Akira: An Analysis of the A-Bomb and Japanese Animation

The cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were bombed on August 6th and 9th, 1945, respectively. The first use of the atomic bomb on a highly populated area would come to embed itself in the cultural psyche of the Japanese public for years to come, and is often cited as an inspiration for numerous popular manga and anime. A few of the most notable works of these include Keiji Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen (1983) and Isao Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies (1988). As scholar Susan J. Napier notes in her book Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke, works like Gen and Fireflies “share in the collectivity of the Japanese memory as well as individual autobiographical accounts of personal suffering” (Napier 2001, 161). Hence, works similar to these films attempt to speak for history by employing a personal voice that has become well acquainted with “suffering, destruction, and renewal” (162). Many works that pull from the collective memory and trauma of the bombings are seen as part of a “victim’s history” narrative which works to promote sympathy from the viewer on behalf of the children they so often depict.

Contrary to more traditional works inspired by the suffering and social upheaval left behind in the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the apocalyptic narratives of works such as Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, Princess Mononoke, and Neon Genesis Evangelion. According to Napier, “apocalyptic imagery and themes tend to increase at times of social change and widespread uncertainty […] present-day Japan, shadowed by memories of the atomic bomb […] may seem an obvious candidate for having visions of the end” (194). While the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima have often been cited as starting points of apocalyptic imagery in Japan, many scholars have claimed that popular narratives within the apocalyptic mode should not be written off as mere references to this national trauma. Perhaps one of the most notable apocalyptic narratives in anime history is Kutsuhiro Otomo’s groundbreaking 1988 fantasy-drama Akira. The following article will focus on Akira and the significance of the telekinetic apocalypse it depicts in relation to post-war Japan, as well as the manner in which Otomo’s film resists interpretation. The film’s resistance to interpretation is particularly relevant in regard to claims that Akira should be unanimously interpreted as a reference to the bombings or even as anti-war propaganda.

Akira and the Atomic Bomb

It has been noted that the bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima are catalysts for present-day apocalyptic thought, particularly in Japan where the bombings actually took place. As the only country in the world to have suffered atomic destruction, it is unsurprising that the events of that August in 1945 still permeate the popular culture of Japan. Hence, in post-war apocalyptic works such as Akira the nature of said apocalypse is often rife with explosions and societal chaos; Japan is gripped by what scholar Freda Freiberg refers to as the “post nuclear sublime,” which is marked by the propulsion of the plots of animated works like Akira through the employment of Japan’s collective memory of nuclear disaster. Ironically, this results in an aura of both dread and desire within many apocalyptic films. In addition to the inherent spectacle of the apocalypse in Akira there is also implicit and explicit criticism of society, particularly in regards to the misuse of technology and the diminishment of more traditional social values.

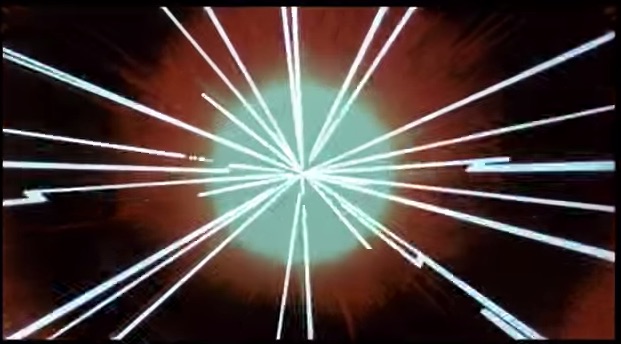

The opening sequence of Akira is subtle yet powerful. The camera angle travels down the streets of a city before the date– July 18, 1989– is superimposed across the screen. A bright white light suddenly fills the screen as an enormous explosion, illustrated by a semi-transparent black dome, engulfs the city and leaves only a black crater in its wake. This bright light, Freiberg has noted, is indicative of the tone of nuclear sublime that is present in Akira, as it “represent[s] the sublimity of nuclear destruction.” This area will be later referred to as “The Old City” or “Old Tokyo,” while the rest of the film takes place in Neo-Tokyo in the year 2019, 31 years following World War III. The crater that still mars the surface of Old Tokyo returns to the screen, filling it ominously before the audience’s attention is refocussed on the chaotic streets of Neo-Tokyo. This new city is rife with biker gangs, one of which the main character, Tetsuo, is a member of.

Like other works within the apocalyptic mode, Akira presents the viewer with the unsettling reality of abandonment and the death of the nuclear family. This is most clearly illustrated through the conditions of the two main protagonists, Tetsuo and Kaneda, who met and grew up in an orphanage together. Takahata’s Grave of the Fireflies also operates through this narrative of abandonment, as the main characters– Seita and Setsuko– lose their mother while their father is away serving in the Navy. While the pair are granted the opportunity to seek refuge with their aunt, the aunt is notably unsympathetic toward their situation, which leads them to run away to live in an abandoned bomb shelter. Like Seita and Setsuko, Kaneda and Tetsuo have likewise been abandoned by their parents, and have no close familial ties with anyone who is blood related to them; like the brother-sister pair in Fireflies, the main characters of Akira have only each other. With films like these, there is an obvious commentary occurring concerning authority, illustrated pointedly through the absence of the father. As Napier notes, the symbolic mode of “the death of the father” is extremely important for postwar Japanese culture: “Scholars argue that Japanese culture now exists in a demasculinized state, overwhelmed by feminine ‘cuteness’ but still haunted by images of a dead, absent, or inadequate father and problematic masculinity” (171).

The most obvious reason for the pervasiveness of this particular symbolic mode, especially in postwar Japan, is that many citizens actually did lose their fathers, either in the line of duty or during the bombings from allied forces. More than that, however, Napier notes that it was during this time that Japan lost “the cult of the emperor,” who was the father figure of Japan before the war, the “symbolic head of the Japanese nation-as-family.” In Fireflies, this absentee father seems aligned with a more “unproblematic vision of authority,” as the father is away working with the Navy during the war. In contrast, the father figure in Akira may be most accurately represented through Colonel Shikishima, who is the head of the secret government project concerned with researching the psychic children known as Espers. One of these Espers is known as Akira– the film’s namesake– and is the Esper which caused the enormous explosion that the film opens with.

Shikishima is depicted in the film as a tyrannical figure, one who is not only disillusioned by Neo-Tokyo– which he so lovingly refers to as “a garbage heap made up of hedonistic fools”– but is also determined to protect it out of an obligation that he feels because he is a soldier. These contradictory positions of Shikishima situate him perfectly as the father figure of this film as well as the authority figure. His position as father is perhaps best illustrated by his position as the primary caretaker of the Espers, most of whom are children, while his position of authority is maintained through his struggles to keep Neo-Tokyo’s corrupt government in line while also working to prevent another catastrophic psychic apocalypse like the one depicted at the start of the film. Situated opposite of Shikishima is Ryu, who is a part of a “terrorist” resistance movement in Neo-Tokyo. While he obviously acts as an authority figure in the sense that he is often seen giving orders or constructing plans for the resistance, he may also be seen as a father figure to Kei, a young female member of the resistance. However, he can easily be juxtaposed to Shikishima, as he does not possess the sense of obligatory protection toward Neo-Tokyo and its citizens as Shikishima does.

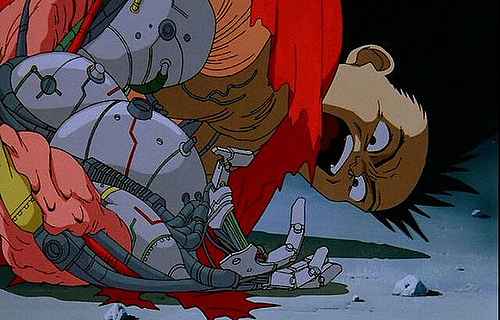

Unease surrounding cultural survival is another prominent theme of films within the apocalyptic mode, and Akira is no different. The figure of the feminine, which has often been cited for its great importance within traditional Japanese culture, is where this unease may be illustrated most prominently. Kaori, who acts as Tetsuo’s love interest, is depicted as shy and timid throughout the film. Despite her weakness, Kaori is also an embodiment of both security and comfort for Tetsuo. When he first escapes the government lab where he is being held, Kaori is the first person that he goes to see, urging her to run away from Neo-Tokyo with him. She agrees, but their attempt to escape ends with Kaori being brutally beaten and almost raped by members of Tetsuo and Kaneda’s rival biker gang. Like the female characters in other postwar films such as Fireflies and Barefoot Gen, Kaori is depicted as obviously weaker than her male counterparts. There is only one female character of note who can be considered a strong counterpart to the male characters: Kei. Kei, who is a member of the resistance, is always depicted as being on the front lines of conflict and often holding her own as opposed to the weak character of Kaori. Also counter to Kaori, Kei is not only able to escape the devastation brought on by Tetsuo’s psychic powers, but ends up developing minimal psychic powers of her own. Kaori, however, is engulfed by Tetsuo’s metamorphosing form and killed toward the end of the film.

Napier notes in her analysis of Fireflies and Gen that the death or uselessness of the feminine in these particular films may be seen as coding Japan as feminine itself (although scholar Patricia Masters states that “[Japan’s] national metaphors of self [become] essentially ‘trans-sexual,’ both ‘feminized’ and ‘viralized'”). According to Napier, in the case of Fireflies and Gen, Japan’s national identity becomes completely feminized through the images of weak or dying mothers and younger sisters. As Napier states, “this feminization leads only to despair and nostalgia for a dying culture. Grave of the Fireflies is thus an elegy for a lost past that can never be reconstituted” (173). Hence, while the figure of Kaori may align more with the lamenting of a forever lost past– a forever lost feminine– just as Fireflies and Gen produce through their female characters, the figure of Kei may act as a beacon of hope for both a resurgence as well as a reconstitution of not only the feminine, but also Japanese identity.

Insofar as Akira may be seen as a film concerning both the anxieties surrounding technology and nuclear war as well as a celebration of the potentials of reconstituting the self following chaos and social collapse, the theme of adolescence seems especially poignant. Certainly the themes of absentee fathers and problematic authority figures already situate the viewer in a space of unease and ambiguity, one which many could easily use to draw parallels to the struggles of adolescence. If the characters in this film are able to be situated as mirroring the condition of Japan in the postwar period, then it becomes even clearer that the progression of these characters throughout the film may also demonstrate a desire from Japan to move forward and reconstitute itself. Such a desire can easily be connected to the changes undergone during adolescence, which many can attest are rife with struggle, uncertainty, fear, and resentment. As Napier notes, “despair and a feeling of entrapment are emotions often associated with adolescence,” and in the case of Akira there is no better vessel for these emotions than the character of Tetsuo. Scholar Marie Morimoto has stated that “Dominant themes in Japanese cultural self-representation have long been those of uniqueness, isolation, and victimization – hence a lone nation struggling against all odds.” Building on this suggestion, Napier further notes that Akira’s release in 1988 was during Japan’s postwar peak, during which many were beginning to fear Japan’s emerging status as a global superpower: “Tetsuo’s monstrousness can thus be coded in ideological terms as a reflection of Japan’s own deep-seated ambivalence at this time, partly glorying in its new identity but also partly fearing it” (40).

Tetsuo begins in a place of weakness. Although he is a member of a biker gang, it quickly becomes obvious that his involvement with the gang is contingent on his close friendship with Kaneda, the gang’s leader. He is frequently depicted as being much weaker than his friends, especially Kaneda, whose bike Tetsuo is shown trying to ride but failing miserably, which results in ridicule from his friends. It is not until Tetsuo encounters an escaped Esper– a psychic child– in the street that his marginal status begins to reverse itself. While at the beginning of the film he is depicted as being almost entirely dependent on Kaneda and his other friends for assistance in the world of biker gangs and high speed motorcycle fights, the emergence of Tetsuo’s psychic abilities following his encounter with the Esper sets off a slew of changes within him that soon result in an immense power that no one – not even Tetsuo, to some degree – can control. Through the later half of the film Tetsuo undergoes a terrifying metamorphosis coupled with unrelenting psychic destruction, which “represents a form of all-out adolescent resistance to an increasingly meaningless world in which oppressive authority figures administer the rules simply to continue in power” (42). Contrastingly, the father and authority figure of Shikishima, discussed above, begins the story being in total control, slowly losing it as Tetsuo’s power grows, culminating in violent scenes of destruction.

As Susan Napier notes in her analysis of Akira, as a work within the apocalyptic mode it presents a vastly different approach to the issues that are tackled compared to other apocalyptic works such as Nausicaa or the environmental apocalypse narrative of Princess Mononoke. In many ways Akira positions itself as a film which celebrates the apocalypse. Napier notes that this celebratory mode of the apocalyptic narrative is shown through the film’s postmodern aspects: a rapid narrative pace which is reinforced by the soundtrack; an emphasis on fluctuating identity; the use of pastiche (in relation to Japanese history as well as notable styles of cinema); and the film’s historical ambivalence (Napier, 204). This historical ambivalence runs counter to other works within this apocalyptic mode, many of which have already been briefly mentioned here. Unlike other works, Akira’s storyline displays a negative attitude toward parents and the nuclear family more generally, illustrating the parents as having abandoned their children who instead opt for familial relationships with their peers. Additionally, Napier cites the final fight scene as a pivotal display of historical ambivalence: the fight takes place in Yoyogi Stadium, which was the site for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics “and a symbol of Japan’s resurgence from the devastation of World War II” (205). When the stadium is ultimately destroyed in the course of the fight, accompanied by yet another vignette of Old Tokyo’s black crater, Napier claims that “Akira literally deconstructs Japan’s past by blowing it away” (205). This deconstruction and questioning of reality culminates in the final scene of the film when Tetsuo is transported to what the audience can only assume to be another dimension. The film ends with Tetsuo’s disembodied voice declaring “I am Tetusuo,” which Napier claims illustrates Tetsuo’s transition from adolescence to adulthood, marking “his entry into the symbolic order” (44).

Unstable Ground: Akira’s Resistance to Interpretation

Akira has had a notable influence both within and outside of Japan. In many ways, the film may be credited for expanding interest in anime to cultures outside of Japan where, before Akira’s release, it held the most influence. In his article From Ground Zero to Degree Zero: Akira from Origin to Oblivion, author Christopher Bolton remarks that the opening sequence of Akira– the enormous explosion that decimates Old Tokyo– can be seen as a metaphor for anime’s future success in the United States and elsewhere. Citing a “popular guide to anime,” Bolton writes: “just as the bubble of Japan’s economy of the 1980s was about to burst, a bomb of a more positive nature detonated, with the premier of Akira” (Bolton, 296). Bolton builds on this metaphor, noting that this very explosion has clear parallels to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which the United States was ultimately responsible for. To be an American in the 1990s watching Akira was to be “at the very same instant […] lifted out of the story and out of the theater to see a flash of a new future for Japanese film.” It is this dichotomy of both fear and desire which perfectly encapsulates Freiberg’s notion of the nuclear sublime that has been claimed to be present within Akira. The film, as has been stated earlier, clearly celebrates the apocalypse while also transporting the audience back to a time of fear and anxiety; a time of pain and of trauma. Bolton goes on to call the film “a celebratory, artistic, and even metatextual [work] that seems to productively explode the rules or boundaries […] [it is also a] dark immersive or illusionistic historical reminder.”

While the ability to read Akira as an attempt to reckon with the trauma of the Nagasaki and Hiroshima bombings is compelling, and in some cases productive, various theorists have remarked that Otomo’s film may be up to something different. Christopher Bolton himself claims that “[such a reading] suggests Hiroshima and Nagasaki as original traumas that are then worked out and mastered through their repetition in popular culture” (297). As Bolton explains, it is society’s strong need for a point of origin which allows for the theory that films like Akira are dealing with traumatic past experiences to hold water. What people want is a “big bang from which all else springs,” something to satisfy this strong desire for an origin or an explanation. For Bolton, this search for an origin should be avoided, or at least should be highly scrutinized; the idea that a decisive origin has been found, Bolton claims, results in a closing off of more complex or even more productive interpretations of such films (298). This desire for origins has a long history, one which is closely tied to philosophical theories of presence and transcendence, particularly within metaphysics. The so-called discovery of origins has the ability to anchor interpretations and to close off alternative meanings, and while the idea that Akira is borne from the trauma of atomic bombings is certainly compelling, many theorists “remain [convinced] in their core contention that Akira is a text about the unreliable function of language itself.” Hence, while Akira may indeed be argued to contain anti-war imagery, and it is easy enough to draw parallels between the story, the art, and the atomic bombs, it is important to keep in mind that in many ways Akira purposefully works to undermine “unitary meaning.” Bolton’s analysis of Akira shows how the various political movements that undergird the film’s plot– a coup led by Colonel Shikishima, the Resistance movement, and the cult which worships Akira– all harken back to various political movements of Japan’s past. It is this amalgamation of various political movements within the film that causes theorist Isolde Standish to call the film’s politics “pastiche.” This pastiche of historical contexts, according to Standish, works to rob the elements within Akira of any historical context. Hence, Akira’s use of pastiche disturbs the stable ground on which an origin or transcendent meaning rests “and portrays a world in which there is no stable ground that could anchor interpretation” (299).

Akira has often been referred to as a postmodern work, and the film’s ability to fall within this artistic form is also what allows for it to escape interpretation. Postmodern theories, particularly in regards to art, analyze “the pace and flood of language” within particular works of art and literature whose political narratives are difficult or even impossible to construct. With Akira’s fast-paced narrative, which is flooded with “a ceaseless rotation of visual images,” the plot of the film becomes noticeably incoherent, which is a prominent focus for theorists who analyze the film through a postmodern lens. This swift movement between imagery and language is identified as a common trope of postmodernism, and theorist Fredric Jameson claims that it is this particular choice in artistic expression which illustrates “the breakdown of the signifying chain… an experience of pure material signifiers, or, in other words, a series of pure and unrelated presents in time.” It is this breakdown of the “signifying chain” which allows Akira to occupy a space that is both a historical narrative as well a breakdown of a sense of time and self, which in effect can erase the audience’s sense of any historical narrative at all. It is Akira’s postmodern artistic construction which allows it to resist solid interpretation. Both the reading of Akira as being inspired by the atomic bombings as well as the theories that lean toward postmodern interpretations are compelling and, according to Bolton, have the ability to be combined. Hence, while Akira itself may actively resist interpretation, especially in regard to origins, one may still be able to consider Akira and films similar to it as being directly related to the trauma of the atomic bombings in 1945. As Bolton himself claims, “the atomic bombing represents the end of conventional history and representation, and the inauguration of a Japanese postmodern” (301).

As a film within the apocalyptic mode, Akira clearly stands out as a tour de force of apocalyptic destruction, societal breakdown, and carnivalesque surrealism. The influence of the war and the Atomic bomb more specifically are clearly present within the film’s storyline as well as its artistic execution, though this seemingly simple interpretation should be carefully scrutinized. Although it was released in 1988, Akira has continued to be influential both on future cinematic works– animated and live-action alike– but has persisted as an icon of resistance, as well. The far-reaching influence of Akira can be most clearly illustrated through an anecdote related in Napier’s work concerning Japanese critic Toshiya Ueno’s visit to Sarajevo. As Ueno wandered through a war-torn Serbia he encountered a crumbling wall of a building which had a striking display of graffiti. The piece in question, a large panel of artwork decorating the side of the bombed out building, consisted of a scene from Akira in which Kaneda declares: “So it’s begun!” Rarely has an animated film had as much influence on so many cultures as well as had such relevance for its audience. Akira continues to stand alone in its ability to collapse the past, the present, and the future together in such a way that undermines desires to attach a definitive meaning to the work itself.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

That was BEAUTIFUL! No other words to describe it. Going to pass this on as a perfect explanation what akira is about. Thanks a lot for the effort of writing this article.

thank you very much for your comment, I’m very glad that you enjoyed this piece since I had such a wonderful time researching and writing it. thanks for reading!

The Japanese have a different idea of what near world ending cataclysms/apocalypses look like. I have to imagine this is due to their history of not only having survived the destruction of most of their major cities only to recover fairly quickly, but their long history of being a nation ravaged by earthquakes and tsunamis, which would give you a sense that your civilization or your city is impermanent, but will be rebuilt.

It’s nice to read about Japanese anime without the usual negative focus on the violent and sexual side (which does exist).

Akira would kinda be a poster child for (well done) anime ultraviolence though…

Personally I’m kinda disenchanted with most anime these days. I find more interesting the more unusual works. Couple of examples.

1. Planetes – garbage collectors in space. Hugely ambitious philosophically and politically, but never forgets to make it fundamentally about characters.

2. Everything by Mamoru Hosada. The next Miyazaki for sure. Like Ghibli’s works, but more narratively coherent, more innovative in conception, less inclined to be pigeonholed into a single formula. Every film he’s made has won highest accolades in Japan. Really should be better known.

Great article. I recently got the soundtrack which is by Geinoh Yamashirogumi, absolutely brilliant!

Always loved the soundtrack, I think it’s under-appreciated as to how original and unusual a soundtrack it is.

Akira is just totally amazing, I’ve been crazy about that film for about 20 years, I remember when I first saw it on TV very late at night and I couldn’t keep up with the subtitles, I thought Kaneda was Akira and totally didn’t understand it! Still to this day I’m not 100% with what happens at the end but I don’t care it’s so bloody good!

I collected the Akira comic books when I was between 17 and 21, but kinda lost interest after that…. good art, but the story meanders on and on for thousands of pages. am I the only one who tends to think of it in ‘young adult’ terms, much like listening to noisy ‘lets go out and get drunk’ indie anthems? It’s a rock n roll kind of thing, young people in the future driving motobikes and taking drugs.

I think if you can get the whole collection of the Akira manga and read it in a shorter space of time, it doesn’t seem so meandering. I bought the 6-part paperback edition from Dark Horse and absolutely loved it. A much clearer, more focused story than the film.

I tend to compare it with something like Moebius & Jodorowsky’s “The Incal”, which I read much earlier, aged 12 or 13. Otomo is alright, but Moebius is a visionary illustrator on an entire different level. And the “The Incal” storyline covers a much broader palette in the space of a nice compact 300 pages. I guess I tend to be impatient or something.

An excellent piece of work and thank you for a fascinating read.

It’s a stunningly beautiful (and purposefully ugly) film, and you did justice to it with this analysis.

80s japanese animes are still the best. Novadays animes seems too…artificial and clumpsy.

I enjoy Akira, but I think it’s a little overrated. It’s good, but not as good as everyone likes to make it out to be. Definitely has a large historical significance in the world of animation, for japan and America as well. I just don’t think it’s the greatest animated movie of all time like many others do.

I just got finished watching Akira. I read this article before which made me want to watch the movie. I really enjoyed it. I’ve been meaning to watch it for years but just never got around to it. This article didn’t ruin the film for me, it just made me appreciate it more while I was watching.

the good days back when anime was well written and interesting and had an artistic flair to both the storyline and the animation itself, and both the writers and animators put forth real effort and sacrifice to bring it to life. as compared to modern anime, thats pretty much just a bunch of weird quasi political satire and CGI catgirl panty shots. i can only be glad we had nineties anime to bring people like me into to the fold before it got to weird to appeal. i miss cowboy bebop.

I watched this with my kids and the dream sequence was and possibly still is the scariest scene in any film I have seen. I remember HMV (in England) had shelves dedicated to Anime’ in the early 90s; but gradually people realised that most of it was absolute shit in comparison to Akira.

I think it’s more of a case of HMV stocking anime that wasn’t all that great. Plenty of anime series’ are as good if not better than Akira.

Bebop as a whole is better than Akira in my eyes (Although that comparison can’t really be made, Akira being an OVA and Bebop being a series)

It introduced Western audiences to the possibility for serious animated genre film, and is worthy of note for that (even if later films like Ghost in the Shell are better in terms of plot).

I personally was never a massive fan of the film – I can see its value and influence though – but I love the comic.

Adult male over 50. Thought Anime/Manga was silly. Then I stumbled upon a thing called Death Note that my boys were watching.

For the umpteenth time in my life I was proven wrong. Gripping, fascinating and even humbling. I am not suddenly a rabid fan but it opened my eyes. Also introduced me to the surprising world of Korean/Japanese music. Sure some of it is bubble-gum, and so it is in the West, but some of it is extraordinary.

I literally worshipped Death Note when I first read it, that’s until I read ‘Liar Game’ which IMO if you think DN puts you on the edge of the seat, LG will def topple you over.

I watched Akira when I was 12 and found it soooooo confusing. My friends and I ended up watching it so many times just to understand it.

We ended up watching stuff like Fist of the North Star and just going for the gory stuff.

Was it just me who found it difficult????

I think that I touch on this a bit in the article, but many scholars conclude that the film is intentionally confusing. As I wrote in the article, Akira utilizes pastiche to create an unstable and uncertain plot line that is intentionally difficult to follow or interpret. I think that it is for this reason that many viewers feel that they do not understand the film, but after a lot of research on theorists who look at Akira and other similar works through a postmodern lens, I believe that the whole point is for no one to understand it entirely. Thanks for reading!

I love plenty of films that are hard to understand, but I only really appreciate Akira after reading the manga and getting a better idea of what’s going on. I think the time limitations of the format – plus the unfamiliar cultural style (Akira is often the first anime people watch) make it a bit difficult for many viewers.

I think that there is a lot to be said for how reading the manga as well as watching the film can influence one’s understanding or interpretation of either medium. It’s very possible that reading the Akira manga could perhaps clear up a few things that are confusing about the anime, but ultimately I believe that each medium accomplishes very different things and in very different ways, stylistically speaking. Even the endings of each work are drastically different, and thus leave the viewer/reader with a very different message. Bolton delves further into the similarities and differences between the two in his own article, and I think there is so much more to be said/investigated in regard to the relationship between the manga and the anime!

No, it is a pretty muddled film, an adaptation that rather relies on being familiar with the source to properly “get” what’s going on.

Perhaps it could be argued that those more familiar with the manga can better grasp what’s going on in the film. However, I don’t think you should be too quick to dismiss the point of many theorists that the goal of Akira as a film goes beyond the plot of the original (I use this word tentatively) work of the manga. I would implore you to not be so quick to dismiss it as “muddled,” or only working to cater to people who are familiar with Akira’s broader context. Further into Bolton’s analysis of the film that I reference he brings in the manga and investigates it alongside the film, saying that “although the film was in some sense adapted from the manga, it is not my intent to treat the manga as a backstory or a better story that will answer all our questions about the anime. That would simply replace one origin with another, replacing genbaku (the nuclear bomb) with gensaku (the nucleus of the franchise, the original text).” I think such an approach is very interesting, and that upon further investigation this perspective undermines critiques like the one you give here that the film is completely based on the manga and that those more familiar with the broader body of work behind Akira have some sort of deeper insight.

Really, really good analysis. But being honest I’m not too sold on Akira. Top marks for animation and soundtrack. But the characters were fairly one dimensional and the plot simplistic. Just because it deals with politics doesn’t mean it’s ‘adult’ especially as it does so in the most puerile throwing the toys out of the pram level.

Ironically I think the real high mark of 80s anime was the children’s TV series Mysterious Cities of Gold which if anything had more complex characters and plotting, even though it worked well for children too.

Akira is an experience every time you watch it. It never gets old. Millions of details to salivate over.

I wonder what’ll be the next akira or the next big bang that’ll change manga and anime as a whole?

Wonderful insight and apt critique! I agree on all levels. What a beautiful piece of art it is.

You gave Akira tribute that it deserves. I remember when I was about 10 or 11, my older cousin who was visiting from overseas brought with him Akira on VHS. This was my first experience with anime and I was blown away. I never thought before that time, that a cartoon could be so violent and dark. I fell in love.

Always loved the original golden age of anime, always disliked fanservice hungry otakus though, really cant believe how the medium got destroyed, Akira, Wings of Honnêamise, some of my favorite all time pieces of art from the 80’s. In fact i often found many anime movies far more immersive compared to live action movies from the time, when you draw you can create anything. I am so thankful we were on the right time on earth to witness people Katsuhiro Otomo glorious work.

Im thirty now..who knows what kind of thirty year old id be if my 15 yr old version hadn’t sat down and watched this mesmerising, beautiful piece of work.

Drawn animation never looked so good, though the Japanese story-telling conventions sometimes took a little while to get used to.

The Japanese Anime created much more interesting and diverse an creative energy stories using art. Even as a kid these were fascinating as well as amazing attention to detail for animation as you’d find echoing the complexity in the natural world and in reality. Disney seems by comparison either 1) Teddy Bear’s piccnic or 2) Fairy Tale the young knight finding his princess. Which are not bad children’s stories but generally conservative.

Saw this in the cinema, it blew my mind. It’s possibly also why I cannot take the bulk of modern anime/manga seriously.

Yeah I know it’s a horrible sweeping generalisation, but after Akira and Ghost In The Shell I do not need much else.

I see what you are saying but you just need to find the right stuff – the majority of any medium tends to be dire.

If you are into comics at all then try Naoki Urasawa’s stuff.

I never liked Akira, and I watched it when it came out, I even read the manga to completion and didnt like that either, just felt obligated because it was so popular. I think Id have actually enjoyed it if the Colonel was the main character.

A really interesting analysis and it touches on a number of interesting socio-cultural insights to trends that continue. It is interesting that were the nuclear bomb has been a mainstay of Japanese pop-culture it has been less represented in American, one cannot help but wonder if there still remains a level of national guilt that ensures this topic arises less?

I would say that you’re definitely on to something there, and I think Freiberg’s theory of the post-nuclear sublime may play into that as well. As Bolton notes in his essay Akira’s premier in the United States had such an impact due to the innate qualities of dread and desire that the post-nuclear sublime incites. Being citizens of the nation that was responsible for so much destruction very likely plays a major role in this.

I’ve loved Akira since I first saw it as a kid and gotta say, I couldn’t have summed up my feelings about it any more perfectly than you have here.

Nice content, I do really love Japanese film especially when the storyline evolves in technology and government, and kinda secret things that are meant to be told.

Akira is an astounding piece of work, every frame of it still as glorious today as it was when it was first released.

Akira is one of the animes that just spooked me out but interested to watch over and over again. Thanks for the read.

Akira is phenomenal. Will still be one of the best anime movies ever made.

I am really glad that this article got published! Akira is definitely one of the best anime movies, along with Hadashi No Gen, that portrayed the trauma of the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A good essay. Imagine that the two Atomic bombs dropped in 1945 still resonate with Japan today. Prior to the dropping of those two bombs, there was the firing bombing of Tokyo–which may have killed more than those killed by the Atomic bombs combined. I wonder if the firing bombing of Tokyo carries any lingering effect.

First of all Grave of the Fireflies doesn’t depict the atomic bombs and is set closer to Tokyo, the children die from homelessness (starvation) after a bomb run destroys their town and they run away from family care. I think as a scientific writer and an anime fan, philosophy can be a pit of obsession. For me anime has drifted from history or popular media to art and humor, losing a lot of its value along the way. Just a penny for your thoughts.

thank you for your comment! however, i don’t believe that i ever say that Grave of the Fireflies depicts the atomic bombs, nor do i claim that the children die in the bombings. what i hoped to illustrate by bringing in works like Fireflies and Barefoot Gen was that works like these share in a collective narrative and exploration of national trauma—at least, this is what many theorists claim. thanks for reading!

thanks for this! very interesting read. i’ve always thought about how japan is in a super unique position as both a big aggressor in world war 2 and one of the wars biggest victims. even tho their govt doesn’t let them as a country come to terms with the former, we still get a lot of great works about that time (not to say everything written about that time is great, a lot isn’t, but there’s a lot that is).

Grave of Fireflies was about firebombing by the US, not the atomic bomb. I fail to see how Mononoke is post apocalyptic. It was set in fuedal times and deals with man vs nature and man’s abuse and destruction of it. Nothing post apocalyptic about it.

For the first-time viewer Akira the movie might be a little confusing, but having read the manga and then watched the movie, I enjoyed each and every bit of a movie that still sticks with me to this day. As an aspiring writer and animator, with a lot of interest in anime, Akira was an eye-opener and the influence it has had in the growth of the field is paramount. What I love about Akira is that it is open to so many interpretations both within the cultural and societal history of Japan, as well as a stand-alone science fiction work.

Additionally, the anime In this Corner of the World also provides a depiction of the collective narrative and national trauma following World War 2 in Japan. Unlike the Grave of the fireflies, this one focuses more on the atomic bombings in particular.

Thank you so much for writing this article! It was actually immensely helpful for my final essay for my English class, as it pointed me in the direction of some good scholarly articles which analyze Akira. There’s a novel called The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao in which the protagonist is later obsessed with the film, and reading your analysis helped me understand the symbolic significance the it might hold for that character. If you haven’t already read the book I’d highly recommend it!

Thanks for this essay. I really enjoyed it and appreciate your and Bolton’s warning not to concede too quickly that Akira is all about those two days in 1945. I think looking at themes around the lack of parental/father figures in a post-war, adolescent Japan is more likely to bear fruit.

I was surprised after my most recent viewing how many times characters hurled age as an insult at each other, as well as the number of times that a character’s sympathy and concern for Testuo triggers anger in him.

On the contrary, early in the film when the Colonel takes the little girl’s hand to comfort her after her apocalyptic visions, it is a surprising reveal of his true nature, and a powerfully tender moment.

Thank you! It was really interesting and exciting too read.

Wow. That was epic. My eyes kinda hurt from reading but that’s chill, it was a powerful analysis. Beauty can come from disaster and ‘Akira’ does this superbly. Using the nuclear attacks on herself as inspiration, Japan was able to unleash a flurry of beautiful works of art. It’s nuts how creative they can be after dealing with so much strife and devastation. This was wonderful, well bloody done 😛

Hello,

I will share the link to your excellent article about Akira with my Film Studies course.

Would you be willing to email me your full name so I can credit you properly and so my students can cite your article properly when they quote your article in their writing?

Thanks for considering,

Luke Walden

email is my last [email protected]

Luke, I will connect with you shortly about this.

Super analysis

It was very validating to read the postmodern ideas and thoughts of and about the film. I consider the visuals themselves as representing postmodernist thought. The constant exploding out of things from the bombs, to the giant toys, to canisters, to the containment unit, to Tetsuo himself.The presentation of each of these things that explode is initially “normal” looking even mundane, yet they erupt often to disturbing effect upsetting the “normal” and in most cases consuming it.