Bob Dylan and The Nobel: Greatest Living American Writer?

Every year, oddsmakers try to predict the notoriously fickle Nobel committee’s choice for Literature. Often, the decision is baffling, such as the obscure Chinese novelist Mo Yan winning in 2012, while other choices have been considered pleasantly surprising, such as the acclaimed Canadian short story writer Alice Munro triumphing in 2014.

In recent articles about this year’s prize, the top choice was considered Haruki Murakami, the post-modernist Japanese novelist whose work has penetrated the consciousness of Western readers in ways not seen since the day of Yukio Mishima (himself snubbed by the Nobel Committee). For U.S. readers and literary critics, the fact that a United States-born novelist has not won since Toni Morrison in 1993 is a perennial bone of contention. Philip Roth and Joyce Carol Oates, both in their 80s and rivals for the crown of the greatest (or at least most prolific) living American writer, may have thought that this year, a bizarre, confounding one full of iconic celebrity deaths and the rise of Trump, may finally bear fruit. Instead, an American even more known to the general public, and arguably as influential, won the Nobel Prize. However, despite five decades of acclaim, singer-songwriter Bob Dylan does not represent traditional “literature.”

Unlike his successor Leonard Cohen, his works of poetry were only unleashed to the public after a decade of musical works, and most people would not consider “Like a Rolling Stone” or “Just Like a Woman” poetry on the level of Walt Whitman or Emily Dickinson. The choice this year might seem odd, trendy, and pandering to audiences far from the literati, but in many ways it is deserved. The influence Bob Dylan would have, not only on subsequent musicians, but yes, decades of modernist writers, cannot be overstated. The specter of a singer-songwriter was blessedly rare before the rise of one Robert Zimmerman, but five decades on, the idea of a musician who writes, sings, and even produces his or her own work is now practically a given. By analyzing not only Dylan’s innovations but his actual, substantial output, his importance in the development of contemporary expression is undeniable, and make him a quirky but worthy fit for this monumental honor.

Popular Music and Songwriting Before Dylan-

Before Bob Dylan, arguably the three most influential and popular American musical figures were Louis Armstrong, Frank Sinatra, and Elvis Presley. The former was the original icon of jazz, known not only for his work in the Dixieland style of the ’20s, but eventually his immediately recognizable voice, which would delight audiences as late as the 1960s. Similarly, Sinatra would have a long career, ranging from his classic 1940s singles like “The Lady is a Tramp” to his late ’60s triumphs “That’s Life” and “My Way.” Despite each performer’s distinctive sound and iconic persona, neither were primarily songwriters, as their classic songs were written by a series of professional, fairly anonymous scribes. Elvis Presley arrived later on the scene in the dawn of the rock and roll era, spinning out innovative singles like “That’s All Right,” “Hound Dog” and “Heartbreak Hotel.” All of these songs, of course, were written by other people. Otis Blackwell, a struggling songwriter, notoriously added an Elvis Presley co-writing credit on “Don’t Be Cruel,” even though Elvis didn’t write a single line or contribute an iota of melody.

During the original rock boom of the 1950s, however, the nascent rise of singer-songwriters began. Buddy Holly and especially Chuck Berry delighted listeners with their charisma, guitar skill, and yes, songwriting, on such classics as “Johnny B. Goode,” “That’ll Be The Day,” “Sweet Little Sixteen” and “Not Fade Away.” These lyrics would never be mistaken for poetry, but the combination of writing and performance was innovative. Dylan himself was inspired by the tunes of Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino, and performed covers as a teenager in Hibbing, MN. Later on, however, he remarked about the simplistic nature of rock and roll compared to folk music; “the thing about rock’n’roll is that for me anyway it wasn’t enough… There were great catch-phrases and driving pulse rhythms… but the songs weren’t serious or didn’t reflect life in a realistic way. I knew that when I got into folk music, it was more of a serious type of thing. The songs are filled with more despair, more sadness, more triumph, more faith in the supernatural, much deeper feelings,” Dylan remarked in the liner notes to his 1985 box-set collection Biograph. Following the initial rise of rock and roll, a simplistic mode of music, dominated by girl-groups and Phil Spector’s immaculate wall of sound, beckoned.

Thus, in the early 1960s, rock and roll famously disappeared, as the rise of Motown and Brill Building Pop took over the industry. Both musical brands were largely producer-driven, as the musical acts simply performed the material curated by expert songwriters, such as Gerry Goffin and Carole King and Holland-Dozier-Holland. Key exceptions were Smokey Robinson (who Dylan famously called “the greatest living poet”) and later, Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder. Bubbling underneath the mainstream AM radio hits, but considerably popular at coffeehouses in Greenwich Village and Harvard Square, was the folk-boom, descended from the Depression-era innovations of Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly.

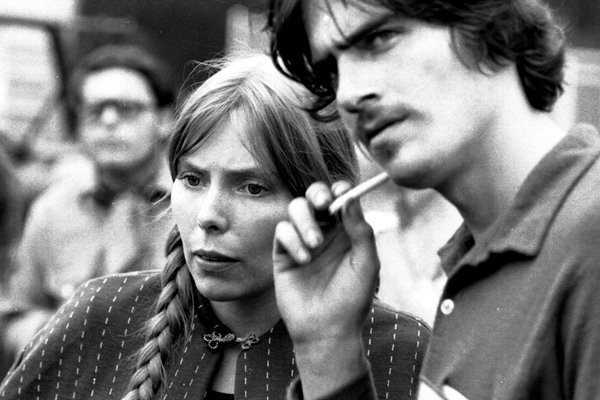

While folk music and singer-songwriters today are largely considered synonymous, it is worth remembering that at the start of the Kennedy age, the genre was a mostly interpretative movement, with traditional tunes like “He Was a Friend of Mine” sung and devoured by earnest young post-war audiences. The two early stars, The Kingston Trio and Joan Baez, Dylan’s mentor-lover, made their name with memorable renditions of pre-war traditional anthems aimed at collegiate listeners. Bob Dylan’s self-titled 1962 debut reflected this, with public-domain essentials like “House of The Rising Sun” (later a #1 Billboard hit for The Animals) and “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” dominating the track list, with only two originals on a 13-song record. Dylan’s shaky delivery and conventional choice of material would not suggest the effortlessly poetic songwriting to come. In 1963, a year when The Beatles were still singing “She loves you, yeah, yeah,” and The Rolling Stones were covering blues chestnuts like “Route 66,” Dylan unleashed an album featuring 11 original tunes, kickstarting the singer-songwriter explosion that changed the face of popular music.

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and The Rise of The Singing Poet

After the negligible sales and minor cultural exposure of Dylan’s debut, employees at Columbia Records began referring to the nasally voiced, Minnesota-born Dylan as “Hammond’s folly,” after his discovery by A&R legend John Hammond. Following the release of his follow-up, the appropriately-entitled The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, this label would melt away forever. Although the then-unpopular style of folk and Dylan’s idiosyncratic voice made sure the album would not become a Top-10 pop success, the album’s seismic, topical songs immediately became staples. “Blowin’ In The Wind,” a heartbreakingly simple and direct lament about injustice, would become a Civil Rights anthem, covered by everyone from Peter, Paul, and Mary to Stevie Wonder and influencing the immortal Civil Rights classic “A Change is Gonna Come” by Sam Cooke. When playing “Blowin’ In The Wind” to fellow R&B legend Bobby Womack, Cooke famously told his perplexed friend that “from now on, it doesn’t matter if the voice is pretty, it matters that it is telling the truth.” Dylan’s expert songwriting combined with his immediately distinctive voice would similarly influence generations of unorthodox singer-songwriters from Neil Young and Tom Waits to Joanna Newsom.

Meanwhile, his scathing anti-war protest “Masters of War” and the apocalyptic “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall” stretched the poetic boundaries for popular songwriting. Allen Ginsberg, the iconic Beat poet, famously wept when hearing the latter song’s poetic imagery and direct melodic power. Despite Dylan’s early status as a politically engaged “voice of a generation,” Dylan also impressed with the personal, tortured romantic sentiments of “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” which also became a big hit for the glossy “folkie” interpreters Peter, Paul, and Mary. The same year The Beatles sang about love on naive hits like “Please, Please Me,” John Lennon was entranced by the groundbreaking album, and within a year or two would be recording such blatant Dylan-inspired tracks as “I’m a Loser” and “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away.” By 1965, Dylan’s influence had merged the seemingly disparate folk and rock styles on such generation-defining singles as Simon & Garfunkel’s “Sound of Silence,” The Lovin Spoonful’s “Do You Believe in Magic?” and The Byrd’s “Mr. Tambourine Man,” an electric, pop-inspired cover of an acoustic Dylan demo. At the same time, Dylan’s music grew by leaps and bounds, integrating elements of rock while he incorporated surreal, modernist poetry in the vein of T.S. Eliot in his increasingly complex and enigmatic compositions.

Dylan and The Singer-Songwriter Revolution-

As aforementioned, Dylan’s songwriting led to a generation of talented singer-songwriters, as previously lightweight scribes like Lennon and Brian Wilson pushed their music to new dimensions, and Paul Simon and Gene Clark wrote influential hits like “I Am a Rock” and “Eight Miles High.” However, nobody was as innovative as Mr. Zimmerman, and in 1965 and ’66, he released three albums that represented a new high for rock music’s creative evolution, Bringing It All Back Home, Highway ’61 Revisited, and especially Blonde on Blonde, the first rock double album. Albums were previously more in the domain of jazz, as the likes of Kind of Blue and A Love Supreme proved, while rock was a decidedly singles-oriented movement. Thanks to Dylan, this all changed, and during his colossal output these two years, The Beatles’ released Rubber Soul and Revolver, The Beach Boys shocked their listeners with the symphonic glory of Pet Sounds, and The Rolling Stones threw out derivative blues pastiches on the all-originals set Aftermath. It is likely that none of this could have occurred without Dylan, but while the latter artists were still primarily musical innovators rather than literary ones, Dylan’s brilliant compositions and poetic imagery transcended the limits of pop music in a truly subversive way.

On Bringing It All Back Home, a half-electric, half-acoustic set, Dylan rambled out stream-of-conciousness to rival Joyce or Faulkner on the opening rapid-fire “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” and the penultimate “It’s Alright Ma, I’m Only Bleeding.” The closing track, the haunting, mysterious “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” combined an urgent delivery with cryptic lyrics such as “The empty handed painter from your streets

Is drawing crazy patterns on your sheets, this sky, too, is folding under you,

And it’s all over now, baby blue.” The teasingly vague lyrical content was decidedly literary, and later inspired the fiction of Joyce Carol Oates, who dedicated her short story “Where Have You Going, Where Have You Been?” (1970) to the master songwriter himself.

Dylan’s influence had largely evaded the pop charts in his original recordings, but this all changed with “Like a Rolling Stone,” a song that defined the summer of ’65, coming in second on the Billboard charts only to The Stones’ equally seminal “Satisfaction.” Combining a driving rock beat, insistent chorus, and quirky six-minute structure, the song introduced poetic devices to pop radio, and confirmed Dylan as an atypical rock star to rival the Beatles or Stones. In the fall of the same year, Dylan eviscerated the folk-music establishment in an infuriated screed of a pop song, “Positively 4th Street,” a vicious polemic that somehow became a top 10 pop hit. Anything seemed possible, and this was affirmed in Dylan’s most sprawling and creative work, 1966’s Blonde on Blonde. This album was cited by the Nobel Committee as the ideal introduction to Dylan’s literary skills and songwriting power, and indeed it is a treasure trove.

The first song, the goofy, exuberant, and lyrically simple “Rainy Day Women #12 and #35,” with its iconic “Everybody must get stoned” refrain, is a misleading start to an album with lyrics that amaze and occasionally befuddle. The first, and perhaps most complex, song to demonstrate Dylan’s knack for abstract poetry, is the sprawling, haunting “Visions of Johanna.” Such lines as “you can tell Mona Lisa had the highway blues, you can tell by the way she smiles,” and “the heat pipes just cough, the country music station plays soft, but there’s really nothing to turn off,” are leaps and bounds above the wordplay of “And Your Bird Could Sing” or “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” songs from innovative albums released the same year. These oblique, Modernist-poetry inspired lyrics seemed out of place in a rock song, but his subversive lyrical imagery galvanized his growing fanbase. Meanwhile, Dylan takes what sounds like a euphoric love song, “I Want You,” and fills it with idiosyncratic imagery. This contrasts with the churning melody and insistent, romantic chorus. It seems like a classic pop song on the surface, perhaps the purest Dylan ever wrote. Never mind that the tune begins with bizarre asides about lonesome organ grinders and guilty undertakers, and later details the misadventures of Chinese flute thieves and leaping drunken politicians.

The album closes with a 11-minute plus epic, “Sad Eyed Lady of The Lowlands,” which takes what could be a simple tribute to his wife and becomes the musical equivalent of T.S. Eliot re-writing Robert Herrick’s Julia poems. Despite its enigmatic verses and sprawling length, the song is a sincere and nakedly emotional love song (or poetic ode). On this album, which he supported with an eventful British tour, Dylan seemed unstoppable, a bona fide rock star and budding poet laureate all in one frizzy-haired, gangly persona. With a nearly fatal motorcycle accident in Upstate New York, he would go into hiding and reinvent his songwriting in a rustic vein, in a fashion shifting from Eliot to Frost.

After The Crash

The first release after his seclusion was John Wesley Harding, a musically basic, country-inflected set that turned his lyrical approach inside out. Filled with Western imagery and an outmoded, 19th century sensibility, Dylan also embedded Christian morality into tracks like “Frankie Lee and Judas Priest.” Closing with the disarmingly direct and honest “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight,” Dylan seemed to shy away from the excessive poetry and unfathomable asides of Blonde on Blonde. Despite the complexity and abundance of literary allusions found in the album’s tunes such as “The Wicked Messenger” and “Drifter’s Escape,” songs like “Dear Landlord” and “I Pity The Poor Immigrant” expressed a plainspoken directness that revealed yet another side of the multifaceted songwriter. This direct approach culminated in Nashville Skyline, a polarizing work that showcased Dylan’s sweeter, more conventional voice and lyrics with a clarity and simplicity evident by the very titles; “I Threw It All Away,” “Tonight I’ll be Staying Here With You,” “To Be Alone With You.”

No longer did Dylan fill his album with eccentric titles like “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train To Cry” or “I Shall Be Free No. 10”, but instead a lyrical approach that was emotionally devastating in its refusal to beat around the bush. Dylan’s ability to express simple emotions, complex poetic imagery, and lucidly pontificate about current events makes his writing remarkable in its scope and diversity. Never stuck on one writing style, his lyrical ability knew no limits. His output from 1963 to 1969 is a run nearly unsurpassed in literature, perhaps only equaled by William Faulkner’s streak from 1929 to 1936, starting with The Sound and The Fury and ending in 1936 Ablosom, Ablosom. It could be argued that Dylan’s work in this period was as innovative in songwriting as Faulkner’s work was groundbreaking to the development of the American novel. The wealth of his writing is also remarkable in its diversity. Dylan could write a heartbreakingly direct anti-love song as “It Ain’t Me Babe,” a lucid, stunning protest anthem like “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” or the stream-of-consciousness post-modernist puzzle that is “Gates of Eden.”

Similar to Faulkner, Dylan’s later work was more uneven, but it included many moments of brilliance in the subsequent decades. His crowning achievement as a writer following his ’60s peak was Blood On The Tracks. Although the confessional songwriter movement of the early 1970s, spearheaded by Carole King and James Taylor, Joni Mitchell and Jackson Browne, expressed the tumultuousness of relationships elegantly, it makes sense that it would take Mr. Zimmerman himself to make what is arguably the ultimate confessional songwriter album (with the possible exception of Mitchell’s Blue). This onslaught of singer-songwriters, which also included Carly Simon, Cat Stevens, and Gordon Lightfoot, is likely to not have existed without Dylan’s influence.

With the dissolution of his marriage to Sara Lowndes, Dylan’s released a searing requiem for a relationship, and the result was a peak in songwriting and a landmark to rival Freewheelin’ or Blonde on Blonde. The songs ranged from metaphorical, complexly imagined tracks such as “Lily, Rosemary, and The Jack of Hearts” and “Simple Twist of Fate” to the searing “Idiot Wind,” ending with the anguished simplicity of “Buckets of Rain.” Over the years his output became more slipshod, despite such top-notch albums as the kaleidoscopic Desire and the moody, jazzy Oh, Mercy. However, from 1997 to 2012 Dylan knocked out a winning streak of masterful late-period works, from the Grammy-winning Time Out of Mind to The Tempest. Few writers can boast that at least one truly great work appeared every decade for a total of 50 years, but Mr. Zimmerman surely can.

Although Dylan’s status as a musical innovator is clearly assured, his literary prestige was not exactly non-existent before the Nobel. Dylan admitted a variety of influences, from Dylan Thomas (who inspired his name change) to Arthur Rimbaud and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. He was previously awarded the Pulitzer Prize, which was similarly unprecedented for a musician. His awarding of the Nobel has inevitably led to widespread criticism. While advocates for the aforementioned Roth or Murakami have their legitimate gripes, it is inarguable that Dylan’s influence, not merely as a musician or a singular vocalist, but as a writer of endlessly poetic skill, has few peers in modern American culture. Others insist that the Nobel must go to an obscure writer from a remote area of the world. This ignores the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Saul Bellow, Jean-Paul Sartre (who notoriously refused to accept the award), Harold Pinter, John Steinbeck, or Doris Lessing, highly prominent Western writers (and Nobel recipients) all.

In a contemporary culture that would rather pay hundreds of dollars to see the aging Rolling Stones or Roger Waters in concert than spend $5 on a copy of To The Lighthouse, it makes sense to deride the Nobel Committee’s decision. It could also even be argued that Dylan is not necessarily the greatest modern songwriter. One could easily vouch for Young or Waits, Mitchell or (the recently departed) Cohen, the late Gil-Scott Heron, Lucinda Williams, or The Magnetic Fields’ prolific Stephin Merritt, among countless others. However, it is clear that the contemporary idea of the singer-songwriter truly started with Dylan, and despite his career’s dull stretches, he has endless songs over a lifetime to validate his status as a literary songwriter extraordinaire.

In terms of talent, influence, and lasting appeal, Robert Zimmerman truly stands alone, in the world of literature and rock music alike.

References:

Berlatsky, Noah. “Bob Dylan Isn’t Even America’s Greatest Literary Songwriter,” LitHub, 2016.

Blake, Mark. Dylan: Visions, Portraits, and Back Pages, Mojo Press, 2005.

Kornhauber, Spencer. “Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize is Not About Music” The Atlantic, 2016.

O’Sullivan, Feargus. “Dylan’s Nobel Prize Might Be The Most Swedish Thing Ever,” CityLab, 2016.

Teicher, Craig Morgan. “Why Dylan’s Lyrics Are Literature,” The New Republic, 2016.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Bob Dylan earned the Nobel and brings genuine poetry to his work. We are too close, come back in 75 years! A day will come when he will be a luminous from our time and most of us will be dust long forgotten.

I didn’t always understand his songs but I knew it was important. I’m not convinced Bob always understood how important he was at the time. To say he was just a song and dance man is like saying Einstein was pretty good at math.

Prize for literature. Lost for words. How apt.

Well done Bob! 55 years on and still causing debate. It has been a pleasure to share your life’s work, throughout my lifetime. I would call myself an ordinary person who has always loved reading and music of all kinds. You have introduced me to so many other avenues of reading and listening through your vast body of work. Thank you for making my life richer, may you stay Forever Young.

Dylan’s songs united British folk with American blues to transport a message distilled into phrases that were riveting in their clarity and which somehow slid straight into your subconscious, bypassing any attempt at evaluation, as if you had known them all your life. That, for me, is the mark of a great poet.

“Dylan’s songs united British folk with American blues” rubbish you can take the British out they may have been a few bits left over, Are you really saying that all the time those white was over there they didn’t develope anything of their own that was unique to the contradiction they face in that country. And was there same other country who had the Blues before America.

bob dylan needs no speeches, or awards

A uniquely talented individual who’s work will last for centuries.

Neither the music nor the words stand up on their own, but put together a wonderful chemistry takes place. I’m not much interested in comparisons with established poets: Dylan’s Tambourine Man creates an experience we can’t get anywhere else, and I happen to like it.

I feel like I’m the only person who ever listened to Dylan. His songs are literary, yes, but as a storyteller. He may use poetic language of course, but his genius is in telling stories.

Bob is a great song writer and poet and the award of the Nobel Prize recognises this.

I think the argument is simple. Dylan changed music for the better. It was no longer about the popular sound, but instead it was about truth. Dylan laid his truth out for everyone to hear it, and in doing so, influenced generations.

All I can say is, when I first heard Dylan it was a revelation. He was a cracked and imperfect vessel channelling something I had thought inexpressible, but which instantly resonated: “I didn’t know I knew this until he said it”; and it was felt by a generation. That’s poetry.

I’ve never quite got it with Bob Dylan, seems like a second rate poet combined with second rate music. Perhaps it’s a gateway for people who don’t read poetry as a matter of course ?

Whose parade is next on your docket, Mrs. Rain?

He didn’t even bother to show up. WTF? Unless you’re on life support or living in a Tibetan mountain retreat without internet access or phone coverage, you don’t have a decent excuse. I’d grant the award to someone who’d actually show some appreciation for it.

I love Bob Dylan and am so glad for him, I wish he had gone there to pick it up himself. He did go to the Whitehouse to accepted a Medal of Freedom from President Obama in 2012, which coming out of the 60s and civil rights and Obama being black I suppose that was more symbolic to him.

Not appreciative? You’re putting words in Dylan’s mouth. The following are words from Dylan’s mouth.

“Good evening, everyone. I extend my warmest greetings to the members of the Swedish Academy and to all of the other distinguished guests in attendance tonight.

I’m sorry I can’t be with you in person, but please know that I am most definitely with you in spirit and honored to be receiving such a prestigious prize. Being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature is something I never could have imagined or seen coming. From an early age, I’ve been familiar with and reading and absorbing the works of those who were deemed worthy of such a distinction: Kipling, Shaw, Thomas Mann, Pearl Buck, Albert Camus, Hemingway. These giants of literature whose works are taught in the schoolroom, housed in libraries around the world and spoken of in reverent tones have always made a deep impression. That I now join the names on such a list is truly beyond words.

I don’t know if these men and women ever thought of the Nobel honor for themselves, but I suppose that anyone writing a book, or a poem, or a play anywhere in the world might harbor that secret dream deep down inside. It’s probably buried so deep that they don’t even know it’s there.

If someone had ever told me that I had the slightest chance of winning the Nobel Prize, I would have to think that I’d have about the same odds as standing on the moon. In fact, during the year I was born and for a few years after, there wasn’t anyone in the world who was considered good enough to win this Nobel Prize. So, I recognize that I am in very rare company, to say the least.

I was out on the road when I received this surprising news, and it took me more than a few minutes to properly process it. I began to think about William Shakespeare, the great literary figure. I would reckon he thought of himself as a dramatist. The thought that he was writing literature couldn’t have entered his head. His words were written for the stage. Meant to be spoken not read. When he was writing Hamlet, I’m sure he was thinking about a lot of different things: “Who’re the right actors for these roles?” “How should this be staged?” “Do I really want to set this in Denmark?” His creative vision and ambitions were no doubt at the forefront of his mind, but there were also more mundane matters to consider and deal with. “Is the financing in place?” “Are there enough good seats for my patrons?” “Where am I going to get a human skull?” I would bet that the farthest thing from Shakespeare’s mind was the question “Is this literature?”

When I started writing songs as a teenager, and even as I started to achieve some renown for my abilities, my aspirations for these songs only went so far. I thought they could be heard in coffee houses or bars, maybe later in places like Carnegie Hall, the London Palladium. If I was really dreaming big, maybe I could imagine getting to make a record and then hearing my songs on the radio. That was really the big prize in my mind. Making records and hearing your songs on the radio meant that you were reaching a big audience and that you might get to keep doing what you had set out to do.

Well, I’ve been doing what I set out to do for a long time, now. I’ve made dozens of records and played thousands of concerts all around the world. But it’s my songs that are at the vital center of almost everything I do. They seemed to have found a place in the lives of many people throughout many different cultures and I’m grateful for that.

But there’s one thing I must say. As a performer I’ve played for 50,000 people and I’ve played for 50 people and I can tell you that it is harder to play for 50 people. 50,000 people have a singular persona, not so with 50. Each person has an individual, separate identity, a world unto themselves. They can perceive things more clearly. Your honesty and how it relates to the depth of your talent is tried. The fact that the Nobel committee is so small is not lost on me.

But, like Shakespeare, I too am often occupied with the pursuit of my creative endeavors and dealing with all aspects of life’s mundane matters. “Who are the best musicians for these songs?” “Am I recording in the right studio?” “Is this song in the right key?” Some things never change, even in 400 years.

Not once have I ever had the time to ask myself, “Are my songs literature?”

So, I do thank the Swedish Academy, both for taking the time to consider that very question, and, ultimately, for providing such a wonderful answer.

My best wishes to you all,

Bob Dylan”

In the sixties and seventies he was known as “the poet who changed the perception of a generation”. His music was very relevant to the Vietnam and other wars, and where I was growing up in Apartheid South Africa the censors were very aware of the power of his words and songs like, the answer is blowing in the wind were banned .We drew strength and inspiration from his words in the underground struggle against apartheid listening to his music broadcast into South Africa on LM radio from Mozambique

Thanks, Samuel Burleigh, for this insightful history, analysis, and appreciation of the great Bob Dylan. It’s enjoyable reading that makes me want to go back to some of the wonderful songs themselves….

You don’t need to like Dylan to acknowledge that in 1965 he kicked open a door and from that moment pop music no longer had to be just a catchy tune with catchy words. At a time of extraordinary generational change, artists with something to say could instantly reach an audience of millions, not hundreds. Across all musical genres, anyone with anything interesting to say in the past 50 years owes a debt of gratitude to Dylan for allowing their voice to also be heard.

I’m glad Dylan got the prize. His literature really deserves it. I’m also worried about the state of written literature and that not even the Swedish Academy is doing it any favors. Furthermore I’d prefer they give the prize to writers that are less known and less well off economically. Still, I’m glad Dylan won the prize.

Dylan’s songs engage with the great themes of literature: romantic love and loss, power and injustice, God and salvation. His songs are crammed with storytelling. He adopts innumerable moods, from evangelical fierceness to the softest tenderness. He is probably the most gifted and wittiest rhymester since Robert Browning.

The peace nobel prize and the one for literature are the odd ones out. The committee typically gets it wrong and this year they failed on the literature bit. Peace went ok it seems, they managed to find someone who actually ended a conflict.

Dylan cobbles together words that largely make little sense. Maybe they do for him. Music wise he never really developed beyond american folk music from the mid west.

All together not bad for a weird jewish kid from the middle of nowhere but that he beats Murakami or Roth is impossible to argue.

Good article about Roth on The Tablet called The Grapes of Roth by the brilliant Liel Leibowitz.

Fantastic essay on another contentious moment in the Nobel committee’s history. I applaud the perspective Burleigh takes in not directly engaging the even more contentious cultural discussion of what constitutes (high) literature in the 21st century, but pulling the reader through connections between Dylan and notable influences in literature and in music, including (I thought most interestingly) Ginsberg and Joyce Carrol Oates. Smart, thoughtful work.

“what constitutes (high) literature”

“Ma Rainey and Beethoven once unwrapped a bedroll…”

A great article about a great artist and great person.

cool

I believe that Samuel Burleigh here has done a wonderful job in taking the efforts to give us a complete picture of the man whose win caused a great deal of controversy in a really strange year! He helped me realise the true extent and greatness of the phenomenon that he was, thank you for that. Inspite of all this, I still however have this nagging thought as to whether the Nobel Prize was the right platform to honour his immense talent…

The Nobel Prize for Literature really is unpredictable, isn’t it? Great article on Bob Dylan and his literary legacy.

Bob Dylan has proven that he not only knows how to use his voice through music and lyrics, but also through the nature of writing a story.

Bob Dylan earned it. He is a righteous song writer. I understand where he is coming from.

A good essay. Dylan, however, winning the Noble Prize always seemed odd.

The producer-driven model seems to be largely the one which is used today.