and do not single out their faith or lifestyle as better or more valid than any other. The millennial Christian writer Matt Walsh, in his book Church of Cowards, laments that in modern settings,

It is not enough for you to simply allow for the existence of sinful people and behaviors. You must accept them. […] It is quite possible to tolerate without accepting, which is why accepting is the point, not tolerating. The church, according to the culture, must do much more than tolerate our sins. It must accept–acquiesce to, assent to–those sins. 13

Interestingly enough, The Wicker Man itself foreshadows many of the situations depicted in Midsommar during its conversation between Sergeant Howie and Lord Summerisle. Lord Summerisle’s grandfather, the scientist who first attempted to grow crops on the island, was an atheist and only invoked the pagan gods and rituals to motivate the locals to work for him. However, Lord Summerisle goes on to explain that, “What my grandfather started out of expediency my father continued out of…love.” Lord Summerisle himself eagerly immerses himself in pagan beliefs and leads the rest of the islanders in their pagan rituals. The point that The Wicker Man seems to be making is that the materialism and lack of religion in the life of Lord Summerisle’s grandfather is ultimately what paved the way for his descendants’ wholehearted embrace of paganism. In much the same way, Dani’s unmet need for meaning and solace drives her to embrace the Hårga.

Both The Wicker Man and Midsommar depict a clash of cultures. The central characters in both movies come from a Christian-normative culture, though their level of knowledge and observance varies. Throughout their respective movies they explore a pagan culture that seems utterly alien to them. However, the underlying message of both movies seems to be that nobody can live without any sort of religious belief for very long. Eventually, if cut off from conventional religions like Christianity, people will begin to explore other means of spirituality and connection, no matter the consequences to themselves or others. Audiences who watch these movies are invited to reflect on whether they could resist the allure of the pagan cultures depicted and, if so, what if any spiritual beliefs hold them back. Either way, they will emerge with a greater understanding of the importance of spirituality.

Works Cited

- Travis, Ben. “Midsommar Director Ari Aster On Avoiding The Influence Of The Wicker Man.” Empire, 3 July 2019. https://www.empireonline.com/movies/news/midsommar-director-ari-aster-on-avoiding-the-influence-of-the-wicker-man/ Accessed 6 July 2020 ↩

- Gee, Oliver. “Swedish people just don’t understand small talk.” The Local, 2 July 2013. https://www.thelocal.se/20130702/48816 Accessed 23 June 2020 ↩

- The Wicker Man. Directed by Robin Hardy, performances by Edward Woodward and Christopher Lee, Lionsgate, 1973 ↩

- A24. “MIDSOMMAR | Official Trailer HD | A24.” YouTube, 24 May 2019. https://youtu.be/1Vnghdsjmd0 ↩

- Murdoch, Anthony. “Canadian archbishop: Selling euthanasia as ‘solution’ to suffering is ‘misguided.'” Life Site News, 15 May 2020. https://www.lifesitenews.com/news/canadian-archbishop-selling-euthanasia-as-solution-to-suffering-is-misguided accessed 23 June 2020 ↩

- Goins-Philips, Tre. “Beloved Pastor, Mental Health Advocate Tragically Takes His Own Life.” Faithwire, 10 September 2019. https://www.faithwire.com/2019/09/10/beloved-pastor-mental-health-advocate-tragically-takes-his-own-life/ Accessed 23 June 2020 ↩

- Acolytes of Horror. “How Midsommar Brainwashes You.” YouTube, 23 May 2020. https://youtu.be/gr2j0o_B2mw ↩

- Eberstadt, Mary. How The West Really Lost God. West Conshohocken, PA, Templeton Press, 2013 ↩

- Hills, Rachel. “What Every Generation Gets Wrong About Sex.” TIME Magazine, 2 December 2014. https://time.com/3611781/sexual-revolution-revisited/ Acccessed 28 June 2020 ↩

- Micky. “The History of Metal Music.” Rock My World, 12 June 2019. https://rockmyworld.com/the-history-of-metal-music/ Accessed 28 June 2020 ↩

- Bernstein, Adam. “Edward Woodward, 79, dies; British actor, spy in ‘Equalizer.'” The Washington Post, 17 November, 2009. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/11/16/AR2009111602636.html Accessed 28 June 2020 ↩

- Eberstadt, Mary. “A New Theory: The Great Scattering.” Primal Screams. West Conshohocken, PA, Templeton Press, 2019 ↩

- Walsh, Matt. “The False Virtues.” Church of Cowards. Washington, DC, Regnery Gateway, 2020 ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I love the analysis you wrote here; definitely gives more perspective on what Midsommar was drawing from. I’m not a pagan, but I have a lot of Swedish ancestry on both sides of my family, and I do feel a spiritual connection to the country. The film, as gory (and trippy!) as it was, was very beautiful—so many colors and lush compositions. I thought the music was astoundingly good as well, and the entire experience left me feeling very paranoid, as I’m sure the director intended.

I loved the broken relationship as well as the tragic feel to Dani has such a great drive for a story.

We still burn a wicker man at a festival every summer here in south-west Scottland.

Thing is, I’m pretty sure that festival was inspired by The Wicker Man, rather than the other way around.

My wife and I accidentally drove a couple of hundred yards down a country road in Norfolk, only to find a bunch of people making a wicker man. I think we broke the land speed record for reverse-gear.

Funny antique film, worth its cult status.

TWM is one of those rare films that actually reflects something unique in this society – I’m not sure quite what, but it’s something that gives the film an enduring appeal to the people of these islands.

There is a sinister quality to these movies but it’s not so far from some of the late 60’s early 70’s Dr. Who episodes.

Have you watched Chambers on Netflix? If you do, I’d be interested in your thoughts on it. It has some similarities to Hereditary and Midsommar.

A good essay and I enjoyed Midsommar, The Wicker Man, not so much.

I’m not much of a film-watcher, so its no surprise I have never heard of either of these films. But they both sound like they are worth watching!

The Wicker Man is a horrible film.

It had a great deal to do with stimulating prejudice against modern Pagans and Witches.

That prejudice caused children to be taken away from innocent families and many others to be harassed into misery (and scared kids) by our wonderful Social Workers.

Er, every Pagan and Witch I’ve ever known loves this film. Remember our coven watching it upstairs at Leeds Peace Centre circa 1990.

Totally agree, all my pagan and Wiccan friends love it. One of my favourite films..

This is just sheer nonsense. I’d be astonished if you could find any evidence that the WM was cited by the proponents of the Satanic abuse panic.

Funny that. I knew families from the ‘Orkney Scandal’ and not one of them mentioned The Wicker Man.

Love, love, love TWM. It’s the most unique mix of a musical with a constant undercurrent of sinister weirdness. Brilliant!

I’ll never look at Swedish women the same again after seeing Midsommar.

After much reflection I’ve come to the conclusion that what was portrayed was essentially just a cult. Things appear calm and beautiful on the surface but eventually the illusion vanish and reality barges in. Like any cult they must replenish their numbers and we are shown how that is accomplished. But jealousy rears it’s ugly head and the offerings go up in flames.

There’s nothing fascinating, engaging or dramatic in Midsommar. For a movie that is supposed to be frightening and clearly ‘academic’, what you’re left with is the emperors new clothes.

The brilliant trick of the ’emperor’s new clothes’ accusation is it doesn’t actually expose the illusion so much as reverse the subject.

What the hell happened? I was wondering that after watching a movie set in the middle of the woods involving Nordic teenagers.

Wicker Man was never shown on TV while I was growing up, so I was held hostage to the whims of local video shops. So when I was a very young adult in the early 90s, my entire exposure to the film up to then was via film books (mostly about horror) from the 70s and 80s. That was when I finally saw the VHS tape on sale at Now and Then Books (sadly now gone) for about $75. Alas, I was a poor student. It wasn’t until the 2000s, and its release on DVD, that I finally saw it. Well worth the wait, although I probably found Ekland’s performance less exciting than I would have 10 or more years earlier. I still consider the recent remake to be quite criminal.

Bit of a tangent: In some ways I miss hunting down video nasties in strange rental stores since DVD (and now torrents) have made so many movies more widely available. Yes, it makes things easier, but it also takes away some of the thrill. And it turns out many of those “forbidden” films are less mind-blowing than you’d been led to believe. My memories of looking at stills and trying to piece together films in my mind from brief descriptions were probably more interesting. I sometimes feel sad for kids who have access to everything made so easy, but they’d probably just think I’m nuts if I articulated that.

Cannibal films, etc are just not the same when they don’t come in boxes covered with cheap art still and poster reproductions and oriental text.

Woodward is so good in this film he makes me root for a religious bible basher. He does have my sympathy, mainly because of his motivations in upholding the law and finding the potential sacrifice victim.

And Christopher Lee too. It doesn’t matter how crap the film is he is almost always great. Here, he is barely in it when you consider the length of the film but his scenes with Woodward and his screen presence make the film what it is. That chilling look at the end where you are left wondering whether he actually believes in what he is doing. “They will not fail.” There is the smallest hint that he is a conman in those eyes.

I first saw this when I was about 11 and it is still one of my favourite films to this day – over twenty years later.

I don’t think I’ve yet seen another film that comes even close to the atmoshpere created by this amazing film. All the aspects of it work wonderfully: the pagan music; the great acting; the structure and the great cinematography, all combine to make a really special finished article.

The only other film that comes close to the isolated claustraphobia that this film brings to life, that springs to mind anyway, is the original made-for-tv Woman in Black. I made the mistake of watching the disappointing recent remake of that. I won’t be doing that with the Nicholas Cage version of this one.

The Cage remake is truly one of the worse films I have ever had the misfortune to see – truly awful!

I’ve only watched this film once but I found the ending so disturbing I really don’t think I could go through it again. It’s a terrific film. Though that arse-waggling scene is a bit ridiculous, regardless of whose arse it actually is…

I can imagine Millenialism concluding in a New Pagan religion. It would just be a final troll to the sad Xers who got involved in all that New Atheism stuff, led by Dawkins and various other Anglo analytic philosophers.

I found Midsommar poorly paced and way too long, and not as deep as it thought it was. I mean, the bad boyfriend is even named “Christian” and then sewn into a bear’s hide and burned to death at the end, a fate that’s signalled from the arrival in Hårga (especially if you know ‘The Wicker Man’). It ain’t exactly subtle, or original. Every single character in this film is unable or unwilling to change their moral perceptions, or they are at the mercy of their own uncontrolled emotions, but it’s to the point of unbelievable stupidity – not the kinds of ciphers I expected to see in a so-called “art horror” film. Characters and themes are introduced and then sidelined in favour of grisly set pieces – okay, it’s horror, so we do expect *that* – but Dani’s grief is just a set-up for a mental downfall that turns her into a control freak. Simon and Connie, the only other PoC beyond William Jackson Harper’s Josh were introduced only to be killed off offstage, which seems to deliberately court the dreary old Hollywood trope that anyone not white won’t make it through to the end. The argument this may be what Aster intended is essentially yawnsome. Admirable intentions perhaps, but how exceptional it would’ve been if Dani’s grief had been properly explored, and the “evil” the Hårga are purging a metaphor for that.

I don’t think any piece of art – least of all film, which can only exist through extraordinary amounts of co-ordinated, talented collaboration – is throwaway, and bravo for the visual aspects but after Hereditary, for me Midsommar turned out to be a pretty disappointing experience.

The power of the last few scenes in Wicker Man says more than any amount of theological analysis ever could.

The Wicker Man is great fun, and well worth revisiting now and then. I recently saw Local Hero for the first time. Bill Forsyth’s film makes an interesting comparison with WM: outsider arrives in small, peculiar Scottish community with a particular mission. Except that in LH, the community’s idiosyncrasises are rather more benign. Amusing to see the two films side by side.

It works well as a little time-capsule piece.

A good film to watch for inspiration before a trip around Scotland is Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The locations are amazing and the fact the Mess’rs Gilliam and Jones chose to use real castles around the UK instead of wooden sets on a studio back-lot goes a long way to making the film engaging and authentic (if a word such as “authentic” can be applied to a film in which are cute white rabbit beheads several people and then gets blown-up by The Holy Hand Grenade of Antioch — this probably the most historically inaccurate moment in the film, followed closely by the coconut issue).

I just found The Wicker Man a nasty piece of work, not uncharacteristic of the early 70s in that respect. I don’t actually recall the music well, but think it was a representative slice of English folk music of the time – clunky, still being re-invented from next to nothing by people who hadn’t been playing that long, and something of a labour to listen to. Especially if it was someone trying to sing a ballad containing fertility imagery as portentously as possible.( Anyone who was ever in a 70s folk club will know what I mean.)

I dare say the people of the Hebrides would have been happier without the TWM branding of their part of the world.

I loved the inclusion of pagan elements in Midsummer to create another folk horror which will undoubtedly become a cult classic. The visuals were stunning and so was the use of sound. I hope Aster gets to do more horror films.

Florence Pugh is magnetic, I think she’s brilliant.

I’m actually not squeamish with gore in horrors (and I’m also a massive horror fan). But when I watched Midsommar on a flight I had to cover the screen to save me and all the people around me from the imagery. Was a great film though. I like your thoughtful analysis of it and TWM. You did a lot of research…

I think that one of the terrific things about THE WICKER MAN is that you can watch it as an atheist, a pagan or a Christian – and in each case you will get a satisfying experience.

As an atheist, it can be a commentary on the folly of all religions, and how they lead people to do destructive, terrible things – or to be blind to obvious dangers.

As a pagan, not only is it a riot of (1960s/70s) pagan imagery and ideas, not only does it present a very positive, functional world in which paganism predominates – it is also darkly amusing to see the sexually repressed and self-righteous interloper fall victim to a society he cannot accept.

And, as a Christian, it is a fairly classic story of a martyr – for all his faults, Sergeant Howie is a good man and he dies praising God.

Any of these readings is justifiable. It really impresses me that the film can work for several different audiences and deliver and intelligent and meaningful message to all of them.

Seems to me to be about a classic case of a cult. The audience are drawn in by the apparent attractiveness of the neo-pagan cult invented and lead by Lord Summerisle, seduced by it. Indeed, judging by some reactions, they are seduced to the extent that they end up viewing human sacrifice as something to be cheered

It’s true, it really is very even-handed. I’m not sure it would be possible to recreate such a balanced view of things today. The Wicker Man operates under the assumption that the audience, whether religious or not, already understands the important role played by religion in people’s lives, something directors can’t really take for granted anymore.

I will never forget, the shock and horror of the final scene, where the man and goat are burned inside the Wicker Man, as the pagans sing and dance.

Brilliant acting. Brilliant film.

I love a The Wicker Man, I accidentally realised after a visit to Kirkcudbright that I had been at a special place!

One of the measures of this films strange beauty is how badly wrong the remake got it, how it didn’t even approach the layered sophistication of themes at work.

It’s out there on its own and is a testament to its era.

The less said about the Nicolas Cage version the better…

I’d forgotten quite how many women Cage punched in that film. I’m pretty sure that when it came to the bees I was cheering on the locals…

The Cage version is one of the funniest films I’ve ever seen.

Very good analysis.

I first saw a clip of The Wicker Man in a scene from Danny Boyle’s film Shallow Grave, where Ewan McGregor’s character is watching the Wicker Man burning scene on television. I remember thinking, “Hmmm, that looked weird”, and hunting the film out. This was pre-DVD re-release days (I’m showing my age), so the VHS version I found was the “censored” version that didn’t feature Britt Ekland doing her weird tit-jiggle dance around in her bedroom to enflame poor Edward Woodward.

I’ve re-watched it many times since, and am always struck by how singularly weird and funny and disturbing it is – it has a tone like no other film I’ve ever seen, except maybe the 70s film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. It’s a tone that’s somewhere between camp and kitsch, but also rather creepy, as the “weirdness” or “perversion” of the community comes not from magic or special effects or CGI monsters, but from very normal looking countryfolk who just happen to be murderous pagans. Rosemary’s Baby achieves a similar effect with the benign nosy old neighbours who turn out to be Satanists. It’s the location of the weird in the everyday that, for me, gives the film its power and its weird fascination.

The ending of The Wicker Man is still genuinely shocking to me, especially as the film seems to side (or encourage you to side) with the cheerfully smiling pagans as they benignly sing their folk song while their sacrifice burns. Edward Woodward’s performance is very carefully calibrated – he can be seen either as a joyless puritan who gets his just desserts, or as the victim, or somewhere in between. You’re left wondering who’s view of the world is right – the Christian or the pagan, or whether they’re both wrong and what you’ve watched is just an act of group savagery. The paganism practised on the island looks home-made in a crotcheted-toilet-roll-holder way, and seems a little silly – but clearly much more fun than being engaged to Woodward the virginal police officer.

It’s also very, very funny, in a black-hearted mean kinda way, as the whole of the village blithely contrive to fool Woodward’s character and lead him into a trap. You’re just engaged enough with the mystery of the missing girl to want to see Woodward succeed in solving the “crime”, even though you’re rather enjoying all the dead ends he comes up against.

In some ways, the film is very dated – the costumes, the folky flute music, the interpretative dance, Britt Ekland and Lindsey Kemp – but somehow it doesn’t feel obsolete, and it retains its appeal. If you want further proof that the film is great, compare it to the truly execrable remake by Neil LaBute of a few years ago.

Next, I am watching Midsommar. Thank you.

For me, part of the fun of The Wicker Man is that it sort of encourages you to put yourself in the police officer’s shoes and speculate about what you would do if you were in his situation. I’ve often wondered if it would work well as a choose-your-own adventure book or video game (though it might be too late for that, since most people already know about the twist at the end).

I should also say that I think it’s a bit unfair to assume that Sergeant Howie is as humorless in his everyday life as he is for most of the movie. Remember that he spends nearly all of the movie’s running time exploring an island with a pagan culture he finds utterly bewildering, and we never really get to see what he’s like when he’s not investigating a crime. We don’t know what he’s like at, say, a Christmas celebration or an Easter picnic.

TWM remains a brilliant film with impeccable acting. It is weird in an Alternative Reality way. When I first saw it as a child, what freaked me out was the end, but I was in love with the films strangeness. I grew up watching the TV show Thriller, and TWM reminds me of that series. Weirdness in the UK, hinting at something far older living there that what a Christian upbringing would lead me to understand. I am somewhere between Pagan and Christian in my spirituality as an adult. It’s very hard to put my beliefs into words and I’m certainly not a Howie bible person, but I haven’t divorced myself totally from some Christian ideas. Yet quite distinct from churches and church theology.

I think what TWM does show so well is that people and their organisations are what usually damage a belief system.

On a weird note, my school sang Summer Is A Coming In at choir practice. I was maybe 10 then. Every time I sang it I thought of Diane Cilento and co dancing in front of the wicker man. That alone was just plain weird.

Thank you for a great thematic comparison of the movies. I also appreciated the earlier comment of the movies as a commentary on the folly of any religion, perhaps even extreme belief. The problem for me was that I felt the folly extended to the way Midsommar was made. Midsommar was strangely simplistic and binary, particularly when it came to the portrayal of the so-called “pagans.” Just like there is no such thing as “Christians” being one thing, there is no such thing as “pagans” being one thing (over-sexed, submitting to a leader, eating with relish, sacrificing humans – the first Christians were accused of all those features, too, and they did none of them but the eucharist, baptism, and “brotherly” love were all misinterpreted). Indeed, in “Midsummer” the pagans conveniently behaved as if they could check off all boxes in someone’s stereotype of “pagans” which I found disappointing coming from an otherwise non-stereotypical director at a time in history where we assume such binaries have been troubled. Perhaps we didn’t know better when the Wicker Man was made. But now don’t we? What do you think?

To be clear, I’m not trying to say that I think all pagans are the same, any more than I think all Christians are the same. My point is simply that the outsiders in these stories are in fact Christian (at least in a vague cultural sense) and the people they visit are in fact pagan–insofar as they practice a number of traditions that I associate with pagan belief systems. I didn’t have space here to elaborate upon some of the differences between Christian and pagan belief systems, but I talk about this more in my article on Lovecraftian cosmic horror. The way I see it, the sexual aspects of the stories are just a convenient shorthand for how blissfully unconcerned the pagans are with Christian morality regarding sex and relationships (in much the same way that human sacrifices shows their casual disregard for Christian morals about murder and human life).

For what it’s worth, I actually think The Wicker Man does a pretty good job of making paganism seem “normal.” It’s true that the pagans sacrifice people to their gods, but they otherwise seem to life in a fairly normal seaside town, with schools and shops and the rest of it. So, I think it shows, as well as it could have for the time, what a society would be like that was mostly normal, but just happened to kill people as part of worship.

Who is the author of the article?

What makes The Wicker Man a great film is how it refuses to choose sides.

Some people seem to be labouring under the misapprehension that The Wicker Man aspired to some sort of “authenticity”. Nothing about it is authentic, the mythology is made up in a mix and match style from whatever the writers could think of, the music isn’t by folk musicians and isn’t folk music. It was made with virtually no budget and when finished was almost trashed because no-one knew what to do with it. It’s a great film which manages to be “of it’s time” and simultaneously transcend it’s time. Testament to the makers originality of vision, even if it does look like a typical Hammer horror.

In Midsommar, I really enjoyed the symbolism and the weirdness of all the rituals, it was a feast for the eyes and brain.

I recently came from a pagan summer solstice festival where we all dressed in white for the main ritual. But other than that it was nothing like Midsommar.

I love Wicker Man and everything about it. Willow’s Song is unspeakably beautiful.

I liked both of these movies. They remind me of a mind control cult I was a part of (Twelve Tribes Communities) in my Christian days.

I’ve recently finished reading a book about the Pitcairn abuse cases and whilst reading is struck me as a cross between lord of the flies and the wicker man…who knows what people will come up with as acceptable practise when left to evolve their own society. I will be rewatching the Wicker Man soon with this in mind.

I always found the ending to be brilliant – but then I love a downbeat ending (the parallax view anyone?).

The Wicker Man is as much about the cynical manipulation of people of faith by the ruling elite as a cautionary tale on faith itself.

The Wicker Man is among my favorite films. I’ve owned it since it was issued on videotape, and yes, with all the bits. Britt Ekland at her most “bit”ness, if a wee bit witless.

Not only does it hold a mirror to small-mindedness in religious belief, it covers a vast array of class distinctions, religio-economic ties- and the essence of belief in anything is questioned. It is a classic, vastly underrated. Thanks for reminding me of it. I’ll dig it up tonight; with a bowl of popcorn and some lemonade, it’s a great summer night treat.

To me, Midsommar is about breaking out of the loneliness, selfishness and mental harm of individualised living in order to find peace in a community – something greater than yourself and your own ego (and all the afflictions related to it).

We all live by some kind of ‘belief’ whether that is of capitalism or atheism, or one of the worlds great religions, there is no neutral ground.

Let’s forget the beautiful music in The Wicker Man. Rough and folky but full of really surprising chord changes and riffs. A sound like no other, as unique the movie itself.

I really enjoyed your focused and developed discussion of the two films, even though I seriously can’t sit through most horror films. They set me on edge too much, and I usually end up leaving the room (if I’m watching them at home) or pleading to myself to never ever come to one again (if I’m in a theater).

As much as I liked the first half of your essay, I thought the second half of your essay moved away from that focused analysis of the films and into a discussion of what seems to me to be a very different and very complex topic, making what seem to me to be overly broad generalizations, such as this one: “The 1970’s, when The Wicker Man came out, were a time of tremendous cultural upheaval on both sides of the Atlantic. Religious traditions had less power and influence than ever before, a process that started in the 1960’s and continues to this day 8. People were experimenting with free love and alternative relationship styles 9. Popular music was becoming increasingly daring and controversial, and the relatively new genres of hard rock and heavy metal were gaining in influence 10.”

The 2014 Time article that you give as a source in that section of your essay (‘What Every Generation Gets Wrong About Sex’) challenges that notion that the 1960s or 1970s were the actual beginnings of all of those changes: “The truth is that the past is neither as neutered, nor the present as sensationalistic, as the stories we tell ourselves about each of them suggest. Contrary to the famous Philip Larkin poem, premarital sex did not begin in 1963. The ‘revolution’ that we now associate with the late 1960s and early 1970s was more an incremental evolution: set in motion as much by the publication of Marie Stopes’s Married Love in 1918, or the discovery that penicillin could be used to treat syphilis in 1943, as it was by the FDA’s approval of the Pill in 1960. The 1950s weren’t as buttoned up as we like to think, and nor was the decade that followed them a ‘free love’ free-for-all.”

Decades before the cultural conservatives whose names we might still recognize were panicking over heavy metal and homosexuality there were cultural conservatives panicking over rock music, Elvis, homosexuality, and Negroes on the radio. Decades before that they were panicking over jazz, interracial speakeasies, short-haired women, and, yup, you guessed it, homosexuality.

It’s definitely good to connect a specific analysis to a broader historical context, but it’s not easy to discuss a hugely complex topic such as historical context with oversimplifying it.

With Midsommar being one of my favorite films, this is a very cool comparison piece. The symbolism is layered.

I’m seeing a lot of pro-community, pro-collective ideas in the comments, but Midsommar is very critical of the communal life. Whatever leftover hippy utopianism one might feel gets smashed in this movie when the cliff scene happens — and it’s more of the same from then on.

In The Wicker Mam Howie not only is a stiff Christian but also an officer of the State. He doesn’t only despise the pagan way of life from his own beliefs but he’s also enabled to intervene as an agent. I feel the opening song which is about a woman leaving her lands in the opposite direction of Howie’s flight invites to a people vs. state level of analysis. Great fulm, great fable.

I have to watch Midsommar.

This seems to be an allegory of the modern age.