Antietam: Literature Adds to America’s Bloodiest Day

The Battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862), is the day that is known as the bloodiest day in American history, when more Americans died, were wounded, or went missing than any other (almost 23,000). The battle is seen as a turning point in the Civil War (1861-1865), not because the tide of battle turned in favor of one side or the other, but because what the Civil War was fought about changed. Soon after this battle ended, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation: Ending slavery became the goal of winning the Civil War.

C.X. Moreau, in the Promise of Glory: A Novel of Antietam 1 and Richard Croker, To Make Men Free: A Novel of the Battle of Antietam 2 provide contrasting, and, at times, overlapping perspectives on this battle.

Five days after this battle, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. In part this executive order read:

That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom. 3

Even though slavery is seen as the cause of the Civil War, ending it was not initially Lincoln’s goal: The goal was to bring states that had seceded back into the Union. Lincoln had considered issuing this proclamation well before Antietam, and Northern newspapers had speculated on him doing so beginning in the summer of 1862, but he felt he needed a military victory to issue this order.

In the fall of 1861, Lincoln pushed to end slavery in Delaware. Delaware was a state where according to the 1860 census there were only 1,798 slaves, significantly different from Georgia with 462,198 slaves. Lincoln’s proposal was for a gradual end to slavery in Delaware with slave owners compensated by the federal government. The Delaware legislature rejected this proposal and stated they opposed any effort, “to place the negro on a footing of equality with the white man.” 4

To Make Men Free, has numerous references to the expected Northern reaction to Lincoln issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. If a border state, like Delaware, with few slaves, strongly rejected Lincoln’s gradual approach to free slaves, his Emancipation Proclamation could set off riots in the North. John Hay, Lincoln’s private secretary glanced at the Emancipation Proclamation in Lincoln’s drawer and thought:

There will be hell to pay when that weapon is fired. Only God will know what will happen. Insurrection. Rape. Murder. …White men rioting in the North and a black rampage throughout the South. Slaves demanding to take up arms for the Union. 5

Literature can bring a dimension to the battle which cannot always be understood from the usual historical sources. How two novels about the Battle of Antietam look at it provide insight and raise issues that complement the historical study of this day in American history.

Historical fiction has a long history and the “turf wars” between historians and novelists indicates a continuous struggle over who owns history? Novelist, Kate Grenville published The Secret River in 2005. A year later she claimed her novel was “historiography.” 6 This novel focused on Australia and the taking away of Aboriginal land. Historians argued with what they saw as her taking liberty with what was known and stretching the truth significantly. One historian critical of Grenville’s book wrote, “We cannot post ourselves back in time. People really did think differently [in the past]. …Are we seduced into an illusion of understanding through the accident of a shared language?” 7 Both novels addressed here, in fact, put the reader in the minds of soldiers and statesmen more than 150 years ago. In that sense, historical fiction can address history in a way that a historian will not dare to go and taking liberty with what is known is part of the work of a novelist.

Captain Blood (1935 starring Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Basil Rathbone) is based on a novel published by Rafael Sabatini in 1922. 8 One historical account about the real Peter Blood who was convicted of treason, sold as a slave, and then escaped to become a pirate stated, “this Peter Blood [in the novel] bears little resemblance to the [historical figure].” 9 Historical figures may, in fact, differ, yet can overlap, in how historians and novelists present them. Eric Foner, a historian who won the Pulitzer Prize for History, made the work of historians sound as though they share much in common with novelists who write historical fiction. Foner stated, “Works of history are first and foremost acts of the imagination.” 10

Historical fiction has a place alongside how historians approach the study of history—not necessarily on a lower level. Elevating historical fiction to a higher status helps in understanding the limitations of what historians can do, such as getting into the minds of figures during moments from the past. One writer stated, “[Historical fiction writers can make] clarity of chaos, not to hand us answers but to capture the way history shapes, wounds and implicates us.” 11

A battle, with all its moving parts, addressing the political goals that can override military objectives, the relationship of commanders to political leaders, the combat situation of numerous military units at different locations and times scattered around a battlefield, can become a narrative in the hands of a historical fiction writer, which a historian may not be able to achieve. Conversations, intense ones at that, had to have taken place during a battle, and wondering what those conversations must have been like, is an understandable issue to consider. Wondering what those conversations involved and their intensity, may reveal the limitations of historians but in the writing of an historical fiction novelist, conversations can become feasible and credible and help to open up how to better understand a battle: History can support literature and literature can enhance history.

Neither novel is a WHAT IF about the Civil War (such novels exist) rather as Croker stated in To Make Men Free:

I researched this topic for three years before I even set a word to paper and I assure you that I have done my best to maintain a high level of historical accuracy. 12

Historical fiction, as one writer defines it is, “the intersection and blurring of fact and fiction.” 13 The term for this genre of books, may be an incorrect phrase to use but has become popularized. The two novels addressed here might also be considered as part of historical interpretation. Historians have long argued about what matters and why, how certain events came about, and why the outcome was as it was. Both novels, in some ways, fall within the range of issues historians address. In that sense, both novels complement historical studies that cannot easily convey the intensity, emotion, confusion, despair, and regret that are all present as life and death hang in the balance. One writer of this genre of books stated, “Historical novels don’t just tell us what happened; they makes us feel. They create empathy for what other people went through in different times.” 14 Another writer stated, “Reading history allows us to understand what happened. Reading historical fiction allows us to be moved by what happened. Even after we know the facts, we continue to search for sense and meaning.” 15 Antietam, the enormous casualty toll that one day produced, still draws us to examine what happened and why, 159 years after the battle ended.

Where to Begin a Battle?

Both novels unfold before September 17th, the day of the battle, but start at different points. Battles are an outgrowth of what came before. Battles are not mutually exclusive from each other but connect in a myriad of ways: Generals learn from previous engagements what to change and what to apply again, soldiers transform from raw recruits to seasoned veterans, artillery crews learn to improve their accuracy, a President learns how to replace generals looking for one who will fight to win.

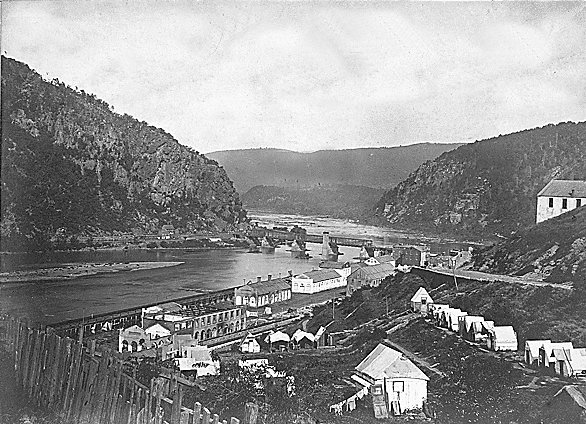

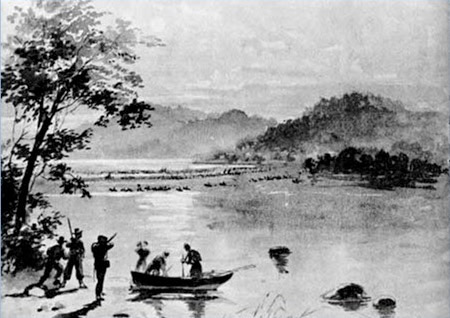

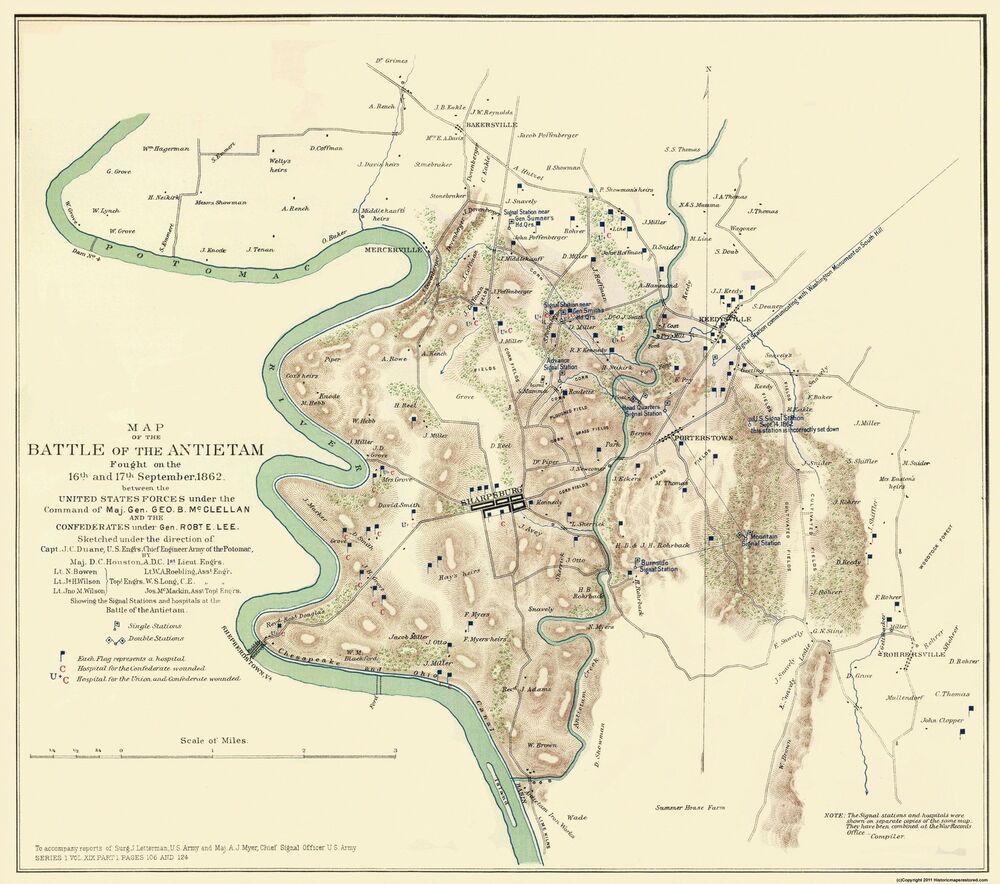

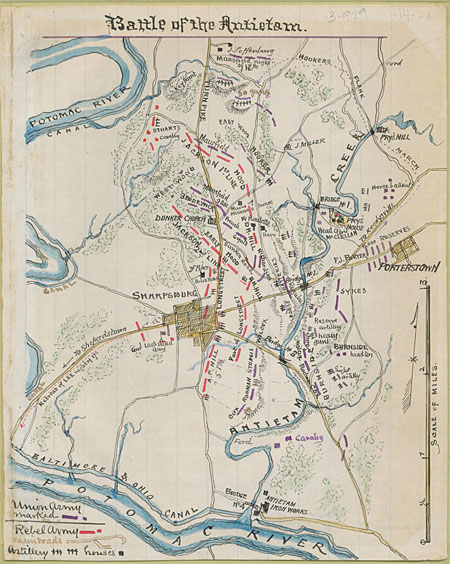

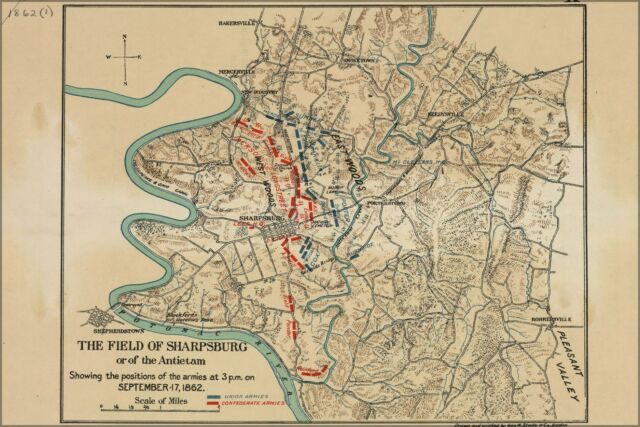

In the case of Promise of Glory, the Confederate attack on Harpers Ferry, a Union depot and armory, located in West Virginia (which only became a state in 1861 and was admitted into the Union in 1863), is where the Battle of Antietam begins. By car, Harpers Ferry and Antietam, or rather Sharpsburg, the Maryland town near Antietam Creek, are only twenty minutes apart, but seventeen miles of marching can seem like a lifetime.

Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, in Promise of Glory states his reason why Harpers Ferry needed to be captured as he planned to head north into Maryland. Lee states, “The garrison at Harpers Ferry must be reduced. I cannot leave it on my line of communications.” 16 Adding to Lee’s comment, Major General James Longstreet, one of Lee’s two corps commanders (the other being Major General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson) states:

The guns and other supplies will be useful, and if you’re bound on movin’ beyond Maryland, we’ll have to run ‘em out of there.

…We’re a long way from home already. 17

To Make Men Free also focuses on Harpers Ferry, much in a similar way. Both novels address Jackson’s preparation to lay siege to the Union defenses, which will fall easily but took precious time, time that was taken away from joining forces with Lee’s main body as they headed toward Maryland. Some 21,000 Confederate troops were needed to assault the Union garrison and to secure the almost 13,000 Union soldiers when they surrendered. Lee’s total army consisted of only 40,000 troops (possibly 55,000 if stragglers are included, which are addressed as an issue in both novels) slightly more than half the number of Union troops which would confront him at Antietam.

Longstreet in Promise of Glory, says that “Harpers Ferry is just a sideshow,” and added:

Lee is after [the Union] army. He wants to draw them away from Washington, being ‘em to battle in the open far enough away from the capital that he can run ‘em to ground after it’s over, finish it with one big battle up here. 18

Harpers Ferry may have been a sideshow, but it played a significant role in what unfolded at Antietam. Moreau writes:

Lee had been forced to turn from his main line of march and engage the garrison at Harpers Ferry in order to secure his lines of supply and communication with Richmond. In order to do so, he had divided his army into smaller commands and surrounded the arsenal. Even now his army was divided, separated by mountains and rivers. 19

As fighting at Antietam developed, Lee’s depleted force that was still divided and would only be joined together late on the day of battle, can only hope for a standstill. Longstreet’s insight into Lee that he wanted “one big battle up here” to bring the war to an end, would not happen.

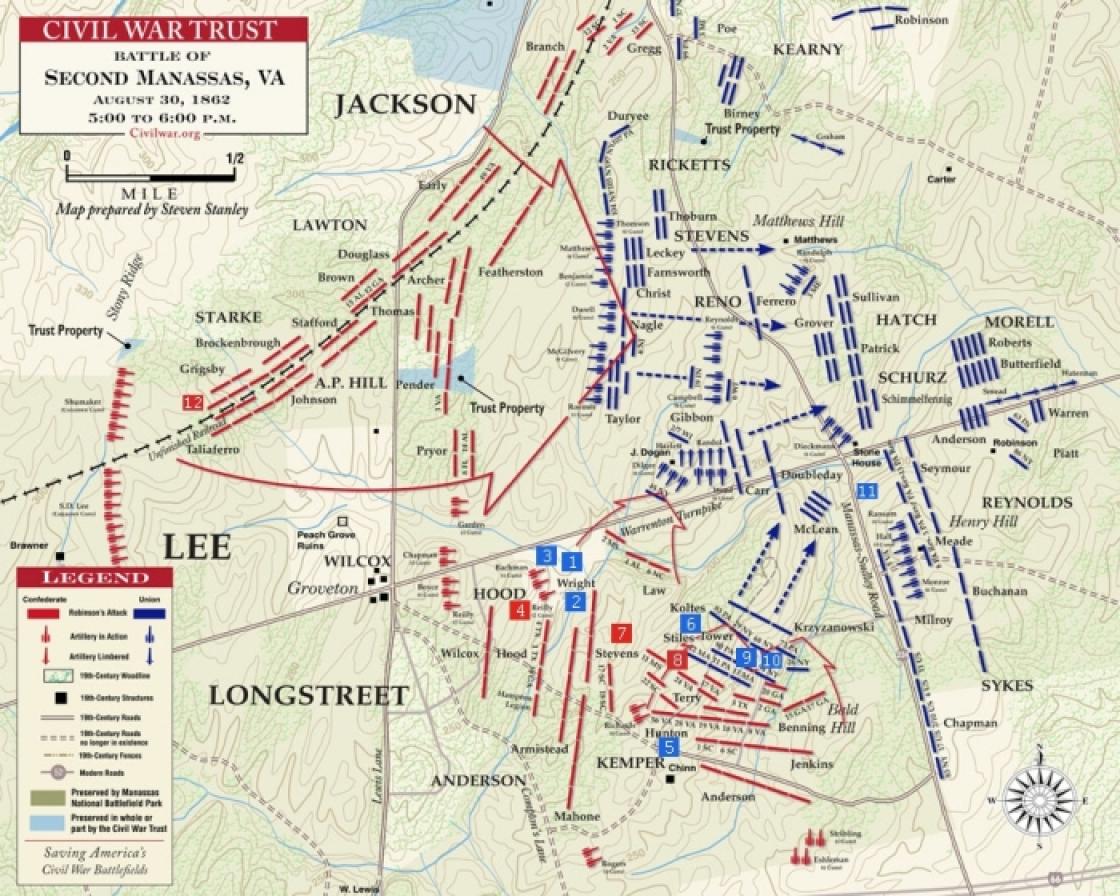

To Make Men Free, however, begins with the Battle of Second Manassas (August 29-30, 1862). The Confederate bombardment of Harpers Ferry took place on September 14th and 15th, Second Manassas was three weeks earlier. The two novels together provide an interesting contrast in the fourteen hours of fighting that will take place at Antietam.

Second Manassas made Robert E. Lee a hero in the South, three months after taking command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee replaced General Joseph Johnston after he was wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines on June 1st. To Make Men Free states:

For the first time in a year Virginia was virtually free of Yankees. With the invasion repulsed, Lee was a national hero, and the people of the land were anxious to know him. 20

Second Manassas, pitted Lee and the Army of North Virginia against Major General John Pope and the Army of Virginia. Pope was convinced he had Jackson’s corps effectively defeated, which was one of the two corps making up Lee’s army. He believed one more assault and the Confederates would surrender. In To Make Men Free, Pope ignored reports that reinforcements came to Jackson’s defense, Longstreet’s corps. One exchange between Pope and an officer goes:

Officer: General Pope, sir. General Reynolds begs to report, sir, what I have recently seen for myself that a fresh Rebel force, many thousands in number, sir, has pulled along the Rebel right flank.

Pope: You are simply, excited, young man. Those flags you see are Porter’s men and I’m glad to hear of it.

Officer: Begging your pardon, sir, and with respect, But I’ve been there myself, and I am certain that this is an entire Rebel corps.

Pope: I’m sure you are, my boy. 21

Pope launched an assault and was met by Longstreet’s troops who inflicted heavy casualties, particular with effective artillery bombardment.

Major General George McClellan, who led Union troops at Antietam was not at this battle but played a significant role in the battle’s outcome, which is one of the reasons why To Make Men Free set the stage for Antietam by beginning with Second Manassas. Second Manassas, by focusing on it in To Make Men Free, was foreboding in that the casualty count was just over 22,000 total for both sides, which contrasts significantly with the casualty count of just under 5,000 for First Manassas (often called Bull Run) a little over a year before Second Manassas.

McClellan had been conducting a campaign aimed at assaulting Richmond, the Confederate capital. But, in late August 1862 he ended that assault which allowed Lee to shift forces to fight Pope. Pope would need reinforcements from McClellan to oppose Lee’s army, but McClellan was slow to reinforce Pope, although McClellan said that was not true. 22 Yet, in correspondence with his wife he indicates that things would go poorly for Pope writing, “…Pope will be badly thrashed within ten days and [Washington] will be very glad to turn over the redemption of their affairs to me.” 23 In other words, he was well aware of what Pope was going to face and indicated no urgency to assist him.

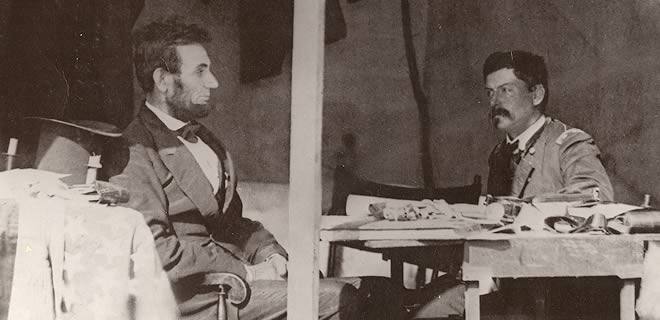

In To Make Men Free, Lincoln in a conversation with someone at the White House states that McClellan’s inaction would mean disaster for Pope:

Pope is in trouble. How much trouble no one knows. Pope himself probably doesn’t know. But mark my words…McClellan knows. He knows whole well. …I am afraid…that Mr. McClellan is…playing a different game. 24

With McClellan no longer a threat to invade Richmond and Pope’s defeat at Second Manassas, Lee was free to consider advancing north into Maryland which led to the confrontation with McClellan at Antietam. Lee’s victory at Second Manassas set the stage for a battle that would have taken place somewhere in Union territory, it just happened to be Antietam. In addition, the personality of McClellan with his faults which was highlighted with Second Manassas, will matter at Antietam.

Two novels that, taken together, provide perspective on how to look at the battle that unfolded around Antietam Creek: Events before September 17, 1862 mattered to what developed on that day.

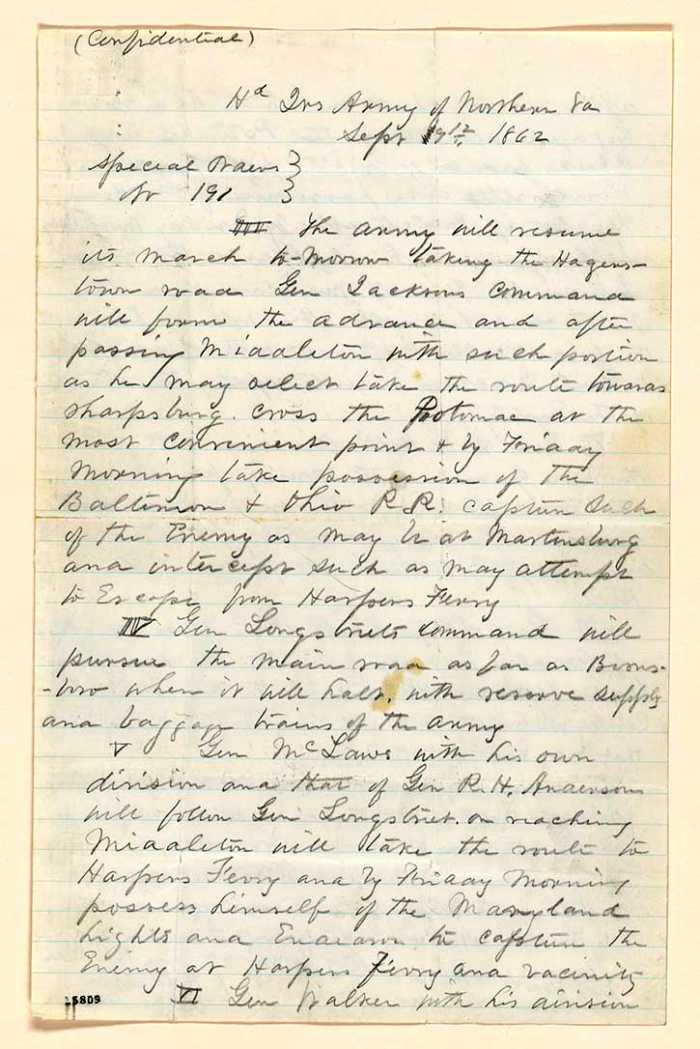

Those Wrapped Cigars and the Lost Opportunity of Knowing Lee’s Orders

Two Union soldiers resting under a tree come across cigars wrapped around paper. Opening the paper, they read, “Headquarters, Army of Northern Virginia, Special Orders No. 191.” The soldier opening the paper, as expressed in Promise of Glory, “felt a surge of excitement t as he skimmed down the page, read the names of Rebel generals he had heard countless times about in newspapers.” 25

Both novels address Special Orders No. 191. The papers are quickly sent up the chain of command and reach McClellan. A member of his staff verifies that the orders are genuine, based on recognizing the signature of the officer who signed the orders: Here were Lee’s plans regarding dividing up of his army as they proceeded into Maryland. five days before the Battle of Antietam, and they were laid bare before McClellan. To Make Men Free describes the orders as, “[spelling] out in detail each and every movement of each and every [Confederate] division.” 26 In To Make Men Free, McClellan remarks on the importance of having this information, “This document is worth five corps to me.” 27 In the Promise of Glory, McClelland reflects upon what he now believed were Lee’s plans:

Lee had no intention of invading Washington. Nor did he mean to engage the Union army In Maryland. The papers in his hands made that plain. Lee intended to invade the North, drive into Pennsylvania, all the way to the Susquehanna River. Capture Harrisburg. Perhaps Philadelphia. 28

The Special Orders revealed that Lee has divided his command with Jackson, Longstreet, as well as other generals, sending divisions in different directions. Lee moved quickly at Second Manassas since he feared McClellan and his army meeting up with Pope and presenting a formidable challenge if he had to fight both Union armies combined, but McClellan did not think the same way days before Antietam: The opportunity to attack Lee’s army in pieces is lost. In To Make Men Free, Brigadier General John Gibbon (later to rise to the rank of Major General) reflected on McClellan’s reaction to reading Lee’s orders:

Why [are we waiting to act] tomorrow? If the dispatch is that damned revealing, why not today? It was yet noon and a “good hard day’s marching” could yet be done between now and darkness. 29

Neither novel develops the WHAT IF aspects of this lost opportunity, but the chances are that if McClellan had seized the opportunity to attack Lee’s army in pieces, the casualty toll from America’s bloodiest day might have been avoided. In addition, it is difficult to speculate about where the war might have stood after such action. Could the Civil War have ended in 1862, instead of continuing until 1865? Certainly, the greatest WHAT IF of the Civil War arose when a soldier opens cigars wrapped around a piece of paper days before America’s bloodiest day. Wars are about lost opportunities and McClellan had his brass ring within his grasp and did not grasp it. Another general might have acted differently. Lincoln in To Make Men Free, as news reached him of Lee’s march north, commented on McClellan:

George is purely a defensive commander. He lacks the will to go on the offensive. We are informed that the enemy is on the move again, this time into Maryland, and I need-the nation needs-a commander to lead our armies against [Lee]. …I fear that General McClellan is not that man. 30

McClellan’s reaction or rather inaction after reading Lee’s orders, will be reflected in how the battle unfolded on September 17th and how he approached the aftermath of the battle. Lost opportunities were presented to McClellan, the Special Orders, the way he conducted the battle, the way he approached the day after the battle, all added up to prospects that were not mined. A well known quote goes, “Opportunities are like chances, you wait too long you miss them. ” 31 In Promise of Glory, Moreau reflected on Lincoln and what he saw coming:

A battle was a terrible, delicate thing. A matter of timing and balance that forgave no general his mistakes. A matter of acting with confidence, precision. And there, in the gathering light of dawn, with ten thousand men marching toward the enemy at his command [Lincoln] knew that George McClellan would fail him. 32

Why was Napoleon successful in battle? One reason was that he took advantage of what is known as coup d’oeil. Roughly translated from the French it means “stroke” or “eye,” or, as one writer put it “glance.” 33 Napoleon took advantage of the moment, he saw the opportunity and, for him, success came with acting: McClellan was completely devoid of this insight.

Lee learned that McClellan had a copy of his orders. The orders were discussed openly with a Confederate sympathizer present who got word of the discovery to Lee’s command. Lee used the word “providence” that he was facing McClellan, knowing that any other Union general would have acted upon them. Croker reflects on Lee’s thinking:

McClellan has the largest army ever assembled and the most important piece of military intelligence ever handed to a commander, and still he waited. 34

A Battle without a Battle Plan

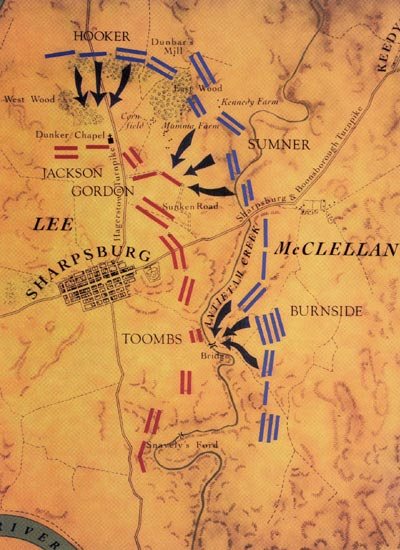

At 5:00 A.M. on the September 17th, Union Major General Joseph Hooker gave orders to his commanders. To Make Men Free reports Hooker’s words:

It falls on us, gentlemen, to initiate this battle. Our orders are vague, but I believe we have General McClellan’s permission to attack. And attack we must. We’ve already spent two days watching the enemy improve his positions and I’ll be damned if I’ll sit around and watched another. 35

Notice, the words that Hooker uses, “our orders are vague.” An historical account of the battle stated, regarding McClelland’s battle plan that, basically, there was no plan. As that account stated:

Antietam was the first and only battle George McClellan ever planned and personally directed. He neither issued a battle plan to his lieutenants nor called them into council to explain his intentions; he commanded that day entirely by circumstance. 36

Hooker’s corps was positioned on the right flank of McClellan’s army. As they advanced through what is known as the Cornfield, Confederate Major General Jeb Stuart with his cavalry positioned on Nicodemus Hill on Lee’s left flank spotted the Union advance: The battle was joined.

The clash of armies was not limited to infantry but included artillery. To Make Men Free states:

The biggest guns on the field, the twenty-pound Parrotts, joined the fight with deadly accuracy from a distance of almost two miles, and in an instant the air above the corn filled with smoke, fire and iron and with arms, legs, and heads of Rebel pickets tossed thirty feet into the sky. 37

Lee, upon hearing artillery, remarked, “Today will be artillery hell.” 38

As Union infantry pushed forward, the inevitable resistance kicked in with Jackson’s corps receiving assistance to push back. Hooker’s assault on the position held by Jackson’s corps was answered and Union troops were pushed back. Within the first hour of fighting, 2,000 men were dead, approximately 61 per cent of the day’s casualties were in the morning. Hooker later recalled the intensity of the fighting:

[E]very stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the [corn]field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they stood in their ranks a few moments before. It was my fortune to witness a more bloody, dismal battlefield. 39

Lee, although outnumbered in troops, had an advantage with interior lines that allowed him to shift forces to where they where needed quickly. Hooker had hoped, or expected, that as he conducted his assault, Major General Ambrose Burnside would have begun his assault in the vicinity of Rohrbach’s Bridge (which would after the battle be renamed Burnside Bridge) far to the left of his position. If Burnside had attacked and succeeded in advancing on Confederate positions, it would have made it difficult, if not impossible for Lee to shift forces to counter Hooker’s assault. As the morning phase of the fighting wore on Moreau indicated how Hooker felt:

[Hooker] silently cursed Burnside and McClellan and all the other bumbling fools at army headquarters who couldn’t coordinate an attack, who couldn’t move men or regiments or armies. It could go all terribly wrong. If they waited much longer, his boys would be in and the Rebels would throw their reserves at them, and it would be more than he could handle. 40

At one point Hooker saw that the Confederates were retreating, some due to infantry success, some to the effect of artillery bombardment. As Hooker’s troops advanced Moreau states how Hooker felt as he lost confidence that Burnside had successfully launched his attack:

A sudden sickening thought came [over Hooker], that Burnside had bundled it, that he hadn’t gotten his assault off and that no attack was coming, and that he had walked his men into a trap. 41

Some two hours after fighting had commenced, Hooker knew he heard no guns fired from the general vicinity of Burnside’s position, so knew he was not assaulting and simply responded, “damn him!” Moreau described the scene that Hooker was seeing, “Lee and Jackson were exhausted, their men licking their wounds in the trees beyond the church.” 42 Hooker reflected on where the battle stood at that moment and Moreau expressed Hooker’s thoughts:

Now was the time. If only McClellan or Burnside or someone would have the sense to hit them on the other side of the field. A division-size assault would suffice. Anything to distract them…prevent Lee from shifting men toward this end of the field. 43

Hooker took out his frustration on McClellan, and thought to himself, “Damn, McClellan and his never-ending caution. Good men will die because he is too timid to commit the army.” 44 Lee understood Hooker’s thinking and said to himself, “If General McClellan coordinates his attacks on both ends of the field, the situation will become impossible to maintain.” 45

Moreau’s assessment of McClellan as a general is not kind:

The army had groomed McClellan to be a general since the day he had left [West Point]. And now here he was, with the largest army any officer had ever seen at his disposal, and he was too timid to fight it the way it was meant to be fought. He had all the trappings of a general except one. He lacked the instinct to drive the enemy with everything you had and destroy him.

George McClellan would never understand that. Nor would he ever understand that winning battles involved fighting, sometimes to the very last of your strength. 46

Moreau raised the issue of mutiny—that Union officers would band together to remove McClellan from command. Hooker, although wounded and removed from the battlefield is approached regarding this issue and responded, “We shall speak no more on this subject, Mr. Smalley. I shall not take the field again today. My wound prevents me, and my officers must know this.” 47

George Smalley was the chief war correspondent for the New York Tribune. It was some three decades after the Civil War ended that Smalley wrote about the attempt to remove McClellan from command–a major event that was never revealed until years after the war ended. Croker also raised the mutiny issue and cites a conversation between Smalley and a Major James Wilson, who served on McClellan’s staff during the Maryland Campaign. Wilson would later rise to the rank of Major General. The conversation goes:

Wilson: Several of us believe, sir, that this battle is being badly fought. We have the opportunity to crush the rebellion, right here and now. But McClellan is…afraid, sir. He is scared to death that Lee is going to attack him. He is so afraid of losing that he will not give us a chance to win.

Smalley: Why are you telling me this, Major? Frankly, it sounds like mutiny.

Wilson: I know that as well as you do! We all know that! But we also know it is the only way to crush Lee and end the rebellion and save the country. I am a soldier, sir. These other members of the staff who agree with me are general officers and even corps commanders. Any effort on any of our parts to encourage, or insinuate, that General McClellan should be relieved of his command would be regarded, as you say, mutiny. [Y]ou are a friend of General Hooker’s. 48

As far as Burnside and what he was doing, some two hours after the battle had begun, Croker stated, “He sat in his camp and listened to the battle and waited for his former friend, George McClellan to tell him when to attack.” 49 At approximately 10:00 A.M., Burnside got orders to advance on Confederate positions. 50 If there were plans for a coordinated attack on Confederate positions, it was difficult to understand when that was supposed to happen.

It was apparent that Union officers besides Hooker and some on his staff were not the only ones expecting a coordinated attack. Major General Israel Richardson was angry about his division being held in reserve and then well after the battle was underway finally entered the fight. He was also angry that McClellan had failed to orchestrate a coordinated attack. 51

Reading both books present a picture of two writers who complement each other regarding the course of the day’s battle. Neither writer has a high opinion of McClellan. Regarding Lee, he is seen primarily as fortunate to have had McClellan as his opponent, much as he was fortunate to have Pope as his opponent as Second Manassas: Lee out-generaled both Pope and McClelland.

George Smalley had a low opinion of McClellan as well, which comes across in both books. At one point as the day wore on, McClellan tells Smalley, “I have no infantry.” Smalley in To Make Men Free thought to himself:

[I] remembered the tens of thousands of men held in the rear. [I] remembered the lines of cold fully equipped and unused guns parked wheel-to-wheel on the other side of the creek. [I] remembered Major Wilson’s words, “This battle is only half finished…but McClellan will do no more.” 52

Just as McClelland failed to act after getting Lee’s Special Orders, he failed to take advantage of opportunities that were presented to him as the battle unfolded. Out-generaled is a good expression that reflected the importance of having the right commanders in place at the right time: McClelland was not that general.

What two novels do well is to give readers a good understanding of military leadership under battle conditions. Historical studies alone cannot always convey the emotions that help to understand leaders under fire. Battles are intense and lives hang in the balance–that might be an understatement but readers wanting to understand battles, in this case Civil War battles, can get a sense of the intensity that confronts soldiers and their leaders as they look death in the face through novels such as the two addressed here.

Both novels give a sense of the tremendous fear and anxiety soldiers faced. Moreau wrote:

–Every man hopes, and prays, and longs for his own survival in that one instant [when you face enemy volleys]; knows the savage fear that comes from the realization that death is speeding toward him; and that it is blind, and unjust, and uncaring. 53

Jewell Parker Rhodes, a writer whose works include Douglass’ Women, which won the American Book Award, wrote:

I love historical fiction because there’s literal truth, and there’s emotional truth, and what the fiction writer tries to create is that emotional truth. 54

For all the blood that coated the battlefield, at the end of the day, neither side could really claim victory in any decisive sense of the word.

The Day After

There was talk of more fighting to come the next day, but that did not happen. Lee had his back to the Potomac River. Before the fighting began even McClellan thought of Lee crossing the Potomac and the position of his troops if battle resulted around Sharpsburg. In Moreau’s book, McClellan turned to one of his officers and commented:

How can that be? Offering battle with a river at their backs? They would have no line of retreat. It is unthinkable. General Lee would not risk such a battle. 55

Yet McClellan did not see Lee’s back to the Potomac as an opportunity for him when Lee did what McCllelan thought would never happen. The terrain favored McClellan, the land slopes down toward the river. 56 After the capture of Burnside Bridge, Union troops were on high ground early on the afternoon of September 17th, Confederate forces needed to retreat in the direction of Sharpsburg and in the direction of the Potomac River. As the afternoon wore on, more Union troops crossed Antietam Creek over Burnside Bridge, pushing Confederate forces further back toward Sharpsburg and the Potomac. While the day’s fighting had been anchored around Antietam Creek, by the late afternoon, the line of fight was away from the creek and closer to Sharpsburg and closer to the Potomac River.

The terrain had favored Lee during the fighting on September 17th, he was on higher ground and could see the movement of McClellan’s forces. This allowed him to effectively use his interior lines and shift forces where they were needed. As one study of the terrain at Antietam stated, “[T]he Confederate forces were deployed in defensive positions with interior lines on higher ground with a better view of the battlefield than their enemy.” 57 The position of the armies did not favor Lee on September 18th.

As Burnside’s forces readied for a final assault to cross the bridge and take the heights that Confederate forces held, the issue of what awaited them on the other side of the creek arose: The use of Union cavalry suddenly came up. Burnside in Promise of Glory, turns to a member of McClellan’s staff and asked:

Did the commanding general’s staff think about that? Perhaps our cavalry could have scouted the Confederate position; then maybe I would know what to expect beyond the Antietam or where the fords lie. 58

This was another indication of the lack of coordination that permeated McClellan’s war planning. Union cavalry was concentrated in the center of the Union line. An officer later wrote:

It is one of the surprising features of this surprising battle that the Federal cavalry, instead of bring posted, according to the practice of the centuries, on the flanks of the infantry, was used throughout the day in support of batteries, in rear of the Federal center, and in a position from which it could have been impossible for it to have been used. 59

After success, crossing the bridge and scaling the heights on the over side of the creek, what came next? As the day’s fighting came to a halt, that question hung over the evening. Longstreet in To Make Men Free, summarized for Lee where he and his forces stood after fourteen hours of fighting:

Our artillery is a shambles and low on ammunition. Some damn Yankee cavalry regiment captured a third of my reserve artillery ammunition before it ever got here. …They have almost as many men in reserve, General, as we have total! 60

There was an additional issue that Longstreet brought up with Lee, “[Add] to the Antietam casualties the] two thousand more casualties lost at South Mountain.” 61 South Mountain has not been addressed (and for the sake of keeping this essay a reasonable length) is only tackled quite briefly. South Mountain, located, more or less, halfway between Harpers Ferry and Sharpsburg, was the location of fighting three days before Antietam (September 14th). South Mountain consisted of three separate battles to gain control of the passes, which were needed for Lee’s forces to pass through heading toward Sharpsburg. Approximately 50,000 forces fought around this mountain with casualties totaling around 5,000.

Taking what Longstreet said to Lee regarding the circumstances facing Lee’s army at the end of fighting on September 17th, together with the casualties from South Mountain, Lee’s response to Longstreet sounded like pride overcoming pragmatism. In Croker’s book, Lee stated, “I will not be driven from the field by George McClellan. We cannot allow him to claim a total victory over us.” 62

As the morning of September 18th came upon the battlefield, McClellan was urged to renew his assault. Eventually, McClellan, as his temperament has shown, came down on the side of caution and expressed his caution to a general urging him to fight. In To Make Men Free, McClellan states, “It’s another of Bobby Lee’s traps, sir. No one knows that better than me.” 63 McClellan might have felt he knew Lee, but he should have been thinking along of lines of Longstreet’s thinking about where his forces stood in comparison to Lee’s, and that did not happen.

Major General Henry Halleck, General-in-Chief of all Union armies, 70 miles away in Washington, was waiting to hear of battle developments: McClellan had sent a telegram at 1:45 P.M. on the day of battle that simple read, “We are in the midst of the most terrible battle of the war-perhaps of history.” 64 Nothing more was heard from McClellan. But, on the morning of September 18th George Smalley went to the telegraph station in Frederick, Maryland and sent out a detailed account of the battle. Unknown to him, the telegraph operator sent the telegram to the War Department in Washington where it was read by Halleck. Washington then forwarded the telegram to Smalley’s office in New York City. After reading George Smalley’s account of the battle, Halleck discussed the situation with Lincoln. George Smalley is a significant character in the drama that unfolded around Antietam Creek and is raised frequently in To Make Men Free. Halleck stated to Lincoln:

According to that newspaperman, Lee was trapped with the [Potomac River] to his back and was there for the killing, and I will wager a dollar to a dime that [McClellan] is no more ‘in pursuit’ than a sheep pursues a wolf. 65

Confederate forces began to make their way back across the Potomac River after a day without fighting. 66 Lee reflected on what McClellan would do as his forces crossed back across the Potomac. In Promise of Glory, Lee states:

You know George McClellan won’t pursue us through Virginia. He thinks his army can’t march more than a few miles a day. If we get on the road tonight we can put enough distance between ourselves and them so that they’ll have a two-day march to catch up. 67

While Moreau focused on the low opinion Lee had of McClellan, Croker in To Make Men Free, addressed Smalley and how he felt that McClelland’s actions at Antietam were nothing short of disastrous. In early October, several weeks after Antietam, Smalley picked up a copy of Harper’s Weekly which had headlines such as “McClellan to the rescue,” and “Burnside holds the hill.” Smalley thought to himself, “If these poor people-these oblivious people—only knew. If they could see for themselves.” 68 The Northern public during the Civil War period, began to agree slowly with Smalley’s opinion of McClellan by the spring of 1863 (although the Democrats would pick McClelland as their Presidential candidate for the 1864 election in which McClellan would win only two states, one his home state of New Jersey). The public also blamed Halleck, which deflected some attention away from McClelland. Emil Schalk, published Campaigns of 1862 and 1863, Illustrating the Principles of Strategy. Schalk was an emigrant from Europe, and wrote several books which became popular and were widely read and which made military affairs accessible to the general reader. Schalk presented a copy of one of his books to Lincoln. Schalk in Campaigns was highly critical of McClelland. 69 While Smalley was an observer of Antietam, Schalk far removed from the battle, could come to much the same conclusion about McClellan’s capability as a general.

The Emancipation Proclamation and its Impact

Lee brought his army north to hopefully gain a victory that would have led to Great Britain and France recognizing the Confederacy. Both novels about Antietam address this issue in very few sentences, collectively no more than two paragraphs. Furthermore, what is addressed here regarding the impact of the Emancipation Proclamation, does not come from either novel since neither one developed in any way what this proclamation meant to the course of the Civil War. By briefly addressing Lincoln’s proclamation, however, it helps readers to understand why Antietam is a significant turning point in the Civil War. One historian wrote:

[What was] accomplished by the Battle of Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation was to explode the illusions and hope of compromise that had hitherto limited the violence and social disruption of the conflict, and push the Civil War past the point of no return. 70

McClellan was opposed to the proclamation and felt it would “dissolve our present armies” since white Union soldiers would oppose it and that would lead to dissent which would weaken the capability of Union armies to fight. 71 Since the North won the Civil War, McClellan’s fear did not happen.

Was the proclamation the reason that neither Great Britain or France recognized the Confederacy? On this one historian wrote, “The prevalence of antislavery sentiment among various elements of the British and French public played a minor role in government decision making.” 72 Another historian wrote, “A Massive pro-Union reaction occurred in Europe-especially in Britain.” 73 Two historians in disagreement about the impact of Lincoln’s proclamation on Great Britain and France and where they stood regarding the Civil War.

While historians may disagree over the impact of the proclamation on European affairs, the impact of the battle and the Emancipation Proclamation can be seen as significant in two ways. First, the removal of McClellan was needed to pursue a more aggressive form of warfare against the South. A historian addressed McClellan’s attitude toward the war:

McClellan…did not really want to crush the rebellion. …[He] had made little secret of his dislike for abolitionists. …[He] wanted to restore the Union [in a way] that would preserve slavery and the political power of [the South]. 74

The second way to see the impact of this battle and the Emancipation Proclamation is the significant increase in African-American soldiers joining the Union war effort. Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War, felt that Lincoln needed a military victory in order to issue the proclamation, just issuing it would not do: A victory at Antietam made the proclamation a reality.

Prior to Antietam, a few thousand African-American soldiers joined the Union army, within a year of the proclamation going into effect beginning in January 1863, more than 100,000 African-Americans joined the Union army. By the end of the war, some 10 per cent of the Union army was composed of African-American soldiers. Lincoln in addressing the presence of black soldiers on the battlefield made an exaggerated statement in March 1863, “the bare sight of fifty thousand armed and drilled black soldiers upon the banks of the Mississippi would end the rebellion at once.” 75 That did not happen, the war continued until April 1865, but the impact of Black troops cannot be underestimated considering that many joined as the recruitment of white troops declined.

A Victory but a Questionable One

The battle was a draw but in terms of the Pope’s defeat at Second Manassas, it was a Union win—all things are relative. Antietam was looked at in relation to Second Manassas. Lee’s invasion of the North was halted, but he came North again to fight at Gettysburg. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation soon after Antietam padded the image of a Union victory. An Antietam park ranger put the battle’s outcome in the context of what Union forces had gone through in 1862:

The Union forces had suffered three catastrophic defeats in 1862. They have been humiliated by General Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley, mauled by Lee in the Seven Days Battle and again at [Second Manassas]. They huddle around Washington, D.C. in a state of very low morale. 76

McClellan had a moment of glory, but it did not last. Lincoln waited until the day after the Congressional elections in November 1862 to remove him from command and replaced him with Burnside.

Together, both books present a picture of McClelland which borders on incredulous. Lee is certainly addressed in both books, but the point is that since Antietam presented an opportunity for McClelland to crush Lee’s army which would have led to speculation about how long the Civil War would have lasted after a significant victory, then the focus on McClelland in understandable.

Works Cited

- C.X. Moreau, Promise of Glory: A Novel of Antietam, New York, A Forge Book, 2006 ↩

- Richard Croker, To Make Men Free: A Novel of the Battle of Antietam, New York, HarperTorch, 2004 ↩

- Transcript of the Proclamation | National Archives ↩

- James McPherson, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief, New York, Penguin Books, 2008, p. 87 ↩

- Croker, p. 36 ↩

- Historians and novelists fight turf wars – let’s flip the narrative (theconversation.com) ↩

- Making a fiction of history… (theage.com.au) ↩

- ebook, Captain Blood by Rafael Sabatini</ (fiction.us), the full novel is here. ↩

- Pirates & Privateers – Captain Blood: The History behind the Novel (cindyvallar.com) ↩

- How Historical Fiction Went Highbrow – The Atlantic ↩

- Why Are We Living in a Golden Age of Historical Fiction? (ampproject.org) ↩

- Croker, p. 463 ↩

- Why We Read Historical Fiction | Gramercy Books (gramercybooksbexley.com) ↩

- Historical Fiction is More Important Than Ever: 10 Writers Weigh In ‹ Literary Hub (lithub.com) ↩

- Why We Read Historical Fiction | Gramercy Books (gramercybooksbexley.com) ↩

- Moreau, p. 33 ↩

- Moreau, p. 34 ↩

- Moreau, p. 42 ↩

- Moreau, p. 68 ↩

- Croker, p. 90 ↩

- Croker, p. 68 ↩

- Leave Pope to get out of his scrape : McClellan’s dispatches : McClellan, George Brinton, 1826-1885 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive ↩

- Elias Nason, McClellan’s Own Story: the war for the union, the soldiers who fought it, the civilians who directed it, and his relations to them., chapter 27 (tufts.edu), in section titled “Midnight.” ↩

- Croker, p. 58 ↩

- Moreau, p. 65 ↩

- Croker, p. 149 ↩

- Croker, p. 170 ↩

- Moreau, p. 68 ↩

- Croker, p. 170 ↩

- Croker, p. 125 ↩

- 13 Quotes to Motivate You to Seize Opportunities (success.com) ↩

- Moreau, p. 192 ↩

- William Duggan, Napoleon’s Glance: The Secret of Strategy, New York, Nation Books, 2002, p. 4 ↩

- Croker, p. 235 ↩

- Croker, p. 240 ↩

- ‘The Roar and Rattle’: McClellan’s Missed Opportunities at Antietam (historynet.com) ↩

- Croker, p. 242 ↩

- Croker, p. 244 ↩

- For Want of a Leader: Lessons on Mission Command from McClellan’s Failures at Antietam – Modern War Institute (usma.edu) ↩

- Moreau, p. 192 ↩

- Moreau, p. 198 ↩

- Moreau, p. 225 ↩

- Moreau, p. 227 ↩

- Moreau, p. 228 ↩

- Moreau, p. 240 ↩

- Moreau, p. 252 ↩

- Moreau, p. 257 ↩

- Croker, p. 334 ↩

- Croker, p. 265 ↩

- Croker, p. 283 ↩

- Croker, p. 302 ↩

- Croker, p. 342 ↩

- Moreau, p. 267 ↩

- Jewell Parker Rhodes – I love historical fiction because… (brainyquote.com) ↩

- Moreau, p. 159 ↩

- Withering Heights: The Battlefield Geography of Antietam — Neil S. Oatsvall, Ph.D. (neiloatsvall.com), the 13th picture shows the wheel of a cannon in the right corner of the picture. Looking to the left shows where the Confederate positions were located after Burnside Bridge was captured. The picture shows the land sloping down in the direction of the Potomac River. ↩

- Harold Winters, Gerald Galloway, William Reynolds & David Rhyne, Battling the Elements: Weather and Terrain in the Conduct of War, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, p. 125 ↩

- Moreau, p. 307 ↩

- Was McClellan’s Cavalry Deployment at Antietam Doctrinally Sound? | Antietam Battlefield Guides (antietamguides.com) ↩

- Croker, p. 349 ↩

- Croker, p. 348 ↩

- Croker, p. 349 ↩

- Croker, p. 356 ↩

- George Smalley’s Vivid Account of the Battle of Antietam (historynet.com) ↩

- Croker, p. 366 ↩

- Union General George B. McClellan lets Confederates retreat from Antietam – HISTORY, a good summary of September 18th. ↩

- Moreau, pp. 349-350 ↩

- Croker, p. 419 ↩

- Carol Reardon, with a Sword in one hand & Jomini in the other: The Problem of Military Thought in the Civil War North, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2012, pp. 32-38 ↩

- Richard Slotkin, The Long Road to Antietam: How the Civil War Became a Revolution, New York, W.W. Norton & Company, 2012, p. 414 ↩

- Slotkin, p. 380 ↩

- Slotkin, p. 409 ↩

- McPherson, p. 160 ↩

- James McPherson, Tried by War: Abraham Lincoln as Commander in Chief, New York, Penguin Books, 2009, p. 71 ↩

- Donald Stoker, The Grand Design: Strategy and the U.S. Civil War, New York, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 227 ↩

- washingtonpost.com: ‘And the Slain Lay in Rows’ ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

When people say the Civil War was about state’s rights, I ask ” What did these states want the right to do?”

When people say the Civil War was caused by the North’s overbearing political power, I ask ” What institution allowed all southern states to inflate their presence in congress, thereby denying just representation to the rest of the country?”

When people say the Civil War was about economics and culture, I ask “On what fundamental institution did the south’s feudal patriarchy rest, freezing their economy and society in amber while the rest of the country grew larger, more diverse, more educated, more connected, and wealthier?”

There are many strands to the tension that led to the Civil War, but they were all united by one central issue. It begins with an s…

Well, I hope you enjoyed by article. Certainly, it gives the idea that the Emancipation Proclamation was a risky thing to do, which makes Lincoln look even bigger in historical perspective.

I hate when some of my fellow Americans claim that this war was not about slavery. Lets take a look at the three most popular alternatives:

1) Economics. The North was overcoming the South (which many people do not know was the 4th largest economy in the world at the time, hardly the backwards territories that many think) economicially and therefore the South had to fight for its survival. Hmm, what was the Southern economy based off of? Cotton and similiar slave based labor.

2) Rights. The North was infringing upon the rights of the South and therefore, similiar to the economics theory, the South had to fight for its god given American freedom. Hmm, what “rights” were the North infringing upon? Oh yes, the right of one’s property, in this case people, aka slavery.

3) Territory: The North was choking the Southern way of life and expansion by stopping the spread of Southern culture. What was this culture and what was the north trying to legislatively block from expansion. OH YEA, SLAVERY.

The American Civil War was about slavery. Any way people want to spin it, it was about slavery. Don’t try to glorify your ancestors and sense of history by claiming something that isn’t true. And for the record – my lineage includes folks that were Georgia gentry whom owned slaves, so please do not dismiss me as some northerner who doesn’t understand the southern way of life.

Yes, it was about slavery. The issue of slavery can be seen as a humanitarian issue, but, certainly, an economic one. By the North freeing slaves, they took a resource away from the South. Think in terms of slaves doing work which freed up Southern whites to fight. I addressed some of this briefly my article on Gettysburg for The Artifice.

I suppose we’ll see a few ignorant pipsqueaks pop up to say that the war wasn’t about slavery, blah, blah, blah. Would it be too much to expect such people to study the subject first before foisting on their deeply superficial and ignorant opinions upon us?

The issue there is less about seeing the Civil War as history and more about the war as still part of contemporary affairs. There is a publishing house that has a whole series of books (I’ve read only one of them) and these books are, sort of, on the Civil War, but really come across as a way, or an odd way, of looking at current America. In my Gettysburg essay I briefly address the Civil War as part of current affairs, not just an historical topic.

Lincoln remains a fascinating character, and I have wanted to read a biography of him for a while now, and am now spurred on to do so by reading this.

How far would a figure like Lincoln make it today in the Republic party? Something is wrong with US society and our political system.

Lincoln would probably not make it that far in today’s Republican Party. My guess is neither would Ronald Reagan. Thank you for reading my essay and it is nice to hear it peaked your interest to want to read more about Lincoln.

Very interesting piece — informative and nicely written.

Thanks for enjoying my article. I’m working on several more essays on the Civil War, it just takes time to try to be (somewhat) original and make sure accuracy is always addressed.

Some historians have forgotten about the Lincoln Douglas debates before he became an elected official of any kind. Lincoln was antislavery before he became president and some people including blacks are pondering his motives for the emancipation proclamation after he became president. The truth is the south succeeded from the union as soon as he got elected president because of his views on slavery. After the start of the civil war to save the union he might as well go all in to save the union and end slavery once and for all.

If any of the Lincoln haters havent realized yet, the USA has never lost a war and wouldn’t have lost the civil war the. I live here and as backwards as the south still is are you kidding me. I understand the true Lincoln, and he used every political trick to accomplish his pre presidential goal to end slavery and the civil war was a two for one deal he couldn’t pass up Bravo Mr President…..Bravo.

Lincoln’s anti-slavery position evolved over time. Where he was when he issued the Emancipation Proclamation was not where he was earlier in his political career. At one point he seemed to favor using boats-back-to-Africa as a means to address and end slavery. I don’t think I’ll be getting around to any essay specially addressing Lincoln, but any that do should discuss how he evolved on slavery, not just where he was in those days after Antietam.

“the USA has never lost a war”

Ahem,

Arguably the War of 1812,

Taiwan Expedition of 1867,

Vietnam,

Somalia,

Most likely Afghanistan.

Eh? Don’t get me wrong, although I’m a Brit I have lived in the States and actually fought with you guys in GW1, was thinking of contributing my own thoughts on racism, but thought best leave it to the natives. But seriously, never lost a war? WTF do you call the helos lifting off from Saigon rooftops in 1975?

When you fight a civil war clear through to the end, half your country no-shit loses it. And half the US lost in 1865 in about as bad a way as wars can be lost. Great, gaping swaths of it looked far more like Berlin in 1945 than anything they’d been four years previously.

That loss defined the south (which, unlike the north, didn’t have the option of “moving on” as we now say) for about a hundred years. They’d been right to claim that their former prosperity had been grounded on slavery; no matter how rough blacks had it for decades thereafter, no matter how much “forty acres and a mule” resembled slavery itself in many ways, the south couldn’t just rebuild its former infrastructure, as most defeated countries do. It took decades to reconstruct (possibly a pregnant word) a crude parody of slave society that restored the former ruling families to a bitter parody of their grandeur — and then the north came along again and took even that away. And all the time they’d been losing out to northern industry, decade after decade…

Anybody who thinks all that is behind us just isn’t paying attention. But, at last, it’s no longer primarily a racial matter, and even though it’s still very much a regional matter, it isn’t all that much associated in people’s minds with the events of 1861.

It still can be a racial matter. Evanston, Illinois recently passed a reparations bill. This seems to focus on African-Americans who can show they were harmed by zoning or housing discrimination within the city but, I suspect, it will be used to motivate some places to talk about reparations related to slavery. So, Civil War issues will not be just be historical but remain contemporary.

I suspect Overstreet was probably being facetious.

Slavery was the cause of the war in two different ways, one in the north and the other in the south. The north’s intolerable act of aggression against the south was the election of Lincoln, and that was far, far more about stopping the spread of slavery to new states than abolishing it where it existed. And that in turn was mostly a popular economic argument: just as Joe the individual farmer can’t compete with a guy who owns slaves, so states that depend on free labor will be undersold by those who don’t, especially if the slave states gain a permanent political advantage in Congress.

It may be difficult to separate the economics from the emotional and social positions regarding slavery. Today, years removed from the Civil War, it seems possible to separate economic issues out from others, I’m not sure that was possible at the time. Notice, in my essay I address Lincoln’s proposal to Delaware and how the state legislators responded–well there is economics and social issues all intermingled.

The Emmancipation Proclamation really was that rare moment, a political figure grasping the moment. Few before or since have grasped a nettle in quite the way Lincoln did, in a way that enabled both the Union and those who’d been held as slaves to move forward.

How to look at its impact in the period immediate after it was issued and how we look back on it from the present, I think are different. After all, in looking at the Emancipation Proclamation as just itself is one thing, but then the Civil War ends, Reconstruction happens, then the South slides backwards with the rise of Jim Crow laws and years of fighting–an uphill battle begin to get back to something approaching Civil Rights for African-Americans. With us able to see what comes after the Emancipation Proclamation, we see it in a different way, then it was seen it the time it was announced and when it went into effect in 1863.

Ironic to think that the party of Lincoln – the Republican party – is today the party of those who look back to the Confederacy and its plantations with nostalgia.

Realize that for almost a hundred years after the Civil War, white Southerners did not vote Republican because Lincoln was the first Republican president and ended slavery. Interesting to see Georgia state legislators essentially annoyed Trump lost the state in 2020 (fairly, not because of fraud) so they want to do all they can to make sure they don’t lose again. How to do that? Not by trying to reach out to more voters– diverse voters, but by seeing how they can limit and restrict voting and, as a means to not having to make any changes to their political and public policy positions. Not addressed in anything I’ve been reading is the likely court cases that will come if Georgia Republicans, and Republicans in states such as Arizona pass some of these restrictive voting laws. If, Republicans wanted to only address voting fraud, they could push to issue voter IDs to everyone–think about bookmobiles and how they travel a state. Well, use something like that to issue voter IDs. That’s a first step. Voting by mail is not necessarily simple if, as I needed, my signature verified by a notary. So Republican arguments regarding that are simply to restrict Democratic voters. Unlike, after Republicans lost in 2012, where the idea was how to reach out to more voters, Trump’s legacy after 2020 is not to do that but punish Democratic voters by identifying where they are, how they vote, and how to restrict them.

An angle often not covered in American History about Antietam was that in one way, that is what won the Civil War for the United States, because prior to Lincoln issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, the British dabbled in questioning whether to recognize the Confederacy because of the South’s cotton supply (which they needed for their cloth mills). But the British also had committed themselves to vanquishing slavery as far as they could. The Emancipation Proclamation, in changing the dimensions of the Civil War (that it now was about slavery without question), also cutoff any possibility of British aid (even with trade) to the Confederacy. That plus the British went to the United States’ main competitor for cotton during the Civil War: the Ottoman Empire. Just some food for thought.

Sounds like you have the makings of an article. Just avoid being absolute in your thinking. I think what was going on in Great Britain was more complex. The notion of seeing the Emancipation Proclamation in almost cause and effect terms, avoids the issue of what the British and even the French might have done if Lee was successfully in his Northern operations and the Emancipation Proclamation still existed.

Great piece.

Thanks for enjoying my article. I have one on Gettysburg which also looks at historical fiction on The Artifice. In addition, I’m working on several more regarding the Civil War, probably out over the next year.

I suppose it is a depressing thought that we have passed the anniversary of the assassination of Lincoln, and then the dark years of Andrew Johnson when the sacrifices of the civil war were largely thrown away. That part of the civil war story is less often told (not by Foner of course).

As I mentioned in earlier comment, we can look at the Emancipation Proclamation at the time it was released and even through 1863, but then we can look back from the present and know what happened, particularly as the promise of Reconstruction came to an end and Jim Crow laws came to the South.

Most wars are won by the side with morality on its side, eventually, and with a flimsy cause like Union to fight for, the war may not have been won, but by making it about both Union, but also about the continuing fight for freedom in the US, Lincoln gave the Union a true cause to fight for.

I’m not sure about the morality issue, certainly every side believes they are in the right. It might seem inevitably that the only way for slavery to end was through war.

The attempts to establish a freed slave homeland, makes me wonder what effect it may have had in the formulation of the Balfour Declaration, trying to shoehorn the Jewish Diaspora back into Palestine.

Liberia, in Africa, was established by former slaves. Interestingly, being former slaves did not necessarily lead to them being enlightened regarding how to treat the local population.

For most African-Americans, the Middle Passage and experiences in the New World through slavery are essential to their cultural identity. They are not the same cultural group as today’s West Africans, despite a shared ethnic history. European Jews, for the most part, put their Jewishness and their ties to Palestine at the forefront of their identity. Those that don’t tend to live in Europe or North America. I see your point, but I wouldn’t look to the African-American experience as a precursor to Jewish desire to pray and die in Palestine.

Is it possible to compare African-Americans and slavery and Jews and Palestine? I guess some perspectives can be gained, I’m just not sure what. With that say, maybe there is an essay in there somewhere that can be written to address the issue.

No, there were numerous thinkers who pondered the recreation of an Israel, long before the current issue. Balfour was convinced early on about it. But that was the same time as numerous discussions of moving freed slaves to this or that part of the globe, with West Africa at the forefront.

Liberia had Americans slaves, or rather former slaves arrive there. So a “back-to-Africa” movement was part of the debate about ending slavery.

Lincoln was a Vampire Hunter too, apparently.

OK, I enjoyed the movie.

America needs a new Emancipation–freeing the endangered middle class from corporatism that threatens to undermine democracy, equal opportunity, and that ideal American Dream of having a good life if one plays by the rules and works hard. We need something to reverse more than thirty years of economic stagnation and diminishing standards of living. We need a new Lincoln who is revolutionary enough in his thinking to recognize this problem, and a new Congress made up of honest ethical men who can begin to reverse it.

I’m not always sure how to do this. While the thinking as an aspiration is good, how is brought down to the level of the practical.

I saw a great documentary: Ric Burns, ‘Death and The Civil War’- very good and one historian made an excellent point- the Southerners did not wage war over the mistreatment of their dead but for the preservation of slavery in perpetuity and would not have been any less bitter had the North bent over backward to please them after the war.

I don’t see how the South would have easily, or peacefully, given up slavery. the Ken Burns documentary film is good.

Thanks for enjoying my article. I have one on wrote, which is on The Artifice, about Gettysburg. I’m working on several more regarding other Civil War battles, probably out over the next year.

Some years back I had the rare opportunity to see the penciled first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation in Lincoln’s own hand with numerous corrections at the incomparable Huntington Museum in San Marino, CA. begun in the early 20C by the nephew of one of the Big Four behind the Transcontinental Railroad. I confess I fought back tears reading it- gave me chills.

A very nice thing to say about seeing the document. Probably, when I’m in Washington I can get an opportunity to see it at the National Archives.

I really recommend watching Ken Burns’s The Civil War documentary. Anyone seen it?

I met him once, years ago at the opening of the Negro League Baseball Museum in Kansas City. All of this films are enjoyable.

I just re-watched Burns’ Civil War show on Netflix. My reaction was the same as when it first came out. It is, for the most part, a sentimental piece of fluff, designed to teach the audience a certain mood about the war. Sweet, sad music in the background, a photograph of corpses in a ditch, the camera panning slowly up the daguerotype of a young soldier, poignant words from a letter home. All this is entertaining — and true enough as far as it goes. But it does not go far enough. Vast areas of importance are ignored or mentioned only briefly. For instance, the show tells us that Lincoln feared he would not be re-elected in 1864 — Atlanta fell — and he was re-elected. That’s it. That’s it for an entire presidential campaign in the midst of Civil War. For another instance, Lincoln’s cabinet was filled with very smart, head-strong men like Seward, Chase, Stanton and Wells. What did they do and how did they interact? Barely a word. Large numbers of white people in the South actively opposed secession — even slavery. Their role was. . . what? In the last portion of the show, Burns shows many pictures and even motion pictures of old veterans from North and South marching together in remembrance of this terrible war. It is as though the Civil War led to reconciliation and peace. That may have been 1% true — but the real legacy has been bitter division between regions and, more important, continued, vicious oppression of black people.

Burns had 9 hours to present the Civil War. That is enough time to give a pretty fair picture of what happened and why. But the series came out so-so at best. That’s my opinion, anyway.

I tend to agree with you. In my article on Gettysburg on The Artifice I briefly address Burns. These are enjoyable films, if they stimulate a desire to learn about the Civil War that is good.

I hear you. The music could be really cloying, and there was a general tone of almost religious reverence throughout the whole thing that could be really off-putting. It was also the genesis of the whole Ken Burns documentary aesthetic which has caused so many rolled eyes over the years (Jazz, Baseball, etc): slow camera pans over old photos, sad music in the background, etc. But despite that all, it’s still worth a watch, if only for Shelby Foote, as well as the for the amount of research, both documentary and photographic, which is pretty staggering. He did do another documentary on Lincoln’s Gettysburg address, but perhaps another piece on Lincoln’s life and presidency is in order, to cover the areas missed in The Civil War.

Yes, Burns presents good visuals, which help to get his stories across. These are interesting films that he has made, but there is a need to just stop and think about choices made in putting together his documentaries-what is included and what is left out. In my Gettysburg article I briefly address Burns.

The documentary made me feel like I was there.

The New York Times Magazine (March 21, 2021) has a conversation with Burns. A good piece.

The Ken Burns series goes a long way toward telling us how our ancestors felt.

The New York Times Magazine (March 21, 2021) has an interview with Burns. I see in some places the date says March 20th (but that’s a Saturday), the magazine is in the Sunday editions (so that’s March 21st).

If you are interested in the Civil War, a must read is the ‘Memoirs and Selected Letters’ of Ulysses S. Grant. One of the finest works of non-fiction in American literature.

I’ve often thought of reading Grant’s memoirs (which I read somewhere is considered as America’s first bestseller, I’d have to find out if that is true).

Someone else mentioned Grant. I’m thinking of doing an article on his memoirs, still haven’t figured out how to approach it yet.

It is indeed beautiful prose, and it was written as Grant was dying of throat cancer. Former presidents had no pension in those days, and Grant had lost nearly all of his money in bad investments. He undertook the immense project in order to save his family from poverty, and was encouraged by his friend, Mark Twain. It was an act of raw courage and determination, and he finished it very shortly before his death.

I am serious thinking of doing an article on Grant’s memoirs in the similar way I looked at Gettysburg and Antietam.

The sentimentality might seem a bit much these days, but we live in a cynical age. The Civil War was an emotional and traumatic experience, and was fought in an era of great sentimentality. One of the Civil War characters in a novel by Hervey Allen, speculating about what future generations will think of it all, says that when the war is recounted by historians, they will carefully narrate the events that happened. But what will be entirely forgotten is how people felt.

I’ll need to look into the novel you refer to, I’m not familiar with it.

William Gaddis wrote an unpublished play called “Once at Antietam” which resurfaces as a play written by one of the characters in his later novel “A Frolic of His Own.”

Antietam completists can read the play in his archives at Washington University. It’s more about the aftermath than the battle itself.

The best Civil War battle story is surely Ambrose Bierce’s “Chickamauga.”

I’m familiar with Gaddis, having read some of his works. Regarding what is at Washington University I know a few people there, I’ll see if they can help get me a copy, if that’s possible. Thanks.

Check out the PBS “Liberty! The American Revolution” which teaches you more in six hours than all you ever learned in school. The horrors of our first war were no less barbaric than any of late.

I will, thank you.

Sad to say, slavery wasn’t at the core of The Civil War though it should have been. The war was really fought over the very simple, fundamental question; what is the fundamental nature of this Union? Is it to remain this Jeffersonian/Neo-Catonian pastoral utopia or become a modern industrial economy under Hamiltonian lines.

Well difficult not to address slavery.

People still think the America Civil War was about slavery?

What the war started out about and what it became about changed. As a result slavery became the issue, which might not have been thought so by, say, Union soldiers joining to fight in the early days of the war.

Those of us who have spent the last 25 years studying its history certainly do.

Scholarship on slavery and the Civil War has developed well over, say, the past thirty years. When I first became aware of the Civil War, probably around 1962, in some substantive way, I don’t remember much focus on slavery and the war. It’s good to see this emphasis and how it has begun to effect how people look at the Civil War.

People still think the America Civil War was not about slavery?

There is an entire publishing house with books devoted to the theme that slavery was not the real issue of the Civil War. I read one of their books and have been considering if it’s possible to read a number of their books and read an essay about this alternate reality.

One of the most interesting aspects of this story is the way Lincoln’s attitudes on race changed. He never could abide slavery, but his beliefs about the proper place of black people in America changed dramatically over time. It is, I think, an indication of his greatness. Today we are so obsessed with consistency in our leaders that we see changing, growing, learning as bad things. This is a mistake.

I suspect the war forced his views on slavery to change.

Lincoln’s attitude changed dramatically when he saw black troops dying in large numbers for the Union.

Initially, he was ambivalent to slavery; happy to contain it and “let it die on the vine”. The Lincoln-Douglas debates; which many critics hold up as evidence of virulent racism, were no more than Lincoln having been outmanoeuvred and having to play to the gallery. The idea of relocating slaves to West Africa (in large numbers) was a pipe dream.

Lincoln was a pragmatist (first and last) who’s overwhelming ambition was to save the Union

Regarding the Lincoln-Douglas debates, the actual account of them had to put together from different newspaper sources. Where he would have been regarding a post-slavery America is interesting speculate about since his death was right at that point of the war ending.

Based on today’s population, the Civil War’s now revised 750,000 dead would be 7 million. Tens of thousands of corpses lay unburied at war’s end. My maternal grandfather said as a boy in the early 20C South, he and his pals would search the woods for war relics digging musket and minie balls out of trees, digging up bayonets, buckles and sometimes coming across human remains.

I briefly address Civil War casualty figures in my Gettysburg essay. It is easy to throw a figure (number) out there and it becomes generally acceptable. It is important sometimes to just stop and question those generally accepted numbers and how they were developed.

It’s sad to see how amoral the USA has become since Lincoln.

America would never be able to prevent secession now nor have the Popular Will to abolish slavery. We probably couldn’t even pass another Civil Rights Act like in 1964 because we’ve got so many sleazoids in office now that they wouldn’t lift a finger to uphold the Constitution unless the Corporations told them it was OK.

We’re not physically at war with each other–that might count for something. I always see usually make-believe “patriots” who easily yell about a coming new civil war and wonder what they’re talking about. I’m (somewhat) optimistic and believe that within the oddness and madness, some good comes forth.

The US got onto the freeing the slaves bandwagon pretty damn late.

You’re probably right about that but it is difficult to see how slavery could have ended peacefully years prior to the Civil War.

An excellent article.

Thank you for enjoying my article. I have one addressing historical fiction and the Battle of Gettysburg and I’m working on three more similar articles on other Civil War battles.