Thor’s Worthiness to Wield the Hammer

Thor is not an entirely new Marvel creation, unlike Captain America, the Hulk, Iron Man, and other superheroes populating the Marvel Cinematic Universe. The film Thor (2011) cleverly acknowledges its own sourcing of Norse mythology by including a fictional children’s book of stories, Myths and Legends from around the World by Anneka Sunden. This children’s book of myths is easily overlooked, but it serves several important functions. It acknowledges the film’s indebtedness to Norse mythology, reinforces the film’s exploration of the question of what it means to be worthy to rule, and ultimately allows the film to radically rewrite the Old Norse myths of Thor for a modern and American (or at least heavily Americanized) audience.

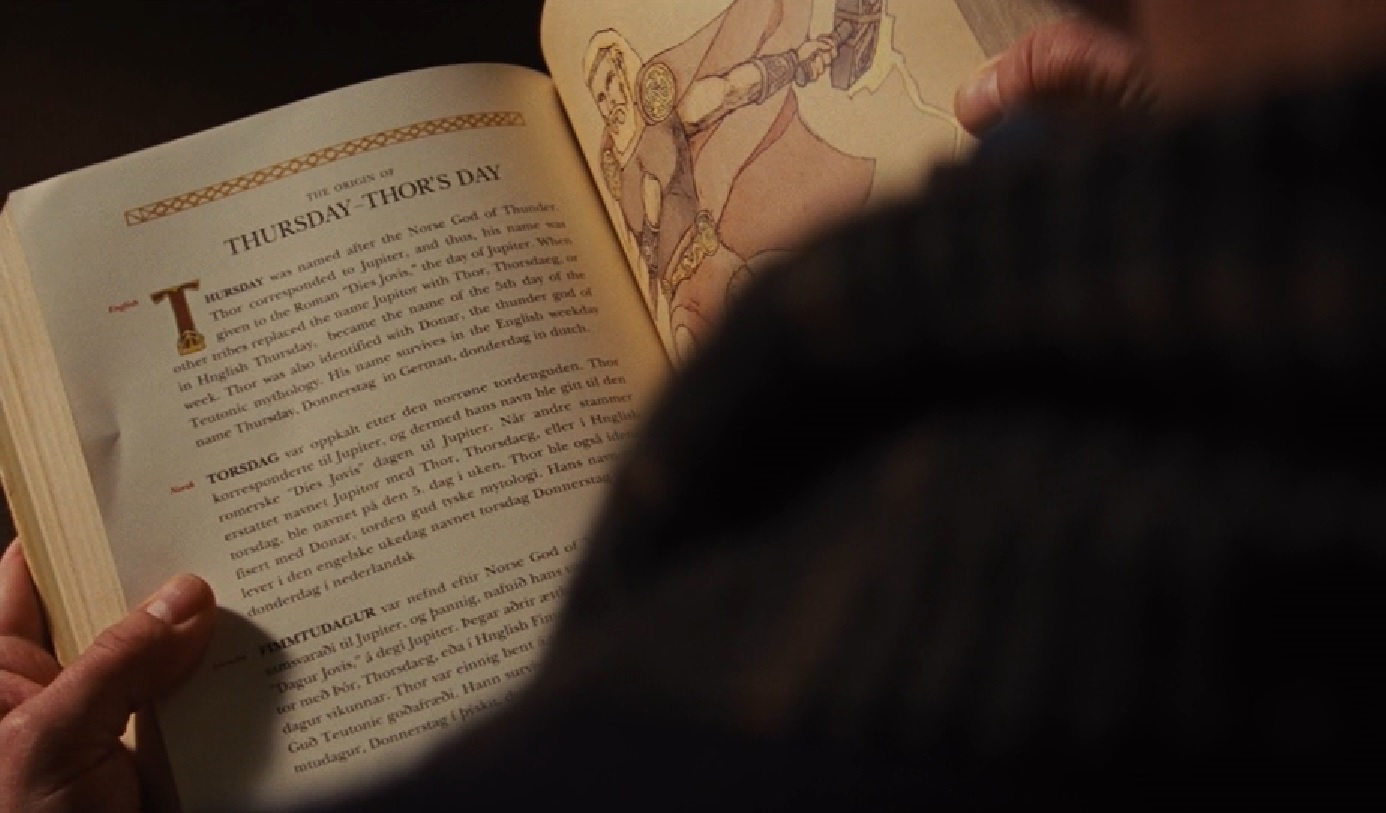

The connection between Thor and children’s stories is first made midway through the film, when Eric Selvig tries to convince astrophysicist Jane Foster that Thor, newly banished from his Asgard home to Earth, is delusional and dangerous. “Listen to what he’s saying,” Selvig says to Foster. “He’s talking about Mjolnir and Thor and Bifrost! It’s the stories I grew up with as a child.” 1 Selvig–whose fair eyes, hair, and complexion, coupled with his name and the slight lilt in his speech, signal his Scandinavian ancestry–picks up the children’s book of myths in the public library of the small New Mexico town in which much of the film is set. He uses the book to help make sense of Thor’s implausible origin.

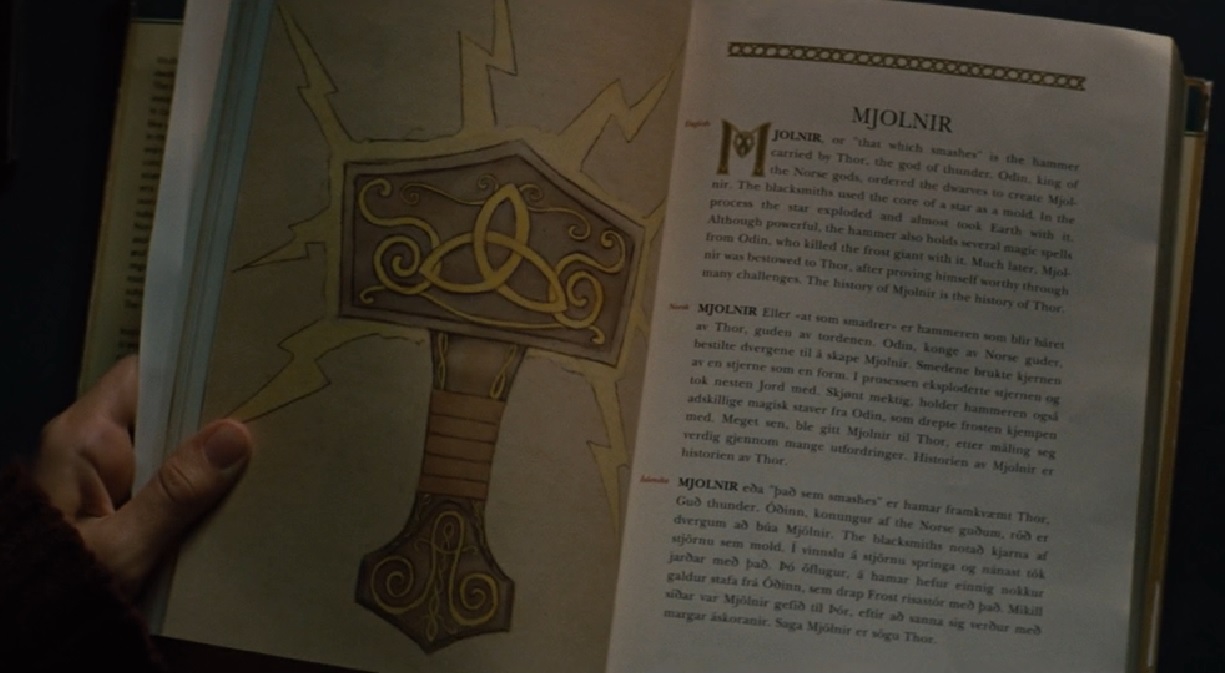

The two illustrated entries from Myths and Legends from around the World that Selvig glances over while in the library–one titled “Bifrost: The Rainbow Bridge to Asgard” and the other “Thursday–Thor’s Day”–are given enough time and space on the big screen for viewers to read them at least partially, to see that the book presents each short entry in English as well as in two or more North Germanic languages, and to view the accompanying hand-drawn illustration of Thor that resembles the film’s title hero. This same children’s book of myths reappears some fifteen minutes later in the film. Darcy Lewis, Foster’s research assistant, stumbles across and shares with Foster and Selvig two more entries–one on Mjolnir, the other on Loki. These entries prompt a short and spirited debate. Among other things, the characters question the conventional distinctions between fact and fiction and touch on the notion that early human civilizations might have been visited and influenced by technologically advanced extraterrestrials, a notion often called the “ancient astronaut theory.” (For an analysis of the “ancient astronaut” as contemporary myth, see the discussions by Michael Carroll and Andreas Grünschloss.) 2

In a close-up lasting three seconds, the text and illustration for the entry on Mjolnir in Myths and Legends from around the World deliver a mini-lesson in ancient Norse mythology to the film’s modern audience, presenting the content of that mini-lesson as real mythology and perhaps even as real history. The book’s passage on the origin of Thor’s hammer is presented in the film as merely the translation into English of a genuine Norse myth that might have grown out of real-world visitations by an advanced alien culture and that might still be told today by parents to their children in some northern European village or North American town. The passage on Mjolnir reads:

Mjolnir, or “that which smashes” is the hammer carried by Thor, the god of thunder. Odin, king of the Norse people, ordered the dwarves to create Mjolnir. The blacksmiths used the core of a star as a mold. In the process the star exploded and almost took Earth with it. Although powerful, the hammer also holds several magic spells from Odin, who killed the frost giants with it. Much later, Mjolnir was bestowed to Thor, after proving himself worthy through many challenges. The history of Mjolnir is the history of Thor. 3

Only in the most general sense does this brief account of the history of Thor’s hammer from the children’s book in the film agree with the detailed account in the Prose Edda, an early 13th-century collection of myths in Old Norse: the hammer is indeed created by dwarves, named Mjolnir, and wielded by Thor. However, in these source myths there is no decree from Odin that the hammer be created, no near-destruction of the planet as it is forged, no passing of the hammer from Odin to Thor, and no need for Thor to “prove himself worthy” to wield it. According to Snorri Sturluson’s Prose Edda, the dwarf brothers Brokkr and Sindri forge the hammer in response to Loki’s taunt that they would never be able to produce anything greater than their own previous masterpiece. The only real danger in forging the hammer is that they might fail and embarrass themselves, largely due to Loki’s efforts, as a fly, to distract Brokkr from his task by biting him on the eyelid strongly enough to draw blood and thereby impair his vision. The hammer Mjolnir–which proves to be far greater than anything the dwarves had previously created–is simply awarded to Thor without question. 4

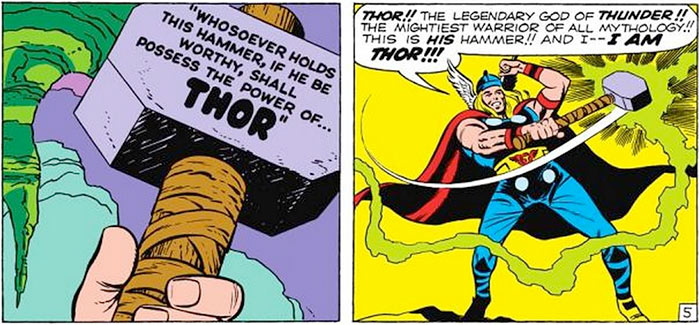

The condition that Thor would need to prove himself worthy before he might wield the hammer is found not in the Norse myths but rather in the 1962 comic book that introduces the character of Thor into the Marvel (pre-cinematic) Universe. In the opening pages of Journey into Mystery #83, the reader is introduced to Dr. Don Blake, a physically frail American on vacation in Norway, his ancestral home. Blake flees into a small cave to evade a scouting party for the invasion force of green Stone Men from Saturn. In a secret room of the cave he finds a “gnarled wooden stick,” an “ancient cane,” that when struck against the side of a boulder transforms itself into the hammer Mjolnir and Blake into the god of thunder. 5

Placed just after Blake’s discovery of the transformative power of the hammer, a panel in Journey into Mystery #83 offers a close-up of the hammer as it is held in the hero’s left hand. The hammer’s inscription asserts that not just anyone is able to access the power of the weapon: “Whosoever holds this hammer, if he be worthy, shall possess the power of … THOR.” 6 Some six years later, a 1968 volume of the Marvel comic book Thor–the cover of which promises the reader “The answer at last!”–explains that Blake has always been Thor but did not know that he had been confined by his father Odin to a frail human form and had been banished to Earth so that he might learn the lesson of humility. In this unveiling of the backstory for the comic book hero, Odin explains to the now redeemed Thor that he was reunited with his hammer only after he had learned that important lesson. 7

The motif of the hero needing to prove his worthiness before he can retrieve the magical weapon from its resting place and rightly ascend the throne is certainly much older than the 1962 comic book. It can be traced at least as far back as the early 13th-century Merlin romance by Robert de Boron, in which a sword embedded in an anvil atop a stone may only be pulled free by the one true king, the one person with the undisputed right to rule. As observed by the archbishop in this medieval account, the sword itself bears an inscription similar in both structure and content to the inscription found on the hammer in the 1962 comic book: “whoever could draw the sword from the stone would be king by the choice of Jesus Christ.” 8

Indeed, the film Thor incorporates elements of this now famous tale of the sword in the stone in ways that are at times purely comic and at times highly dramatic. On the comic level, the crater produced by the hammer’s impact draws a great deal of attention from the locals, who bring to the site their lawn chairs and coolers, their trucks and grills, and who take turns attempting to lift (or, in the case of Stan Lee’s cameo appearance, to pull free by chaining to the back of a pickup truck) the hammer from its resting spot in the crater’s center. On a dramatic level, after fighting his way past guards and slogging through rain and mud in a rousing action sequence, Thor similarly fails to lift Mjolnir from the spot to which it has fallen to Earth; he looks skyward, bellows in a mixture of rage and despair, and resigns himself to defeat.

Neither the Old Norse myths nor Arthurian romance serve as the primary source for the film Thor. Rather, the film draws extensively on the illustrations, overall storyline, and specific language of “worthiness” that was developed in the Marvel comics of the 1960s, with some changes, both major and minor. Whereas in the original comics Blake/Thor remains unaware of his true nature for years, the Thor who is introduced in the 2011 film is made painfully aware of his failure to live up to the standards of the Allfather. Following Thor’s incursion into the realm of the Frost Giants against his wishes, Odin strips Thor of his armor and his strength, dwelling on the idea of worthiness by repeatedly naming its opposite:

Thor Odinson, you have betrayed the express command of your king. Through your arrogance and stupidity, you’ve opened these peaceful realms and innocent lives to the horror and desolation of war! You are unworthy of these realms, you’re unworthy of your title, you’re unworthy … of the loved ones you have betrayed! I now take from you your power! In the name of my father and his father before, I, Odin Allfather, cast you out! 9

Similarly, the words that are found engraved on the side of Thor’s hammer in the comics are instead spoken by Odin early in the film. In the film, the hammer itself does not bear the words explaining the required worthiness of its wielder, but a trefoil (a three-leafed pattern made by interwoven lines) appears briefly on the side of the hammer as Odin holds it near his mouth and pronounces the statement that has been taken directly from the first issue of the Thor comic books from more than fifty years earlier: “Whosoever holds this hammer, if he be worthy, shall possess the power of Thor.” 10 The trefoil reappears twice in the film as a reminder of that condition of worthiness, first when Thor fails to lift the hammer and then again when, through his selfless act of sacrifice, he redeems himself in Odin’s eye, causing the hammer–with the speed and precision of a guided missile–to find its way back to him and to restore him to life.

In short, the film is all about a transformation of Thor’s character from a state of arrogance to one of humility, from brashness to wisdom, and from unworthiness to worthiness, a transformation that has been noted in many published reviews of the film. Following his return to Asgard and moments before their climactic battle, the title character and his brother Loki engage in a brief dialogue that makes explicit this dominant theme of the film: the hero must change internally–above all else, he must learn the value of diplomacy and humility and must be willing to sacrifice himself for the good of his people–if he is to wield the hammer and succeed Odin as the rightful ruler of Asgard. Thor initiates the dialogue by asking Loki to explain the reasons for his deceit, his attempt to kill his brother, and his genocidal plan to destroy the Frost Giants of Jotunheim. Loki challenges him to explain his “new found love for the Frost Giants,” to which Thor replies simply: “I’ve changed.” 11

Reminders of the internal change in Thor’s character appear no fewer than three times in The Avengers (2012). 12 First, ever optimistic about the possibility of his brother’s redemption, Thor explains to Loki what he has come to recognize as the importance of humility in anyone who has power over others:

Thor: You think yourself above them?

Loki: Well, yes.

Thor: Then you miss the truth of ruling, brother. A throne would suit you ill.

A second example can be found in the conversation with a prominent agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. Here, Thor demonstrates his awareness that Asgardians, when projecting their immense military power beyond their borders, often cause more harm than good: “We pretend on Asgard that we are more advanced, but we, we come here battling like bilgesnipe.” He goes on to explain that those animals are physically powerful and “trample everything in their path.” Finally, Thor’s past arrogance returns briefly when he, along with the other assembled Avengers, is manipulated by Loki’s scepter and exclaims derisively: “You people are so petty. And tiny.” Under the influence of the artifact, he regresses, abandoning for just a moment the lessons in humility and selflessness that he had learned on his first visit to Earth.

Thor as Myth: A Campbellian Approach

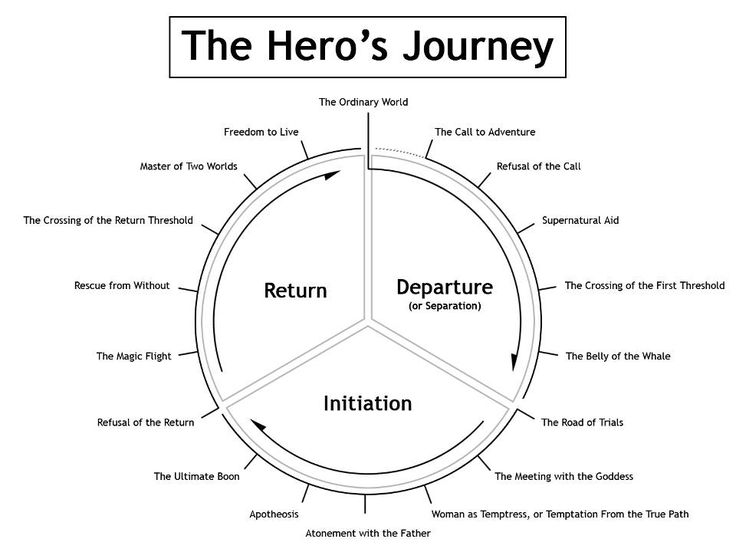

Thor’s change in the course of the 2011 film can be understood through two very different yet complimentary approaches to the analysis of myth: the Campbellian and the Barthesian. The first approach, generally the more familiar of the two, follows the model of the Hero’s Journey as presented in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949) and further popularized by two documentaries in the late 1980s, The Hero’s Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell and Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth. 13

The Campbellian approach to myth traces the transformation of the individual hero through three loosely defined parts of the story: Departure, Initiation, and Return. The hero moves from the world of the known into the much larger world of the unknown, experiences one or more trials (often including a symbolic death and rebirth), and ultimately returns to the known world and to society as a more complete and developed person who bears something that he has gained along that way–a “boon,” to use Campbell’s term–from which all people will have the opportunity to benefit. 14 Each of these three parts of Campbell’s model of the Hero’s Journey contains five or six stages. No individual myth of the hero is expected to illustrate in detail all 17 stages of this overall pattern, this monomyth, but a number of the stages–including nearly all of those in the middle part, Initiation–are clearly present in Thor: The Meeting with the Goddess (Foster instructs Thor), Atonement with the Father (Odin forgives Thor), Apotheosis (Thor regains his hammer, armor, and strength), and the Ultimate Boon (Thor acquires the humility necessary to become a just ruler).

In this Campbellian reading, among the other roles that Foster might play, she appears to function most clearly as an aspect of the Goddess. As the embodiment of the divine feminine, Foster presents Thor with an alternative to the brash, hypermasculine way of living that caused his argument with Odin and his banishment from Asgard in the first place. In the stage of The Meeting with the Goddess, Foster offers invaluable advice that operates on at least two levels. Foster’s admonition to Thor in the diner that he should learn to “ask nicely” and should engage in “no more smashing” after he throws a coffee mug to the floor, causing it to shatter, seems simply a corrective to his unnecessarily rude and destructive behavior, but her words soon take on a second, unexpected meaning. 15 Having been stripped of his super strength and metallic body armor by Odin and having failed to retrieve his hammer–whose very name, Mjolnir, is glossed in Myths and Legends from around the World as “that which smashes”–Thor learns from Foster in this stage that there are ways other than brute force to solve a seemingly insurmountable problem, such as a giant robot or enchanted suit of armor that simply will not die. The approach that she implicitly advocates and that is ultimately embraced by Thor when he faces the Destroyer is diplomatic: one should proceed by “ask[ing] nicely,” showing vulnerability, and seeking reconciliation.

Thor’s four Asgardian allies prove unable to stop the Destroyer from wrecking storefronts along the small town’s main street, including the diner in which Thor receives his guidance from the Goddess. Thor sends his allies and the townsfolk to safety, throws down the metal shield he had been carrying, approaches the Destroyer alone, and appeals to Loki, who is controlling it from the king’s throne in Asgard. Thor delivers a slow, heartfelt apology and offers up himself as a sacrifice to appease Loki’s taste for destruction: “Brother, whatever I have done to wrong you, whatever I have done to lead you to do this, I am truly sorry. But these people are innocent. Taking their lives will gain you nothing, so take mine, and end this.” 16 The Destroyer remains still for a moment and then delivers the fatal blow. Some critics have compared this moment to the gunfight in a classic Western, but the scene of Thor’s self-sacrifice more clearly echoes the Crucifixion in many details, including the wooden, cross-like utility poles in the background to the woman kneeling and weeping at his side to his final words (“You are safe,” and “It’s over”). Thor’s self-sacrifice brings about the next stage, Atonement with the Father. Confined within the Asgardian equivalent of a hyperbaric chamber, Odin appears comatose yet, as the close-up of his face suggests to the viewer, is indeed following the events on Earth. A tear trickles from the eye of the all-seeing Father, and the lost hammer begins to stir, flies through the sky, descends toward the fallen hero, and is gripped by the suddenly revived Thor.

In keeping with Campbell’s model, the stage Apotheosis immediately follows. Thor’s self is quickly reintegrated. He stands upright, bathed in bright light with his hammer held high, as his armor returns and encases him, hardening his body once again. Foster confirms his supreme status with a slow pronouncement that signals both amazement and recognition of his returned divinity: “Oh… my… god!” 17 His power restored, Thor deflects the Destroyer’s attacks and defeats it. The extensive mirroring of the Christian salvation story in Thor’s apotheosis is at odds with the pre-Christian myths on which this story of Thor is based and rewrites those myths in multiple, interesting ways. Even the illustration of Mjolnir in the children’s book within the film may be viewed as a thinly disguised cross. The Thor’s pendant on which the book’s illustration in the entry on Mjolnir is based is worn with the hammer’s head pointed downward. In the book’s illustration within the film, the head of the hammer points upward and is surrounded by a halo of lightning or divine light.

The Destroyer, with its body of shiny metallic scales and spikes and its blasts of fire, seems very much an embodiment of the Campbellian dragon, a beast that must be figuratively confronted and slain in order for the hero to transcend his previously limited experience. In Campbell’s schema, however, the Destroyer is not simply a dragon but rather the final dragon, “that self-generated double monster” that embodies everything that this newly-changed Thor wishes not to be: a mindless, even soulless, hard shell of a man whose only option is to smash the things around him. 18

The Ultimate Boon acquired by Thor in the final stage of the Initiation phase of Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, the thing that he is to bring back with him to Asgard and to share with his people for the benefit of all, is not simply the hammer Mjolnir. Rather, the boon is what has come of his reeducation by the Goddess/Jane Foster: a softening, maturing, and balancing of emotions. This internal change makes Thor worthy to wield the powerful weapon and to ascend the throne. Foster’s central role in the transformation of Thor’s character is confirmed a little further into the film, when Loki taunts Thor: “I don’t know what happened on Earth to turn you so soft. Don’t tell me it was that woman. Oh, it was!” 19

Once past the stage of the Ultimate Boon, however, problems begin to emerge with a conventional Campbellian reading of Thor. The title hero returns with the Ultimate Boon to Asgard, as Campbell’s model would predict, but the final battle with Loki that awaits him there is not so easily accounted for by the model of the Hero’s Journey, nor are Thor’s changed feelings about Asgard and the other realms. Back in Asgard at the film’s end, Thor has defeated Loki and ascended the throne, yet he is somber and distant rather than reintegrated into his world, as Campbell’s model would predict. The brashness and bravado that he displayed at the opening of the film–where he strutted before assembled crowds, partied loudly with friends, and allowed himself to be manipulated so easily by Loki into launching a retaliatory strike against the Frost Giants–has been replaced by wisdom, sullenness, and a sense of isolation from the very people he is to rule. Thor’s true home is now Earth, and he wants nothing more than to be reunited with Foster.

Thor as Myth: A Barthesian Approach

A second theoretical approach for analyzing myth, represented by Roland Barthes’ Mythologies (1955), can help resolve the problems that emerge when applying a purely Campbellian approach to the final six stages of the Return in the story in Thor. This second approach examines myth not as a creative way to present universal human truths and values through the journey of a single, heroic individual but rather as an effective strategy through which institutions seek to legitimize themselves by concealing their morally complicated or compromised histories beneath a surface story of universality, simplicity, and naturalness. Barthes writes in his long essay “Myth Today” that appears at the end of Mythologies:

Myth does not deny things, on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification, it gives them a clarity which is not that of an explanation but that of a statement of fact. … it organizes a world which is without contradictions because it is without depth, a world wide open and wallowing in the evident, it establishes a blissful clarity: things appear to mean something by themselves. 20

A Barthesian approach to the film does not examine the simple, innocent, and pure story of how Thor has changed from braggart to hero. Rather, it examines the morally less clear, far more contradictory account how he has been changed from the Thor originating in Norse mythology to a new god of thunder so that he might serve a new audience and new social and political purposes. None of the published reviews offer a Barthesian reading of the film, but Eric Hynes comes closest to suggesting such an approach in the closing sentence in his scathing review in The Village Voice: “Marvel continues to polish off its mid-century hyper-masculine heroes when what we really need is a new mythology for this more ambiguous age.” 21

Employing Barthes’ approach to myth, Jonathan Broussard argues that by consistently representing the title character in the first half of Thor as “the ‘ignorant barbarian’ in need of rescue by modern America, the film can create a myth of ‘blissful clarity’ in which the United States functions as the primary civilizing force of the world by educating the ‘barbarian’ so he becomes a ‘middle-class, White, American hero.’” Broussard connects some key details of the site of Thor’s education and civilization in the film–the small-town American diner and the coffee mug–to the historical roles of the coffeehouse and the diner. Broussard summarizes published scholarship on how the coffeehouse contributed to the move from hierarchical monarchies to modern and more egalitarian democratic governments and how the American diner helped forge a largely homogeneous American identity in the post-World War II era out of diverse immigrant groups and social classes.

Broussard’s approach allows him to make sense of the events in the final phase of Thor’s journey, the return to Asgard. By the end of the film, he argues, Thor has become “a tool for exporting discourses of American superiority and the need for American protection from tyranny, because, as the film depicts, Thor would not be worthy to wield Mjolnir, and by extension worthy to save Asgard (other countries), if he had not become Americanized.” Although he does not examine the representation of Thor in the comics of the 1960s in any detail, Broussard notes that the changes in the hero’s appearance are part of this transformation of the Norse god into the American superhero: “The blond hair and blue eyes that mark all Marvel iterations of Thor as a Norse god are absent in the mythic texts, which depict Thor as having red hair and red eyes.” 22

Thor as (naturalized) American Superhero

The overall trend in the comic books of the 1960s and the films of the Marvel Cinematic Universe is to radically redraw the character of Thor in a way that makes him no longer recognizable, beyond surface similarities such as his name and his favorite weapon, as the figure of a pre-Christian and early Germanic mythology. Instead, this new representation of the Old Norse god aligns him neatly with the popular imagining of contemporary America, with its collection of stories–stories that are grounded in both the religious and the secular and that weave together strands of divine sanction, white male privilege, and military might–of the powerful man’s heroic journey away from selfishness and arrogance toward humility, service, self-sacrifice, and rule. Vincent M. Gaine argues in his essay “Thor, God of Borders” that the 2011 film should not be described “as simply or entirely ‘American’” because of the broad mix of ethnic and national identities that are present among both the citizens of the fictional realm of Asgard and the film crew responsible for the production of that fiction.” 23 The story told by the film, however, obscures its origins in transnational collaborations and instead emerges as entirely American. Thor is no longer the Old Norse god; he has been recast in his new role as naturalized American superhero.

Through Thor, the character of the United States, the country in which Thor’s personal growth is made possible, is also recast. In this modern retelling of the Norse myths, the power of Thor is aligned with the superpower of the United States. Just as the personal story of the individual hero can be paired with the redemptive journey of the nation for great rhetorical effect–to draw on the arguments in Robert Jewett and John Shelton Lawrence’s influential study The American Monomyth–Thor’s change within the film suggests by analogy that the United States has proved itself worthy to wield its own metaphorical hammer. 24 (It is no great stretch here to see Thor’s hammer as a metaphor for atomic weaponry. The account of the creation of Mjolnir presented within the film suggests the harnessing of nuclear power–although it is fusion, not fission–in its reference to using a star’s core and producing a super powerful explosion that nearly destroys the planet.) In radically rewriting its source myths, the film Thor recasts the projection of military, economic, and cultural power by the United States beyond its borders as the selfless act of a worthy nation led by a powerful but humble warrior-king, one man who proclaims to the would-be tyrant, as Thor proclaims to Loki, that “the Earth is under my protection.” 25

Works Cited

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Carroll, Michael. Winter 1977. “Of Atlantis and Ancient Astronauts: A Structural Study of Two Modern Myths.” The Journal of Popular Culture 11:3. 541-50. Grünschloss, Andreas. March 2008. “‘Ancient Astronaut’ Narrations: A Popular Discourse on our Religious Past.” Fabula 48:3/4. 205-28. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Sturluson, Snorri. 2005. The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology. Trans. Jesse L. Byock. London: Penguin. Pages 92-93. ↩

- Lee, Stan and Larry Lieber (w), Jack Kirby (p), and Joe Sinnot (i). August 1962. Journey into Mystery #83. Marvel Comics. Page 4. ↩

- Lee, Stan and Larry Lieber (w), Jack Kirby (p), and Joe Sinnot (i). August 1962. Journey into Mystery #83. Marvel Comics. Page 4. ↩

- Lee, Stan (w), Jack Kirby (p), and Vince Colletta (i). December 1968. Thor v1 #159. Marvel Comics. ↩

- Boron, Robert de. 2001. Merlin and the Grail. Trans. Nigel Bryant. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. Page 107. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- The Avengers. 2012. Dir. Joss Whedon. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Campbell, Joseph. 2008. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Novato: New World Library. The Hero’s Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell. 1987. Dir. Janelle Balnicke and David Kennard. Holoform Research Inc. Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth. 1988. Perf. Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers. PBS. ↩

- Campbell, Joseph. 2008. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Novato: New World Library. Page 23. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Campbell, Joseph. 2008. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Novato: New World Library. Page 110. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

- Barthes, Roland. 1972. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang. Page 143. ↩

- Hynes, Eric. 4 May 2011. “Thor’s a Bore.” The Village Voice. http://www.villagevoice.com/film/thors-a-bore-6430673. ↩

- Broussard, Jonathan. 3 April 2015. “Taming the Thunder to Harness the Lightning: Thor as a Mythic American Hero.” Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association National Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA. ↩

- Gaine, Vincent M. 2015. “Thor, God of Borders: Transnationalism and Celestial Connections in the Superhero Film.” Superheroes on World Screens. Ed. Ryna Denison and Rachel Mizsei-Ward. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 36-52. Page 37. ↩

- Jewett, Robert and John Shelton Lawrence. 1977. The American Monomyth. Garden City: Anchor Press. ↩

- Thor. 2011. Dir. Kenneth Branagh. Marvel Studios. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thank you for this informative article. I am very interested in Norse mythology and the culture that embraced it.

Ragnarok actually has some interesting, subtle points about colonialism, conquest and santizing of history.

Thanks for your comment. I obviously need to take a closer look at that film!

I think people in the middle ages were largely hardened against our ideas of sorrow and apprehension.

I used to love Norse legends when I was a kid – them and Russian fairy tales. I read through them with my daughter a while ago (she lapped them up) and was struck by how incoherent their cosmology was – it’s the most jumbled bundle of contradictions, memory lapses and missing explanations.

I still love them though.

The inconsistencies are mostly because we don’t really know what the original Norse mythology was. Most of the sources where we get the legends are from the 13-16th centuries – ages after the Norse were doing their tromping around, just like how there are a ton of inconsisitencies with Greek mythology. It’s also why much of Norse mythology matches up so well with Christianity. Part of that is because Christians were writing down oral stories and modifying them to fit their world view, and the other part of that is that they were skewing Norse mythology to make the pagans more comfortable with Christianity (like how they moved Jesus’ birthday to Christmas to match with the solstice).

Myth is inherently inconsistent, I think. Even in ancient Greece there were multiple, contradictory versions of individual myths. See, for example, this statement from Bernard Evslin’s Greek Mythology: “The cycle of tales that make up the Argosy are among the earliest in Greek mythology. As has been seen, there is no ‘authorized text’ of any myth, and particularly none of this cycle, which varies wildly in all its versions.”

Chris reminds me a bit of Heath Ledger, not just the look and the voice, but something in his sensibility and approach to the work…

This was a brilliant article. As a Viking school visitor (I go to schools in costume to teach the children about Vikings), I get a LOT of questions about Marvel Vs Myth, usually when I start speaking about the Gods and they all get excited and start telling me about the plotlines of the films. I also adore the films however, and we must remember that the very premise of the films (and the comics upon which they are based) is that the Asgardian aliens visited earth in the past and became the basis for the myths, not the other way around. It’s like Stargate, only with Norse Gods instead of Egyptians.

Essentially these are sci-fi movies and should be enjoyed with a healthy serving of salt with a side of suspension of disbelief. If we’re going to have a go at a media company for being inauthentic, we should start on the History Channel’s “Vikings” which, whilst containing some authentic elements, is almost worse because it’s saying “here’s enough real stuff to make you think the black studded leather is ok”. Great fun though! (even if for some reason Uppsala in the Swedish flatlands is portrayed as forested mountains with a Norwegian 12th century stave church.) STOP! Stop now…breathe….

Great comment. I think you’re absolutely right about the History Channel’s “Vikings” as well as just about anything on the History Channel.

For me, inauthenticity isn’t a huge problem in itself, as there’s a lot we’ll never know about previous historical periods and there’s always going to be at least a little of ourselves and of own imaginings in the stories and histories that we tell. For me, the real problem is lack of reflection and abstract thinking. We often take stories much too literally, turning them into historical reality and literal truth. I agree with you that we can enjoy stories of just about any kind even while we remain a little critical of them. Like you say, they should be “enjoyed with a healthy serving of salt with a side of suspension of disbelief.”

Chris brings a physical presence and a certain amount of arrogant self belief in his superiority to the role.

Most importantly though, i think he actually convinces you he is a superhero, not just acting the part. In many sci-fi, fantasy and legendary movies, you don;t really come away with the feelings that the actors have immersed themselves in the part, perhaps because even at a subconscious level they believe it is “silly”. With Thor, Chris Hemsworth convinces you that he is a God who, if you even slightly piss him off, will ruin your entire year.

Did not really expect much from the Thor films but was very pleasantly surprised…really looking forward to the fourth one.

I recently watched all the previously-released MCU films in a week-long binge — have to catch up on everything I’ve missed in the last decade before Infinity War! — and while I understood and grasped a lot of the parallels (intentional or not) regarding the various sociopolitical themes in the Earth-bound stories like the Captain America and Iron Man films — particularly since I was watching with an eye towards how vibranium and Wakanda was involved with the rest of Earth up until Black Panther’s actual first appearance, since Black Panther was my hook into the MCU in the first place — I always saw the Thor movies as this weird side venture that just existed for the sake of having a genuine space fantasy element in the MCU. Of course, given that Thor and co. are ultimately based on Norse mythology, I knew there was something rubbing me the wrong way about how benign these inspirations of Viking legends were being portrayed. More than anything else, I appreciate how Ragnarok was able to weave all of that in and deconstruct the gilded image, and much credit to Taika Waititi on really addressing it as extensively as he did without being explicit about it, to the point that it seems to have flown past everyone’s radar.

Thanks, Alphonso, for the great insight. I’ll need to think more about the most recent Thor film.

Love this post. I really like the nothern culture and find very hard to come across good realiable books on the topic here where i live. Thanks for opening my eyes to the modifications done by the movie adaptations.

This was the best that I have read on Marvel content for so long! You amaze me with your insights, thank you for that!

I’m surprised there’s so little love for Marvel’s Thor. Sure, the comics take a lot of liberties with the source material, but curious readers will seek out the more “authentic” sources, so I think the comics are an effective gateway. I know those crappy Hercules cartoons from the 60s started me on my mythology obsession. Olympiaaaaa….

Thanks, Beaa, for the comment.

My understanding is that mythology is constantly being adapted and revised. Even the ancient Greeks were engaged in adaptation and revision, taking ideas from earlier Near Eastern mythologies and reworking them as their own, producing variants of their own myths, and so on. For me, developing a critical view of mythology doesn’t have to mean not having love for mythology. I know that I would much rather read and write about things that really interest me than about things that I simply don’t like.

Regarding “gateway” examples, I think it can go either way. I know people who will probably never get past that horrible Disney musical movie version of Hercules, because that’s all they’ve seen and their interests have moved elsewhere now.

It is different for me as a swede. I’ve grown up with the authentic version. Marvels version was nasty surprise for me later on.

This would be Norse Mythology Marvelized. The story of Thor according to Marvel fits very well into Marvel’s story arc and themes.

Thor is the best of the superheroes by a country mile.

Just as Tom Hiddleston’s Loki is the best baddie!

Awesome critical analysis😀

Am I the only one who loathed Thor? Even for what it is supposed to be -mindless entertainment- it failed to deliver. I have only watched the first movie.

The bits in Asgard were good, but the earth-bound adventure was very thin and sped up. Jane and Thor became romantic couple after one campfire, and the big robot threat was killed after five minutes.

I saw it as a guest at a friend’s house over a holiday- the film imo was a boring lifeless steaming pile of crap. Kat Denning absolutely cannot act and should stick to her series on American tv- ‘Two Broke Girls’

Watch the rest and get back to us.

Whenever I hear about Loki I think of Bill Hicks’ prankster God, placing dinosaur bones in the ground to trick people into not believing in him, then sentencing them to eternal damnation when they reach the pearly gates.

Interesting read.

Great essay. Loved Ragnarok film. My favourite exchange was Loki saying something like “Let’s come to an arrangement” and Hella says, “You sound like him.” Never forget that Odin is as much a schemer and a con man as Loki. He just got better PR.

My favourite parts involve Thor throwing things at Loki to see whether he’s actually there or just projecting his image, and Loki’s expression when Odin praises him for the spell that stripped him of his powers, saying Frigga would have been proud, and says, “I love you, my sons,” because to hear that he’s still loved despite everything he’s done gets to him in a way that no amount of harangue ever could. Bless Tom Hiddleston and his expressive eyes.

I find it very interesting that in Thor: Ragnarok we get a story that is in many ways the dismantling (and ultimately destruction) of a civilization that functions as a parallel to Western-based global superpowers, while the next film in Marvel’s line-up looks set to be a critique of the same Western superpowers, only this time told from the perspective of a demographic on the other side of the imperialist coin.

I finally saw this one, and it may actually be my favorite of the MCU films so far. It has a coherent plot that makes sense and does not require anyone to be plot-stupid, it effectively synthesizes the sci-fi aspects of the MCU with the pseudo-medieval-ish Asgardian aesthetic, it provides villains who make sense and have goals that they act toward, it has great dialog and a good sense of humor without being a mere comedy, there is payoff for franchise-spanning events and character development, and it avoided being preachy while still making a point.

It may have been intended as a critique of imperialism, but in my viewing it was more about hypocrisy than anything else, at least as far as moral lessons go.

There were only really two small quibbles that I had with it: the CGI still isn’t quite up to the sequences where they need fully to animate a humanoid figure, and the thread about Banner’s fear that the Hulk would take over completely was kind of dropped. IIRC the film ends with him in Hulk form on the ship, which bodes ill for Banner.

Oh, one of the things I enjoyed most about the film was how they portrayed Thor once he managed to internalize and access his powers without a focus or limiter (such as mjolnir). I’ve always been a fan of lighting slingers in cRPGs and such, and the visuals in those two scenes were pretty nearly perfect.

I’ve been trying to pinpoint exactly what about the Marvel Versions have totally and completely wrong and why they irk me so much. Unfortunately, I found myself brainwashed by Tumblr and the hordes of Lokeans who base their interpretation of Loki off of Tom Hiddleston (Nothing wrong with the actor, it’s the character that’s incorrect). Loki is NOT the misunderstood anti-hero, only in Marvel-verse. Which doesn’t count b/c it’s so twisted up with Judeo-Christian overtones.

They are entitled to make movies as they want but they shouldn’t be able to cover it as a revamping of the old myths.

Fun reading 🙂

Nicely done!

As a Swede and somewhat educated in Norse mythology (but almost none in the Marvel Universe) I’ve found it very frustrating when my friends (predominately the Americans) make references to the films/characters/events thereof and pass it off as an extension of the mythology. I don’t think they realize how skewed… or just plain inaccurate what they’re reading and viewing is, and perhaps they don’t care. Which is fine, they’re two different things — I just wish they’d stop passing them off as the same, because it often ends up with me going “Huh… but…what? That’s not what happens…” and being labelled as a killjoy when I’m just hearing something different from what I’ve learned. (Gah!)

Fantastic writeup for MCU’s Thor-verse and the Norse mythologies. Spot on.

I like the fact that Thor can sink back a few bevvies inbetween hitting things with his hammer. He’s a Scottish tradesman basically.

Movie’s like Thor require you to suspend disbelief, by this I mean in order to enjoy it you don’t want to think too much about how impossible it all is.

One of the great uses of Norse mythology in SFF is L Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s The Roaring Trumpet, in which the hero projects himself into the world of Norse myth on the eve of Ragnarok. I fondly remember reading this as a teen; it’s a great story.

Great article about a marvellous character. Thank you, James.

This article was extremely comprehensive!

Ragnarok was so disrespectful to the Thor source material. Major tragic events are treated with no gravity at all, and are made into jokes. Nothing matters.

This whole movie is the director deconstructing the Thor franchise and telling us, “Look! Look at how stupid this world is, and how outlandish its characters! Let’s just laugh at it because it’s a silly fantasy, and we don’t take fantasy seriously here. Oh, and Imperialism.”

The film upset me. It represents the bad side of postmodernism that doesn’t just question metanarratives and institutions, but degrades and mocks them without reflection on why they might actually be important.

This was an surprisingly deep analysis into both the Norse mythology of Thor in comparison to the Marvel Universe character that I thoroughly enjoyed, nice work.

I think what makes the Thor films special is that push and pull between Loki and Thor, and Ragnarok really ties their arcs together again in such a great way. Thor essentially goes through what Loki did in the first film, all while confronting that history of racism and imperalism that brought Loki into his family in the first place.

Great historical discussion, and a very interesting consideration of Thor’s changing presentation. Thanks for a great read.

Solidly written piece. I enjoyed reading it, and it was very informative. I learned a few things I did not know, and it made me think about what I did know in a new way. Thank you.

I kind of liked Thor, mainly because the Valhalla-scenes reminded me of Flash Gordon (the movie, that is).

This is a well written and well researched article. It’s an important reminder that everything is written with context and bias. We should not accept that myths have always been interpreted this way, and the current interpretations of Thor have as much to do with modern culture as they do Norse Mythology (if not more.)

A well written, referenced and explanatory article using the approaches of Barthes and Campbell to explain Thor and mythology in comics, children’s books and film. It is true of many American films that the USA is depicted as having the best civil way of life, and that it is the savior of mankind and the planet. This seems to be the trendy theme from many of the American film makers at the moment. On another note, I am interested in myths and legends that is why I read this article. I also believe that Thor is not a new Marvel character, like the others, he has more history and depth. This history and depth is surrounded by the mystery of the unknown combined with the known. Thank you for your insightful views.

Thank you for posting this informative article

A big fan of Thor and loved it.

This was a very in depth essay and I appreciated the way that you compared many different interpretations of Thor and the theme among all of them. I adore the movie Thor and this essay has given me so much more knowledge about the origin of Thor and where the 2011 movie got its inspiration. Thank you!

Very informative and great article! I was surprised to learn Thor did not have to prove himself originally, and even more shocked at the connections you pointed out on how Thor was Americanized in order to change (they are true). It definitely relates to past generations who arrived in the United States and had to adapt in order to “succeed” (e.g., learn a new language, manners, customs, etc.)

Really interesting article! I love looking at the inspiration and messages that directors hide behind phrasing and costume. I’ll definitely have to watch the movie again with this article in mind

This is an insightful analysis of the mythological underpinnings of the film. I was particularly intrigued when the thoughts of this essay arrived at the idea that Thor as a character was symbolically an American figure. What my mind instantly flew to was the scene in “Avengers: Endgame” where Captain America was confirmed equally worthy to wield the hammer of Thor. However, as a character, Captain America seems both very worthy and yet also fairly unworthy of such recognition. Given the succinct description of the worthiness qualifications herein (that is, the trefoil of diplomacy, humility, and self-sacrifice), it is easy to see how Captain America embodies self-sacrifice to the letter. However, his grasp on the other two qualities seems fairly limited. His feud in Civil War hinges on his inability to consider his own failings humbly, and it also exposes his extreme distaste for diplomatic decision-making. This is why, ultimately, it seems as if the power of Mjolnir is most directly linked to self-sacrifice – identifying it as the ultimate attribute of worthiness.

Thank you for writing this! You explain the connections between the traditional mythology and the Marvel mythology in such great detail. I think it is so interesting to discuss what makes someone worthy of Mjolnir and how that concept of worthiness evolved with time.

A comprehensive touch on one of the toughest character in the Marvel Universe. Kudos.

I loved the Thor movie’s take on the Hero’s Journey. At first, it seems like the trip to Jotunheim is the Call to Adventure, but it’s actually Thor’s way of Refusing the true Call to Adventure. It shows he’s not ready for the throne and needs to go on a character-development journey.

Similarly, the Death of the Mentor trope is subverted by Odin coming back from the Odin Sleep at the very end, and the Fighting with my Father trope becomes a drinking contest/bar brawl with Jane’s father figure.