Returning Gravitas to American Girl

In 1986, former teacher and entrepreneur Pleasant Rowland launched the eponymous Pleasant Company from her home state of Wisconsin. Rowland used her new company to create the American Girls Collection, the first three dolls of which debuted in 1993. American Girls, Rowland stated, were meant as an alternative to baby dolls and Barbies, the most common dolls girls of the era had available for their playtimes. While these dolls filled certain niches, Rowland noted their focuses could send narrow messages. Baby dolls placed girls in perpetual caretaker or “mommy” roles, while Barbies looked more like teenagers than the prepubescent girls playing with them, and were often associated with the material excess of the 1980s.

With American Girls, Pleasant Rowland intended to create a line of dolls that not only “looked like the girls who played with them”–authentically “little” girls with less stylized features than Barbies or babies–but would educate those girls as they played. Each American Girl would have a six-book historical fiction series centered on her era. The books would see their heroines experience such realities as war, poverty, racism, industrialization, and child labor or abuse. However, the presence of intrepid, resilient heroines and age-appropriate treatment of situations and stakes, would keep history both accessible and exciting.

Girls who read the books and played with the dolls would find new, relatable fictional friends. Moreover, they would find voices across history telling them that even though the events of the wider world were “big,” the “smaller,” girl-sized problems and emotions they faced were timeless. Her initial successes wilted into mixed reviews and outright failures, but plenty of opportunity exists to reunite the spirit of the “old” American Girl with the “new” successes that currently exist.

When we speak of “gravitas,” we refer to “dignity, seriousness, or solemnity of manner.” This does not mean American Girl ever had to be completely serious or scholarly to be taken seriously, nor does it now. It does mean, however, that certain incarnations of the brand have struck a deeper chord with child and adult readers than others. It does mean, some characterizations and plot arcs are deeper and more dignified than others. When we speak of American Girl maintaining or losing gravitas, we speak not of a wholesale loss of dignity, but a slow slide away from the “seriousness” and maturity its young readers were once able to explore through the brand.

Therefore, when we speak of “returning gravitas to American Girl,” we speak of a desire to return to seriousness and the challenges of age-appropriate, yet mature stories. Several ways to return gravitas exist. Finding them requires examining the historical and contemporary American Girl lines as they exist, teasing out existing dignity and maturity, and finding where the brands have gone wrong. Once we have this information, we can determine how to bring back dignity without retreating to the past, and whether “wrongs” can be redeemed.

The Original Fabulous Five (or Seven)

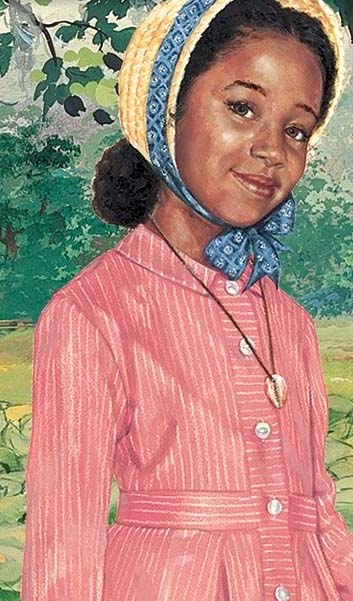

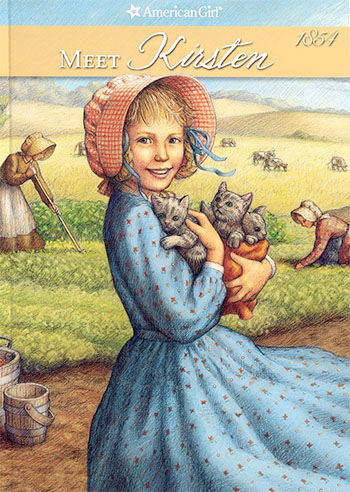

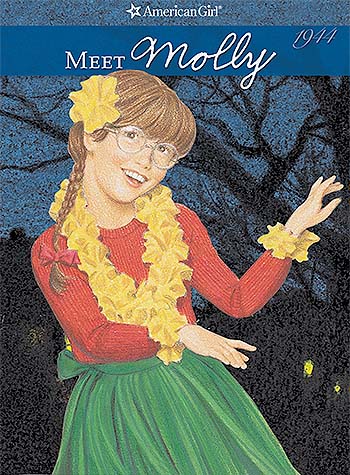

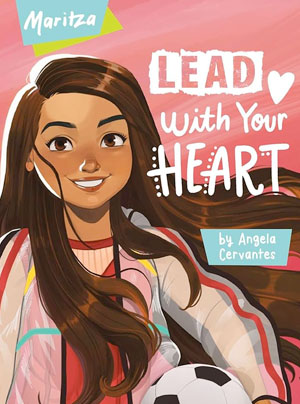

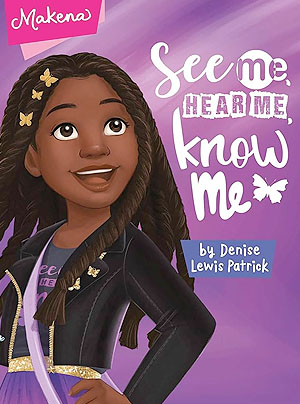

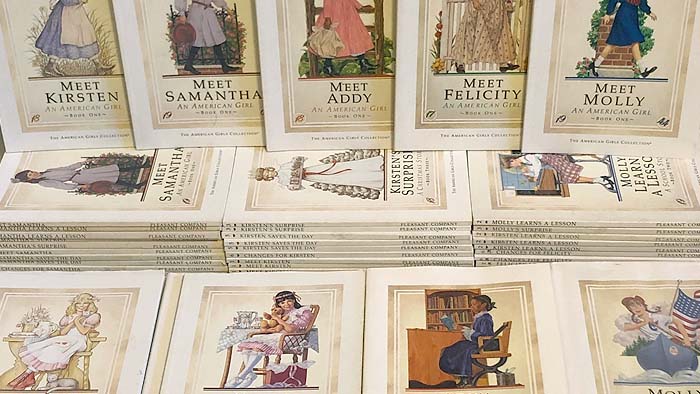

Within a decade, Pleasant Rowland’s original American Girl line–Kirsten Larson, a Swedish immigrant from 1854, Samantha, a privileged New Yorker from 1904, and Molly, a Midwestern middle class girl growing up on World War II’s home front–had grown to include Felicity in 1991 and Addy in 1993. The former was a budding Patriot from 1774 Colonial Williamsburg, while the latter, the line’s first Black doll, began her story as a North Carolina slave in 1864, escaping to freedom in Philadelphia at the end of her first book. This quintet, sometimes known as “the original five,” formed the backbone of American Girls Collection’s best-known, arguably golden, era among the millennial women at which they were aimed. The original quintet is sometimes expanded to include Josefina Montoya and Kit Kittredge, released in 1997 and 2000 respectively, but “the original five” are usually treated as part of their own generation.

The girls of the original quintet are extremely different in several ways. They hail from different states, with Kirsten the furthest north in Minnesota and Addy originally the furthest south in North Carolina, before relocating to Pennsylvania, where she escaped slavery in 1864. Most of the girls have a nuclear family base, but in everyday life, that family may not act like the traditional “Mom, Dad, boy, girl, and baby” combination. Molly has two living parents, but with Dad serving in World War II as a medic, Mom acts very much as a single parent. Addy is also from a two-parent family and a middle child with an older brother and baby sister. But her dad and older brother are sold in her first book. If Addy and Momma wish to escape slavery safely, they must leave toddler Esther behind. Thus, Addy spends over half her series as a de facto only child of a single mom.

The girls also exhibit vastly different personalities. For instance, Addy, Kirsten, and Josefina are all introverted and show academic bents. But while Addy eventually becomes a top scholar in the running for a scholarship to an all-Black youth college program, Kirsten struggles with the new language and expectations of her school, showing the most aptitude for subjects she finds interesting. For her part, Josefina, like Addy, has to become literate at age nine. Once she does, she becomes dedicated to study, but not necessarily bookish. Rather, Josefina throws herself into healing. In so doing, she shows an appreciation for the practical–her community doesn’t have access to professional doctors–and an 1824 version of aptitude for STEM.

American girls growing up with the original five could find something to relate to in any and all of the original 5-7 characters. Readers and players quickly found treasures in both the dolls and the books chronicling their adventures. In fact, this writer remembers the books, not necessarily the dolls, earning prominent spots on her Christmas and birthday request lists. No matter how many dolls they had though, if any, the American Girls (AG) demographic loved their fictional friends’ adventures. Such adventures pulled readers in because while the “backdrop” of a major historical event or period always loomed large, problems a girl between the ages of 9 and 12 found more manageable remained in the foreground. Still, the two “halves” of each story never eclipsed each other.

Girl-Sized Plots With Grown-Up Backdrops

The original 5-7 American Girls were introduced to girls who, thus far, had not encountered a “book and doll” format in historical fiction. Real-life girls who read this genre likely enjoyed the protagonists and may have identified with them based on age, sex, race, or some external factor. However, real-life girls also probably got the idea historical fiction was “serious,” not a genre or cadre of topics with which to “play.” This would have created a detachment and separation between the average girl reading historical fiction, and not only the genre, but history itself.

When Pleasant Company and American Girl sought to fill this gap, they knew they must do so with protagonists to whom girls could relate internally, not just externally. Having the same red hair as Felicity or wearing glasses like Molly would not be enough. Nor would similar, but small struggles such as poor performance in a school subject or concerns about what the winter holidays would look like in a lean or stressful period. American Girl’s readers would need an exact mix of historical seriousness, plus “girl-sized,” relatable problems that not only affected their favorite protagonists, but served as microcosms for the surrounding narratives. Thus, American Girl’s first “generation” of heroines was born with the challenge of getting this mix correct, not once but 5-7 times over 30-42 books per heroine.

As Kate of the YouTube channel Babbity Kate says, the original historical line didn’t get everything right in this mix. In her videos, she points out that some of the “family values” seen in the books can jar 21st-century readers, and some practices are just plain outdated (ex.: the use of corporal punishment in schools and at home, the lack of sympathetic responses to trauma). But Kate goes on to say, the original line created “nuanced [girls inside] complex worlds,” which gave real girls great “windows” and “curiosity” about what their lives were like.

Historical Eras, Timeless Emotions

The “foreground” of an AG heroine’s story always related to the background somehow, sometimes overtly but often with more subtlety. The books’ titles hinted at the relationships. For instance, the first book was always titled Meet ____, with the heroine’s name filled in. The introductory novelette would focus on setting up the character’s historical period, the trials she faced, the major goals she would work toward, and the arc that would follow her through the next five installments. Kirsten Larson, for example, immigrated from Sweden to Minnesota in her “Meet book.” Introverted and given to timidity, Kirsten struggles with adjusting to her new country without letting the harshness of immigration and frontier life squelch her courage.

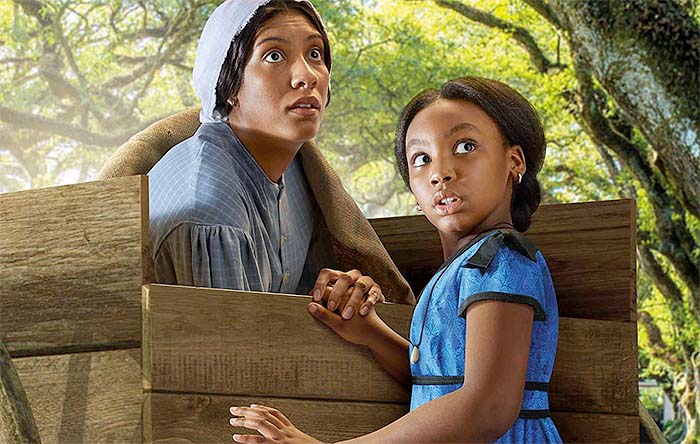

In her “Meet book,” Addy Walker does escape slavery, but not without living in its realities for nine years. When readers meet her then, she not only faces a life-threatening journey, but grapples with trauma’s aftermath, the need to “stuff” her emotions down for survival, and bitterness toward all white people. Unfortunately, slavery and pre-Civil Rights mores mean Addy must “mask” her emotions more than a girl her age should ever need to. She must be braver than a girl her age should need to, and make mental and emotional decisions beyond her years. Still, Addy makes the decision to do what her mom says and let love fill her heart instead of hate. When she does, she gives modern girls, especially those of color, a solid solution for the microaggressions and outright hatred they still face.

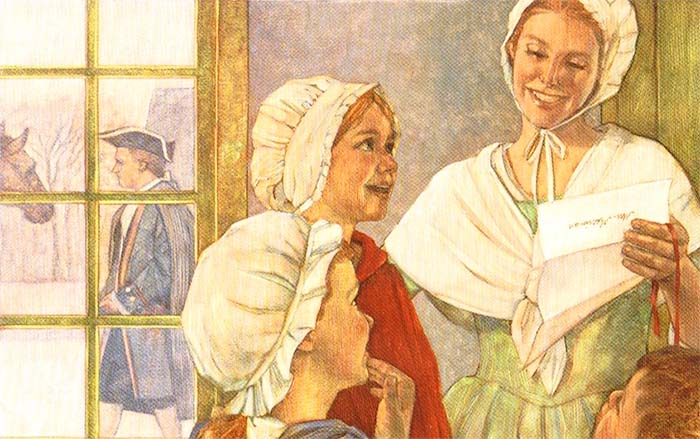

Even in AG books that do not cover “big” or “serious” topics, this same combination and gravitas can be found. The third and fourth books in each of the original quintet to septet’s collection concern holiday celebrations (usually Christmas) and the heroine’s tenth birthday, respectively. These are not usually occasions to discuss war, abuse, or the like. Yet these issues remain in the background and make the associated stories stronger. For instance, Felicity’s Christmastide involves an invitation to the governor’s New Year’s ball. The party will give tomboyish, independent Felicity a chance to show the social graces she’s learned at Miss Manderley’s school for gentlewomen and prove to her parents their investment was well spent. But the invitation also means leaving the sickbed of her seriously ill mother, who has tried to hide her illness throughout December but worsened over the season.

Felicity’s dilemma is juxtaposed with choices between the obvious persecution Patriots face, vs. the privilege, but tension, Loyalists like her teacher Miss Manderley and best friend Elizabeth currently live with. Felicity ultimately gets to “take a third option,” but her choice never reads as an easy way out or having it both ways. Instead, Felicity understands both paths have a price and the test of maturity comes in choosing the one you are willing to live with. When she chooses to stay with Mother on the night of the ball, she acknowledges that choice comes with the intrinsic reward of deciding for herself what the “right thing” is. This will stay true even though she’ll miss the ball and the chance to prove herself a “young gentlewoman.” But when Father and Mother respond to Felicity’s compassion with a way for her to attend the festivities after all, it doesn’t read as Felicity’s fairytale reward. Rather, it reads as the book’s expected “surprise.” It also sends the message that hard choices and unexpected boons go together in every era.

Girl-Sized Microcosms for National Changes

In another book, when Molly McEntire and her new friend Emily Bennett have a blow-up over how Molly wants to celebrate her birthday, it might read as if the girls are fighting about food and clothes. But when Emily, a British evacuee, bursts out, “Food and clothes! That’s all [you Americans] care about,” Molly and readers get a needed reality check. Molly knows some of the pain of World War II. Her physician dad is overseas, and she misses him terribly. Mom has had to start working, leaving Molly and her siblings in the care of a well-meaning but often strict housekeeper. Rationing has meant giving up many luxuries she loves, and even her leisure time revolves around the war effort. But as she admits to Emily, “[The war] hasn’t been as real for me.”

Remembering her friend has lived through the bombings, death, and trauma she has only heard of through newsreels and gold stars in windows helps Molly adjust her perspective. Molly realizes for the first time, WWII is real, and while it may not destroy her house or kill her loved ones, it could kill relationships she holds just as dear. She and readers have a chance to gain empathy and interact more intelligently with events that may be far away, but affect real people every day. Indeed, Molly takes her opportunity, letting Emily lead the plan for their joint “English tea birthday” and naming the puppy she receives as a gift Bennett, after her brave new friend (while Emily names hers Yank, showing new respect for Molly and Americans).

The gravitas of this combination never wavers through five heroines and 30 books. For fans who add Josefina and Kit to the original lineup, said gravitas gets to spread to the pre-U.S. annexation of New Mexico in 1824 and the Great Depression in 1934. Pleasant Rowland and the authors of the original AG books accomplished their goal in that history became relatable, accessible, and exciting to modern girls ages 9-12. More importantly though, the original series’ gravitas ensured something deeper happened below the surface. Although they were likely unaware, the American Girls Collection’s first readers and players absorbed a valuable message. Between five and seven voices spoke to them across history, saying, “We faced our challenges for our eras. You may hear that yours are too big or for adults only, and you may not face what we did. But if and when you face something similar, you can succeed and grow like we did.”

This message landed because it united macrocosms with microcosms, real hardships with the safety of everyday life, and world-altering events with questions related to burgeoning maturity, such as how to handle friendships and familial expectations. American Girl carried one of the ’90s biggest messages of female empowerment.

A New Octet for a New Generation

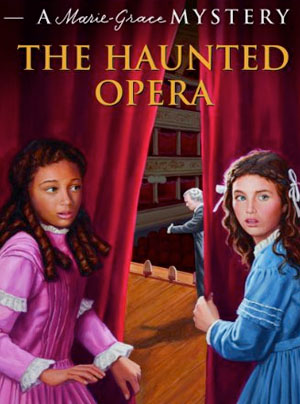

While Josefina and Kit are often added to the original quintet, their respective releases in 1997 and 2000 can be seen as the end of an era. In 1998, Mattel bought out Pleasant Company. The buyout heralded some potentially great changes for American Girl, which many new fans and their adult parents and guardians enjoyed. One such change, years in the making and arguably overdue, was the addition of even more historical characters. During the aughts and New Tens, the “second generation” of American Girls that began with Josefina and/or Kit, gained six more heroines. Altogether, the new septet included Kaya, Cecile, Marie-Grace, Rebecca, Julie, Caroline, Maryellen, and Melody.

The new octet was birthed for the generation who would grow up in the new millennium, a new historical era with new developments and expectations. The new octet’s stories, and the history behind their dolls, still held onto some of the original quintet or septet’s format. However, certain elements changed in large or small forms. The changes ushered in an eclectic mix of successes and failures, and which were which depended entirely on who was being asked.

Historical Success: Diverse Heroines, Multifaceted Stories

More Self-Determined Girls of Color

Discussions of diversity, inclusion, and equality are often seen as a product of the 2020s or mid- to late New Tens (circa 2015-2019). The truth is, these concepts gained steam as early as the aughts. The AG brand was on the cutting edge. Granted, some of their position came from negative backlash over the original quintet/septet and what these heroines lacked. For example, after the release of Kit Kittredge, the racial balance of characters was still 5 white to 2 girls of color (70% vs. 30%).

Parents and guardians had taken to the Internet and new social media to raise these concerns, as well as related ones. When white girls and their moms complained Addy’s textured hair was too hard to style, AG fans of color rebutted that the author of the Addy books, Connie Porter, had been approached with the issue of textured vs. straight hair while Addy’s line was still in production. Porter is Black and had been told that Black girls of Addy’s time period could and did have straight hair. But Porter pointed out giving a Black doll from 1864 straight hair would mean, “explaining exactly why that was.” In other words, Addy would have had to be a mixed race child, or a child who read Black, but still had genes coded for White skin. This would mean she would likely be written as the product of an affair or rape. Neither topic was or is considered age-appropriate for AG’s target demographic.

AG sought to expand their diversity, not just through race and color, but other traits and backstories. Kaya’naton’my, or Kaya, burst onto the scene in 2002 to great fanfare as AG’s debut First Nations heroine and doll. Her author, Janet Shaw, is white, but had a whole team behind her, ensuring meticulous research into Kaya’s tribe, the Nez Perce. Kaya’s books also make clear that though her grandparents have experienced European-initiated tragedies like smallpox, Kaya’s 1764 story takes place before “major” European contact. Additionally, instead of being confined to a state, Kaya lives “somewhere in the Pacific Northwest.” This is accurate to her tribe’s nomadic culture.

More Religious Diversity, Less Assimilation

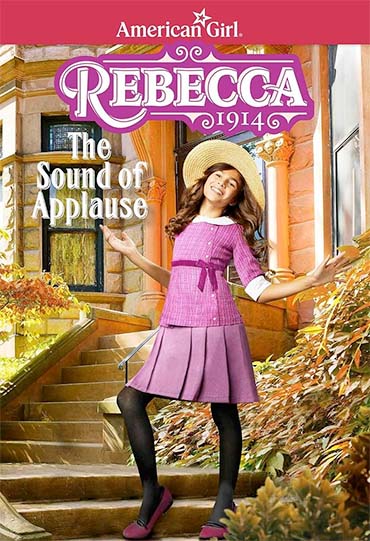

Later, American Girl explored religious diversity with Rebecca Rubin, whose stories and doll released in 2009. The seven-year gap points back to a weakness or failure on AG’s part, which we will discuss in the next section. However, Rebecca, who lives in 1914 New York, is a Jewish protagonist, the line’s first. Moreover, she is Russian Jewish, living in a multigenerational household wherein her grandparents, Bubbe and Zayde, nurture her connection to both faith and heritage. Contrast this with AG’s other immigrant character, the Swedish Kirsten, whose family tries to assimilate as much as possible.

A Saint Lucia celebration excepted, Kirsten’s Swedish culture is not explored. Rebecca, on the other hand, celebrates Hanukkah in her holiday story, and respectfully stands up to her teacher, who says all Americans should celebrate Christmas. Rebecca also celebrates Passover and her brother Victor’s bar mitzvah. She struggles not with how to assimilate, but how to honor her heritage, her faith, and the older generation she loves, while adjusting to her new country.

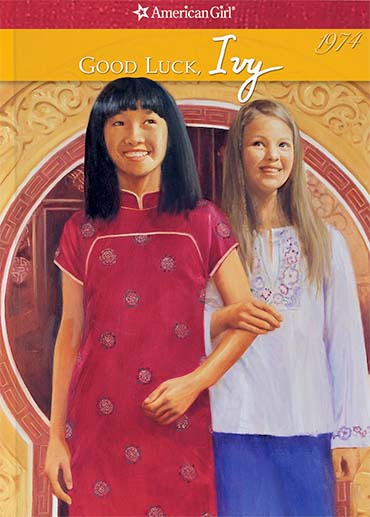

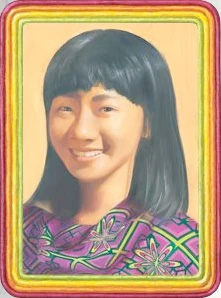

In addition to Rebecca, American Girl created Ivy Ling, “Best Friend” to Julie Albright, the 1974 American Girl, who is white. It is definitely disconcerting that Chinese-American Ivy is treated as a “satellite” to Julie, and not billed as the 1970s American Girl. However, Ivy did receive a book in the AG line proper, as well as other books and stories in lines like the American Girl Historical Mysteries. Within these, Ivy comes through as a fully self-determined Chinese-American girl.

Although her religion itself is not explored, Chinese customs and holidays not specifically tied to the “majority” religion, Christianity, are thoroughly explored. For instance, Ivy’s “holiday” book focuses on Chinese New Year, which Julie celebrates with her and in lieu of Christmas. Additionally, throughout her books and stories, Ivy deals with finding a balance between the “American” customs, food, and activities she loves, while showing equal love for Chinese counterparts. Ivy also shows healthy respect for Chinese social concepts like honor and shame, seeking to honor parents, grandparents, and family in the Chinese way.

More Focus on Situational Diversity

Finally, American Girl explored socioeconomic, familial, and other situational diversity through many historical girls created for the late aughts into the New Tens. In 2011, the company released Cecile Rey and Marie-Grace Gardner as a “Best Friends” duo, with three books each exclusively in their points of view. The girls live in 1853 New Orleans, somewhat familiar ground for American Girl. But while Marie-Grace is white, she is notably less financially comfortable than Cecile. She is also looked down on for being “American” rather than New Orleans’ more common Creole. Cecile, on the other hand, is a wealthy free Black girl whose family has been free for at least one generation. Additionally, the pairing is always rendered as “Cecile and Marie-Grace,” with Cecile receiving top billing.

Situational diversity pops up again with Julie Albright, who lives in 1974 San Francisco and is the first AG heroine with (amicably) divorced parents. Throughout her six books, Julie deals with the impact of divorce. For instance, her “school story” is titled Julie Tells Her Story. In it, Julie must decide whether to include her parents’ divorce in her assigned “Story of My Life.” Doing so would educate her classmates and remove some of the taboo from the subject. At the same time, Julie worries about being pitied or ostracized, or appearing to favor one parent over the other. Her ultimate choice to write and share about divorce communicates Julie’s arc is relatable, and that she gets to decide how divorce will impact her going forward.

Julie was released shortly before Maryellen Larkin, who lives in 1950s Florida and is a polio survivor. While Maryellen’s illness and disability are not covered as much as they could or arguably should be, she is spotlighted as a member of the line’s largest fictional family to date. Maryellen’s family has five siblings and thus, not as many resources or as much attention to go around as she’d like. At least one sister is already a young adult. This makes it harder for Maryellen to carve out her own niche, which she does throughout her books. Additionally, the presence of her “traditional ’50s” older sisters, plus her own desire to branch out into activities like rocket-building, let Maryellen explore how the definition of “American girl” is evolving in 1954.

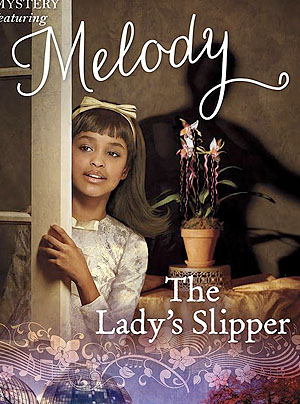

As for Melody Ellison, a Black girl living in 1964 Detroit and experiencing the Civil Rights Movement, she was released within a year of Maryellen. Like Rebecca, Melody is part of a multigenerational family; her grandparents, aunts, and uncles are not “live-in,” but constantly present. Additionally, Melody is neither underprivileged like former slave Addy, nor wealthy like 19th century free Black girl Cecile. Melody is AG’s first truly middle class heroine of color, experiencing some of the “microcosms” girls like Samantha or Molly did, alongside race-based oppression. For example, Melody explores the new roles and fashion choices of women through older sister Yvonne, who has a STEM-based job at a bank and wears an Afro. Melody participates in the Motown music scene, and though she finds Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. inspiring, he inspires her to increase her singing talent and presence while navigating the hardships of gaining more civil rights.

Historical Success: Bringing History “Closer”

The post-1998 octet gave real-life girls more protagonists, thus more opportunities to find one or more with whom they related best. Indeed, the “second generation” of AG protagonists felt “closer” and more real than their predecessors probably did. Some of the closeness can be attributed to the decades in which new protagonists lived. Before 1998, the closest thing AG had to a “modern” character was Molly, whose WWII stories were still 40-50 years removed from the late ’80s-mid ’90s reader’s experience. As the new millennium approached, that gap closed significantly. Julie was still about 30 years older than a girl reading her books in 2004. Still, most AG characters were now being released with stories set just a decade or two apart, not centuries or half-centuries. Real readers now heard, “American girls exist in all eras, and they all look and act differently.”

As they closed the physical gaps between protagonists, as well as protagonists and readers, AG also brought history “closer” through smaller character arcs across fewer books. This gave writers and characters more time to grow, and characters chances to learn from different experiences. Thus, the characters matured at different paces and in different ways.

More “Shading” in Backgrounds and Foregrounds

The post-1998 octet did eventually move away from the “grown-up background, girl-sized foreground” format of their stories. However, this was not immediate or obvious. Several protagonists in the new octet maintained these backgrounds and foregrounds with greater “shading” to bring history closer to their modern readers’ worlds and experiences.

One great example comes from Cecile and Marie-Grace. Released as a pair, these two automatically made 1853 New Orleans accessible to modern girls because they had plenty in common as best friends, but were clearly different from each other (Black and Caucasian, wealthy and lower middle-class, Creole and born in the U.S.). Furthermore, both girls’ historical event, an infamous yellow fever plague, is still lesser-known in most history books. However, the threat of sickness and death gives Cecile and Marie-Grace’s 3:3 book split the “grown-up” feel of the previous AG generation’s stories.

For instance, Marie-Grace faces some extremely adult decisions and implications when the plague means she might have to leave New Orleans for good. Cecile faces some of the same implications when illness strikes someone she loves, and when she realizes her wealth won’t make the difference she wants, to the orphans she sincerely cares about. Watching both girls weather the plague while still experiencing volunteer work, singing lessons, and friendship troubles, can help modern girls understand how “localized” historical events can impact them and change them for the better. This is particularly true in a post-COVID-19 world.

The same “shading” occurs with Rebecca, who lives in 1914 New York. When readers meet her, Rebecca has already lived in the U.S. for several years. However, her aunt, uncle, and cousins, including her best friend and “sister-cousin” Ana, have just immigrated from Russia. Therefore, readers get the “big” historical background of immigration via Ellis Island. But unlike with Kirsten Larson, whose entire arc encompassed immigration from Sweden through her first year in America, Rebecca’s arc focuses on the story of an American citizen with immigrant heritage. Ana, the “new” immigrant, provides a contrast and more potential for critical thinking.

Ana is a crucial character throughout Rebecca’s arc. In Rebecca and Ana, for instance, Rebecca becomes frustrated because her cousin isn’t learning English as fast or as well as Rebecca thinks she should. Ana ends up hurt, and Rebecca must learn to respect her journey toward adjusting to America. Through this plot, modern American readers can learn similar empathy for friends or classmates who may also be learning English, American customs, or how to execute any skills the readers take for granted.

Ana’s importance to Rebecca’s arc, and the contrast between “new” and “old” immigrant experiences, comes up again in Changes for Rebecca. Here, the “grown-up background” is the labor movement, labor strikes, and increased presence of unions common in the early 20th century. The harsh realities of these historical events hit home when Rebecca and Ana’s parents and older siblings are mistreated at work. Deciding how to respond carries a lot of weight, as speaking up or striking could make Ana’s family look like troublemakers in their still-new country, or Rebecca’s family look suspicious for supporting Ana’s family. Responding could also result in anti-Semitic backlash for the Rubins as a whole.

Rebecca uses her talent for acting to try understanding the labor movement better. However, her play unintentionally sanitizes what’s going on. Ana steps in to give her cousin a reality check, volunteering to essay the role of a cruel factory boss. Said role is the most out of character one Ana could take, and seeing it shakes Rebecca up enough to realize, what her family’s adults and teens are doing is the furthest thing from a game. Nor is it something Rebecca can easily “lighten up,” despite her unfailing optimism. Rebecca is inspired to speak out on behalf of labor strikers herself, and gets hit in the head with a rock for her trouble. Her injury is minor, but serious enough to catch adults’ attention because abuse of workers meant an innocent kid got hurt. Rebecca and Ana are hailed as heroines. As for modern readers, they stand to learn kids their age can and do face harsh realities with aplomb every day, and can and do make differences, even for the adults who face “bigger” implications than kids do.

Longer and More Impactful Arcs

Not all the new octet’s books were “shaded,” because they didn’t all follow the traditional format of Meet, Learns a Lesson, Surprise, Happy Birthday, Saves the Day, and Changes. For those book series that did not, the historical arcs remained, but were commonly broken up so readers could follow one “bigger” adventure through several “smaller” installments. The format did not always succeed 100%, but when it did, American Girl and its new protagonists received much-needed freshness. Similarly, modern readers got opportunities to plumb certain historical periods in more depth.

The first new octet American Girl to do this was Caroline Abbott, from 1812 New York (Sackets Harbor, as opposed to Samantha’s upstate Mt. Bedford or Rebecca’s New York City). In Meet Caroline, our heroine’s beloved Papa is taken prisoner in the War of 1812, and Caroline promises to be brave until he can return. However, Caroline doesn’t go on to live a relatively safe “home front life” as Molly did in WWII. Nor is her life impacted by but largely separate from the war as Addy’s was in 1864, when the Civil War was a year from ending. Instead, in her first book, Caroline lives through a British attack on Sackets Harbor. In other words, Caroline faces the possibility that those close to her will be injured, taken prisoner, or killed. The War of 1812 is real to her from minute one of her character arc. She must contend with it regardless of her age, sex, and innocence.

Had Caroline been a first-generation AG character, she might have survived the attack in her “Meet” book and then gone on to live a “normal” life until reunification with Papa in book six (a la Addy or Molly, or Felicity and Josefina, who both face the possibility of beloved friends and relatives leaving in their final books, but until then, don’t undergo significant change). Indeed, Caroline experiences some “normal” periods and girlhood travails, such as when she clashes with a cousin and friend who would rather “stay inside and style hair” than sail and climb trees as she likes to do. However, Caroline spends most of her books taking an active role in the War of 1812. Sometimes with her mom, sometimes on her own, Caroline visits her dad in prison, acts as a courier for secret messages, and uses her wits to outsmart British sympathizers.

Given that the closest thing modern readers had to Caroline’s war took place in the Middle East, and given that incarceration looks much different in the modern U.S. than in 1812, most of Caroline’s readers couldn’t relate on a personal level. Yet, experiencing this multi-book adventure with her likely made readers tap into courage and confidence. It may have inspired them to learn more about Caroline’s era, and seek to make a difference for people in tough situations how they could (e.g., writing cards and letters to soldiers overseas, raising awareness of abused groups such as trafficked children).

Melody Ellison from 1964 Detroit has a similar multi-book arc, although her books came out streamlined in a 3:3 format as part of the BeForever line. Melody doesn’t undertake a six-book adventure like Caroline, but all her books focus to some degree on her singing talent, how she will use it, and what kind of adult she will grow to be in an era where opportunities for Black women were increasing, but not without a fight.

Melody does not “learn a lesson” in a “school story” as her predecessors did. But she does use her voice to stand up in school and say the Pledge of Allegiance does not inherently include Black people, based on how Blacks are treated, even in the North. Therefore, the Pledge is a lie, and Melody is willing to face repercussions for insisting such. Melody is not a victim of a church bombing or injured in a Civil Rights protest, but she does go to the bank where her qualified older sister was turned down for a position based on race. She threatens to close her account and tell others to do so, too. She does find the church bombing so emotionally traumatic, she goes temporarily mute.

Melody’s books maintain these callbacks to Civil Rights or related events through six plots. When Melody and her friends decide to clean up a local playground and make it safer, Melody is placed in charge of the project. She learns how difficult leadership can be, and this is treated as a microcosm for Civil Rights leadership as she and her classmates face race-fueled opposition, as well as doubt and opposition from some of the adults they expected to support them.

Throughout six books, Melody also enjoys activities like listening to Motown music and experimenting with different fashions and hairstyles. But she also faces obstacles like supporting older brother Dwayne when their parents disapprove of his musical ambitions, or being accused of planning to steal just because she went into the “wrong” shop.

As noted, this arc is not as “big” or adventurous as Caroline’s, which has garnered some deserved backlash. Melody as a character and doll has also gotten some backlash because as a ’60s Black character, she still appears with straightened hair in all her pictures and merchandise, and never with glasses, although her short Amazon movie showed her actress in glasses and braids. Finally, Melody never received six separate books, which seems suspicious alongside her race, perpetually straight hair, and arguably “too small” plot in the face of the Civil Rights Movement. This said, Melody does maintain a “shaded,” six-book arc with a grown-up/girl-sized format, which brings the “grown-up” issues closer to young readers.

Historical Failure: Uneven Highlighting and Erasure

Along with the successes of the new characters, American Girl experienced some weaknesses in their historical line. Some of these were outright failures, depending on who was being asked. Weaknesses or failures though, the negative elements combined with the new septet’s positive developments created a “mixed bag” for girls enjoying the AG brand after the 1998 Mattel buyout, as well as their parents and guardians.

Oddly Constructed New Lines

Post-Mattel buyout, American Girl created the short-lived “Best Friends” line, wherein a “main” American Girl’s best friend received a doll and 1-2 books each. Among the “Best Friends” were Felicity’s friend Elizabeth Cole, Samantha’s friend Nellie O’Malley, Kit’s friend Ruthie Smithens, and Molly’s friend Emily Bennett. “New” American Girl Julie also received a “Best Friend” in Ivy Ling, and as noted, Cecile and Marie-Grace were released together as a “Best Friend” pair. This puts the “Best Friends” count at 7. They are on “equal footing” with the “main” American Girls in terms of raw numbers. Plus, the Friends line does give interesting, new historical characters “top billing” and increased character development.

Successes Eclipsed With Failures

The “Best Friends” line does succeed in significant ways, especially exploring new points of view. “Main” American Girl Felicity Merriman is a staunch 1774 Patriot, but her best friend Elizabeth is a Loyalist. Thus, giving Elizabeth a story of her own communicates Loyalist leanings could be positive; Elizabeth is not a “bad guy” or “on the wrong side of history.” Elizabeth also gets some much-needed character development that the other Best Friends don’t necessarily receive. In Elizabeth’s case, she has always been the rule-follower and more cautious in the friendship pair. Yet in her book Very Funny, Elizabeth, she gets to question what a “proper young lady” should do and how she should handle problems like bullying. Elizabeth’s choice to stay within the bounds of propriety while still being assertive, communicates one need not be a bold or tomboyish girl like Felicity to get what one needs or wants.

“Main” American Girls Samantha Parkington and Kit Kittredge are experiencing the “major” socioeconomic landscapes of their time periods. Samantha experiences wealth in the genteel Edwardian Era, while Kit experiences the common deprivations of the Great Depression. But their best friends Nellie and Ruthie experience the respective opposite economic situations. Nellie has lived the economic, physical, and emotional hardships of being an Irish immigrant in Edwardian New York City. These include child labor, constant worries about money and health, and eventually, a harsh orphanage and the danger of being permanently separated from her younger sisters. Samantha’s wealthy aunt and uncle adopt all three girls at the end of Changes for Samantha. It’s clear though, that their choice is unconventional for New York “society.” At times, Nellie’s gritty experiences continue “bumping against” Samantha’s more idealistic life. More often than not, Nellie struggles to fit into Samantha’s world and distinguish herself as more than Samantha’s formerly impoverished friend.

In contrast, Ruthie’s life went largely unchanged when the Depression hit because her dad is a banker. She enjoyed several privileges Kit lost, such as fancy clothes, extravagant Christmases and birthdays, and dance or ice-skating lessons. Granted, Kit never enjoyed dancing or ice-skating. But Ruthie’s abundance still rankles when Kit compares it to her life. Kit has to share her house with boarders, give up her room, wear hand-me-downs, and face realities Ruthie likely won’t, such as when she encounters her dad in a soup kitchen line. In fact, Kit and Ruthie experience a fallout in Kit’s Surprise because Ruthie constantly offers Kit “charity,” or implies Kit’s family is unhappy without her privileges. Ruthie means well but honestly does not understand she’s harming Kit’s dignity and insulting her family.

Whenever the “main” AG protagonists encounter problems like these alongside a friend, the series gets to explore the deep bonds common to girls’ friendships across eras, races, religions, socioeconomic backgrounds, and more. It is a shame then, that the Best Friends line was completely retired after only a few years, and that it received lackluster reception while it existed. If anything, many parents of AG fans felt the Best Friends were an excuse to create and sell more dolls, thus feed Mattel’s bursting coffers. The Best Friends line in particular ironically fed the materialism Pleasant Rowland sought to avoid with her original American Girls. Unfortunately, materialism was not the only problem Best Friends, the post-1998 historical octet, and the AG characters following, would face.

Creating, Then Erasing, Developed Diversity

The Best Friends’ handling of their characters and plots is far from perfect. As noted, the Best Friends only receive one, at most two, books in which to encapsulate their entire personalities and arcs. If anything, some of those stories still read as “satellites” to their “more important” friends. Emily Bennett’s arc, for instance, revolves around her adjusting to an American school while living in the States to escape London bombings. She learns to stand up for herself in the face of teasing and unfair treatment, but only with support from Molly. This can read as Americans “rescuing” the beleaguered British in a WWII microcosm. It can also read that, because Molly is the American in a majority-American environment, her culture and customs are more acceptable than Emily’s. Therefore, Emily should make an effort to assimilate before or instead of American kids making an effort to accept her.

A similar problem pops up with Ivy Ling. Again, her culture and customs are given a lot of respect in Good Luck, Ivy, her “Best Friends” book. Yet as YouTube channel Dream Studios points out, Ivy’s conflict over whether to attend a gymnastics meet or spend time with her family seems odd for a plot meant to take up a whole book. Besides that, Ivy’s father supports her attending the gymnastics meet, causing friction between Mom and Dad over an “American” activity vs. a “Chinese” one. The “American” activity is chosen, thus privileged.

While this does highlight Ivy’s struggle with balancing two cultures and countries, that struggle is somewhat lost when American culture comes out ahead. Plus, as Dream Studios notes, it would’ve been easy to give Ivy a plot centered on the large historical implications of being Chinese-American in 1974. Such a plot would not have to be overly positive or revolve entirely around marginalization. However, the fact that Ivy’s author, Lisa Yee, did not choose such a plot seems odd. If Yee was told or pressured to write Ivy’s book as-is, it reads like oversimplification of who Ivy is.

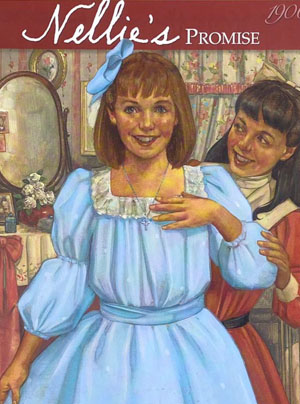

Finally, the “uneven highlighting” of certain situational diversity can be found between Samantha and Nellie. Nellie’s book, Nellie’s Promise, focuses on the adoption of Nellie and her younger sisters, Bridget and Jenny, into Samantha’s family. The adoption is threatened when Nellie’s abusive Uncle Mike shows up and lobbies for custody of the girls. The plot itself has good “bone structure,” in that Samantha, Nellie, and Samantha’s family drive home a pro-family, anti-prejudice message. But the stress of the situation tests the girls’ friendship, such that one Amazon reviewer complains, “the book focuses on their differences more than anything else.”

The reviewer went on to say by the end of Nellie’s Promise, the girls live together but “basically lead separate lives.” The plot of Nellie’s Promise, then, as well as other Samantha-centric books like The Curse of Ravenscourt, keep the girls in their standard “molds.” That is, Nellie exists to “educate” Samantha on the realities of those who have different nationalities or financial backgrounds than she does. For her part, Samantha looks like Nellie’s constant “savior,” as in Samantha Learns a Lesson, wherein Nellie only gets a decent education from Samantha’s tutelage. Failing that, Samantha reads as someone who would say something like, “Some of my best friends are poor” in order to excuse innocent but real ignorance.

Highlighting the Visible, Erasing the Invisible

Series-Wide Crisis of Faith

Along with diversity erasure, American Girl’s historical line, particularly the main one, tends to highlight visible differences while erasing invisible or less visible ones. The problem comes up most often in cases of religious, ability-based, or personality and plot arc diversity. For instance, Rebecca Rubin is Jewish, gets six full books (two with three edited stories in the BeForever incarnation, as does every American Girl in that line). She does celebrate Hanukkah, bar mitzvahs, and similar occasions.

But of the post-1998 group, Rebecca is the only one with an overt religious background. Worse, outside her Hanukkah story, Rebecca’s faith is usually eclipsed. Her stories focus more on how she is pleasing or displeasing her family in adjusting to America. Again, that’s a great plot thread, particularly when compared to Kirsten, Emily, and Nellie, who are expected to assimilate. Yet since Rebecca is the only Jewish protagonist in over a decade, pulling her faith out of focus is strange and unfair.

Other AG protagonists experience this “crisis of faith” too, as writer Rachel Milkaszewski of AltFem Magazine points out. Milkaszewski, herself a practicing Catholic, writes that from 1998 forward, none of the girls who might come from a Christian background, acknowledge or portray this. Milkaszewski congratulates AG for portraying girls from all possible faith backgrounds, but notes “there hasn’t been a doll with a Christmas story since 2000,” and that protagonists like Caroline, Cecile, Marie-Grace, Melody, and Maryellen do not reflect the Christianity they likely would’ve embraced in their eras.

Melody, for instance, attends church regularly, but mostly to sing, and one of her stories focuses on the infamous bombing of a Birmingham church. Melody is understandably traumatized and uses her musical talent, based on faith, to cope. Additionally, it’s natural to focus on the bombing because the victims were near Melody’s age. Yet some readers and adult fans felt a church bombing was an odd choice considering the other tragedies that took place during the Civil Rights Movement, many of which also directly harmed, killed, or otherwise affected children. Other protagonists who would likely come from devout families, like Cecile and Marie-Grace, barely mention their faith (despite the fact both girls spend entire books working at a Catholic orphanage and interacting with nuns).

If, as Rachel Milkaszewski says, “Christianity is disappearing” from American Girl, then, Judaism has already disappeared, and other faiths are not even offered a place in the historical line or its offshoots. For instance, Ivy Ling is said to celebrate Chinese New Year, but this is not a religious holiday, nor is Ivy’s faith ever mentioned. Instead, Ivy is written “coded” Christian, as if she and her family might have given up a faith like Buddhism, Taoism, or folk religion to assimilate. The main historical line of AG has no Muslim, Shinto, Sikh, or folk religion followers, nor do plans to create them exist. And while most protagonists are at least “coded” Christian, AG’s outright refusal to acknowledge certain forms like Catholicism, even when said forms would be ubiquitous, is discouraging.

Faint But Present Ableism

Another group American Girl tends to erase or downplay in its historical line is disabled protagonists. Within the historical line, disability appears thrice, with Kaya’s adopted sister Speaking Rain, “main” protagonist Maryellen Larkin, and Julie Albright’s friend (not “Best Friend”) Joy Jenner. Speaking Rain is blind. Maryellen is a polio survivor. Joy is deaf (often rendered Deaf out of the community’s desire for regard as a culture). Kaya and Speaking Rain’s tribe and culture did not use “disability” as a concept, much less “disability accommodations,” and probably would have treated Speaking Rain’s blindness as natural. Both Maryellen and Joy live in eras without the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) or Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The latter barely existed in 1974, while the former wouldn’t exist for 16 more years. It makes sense then, that they would face outright bigotry or ingrained ableism (e.g., no accommodations offered in school, few or no accessible venues).

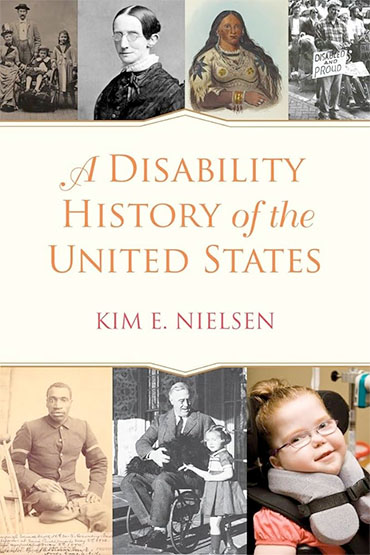

At the same time, disability is clumsily handled across all these characters’ storylines, if not by their communities, by the authors of their books. This starts as early as Kaya’s stories. Yes, Speaking Rain’s blindness is not ridiculed. If anything, the real Nez Perce tribe could have viewed blindness as a conduit of Speaking Rain’s abilities and gifts. Alternatively, they could have simply accepted, “Speaking Rain can’t see, so she does non-visual tasks that help our community,” an attitude Kim Nielsen hints at in her book A Disability History of the United States. Better, the orphaned Speaking Rain is accepted into Kaya’s family as her sister, with much more equality and smoothness than Nellie, Bridget, and Jenny were accepted into Samantha’s.

But while Speaking Rain doesn’t face ableism as such, she does get victimized or erased. Kaya loves her and treats blindness as a matter of course. Yet she also focuses on how much Speaking Rain can’t do at times, or how much the other girl will slow her down, as in Kaya’s Escape. During that book in fact, Speaking Rain gets left behind with an enemy tribe while Kaya sets out alone. It’s clear the tribe won’t abuse Speaking Rain, and in truth, Speaking Rain urged Kaya to go without her so she wouldn’t be a worry. Yet in the 21st century, a disabled character saying this, plus being left in enemy hands for several more books, never to be heard from, reads odd at best. The fact that Speaking Rain is a secondary character and secondary friend to Kaya (as opposed to say, Swan Circling), highlights the disparity more.

As for Maryellen and Joy, they don’t simply deal with accurate systemic ableism. Both their disabilities are almost entirely erased or “othered.” In Maryellen’s case, her survivorship is mentioned throughout her books. Yet, Maryellen can walk, breathe, and move as well as any child who did not contract polio in 1954. Her disability is never mentioned as part of her personality or what she’s passionate about. Instead, Maryellen is painted as a tomboyish “Academic Athlete” type of girl whose biggest ambitions include breaking out of her middle child role and “being the hero” like her television heroes The Lone Ranger or Davey Crockett.

Thus, Maryellen is “coded” abled. The one exception appears to be in her short Amazon movie, where she reminisces about having polio and participates in March of Dimes. Even more discouraging, March of Dimes is an organization many disabled people and their allies now find problematic. Most of the money the organization raises does not go toward helping disabled people in any way, much less living the autonomous life Maryellen does. March of Dimes’ mission revolves around “prevention and cure” of disabilities, which made sense in the days of incurable polio but is now outdated and tone deaf.

Joy’s case comes off even worse. She only features in Changes for Julie, wherein Julie runs for class president and picks Joy as her vice-president. Julie’s choice incites bigotry from a clique called the Water Fountain Girls, who routinely mock sign language and Joy’s voice without reprisal. The student body, excepting Julie, casts aspersions on Joy’s ability to hold any student government position, and the girls’ teacher Ms. Duncan regularly penalizes Joy for doing things like whispering in class. Ms. Duncan is never told Joy does this so she can follow along in a hearing classroom wherein she’s not accommodated. Nor does this problem ever occur to the teacher, and nor does Joy ever receive an apology for being unjustly punished.

Julie and Joy do “team up” to show two girls, one of whom is ability-diverse, can lead fellow students and positively impact their school. Their actions result in the Water Fountain Girls getting held accountable. But in the case of the Water Fountain Girls, Julie volunteers Joy to give them sign language lessons so they can “understand” deafness better (Julie participates, but secondarily). Additionally, Julie’s focus is more about coming up with an alternative to Ms. Duncan’s traditional sentence-writing punishment, than increasing Joy’s acceptance. Couple this with the fact Julie, not Joy, campaigns actively for her government position, and wins the “bigger” position in the bargain, and it looks as if Joy, thus disabled people, must always be secondary or subordinate to abled people.

Altogether, Changes for Julie starts reading as if Julie used Joy, who was never seen before or since, to further her own ambitions. Yes, Julie is doubted and marginalized because she’s a girl, but wins support from girls and boys in her campaign. The message, then, becomes, “Yeah, but at least Julie’s abled.” It comes across as another cheap shot. Joy, on the other hand, becomes a conduit of inspiration porn who might well not succeed or have friends without an abled girl’s support. Her quieter, more cautious nature and her alliterative name alongside Julie’s makes Joy seem like a last-book afterthought.

Smaller Problems and Plots

The post-1998 octet’s plots and personalities are sometimes, if not often, successful. Some storylines maintain the format of “grown-up background inside girl-sized foreground,” and the accompanying microcosms. Cecile, for instance, gets to explore her opera-singing talent, artistic bent, and future as a free Black girl inside the background of the 1850s, an era in which modern children are unfortunately often taught, most Black people were enslaved. Melody’s books make clear that the Civil Rights Movement, while seen as “grown-up,” had a powerful impact on kids, such as when Melody experiences trauma from hearing about the church bombing or speaks out that, “The Pledge of Allegiance is a lie!” Kaya’s personal struggles with competitiveness, impulsivity, and carelessness provide a microcosm for how she fits into the Nez Perce tribe.

That said, many of the post-1998 octet’s plots come off as “smaller” and “easier to digest” than fans of the original quintet/septet remember. Failing that, they come off as recycled. Maryellen’s determination to get her share of attention as a middle child is relatable, but feels incongruous when it’s allowed to take up almost her whole “Meet” book. Kaya’s inner battles can be “big” and heartbreaking, such as when her actions cause the tribe’s Whipwoman to punish innocent kids, or when she loses her adopted sister and a pet she loves.

In the absence of an overarching historical event though, Kaya’s books often read as if she is put-upon or even unjustly, unnecessarily abused. And while Rebecca does deal with some intergenerational struggles and anti-Semitic attitudes (Hanukkah treated as un-American), her near-constant focus on movies and playacting through her second three books can make her come off as overly naive or spoiled. Plus, her desire for attention as a middle child makes it seem as if she and Maryellen are recycling each other’s personalities.

Finally, despite the continuation of gravitas, the post-1998 octet’s plots and personalities slowly began becoming “smaller” and “easier” than the original quintet/septet’s. The change began with the BeForever historical line revamp, which had already received backlash for retiring almost all of AG’s original characters and some newer ones, including Addy, Josefina, and Cecile. In the BeForever line, not only were AG’s diversity ratios way off again, but the “old” characters’ adventures were abridged and streamlined.

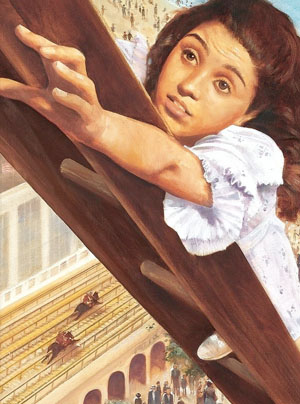

Meanwhile, with notable exceptions, “new” characters did not face the same caliber of coming-of-age problems previous ones did. Rebecca, for example, does learn valuable lessons about what being “American” means as a second-generation Jewish immigrant, and she does gain a mature perspective on current issues like labor strikes. But her summer “to the rescue” story hinges on rescuing her (conveniently) timid cousin Ana from the top of a Ferris wheel, rather than say, helping a friend make a life-changing decision as Felicity did, or learning the “idyllic fantasies” of someone else’s life don’t stand up to reality, as Kit did.

Similarly, Julie experiences “pioneer life” through a camping weekend, but her plot is more about how she, a 1974 girl, must adjust to temporary deprivation than how the experience will help her come of age. And while 1954 is peacetime for the U.S., Maryellen’s books barely mention the Cold War. When they do, the stories read as if Maryellen “teaches” her class about it, when in reality, her classmates would’ve been extremely familiar with the stakes, thanks to the news, “duck and cover” drills, and so forth.

Continuing Challenges for the Newest Quintet

After the introduction of Julie Albright, it seemed American Girl’s historical line had reached its conclusion. After all, 1974 was just under a decade from the company’s original inception and just about 30 years from when the current generation of girls would be reading Julie’s books. Girls eyeing new dolls, outfits, and accessories could now recognize “historical” fashions and playthings as items their moms, aunts, and grandmas once wore or played with, perhaps still owned. But surprisingly enough, the AG historical line did expand after Julie. Sometimes it added to decades past, but sometimes, the “time machine” kept pushing forward. As with the post-1998 octet, the results proved, are still proving, a mixed bag.

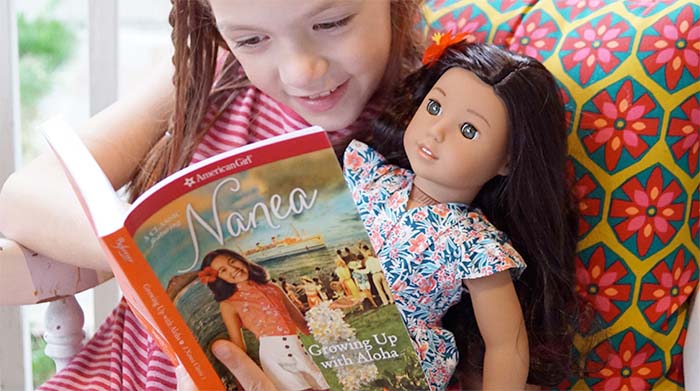

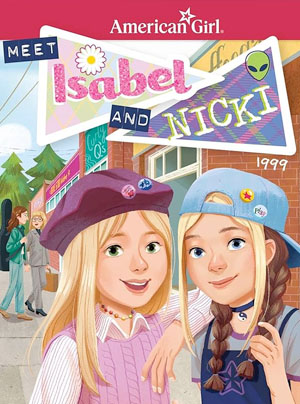

Currently, the newest heroines make up a quintet: Nanea Mitchell, Courtney Moore, Claudie Wells, and Isabel and Nicki Hoffman (fraternal twin sisters, released together in 2023). Nanea has the earliest release date of 2017, but can be considered a “late Tens/2020s” doll, while Courtney, Claudie, Isabel, and Nicki were all released between 2020 and 2023. Additionally, while Nanea is from 1941 and Claudie from 1922, Courtney, Isabel, and Nicki are from 1986 and 1999, respectively. In other words, the eras of original AG fans are now considered “historical,” a decision that has sparked plenty of online ribbing and not a little controversy.

That is, bringing “historical” heroines from such recent decades on board could open up new opportunities for AG’s historical fiction authors and doll designers. At the same time, it means the historical line may not have anywhere else to go. Since historical fiction is the foundation of the brand, this may signal AG has burned itself out. Either way though, the newest historical quartet has faced, and will face, challenges their 15 predecessors never did.

The Incongruity of Nanea

The first challenge for this New Tens/2020s quintet unfortunately lies in its first historical protagonist, Nanea Mitchell. A half-Hawaiian girl living in 1941, Nanea lives through Pearl Harbor in real time. Therefore, she has a better and more mature grip on WWII than did Molly McEntire, whose stories took place in the 1944 Midwest as the war was ending, and whose attitude often revealed how sheltered she was. Additionally, Nanea’s story is unique in several small, but significant ways. She is the first American Girl not from the Lower 48 States. She is also the first mixed-race, mixed-heritage historical heroine, with both Hawaiian and Scottish roots. Finally, unlike Addy, Melody, Kaya, and other protagonists of color, Nanea has white friends who are secondary to her, rather than the other way around. Therefore, strong arguments exist for Nanea’s stories being needed in the AG canon.

At the same time, Nanea’s incongruity cannot be ignored. Since her release, many adult fans from both sides of the political aisle have taken to social media to ask why AG added Nanea, a World War II heroine, when Molly already existed. Some fans claim Nanea looks too much like a Wellie-Wisher, one of the contemporary dolls aimed at younger girls ages 5-8. Still others claim Nanea was released too closely to contemporary characters Corrine and Gwynn, who are Chinese-American.

These questions and accusations gave rise to some uncomfortable discussions, such as whether Molly fans were racist or whether American Girl was trying too hard to capitalize on a heroine “type” they had already created several times over. With only social media anecdotes to go on, nothing can be proven one way or the other. However, while the protest, “But Molly exists” is definitely petty, the argument could be made that Nanea, more than most historical protagonists, was made in response to certain trends, or even mistakes AG made in the past. For example, the children’s, young adult, and adult literature markets were bursting with WWII fiction in 2017 and continue to burst, so it’s not out of line to wonder if Nanea was some form of a response to that.

Additionally, the release of Nanea alongside the Chinese-American Corrine and Gwynn reads like a response to the quick retirement of Ivy Ling. The Best Friends line and AG as a whole received bad press for this initially, and continues receiving it on social media, such as through YouTube channel Dream Studios.

The strangest thing about Nanea though, is her historical date compared to those of the dolls released closest to her, on either side. It’s true that Maryellen and Melody, released in 2015 and 2016 respectively, are a mere decade or two younger than Nanea. It’s also true that Claudie, released in 2020, is just about two decades older than Nanea. Courtney however, who was released three years after Nanea, is 45 years younger, and Isabel and Nicki over 50 years younger. This means Nanea is as far removed from some “contemporaries” as Molly was from her original readers. The fact that Nanea and Claudie are the only two “truly” historical characters in the newest quintet, and are only two decades apart, does not help Nanea’s case.

The detachment between Nanea, Claudie, and the rest of the most current quintet gives unfortunate credence to the idea that Nanea was created to cater to trends. It also disrespects Nanea’s author Dorinda Nicholson, who lived through Pearl Harbor herself at age six. Thirdly and perhaps most disturbing, the release of Nanea three whole years before Claudie’s release, gives credence to the idea of both dolls, heroines of color, being created as not only trend responses, but tokens. Had there been just one or two more protagonists from eras closer to Nanea and Claudie’s, no matter their race or background, this might not be an issue. But in creating a mixed-heritage Hawaiian girl, waiting three years and the turn of a new decade to create another Black girl, and allowing detachment from the other 2020s girls, AG has set itself up for controversy yet again.

But more discouraging than Nanea’s detachment from the dolls released alongside her, and the rest of the line, is how repetitive her arc feels. Granted, her character and stories themselves are unique. Nanea, for instance, must face the possibility of an older brother, a kid near her age, going to war instead of a parent. She grieves when her best friend must leave Hawaii for good, and like Caroline, she lives with the realities of wartime every day. In fact, Nanea can’t recover “normalcy” no matter how hard she tries, a feeling any girl who remembers the pandemic can identify with.

Still, Nanea’s author and other creators have stated the purpose of Nanea’s coming-of-age story is to teach “resilience, responsibility to others, and contributing to the common good.” These lessons were not only already present in Molly’s WWII stories, but can be found across eras in all the other protagonists’ books. This is not necessarily negative, as it hearkens back to the idea of timeless emotions and experiences Pleasant Rowland sought to convey. But considering Nanea’s era is somewhat a repeat, and rather detached from the decades AG had most recently explored before her release, it feels a bit stale.

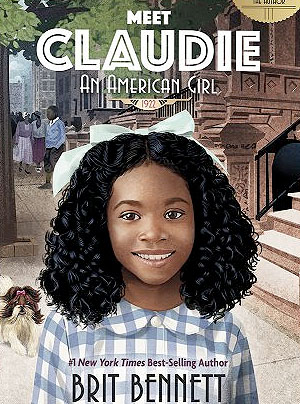

The Strange Placement and Treatment of Claudie

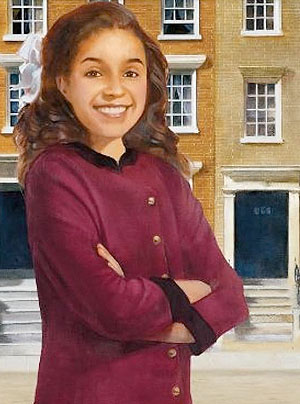

Stale or not, perhaps Claudie Wells could redeem Nanea and her odd placement in the historical line alongside three ’80s and ’90s girls. Claudie has indeed broken new ground, not only for American Girls of color but the historical line as a whole. Like Cecile and Melody, she is a free Black protagonist, but being from a lower middle-class family and 1922, is more likely to face race-based oppression than her predecessors, without the backdrop of coming civil equality.

However, Claudie also grows up in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance. Black artists, writers, dancers, and actors surround her, and her stories focus a lot on how Black culture grew and thrived during Claudie’s time period. In other words, oppression is not ignored, but it is not the impetus for all of Claudie’s growth and maturity. That tends to come from Claudie’s experiences within her family and neighborhood. Because these happen alongside the “birth” and “rebirth” of her community and city, Claudie’s coming-of-age arcs feel more mature than similar ones from heroines like Maryellen and Julie.

Claudie also has a locus of devoted fans, mostly based on her appearance and collection of outfits and accessories. To wit, Claudie has textured hair, but is also the first Black AG protagonist to wear it down and curled, not only in book illustrations but as a doll. For many adult fans, this clearly communicates their daughters can and should embrace and enjoy natural hair in all styles. Additionally, Claudie loves fashion, and her clothing reflects that interest. Her outfits include a mint green winter coat and beret ensemble, two jazz-inspired outfits filled with sparkles, and an age-appropriate flapper outfit with a faux fur stole.

Most of Claudie’s outfits include some form of hat, usually beribboned or sporting accessories like pompoms. Her sleepwear, a pair of sunny yellow pajamas, includes a purple sleep bonnet Black girls of her time, and Black girls today, might wear to preserve their hairstyles. When compared to other Black protagonists’ collections–Addy’s “plainer” outfits or Melody’s outfits and hair, which still hearkened back to “white” ’60s trends–Claudie’s collection embraces Black culture and vibrates with Black joy.

Considering her groundbreaking moves and vocal fan base, it’s a shame Claudie has fallen into a trap similar to the one set for Nanea. That is, her small base aside, Claudie hasn’t received nearly the attention of her historical predecessors, or even fellow quintet-dwellers like Courtney. American Girl’s choice to release a 1920s girl after a 1940s one, means Claudie feels a bit “displaced” in the most recent batch of historical characters. It’s easy for her to slip through the cracks, and when she is remembered, it sometimes takes looking at her outfits to remember what era Claudie comes from. Where Nanea seems to “cut into” the historical line then, Claudie feels unjustly invisible.

Worse, Claudie is the first “truly” historical American Girl to receive only one book so far. Titled simply Meet Claudie, the book appears to be a primer on Claudie, the Wells family, and Claudie’s world, as are all other “Meet” books. But from the Amazon summary, Meet Claudie reads as a streamlining or abridgement of several books or plots, without the benefit of BeForever branding or the explanation of 3:3 retooling. Claudie comes across as only getting, maybe needing, one story for real girls to know and understand her. Considering Claudie’s race and background, plus the possibilities that should have been explored in her era, these choices make the AG brand look quite suspicious.

Finally and most discouragingly, Claudie’s story might have the lowest stakes of any historical protagonist American Girl has created. Amazon does not allow viewers to “look inside” Meet Claudie, so most information must be gleaned from promotional materials. From there, readers learn Claudie’s major arc focuses mostly on “finding her thing.” In other words, growing up in the Harlem Renaissance has made Claudie feel she is the only person she knows without some special talent. She “tries on” different talents, and is able to use some of these in larger coming-of-age plots, such as saving her family’s beloved boarding house from closure.

Remember though, Rebecca Rubin also grappled with her theatrical talent’s place in her life, once using it to raise funds for her family (and earning a scolding). Maryellen Larkin spent almost every story in her collection trying to extricate herself from the “middle child” label and prove she could be “in charge.” Like some other protagonists then, Claudie falls prey to recycled plotlines and weak coming-of-age arcs. As with Rebecca, Claudie’s fixation on “finding her thing” ends up reading less as determination and more as childish naivete.

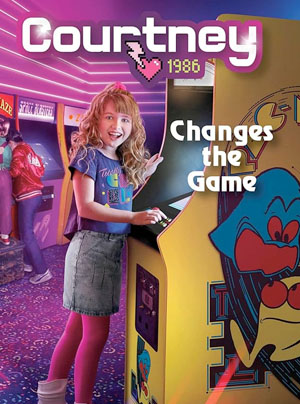

The Mixed Reception of Courtney

If Nanea is too detached from her contemporaries in doll world, and Claudie is placed too oddly to attach at all, Courtney, Isabel, and Nicki may be much too close to their readers’ worlds. Their releases in 2020-2023 have ushered in a definite new era for American Girl. Plenty of interesting questions exist regarding where the franchise can, will, or should go from here, and many of the potential answers are undeniably exciting. But it cannot be denied, the initial reaction to Courtney’s release, and later Isabel and Nicki’s, the “’90s twins,” was unadulterated shock–and not the good kind.

“Courtney Moore is from 1986. 19-FREAKING-86,” a Twitter (now X) user exclaimed upon the ’80s American Girl’s release. The tweet touched off thousands of others as former AG fans, many of them current parents and guardians to new fans, “flocked” to social media to vent. “I’m officially old” was a common refrain. This writer, herself born in 1986, got in on the fun, posting a meme from Freaky Friday wherein Jamie Curtis exclaims, “I’m like the Crypt Keeper!” But fun aside, plenty of AG fans stopped laughing long enough to ask, “Is 1986 really ‘historical?'”

Of course, 1986 is now almost 40 years in the past, so “old” jokes aside, skepticism surrounding Courtney died down fairly fast. Like many earlier American Girl stories, Courtney’s unites “localized” issues with national ones (e.g., Courtney’s desire to prove herself among her male gamer friends, one of whom has AIDS. His experiences nudge Courtney to educate herself and others). Courtney also comes alongside Julie as a child of divorce, as well as the first American Girl from a blended family, still a novel concept in the mid-’80s. Her passion for gaming, united with passions for activities like shopping at the mall and collecting Strawberry Shortcake merchandise, tells real girls it’s great to be well-rounded. A girl who enjoys STEM need not be wholly focused on math and science; she can channel her interests into game and graphic design. A girl who loves pink and uses what was termed “Valley Girl slang” in Courtney’s era is not vapid. And while a real girl’s family may not be “perfect,” as seen in ’80s sitcoms, that family can be perfect for her.

Still, Courtney’s good messages got eclipsed and found some more detractors with the advent of the Hoffman twins, Isabel and Nicki. The sisters are ten in 1999, placing them smack in American Girl’s heyday. Their collections and promotional materials often picture mock-ups of early AG webpages, and AG commonly references itself in the Hoffman sisters’ books. Therefore, along with more good-natured ribbing about original fans aging, there are now legitimate questions about what AG’s historical line is doing as a whole. In creating Isabel and Nicki, the line and franchise may have burned itself out. At the least, the twins’ collections and plots show they’ve run short on ideas.

The “Nearsightedness” of Isabel and Nicki

Like Courtney, Isabel and Nicki have several strong points. The nostalgia factor of their stories aside, plenty of historical 1999 issues provide discussion fodder for current AG fans and their families. For instance, Nicki is terrified of the Y2K bug, even though Mom is a coder and has reassured her daughter she is working hard to find solutions. Isabel falls prey to “mean girl” behavior from her friend group, a precursor to the heightened awareness of bullying that would overtake news outlets in coming years.

In addition, Nicki and Isabel are the first American Girls from an interfaith household (Dad is Jewish, Mom is Christian). They’re the first pair of historical girls whose personalities receive equal footing. (In past matchups, such as Felicity and Elizabeth or Molly and Emily, the “main” American Girl was usually the more extroverted, excitable, or leadership-minded. Here, cautious Nicki gets as much page time and character development as bubbly Isabel). Plus, while readers might expect introverted Nicki to be the “girly twin,” she’s a tomboyish skater. Extroverted Isabel is more “girly,” though her tennis skills mean both girls are athletes and subvert the stereotype that girls who like sports are “tomboys.” The switch from the “expected” is even reflected in the twins’ pets. Isabel prefers cats, who are often seen as “quiet” pets, while Nicki is a dog-lover.

Releasing the Hoffman twins together and letting them buck stereotypes, or at least expected likes and dislikes, was a strong move on American Girl’s part. Isabel and Nicki brought back the potential character depth of the Best Friends, without shortchanging one heroine or another. Making the girls close sisters while giving them clear, contrasting interests also lets real readers identify with both in different ways. (This writer is herself an “Isabel” in that she loves cats and would’ve loved Isabel’s tailored-yet-sparkly style. Yet she is a “Nicki” in that she’s an introvert, a writer, and a music-lover who prefers gaming to the athletic field). Still, it’s clear from reading the Hoffmans’ one story that they are the most “nearsighted” of AG’s current quintet. One could argue they are not historical at all, no matter that the ’90s are now 30 years in the past. One could even question why these characters exist, in view of the Just Like You dolls that were released in the ’90s and the Create Your Own and Truly Me dolls that have been offered since.

Isabel and Nicki do not get an arc like their predecessors, even if those predecessors, such as Nanea and Claudie, received only one or two books. They get one story set on New Year’s Eve, 1999, which packs several events into a limited number of chapters. With the exception of Nicki’s Y2K fear and the millennium celebration in their hometown of Seattle–later cancelled for fear of the same bug–none of these events are historical. The bulk of Nicki and Isabel’s book is taken up with everyday, easily solved issues like Isabel redecorating the girls’ shared room without Nicki’s knowledge. Any attempt to bring history back into focus gets derailed as the sisters disagree over New Year’s goals and resolutions, or the Hoffman parents give a bare nod to their interfaith status without relating it to anything else in the book.

Overall then, the Hoffman sisters, who should’ve been great additions to American Girl, come across as attempts to sell more dolls and let their line poke fun at itself. Nicki and Isabel feed the rampant consumerism American Girl has been excoriated for in recent decades. There is little to no evidence that tacit approval of consumerism was unintentional. Moreover, Isabel and Nicki’s story is so packed, yet so light on plot, that it’s difficult to say what real-life girls are meant to learn from them.

If the answer is, basic lessons about getting along with siblings or accepting a non-traditional family, those lessons have already been covered many times over–more than 15, to be precise. If the answer is, lessons about helping the common good, that has been an overarching AG theme from the franchise’s outset. With Isabel and Nicki, the gravitas American Girl once had appears lost. At best, its last vestiges are disappearing in the face of more dolls, more outfits and accessories, and more token books.

Contemporary “History”: Hurting More than Helping

If gravitas is disappearing from American Girl’s historical line, it might seem like the answer is, “Make the line more relevant and contemporary.” Uniting the historical with the contemporary often works, across many mediums. For instance, American Girl’s spiritual successor Dear America worked for older girls because it united American history with the contemporary concept of a secret diary. And in fact, American Girl has had some success with its contemporary incarnations. The original Just Like You dolls, first introduced circa 1995, were a huge hit when they debuted. The Truly Me and Create Your Own dolls that have followed more recently, as well as online incarnations like avatars from InnerStar University, also found a broad audience. And when American Girl introduced their Girl of the Year line, both creators and fans were hopeful that modern American girls would feel like a real “part of history” because for the first time, characters with fully fleshed out stories were living in their worlds. Modern girls would no longer have to rely on lookalike dolls whose personalities and stories they could imagine, but never see “brought to life.”

However, recent developments suggest AG’s contemporary lines, especially Girl of the Year (GOTY) and World by Us (WBU) are hurting the brand’s image and gravitas, not helping it. The choices made for these lines are not telling girls, “You’re a part of history, too,” as the Just Like You tagline put it. Instead, GOTY and WBU are telling modern girls, history doesn’t matter. They are making history from scratch. While the idea of girls and women making history is great in itself, the way AG presents it has plenty of holes. Those holes have made the contemporary lines, and American Girl as a whole, look stale, repetitive, and out of touch.

Adventure Replaced With First-World Problems

The first problem with AG’s contemporary lines is, they seek to make contemporary girls a part of history. Yet, no real “history” exists, and thus, no coming-of-age opportunities exist. As journalist Alexandra Petri wrote in her opinion column for Oregon Live, “Sure, maybe you picked your first American Girl because she resembled you–but the whole idea was to give girls an entry point to history. [In the] important times past, there were girls who were Almost, But Not Quite Like You.” Petri goes on to write, “People…use [dolls, action figures, and stuffed animals] to navigate miniature worlds. Limiting the canonical adventures to the present-day, first-world problems of Little Girls Who are Just Like You is a mistake.”

This might seem harsh and arbitrary. After all, Petri is an adult who doesn’t play with American Girl dolls or read their books the way a target audience member would. But the further Petri goes into her thesis, the more justifiable her argument is. She hones in on past heroines like Kirsten and Addy, writing, “Kirsten was adventure itself. At one point in her story, someone dies of cholera…she has to tangle with winter and rough conditions.” Petri describes Addy and Momma’s journey North from slavery as “terrifying,” but focuses on how they “hold to their dream that…one day, their family will be together in freedom.”