Is Fiddler on the Roof a Tragedy? An Aristotelian Analysis

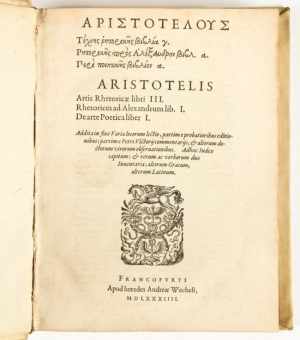

Considering the twistings and ambiguities rife in modern genre, the attempt to classify modern works of fiction into strict genres, as could be done more easily in the past, rapidly inspires a vague notion of futility in those who attempt it (just open iTunes and skim the myriad of musical genres to get a sense of this disintegration). Can the classical accounts of genre, as expounded in the most influential treatise on genre, Aristotle’s Poetics, still have any relevance in classifying and understanding contemporary works of imagination? Can his strict categories still provide any clarification for a work of fiction, or has it become a hopelessly antiquated work of a different time with different sorts of entertainments? Though few popular works fit into Aristotle’s clear and organized study of the best sort of storytelling, nevertheless his work can illuminate a more modern work in surprising and compelling ways. To illustrate our case, we shall apply Aristotle’s criteria to a popular musical of ambiguous genre: Fiddler on the Roof.

Models from the Past

Now, perhaps it is a bit incongruous to apply the writings of a thinker of such lofty status as Aristotle to popular entertainment such as the modern musical: but Aristotle himself doubtless would have no such compunctions. He never judged the artistic merit of a piece without applying to it his carefully considered criteria, and we shall honor his method and do the same. First, we must inquire, when Aristotle uses the term “tragedy,” what, specifically, does he mean? As it happens, he defines it quite clearly in the Poetics, stating that a tragedy is “the imitation of an action that is serious and also, as having magnitude, complete in itself…in a dramatic, not a narrative form; with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions.”

Now, as with anything in Aristotle, this seemingly simple definition is densely packed with meaning and potential for all manner of interpretations (let’s not even begin tackling “catharsis”). Nevertheless, on the most basic level, Aristotle’s definition can be understood to mean a dramatic form displaying a unified, complete action, the content of which inspires pity in the one who witnesses it, with the view of somehow purging the excess of these emotions. Probably at least ten different people, scholars and amateurs alike, will rise up and take issue with my take on his definition. But it seems clear that, for Aristotle, tragedy serves an important function in the moral life, allowing us, in a controlled situation, to purge negative sorts of emotion that might impede our ability to act in a rational and virtuous manner.

In his treatise, Aristotle begins with the one integral, but often overlooked element of a work of fiction: the plot. And, for his analysis of the perfect tragic plot, he gives us four essential elements: 1) It “must have a single, and not a double issue.” That is, the plot must center on one central, overarching problem, rather than a fragmentation of tiny, diverse problems. 2) “The change in the hero’s fortune” must go from “happiness to misery,” rather than misery to happiness. Self-evident, considering this is tragedy of which we speak. 3) The cause must lie in some”great error on his part,” not in any “depravity.” For, if the cause lay in his depravity, he garners no sympathy from the audience, thus rendering the tragedy pointless. 4) “The man himself being such as we have described, or better, not worse than that,” since, again, a bad man fails to inspire any real sympathy.

For Aristotle, the primary purpose of a tragedy is to inspire “pity and fear” in those who witness it (a phrase subject to endless philosophical and literary debate which shall leave aside for our purposes). Indeed, “the Plot in fact should be so framed that, even without seeing the things that take place, he who simply hears the account of them should be filled with horror and pity at the incidents.” One need not see Oedipus the King to recoil in horror at the infamous denouement; one need not see Chinatown to appreciate its horrific and bleak conclusion.

The last two elements of Aristotle’s treatment relevant to our discussion are what he calls “peripeties” and “discoveries.” Peripety “is the change of the kind described from one state of things within the play to its opposite…in the probable or necessary sequence of events.” That is, the shift in fortune for the tragic hero must bring him from a state of relative peace and good order, to one of turmoil and chaos, and it must be intelligible within the framework of the play. A deus ex machina is distinctly inartistic. Discovery, as defined here, is a “change from ignorance to knowledge.” While Aristotle’s definition may sound stupidly obvious, its significance for the tragedy is that this change usually uncovers something the hero would much prefer had been kept hidden, as when Oedipus discovers he murdered his father and married his mother.

Indeed, one might say that the discovery occasions the peripety: to use the unfortunate Theban once more, if Oedipus had not endeavored to discover his true parentage, had not sought to exchange his ignorance with knowledge, his fortunes would never have been devastated so spectacularly and he would have remained the king of a prosperous and orderly Thebes, albeit married to his own mother all the while. Simple as they may seem, peripety and discovery are vital elements for a proper tragedy: if they are not executed with skill, the subsequent tragedy will lack something conspicuously.

Contemporary Problems

All well and good, but how do these criteria for an antiquated form of theatre apply to a modern work of a modern medium, that of musical theatre? To begin, we must consider the plot of Fiddler on the Roof on its most basic level. Most simply, it tells the story of an impoverished Jewish milkman, Reb Tevye, whose daughters all find themselves married in nontraditional ways, against the backdrop of growing social unrest that eventually forces them from their home. By the bare relation of these sparse details, we can see Fiddler fits into many of the basic essentials set down by Aristotle, except in one, perhaps crucial, particular: the events described indeed inspire pity, but fear? Is there anything inherently fearful or horrifying arising from the plot of this musical comedy/drama? That is the crux question of our analysis.

There are three primary peripeties of Fiddler, all of them centering upon the choice of husband made by Tevye’s oldest daughters. The first to break with the revered traditions, the break that defines the events of the musical as a whole, are his eldest Tzeitel and her childhood friend, Motel; rather than accepting the match Tevye has arranged with the wealthy, middle-aged butcher, Lazar Wolf, she pleads with Tevye not to make her marry him. Faced with the unexpected resilience of his daughter’s beloved, Tevye relents and lets them have their way. But that is not the peripety with which we are concerned. Rather, an “unofficial demonstration”—a pogrom—disrupts the reception, ending a joyous occasion in violence and sullen acquiescence.

The story of Tzeitel and Motel, of all the daughters’ courtships, resembles most the classical model of a comedy. The two begin courting in secret, wishing to wed but not daring to breathe a word of it, for such an intention would be an audacious break with the implacable tradition, but, through an impassioned confrontation with Tevye, achieve the cherished goal they never dared hope to realize. And while their story ends happily for the nuptials, the violent disruption of those nuptials presages the ominous developments for the characters as the plot rolls along.

The second break comes when his second eldest, Hodel, and her Marxist fiancé, Perchik, decide to wed—though, when they decide to inform Tevye, the request is for his blessing rather than his permission. Not without much interior turmoil, Tevye relents with both his blessing and his permission. However, the burgeoning strife leads to Perchik’s arrest and exile, and, in a rather uncharacteristic turn, Hodel elects to join her beloved in exile. While something of a reversal, in this instance it lacks the shock value present in Tzeitel and Motel’s courtship.

Since we knew Hodel and Perchik had taken a shine to each other, their ensuing desire to wed comes as expected. Likewise, as Perchik never took great pains to hide his radical politics, his arrest does not spring up from nowhere either. Indeed, the greatest surprise of this episode (though gentle compared to what follows) may be Hodel’s new-found selflessness. Having heretofore cared for little more than finding a rich husband, she is willing to sacrifice everything she knew and loved in order to join her beloved in poverty and exile in the service of something larger than herself. Justifiably, the middle reversal carries less weight and much less surprise than the instance of the previous daughter. The same cannot be said, however, for the choice of spouse made by Tevye’s third child.

For the third break, that of Chava and the Russian Christian Fyedka, constitutes perhaps the most shocking moment of the entire show. Indeed, the scandal is so great, the audacity of the action an affront to every belief Tevye most cherishes, no amount of pleading, begging, or even filial love can induce him to accept Chava and Fyedka. Appropriately, the final reversal is seemingly just as irreversible and unacceptable. The tumultuous outside tensions culminate such that the Russian government forces the Jews out of Anatevka, their home, forever.

This turn of events is the one most purely belonging to the realm of “tragedy” as defined by Aristotle. Chava, “everybody’s favorite child,” kept to herself and her books, “gentle, kind and affectionate,” certainly the last girl any of the Jews of Anatevka would expect to flaunt tradition for a man with such appalling ease. And, with the banishment of the Jews, though there was some tension at the outset, we received little indication events would turn out as disastrously for the Jews as they did. Though one can see the groundwork being laid for this development as the plot unfolds, it still strikes one as disturbing and brutally unfair, though the characters can do nothing to remedy it.

Reconciliation?

To those who have not had the pleasure of witnessing it, the musical appears to end on a bleak note of helplessness. But those who see the play know, that, despite the downbeat conclusion and piteous elements, not all is somber resignation, but instead, shot through with moments of hope—and indeed, the play is actually quite funny. Then, how does the story fit within Aristotle’s general framework, if it appears to concede to either pure tragedy or pure comedy?

The basic storyline operates on two levels: the first, which we shall call the “A-story,” follows the saga of Tevye and his daughters. The second, distinct though interwoven in the main action, the “B-story” would be the plight of the Jews as a marginalized community at the edge of an indifferent empire in the throes of burgeoning political agitation. And something intriguing emerges if we analyze each level separately. The A-story of Tevye and his daughters ends much like a comedy, in the classical sense: that is, it begins in disunity and ends in unity. The daughters have less than hopeless prospects, belonging to a poor family, yet, at the conclusion, all of them are not only married, but married to the man of their first choice. The B-story, that of the plight of the Jews of Anatevka, begins with relative concord between the Christians and Jews of Anatevka, but the situation completely unravels, ending with the banishment of the Jews. In that sense, the B-story ends more like a traditional tragedy. On the one hand, the girls’ bleak prospects are resolved by happy, though unconventional marriages; on the other, the tensions give way to violence and exile for the community as a whole.

How can reconciliation be achieved among these seemingly conflicting elements? Obviously, Fiddler is neither a tragedy, nor a straight comedy in either the strict classical sense or the looser modern sense. By combining both elements, it makes for a bittersweet, rather than purely happy or tragic, conclusion. Though the external circumstances of Tevye’s family have been reduced beyond what they heretofore had considered possible, the reconciliation of their internal affairs end the show on a decidedly hopeful note. Tzeitel and Motel promise to rejoin the family as soon as their financial situation allow; Hodel and Perchik live blissfully together in Siberia; and, at the bitter end, when Chava and Fyedka come to give their support and farewells, Tevye bids them a simple “God be with you.”

So, while neither a tragedy nor a comedy, strictly speaking, Fiddler combines elements of both to make for a bittersweet conclusion. It ends tragically in that the circumstances of Tevye’s family has unraveled hopelessly beyond his control. But the internal circumstances of Tevye’s family, his relationships with his daughters, have been healed and perhaps strengthened. He knows and understands his daughters better than he had before, sacrificing the rules of “tradition” in favor of giving them the husbands of their choice.

Fiddler is by no means the first work of fiction to combine apparently conflicting elements of diverse genres. Dante himself broke new ground by taking what was before considered a ‘Low’ genre—the Comedy—and gave it the ‘High” purposes reserved for Tragedy: hence, the Divina Commedia. In this case though, the tragic and comic are combined to create this hilarious but poignant tale of the plight of the Jews at the turn of the century, but, most significantly, illustrating the story of a simple milkman who wants to raise his daughters as women of God, in the face of a rapidly collapsing, beloved way of life. Thus, Fiddler on the Roof, while tragic on one level and comic on the other, does not belong wholly to either genre. However, it is the elements of hope that predominate. What could have been the tragic tale describing the crushing blow of fate instead provides an exemplar of the indomitable human spirit: though we may not all have the ability to rise up against the injustice of our particular situation, at the very least we may not go out without a laugh.

Works Cited

Aristotle, Poetics, translated by Ingram Bywater, from The Basic Works of Aristotle, edited by. Richard McKeon (New York, New York: Modern Library Classics, 2001).

Fiddler on the Roof, music by Jerry Block, lyrics by Sheldon Harnick, book by Joseph Stein, 1964.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I love the rebelliousness of this play: the overthrowing of tradition.

This musical is very near and dear to my heart. It was my first show that I ever did when I was 11 and played the part of Tevye’s fourth daughter, Shprintze. Ten years later, I auditioned again and got to play the part of Hodel, Tevye’s second daughter. This is such a beautiful story.

Truly a remarkable, memorable classic.

As an instructor, I approve of this analysis. I am very excited to tackle this wonderful classic! So far my students are loving it as well. They are amazing! Thanks for the read.

A very sound analysis of one of the most popular theatrical musicals of the twentieth century. While I happen to disagree with your contention that “Fiddler” qualifies as a tragedy under Aristotle’s definition, I concede that your basic points are very well argued.

What a great study. Thank you for this piece.

This is a very popular choice for school and community productions.

If you want to make a life performing in musical theater, this is your bible.

I read the book not long ago and I recently found out that Joseph Stein passed away, but reading his story I became aware of how many of his writings I had read. A wonderful author with that gift of explaining people and places to our complete under standing.

Great Script, Great Musical, Great Article.

I really need to catch this in a theater soon!

Still the only musical I will seek out to see a production of.

Involved with this one in college!

Fantastic analysis and a fascinating story.

I know each song in this one and found myself humming each song while reading this. How strange!

One of the best story lines for a musical.

enjoyed the book; loved the movie, adored the play.

This is a wonderful story, with some real history to it. Thanks for the analysis.

I absolutely LOVE this musical! Being in the cast is such a remarkable experience!

The Stetl society is held together and its families are held together by a combination of beliefs and the traditions that have sprung up around them. As the traditions are chalenged by the daughters we see a parallel to the changes of the larger society a the beginning of the twentieth century. However, this “faith” and tradition (and faith IN tradition) is the viscera that holds the body politique and the family together. Tearing oneself away from that viscera has serious consequences on the psyche, relationships and functioning.As a musical, Fiddler is forgiven for leaving us such romantic idealism. I’d love it if there were a sequel.

It’s fun to see how traditions change so dramatically and to see how they can change.

The music is really good.

Always find these studies welcome! I loved the movie and I’ve seen the play.

I agree with your description of Fiddler as bittersweet. I do not feel like it conforms to Aristotle’s rules of tragedy. The play is filled with growth and change, which is hard for the characters, but always ends with hope. Even the final scene, which depicts families leaving the home they love, is acted with groups of people supporting and lifting one another.

Fiddler is becoming more and more relevant in the society of today, where the traditional family is becoming a fluid term. As young adults prepare to enter the world, they are making choices that often challenge the way their parents raised them. As a parent, my goal is to take the choices with a level of hope and optimism that is demonstrated in Fiddler.

I imagine Aristotle enjoying Fiddler on the Roof (and having as much fun as you did working through this question).

Intriguing analysis. You hit it on the head when you say, “How do these criteria for an antiquated form of theatre apply to a modern work of a modern medium, that of musical theatre?” That’s the soul of this argument: part of the struggle you land on is an effort to situate it within two historical — and indeed multiple cultural — periods, which each inherently informs how you perceive the play.

Aristotle’s framework automatically assumes a subjective analysis: “…with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions”. The problem is, the stimuli that induce pity or fear vary with time, individual, and place. And this gets to your point about identifying the fear in the play. If you were an audience member watching Fiddler on the Roof in its debut in the 1960s, the cultural and political norms might well have placed it as a tragedy, and someone watching from an older generation might commonly end the story with a sense of despair and nostalgia; it seemed full of acts of rebellion.

In today’s context in the US at least, we’re viewing it within a society pushing more and more for progressive norms. Tevye becomes this beautiful persona of someone with deep principles and ideals, yet who ultimately does right by his daughters — something Western society generally celebrates now. Take the discussion into different cultures or ages, and of course, the answers will differ even more vastly.

Aristotle’s definition really does assume a subjective reality — but that’s what makes the discussion so fascinating. What is comedy for one becomes tragedy for another, because every part of your individual experience feeds in and informs how you see the play. And that’s, perhaps, why Fiddler is so remarkedly persistent through time — its complexity allows for the full range of emotions, and doesn’t try to classify itself as one or the other.

Thanks for the insightful commentary — definitely made me think!

The example of browsing iTunes for examples of untidy genre classification accurately summarizes “Fiddler on the Roof’s” categorical crisis. The story is an epic in a sense time narrates what is gained and learned in sorrow. Epics cover a vast range of typical genres such as westerns and historical dramas among other “odyssey”-oriented tales. By applying and paralleling the context of Aristotle’s Poetics to “Fiddler,” this article successfully educates and informs admirers of the beloved musical on the historical depth and universality of its thematic elements.

This is one of my favourite musicals and as I am studying Aristotle’s poetics as part of my English Degree, this was a really useful analysis. Regarding fear -my understanding is Aristotle says it is aroused by the misfortune of a man like ourselves, ideally brought about by his own actions. Which parent would not associate with Tevye and his concerns about his children making the right choice of partner. His life can be seen as that of any loving parent with children who have been brought up with boundaries and seek approval. So the fear is watching that which all hold dear being broken apart and realising that it could happen to us. It is true that political circumstances were beyond his control – but perhaps at some level it makes us think about the conflict between adhering to our religious convictions and complying with an extremist government in order to survive. Quite frightening.

Really enjoyed your analysis in this article. I do believe Fiddler on the Roof fits into the tragedy category, but like any real life tragedy, it is often shaded with moments of hope and even happiness. The ambiguity is part of the charm and poignancy of the musical, in my opinion.

I saw a performance of Fiddler for the first time a few months ago. I was pleasantly surprised and really enjoyed it. I agree that it has quite the bittersweet ending.

I loved that movie, and still do. However, I view the turmoil and conflict Tevye has with his daughters as universal & timeless. Every father faces similar dilemmas when their daughters seek a mate. He’s not good enough, a bum, but she loves him . . .

This is very much more of a child from the theatre from the 17th to the 19th Centuries, where elements of tragedy and comedy were fused in one play, regardless of whether the play was a comedy or a tragedy.