Autism in Media: Progressing, Yet Stuck

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), 5.4 million Americans live with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). Formally diagnosed autism is more common in some groups than others. For example, males are far more likely to be diagnosed with ASD than females. However, the autistic community encompasses people from all demographics. This includes people who have self-diagnosed after lengthy personal research and soul-searching. They may choose to seek a formal diagnosis, but may not, out of concern that they will be stigmatized if they publicly say, “I’m autistic.”

Broadly defined, autism is “a complex, lifelong developmental disability that appears in early childhood and…[impacts] a person’s communication, social skills, relationships, and self-regulation”. 1 Autism is a “spectrum disorder,” meaning all these factors are affected in different ways. The autism spectrum also includes conditions like Asperger’s syndrome, a “milder” form that is not currently recognized as autism in the DSM-V.

Non-autistic or “neurotypical” people tend to categorize autism or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) with words like “mild, moderate, or severe.” However, autistic people prefer the use of “spectrum.” They reject the idea of “having” mild or severe autism because autism is not something they have, like a disease or an injury. It is an identity, a major contributor to who they are.

Autistic people and the autism rights movement have gained plenty of steam in the twenty-first century, thanks to increased voices from the #actuallyautistic community and campaigns like #boycottautismspeaks or #redinstead (a response to the Light it Up Blue campaigns often seen in April, Autism Awareness Month). As autistic voices become stronger, media representations of autism have increased. Representations that existed before the movement gained steam are talked about more, and more media consumers are finding kinship with characters who are “coded” autistic, even if they’re not named as such.

Current representations of autism in the media have given people plenty to identify with and discuss. Thanks to autistic voices, representation is now more nuanced than it has ever been. There are several highly developed, sympathetic autistic characters for consumers to meet in the media now. However, media representation of autism still struggles with some old, familiar problems. In many ways, autistic representation is progressing and “stuck” at the same time. Many of today’s autistic characters do a great job representing this dichotomy.

For the purpose of our discussion, a character is autistic if he or she is named as such–that is, if the character themselves or another character says, “I/Character am autistic/has autism.” The character is also autistic if he or she exhibits several traits of autism, but is not named as autistic. In that case, the character is “coded” autistic, meaning the subtext of the character or his or her environment signal the person could be autistic.

In our discussion, we will use the terms “autistic person” or “autist” rather than “person with autism.” Many autistic people prefer the former terms, eschewing “person with autism” because they feel the phrase separates autism from them, as if autism is negative. We will use “disabled person” for the same reason, and “abled” or “non-disabled” to describe non-affected individuals. Non-autistic or non-disabled individuals may be called “neurotypical,” while their counterparts may be called “neurodivergent.” Again, these are community-preferred terms. They focus on diversity rather than preconceived ideas of normality.

Finally, this discussion covers ableism. Ableism is defined as discrimination against disabled people, or more specifically, discrimination based on a preference for able or typical bodies and minds. Ableism can be direct (“He’s autistic and not going to get better, so he shouldn’t be around patients”), or “softer” (a pitying attitude, surprise that a neurodivergent individual can do the same things as neurotypical people, inspiration porn or assumptions that disability is negative or a lesser state).

Sherlock Holmes, Associated Stories, Novels, and the Sherlock TV Series

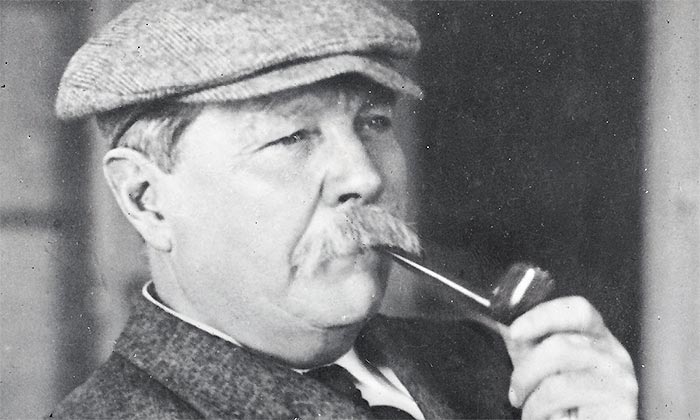

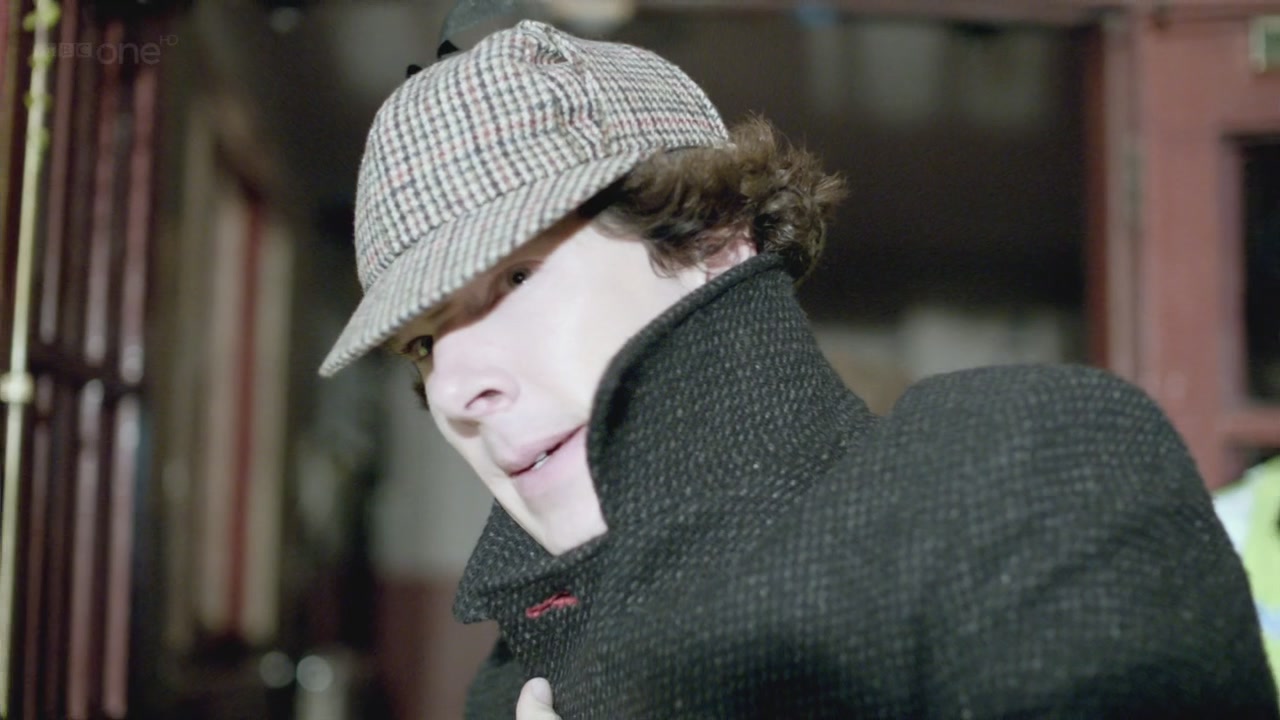

It’s fitting to begin our discussion with Sherlock Holmes, who might be the oldest and possibly first autistic character in any media type. The famous detective first appeared in Arthur Conan Doyle’s short story “A Study in Scarlet” in 1887. In the ensuing years, Doyle wrote 56 more Holmes stories, including a novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles. In 1893, he attempted to kill Holmes, setting up a final showdown with nemesis Dr. Moriarty in “The Final Problem.” Holmes was resurrected when the public begged Doyle to bring him back. Not only did he return in more short stories, but he was eventually the protagonist of TV and movie adaptations. The most recent is Sherlock, a series created by Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, starring Benedict Cumberbatch.

Holmes is never called autistic either in his original form or Cumberbatch’s interpretation. This keeps the original incarnation historically accurate; no one would be called autistic in Victorian London because autism spectrum disorders were unknown. However, Holmes’ peers know he is noticeably different from the general population, and they do comment on it, for good or ill. Holmes’ characterization also gives us a mountain of evidence that our favorite detective lived with autism long before anyone, including himself, would have figured it out.

As for the television series, it’s still set in London but is a modernized version of Holmes stories (the series ran in Britain and America from 2010-2017, but experienced a long hiatus and is considered cancelled). Within the series, there are nods to the fact Holmes could be autistic. Both he and Watson make sarcastic references to Asperger’s syndrome at least once. However, neither Holmes nor anyone else is comfortable claiming the distinction or any form of ASD as an identity. Therefore, the original Sherlock and his twenty-first-century counterpart are coded autistic, though heavily so.

Classic Character, Classic Traits

Of all the characters in our discussion, Sherlock Holmes may have the most classically, or well-recognized, autistic traits. He is a prodigy not only at detective work, but in all fields, from math to science to literature. Not all autistics are prodigies, but the key is, Sherlock doesn’t apply his personal interest to every field in which he excels. Sherlock’s interest is highly specialized; he focuses on solving cases and using whatever acumen he needs to do so. Furthermore, his specialized interest is not only about detective work. Detecting is Holmes’ job and vocation, true, but he would be happiest solving any puzzle, answering any complex question, or using deductive reasoning in any context.

This comes up in a lot of Holmes stories, if not every single one. Holmes does it so often, The Hound of the Baskervilles’ opening scene is built around it. Holmes’ latest client, Dr. Mortimer, is a country doctor, but doesn’t get a chance to mention his occupation. Instead, Holmes deduces it and explains how he did so, using the wear and tear on Mortimer’s shoes (more indicative of walking on say, grass and dirt or gravel than cobblestones or pavement). He goes on to deduce Mortimer is well-entrenched and well-liked in the profession, given that he carries a cane with a local hospital’s signature engraving. The engraving indicates the cane was a gift, and its decorative embellishment suggests such a gift is given only after significant service to the indicated hospital. Additionally, the cane is in great shape, suggesting Dr. Mortimer is, too; he’s middle-aged but not yet in need of mobility aids.

Besides his penchant for deductive reasoning, Holmes exhibits autistic traits in his socialization and lack thereof. He does have a social circle and support system. Dr. John Watson is his frequent visitor and best friend. He has at least one living relative, a brother, Mycroft. He gets along well with Detective Inspector Greg Lestrade, and in the modern series, has a fairly amicable relationship with DI Stella Hopkins, although he finds one case she asks him to assist on boring and not worth his time. His housekeeper, Mrs. Hudson, acts as a mother figure especially in the series. Although the original stories don’t give Holmes a love interest, he also develops a friendship with Molly Hooper, and respect for Watson’s love interest and eventual wife, Mary. However, unless these people are helping Sherlock with a case, most of them aren’t major presences in his life. They don’t socialize casually as neurotypicals usually do. Additionally, Sherlock doesn’t seem to relate to his inner circle outside of his work. Every conversation circles back to the problem at hand, which works for the genre but lends credence to the autistic coding, too.

Finally, many of Sherlock Holmes’ mannerisms lend themselves to autistic coding. As TV Tropes points out, one of the biggest is his “Brutal Honesty.” Like many autistics, Holmes tells the truth whether it’s “socially appropriate” or not, because they believe or were otherwise taught the truth is paramount while feelings about the truth are secondary or irrelevant. And like many autistics, Holmes is chastised, arguably unfairly, when he misreads the silent social signal to keep his opinions to himself. He will tell a small child about cremation rather than entertaining the child’s belief in Heaven when a beloved grandparent dies. He will outright call someone a liar when that might be true, but not the best way to glean information or build temporary rapport.

Besides his brutal honesty, Holmes reads as autistic based on his ever-present, sometimes overly engaged, logic. This doesn’t mean he lacks emotions or empathy, as we’ll explore next. If anything, the logic serves Holmes well. In one series episode, he used it to come up with no less than 13 ways to outwit Moriarty. Additionally, Holmes’ reliance on logic can help him separate his emotions from the case at hand when needed. This is especially useful when it comes to women. Several females, including suspects like Irene Adler, are attracted to Holmes both in stories and the TV series, sometimes desperately so (see Molly Hooper). But as creator Steve Moffat once said, Holmes is “swallowed in his work” and “doesn’t have time” for romance. His lack of interest can come off as cold, but for Holmes, it’s a combination of protective mechanism plus a way of maintaining focus. Like many autistics, once Holmes gets focused on something, he wants and needs to see it through. Thus, intensity, sometimes almost one-track-mindedness, is not only required but helpful.

Solving the Ongoing Case of People

Arthur Conan Doyle didn’t write Sherlock Holmes as autistic, or consciously code him as such. Series creators Moffat and Gatiss may not have either, but they did a great job of exploring coded autistic emotions with Holmes. At times, Holmes does skirt the line of cruelty, and has been accused of being a sociopath, as have other autistic characters we’ll meet. But just as autistics express emotion and empathy differently from neurotypicals, so does Sherlock Holmes.

What’s interesting about the portrayal of Holmes’ autistic emotions is that he appears to “solve” emotions like he solves mysteries. Sometimes, like real autistics, Holmes is “coached” on social interaction. For instance, Watson will tell him he’s committed a faux pas or try to warn him of what not to do before the duo meets someone. But with or without direct coaching, Holmes will examine, analyze, and learn from interactions on his own. For instance, he’s unintentionally, but notably, cruel to Molly Hooper during “A Scandal in Belgravia.” In several other episodes, he’s brusque and dismissive with her, too. Yet once he realizes what he’s doing, Holmes does try to make amends. He does recognize he processes information differently from neurotypicals, to the point that during his childhood, he felt lesser and stupid.

Additionally, he recognizes he sometimes uses his intelligence to manipulate others, and is truly penitent when that happens. In other words, Holmes wants to relate and empathize, but either can’t or won’t do so without compromising selfhood. Having felt like “different and less” as a child (as opposed to the modern phrase “different, not less” that Dr. Temple Grandin linked to autism), Holmes is clearly determined not to be less again. If it means coming across as cold, that’s worth the sacrifice to stay secure in his acumen, memory, and other good traits.

The Puzzle of Holmes’ Autistic Coding

Sherlock Holmes might be the most obvious, “loudest and proudest” autistic character in the fictional universe, whether the word is used or not. Plenty of fans on the spectrum, this writer included, can find some way to identify with him. Fans on and off the spectrum can also admire Holmes without crossing into the soft form of ableism, because his abilities are so far beyond most of us, ASD, other disabilities, or not. However, Sherlock Holmes’ autistic coding has some flaws that keep him from being a fully “good” representation of real autistic people.

While we can’t fault Doyle for failing to represent what he didn’t know or understand, we can analyze the flaws in Benedict Cumberbatch’s Sherlock and the choices of his creators. Perhaps the biggest flaw is that, more than other autistic characters, Sherlock Holmes is meant to be viewed as a puzzle more than a person. In some ways, this ties in to his talent for solving puzzles. That is, Holmes may well think of himself as a puzzle, and that might be okay. It’s a bit like the phenomenon of disabled people making jokes about disability at their own expense. But at the same time, Holmes’ creators and the fictional people around him seem more intent on looking at him or figuring him out than relating to him. Others become so used to coaching or warning Holmes about how to handle emotions, for instance, that they sometimes forget he is an actual person with emotions. Others’ tolerance for Holmes’ processing is varied; at times, it seems Holmes’ compatriots would rather marvel than understand.

A similar problem occurs because of Holmes being coded autistic in a modern world rather than called such and making autism a part of his identity. Again, it’s okay that Arthur Conan Doyle didn’t use autistic vernacular because of his era. But since Sherlock the series is set in modern times, and since their Sherlock Holmes exhibits so many autistic traits, the question becomes why the creators didn’t allow Holmes to “really” be autistic. Their choice means that Sherlock’s autistic traits blend into the rest of the story well, but perhaps too much.

In other words, it’s okay if the modern Sherlock Holmes isn’t being called autistic in every episode. If the creators and writers did that, autistic and disabled viewers might well call foul, because it would come off phony. Plus, drawing attention to Holmes’ autistic traits would pull it away from the mysteries embedded in the stories. If anything, because Sherlock–character and show–are so centered on mysteries, it might be difficult to bring in too many character arcs. But again, it seems off to create a character within whom so many could find representation, yet never address that aspect. It’s difficult to say if the intent was to create, then erase, a coded autistic character, but the potential exists and is disturbing.

Finally, a lot of viewers who see autism in Sherlock might be frustrated the protagonist is a white male. The demographic probably was not a conscious choice. The original Holmes was a white male in a time when that was one of the only acceptable protagonist demographics. And as noted above, most of today’s autistics do fit the white male demographic. Autistic males outnumber females by more than 3:1, and finding statistics on autistics from other minority groups can be next to impossible.

In many cases, minorities who have been diagnosed as autistic don’t claim the distinction if they can help it. Once “out,” autistics are more likely to be bullied, suppressed, and forced to behave as neurotypicals than understood. Even autistics who don’t get diagnosed until adulthood–thereby avoiding some childhood pitfalls like forced therapies–may not reveal themselves. If they try, they are often shut down. This writer has been shut down softly–“No, you’re too socially appropriate”–and with blatant ableism–“Oh, that explains why you refuse to do what everyone else knows how to do.”

Despite all this, viewers can and should still question why the Sherlock Holmes of this century still fits the white male mold, and the somewhat stereotypical prodigy mold to boot. At least two of the major secondary characters in Sherlock are gender-flipped, played by women rather than men. Those women, both on the police force, are women of color, too. Watson’s sister Harriet goes by Harry and is a lesbian. The show makes plenty of room for discussion of Harry’s orientation, plus the possibility of other, more covert LGBTQ+ leanings. The question becomes then, why autism, thus disability, is somehow not okay when other minority statuses are accepted. There is a sense that if Holmes did not fit the “majority autistic” demographic, the autistic coding might be downplayed or removed as much as possible.

Adrian Monk, Monk

Long after the classic Sherlock Holmes appeared on the final page of his stories, but before Benedict Cumberbatch’s version, viewers met Detective Adrian Monk. Monk and the characters around him are heavily based on the Holmes universe. Monk is, of course, Sherlock Holmes in the world of early twenty-first century San Francisco. He has a brother named Ambrose who fills the role of Mycroft Holmes. Monk’s boss, Captain Leland Stottlemeyer, fills the role of DI Lestrade, and Monk’s assistants Sharona and Natalie are female Watsons. However, Monk’s universe and character are more in line with ours than the more “classic,” scholarly, and ever-stoic Holmes of London.

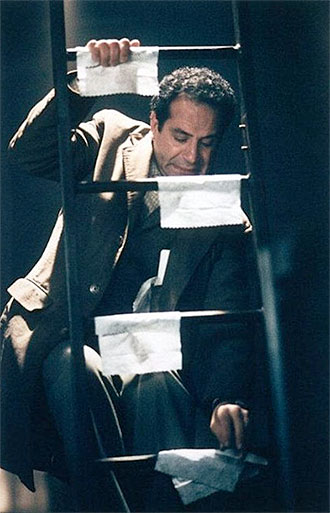

Adrian Monk’s eponymous series, created by Andy Breckman, lasted eight seasons on USA, starting in 2002. In many ways, Adrian Monk, played by Tony Shalhoub, opened up the conversation about autism and ASD, making ASD characters normal, respected, and possible.

Adrian Monk is never called autistic, perhaps because he is given another named disorder. Monk has been diagnosed with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), a somewhat life-altering case that got worse after his beloved wife Trudy was murdered. That said, Monk has characteristics that don’t fit the classical presentation of OCD. If anything, they fit under the ASD umbrella. Therefore, Adrian Monk is coded autistic. Some viewers have specifically diagnosed him with Asperger’s Syndrome.

Monk is an interesting character whose autistic traits often meld with his OCD presentation. For instance, Monk is deathly afraid of germs, which means he won’t shake hands or make physical contact without a sanitary wipe handy. Yet he finds social interaction difficult even if germs are not an immediate issue. Monk is also pantaphobic. While multiple phobias are not necessarily autistic traits, Monk’s phobias make it difficult for him to feel safe, try new things, or pursue many interests. Thus, the interests he has, Monk commits to on a deeper level than most neurotypicals do. Monk’s OCD makes him dependent on routine and leery of change, something many autistics experience with or without OCD.

Compulsively, Autistically Great at Being Himself

Adrian Monk is written in such a way that his OCD/ASD are assets in almost every situation. This is partially because Monk is a homicide detective who has consulted for the San Francisco Police Department since a psychiatric discharge prior to the series. Detective work is Monk’s major passion, and it demands tireless attention to detail and careful analysis. Yet even when Monk is not actively, consciously working, his OCD/ASD proves more a help than a hindrance.

Monk’s neurodiveristy often helps and hinders him at the same time, a combination many neurodiverse characters since have not experienced. Monk often needs to become fixated on something that seems inconsequential to solve a case. A great example is the Season One episode, “Mr. Monk Takes a Vacation.” During said vacation, Benjy, the eleven-year-old son of Monk’s assistant Sharona, witnesses a murder. The catch is, every time he, Monk, and Sharona come close to finding out what happened, the body is moved. Worse, the crime scene is as clean as if no one had ever been there.

The vacation becomes frustrating and downright miserable for Monk. He’s already uncomfortable with the beach setting, a place “typical” people find fun and that Monk resents being reminded, he doesn’t. A comedian visiting Monk’s hotel makes him the butt of an entire act, and Benjy is depending on Monk, as the only person who believes him, to solve an impossible murder. But Monk is so distracted and fixated, he can’t figure out how the murder occurred, or if it did, why and how to prove it.

The case comes down to the wire, with Monk being given an hour to find evidence and check out, or risk the disgruntled hotel owner having him arrested for trespassing. Monk retreats to his uber-clean hotel room to try clearing his head, Benjy and Sharona close by. Benjy complains the constant odor of disinfectant bothers him, and Monk fixates again, noting at least four maids had to clean the room to meet his standards. But the fixation moment is when Monk solves the case. A gang of hotel maids are cleaning up, literally, through insider trading tips they’re stealing from guests. They murdered a compatriot when she grew a conscience, and have been moving her body, as well as using agents like quick lime to cover up the deed.

Most neurotypical characters, even his assistants and coworkers, expect Monk only to fit into a detective role, or function well in a position where he can give vent to all his atypical characteristics. Actually though, Monk’s neurodiveristy often means he can fit into unexpected roles and solve cases, thus help people, more effectively.

Friendships Done the Monk Way

A classic example occurs in the season three episode “Mr. Monk and the Employee of the Month.” Monk ends up going undercover at a local Mega-Mart to solve the murder of an employee who, by all accounts, didn’t have any enemies or much of a life outside her job. The case gets stickier when it appears the murderer killed so they could be Employee of the Month. After all, who would “commit cold-blooded murder” so they could get a ceramic mug, a plastic plaque, and a gift certificate, only good on weekdays, to a family all-you-can-eat restaurant?

At first, Monk appears as awkward as usual in his undercover position. He repeats the standard greeting, “Have a Mega-Mart day” in a shy, stiff tone. He tries to befriend and get information from a fellow employee, but ends up alienating her. But his perfectionism–or “profectionism” as the employee puts it–proves an asset as Monk finds the exact pair of shoes a customer wants, throws himself into a simple clean-up, and meticulously, almost lovingly, prices every item.

In addition, Monk’s dedication to his Mega-Mart role puts him in a better position to relate to and assist security guard Joe Christie. Like Monk, Joe has lost his SFPD position, although in his case it was because of a false accusation. Although Monk believes said accusation initially, he quickly comes to understand Joe is an honest person who is as eager as Monk to solve the murder. Since Monk doesn’t trust or open up to others easily, this is a key piece of character development for him. Again, it wouldn’t have happened if not for his neurodiversity and particular skill set. In fact, Monk and Joe end up working well together, and Monk ends up exonerating Joe as well as solving the Mega-Mart case. When Joe gets his badge back, he makes clear he’s rooting for the same to happen for Monk someday.

Emotions Done the Monk Way

Besides his obvious talents, Monk is written so that his emotions and self-expression make sense inside a coded autistic personality. Viewers with emotional disabilities of any kind, but particularly autism, find this important because autistic people are often accused of having no emotions. More often, they’re accused of having no empathy. Thus, they’re labeled as everything from selfish to sociopathic, or even potential killers (ex.: Adam Lanza, the Sandy Hook shooter who was allegedly autistic and whose mother wrote sympathetically about his violent tendencies in her blog). At times, the media takes the “no empathy” stereotype to the extreme, painting autistic people as combinations of Sherlock Holmes and Rain Man. As in, these people are so unaffected by everything around them, they speak and act almost like robots.

At various points in his series, it seems like Monk might fall into the same trap. He’s accused of lacking empathy or sympathy several times, and his accusers have great points. For example, when Sharona opens up about her phobia of elephants in “Mr. Monk Goes to the Circus,” Monk tells her, “Suck it up.” He honestly doesn’t know why his reaction is cruelly ironic. Several seasons later, Monk laughs it off when his other assistant Natalie expresses a fear of voodoo and speculates it had a hand in her husband’s death. He also tends to react with more skepticism than normal to Lieutenant Randy Disher, who in fairness has some odd theories about crime, but is sincere in them and often right. If they aren’t directly helping or showing interest in him, Monk struggles to relate to people in almost every context.

However, this doesn’t mean Monk lacks emotions or empathy. If anything, there are times one could read him as an empath. Monk may not be able to identify with every facet of someone else’s situation, but he does recognize, “This makes me feel bad, so I imagine it makes other people uncomfortable, too.” Monk’s problem is that he gets so busy relating to others’ situations on his terms, he actually “empathy overloads” and comes across as thinking, “Your situation is about me.” Natalie’s fear of voodoo is a good example, in that Monk actually empathizes with her fear and grief over her husband Mitch. Emotionally, Monk still “lives” in the same place, because he doesn’t know who killed his beloved Trudy or why, and fears he never will. But because Monk is so intellectual, he can’t relate to the voodoo aspect of Natalie’s experience. He relates to voodoo as a silly superstition, the only way he knows how. Thus, again, his unintended message becomes, “How I feel and react is more important and more understandable.”

Autistic and Filled With Love

Empathy overload is a common problem for those on the spectrum. This writer, for instance, has had it happen to her a number of times. Yet where this writer and other real people struggle, Monk can and does make empathy overload work for him. It’s especially apparent in relation to Trudy. Monk’s deceased wife isn’t a direct part of every case, but she’s always in the background, driving Monk forward and giving him a reason to interact with the world even when it’s debilitating to do so.

Trudy’s loss, the one case Monk can’t solve, often influences him to take on other cases. Monk never specifically asks, “What would Trudy want” or “What would Trudy do,” but again, their love motivates him. He sometimes draws physical strength from her, such as when he cuddles with a pillow of hers that he keeps in a slipcase so it won’t lose her scent. Some of his cases are also directly tied to either finding Trudy’s killer or remembering how she lived her life. For instance, Monk solves a murder at Trudy’s old prep school, goes undercover as an inmate so he can get information from someone with ties to her killer, and helps clear Willie Nelson’s name because Monk and Trudy both enjoyed his music. Monk also tends to work harder on cases involving victimized women, especially those killed in violent manners or without a particular motive.

However, viewers shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking Monk’s message is, “This man was obsessed with his wife” or “Autistic people can only expect saints like Trudy to tolerate them.” Trudy is a bit saintly, which can be problematic at times. But the underlying message of her relationship with Monk is, she did what a good spouse does for any person, autistic or not. Trudy brought out the best in Monk and accepted him as he was. Thus, even after losing her, Monk is able to maintain a view that says, “I am worth something. I am needed and wanted in many ways.” Additionally, Trudy helped Monk see the world could be good, despite–and perhaps with–all the worst examples of human behavior he deals with every day. Again, even after Trudy’s death, Monk recalls what she showed him. He may slip into the doldrums, as anyone would–and more often than most people, at that. Yet, Monk remembers a world with people like Trudy in it can be, has to be, good. The overall message of his love story becomes, “Ours was, and is, the kind of relationship any person of any neurological or ability level can and should have.”

Intrepid Yet “Inspirationally Disadvantaged”

In Adrian Monk then, we have a coded autistic, brilliant character who, socially awkward or not, positively influences the people and world around him. We have a character who experiences deep love and loss, and whose social circle, while smaller than most, is tight-knit and vital to his growth. Can we then say Adrian Monk is a perfect coded autistic character, or flawless representation of autism?

A close analysis would reveal, “no.” Andy Breckman and his fellow creators tried, perhaps harder than the creators of The Good Doctor, to show a neurodiverse person living a multifaceted life. Adrian Monk does not directly fight to “overcome disability.” He seems more accepted than Sherlock Holmes, and more able to relate to neurotypical people. Yet parts of Monk’s portrayal are problematic, too. Interestingly, Monk can be the most problematic when it doesn’t mean to be.

Adrian Monk sometimes falls into the trap of being “inspirationally disadvantaged.” This is a common trope and cousin to inspiration porn, but a bit sneakier because unlike inspiration porn, “inspirational disadvantages” are less obvious in their objectifying of disabled people. When we call Adrian Monk inspirationally disadvantaged, we mean he’s placed in a position where viewers are meant to look at him and say, “His life is so hard; what am I complaining about,” or, “If he can cope, I can cope.” Sometimes viewers are meant to say, “I’m amazed a person like him functions as well as he does.”

The trope often pops up alongside Monk’s phobias or obsessive-compulsive tendencies. Specifically, Monk often achieves acceptance only if he acts like or agrees with “abled” people. At least twice, in the episodes “Mr. Monk and the TV Star” and “Mr. Monk and the Sleeping Suspect,” Stottlemeyer, Disher, and others pressure Monk to agree with their interpretation of a case. Both times, Monk caves in because he can only offer misgivings based on tiny details or inconsistencies. Monk’s colleagues send the unintended but clear message, “You’re only disagreeing because your OCD is acting up.”

When Monk accepts a popular TV star’s clean polygraph, or the fact that a case’s prime suspect is comatose, he’s congratulated, patted on the back, and treated like a colleague on equal footing. If instead, Monk insists his theory is correct, his inner circle will pull back, saying things like, “You’re brilliant, but not always right.” One has to wonder, if Monk did not have documented disabilities, would his interpretations be discounted, or would they immediately be considered more evidence of brilliance?

Something similar happens in the face of Monk’s phobias. Because he has so many, Monk encounters at least one phobia an episode. The way the phobias are handled is a toss-up. Sometimes they humanize Monk and let the audience laugh with him, as during “Mr. Monk Takes Manhattan.” In that episode, Monk stops his trademark summation to chastise a busboy he had seen urinating in a subway earlier. The audience laughs because they recognize, of course Monk would think urinating in a subway is gross–because most people think so. They laugh because in chastising the urinator, Monk does something most of us want to do but wouldn’t dare because it might look petty or strange.

Unfortunately, Monk’s phobias are just as often set up as a reason to laugh at him, or make the audiences think, “He’s so brave for trying to cope.” Part of this comes from Monk’s reactions; when confronted with a phobia, he often cringes and whines like a little child. Additionally, it takes extreme “treatment” for Monk to “overcome” his phobias, such as strong medication or hypnotism. The latter treatment actually has Monk revert to acting like a seven-year-old. In examples like these, Monk gets infantilized, and the abled people around him get more fodder for their case, “Adrian Monk is not like us” or “Adrian Monk is not human or adult in the same way we are.”

Of course, when Monk temporarily overcomes a phobia, he’s treated as competent again–until the next phobia pops up. Then Monk has to overcome again, prove himself again, and continue in the same vicious cycle. Worse, every time the cycle happens, Monk’s inner circle feels justified in acting like their soft ableism is Monk’s own fault. After all, if he would try harder to deal with his disabilities, he would fit in better and others would like him more.

What Part of “Neurodivergent” Don’t You Understand?

To Monk‘s credit, the show rarely puts Monk in a situation where he has to weather constant, blatant ableism. The times this does happen–someone calls Monk a “freak” or uses his quirks against him–someone like Sharona, Natalie, or Stottlemeyer will usually step in and order the ableist to cease and desist. Additionally, when Monk discusses bullying or abuse he’s faced in his life, the audience is meant to feel sympathy. Monk is not brave for getting out of bed and remembering his own name, as disability activist Stella Young once put it. But he is brave for continually confronting his trauma and integrating it into his life in a way that allows acknowledgment and forward movement.

But although blatant ableism is rare in Monk, the soft kind is almost constant. That is, people outside Monk’s daily life are constantly surprised he can function as well as he does or at all. They question or express anger at his quirks, in ways they might not if the same quirk came from a person who wasn’t visibly neurodivergent or disabled. They assume the worst even after Monk’s OCD and autistic symptoms are somewhat explained. For instance, in “Mr. Monk and the Marathon Man,” Monk wipes off his hand after shaking hands with a long line of people. The last person happens to be a Black man, and it’s assumed Monk is a racist. When Sharona attempts to explain, Monk’s acquaintances will have none of it.

Far more often though, Monk’s OCD/autism is not explained at all. In eight seasons, it’s never explained fully. Monk doesn’t advocate for himself, and characters like Natalie and Sharona only explain away the disability facet happening in front of them. In a way, this is okay. If the show stopped to give a speech on OCD or autism every time Monk exhibited a symptom, viewers would quickly get bored. They might get angry, feeling they’re being preached at and tacitly told, “Everybody but Monk is an ableist jerk.” However, plenty of viewers have also asked, “Why doesn’t Monk or anybody just come out and say he has this or needs help?”

We can’t assume that if Monk advocated for himself, his journey would get easier. This is somewhat addressed in “Mr. Monk and the Missing Granny,” wherein the law student Monk hired offers to help get him reinstated. The catch is, reinstatement can only happen if Monk claims discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The idea shakes him to the core. “Am I…disabled?” he asks, as if an affirmative answer would shatter his fragile self-esteem. This is problematic on two counts. One, disability is presented as a horrible circumstance, something that prevents people from being their full selves. Two, the trajectory of the show does nothing to disprove the above, and the idea of Monk being reinstated under the ADA makes it a pity or anger issue. As in, should Monk accept reinstatement under the ADA, the question would arise: was he reinstated on merit, out of pity, or because the SFPD feared backlash?

Different Autist, Same Problems

If Monk had always been accepted as neurodivergent/disabled, to any degree, controversies like the one in “Missing Granny” might not have happened. If Monk had been allowed reasonable accommodations on a regular basis, he might be a stronger and better representation of disability, especially a coded autistic character. Instead, the show’s overall message remains stuck at, “Disability is different, and different has to be bad to be believable.” Viewers only meet Monk after he has experienced a nervous breakdown and been discharged from the SFPD. From that point, he is always tacitly judged on how “high-functioning” he can appear in any given situation. The “high-functioning,” murder-solving, observant Monk is treated with respect and warmth. The phobic, compulsive Monk is separated out, treated as lesser and sometimes subhuman. The separation opens the door for debates about “functioning labels,” which most actually autistic people despise.

In addition, Monk as a character and show faces a lot of the same problems Sherlock Holmes does. Like Holmes, Monk is a well-developed, coded autistic character, but is a white male. The underlying message, “White males are the best autistic voices,” continues.

For Monk though, the major problem in his representation is a lack of growth. The actual trope, called “Status Quo is God,” is present in any episode where Monk appears to make progress. For instance, Monk makes great emotional strides while fostering toddler Tommy Glaser in “Mr. Monk and the Kid.” He acknowledges Tommy can’t stay with him forever because of his disabilities, which is fine. The problem is, Monk doesn’t retain his emotional progress; losing Tommy returns him to his default state, where OCD and autistic tendencies rule his life. Similarly, in “Mr. Monk and the Naked Man,” Monk says he made a breakthrough regarding his phobia of nudity. And indeed, he does confront deep-seated prejudices against nudists. But he never again shows comfort with the body, his own or someone else’s. He never refers to breakthroughs with his other phobias, either. As he tells psychologist Dr. Bell in a late episode, “I’m back on square one. It’s nice to be home.”

The times Monk acts like a neurotypical person, it’s either played for laughs or set up as something that can’t last because it’s not good for him. This happens at least twice, in “Mr. Monk Takes His Medicine” (season 3) and “Mr. Monk Gets Hypnotised” (season 7). In both cases, Monk exhibits childish or risky behavior. He buys a sports car he has no license to drive, acts insubordinate at crime scenes, and in “Hypnotized,” gives a summation in which he claims a killer died of embarrassment because his female captive “had seen his hiney.”

In both cases, Monk gets treated like a joke, or a borderline scary aberration. His “friends” spend both episodes fretting or engaging in the trope “We Want our Jerk Back” (or, “We Want Our Compulsive Detective Back.”) These storylines and attitudes raise the questions, why is Monk never a regular person, no matter what state he’s in? Why, in over four years, is he denied progress? Why is he only considered “better” when he also behaves as less than what and who he is? And, why is acceptance of Monk as a person tied to his behavior? Moreover, the overarching question becomes–what does Monk, the show and the person, really say to actual autistics? The message becomes convoluted, but the crux is: “We accept people with autism and other disabilities to the extent they can act like, inspire, or impress us.”

Shaun Murphy, The Good Doctor

What if an autistic character is not a version of Sherlock Holmes, or more broadly, not a genre-specific character? What if they actually call themselves autistic or are called or diagnosed so by others? In these cases, does the character’s chance of being a fair representation of autistics improve? The answer is a mixed bag and difficult to pin down, as we’ll see with our other characters, starting with Dr. Shaun Murphy.

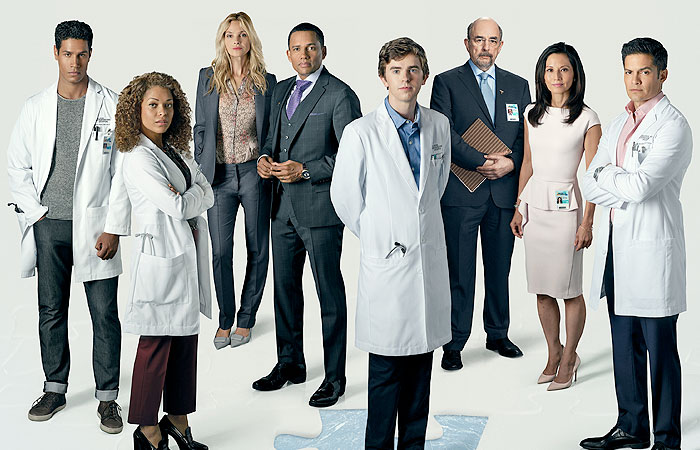

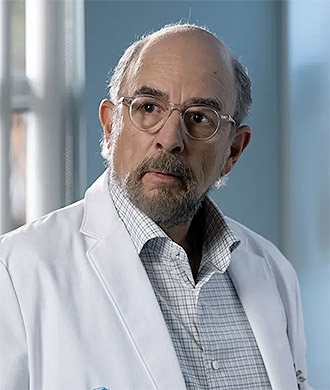

Shaun Murphy, medical resident and protagonist of David Shore’s drama The Good Doctor, appeared on television screens in 2017. Four seasons later, Dr. Murphy, played by Freddie Highmore, remains a vital presence in the fictional St. Bonaventure Hospital and in the world of autistic characters.

Shaun is a medical prodigy and has been called a medical version of Sherlock Holmes, rather like Dr. Gregory House in the eponymous series that preceded The Good Doctor. However, unlike House, Shaun Murphy is pretty comfortable with his personhood, including ASD. He calls himself autistic or says he has autism, often leading with that fact as a key part of his identity and explanation for why he does what he does. Other characters, such as hospital president Dr. Glassman, also refer to Shaun as autistic. Again, it’s usually one of the first characteristics others bring up.

Diagnosis: Autistic and Competent

Shaun displays some “classic” autistic characteristics. Autistic people are sometimes described as having “formal” or “stiff” speech; Shaun’s is so much the latter, critics have described him as speaking like William Shatner. He tends to introduce himself as “Dr. Shaun Murphy” instead of “Dr. Murphy,” and sometimes uses larger or more complex words than usual outside a medical context. If upset, Shaun may repeat himself several times, often out of a conviction he’s not being listened to or understood. He often asks colleagues or patients questions that are inappropriate to the moment, such as about their sex lives or whether they have ever had certain potentially embarrassing symptoms or injuries (e.g., symptoms involving the bladder or bowel).

In addition, Shaun Murphy’s world is narrower and more focused than a neurotypical’s usually is. His work is medical, but so is his main interest and hobby; he can be seen enjoying medically-related activities even when not at work. He’s comfortable with a rigid routine, and hiccups in that routine like a late bus cause him varying degrees of distress. He gravitates toward certain familiar and comforting foods, such as pancakes or apples, and these maintain top spots on his grocery list. Shaun is also sensitive to scents, tastes, and noises, including those neurotypicals wouldn’t notice.

These tendencies are either highlighted in episodes or used as backdrops to episode events. For instance, the pilot is titled “Burnt Toast.” It involves Shaun explaining why he needs to work at St. Bonaventure by sharing a memory that happened on a day “the air smelled like burnt toast.” A later episode has Shaun’s autism affecting his performance; the buzzing of a malfunctioning light causes a meltdown in the middle of an emergency.

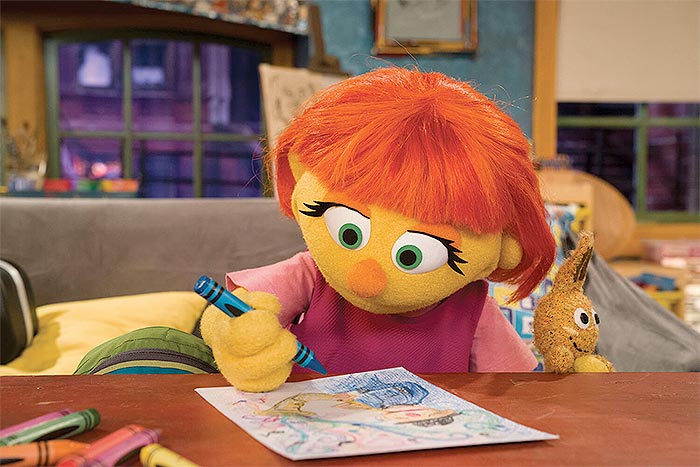

Because autism gets direct attention in The Good Doctor, viewers might expect Shaun Murphy to be a certain type of character. Namely, they might expect and dread an autistic savant, or a character whose story is built on inspiration porn (the objectification of disabled people in order to uplift the non-disabled majority or teach them lessons). Viewers might expect and dread a character who becomes so busy fighting neurotypicals’ skepticism or outright bullying, he never grows as a character. And they would have good reason for such dread. Shaun Murphy remains one of the only characters in media whose autism is directly addressed or who calls himself autistic. Characters like him tend to fall into the mold of Raymond Babbitt of Rain Man, who is defined by autism and his ability to teach his neurotypical brother Charlie to accept his cognitive differences.

Autistic And Allowed to Grow

When The Good Doctor began, it seemed another Rain Man would be born. This writer, who herself lives with cerebral palsy and Asperger’s syndrome, remembers getting tight muscles and heartburn-like sensations during “Burnt Toast” and some episodes following. In these, Drs. Andrews, Melendez, and others disparage Shaun’s skills as unimportant because he allegedly “can’t” communicate with patients. They suggest Shaun shouldn’t work at St. Bonaventure or any other hospital because doctoring involves social skills he doesn’t have, such as the ability to read nonverbal cues. Dr. Melendez, Shaun’s attending physician, assigns him to “scut work” such as cleaning up after everyone else, because he doesn’t trust Shaun to do any task other than the menial. Even after hospital president Dr. Glassman goes to bat for Shaun, the stereotyping and ableist attitudes continue. This writer remembers wondering which was worse–ableism itself, or the almost certainly hokey way Shaun would be expected to “rise above” it.

To David Shore and other writers’ credit, the opposite happens. Shaun is not coached or otherwise called upon to rise above anything or inspire anyone. He doesn’t whine or mope about his situation, and while Dr. Glassman steps in as a mentor, he does not “rescue” Shaun from ableist bullies. Instead, Shaun earns his place at St. Bonaventure through being autistic. That is, the “burnt toast” story he shares with the hospital board appears to contain irrelevant details, like the air’s smell or his pet rabbit going to Heaven. But at its core, the story is about the death of Shaun’s brother Steve and how that inspired his career path. Later on, Shaun gets reprimanded for being too blunt with patients or suggesting supposedly off-the-wall treatments. But because of Shaun’s intense visual acuity, he is able to picture the human body and how said treatments will in fact work.

Rx: Self-Acceptance, Not Shame

Shaun does occasionally work with autistic patients, or those with other disabilities. Yet he is never pigeonholed into working with them, or told he can only work with “his own kind.” If anything, Shaun is often better at working with neurotypical patients than neurodivergent ones, as seen in an episode where he meets an undiagnosed autistic man and is excoriated for suggesting an autism diagnosis. When colleagues like Drs. Brown, Lim, or even Glassman suggest making autism the main part of his story, Shaun says, “I want to be a good doctor, not a good autistic doctor.”

When autism is a major part of patient treatment or another issue, Shaun feels more confident speaking his mind. For example, in the episode mentioned above, Dr. Park basically tells Shaun, “Don’t you dare mention autism to that patient again.” Shaun holds firm, insisting the patient test himself and face the diagnosis. To Shaun, autism is not a disease, injury, or death sentence. It simply is, like brown eyes or a tenor voice. It should be addressed, in that addressing it correctly will ensure optimum understanding and care. But for Shaun, and eventually other characters, autism should be treated as normal, not an aberration.

The Good Doctor does well in showing Shaun as a fully realized autistic person in other areas, too. In four seasons, Shaun has developed a deep friendship with neighbor Lea. This has evolved into a relationship, wherein Lea and Shaun live together, and the most recent episodes reveal they’re expecting a baby girl. Said relationship experiences ups and downs, but not all the “downs” are autism-related. True, Lea has said in the past that autism means Shaun is “defective,” which turned off plenty of viewers. But since then, the couple has worked to resolve that issue and others. Recently, Shaun struggled because instead of depending on him for everything during her birth experience, Lea insisted on employing a doula. Lea has struggled because autistic or not, Shaun doesn’t always respond to what she needs or why she feels a certain way. For instance, one recent episode showed Lea negotiating with hackers who wanted to destroy St. Bonaventure’s entire grid and force them to pay an exorbitant ransom. Shaun’s major contribution to easing Lea’s stress was bringing her a sandwich.

Diagnosis: Autistic and Not Much Else

Despite these pro-autistic messages and nuanced examples, there are ways in which The Good Doctor fails to represent autism, or Shaun, well. For example, although Shaun’s relationship with Lea is well-developed, others are less so. That is, Shaun has platonic friends in Drs. Brown, Park, and others. He has a mentor in Dr. Glassman and an eventual supporter if not friend in Dr. Andrews. But these friends are also colleagues and not much else. They rarely if ever interact with Shaun outside of the hospital or a medical situation.

Those who do, such as Drs. Brown and Glassman, usually interact with Shaun on the basis of social coaching. These are the two Shaun comes to for advice on how to respond to everyone from patients to Lea to his landlord to random people who are less than understanding about autism. While it’s realistic and good for Shaun to have relationships like this, it sends the message that autistic people relate to others mostly on a “coaching” basis. If neurotypical people do not step in and help, autistic people cannot hope to understand how social mores work. Even if they practice, or do what neurotypical people say to do, autistic people are still subject to corrections or reprimands, as Shaun finds out often. Claire suggests it’s okay for Shaun to be open about his sex life; Shaun is reprimanded for talking too much or too openly about sex. Glassman suggests Shaun tell Dr. Han how he feels when the latter displays an ableist attitude. Shaun is nearly fired for the tone and words he uses.

In addition, The Good Doctor often suggests Shaun can only relate to others as an autistic person. The idea isn’t direct, but subtly present in several episodes. Shaun is not gifted the same way a neurotypical physician is. He’s gifted because of his visual abilities, which David Shore, Freddie Highmore, and others call “savant.” In other words, if Shaun were not a savant, other doctors might feel justified not only in casting aspersions, but keeping him out of the profession. In addition, the underlying message is that all the best, most worthy autistic people are savants. In reality, less than 10% of autistics are savants, which translates into less than 1% of the general population. In fact, real autistic people have expressed they’re tired of correcting this assumption. Many find it offensive.

Now You See Autism, Now You Don’t

Beyond his savant abilities, almost every aspect of Shaun’s character, as well as his story arcs, tie back into his autism. He can’t love pancakes for the sake of loving pancakes; they’re one of his “safe” or “special” foods. He can’t use the plastic scalpel Steve gave him as a touchstone. He does, but other people see it as a comfort object Shaun absolutely needs, a marker of autism and thus, atypical behavior. In an early episode, we find out Glassman doesn’t want Shaun to live by himself, but would prefer he got therapy and live-in help. Shaun puts his foot down in epic fashion, and the live-in help doesn’t happen. Viewers are meant to understand Shaun doesn’t need it. Still, he basically has to “prove” this. He also has to “prove” a person like him “deserves” to be independent even if, and perhaps because, some choices are unorthodox (e.g., sleeping on a mattress rather than in a bed at the time).

Besides these failures, David Shore himself has said The Good Doctor isn’t a representation of autism (deadline.com). In a way, this is great, because as Shore also says, the show is “a representation of Dr. Shaun Murphy.” Indeed, neither Shaun nor anyone else needs to be defined by disability, if what that means is a definition based on weaknesses. However, The Good Doctor stumbles in that it can’t decide how to represent Shaun as a whole person 100% of the time. Sometimes Shaun is a whole person, sometimes he’s autistic, and sometimes he’s a person with autism. Throw “doctor” in the mix, and the identities become more complicated because autistic people are still largely not expected to have jobs in fields like medicine. What ends up happening is, Shaun is only autistic when autism is convenient to the plot–and that’s largely when autism is treated as a disorder and gets in Shaun’s way. Otherwise, Shaun’s autism becomes anything from a cute quirk to an inconvenience.

Severe Symptoms of Fatigued Representation

Finally, well-developed as he is, Shaun Murphy still exhibits some long-standing problems with how the media represents autism. A big one is his demographic. Shaun Murphy is yet another white male autistic. Again, this is the demographic most autistics fit. But it’s more jarring with Shaun Murphy than Sherlock Holmes or Adrian Monk. In 2021, we now know female autistics exist and are a powerful part of the autism conversation. We know Black and Brown autistics exist; in fact, since several Good Doctor cast members are Black or Brown, Shaun’s whiteness can stick out like the proverbial sore thumb. We know LGBTQ+ autistics, autistics with co-occurring disabilities, and autistics from different nations or religions, exist. So with Shaun Murphy, why did the media’s powers that be fall back on the white male?

Suppose, though, Shaun Murphy was a Shauna, or non-white, or LGBTQ. Would he/she then be a better picture of “real” autism? Evidence suggests the answer is “no.” Some of that evidence goes back to Shaun’s savant traits or narrow interests, but then again, many autistics experience the latter if not the former. Some of it goes back to the tendency for the show to portray autism as getting Shaun into trouble, such as the time he was arrested. But autistic people testify, on social media and otherwise, to bullying and misunderstandings occurring throughout their lives. Some of the evidence can be found in Shaun’s monotone, stilted speech, but he’s hardly the first or only autistic person to have atypical speech patterns.

The problem is, in all these cases and others, Shaun’s autism is either overblown for drama’s sake, or underplayed as detailed above. The odd combination sends the unintentional message that autistics can “turn it on” or “turn it off.” This can lead to other faulty conclusions, such as the conclusion, “With therapy, autism will go away.” (In the campaign #actuallyautistic, hordes from the autism community have spoken out against this, and against abusive “conversion-style” therapies like Applied Behavioral Analysis, or ABA). The fact that Shaun is treated less than well when his symptoms do pop up, such as during the aforementioned meltdown, is another strike. As The Good Doctor continues into its fifth season, Shore, Highmore, and others would do well to attempt a better balance with Shaun’s character and story arcs.

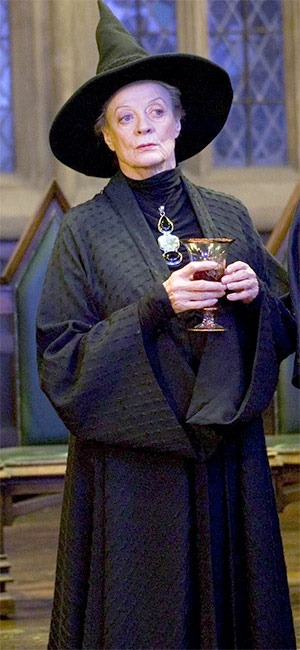

Severus Snape, Harry Potter Franchise

Severus Snape is a controversial character. His author, J.K. Rowling, once said, “Snape is morally grey. You can’t call him [a devil] and you can’t call him a saint.” Severus Snape, whose very name has roots in words that mean, “stern, unyielding” and “to snipe or bark,” commits too many sins for millions of Harry Potter fans to call him a hero or even a protagonist. Still, he does too much good to be a full-fledged villain. If we code him as autistic, his character becomes infinitely more complex. Yet, too much evidence for ASD exists for analysts to ignore the possibility.

Snape is never diagnosed with a disorder or disability. Plenty of people in the HP fandom, known as “Snaters” (Snape-haters) are eager to call him a sociopath, a Nazi, and an incel (intentional celibate). Those who are willing to admit Snape could be neurodivergent are often quick to cover that with the above negative labels. However, close analysis reveals Snape is not in fact a sociopath, and has much more going on than unhealthy obsessions or antisocial behavior. Yes, he exhibits plenty of abusive, antisocial behaviors, especially as a teacher. Excusing or whitewashing those moments would be irresponsible and unfair to his victims. Yet, neurodivergence can explain without excusing, and can net Severus Snape some much-needed depth and empathy.

Autism or a Slithering Case of Sociopathy?

It would be criminally easy to label Severus Snape a sociopath, as autistic characters sometimes are. Characters and real people like Snape are often mis-labeled because they appear to have certain characteristics that psychologist Robert Hare called sociopathic. These characteristics include “shallow affect, lack of empathy…[and] lack of guilt or remorse,” as explained by psychologist and author Maria Konnikova. 2 More than any other character we’ve studied, Severus Snape exhibits these characteristics.

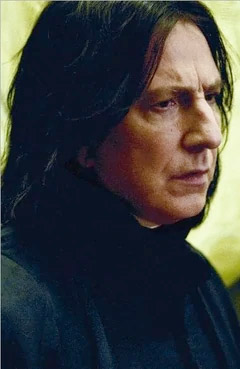

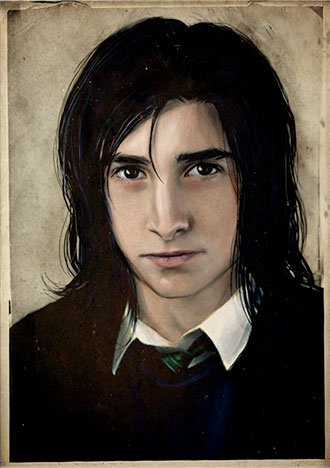

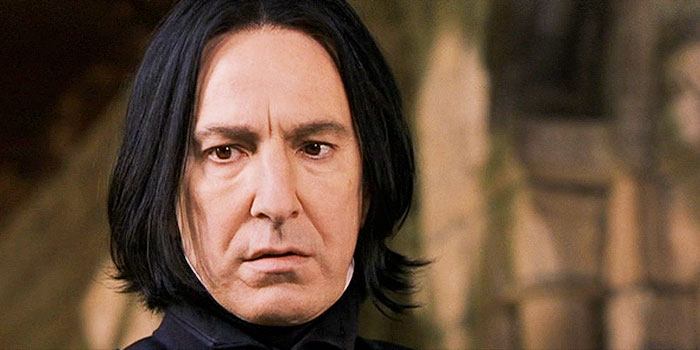

First off, Snape comes across cold as ice. His actor, Alan Rickman, described him as “[living] in very tight confines,” physically, mentally, and emotionally. This is evident in his dress–a full black cloak, plenty of buttons that remain closed up to his neck, and no color or accessories to soften the intimidation factor. Snape maintains an almost constant poker face, and although his voice can change with emotion, it mostly stays on a cultured, almost silky, even keel. In seven books and eight films, readers and viewers don’t get to see Snape smile or laugh, unless it’s sardonic. We don’t see him socialize or open up with anyone.

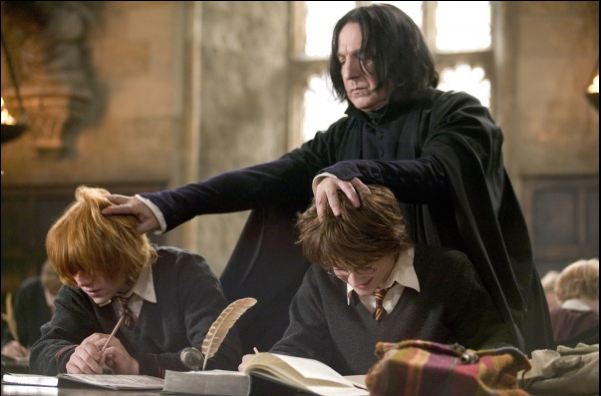

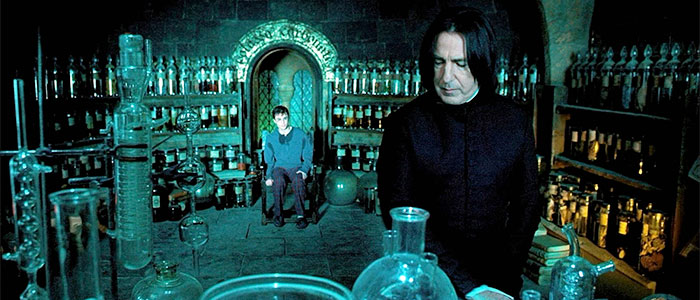

As for lack of empathy and remorse, Snape seems to personify these. Harry Potter fans despise him based on his teaching methods alone. This is a man who appears to have no problem threatening a student’s beloved pet, taking House points for minor or imagined infractions, or giving out zeroes for student mistakes he himself caused. He picks on Harry Potter mercilessly throughout the franchise, but no one else escapes his wrath. Snape embodies student Neville Longbottom’s worst fear in a Boggart. And as for his brightest and most eager student Hermione, Snape routinely ignores her and calls her “an insufferable know-it-all.” He humiliates her in front of an entire class once, when another student hits her with a jinx that elongates her teeth past her chin. The student who threw the jinx receives no consequences, possibly because they were a Slytherin, the House for which Snape is “dorm advisor” or “house parent.” Snape favors Slytherin with no remorse, and even those students aren’t entirely immune to his coldness.

Perhaps, though, Snape simply has a rough time dealing with students. Like our other characters, Snape exhibits some major gifts in his chosen fields. He’s been a potions prodigy since he was a student, eschewing textbook recipes for personal ones that were more creative and effective. Snape might prefer a Defense Against the Dark Arts (DADA) position, but he truly loves and respects potions, and will tolerate nothing less than utmost respect and care for them in his classroom. When he does get a chance to teach DADA, his passion carries over. Perhaps then, his nastiness is actually frustration based on the fact that very few students understand his gifts or personality, or how serious his fields are. Perhaps he interacts better with his colleagues.

Snape does experience frustration based on his gifts, which we’ll explore in a bit. However, his interactions with adults don’t do much if anything to save him from the easy “sociopath” label. His most infamous “colleague interaction fail” comes from Prisoner of Azkaban, when he exposes DADA Professor Remus Lupin as a werewolf, costing Lupin perhaps the only decent job he’ll ever have. If Snape is in fact autistic, this action is even worse than it appears. It means that he, a disabled person, showed absolute ableism and disrespect to someone he should’ve been allies with, who may have actually given him empathy. The fact that we almost never see Snape interacting with other colleagues, save Dumbledore, doesn’t help his case. The fact that Dumbledore is a supervisor, not a peer, actually makes the case against Snape stronger. The implication is that Snape will drum up minimal respect for authority but otherwise not relate to people as they deserve.

Sociopath or Struggling?

Before we slam the file and call Snape an unfeeling sociopath though, we should look at all these and other instances through another lens–the autistic lens. Doing so cracks Snape’s impenetrable veneer and gives readers not only another way to see him, but plenty to think about. Reading between the lines, we find Snape exhibits no characteristics of a true sociopath, but many characteristics of a coded autistic character who struggles because neuroptypicals don’t relate to him. Because of the world Snape inhabits, students and adults don’t react to him with, “I don’t always understand you, but I see and respect you,” the way that people around Sherlock Holmes, Adrian Monk, or Shaun Murphy do. Snape gets the message, “I don’t see you. I don’t understand any reason for what you’re doing. Therefore, I will treat you with contempt.”

Readers and viewers, particularly the anti-Snape crowd, often say Snape brought these reactions on himself. He willingly joined the Death Eaters. He allegedly sold out James and Harry–an infant at the time–to protect Lily, but failed because she died, too. When Snape did turn his life around, he continued in his mean-spirited, acerbic patterns, particularly in abusing children he could’ve educated and mentored. Some Snaters actually claim that, had Snape cleaned up, lightened up, and socialized more, he might’ve been a likeable person despite Death Eater history. These are all understandable, human responses to Snape’s negative behavior, but those who fully embrace them forget to look at Snape’s roots.

Beyond Behavior: Digging Up Snape’s Roots

According to occupational therapist Greg Santucci, humans cannot be categorized based on “observable behaviors” alone, 3 and nowhere is this more apparent than in the case of Severus Snape. In the Harry Potter series, we mostly observe what looks like an unfeeling man with leanings likened to the Nazi Party. We want to rail at other characters, and author J.K. Rowling, to find ways to “extinguish observable behaviors” in Snape no matter the cost–make him nicer, more open, more socially acceptable. But Snape gets more complicated if we observe his inner life, and a lifetime of behavioral triggers.

We know Severus Snape is a “half-blood,” the child of a witch mother and Muggle (non-magical) father. While half-bloods do not face as much prejudice as full Muggle-borns in the series, we can infer young Severus encountered prejudice because he wasn’t a “pureblood,” especially as he tried to make connections with pureblood students. We also know Severus came from Cokeworth, a Muggle neighborhood known for being poor and rather rough around the edges, to put it mildly. Perhaps because of Cokeworth’s hardscrabble nature, and perhaps because of pure meanness, Snape’s father Tobias was at best neglectful and at worst abusive toward his son. We don’t know how much influence Snape’s mother Eileen had in his life, but can infer she suffered under Tobias Snape’s thumb, too. No matter how much support she gave him though, Eileen died when Snape was a teenager. The teens are a crucial time to lose a parent, and if the remaining parent is absent or abusive, the loss is compounded.

“What’s Autism Got to Do With It?”

This is a fair question, and the answer is, “More than we might think.” Recall Snape’s hardscrabble childhood with the additional lens of his gifts. Rowling tells us that Snape showed gifted-level intelligence before Hogwarts, and that when he boarded the train for the first time, he was already rumored to know as much about the Dark Arts as a seventh-year. Any parent might find this intelligence intimidating, but an abusive one like Tobias Snape might outright quash it. Pair Snape’s natural gifts with an interest in the Dark Arts and an extremely introverted nature, and it’s easy to see why his personality would confuse people at best or incite abuse at worst.

Snape does try to connect with Lily, and succeeds on some level. When we meet the two as nine-year-olds, they consider each other “best friends,” which is a major social accomplishment for someone coded autistic. Young Severus makes Lily feel special and wanted, including telling her she’s special because of magic. He comforts her when her sister Petunia calls her a freak. He’s eager to strengthen the friendship, which might be why he tries to make inroads with Petunia at least once. But as far as we know, Snape has never interacted with a Muggle like Petunia, except his abuser. He doesn’t know how to relate to them except as potential threats. He ends up injuring Petunia with a fallen branch, and readers aren’t clear on whether it was accidental magic or purposeful malice. Either way, Lily’s response, “That was mean,” is a strike against Severus. When taken with his whole character and struggles, it reads less as, “Your action was mean” and more as, “You are mean.”

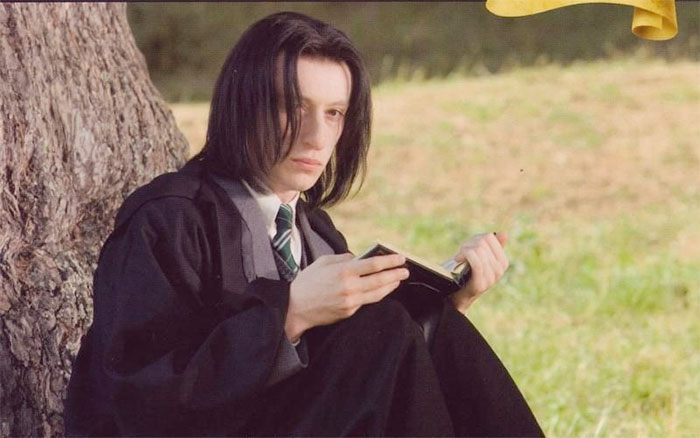

As Snape lives life at Hogwarts, he flounders more and more socially. The Sorting Hat assigns him to Slytherin and Lily to Gryffindor, meaning his only friend is not only in a different House, but the rival House. Although Severus attends Hogwarts pre-Voldemort, Slytherin is already known as the House of snobs and bullies because of founder Salazar Slytherin’s insistence on pureblood students only. The only students with whom Snape is able to connect at all are boys like Avery and Mulciber, who Rowling tells us are bullies. Snape participates in the bullying, and tells Lily it’s no big deal, which raises her ire. But the fact that he thinks bullying is no big deal, plus reads as a hanger-on to the other two, indicates he accepts bullying because he’s used to it. This behavior is normal for him.

A mountain of evidence for social floundering and autism also exists in the way Snape conducts himself outside of bullying, and is treated in general at Hogwarts. He is never seen socializing productively with anyone other than Lily, pointing back to the autistic’s habit of forming narrow, trusted social circles. The little we see of him in canon, plus headcanons and fanart, paint Snape as a brilliant and diligent student, but one with specialized interests and apparently low tolerance for anything else. (One could argue his adult assessment of non-Potions classes as containing “foolish wand-waving [and] silly incantations” is a nod to this belief). Some headcanons show Snape as proficient at Gobstones, but we don’t know if he played in canon. If he did, we don’t see him playing with other students, although we know his mother was Gobstones Club president. We can infer Snape spent more time as a player honing his skill than building friendships. Additionally, we might infer he was unusually good at Gobstones, which might’ve alienated other players.

Snape’s appearance both as a child and adult back up coding him autistic. He is described more than once as having long, black, greasy hair, and as the “greasy git of the dungeons.” Students never see him outside his signature black attire, and both headcanon and canon present him as wearing threadbare clothes during childhood. Some of this comes from socioeconomic status; kids from poor families may not have access to trendy clothing and may struggle with hygiene. But the fact that Snape maintains a “greasy,” rough around the edges, appearance into adulthood, even while making a decent salary and living in a safe place, suggests he may have sensory issues.

Snape’s signature clothing item is a cloak, a long and loose item rather than a tight or confining one. He may choose buttons over hooks, snaps, or other fasteners because they are less likely to cause unpleasant metallic sensations near the skin, or unpleasant sounds as they are fastened. As for Snape’s greasy hair, it may come from a combination of his gifts (spending all day in a potentially smelly Potions room), and sensory issues. Some autistic people dislike the sensory input of shampoo, conditioner, or water, and have to work at finding hygiene products and routines that work for them. The magical world Snape inhabits seems to have no place for autism, so perhaps he never found his routine. Failing that, his lack of hygiene could also indicate depression incurred from bullying, regretting his years as a Death Eater, losing Lily, and having to maintain such deep cover. Many autistic people experience depression at some point in their lives, and Severus Snape has a lot more triggers than most.

Autism in Snape’s Death Eater Years

Do any of Snape’s autistic characteristics explain his actions as a double agent, including the negative ones? Was autism a catalyst for some of his choices? Again, careful analysis reveals the answer is, “Yes.” Be careful to remember though, autism never excuses Snape’s actions as a Death Eater, including taking on a mantle of Voldemort’s minion at all. Autism, or any other disability, should never excuse behavior such as murder, accessory to murder, or hate crimes. To do so is to say, “Autistics are inherently dangerous and less than human because someone who acts autistic did these things.” Remember instead that autistic coding explains Snape’s actions and is meant to incite empathy and depth, not pity or carte blanche to treat people as he pleases.

Snape’s autistic coding probably had the most influence over his initial decision to follow Voldemort. By then, he was a young adult, and had gone through years of abuse at Hogwarts. We know James Potter and his friends the Marauders either bullied Snape or stood by and did nothing, “[because] he exists, if you know what I mean.” True, Snape did fight back, but the Marauders were instigators, as far back as James tripping young Severus on the train at age eleven, before the two had met. James carried his dislike of Severus so far as to perform Levicorpus on him, a spell that causes the victim to hang upside down helplessly. Once Snape was in that position, James used magic to strip him down to dirty underwear in front of a good portion of the school.

Snaters often read this incident as Snape’s “Start of Darkness” because when Lily tried to stick up for him, he called her a Mudblood. They claim Lily was right to reject her friend’s sincere apology because Mudblood is a racial slur, the use of which is taken more seriously in the 2020s than almost any decade prior. Indeed, it would be foolish of any reader, Snape supporter or not, to expect Lily to offer forgiveness, immediately or at all.

Again though, Snaters are selective in their interpretation of this incident, Snape’s Worst Memory (SWM). Many of them do not address the fact that Snape was around 15 or 16 when this happened, a time when teens are reaching sexual maturity. Thus, SWM is often read as sexual abuse, or a precursor that stopped just short of going too far. Some fans theorize Snape was stripped past underwear, but readers weren’t told because the books are still aimed at children and teens; to spell this out would’ve meant going into graphic content.

Snaters also ignore the fact that SWM came after years of abuse that no one stopped. Why no one stepped in is unclear, but recall that Snape always had an interest in the Dark Arts. That alone would’ve made him suspicious to many students. James Potter and friends took this further, deciding the existence of such a person warranted intense victimization. Like many autistics, Snape received no support in school, was branded as “weird” or unworthy of mixing with “normal” students, and was tacitly ignored when victimized. The last bit is a particular gut punch to an autistic-identifying reader like this writer. Too often in the modern school system, no matter the country, disabled students are blamed when bullied, especially when they dare stand up for themselves. Because they either have diagnoses on file or are suspected of disability, they are labeled as having “behavior problems” or “social problems.” If they react to bullying, they are seen as aggressors or told the bullying would stop if they acted more like their peers.

Severus Snape and the Complex Diagnosis

By the time Snape leaves Hogwarts, he has lost his best and only friend for good, and has his bags packed with terrible memories. In other words, he’s the perfect target for a charismatic “cult” leader like Voldemort. J.K. Rowling has noted Snape joined the Death Eaters because he was “a desperate kid,” not because he agreed with their ideals. In doing so, Snape gave in to the deep longing autistics often experience to belong somewhere, anywhere. But with no constructive options, Snape’s place to belong became another abusive group. As far as fans know, Snape only spent time doing grunt work, and Voldemort only took him seriously once–when Snape begged him to spare Lily. In fact, Snape’s failure to be taken seriously, his constant vilification at the hands of others, and his reaction to these, point to his autistic coding as a Death Eater and double agent.

Snape becomes a double agent after Lily’s death, and serves as such for 11 years before Harry Potter ever enters his life. After Harry arrives at Hogwarts, Snape seems to lean in to the negative aspects of autistic coding, becoming more acerbic and nasty than usual to protect himself. But as always with Snape, a deeper layer and deeper motives exist. By the beginning of the Harry Potter series, Snape has lost his only ally three times over–once as a friend, once to James Potter, who she chose over him as a spouse, and once to death, for good. He has turned away from the Death Eaters but received no direct, specific redemption from colleagues or understanding from students. Dumbledore comes close to expressing this, but basically treats Snape either as any other subordinate, or someone who must be monitored and coached to behave. Worse, if Snape were emotionally able to treat Harry with warmth, his double agent role would not allow it. To do so would ensure eventual certain death for one or both parties.

Like many autistics then, Snape begins suffering from a co-morbid disorder. In his case, it’s Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or C-PTSD. C-PTSD is different from its better-known counterpart, in that PTSD is usually associated with a single response to a traumatic event. The complex version is associated with “repeated trauma,” or single instances of “serious” trauma, such as “an instance of sexual abuse,” “ongoing abuse or neglect [or] witness to abuse,” or “trauma inflicted by someone you continue to have to see on a regular basis”. 4 Snape, then, checks all the boxes. He has been abused and neglected since early childhood, and certainly witnessed abuse and violence against the innocent as a Death Eater. He endured one incident of public sexual abuse that we know of, and in Prisoner of Azkaban, is forced to see and interact with a bystander to the trauma every single day.

In addition, Snape experiences a C-PTSD symptom not commonly talked about but extremely present, anger. Most people with PTSD experience anger, as well as mood swings and edginess. Again though, because of C-PTSD’s longer duration and more “severe” nature, anger like Snape’s is seated more deeply and can express itself in more severe ways. A great example occurs during Prisoner of Azkaban, when Snape tries to expose both Lupin and Sirius to the Ministry of Magic as potential dangers to Hogwarts.

In Snape’s mind, this is true not only because Lupin and Sirius might harm Harry Potter, but because they have already shown proclivity toward violence. As a teenager, Snape was almost their murder victim, when James and Sirius tried to use Lupin in werewolf form to kill him. Dumbledore either did not know about the incident or chose to sweep it under the rug. When Snape brings it up again, Dumbledore does not side with him. In fact, he agrees with the Ministry that Snape is overwrought and perhaps talking out of his mind. This does help the Golden Trio to save Sirius and Buckbeak from death, and keeps Harry’s “hero’s journey” on track. But once again, Snape, his truth, and his needs are sacrificed. The entire scene reads like a teacher or administrator deciding, once again, that a disabled student is behaving badly on purpose or has misread good intentions, as disabled people allegedly do because they can’t understand social norms. Snape’s autism and complex PTSD get another layer piled on, such that readers or viewers might wonder how or if this man can continue to function.

Severus Snape: A Portrait of Autism Undercover

Actually, Snape proves over and over he can function quite well, disorders or no, if allowed to interact in his own way. Like the other autistic characters we’ve encountered, Snape does best in his element, and finds self-acceptance where he can. If his methods are unconventional, so much the better for the people he longs to protect, especially Harry Potter and his friends.

The number of Snape’s successful “undercover operations” throughout Harry Potter are too many to list. However, it’s worth noting that autistic characteristics both help and hurt him during the series, sometimes in equal measure. A great example occurs during Harry’s first Quidditch match in Sorcerer’s Stone. In a somewhat famous scene, Harry nearly sustains serious injury when his broom begins bucking and weaving out of control. Every time the broom goes rogue, Snape’s mouth moves, causing Ron and Hermione to believe he’s the one jinxing the broom. Later on though, they learn Snape was using almost non-verbal protection spells to save Harry, and speaking in sync with Professor Quirrell, who was the real culprit. Again, Snape’s antisocial, taskmaster reputation mean he’s vilified unfairly. But his prodigy-level magic, and his choice to keep it rather secret, help Harry more than direct intervention probably ever could.

Snape continues this pattern through seven more years, sliding deeper into the double agent role. With each year, he gives up more of himself, so that gaining and maintaining a support system, friendship, or love become more unlikely. At the same time, Snape leans more into his neurodivergent side and learns to balance his intellectual prowess with as much empathy and traditional mentoring as he dares.