Samuel Beckett’s ‘Film’: Power, Perception, and Paranoia

“Standing on the bare ground, — my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space, — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part and parcel of God. The name of the nearest friend sounds then foreign and accidental: to be brothers, to be acquaintances, master or servant, is then a trifle and a disturbance. I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty. In the wilderness, I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages. In the tranquil landscape, and especially in the distant line of the horizon, man beholds somewhat as beautiful as his own nature.” Ralph Waldo Emerson,“Nature” (1836)

The above excerpt from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Nature” presents an ideal that Buster Keaton’s character in Samuel Beckett’s Film (1965) cannot achieve. In opposition to Emerson’s transcendental idealism, Beckett’s avant-garde film suggests that human beings can never escape the confines of the intruding eyeball, and they can never eradicate the boundaries of judgment and fear.

Film stars Keaton as an everyman who goes through his day as if he is being judged, stared at, and invaded. He seeks refuge in his vacant apartment, shielding himself from anything that resembles an eyeball. This includes any eyes on a wall illustration and those of a puppy, a kitten, a parrot, a gold fish, and inanimate objects like an envelope and a chain.

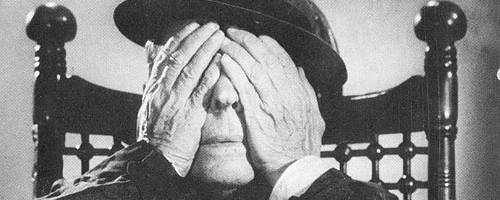

We never see the face of Keaton’s character until the very end when it is captured by the camera in a full close-up. Keaton’s character has finally escaped the judgmental looks of others (or things), but he cannot hide from his perception of himself, and this is visually illustrated in the final moments when he stares at a version of himself and subsequently covers his eyes in fear. It’s this gaze that haunts the individual forever, Beckett implies. In solitude, there is no tranquility to be found, and this counters the transcendentalists who believe that people can achieve a spiritual awakening when they’re alone.

On the one hand, Beckett suggests that the eyeball communicates to its subject, and its subject perceives this communication to be negative, thereby giving rise to feelings of judgment, invasion, fear, and shame. Notice the scene early in the film when Keaton’s character bumps into two strangers on the street, and they stare at him as if he’s a creature from another planet. This, of course, causes Keaton’s character to return to his apartment.

On the other hand, Beckett shows that human beings can never escape these feelings of judgment, invasion, fear, and shame because they always have to come to terms with their perception of themselves. The final scene that I discuss above demonstrates this, as Keaton’s character encounters who he is and cannot bear it. Even in seclusion, Beckett claims, individuals have to look at themselves and they might not like what they see.

So much of cinema studies scholarship focuses on visual perception with an emphasis on the gaze and the power dynamics between the one who looks and the one who is looked at. Beckett’s Film is significant, then, because it forces us to consider what happens when the one who looks and the one who is looked at are the same person. In addition, Beckett asks us to confront issues of technology, surveillance, and privacy that are especially relevant today.

Film was released before the advent of social media and the internet, but in many ways it speaks to the fears of contemporary digital culture. Is there such a thing as privacy anymore, and if so, how do we obtain it? Beckett investigates the power of perception and paranoia, and it’s appropriate to assume that many individuals today fear that they are constantly being looked at in private spaces, just as Keaton’s character does.

Unlike Keaton’s character, however, who is afraid of the quiet, private moments in which he must face himself, individuals today are more likely to be concerned with others who might be watching. The leaked private recordings of Justin Bieber and Donald Sterling, as well as the “Fappening” scandal, should give us pause, at the very least, that the distinction between public and private isn’t as easily made today. Surveillance technology has made it simpler for institutions to monitor our every move, and what might be intended as an innocent textual conversation between two people quickly becomes fodder for the public gossip mills. Everything we say and do, indeed, can be used against us.

Like most avant-garde cinema, Film is self-reflexive in the sense that it calls attention to the cinematic apparatus. The cinematic experience is inherently voyeuristic, and much of its magic derives from the pleasure of gazing at people in a darkened movie theater. Some scholars like Laura Mulvey have been critical of this scopophilia, or love of looking, and Beckett is fearful of it as well. Not only does Beckett challenge us to consider why we love to look–to be voyeurs–he forces us to question how we’d react if the camera was turned on us.

Film isn’t the only cinematic work to criticize the medium. Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) and Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) demonstrate the dangers of voyeurism, and remain to this day fascinating psychological thrillers. However, Film stands out for taking things a step further. Whereas the former films always show us who the voyeurs are, the latter leaves us in the dark. In this regard, Film has much in common with Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), which directly taps into the paranoia of post-Watergate America.

This paranoia, I argue, has only increased over the years. Corporations are in control, but few of us know who the leaders are. We store our information on services like Dropbox or the iCloud assuming that we’ll be protected, but an anonymous authority figure has access to our data. It’s best to look the other way and assume that everything will be okay. However, another headline-grabbing leak occurs to remind us that we’re always at risk.

In a perfect world, we’d love to simply live off of the internet and do things the old fashioned way, but as institutions require us to have an online presence, this becomes more difficult. Most of us need to exchange information online for school or work, and many of us take advantage of the seemingly convenient online banking system. I’ve never been one for conspiracy theories, but I can’t help but take a step back and wonder why we’ve all just accepted this without considering how the powerful institutions may benefit when it all comes crashing down.

The power of Beckett’s prophetic film after nearly 50 years is the literal realization of the character’s fears in the 21st century. Today, many of us similarly believe that someone somewhere is invading our privacy and watching us, and it’s discomforting to know that someone somewhere probably is.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Anyone who puts any personal data in the cloud has lost there ability to reason.

Considering that the Government and Banking industry as well as the Retail sector is an open book to hackers and believing some hype about the convenience and security of storing your personal data on someone elses server is as close to a con job as you can get.

Very current topic, great read.

I liked FILM very much. There’s one thing, though, that I find unclear. “To be is to be perceived”, and Keaton’s character is avoiding perception, so it seems that he wishes he didn’t exist. But paradoxically, it’s this perception that kills him (or maybe at least defeats him. But it sure does kill the old woman). So, was he actually trying to save his existence, not escape it..?

Excellent analysis.

If the NSA came out and said that they were no longer spying on the average citizen and were going back to following the constitution, would you believe them?

Wonderful analysis of our Panopticon digital culture, and the way in which the gaze has been inculcated as the primary mode of control over our social and psychological lives. A very pertinent topic, and a very foreboding thought that for all our technological advances, humanity has relinquished the human capacity for solitary contentment as Emerson so beautifully wrote about. Great analysis!

People blame Apple and other companies but the truth is that most people lack computer knowledge. The first rule of computer security is that you do not put online something that can’t go public. No matter how strong the security system is it always can be broken. it can take weeks or months but it eventually will. Neither IT companies nor the stars should be blamed for this. This is the “hacker” fault.

Interesting little film.

The problem when State Security spies on all the citizens is that they could hear or read some off-handed comment and believe it is representative of an anti-state sentiment.

Absolutely interesting to read, very important issue to discuss and most debacle issue in united states as well as in world.

“Those willing to give up liberty for security deserve neither and will lose both.”

— Benjamin Franklin

Anyone interested to watch this one can do so here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZtV-iHeQd0

Big lesson on the privacy of the “cloud”. Apple: Oopsie, we had a vulnerability. All systems have vulnerability. Don’t put anything on the cloud you don’t want many others to see.

The government needs to be brought back to reality. They work for us. We do not work for them. This is the only institution I know of where the employee rules the employer. This needs to change.

The omniscient eye, it always seemed to me, was that of the camera and by extrapolation everyone in any viewing audience. This universalizes the eye.

What Keaton and all the actors fear is the eye of indifference, given that any viewer and any actor would never come to know one another personally. The two strangers, for example (see above) are shocked and horrified not at Keaton, but at their realization he personifies awareness of this human indifference: it is again the theater audience who stares back into their world which can only have a scripted two-dimensionality as it is a world portrayed under deceptive light and props at the same time. (Why it has the title it does.) At least, that is how it seems to me. The real danger may not be lack of solace due to an inability to face the grandeur of Nature, but the danger of mistaking the vicarious with reality altogether. In the end Buster discovers that he can only see himself as others see him as his solitary self-definition: he is condemned to a forlorn narcissism as solitary meaning for his existence. He can never become part of the audience, the world that is real.

The social qua political commentary at the end of the article asks the important question of “why we have just all accepted this.” The answer is that it permits each of us to be a legend in one’s own mind, in spite of the indifference of a cosmos that could never be our spectator, or audience.

Anyone have any clue as to how to stop our governments doing whatever the hell they like. I’m fed up with it.

Wow, I didn’t even know Beckett made a film. I have to check this out!

Big Brother is out there. George Orwell had it right. I think my paranoia is getting the best of me.

Paranoia is a fear based on falsities. Now we all know that they have our “data” stored somewhere, so a fear that what we do on the internet is a fear based in facts, not falsities, so for cpeel150, it is not your paranoia, this is really happening, as hard as it is to come by. Many believe the corporations themselves constructed the lines to conduct such powerful, mass communication technologies in the world but how does a start up comms company have enough money or clearance to build lines across countries and waters? It’s obvious that the government had a huge hand in the creation of such systems and you had better believe they have more planned, why wouldn’t they monitor everything, they own it. Do we not have a right to monitor what we own? Of course not, so if one is not content with the fact that while using someone else’s technology they’re data is being collected (possibly for the efficiency) then don’t use it, as impossible as that sounds. We write as if we own or have a right to use the internet; imagine how living was before the internet and then take a look at the sliver of time we as humans have access to SUCH overwhelming stimulation, something is definitely “going on”. The only power we have is to use this resource wisely, without becoming dependent on it; that’s what gives them the most power (over us)!

Beckett’s ‘Film’ resonates with me because it is a fine portrayal of self-consciousness. The paranoia in Beckett’s ‘Film’ seems to be a little different than 21st century paranoia due to technological surveillance, since while Keaton avoids the gaze in his home or outside, a lot of people avidly seek the public’s attention, but only not in the privacy of their own homes.

Fantastic photos. It’s great to read this work on FILM. The concept of the “intruding eyeball” is pertinent but also warrants returning to the text. I believe FILM is collected in I CAN’T GO ON. I’LL GO ON. The reason I mention this is that the “camera,” the electronic embodiment of this “intruding eyeball,” in that collection, is referred to as if ‘it’, or ‘he’, were a character. Lots of new ground for Beckett and visualization.

“… Beckett’s avant-garde film suggests that human beings can never escape the confines of the intruding eyeball, and they can never eradicate the boundaries of judgment and fear.”

This was very much a concern among the common man amongst each other in the 50s and 60s.