World War One: Truth Within Artistic Representations

World War One within a historic context has been reflected upon as a noble struggle for democracy. This has led to World War One being depicted within various creative mediums, wherever it be art, cinema, fictional novels or television, as a noble cause. However, there was and has been opposing creative representations of World War One, depicting a horrific reality. Thomas W. Gaehtgens notes that “the propaganistic campaigns supported and perhaps even inspired the naive enthusiasm and ardent feelings of patriotism that motivated many volunteers to enlist” [1]. Yet artists who personally experienced World War One through trenches and military hospitals felt an urge to reveal the truth, rather than accept deception portrayed in official war propaganda.

Stanley Spencer: War and Emotional Trauma

Stanley Spencer served in the Royal Army Medical Corps and as an orderly at Beaufort Hospital, which was a psychiatric ward for wounded soldiers during World War One. World War One had a profound affect upon Spencer’s psyche, stating “I value the experience and I feel quite sure, long sure I have seen the result” [2]. Spencer’s war experiences, which was significant upon his psyche, caused his creative output to express trauma. Dug-Out (Stand-to) reflects a sense of impending doom upon soldiers preparing in their trenches. The painting’s composition makes viewers contemplate war’s psychological toll. The foreground shows a group of soldiers preparing equipment in their trench, most likely for an emerging battle. The soldiers’ expressions and physical appearance reflects their hardship. Each soldier seems out of his depth, simply following orders but not having confidence in their actions. The solider central in the foreground, most likely head of the group, looks over to his comrade with a helpless look. Dug-Out (Stand-to) emphasises that war’s preparation is physiologically damaging. The soldiers’ fragile psychological state is further conveyed by barb wire consuming the background. The barb wire blackens its atmosphere, thus helping viewers to emote with the soldiers’ inescapable fear.

Tea in the Hospital Ward, while more subtle compared to Dug-out (Stand-to), is no less powerful in expressing emotional agony. Tea in the Hospital Ward depicts a Beaufort Hospital scene, where patients were in the process of recovery. Spencer’s choice of scene in comparison to the patients’ emotional state is profound. The faces of patients shown are weary. The patient reaching for bread with his pale skin looks dejected, while another patient sat in the forefront is possibly contemplating war’s horrors. Spencer’s experience with Beaufort Hospital patients meant he could understand them, who as soldiers were typically seen as pinnacles of strength, when in fact they were human beings deeply affected by what had been required of them. The patients in bed, either too tired or indifferent to take food and beverages, further reflects the psychological toll of soldiers who were seen as undiminished heroes.

C.R.W. Nevinson: War and Destruction

C.R.W. Nevinson served in the Friends’ Ambulance Unit and Royal Army Medical Corps, psychologically affected by his work tending to the wounded. Nevinson expressed his experiences through Futurist and Cubist aesthetics, both of which emphasise how shapes and spaces can be explored and understood in abstract terms. Nevinson felt his artistic style was “the only possible medium to express the crudeness, violence and brutality of the emotions seen and felt on the present battlefields of Europe” [3]. Explosion conveys Nevinson’s sentiments. The bleak landscape is overwhelmed by a huge explosion, its impact upon the earth causing devastation to what was once a peaceful landscape. Explosion showing the exact moment of an impact allows viewers to engage with abstract ideas as to the immediate aftermath. The death, devastation and decay which followed this explosion conveys a tragic truth in wartime.

A Howitzer Gun in Elevation continues Nevinson’s sentiment of war’s brutality, showing warring nations’ commitment to destruction. The composition is dominated by a Howitzer Gun, with its threatening stance and dark color, waiting to cause destruction. Nevinson’s use of composition once again ignites abstract thoughts, viewers can imagine the devastation which will be caused. The clear skyline acting as a contrast further emphaises abstract thoughts of Howitzer Gun as a menacing weapon, where nature’s purity will soon be destroyed by war’s immoral strength.

Henry Tonks: War’s Tragic Reality

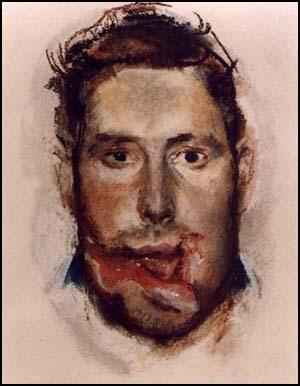

Henry Tonks’ most striking work during World War One was his series of pastel drawings, observing wounded soldiers receiving facial reconstruction at Cambridge Military Hospital and Queen’s Hospital. The uncompromising realism of Tonks’ pastel drawings is prominent in understanding the extent in which soldiers sacrificed themselves, far from the naive heroism represented in official war propaganda. Tonks felt that “the painter who is not a poet ought to be put in the stocks” [4], reflecting Tonks’ need to emote towards viewers observing his art. Portrait of a Wounded Soldier before Treatment‘s close-up composition engages the viewer with intimacy. The close-up composition forces detailed analysis of the soldier’s horrific wound. Tonks’ use of a realistic aesthetic leaves no doubt in a viewer’s observations to the cost of war. This intimacy can never fail to be emotive.

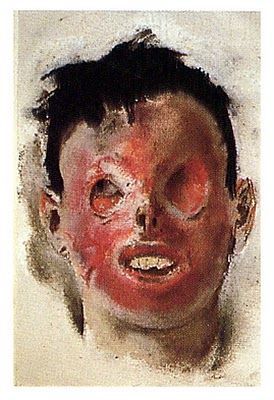

Second Portrait of a Wounded Soldier before Treatment, like its contemporary piece, uses a close-up composition to engage the viewer’s intimate observations. Second Portrait of a Wounded Soldier before Treatment is, without taking away from the facial injuries of its contemporary piece, even more horrifying to observe. This soldier’s extensive injuries makes him barely recognisable as a human being, especially his mutilated eyes and nose. Tonks’ use of a realistic aesthetic once again leaves no doubt that a viewer can be emotive in their observations to this soldier’s sacrifice.

Spencer, Nevinson and Tonks’ artistic representations gave credence to the notion that official World War One propaganda was contradictory to its horrific reality. These artists who experienced war first hand, rather than be commissioned to portray heroic acts in the name of patriotism, knew the physical and physiological effects of war. Their creative output expresses an understanding of war’s brutality, that any notion of national pride was quickly diminished and soldiers become demoralised through horror and destruction.

Works Cited

1. Gaehtgens., T.W. 2014. ‘Introduction’. G. Hughes and P. Blom, eds. 2014. Nothing but the Clouds Unchanged: Artists in World War I. Getty Publications. 2014. pp. 1-4.

2. Bowker., J.W. 2007. The Sacred Neuron: Discovering the Extraordinary Links Between Science and Religion. I.B. Tauris & Co Limited.

3. Haycock., D.B. A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War. Old Street Publishing.

4. Chilvers., I and Glaves-Smith., J. 2009. A Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Thank you for this interesting information on WWI art, I appreciate your research. Regarding Spencer’s Dug Out the shape of the painting gives me the impression of a casket or coffin especially with the digging of the trenches. Both works by Nevinson I see phallic symbolism. Tonks pastels of the pre- reconstruction surgery is important and gives the viewer the opportunity to see the affects of war on a human. I really appreciate this information.

Thank you Venus. You raise an interesting observation regarding Dug-Out (Stand-To) representing coffin/grave symbolism. Not a thought which had crossed my mind.

Interesting piece. Some painting I’ve never seen before… thanks for this. Also made me think of Ernest Hemingway… another artist who depicted ‘the truth’ about the war, albeit through literature.

Thanks for the comments Matt

Henry Tonks’ pastel portraits of soldiers are lovely.

I used to love to cycle over to the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham. I enjoyed the unusual perspective in his paintings. Salvador Dali’s ‘Christ of St John on the Cross’ had the same fascination. Art was in a very good place then.

I love Cookham by Stanley Spencer.

I love seeing artistic repetitions from this time period. My favorite is Henry Tonks first portrait of a wounded solider before surgery because the pastel style of drawing is very expressive.

C.R.W. Nevinson was England’s only Futurist

Spencer was a wonderful artist of enormous talent.

There are in the world of the arts over the last two millennia been a small number of transcending geniuses. Beethoven, Bach, Mozart in music, for example; Giotto, Botticelli, Michelangelo in painting.

Stanley Spencer, whose work I have always admired greatly, does not reach that small group.

Art is a subjective concept. So what some may find fascinating, others may find inadequate

These document the gruelling routine of military.

I wasn’t familiar with Spencer. Emotional art as reaction to war experiences reminds of Kirchner’s work. Aesthetically different but has a strong emotional resonance.

Nevinson was among the most interesting of British artists.

This is a very interesting article Ryan. I just finished taking a class in World War I literature, but the only art work that I saw was from Otto Dix, so it’s great to learn about these other artists and how their work helped to show others how terrible that war was. I’ll be sure to look into them some more.

Thanks for the comment. Did you look at Wilfred Owen at all during your WW1 Literature class? Some of his poems dealt with the fatality of serving in no man’s land.

Wonderful stuff.

The set of World War II paintings of shipyards on the Clyde is superior.

Just beautiful.

This is an excellent point, not only does the type of art produced during this time period reflect the socio-political perspectives of a global society, it also reveals the effects this imagery had upon the public. Perhaps the reason for the focus on the artwork that represents WWI as a heroic effort for democracy because it was the justification people needed at that time to rationalize such horrific acts committed on humans by humans.

In addition, the artwork presents itself as an outlet for the troubled mind, as in the case of Spencer. Until recently, little attention has been paid to psychological effects upon soldiers. This particular artwork gives a small insight into the significant toll global events had upon this individual and the life-long damage war perpetuates. Spencer may have been more fortunate because he was able to express his demons creatively, to share them with others and alleviate some of the weight upon his shoulders.

Similarly to the case with Nevinson, in the crucial quote you intelligently added; the artist expresses a significant point about ones’ ability to communicate traumatic experiences. In many cases, words cannot even begin to relate the amount of pain and suffering that a powerful image can. Hence Barnard’s famous and valid quote, “a picture is worth a thousand words.”

The mention of Tonks was certainly an impactful example. I have viewed plenty of photographs depicting this subject matter, but the expressive quality in the lines and corporeal application of color of Tonks’ pastels absolutely accentuates the emotion you so articulately discuss. While the photographs carry a hyper-realistic quality, sometimes the realistic horror of those photographs eclipses the emotive qualities. However, painting, coupled with personal expression, has the ability to invoke compassion and empathy.

Thank you for this outstanding contribution. The artwork was very striking and your comments were equally powerful.

The Spencer pieces very much reflect the mood of the Western world toward war in this time (late 20s-early 30s). See, e.g., Wings (1926).