Creator Bias

Media productions are collaborative efforts. Whenever works of entertainment are discussed, people will rarely ever talk about the individuals who helped create and develop those works, especially for animation. Whenever they do, it’s usually in mediums such as live action tv shows/movies, and most often only the actors and maybe the director will be mentioned. I have no qualms to this. When it comes to the creator-consumer relationship, the most a consumer can do is pay for the work and form a judgment.

However, this doesn’t make the lack of credibility any less frustrating for me. We often hear the phrase, “give credit where credit is due”. I feel it is appropriate that generally, most people would agree that if someone creates something, they should receive credit for doing so, whether referring to a field of science, literature, visual art, etc. However, when it comes to entertainment productions, this can get complicated.

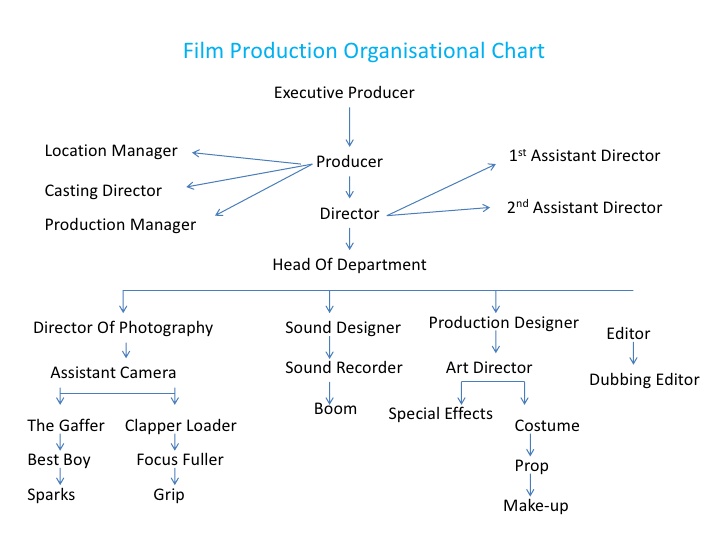

For any entertainment production, whenever the creator(s) are referred to, it is obvious that they are the ones who conceived the original idea of the finalized work. However, when it comes to film, there seems to be a misconception among many that the creators are the only people who matter regarding that work’s creation, outside of actors of course. I’m sure most are aware, at least subconsciously, that many people work on a film, as evidenced by the long rolls of credits many general audiences sit through just to get to the post-credits scenes in MCU movies.

When it comes to discussing the creatives behind movies, many conversations are reserved to the director and actors, though this isn’t to say that this is invalid. Film directors do have the most creative influence and say in how a movie is developed and executed, and certain actors attract the eye of moviegoers, whether for their celebrity status and/or performance reputation. But it’s crucial to know that they are also working with an entire crew and team, made up of multiple departments.

Screenwriters, producers, stunt coordinators, stunt doubles, visual effects artists, cinematographers, sound designers, editors, set designers, casting directors, music composers, costume and makeup artists, etc. all contribute to the production of a film. All of these are key components to creating a film, not even counting the licensing negotiations with distribution companies, and the absence of any can significantly impact a movie’s execution.

This extends to other art mediums such as novels, which go through their array of editors and publishers, comic-books (similar case though add in pencilers, inkers, colorists, letterers, publishers, etc.), and of course, animation. This lack of awareness towards other creatives and emphasis on the creator is what I like to call the “creator bias”, in which the result and execution of an art production are credited only to the creator. This can be both praise and criticism. I’ve found this bias to be somewhat damaging, as the marketing of a production being geared towards the creator can disregard others who contributed greatly to a production’s success. This is exemplified by a huge lack of knowledge concerning Mickey-Mouse co-creator, Ub Iwerks.

Ub teamed up with Walt and another animator named Les Clark to develop the earliest Mickey and Minnie Mouse drawings and did the bulk of animating, backgrounds, and designing lobber posters for theatres screening the early Mickeys. His legendary pace allowed him to handle the heavy lifting, an astounding 700 drawings per day. With Les Clark and Wilfred Jackson, Iwerks animated the third produced but first released Mickey Mouse short, Steamboat Willie (1928), and animated through the first year of Walt’s Silly Symphonies.

He left Disney in 1930 over creative differences and returned 10 years later, in which he left animation and worked with his first love of cameras and special effects. One of his first inventions at Disney was the multihead optical printer, successfully used in Song of the South and Melody Time for combining live action and animation. He developed the Xerox process of animation, which created cost-effective measures in the animation process by transferring drawings directly from an animator’s pencil on paper to cels. Ub’s innovations earned him two Academy Awards, and his cinematic contributions peaked with George Lucas’s application of optical printing in Star Wars (1977).

It was primarily thanks to Iwerks that Disney Studio reached the forefront in special photographic effects. His last work was the design of the film process for The Hall of Presidents at Walt Disney World, and in 1989 he was posthumously honored the Disney Legends award. Iwerks is considered one of the greatest animation minds of all time who made his mark in both animation and motion picture technology and helped appeal animation to a much wider audience. I’ve included all this not only to spread awareness of Iwerks’ critical role in the development and success of Disney but to highlight the effects of creator bias.

Go out on the street and ask your average joe who Walt Disney was, and they’ll likely have some idea. But ask them who Ub Iwerks was, and you’ll very likely be met with no answer, despite all his significant works to the development of Disney and animation in general, and him living a bit longer than his friend.

There are other factors for Iwerks not being well known. Most people, at least here in the U.S, generally just don’t care enough about animation as an art form, as evidenced by the stigma and condescension surrounding it. To my frustration, I’ve heard many mislabel animation as a genre rather than a medium, and that’s just a discussion for another day. But I’m aware that everyone has different interests, and different people pay attention to different things. The world holds too much information for everyone to learn, let alone bother caring to learn.

But Iwerks being overlooked may also be a consequence of his own actions. I mentioned earlier that he left Disney in 1930, in which he sold 20% of his shares in the company and returned in 1940. He had pursued forming his own studio in that decade, a deal through Pat Powers, one of the co-founders of Universal Pictures who had a complicated relationship with Walt Disney Studios. Ub’s studio folded in 1936, and by the time he returned, he’d missed Disney’s period of greatest growth in animation—innovating in color and personality animation. His decision to work in the field of motion picture rather than continue in animation may have also veered attention away from himself, as Disney is after all, primarily an animation company.

None of this is to imply Iwerks is the only overlooked Disney co-founder, let alone animation figure in general. I’m sure most people can’t really name even one of the key animators from Walt Disney’s inner circle of the Nine Old Men. If anything, it proves how the creator bias influences public perception regarding certain companies, especially one like Disney.

There are many other examples to pull from concerning creator bias. One that comes to mind is Samurai Jack, and before you chastise me, let me elaborate.

Don’t get me wrong, Genndy Tartakovsky is a brilliant animator and animation director who is a genius in his craft, and the original concept of Samurai Jack is entirely his, one that goes back all the way to even his childhood. He clearly had the most creative influence and say in the show, he wasn’t the only person who worked on it. To pull off such an ambitious masterpiece like Samurai Jack by yourself doesn’t seem possible, and it was thanks to the contributions of other great directors, storyboard artists, writers, etc. who took part in a show that we know and love today.

Besides Genndy, directors included Randy Myers, Robert Alvarez, and Rob Renzetti; writers/storyboard artists were Bryan Andrews, Charlie Bean, Aaron Springer, Darrick Bachman, Erik Wiese, Chris Mitchell, and Paul Rudish. Rudish developed the 2013 Disney Mickey Mouse shorts, and along with Tartakovsky, co-created Sym Bionic Titan with writers Bryan Andrews and Bachman. And the notorious, beautiful backgrounds that makeup SJ’s expansive world was courtesy of its art directors Dan Krall and Scott Wills.

But there is one other show that I find to suffer much more from the creator bias, one that I am much more passionate about. Avatar: The Last Airbender is single-handedly my all-time favorite tv show, and I’m sure many others share this sentiment. Just like Samurai Jack, it bares brilliant writing, directing, pacing, voice acting, art direction, East Asian cultural aspects, worldbuilding, and animation, and for me, this show is a timeless masterpiece that showcases one of the best animation can offer, especially in the West.

Quick note, I have zero first-hand knowledge of the development process of Avatar. I’m just a fan who wants to bring attention to the skilled artists who worked on the show, and I’ll be pulling from various sources and the Avatar The Last Airbender: Art of the Animated Series art book, which I highly, highly recommend to fans. It provides a huge amount of insight into how hard the crew and cast worked to bring the amazing show to life, and highlights various artists who developed specific aspects that we see in Avatar.

Discussion of Avatar is widely present to this day, but when crediting the people behind it, I hear only the creators being mentioned. I’m not trying to invalidate them. Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko were the ones who conceived the original and earliest ideas of the show, and are the reason the very concept of what Avatar is exists. Their ambitions were passionate enough to bring to Nickelodeon, where execs were convinced enough to allow them to create it.

But just like any other tv production, they worked with an entire staff of skilled writers, directors, character/prop designers, voice actors, storyboard artists, animators, and producers who wanted to tell a story they wanted to make and succeeded. Do you love Avatar’s character designs for the animals and people? You can thank primarily not only Bryan Konietzko for those, but also Angela Mueller, Jae Woo Kim, Seung-Hyun Oh, Ethan Spaulding, Jae Hong Kim, Li Hong, Aaron Alexovich, and dozens of other character designers for that. Love the show’s backgrounds? The creators conceived those concepts, specifically Konietzko for the art direction, but background designers Jevon Bue, Enzo Baldi, Ricardo F. Delgado, Jae Woo Kim, Tom Dankiewicz, and Elza Garagarza helped bring them to fruition.

The team of directors of the show are incredible too. Remember the scene in Siege of the North Part 2 where Aang and the Moon Spirit team up as “Koizilla” to defeat the Fire Nation fleet? That particular scene was storyboarded by Dave Filoni, as the episode was directed by him. Filoni later left after season 1 to become supervising director of the 2008-2015 Star Wars: The Clone Wars animated series with Giancarlo Volpe. Speaking of Volpe, he directed most of the episodes (19 episodes), with notable ones being The Avatar State, The Chase, The Drill, The Guru, Day of Black Sun Part 1, The Firebending Masters, and Sozin’s Comet Part 2: The Old Masters.

Joaquim Dos Santos joined in season 2 as a storyboard artist and later a director on season 3, in which he directed the last two parts of the Sozin’s Comet series finale. Dos Santos has also worked on many other action cartoons that are part of many people’s childhoods, being a director on Justice League Unlimited, story artist on Justice League, Spectacular Spider-Man, and Teen Titans (2003). He’s also an executive producer, director, and writer on the Netflix Voltron reboot.

Ethan Spaulding brought a unique and wild flare to the TLA crew according to the creators in the art book. He was more into anime than them, which is evidenced by his directorial work on Nightmares and Daydreams. His other notable works The Boiling Rock Part 2 and Sozin’s Comet Part 1, and was a director on The Looney Tunes Show and a co-director on Batman: Assault on Arkham.

The story of Avatar would be much different had Bryke not collaborated with these specific creatives, but especially with the writers. Bryke always wanted Zuko to be sympathetic and a villain with redemption, but it was Aaron Ehasz, head writer and co-executive producer, who “brought a softer side to the writing of Uncle’s character. “In one of our first meetings, Aaron had described Uncle as a guy who is trying to enjoy his retirement, but gets stuck watching over his nephew.” This is an exact quote from Iroh’s page in the art book. Ehasz was also the one responsible for Toph being a girl. In fact, creators Mike and Bryan originally conceived Toph as a muscular boy, and A. Ehasz had to fight with them to have her be a girl.

The place where I feel the creator bias is most present is the discrepancy between TLA and Legend of Korra. While the latter does have its fans, many Avatar fans were disappointed with it and believe it as an unworthy successor. The reasons for Korra’s criticisms have been explored and discussed many, many times among fans and non-fans all over the Internet, but not many delve into the fact that it didn’t work for the same reasons TLA did: Bryke were the only writers on Korra with full creative control.

Unlike Korra, Avatar had an entire team of great writers working with Bryke to tell the now revered story with its compelling characters. In Korra, the absence of these writers, especially the Ehaszs, was obvious, particularly with the fan service, nonsense romance, plot holes, and uninteresting and annoying characters.

A blog called The Uncommon Comma by araeph I believe has the best commentary on the writing quality between the other TLA writers and Bryke. Much of the following information comes from this source.

In it, the blogger points to the top 10 rated episodes of Avatar on IMDb with their writing credits:

Sozin’s Comet: Part 4 – Avatar Aang – Written by Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko

Sozin’s Comet: Part 3 – Into the Inferno – Written by Michael Dante DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko

The Crossroads of Destiny – Written by Aaron Ehasz

The Siege of the North: Part 2 – Written by Aaron Ehasz

Sozin’s Comet: Part 2 – The Old Masters – Written by Aaron Ehasz

Zuko Alone – Written by Elizabeth Welch Ehasz

The Avatar and the Firelord – Written by Elizabeth Welch Ehasz

The Day of Black Sun: Part 2 – The Eclipse – Written by Aaron Ehasz

The Boiling Rock: Part 2 – Written by Joshua Hamilton

The Siege of the North: Part 1 – Written by Aaron Ehasz

The Ehaszs may have written 25% of the total episodes, but they were responsible for 70% of the top rated ones.

Summarizing araeph’s points about Korra, the bending seemed to have become less impressive, no spiritual connection is required to enter the Spirit World, Korra lost all her past lives and rarely missed them, no deeper meaning is provided for bending, and many characters were rarely fleshed out to be three-dimensional at the favor of driving forward the plot. It may have been visually appealing thanks to Studio Mir’s artistic skills, but to me that further underlines the difference between Bryke and their fellow staff writers.

The other writers shared much creative control with the creators in TLA’s story. For example, Katara’s character was most often explored by the other writers, such as when she stole from pirates to improve in waterbending (The Waterbending Scroll, written by Tim Hedrick), when she discovered her healing abilities (The Deserter, written by Tim Hedrick), when she saved the Gaang in the desert (The Desert, written by Tim Hedrick), when she offered to heal Zuko’s scar, when she learned bloodbending (Tim Hedrick), when she and Toph fought over her being overbearing (The Runaway, Joshua Hamilton), when she had to overcome her anger at her father’s absence due to the war (The Awakening, Aaron Ehasz), and threatened to kill Zuko if he hurt Aang (The Western Air Temple, Elizabeth Welch Ehasz and Tim Hedrick).

Despite Bryke having written more of Aang’s screen-time heavy episodes, think of the times when Aang had to actually face his biggest challenges through overcoming his own flaws. For example, Aaron Ehaz wrote “The Storm”, in which Aang revealed running away from his role as the Avatar in the past and realized he needed to support his friends in the present. This episode also revealed Zuko’s backstory and thus had the audience truly understand his motivation, allowing us to empathize with him. He still had redeemable qualities and wasn’t willing to sacrifice his crew for the sake of his goal.

Aang demonstrating self-control and discipline that he had heretofore lacked by making it out of Koh’s lair? Written by Aaron Ehasz.

Aang fighting against his natural desire to run away and succeeding in becoming an Earthbender? Written by Aaron Ehasz.

Aang turning around after running away during the “Awakening,” realizing he can’t just abandon his friends? Written by Aaron Ehasz.

Aang pushing to keep going after the Firelord is missing from the invasion, then pushing on again even after the eclipse is over and he might die? Written by Aaron Ehasz.

Aang being questioned on how he will defeat Ozai if violence is never the answer? Written by Elizabeth Welsch Ehasz.

Aang accepting that he will have to take Ozai’s life in order to bring balance to the world? Written by Aaron Ehasz. (He also wrote Part 2 of Sozin’s Comet.)

The way I see it, Bryke are great worldbuilders. They love creating characters and worlds and designing them (and I’m sure many fantasy/sci-fi writers can relate) and plenty of their ideas have potential. But the execution of such ideas in Korra seemed lackluster. Why aren’t the Equalists heard from again after season 1? Why does opening the Spirit World portals not create a real cultural exchange between the two worlds? Why are characters like Mako, Asami, and Bolin barely fleshed out beyond generic archetypes and giving Korra romance drama?

Korra was a lost opportunity, but I didn’t find it subpar because it wasn’t ATLA. Saying things like “We should’ve gotten a sequel with the Gaang” is a sentiment I empathize with but not sympathize with, because it implies that it would’ve automatically been good just because it had the original characters (the comics disprove this in my opinion).

It implies that fictional characters/stories can somehow write themselves, but Avatar worked because it had a team of skilled, talented human beings working together for years to tell a story they wanted to see.

Korra had so much potential that I personally found it failed to live up to because Bryke went through the same ambitious process of developing Avatar without collaborating with same team of other writers who helped make it great. Even when writers Tim Hedrick and Joshua Hamilton joined them in season 2 and onward, and the two had to continue on with all the poor writing Bryke had already established.

Many people will often dismiss and ignore credits, seeing them as unimportant. I don’t fault people for not wanting to sit in front of a black screen that displays a rolling text of names they don’t know or care about, but I do find this notion a bit ironic. After all, those names are people who all contributed to the work they just watched, and if you enjoy that work, why would you not be grateful for the individuals who put forth the effort and time to create it?

I’m not saying you have to read every single credit that plays after a movie or show ends. But at least acknowledge that the shows, movies, comics, etc. you enjoy, the ones you had fun with, the ones that were your childhood, the ones which made you cry, tense, terrified, laugh, were all done by large teams of skilled and talented creatives, who all specialized in their crafts, and collaborated with each other to create something that you watched and made you walk away thinking, “Damn, that was good.”

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Indeed the making of a movie/animation is a collaborative work, its not far saying that “that film is a work of art of one person”, and, of course, saying something like “Steve McQueen’s cinematography in 12 Years A Slave was brilliant.” must come from someone who is not part of the business and/or have no knowledge whatsoever about the film making process.

The film end up being the directors view of that story. He chose the camera angles, the timing, etc.

You can give the same script to 10 different directors and you will have ten different films.

Of course the cinematographer is key in every film and the director should/must work intrinsically with the cinematographer to make reality whatever he has in his mind.

Everybody in the process deserves the same amount of credit.

Director as god was created by studios to mess writers over and keep everyone else in place. thought that was common knowledge.

I heard someone say once that if a director has done his job right he or she should be the most superfluous person on the set.

That’s right. Authorship in film is a relatively new concept.

You raise some interesting points, and I was actually just discussing earlier tonight how the emphasis on “auteurs” has failed to highlight how important and vital collaboration is to the filmmaking process. That said, it’s somewhat ironic that you focus so much on writing credits when TV writing itself is never just one person. Sure, there’s usually only one name on the episode, but that ignores that hours of group discussion and jokes that go into it, and also the fact that the showrunner often pitches the plot and/or rewrites the final episode, improving jokes, structure, tone, etc. But it was great to learn about Ub Iwerks, who illustrated your point perfectly!

You’re completely right, thank you for calling me out on that aspect. I should’ve been more fair and specified the other writers as a whole, which “Team Ehasz” was a very weak way of doing so. From what I’ve heard from writers such as Dan Harmon, Vince Gilligan, Bill Burr, etc. who write for TV, all the writers work on every episode, the credit just ends up going towards who may have been closest to that episode or was the creative lead on it. TV writing is just as much as a collaborative effort, where the writers are bouncing ideas off of each other and end doing multiple rewrites.

I do want to be clear that I believe the ATLA creators obviously contributed to the show’s writing but the other writers get overshadowed due to not having their title. Their absence in Korra seemed to at least be a part of why I found that show to be lackluster, as the creators were no longer collaborating with them to help bring in different perspectives and means of improving.

Nice article. Industry pro’s will (almost) always give credit where it is due, but the average movie-goer needs a face to place the credit. Just unfortunate human nature.

Agreed. Most average movie-goers or general audiences of media don’t care about who create/write/produce the shows or movies they watch unless it’s explicitly announced to their faces, which I always found rather strange. If you enjoyed their work, why wouldn’t you want to know who they are so you could continue supporting and following their career?

Think of it this way, when a film sucks or does crappy, you never here about the grip boy, sound mixer, writer, or even the DP being criticized.

It is what it is, of course there are alot of people that make movies what they are, the script, sound, DP, actors etc are all key components that unite a great film.

However just like a Quaterback in the NFL, when a team takes a hard loss, its usually the Quaterback or head coach who is blamed.

Great point. At the end of the day, the director oversees all the creative aspects of a film. Just as all thought work load falls on their shoulders, it’s often likewise with the reception, though it can be more nuanced in other cases as well.

John August (the guy that wrote Big Fish, The Nines, Corpse Bride and many episodes of Charlie’s Angel) will totally disagree with you about the director always getting the blame. He once stated in an article on his blog that directors tend to get most of the credit when a film is great but it is common to hear critics blaming “sloppy writing”, “weak story” or “poorly written characters” when a film fails expectations.

I totally agree. Auteur theory has been outdated for some time and people outside of the industry often have no one idea of the collaborative forces behind a production.

The answer to this is simple. Some get to much credit, some not enough. It depends entirely on the director.

Everyone should get credit / praise / blame. They are the driving force behind making an animation that works.

Yes. For example, if a director makes decisions that in the end turn out to be bad (like taking too much time in a certain scene only to have to rush other scenes to their detriment) then there is no one else to blame / credit than the director.

He is the taste behind all the decisions. Or atleast he should be. There are directors who can’t come up with anything themselves but they aren’t very good ones.

Great read. For those interested in deepening their approach to this question, many academic cultural theories often view the author as just as much of a construct as the work itself. According to these viewpoints, it is not about weather the person credited as the director wrote the script, directed, placed the lights or not. Even when someone locks himself into a room alone and writes a poem, that person never the “sole creative force” behind the poem as meaning takes place in context. See for instance: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_of_the_Author

I think what both producers and directors actually do is grossly misunderstood and under appreciated actually.

Interesting take, and I certainly don’t disagree. What specifically do you believe is misunderstood about what they do?

An enjoyable, insightful essay to read.

Thank you, glad you liked it!

breaking into the industry seems so arbitrary and/or unfair (sometimes) that it’s just better to focus on the work itself and take it as far as it goes.

Directors need to tackle this problem from the inside out and start by recognising their crews in public situations. Press interviews, awards shows etc. A worthy creative force is one which allows other creative forces around them to influence their work. Without that, you’re simply a one-dimensional projection.

The problem is that when we’re talking about Hollywood were talking about movies made for the least common denominator.

You can never really be sure what each person did. Differs in every production.

That’s a good point, unless there’s an audio commentary or behind the scenes footage, the best you can rely on are IMDB credits or panels to learn what individuals contributed to the production of a piece of media. Fortunately, social media has allowed creatives to discuss and show what they do, as especially seen from the team behind Netflix Castlevania and the Into the Spider-Verse crew. I really hope to see more transparency and behind the scenes content in media productions, especially in animation, as it can be very educational. Of course, there are the legal constraints that come with that though.

“The director” is more about marketing then the process of film making. And the cult that is generated around this phenomena in the marketing process is damaging to the process as a whole when young people approach the art with an aim to become like their idols.

This is absolutely ridiculous. If anything Acquisition and Distribution Producers take care of marketing for a film. Saying that a director is not really part of the filmmaking process isn’t just simply inaccurate, but very ignorant. Those directors who write and direct are an essential part of the film and completely deserve the credit they receive. A director must have knowledge in every aspect of filmmaking, his job is knowing everyone else’s job and communicating his vision within the context of a crew-member’s language.

There is only one director for a project, his ability to simply do the job is evidence enough that only a select few people can direct because of the immense requirements demanded and for those who excel at the career: Kubrick, Tarantino, McQueen, Boyle, Jackson, etc. These people’s very talents, skills, and personalities saturate every aspect of their films. Of course, the incredible talents of their crews is the variable of how close the film comes to their vision.

As a filmmaker, I personally couldn’t do it without a great crew and value every person on my sets. From DP to PA everybody has a job to do and no one person is more important than another. Egos can harsh the vibe. All deserve the highest respect. But if I have a crew member is poisoning the vibe on set, they’re gone. No one is irreplaceable… not even me.

The film production chart was a fine complement to the explanatory content. They clarified many vague notions about the industry.

This is very thought provoking. I feel a lot of your points are wholly accurate. You see this a great deal with music as well, where the front runner of the band gets all the credit/criticism for the whole band. I wonder if it’s just a factor of human psychology, in that we need it simple, on the whole, to just point to an individual. It’s possible that it’s literally just easier for most people to remember. I can think of dozens of films, shows, books, video games and bands where I’ve even done this – and I wait till the credits end!

Thanks for using the Avatar shows as examples.

Every A:TLA episode I point to for its writing techniques were written by one or the other Ehasz, yet I didn’t know their names. Because of this article, I’m going to find out what those writers have been up to in the past ten years.

I don’t know any crew who require public acknowledgement of the role they played. Their acclaim within the industry is what matters and, with referral being such a massive part of recruitment, that all happens internally. Which is great.

My opinion is this: It strongly depends on the director and the nature of the project. There are plenty of directors, such as Miyazaki, Tarantino, Scorsese, etc. that if you take them out of the equation the project becomes unrecognizable. Then there are projects which are completely and totally designed by committee with no real spearhead. These production are normally the giant budget blockbusters where they only need a director who makes sure the film actually gets made.

I think writer-directors have a little bit more claim to credit, but only because the seed of the film was theirs from the beginning. At the least hands on a director should be a filter through which numerous ideas enter from the other creative departments and then a select few pass through. At the most hands on a director should be spearhead, the driving force, of the creativity with no department or part of the process considered too miniscule for their attention.

That’s my opinion. But this is art. If there were a right way to do it it wouldn’t be art anymore.

Not every director is the same. Some directors have more input than others, and more responsibilities. A guy like Tarantino is more responsible for what the audience sees because he write, directs, produces and he picks his own music, settings, etc. Whereas a director hired by a studio to direct a someone else’s script that someone else is producing may not have all of creative control. So each film and director is different situations.

As a fellow avid fan of Avatar:The Last Airbender and critical analysis, this piece excites me and I love it. It’s definitely easy to apply gratitude for the final product on a few names. Being mindful of the scope of work from many unique perspectives is really important for the consumption of media. Avatar: The Last Airbender is given a lot of love from the creators and consumers alike, hence it’s quality and popularity.

A more extreme example is when moviegoers say something like “Leonardo Dicaprio’s Wolf of Wall Street”.

You notice this creator bias greatly with “auteurs,” those who get their name slapped on the title. “A Makoto Shinkai film.” “A Hideo Kojima game.” For sure, these people are likely the greatest driving forces behind these works, but to do this is to centralize the credit to one person, rhetorically erasing the work of dozens, hundreds, even thousands of others who contributed to the creation of a film or a game or other such work.

Is this a problem? Well, in one word, yes, as credit is not going where credit is due. But the age we live in is one of information bombardment from all sides. It’s tough to expect regular moviegoers or gamers to remember the dozen(s) of development leads that drive the project, much less the hundreds of others that contribute behind them. Auteurs act as marketing for a film or other work. “Empire of the Sun.” What is that? “A Steven Spielberg Film.” Ohh! I know that guy! He’s pretty good! So the movie must be good then!

While this can disproportionately prop up the most publicly well-known creators, it also pits them the public blame for a poor product. Todd Howard is the well-known director behind the Elder Scrolls and latter Fallout games, and given the positive reception of most of his studio’s output, he’s bee praised, and also meme’d for his hyperbolic tendencies on stage. However, their latest project, Fallout 76, was a failure, likely because of corporate wanting a live service-model game in a short development cycle. The game was put out in an unpolished state, indicative of a far too early release. However, this game was largely developed with help from rookie studios BGS Austin (formerly Battlecry) and BGS Dallas. The circumstances of this game’s development caused it to ultimately tank. But the other leads behind this game are shielded from public ire simply because Howard is the only well-known creative at the studio. The blame for a disastrous release is thrown squarely at him, and primarily affects his reputation, not that of the others around him. Public knowledge of yourself and subsequent reverence is a double-edged sword.

The logical question to draw from all this is to ask how this creator bias can be mitigated. What might development companies do in their industries to distribute credit in the eyes of their audience?

Completely agree with everything you said. The circumstances behind media productions are most often unexposed to the public outside of news articles, and even those don’t guarantee to spread information. It’s easier for people to pin the blame on just one face simply because they’re the face of a company or piece of media, despite it being more complicated than that.

I think the best companies can do to mitigate this bias is to be more transparent regarding their productions, whether through interviews, behind-the-scenes commentary, or allowing creatives the option to share their work on social media. The last two I think are the most effective ways, as it provides fans an inside lens of what goes on in the development stages, being both entertaining and educational. The Netflix Castlevania and Spider-Verse crews have recently been notorious for doing this on Twitter, with many of the artists/animators sharing and explaining their contributions. The same applies with Disney creatives working on the Ducktales reboot and the crew behind Rise of the TMNT on Nick, as well as art books.

Behind-the-scenes content also serves the same purpose but in a more long-form, complete set. Advertising other staff I think would help too, though I’m sure it’d have to be reserved more towards the lead creatives in certain teams and departments as there’d likely be too many people to be practical.

Had no idea Volpe and Joaquim Dos Santos worked on Avatar. It’s wild–once you learn these things and look at the content again, you see their fingerprints all over it.

As for Korra, your argument tracks in my mind. If there are fewer collaborators having voice on a project, of course the characters and plots will be more likely to have holes. More minds = better content?

Television animation is screened in very strict time windows, 7 mins, 11 mins and 22 mins are typical. Broadcasters normally spare little time to screen the credits, especially when the crew could be 100 or more folks all in different roles. Sometimes it happens at unreadable pace. I worked on some of those titles you mentioned and never expected to see credits on TV. The cinema is totally different as we all know with rolling credits that are negotiated and important and getting ever longer. Databases like IMDB are the platform to engage with details of the creatives on a project and this is pretty universally understood by people involved in production and critique of productions. IMDB used to be much like a wiki database where one could correct and add details regarding creative contribution, I have had to add myself to shows that I have worked on as producers often neglect the details and may not even know who all the subcontracted creatives have been on a show. I am not sure if that is still true. One thing is certain, that animation and the cinema arts are hugely collaborative and the network of contribution is often complex. But in my experience, people are generally generous acknowledging contributors and if one is persistent the details can be found, as you have demonstrated in this article.

This was a very enlightening article. As one who only recently watched A:TLA and Book 1 of LoK for the first time, the facts you presented make sense with regards to the differences I found between the two shows. I, for one, wanted to give LoK a chance but there were things about A:TLA that made me favour it over LoK. I also noticed you mention the popular misconception of animation as a genre rather than a medium, and I strongly believe that this is a pertinent discussion to be had. Is it something you’re working on or could it be submitted as a topic? I’d really like to see an article on that as well.

Quite a poignant article with the “great man”-ism present in many industries.