An Overview of Anime in the Mecha Body of Japan’s Economy

Within five minutes of turning on my hotel television in Tokyo I had seen two commercials for water bottles sold by One Piece characters and a McDonalds anime-style ad for jobs.

Anime’s seamless integration throughout Japan extends from the sprawling hub of Tokyo’s anime district Akihabara, to the anime packaged food at the local conbini in Tokushima. While the commercialization of anime reflects both Marvel and Disney in the western market – from branded alphagetti to t-shirts.

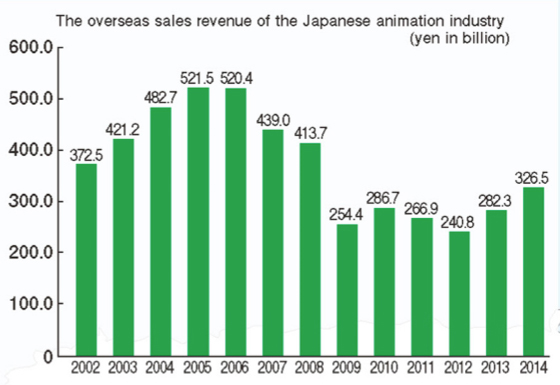

It is undeniable that anime’s influence has helped to shape the foreign market through overseas distribution. Also due to its integration it has followed the rollercoaster rise and fall of the domestic market. This mimicry is thanks mainly to anime’s historical and current existence as a cornerstone of Japanese media. Thanks to this interconnectivity the future of anime in the Japanese economy even against in the face of rising competition through internet distribution is cautiously optimistic.

Anime’s Place Historically and Beyond

While Japan itself began producing silent animation in 1917 through cutout animation techniques imported from France and the United States, televised anime did not begin until 1963. Osamu Tezuka created Tetsuwan Atom (or Astro Boy in English) in 1963 and it became the nation’s first weekly TV anime series. At the infancy of animation broadcasting only seven animated programs, including Tetsuwan Atom, were broadcasted.

Originally anime was quite stilted and used fewer frames due to terribly low funds. Tezuka’s company was forced to offset the losses and low income with copyright income. The Atom character was placed on chocolates by confectionary maker Meiji Seika, which began the deep and long-held connection between merchandising, the Japanese economy, and anime.

It was not until Studio Ghibli founder Hayao Miyazaki began to create the smooth, high-budget animated movies that anime was truly put on the global map as a contender for awards and on par with American animation. In particular, Studio Ghibli’s Spirited Away raked in a worldwide total domestic revenue of $289 million, with North American earnings of $10 million and a further $29 million from other foreign countries. It also received the prestigious academy award for best animated feature film.

Since the original seven broadcasted animations, anime has grown exponentially. In 2014 alone 322 animes were broadcasted of which 232 were new. This shattered the record of 279 animes in 2006. There is no doubt that anime has grown since its inception and that with it so has its influence on the Japanese economy. What remains to be seen is its place in the future of Japan’s economy.

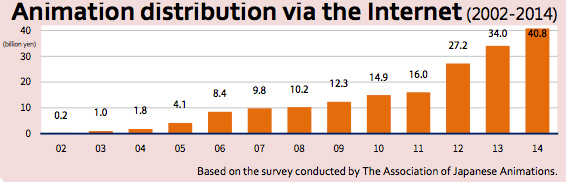

Historically Japan’s domestic anime market had three sectors: feature length films, TV shows, and DVDs. With the recent shift in media distribution to more internet based services like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon, televised anime must compete in order to survive. Some of the previous market sectors will soon cease to exist, something that is occurring not only in anime in Japan, but globally. In fact, in 2014 the animation distribution market through the Internet was $40.8 billion yen, a 20% increase from the previous years, rivalling that of the theatrical animation market.

Anime has thankfully begun to shift towards internet distribution, with upcoming Netflix original animes like Perfect Bones and Blame! on the horizon and the popular Crunchyroll streaming service.

Anime Consumption and the Economy

Just as digitalization has begun to shape how people access anime and how distribution channel filter anime, anime has often followed the general Japanese economic trends. This connection shows a direct correlation between anime consumption and the economy.

Proving this correlation are the following facts: (1) In 2006 – well before the worldwide 2008 market crash – anime consumption hit its peak; (2) in that same year – with the exclusion of panchinko machines and “other revenue” – anime had a domestic revenue of 194.7 billion yen; and, (3) during the recession, consumption hit its lowest at 129.5 yen (again with the exclusion of panchinko and other revenue).

One reason for this mimicry is consumer buying patterns during good and bad economic times. When Japan’s economy does well, anime consumption has followed suit as people have disposable income to spend on figures and DVDs. Similarly, as the economy continues to struggle to recapture the glory of pre-economic crash – with the accompanying slump in advertising and birthrates in Japan – anime also faces both a weaker market and increased competition from rival entertainment forms such as video games and cell phones.

To combat both increased entertainment-dollar competition and stagnant overseas markets, a $500 million fund, “Cool Japan,” promotes cultural items abroad hoping to mimick South Korea’s successful entertainment industry-investment, putting the lucrative kpop on the global entertainment map. The “Cool Japan” fund has resulted in anime localization projects, pop culture exporting, and the Anime Consortium Japan—a media company streamlining anime distribution.

During the economic recovery of 2009, Japanese prime minister, Taro Aso, said, “Japanese content, such as anime and video games, and fashion draw attention from consumers around the world.” Knowing the economic strength of anime, Japan hoped to use it at that time to stimulate its post-crash economy.

And anime consumption has increased – in spite of increased competition from digital media – helping to bolster Japan’s economy. That Japan’s leaders recognize the strong tie between anime and the economy is a hopeful sign for anime, increasing Japan’s investment in anime as a media export even in the face of a poor economy and competition from other forms of Japanese “cultural media.”

Japan’s faith in anime’s marketability is justified by the multiple smash hits generating huge amounts of domestic and foreign revenue. While Japan’s economic health often seems to dictate the sales of anime and its related products, often anime stimulates and feeds Japan’s economy.

In 2014 a 9.5% growth in anime sales (655.2 billion yen) from the previous year seems largely due to Yo-Kai Watch, a children’s supernatural anime debuting January 2014. The show was an instant smash hit, leading to extensive cross-platform marketing of products, games, manga, and more.

In its profitability, Yo-Kai Watch is not rare, Tetsuwan Atom‘s success and Attack on Titan‘s consequent media empire being similar. Attack on Titan generated $60.5 million in manga, DVDs, Blu-ray discs, CDs and novels, not including other merchandise. It even generated an astronomical sales jump – for the first time in 18 years – of 107.3% for Japanese publisher Kodansha.

Attack on Titan was a breath of fresh air from the more “pandering” animes – created after the recession due likely to economic instability. These animes, including harem and idol animes, were usually geared towards otaku fans typically doing well by catering to an established and devoted fan base.

With its success, Attack on Titan helped revitalize the anime industry and, due to its popularity both domestically and overseas, attracted new anime fans. Because of its increased revenue, anime has continued to be an imposing force in Japan’s economy.

Integrating Anime into Consumerism

Anime seems unique due to its seamlessness and common integration it is marketed into daily life in Japan. Everyday items – such as noodles, soda pop, and soap – are often branded with instantly recognizable anime characters.

While in the West sponsored-products and -merchandise exist, it is less prevalent than in Japan. In Japan the economic reach of anime extends past anime television shows and anime merchandise – such as figures and wearable goods – and into every commercial area of society.

Perhaps this is because animes are, by nature, meant to be assimilated into various parts of society. The theme songs for most anime shows are not created specifically for the shows, as are many familiar tunes in the West. Often songs by an already a popular band these are chosen, simultaneously promoting both band and tv show. Likewise, anime voice actors are stars in Japan because of their anime work, unlike the voice actors of western cartoons, selected because of their already-existing star power.

Usually quite blatant product placement is commonplace as well. Pizza Hut appears in Code Geass is like an omnipresent god, and Tiger and Bunny took it a step farther, having real companies sponsor their “sponsored superheroes.” Anime’s symbiotic relationship with product placement is an integration of real world media into anime and, in return, placement in real world media.

Akihabara, Tokyo’s anime center, shows the prevalence of anime branding. Akihabara expands streets with endless merchandise stores, anime panchinko machines, anime-themed sex toys (a tie-in mostly exclusive to anime media that Marvel or Disney will likely not recreate in New York or Los Angeles), and anime CD stores.

With such a large presence in the everyday life of Japanese people – from food to music to TV – it is understandable that anime’s powerful reach and economic power in Japan.

Anime At a Crossroad

Overall, it is clear that regardless of extent, there is a strong relationship between the economy and anime of Japan. While anime has been affected by Japan’s current and past economic cycles, it has also added significantly to the Japanese economy.

Perhaps most fascinating is anime’s current position: Japan supporting anime in its quest to become an economic superpower while anime simultaneously competes against ever-expanding competition. If anime can find its niche in the changing world cultural industry, perhaps it can claim much of the predicted 40% surge in the cultural industry by 2020.

Because of its proven resilience, even if other forms of entertainment claim some anime revenue, it seems highly unlikely that anime will ever be greatly diminished from Japan’s economy. Anime is so thoroughly integrated into Japan’s culture that removing it would be akin to removing armour from a giant mecha robot – inconceivable.

Works Cited

Ferreira, Mike. “What Attack on Titan’s Sales Mean For the Anime Market – Anime Herald.” Anime Herald. N.p., 08 Oct. 2013. Web. 09 Aug. 2016.

“Japan Animation Industry Trends.” Japan Economic Monthly (2005): n. pag. Japan Economic Monthly. JETRO, June 2015. Web. 9 Aug. 2016.

“Kodansha’s 1st Sales Jump in 18 Years Credited to Attack on Titan.” Anime News Network. N.p., 23 Feb. 2014. Web. 08 Aug. 2016.

Masuda, Hiromichi, Ryusuke Hikawa, Tadashi Sudo, Kazuo Rikukawa, and Yuji Mori. Report on Japanese Animation Industry 2015. Ed. Hiromichi Masuda and Masahiro Hasegawa. The Association of Japanese Animations. N.p., Jan. 2016. Web. 9 Aug. 2016.

Melrose, Kevin. “$60.5 Million in Sales, ‘Attack on Titan’ Is Its Own Media Empire.” Comic Book Resources. N.p., 30 Dec. 2015. Web. 9 Aug. 2016.

Nagata, Kazuaki. “‘Anime’ Makes Japan Superpower | The Japan Times.” Japan Times. N.p., 7 Sept. 2010. Web. 08 Aug. 2016.

Reuters, Elaine Lies. “Why Japan Is Counting on Anime, Manga to Boost Economy.” ABS CBN News. ABS-CBN Corporation, 22 July 2013. Web. 9 Aug. 2016.

Yasuo, Yamaguchi. “The Evolution of the Japanese Anime Industry.” Nippon.com. Nippon Communications Foundation, 20 Dec. 2013. Web. 9 Aug. 2016.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Japanese animators have been aggressively selling their products overseas.

Citation needed.

No money in Anime anymore. These companies use old distribution methods. They need to short circuit the fan-sub pirating by getting episodes out soon after they air in Japan. Anime distributors in the US have been dropping like flies over the last 5 years and that’s not helping out the creative side of the equation.

It is amazing how important time-to-market has become.

I had hoped to get a job writing anime, but so far I’ve had no luck. None of the companies seem to have any openings. Not that their websites make it easy to even find that out. It seems they only want Japanese writers. Which is a shame because I have three projects which as far as I can tell are all unique, and quite mature.

Back in the mid-90s when I first got into anime, I really enjoyed OAV/OVA series because they were short, and usually began and ended within about six or seven episodes or so, and some of the shorter TV series that only ran for maybe one or two seasons (so about 26 to 52 episodes give or take). But a lot of the most popular anime now is just too long, and has been running for a decade or more. Way too long for my tastes. Especially since most of the shows that are targeted towards the shonen demographic (pre-teen to mid-teen boys) use the same basic formula.

I love Japanese anime.

Stuff like Naruto and Bleach are great – they’re the easily digestible anime that anyone can get into. It’s a staple that the industry needs. There needs to be a certain penetration of the child market in order to foster that enthusiasm as the kids grow up. Otherwise they’ll give it all away as the world bears down on them.

Why does all japan anime have a cute furry talking sidekick. Or a sidekick that is really annoying? And when they talk it’s annoying and N-O-T cute.

Comics can be a tool for serious expression in long stories.

Right now the Anime Industry outside Japan is growing, but shrinking within Japan. But I guess the definition for Anime needs to be clarified. In Japan Anime refers to anything animated, so it also covers Batman, etc cartoons.

Anime is great because it had vision. The idea of space colonies was invented in Mobile Suit Gundam back in 1979, and it inspired a generation with ideas of colonising other planets.

The robot suits we’re just seeing becoming a reality were also first thought up in Anime.

I think that’s what’s missing in modern anime, the vision.

Japanese’s cartoons are going back in time. 1980’s was cool but now things changed. Voltron and Robotech was the best series from japan anything else is sub par.

Many Japanese probably are not aware just how popular anime is outside of Japan.

Thanks for writing about my favorite art form, anime.

Anime like art is a reflection of it’s time and audience. Anime in the 80s was heavily influenced by American pop-culture such as Star Wars, Star Trek, and American films, because much of the Japanese youths were really into American stuff.

Nowadays, it’s more uniquely Japanese. Anime is more geared toward adults(otaku) who watch it as an escape. Shows paint a more exciting picture of life that is prettier than the hard work-loaded, Japanese adult world. This is why most westerners who got into anime a decade ago are turned off by the new stuff- it lost it’s western appeal. So anime in the west is certainly on the decline, but anime in the east is still remarkably going strong.

Interesting article. I stopped watching a lot of anime a long time ago. Too much of the “moe” genre. Though you would never know that these guys weren’t making money, what with all the expensive merchandise they sell on the side.

Anime is great. Getting fans into the product by offering a quality product that makes them happy and want to share with pals is the best thing.

I think a lot of the charm has been lost as anime caters to the horny otaku set rather than trying to appeal to broader audiences. A lot of the characters are characters we’ve seen before a million times and the plots are highly unoriginal.

The perspective of this article was cool. “Kids” anime when I was younger seemed to only reach western audiences if there was an associated product to sell. Not just Pokemon which had the Game Boy games and the figures to push, but Yu-Gi-Oh, Beyblades, B-Daman, and Bakugan which seemed to only exist to make mundane toys and activities action-packed and cool. It’s curious to see that contrasted with real world product placement and branding in the anime that we don’t see as much of.

I loved reading this article and think it’s great.

I get a lot of insight and earn more admiration for anime the more I learn of its history. The evolution of the medium is unique and still developing as new seasons roll out so there’s a constant metamorphosis within the genre. Though, a constant critique that I encounter with both veteran and new coming anime fans is an overwhelmingly negative view on the “moe” genre. Many argue that Lucky Star started the moe trend, and it’s starting to be present with every coming season. New Game! was the moe of last season, and it generated lots of fan praise and equal amount of disdain from others who distance themselves from the genre. In general, I believe moe is here to stay considering the fact that Love Live!, Yuru Yuri, and Kiniro Mosaic are beloved spectacles that have been sweeping up the hearts of many. Although the genre is beginning to create a sort of divide amongst anime lovers, I hope moe can gain a respectable name alongside action or psychological as many of the series generated from the genre are nothing less than brilliant and uplifting. While moe may be contrived or boring to some, the eccentric style is constantly hilarious, adorable, and wonderful at developing well-liked characters. It is incredibly different from the other genres associated with anime, but that only makes it all the more interesting.

I just don’t understand how anyone can seriously discuss anime and not mention “Akira”, its monstrous influence, as well as “Cowboy BeBop”. These two were game changers, and both are for adults without the fan service so many folks seem self-righteously indignant about. Both are amazing works of art that had a profound and lasting influence.

Anime itself has changed an entire entertainment genre and will continue to do so. We have seen so many American cartoons adapt anime art styles!

Anime is an amazing marvel that has really added to the entertainment industry. While comics and cartoons have greatly improved since the 60s the fact remains that anime was and has been more advanced than what the U.S. has produced, so much so that Japan can use them for ads.

I really enjoy anime, and found this article fascinating. Thank you!

This is pretty interesting. I had no idea anime was such an influence in Japan’s evonomy and I never thought about the similarities between Disney and Anime. I could see it when compared to comic books because of the comic to tv show adaptation. I wonder what could happen if Anime sees a larger spike in live action or video game adaptations.

This is a very interesting topic. I’m currently writing a history research paper about technology in Japan and it seems I’m the first in the world to debate about what type of technology affected Japan the most. Thank you for this article.