When Art House Was King: The Golden Age of International Cinema

As a teacher of English to speakers of other languages, I have encountered a plethora of wildly disparate individuals from across the globe. The one constant I have discovered, whether the student is from Puerto Rico, Saudi Arabia, or France, is that Hollywood cinema reigns supreme. Adults and adolescents from Beijing and Berlin enthuse about the exploits of the Avengers and Batman, and largely ignore the works of Zhang Yimou or Wim Wenders. In the United States, it may seem to be eerily similar; we are a nation of cinema buffs, devouring them at a shrinking number of multiplexes, watching them on Netflix or on our ubiquitous iPhones. The key difference, however, is that many Americans uniformly ignore foreign films. However, in recent years this has started to change; Parasite became the first non-English language film to win Best Picture, and the feat is likely to be repeated as innovative filmmakers across the globe continue to make their works available to an international public.

It remains to be seen if there will be a type of renaissance of world cinema in the 21st Century, but in the years following World War II leading up to the 70s, countries that most Americans had never set foot in were entrancing bohemian pockets of the nation with a seemingly endless stream of innovative, unforgettable works of cinema.

It is true that cities such as Boston, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles were the primary venues for these international films, and of course not a single one of these could match West Side Story in the box office department. Regardless, filmmakers from Italy, France, Japan, Sweden, and India reached an audience of Americans who felt nothing less than a sense of enlightenment. Without this boom, the fabled 70s “New Hollywood” boom of Altman, Coppola, Scorsese, et al is almost inconceivable.

With the relatively recent passing of a key auteur of this fertile period, France´s Jean-Luc Godard, this era seems even more to be a relic of the distant past, as now essentially all of the major icons of this period- Fellini and Truffaut, Bergman and Kurosawa, among many others, have long since passed away.

Here is a remarkably incomplete history of the long-gone days when international art-house cinema reigned supreme.

Early Days

Hollywood’s pervasiveness has always made it easy to believe that American film has always been at the forefront of cinema. This ignores France’s instrumental role in the creation of cinema itself, as well as the fact that the German expressionist classics Metropolis, Nosferatu, and Pandora’s Box were as innovative and influential during the silent era as the more-popular works of Chaplin or D.W. Griffith. The self-congratulatory Academy Awards debuted in 1928, and just as in the present day, foreign cinema was essentially ignored by the short-sighted mass of Hollywood insiders. In 1937, Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion, a rollicking, humanistic WWI epic, became a surprise international sensation, and it was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar; the first nomination for a foreign-language film.

In the years following World War II, the early, tentative rumbles of the art-house boom emerged in Italy. While the end of the war lent a wholesome sweetness to emotional Hollywood classics such as The Best Years of Our Lives and It’s a Wonderful Life, the ravaged European nation faced its ills head-on in the unvarnished, low-budget Rome, Open City (Roberto Rossellini) and Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica). These two films were filmed on the war-torn streets of Rome itself, rebuking the gaudy, polished sets of mainstream cinema. The actors were mostly non-professional, the plots threadbare, and the style documentary-like in their tight focus and uncompromising realism. These two filmmakers found themselves at the head of a movement enshrined as “Italian Neo-Realism.” Shoeshine even won an honorary Oscar for Best Foreign Film, finally giving recognition to the deserving cinematic works made outside of Greater Los Angeles.

It was De Sica’s subsequent film, however, that truly lit the spark, not only for neorealism, but for the imminent art-house explosion in general. After the success of Shoeshine, Hollywood producer extraordinaire David O. Selznick offered to produce De Sica’s next film, The Bicycle Thief, with one condition: Cary Grant would play the lead role. Luckily, De Sica ignored this request, and cast non-actors in the roles of a working-class Roman family. The story: an impoverished father and son search the streets of Rome for a stolen bicycle needed for the father’s profession; is elemental and fable-like in its simplicity. The pulsing humanity, vivid portrait of a still-recovering Roman society, and the naturalistic performances of the amateur cast elevate De Sica’s achievement to one of the most remarkable yet seemingly unassuming in the history of cinema.

The film won another yet another honorary Oscar, and was arguably seen by more Americans than nearly any other previous international film.

Two years later, Italy was home to a decidedly distinct form of cinematic breakthrough. The Venice Film Festival, started by reputed cinephile Benito Mussolini, may have been a picturesque hobnobbing for the international elite, but along with the Cannes and Berlin Film Festival, it shone the spotlight on overlooked cinema from a stunning wealth of nations. In 1950, Venice screened a film from a nation that few Westerners knew anything about: Japan.

Rashomon, directed by a young filmmaker named Akira Kurosawa, was made even more exotic by its medieval, rural setting. It is safe to say that most members of the Venice audience had not seen anything remotely like this vivid snapshot of ancient Japan. However, it was the film’s idiosyncratic, experimental approach to storytelling that was far more jarring. In presenting the aftermath of a brutal murder and rape, Kurosawa offers four perspectives to this twisted saga, complete with detailed flashbacks. Much to the audience’s dismay and bewilderment, however, none of these “sides to the story” offer any sense of closure or coherence. Viewers used to flashbacks filling in the gaps and wrapping up loose ends in the narrative were sideswiped by Kurosawa’s film. By the close of the work, all that is certain is that humanity is a selfish, petty, misleading, and dysfunctional lot. As the years went by, it would become clear that Kurosawa was one of cinema’s greatest magicians, arguably even more so than the esteemed John Ford or Alfred Hitchcock.

These open windows into the wide world of cinema may have seemed like a fluke, but as the decade wore on, it was clear that the floodgates were just being unleashed.

The Boom Takes Hold

In 1953, Venice was once again home to an Eastern invasion, as veteran Japanese filmmaker Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterful Ugetsu transfixed the crowds. The eerie, otherworldly samurai-romance-ghost story was an audacious, perfectly realized achievement. That very same year, Yasojiru Ozu’s Tokyo Story was released in Japan. In contrast to the rural historic setting and swashbuckling samurai, Ozu’s work was a modern, subtle, and ultimately universal look at the generation gap and the big city-small town divide. Despite its ability to transcend its Japanese origin, the film’s distributors did not import the subtle masterwork until nearly 20 years later, partially due to the urging of American critic/filmmaker Paul Schrader. That being said, its domestic release in Japan at the same time of other internationally-known Japanese masterworks indicates what an incredibly fertile period it was.

A year later, a former protege of Rossellini named Federico Fellini broke free from the stifling constraints of the aforementioned neorealism with the magical La Strada. Pairing the versatile, iconic American actor Anthony Quinn (dubbed in Italian) with Fellini’s clown-like, beguiling wife Giuletta Masina, the film combined an unsparing portrait of post-war Italy with the wonder and surreal excitement of the circus lifestyle. While the narrative is based on a simplistic “beauty and the beast” motif, Fellini’s swirling camera, Nino Rota’s sublime musical score, and Masina’s unforgettable performance make La Strada one for the ages. The result was the first official winner of the Best Foreign Film Oscar. The movement had clearly flowered.

Around the same time, a nation with a robust cinematic industry coloquially known as “Bollywood” was tossed a molotov cocktail at its national emphasis on flashy, trifling musicals. The young Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray, aided significantly by the enchanting musical stylings of fellow neophyte Ravi Shankar, unleashed the gritty, achingly intimate Pather Panchali. Delving deep into the tenuous lives of an impoverished rural family in caste-obsessed India, the film paints a universal portrait of childhood, family dynamics, and the futility of existence. Like Kurosawa, Ray would prove to be a masterful, prolific director whose films were far more admired by Western audiences than domestic moviegoers.

As aforementioned, France was a key nation in the development of cinema. However, by the mid-1950s, it had grown stale, despite some international successes as the whimsical yet macabre child’s eye view of World War II, Forbidden Games. Film critics such as Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut tore apart contemporary French film while praising the subversive works of Nicholas Ray or Hitchcock. Challenge to direct a film himself after harsh criticism had him banned from Cannes, Truffaut unleashed the truly groundbreaking The 400 Blows in 1959.

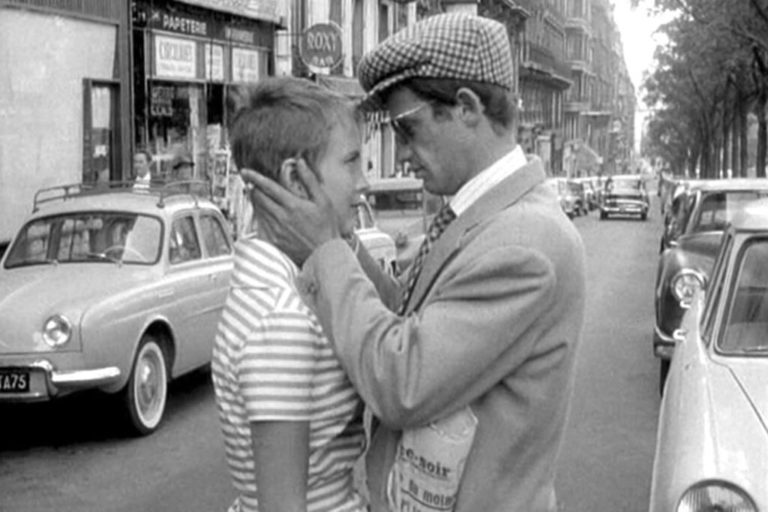

It contained all the honesty and shattering raw emotion of the Neo-Realism films, while simultaneously containing a youthful urgency and freewheeling moments of joy. It netted him a Best Director honor at the very same festival, and launched the movement forever to be enshrined as “The French New Wave.” His colleague Godard crafted an even more earth-shattering debut the following year, based on a rough treatment by Truffaut himself.

Eschewing realism for cinephile references, groundbreaking editing, and a brash, proto-punk attitude, the resulting Breathless took the film world by storm. Relatively light on substance yet still overflowing with lucid images, insightful dialogue, and iconic performances by Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, Godard’s debut repurposed dormant Hollywood genres like gangster and noir for something that was somehow paradoxically fresh. Truffaut would continue to crank out heartfelt works like Jules and Jim and Day For Night, while Godard would turn genres inside out, occasionally producing a work of raw, unfettered feeling, most notably Vivre Sa Vie, starring his then-wife Ana Karina.

The same year as Breathless, Fellini arguably reached his peak with La Dolce Vita. A sprawling depiction of depraved modern Rome, Fellini’s most renowned work invented the term paparazzi, gave one of cinema’s great anti-heroes in Marcello Mastroianni’s weary tabloid journalist, and led to some of modern film’s most repeated (and parodied) images. Similarly emanating from the Italian shore came a vision decidedly different from Fellini’s outrageous flamboyance or De Sica’s warm humanism. Michelangelo Antonioni would later make movies as pretentious as his name, but L’Avventura remains one of cinema’s great enigmas, a moody, existential film that gleefully tore apart conventions. The film experienced a remarkably polarized reaction at Cannes, with half the audience booing and the other half forming a petition declaring it one of the greatest works ever shown at the festival.

Meanwhile, in the small, isolated, climatically dreary nation of Sweden, Ingmar Bergman explored pitch-black themes of the absence of god, mental illness, and profound family dysfunction with a troupe of actors he chose through local theater work. Despite these unorthodox origins and less than commercial topics, Bergman emerged as a giant of international cinema by the end of the 1950s. The Seventh Seal especially became the poster child, and arguably even a self-parody, of the art-house aesthetic with its stark black and white photography, earnest, brooding performances, and deep themes of the inevitability of death and the futility of religion. Yet he continued to make a variety of renowned films until the 1980s, and along with Kurosawa and Fellini he remains one of the primary cinematic purveyors of the art-house age.

The New Hollywood and International Cinema Co-Exist

During the early 1960s, films such as Bergman’s Persona, Fellini’s 8 1/2, and The Woman In The Dunes would prove to be as epochal, life-altering and zeitgeist-defining as “Howl” and On The Road were to the “beats” of the 1950s and as Are You Experienced, Blonde on Blonde, and Abbey Road would be to the “hippies” as the decade wore on. Hollywood, however, seemed to reach an impasse. During the previous decade, the new, shiny threat of television frightened the big studios, who scrambled to make full-color, cinemascope epics like Around The World In 80 Days, Ben-Hur, and The Bridge on The River Kwai.

By the mid-1960s, that was all mainstream American cinema seemed to offer. David Lean, the director of the latter film who started out with the small-scale likes of Brief Encounter and Great Expectations, became punch-drunk with providing mass-scale entertainments, unleashing the era-defining Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago. The Hollywood musical, soon to begin its decline, reached its peak of popularity with West Side Story and The Sound of Music. All these films were box office smashes and won the big industry awards, but it was clear that Hollywood was becoming stale and stodgy. These films had flash and style over substance, color and spectacle but precious little soul or deep thought. College students from Harvard and NYU to UC Berkeley instead were haunting art-house theaters from coast to coast, watching low-budget black and white films from Europe and Asia.

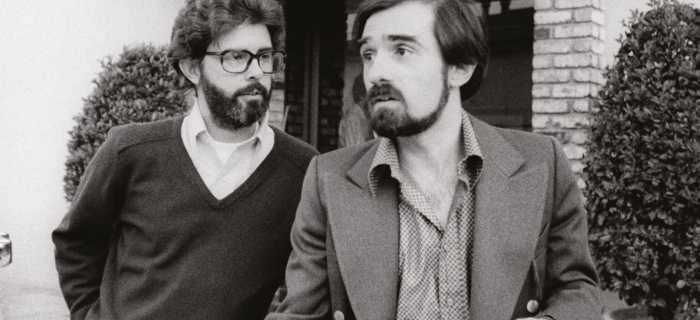

These students were not limited to mere moviegoers. Film schools, a then-novel phenomena, sprouted up in New York and L.A. Among the student population included Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Brian De Palma. These budding directors, more than anyone, worshipped at the altar of Kurosawa, Fellini, Godard, and Bergman.

By the end of the decade, the art-house aesthetic creeped into Hollywood product. Bonnie & Clyde, a gritty, youthful, darkly comic romp directly inspired by Truffaut, per screenwriter Robert Benton, revolutionized filmmaking in the United States. By the dawn of the following decade, the raw, personal, intimate Five Easy Pieces, Mean Streets, and The Last Picture Show unveiled a “New Hollywood,” but this innovation could not have existed without the influence of the international masters who defined a new form of cinematic expression as elemental and powerful as the novels of Kerouac or the proto-punk of the Velvet Underground. Now, it was kinetic urban films like The French Connection and The Godfather which were cleaning up at the Oscars, while bloated “epics” like Ryan’s Daughter failed to make an impact.

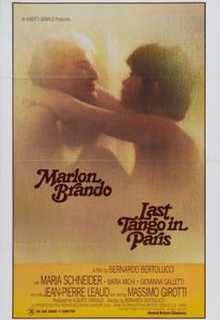

Meanwhile, international cinema continued to prosper. The seismic social upheavals of the 1960s led to a newfound sexual permissiveness in cinema, especially in Europe, as the late, controversial Bernardo Bertolucci took psychosexual exploration to a breaking point with The Conformist and Last Tango In Paris, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, at the vanguard of “New German Cinema” which also included the previously noted Wenders and Werner Herzog, vividly expounded on homosexuality during a prolific run of distinctive films. This cinematic trend, both at home and abroad, was unprecedented in its artistic integrity. Yet, all good things must come to an end, and cinema reverted to its emphasis on commerce, not art, by the end of the 1970s.

The Summer Blockbuster and The Fall of the Art House Dream

One of the members of the new breed of American cinema is now arguably Hollywood´s most beloved living filmmaker, one Steven Spielberg. An acolyte of commercial genre cinema, rather than art-house, he grew up desiring to break into Hollywood, and found work in TV. In 1975, he was tapped to make a quick adaptation of a popular potboiler about a killer shark, Jaws. Starring Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss, who just began to make a name for themselves, respectively, with French Connection and American Graffiti, the production seemed to spell disaster with re-shoots, a ballooning budget, and an inexperienced director seemingly in over his head.

Instead, the film shockingly became a runaway success, ushering a whole new era of summer blockbusters, and was eclipsed by the even higher-grossing likes of Star Wars, made by Spielberg´s close friend George Lucas. By the early 80s, this emphasis on spectacle would be even more pronounced than ever, as art cinema both domestic and international would be swept aside.

These trends roughly continue into the 21st Century, with superhero films and endless sequels dominating the multiplex. However, as aforementioned, milestones such as the Oscars and mainstream attention showered on Parasite and Alfonso Cuarón´s homage to his Mexico City childhood Roma has shown a slow-but-sure comeback for international cinema as of late. It remains to be seen, however, if the world of cinema will ever see such a widespread boom of innovative filmmaking as in the post-war years.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Foreign films are great because they offer a glimpse into cultures that are often overlooked by Hollywood.

Your piece reminded me of how and why I loved ROMA.

[probably one of the first arthouse films I saw on Netflix]

When I got into arthouse cinema; there were films like THE CONFORMIST and ZERO CONDUITE.

Also Miramax brought a lot of the middlebrow and highbrow stuff to people in the 1990s and 2000s.

A good mate has shared silent films with me like NOSERFATU and METROPOLIS.

And those realist Italian films you mentioned from the post-war period.

We were very lucky to experience the American Songbook Musical when we did.

I think of Spielberg’s adventures in film school shown at the very end of THE FABELMANS.

And KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON.

And, yet! RYAN’S DAUGHTER!

Arthouse has also got into the Nobel Prize world. Handke in 2019.

[he gave back some prizes in his time – which was very rock and roll in my opinion].

When I finally saw Rashomon at Cinema 3 [Australian Centre for the Moving Image’s virtual cinema] it was so good.

I also took the opportunity to see some Jacques Dery films – CHERBOURG and ROCHEFORT. This was last Thursday

If I were only allowed one art film to take to a desert island, Andrei Rubliev would be it (with Bela Tarr’s Satantango, a close second).

Give me a list. Which art house movies are you favs?

1. The Magnificent Ambersons

2. Rashomon

3. Don Giovanni (the Joseph Losey version of the Mozart opera)

4. Greed

5. La Grande Illusion

6. Peter Ibbetson

7. Napoleon

8. Le Grand Meaulnes (the 1967 version)

9. Paris, Texas

10. La Chambre Verte

Russian Ark

The time of the gypsies

Elephant

Lost Highway

There will be blood (not ‘arthouse’ enough??)

Synedoche, New York

L’Avventurra

Seven Samurai

Last year at Marienbad

Black Orpheus

I know we are all supposed to love Akira Kurosawa, but I’ve tried and tried to watch these films but could not get into them or enjoy them.

If you weren’t around for the late 80s/early 90s, you would never believe how China completely dominated art house cinema!!! Raise The Red Lantern; To Live; Red Firecracker Green Firecracker; Farewell My Concubine are just off the top of my head. Boy I really miss 80s/90s Chinese World Cinema. What happened?

Agree. China and Hong Kong were at the top during that time period. Love Wong Kar Wai and Zhang Yimou.

John Woo came from Hong Kong too! I saw part of The Killer in film school and it was great. You can definitely see how that led to Face/Off.

Great selections and discussions! On par with the best film school recommendations.

For modern art house directors, I would mention directors such as Bela tarr, Roy Andersson and Yorgos Lanthimos. They all have very definitive style in directing and all have shaped my personal view on cinema. Gaspar Noe as well is worth mentioning since he has been widely recognised with his recent films.

Those are all great directors!

What do you think of Terrence Mallick films?

Biiiiig fan!

I actually started with some of Bergman’s works, moving to Russian directors like Tarkovsky. Have recently started in on the French New Wave directors and will be moving to Kurosawa works soon enough. The Criterion Channel and Letterboxd are in my opinion the two greatest resources for people wanting to start the journey of getting more out of cinema than mainstream actions or dramas.

Wong Kar Wai and Tarkovsky are two of my favorite directors of all time now and have enjoyed everyone of their films.

i miss that they be very few art-house theatre now , even when i was 15 there at least two down one street where i had lived , hardly to bee seen now

My favorite classic art house is Tokyo Story.

I’ve never felt so guilty about not calling my parents as I did after seeing Tokyo Story. Years later, the screening of ANY Japanese film makes me ponder my fundamental failings as a son … I may be traumatised for life.

Ah, Tokyo Story is a lovely film, the scene with the old timers getting drunk in the bar always makes me laugh but is it art house?

Arthouse is tough to define, most, but not all, films not in the English language qualify in UK/USA venues. For English language films it’s harder. A film like Citizen Kane is one of a huge number of great American films that are over 50 years old but were released theatrically. Cinema classics they may be but arthouse in the same sense as Tarkovski or Ozu is a stretch. Welles’ Othello would be a much better choice as an arthouse film than Citizen Kane.

Arthouse movies are films that you need to go to a special cinema to see, they’re not available to watch in “normal” cinemas, but their consumption at a formative age is necessary to the development of an intelligent and culturally aware individual.

When I was a young boulevardier there were certain films that you knew existed (Rashomon, Rubliev, Les Enfants du Paradis, Un Chien Andalou, L’Age D’or, Belle du Jour, The Tin Drum, the nine hour Russian War and Peace) but that you had to diligently trawl the more obscure pages of Time Out to ever have a chance of seeing. (Quite how youngsters in the provinces got on I cannot imagine–I suppose such deprivation goes some way toward explaining Morrissey.)

Nowadays youth has it all far too easy with their Ipods and their Netflix and their YouTubes on which the most esoteric of movies is no more than a click away.

You are as right as right can be.

I’m assuming art house means of little commercial potential upon release?

There was me thinking art house was just a euphemism for nudey movies…

Undoubtedly avante-garde, possibly pretentious, but never boring. Bergman plays around with the format of film, but these aren’t just empty tricks, they build up an amazing level of emotional intensity, that burns through everything.

And the images linger on – easy to parody yes, because it is easily recognizable. It left an indelible mark on the history of cinema.

I’m very tired, and I know that what I’m writing now is heading for pseuds’ corner, but Bergman is great.

Persona anosreP.

Wish you had mentioned German expressionism!

Arthouse or indie films are generally hit or miss fare. While I do like quite a few (e.g. GARAGE, FUNNY GAMES, ANOMALISA, STRAIGHT STORY, CENSOR, PAPRIKA- Satoshi Kon), many of them can be just insufferable such as MIDSOMMAR or SUSPIRIA, the original and remake.

What are some modern art house films people would like to recommend? 2000 to 2023?

The White Ribbon, Climax, Mulholland Drive, Funny Games, Uncle Boonmee who can Recall his Past Lives, The Turin Horse, Dogville, Melancholia.

I think alternating between Godard and Bergman is the best way to get into art house cinema. The greatest challenge for newbies is to find fulfillment from watching experimental and generally absurdist films. The reason why I tell people to alternate between Godard and Bergman is because though both are experimental, their approaches are polarized. Godard’s films generally have plots that are simple but his editing and cinematography is bizarre especially for unfamiliar eyes. On the other hand, Bergman’s films generally have simple yet beautiful cinematography, but the themes he projects are far from straightforward and are always open for your interpretation. I think alternating between the two will help you ease into this brand of cinema.

Funnily enough is that Godard was very fond of Bergman while Bergman himself criticized Godard on numerous occasions.

Arthouse films need to make a serious comeback!

I am sick and tired of all the Marvel Avengers Rollercoaster flicks and I am definitely fed up to the brim with the already exhausted Fast and Furious popcorn flicks!

Enough is enough! We need more arthouse films…NOW!!!

They never left.

Facts, however, it’s no secret that their place within the movie theater had been shoved aside by overproduced big budget films. Not that I want Marvel movies out of cinemas, but I wish wouldn’t have been so hard to find a theater that played the lighthouse and parasite. It’s particularly hard in the US where people couldn’t be bothered with subtitles.

I think one great underrated arthouse director would be Masaki Kobayashi who directed the original Harakiri and the grand “dinosaur” trilogy, The Human Condition. His films are superb.

I have been meaning to take the time to re-watch some of these, now I have a few more to add to the list. Cheers!

For a modern and very personal example of Arthouse films check out the Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan, whose movies won several Cannes awards including the palm d’or in recent years.

Maybe some of the most early works of these directors (that i don’t remember mentioned in this TERRIFFIC video) can be also reffered as Art House:

Jean Cocteau

Jean-Pierre Melville

Carl Theodor Dreyer

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

John Cassavetes

Jan Švankmajer

Alfred Hitchcock

Roman Polanski

The Coen Brothers

Roger Corman

What do you think?

What introduced me to arthouse films is gus van sants final days.

The article brought me back to the Cima time pass for I saw many of the films in the article. I agree people don’t want International films from French and India, however, Korean pop culture for movies is on the rise. The this Oscar Award a Chinese movie won for Best Films. Article is well written informative history of Cima. I enjoy reading.

While increasing global exposure in filmmaking is a good thing, I am still unable to stumble upon a set of interlinked works by directors who are aware of each other’s craft and come up with their own little filmmaking grammar.

I think of the American duo, Jeremy Saulnier and Macon Blair, but they are hardly a “community”.

Outside the USA, perhaps the constellation closest to what I have in mind is the Greek Weird Wave.

Capturing the essence of diverse cultures in movies is like preserving the soul of traditions and manners. Films, as powerful storytellers, have the unique ability to convey the purest traces of each culture, allowing audiences to emotionally connect with the richness and authenticity of their heritage. In a world of globalization, this idea advocates for maintaining the true spirit of cultural portrayals in cinema, making each film a celebration of unique narratives and a bridge to understanding the diverse expressions of humanity.

A good article. While I enjoyed the discussion of different movies, the range of them from The Seventh Seal to Jaws led me to wonder what is limited to being “international.”

International cinema and indie arthouse films give me hope for the future of film. As of right now, Hollywood is so obsessed with quantity over quality, over-saturation of franchises, and whatever will make the most money. I hope that more international films will get the attention they deserve, and show that good-quality storytelling etc. can allow a film to have its imprint in history over how much it made at the box office, or how many famous actors you can squeeze into one shot.

Expertly written!