Dante and Swamp Thing’s Journey Through Purgatory

Roughly one year ago, I wrote an article about the similarities between Alan Moore’s Saga of the Swamp Thing and Dante’s Divine Comedy. Alan Moore’s work is structurally and thematically very similar to Dante’s, with the first two books of Swamp Thing mirroring Inferno, the second two Purgatorio, and the final two Paradiso. In my previous article I detailed the Inferno section of Swamp Thing. Since then, I’ve gotten numerous requests to continue my comparison. Here is Part 2.

Purgatorio is the second of Dante’s famous trilogy, detailing his journey through Purgatory. Purgatorio is often cited as the least interesting and hardest to get through of Dante’s works. In a way, this is somewhat meta, considering that Purgatory itself is supposed to be hard to get through. Unlike Inferno which is sensational and graphic, or Paradiso which is a bit surreal, Purgatorio is very much terrestrial and, to be frank, a bit boring. In order to purge themselves of sins, men are constantly working and, just as in Inferno, each action is symbolic of the sin it is purging. The penance associated with pride, for example, is to carry heavy stones around around on your back. This causes the penitant to bend over, forcing him into a humble position. The slothful are engaged in constant activity, running back and forth across the terrace. Purgatorio ends at the summit of the mountain, where an Earthly Paradise and a procession of various holy symbols awaits. Beatrice then appears and leads Dante on to Paradise.

The second act of Saga of the Swamp Thing consists of books three, four, and some of five. It aligns with Dante’s Purgatorio in that it is also a series of trials in order to purge Swamp Thing of his past sins and the moral corruption within. Swamp Thing’s guide through this stage is the character John Constantine, a sorcerer of questionable morals and an expert in exorcisms. Constantine appears after Swamp Thing is once again killed by a radioactive man who essentially poisons the plants  that make him up, depriving him of a physical body. It is at this point that Swamp Thing realizes he can grow a new body anywhere plants can grow. His consciousness survives even when his body rots away. This new body is pure, but the consciousness within needs still be purged of its past sins. Constantine tells Swamp Thing that he can theoretically regrow anywhere, using The Green as a kind of teleportation network as well. Constantine tells Swamp Thing to meet him in Rosewood, Illinois, where he must “clean up the mess [he] left behind last time.” Many of the proceeding story arcs have a similar justification. Swamp Thing returns to places he had been before Alan Moore took over the comic, and fixes the mistakes he made. He is essentially purging the past out of himself so that he may start pure in the third act. This structure is the same as Dante’s Purgatorio, in which Dante must atone for his sins before becoming worthy of being granted access to heaven.

that make him up, depriving him of a physical body. It is at this point that Swamp Thing realizes he can grow a new body anywhere plants can grow. His consciousness survives even when his body rots away. This new body is pure, but the consciousness within needs still be purged of its past sins. Constantine tells Swamp Thing that he can theoretically regrow anywhere, using The Green as a kind of teleportation network as well. Constantine tells Swamp Thing to meet him in Rosewood, Illinois, where he must “clean up the mess [he] left behind last time.” Many of the proceeding story arcs have a similar justification. Swamp Thing returns to places he had been before Alan Moore took over the comic, and fixes the mistakes he made. He is essentially purging the past out of himself so that he may start pure in the third act. This structure is the same as Dante’s Purgatorio, in which Dante must atone for his sins before becoming worthy of being granted access to heaven.

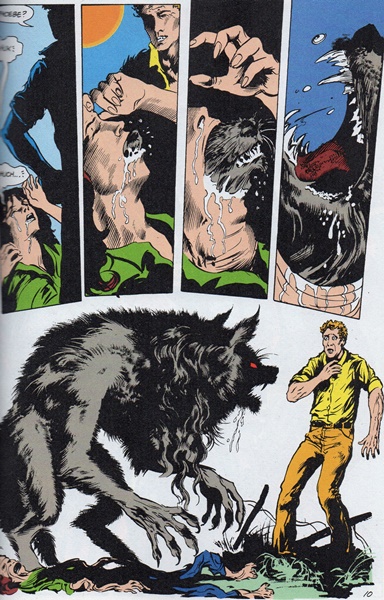

Like Dante’s Divine Comedy, in which many of the sins of the individuals are also sins of the city and political in nature, every mini-story confronts some sin not of Swamp Thing, but of American society in general. Moore criticizes many aspects of American culture in the same way Dante criticizes Florence and contemporary culture throughout his narrative. He addresses environmentalism and the danger of nuclear power in the two part arc “The Nukeface Papers,” in which a man become addicted to nuclear waste and a danger to all life around him. Moore also addresses sexism in a p ost-feminist era, by centering a werewolf narrative on a female victim of abuse and societal pressure to be perfect. Racism that still lingers after the civil rights movement when ghosts from a plantation begin to possess movie actors who share similar traits with the cruel former residents. The failed war on drugs, started by Nixon in the 1970s, is addressed when Swamp Thing produces strange tubers that give those who eat them strange hallucinogenic visions. The drug causes a dying a woman to pass on peacefully, but also causes a man to experience such fearful visions that he jumps in front of a car and dies. The action suggests that, like technology, drugs aren’t inherently good or evil, but only bring out the best or worse in a person and, if used correctly, can even beneficial to mankind. Moore even comments on religious extremists reminisce of the Westboro Baptist Church when Abby Cable receives hate mail telling her she deserves to be beat and raped because she dared fall in love with Swamp Thing. Swamp Thing isn’t merely purging himself of these human corruptions, but attempting to purge the world of them. Social and political context is key in both Saga of the Swamp Thing and The Divine Comedy, but the series can be read without knowing anything about Reagan-era America or medieval Florence. The reader understands Pope Adrian V to be an ambitiously avaricious individual without knowing the details of his reign. The important thing, for both Moore and Dante, is that the corruption and immorality are addressed in a timeless way.

ost-feminist era, by centering a werewolf narrative on a female victim of abuse and societal pressure to be perfect. Racism that still lingers after the civil rights movement when ghosts from a plantation begin to possess movie actors who share similar traits with the cruel former residents. The failed war on drugs, started by Nixon in the 1970s, is addressed when Swamp Thing produces strange tubers that give those who eat them strange hallucinogenic visions. The drug causes a dying a woman to pass on peacefully, but also causes a man to experience such fearful visions that he jumps in front of a car and dies. The action suggests that, like technology, drugs aren’t inherently good or evil, but only bring out the best or worse in a person and, if used correctly, can even beneficial to mankind. Moore even comments on religious extremists reminisce of the Westboro Baptist Church when Abby Cable receives hate mail telling her she deserves to be beat and raped because she dared fall in love with Swamp Thing. Swamp Thing isn’t merely purging himself of these human corruptions, but attempting to purge the world of them. Social and political context is key in both Saga of the Swamp Thing and The Divine Comedy, but the series can be read without knowing anything about Reagan-era America or medieval Florence. The reader understands Pope Adrian V to be an ambitiously avaricious individual without knowing the details of his reign. The important thing, for both Moore and Dante, is that the corruption and immorality are addressed in a timeless way.

Act Two of Saga of the Swamp Thing is, like Purgatorio, firmly set in the mortal world and very human in tone and feeling. Swamp Thing moves across America, defeating real monsters and outside threats, as opposed to Acts One and Three, in which the conflict is other-worldly and internal. There is also a sense of haste in both Purgatorio and Saga of the Swamp Thing. In Purgatorio, Dante must race against the sun, to reach the top before night falls. Unlike Inferno and Paradiso, which have an endless or eternal tone, Purgatorio seems to operate on mortal time. Saga of the Swamp Thing has a similar sense of rushing in Act Two, as he must hurry to defeat these evils before the crisis comes. The Act seems hurried and a lot of things happen in a very short amount of time. One issue Swamp Thing is fighting vampires in Illinois and the next he’s defeating civil war era ghosts in Louisiana. These tasks all culminate in the ultimate trial of Abby Cable in Gotham City, which operates similarly within the narrative to the pageant that takes place in the final cantos of Purgatorio.

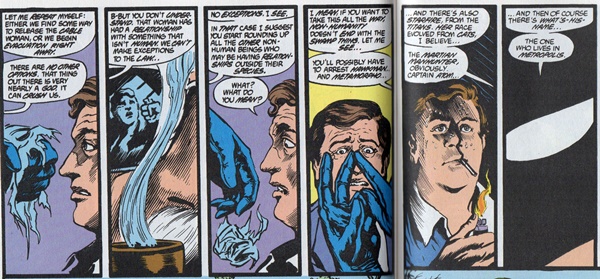

Abby is charged with having indecent relations with a non-human organism. After receiving hate mail and being the victim of this high publicity trial, she flees her small Louisiana town to Gotham City, where she is almost immediately caught, imprisoned, and put on an extradition trial. At this point Swamp Thing appears and demands his wife be released. When the people of Gotham refuse, Swamp Thing attacks the city, destroying infrastructure, attracting swarms of insects, and even going one on one with Batman himself. Gotham refuses to give into terrorism, telling Swamp Thing that she must be passed through the judicial process or all laws and rules are meaningless. As the story progresses, however, Batman begins to feel some doubt about whether it was right to arrest Abby in the first place. He asks “Perhaps Gotham should release the woman…What crime did she commit, commissioner? Who exactly did she hurt or abuse?” Later, in a confrontation with the mayor of Gotham City, the mayor claims “B-but you don’t understand. That woman has had a relationship with something that isn’t human. We can’t make exceptions to the law…” to which Batman responds:

No exceptions. I see. In that case I suggest you start rounding up all the other non-human beings who may be having relationships outside their species…I mean, if you want to take this all the way, non-human doesn’t end with Swamp Thing. Let me see…you’ll possibly have to arrest Hawkman and Metamorpho…and there’s also Starfire, from the Titans. Her race evolved from cats I believe…The Martian Manhunter, obviously. Captain Atom…And then of course there’s what’s-his-name…the one who lives in Metropolis.

He demands the mayor release Abby and the mayor acquiesces. This speech is revolutionary because it not only emphasizes the importance man places on the ability to conform, but also the bias of the law. Americans believe that justice is blind, but when faced with questions such as these the accused are judged far more harshly for what they are than what they have done.

The story arc is powerful in that it questions the judgment of man. Man finds Abby’s relationship with the Swamp Thing disgusting, and so they claim it’s illegal. Although they find no qualms with other inter-species dating, such as Superman and Lois Lane, simply because they look normal. It leads us to question the righteousness of a man-made institution such as the law in the same way Dante questioned the righteousness of the man-made and controlled church. Both Dante and Batman appeal to a higher sense of what is right than what has been dictated by man, and both Moore and Dante go to great lengths to point out the hypocrisy of these established institutions.

When Abby is released, the reunion is brief. A separate organization has found a way to, they think, kill Swamp Thing by severing his connection to The Green and destroying his body, making it impossible for him to simply grow a new one. This has several spiritual implications, especially in terms of Dante. It is ultimately your connection to God that determines whether or not you can truly die just as it is Swamp Thing’s connection to The Green that allows him to resurrect himself. This organization kills Swamp Thing because they believe he is too dangerous to their way of life, this forces Swamp Thing to retreat further than he’s ever gone, into an entirely unknown universe. As Dante purged himself of sin, Swamp Thing has purged himself of human weakness in his own trials. This death could be seen as yet another rebirth, this time into something decidedly more than human, rather than simply aspiring to human.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I often forget that Constantine started out in Swamp Thing. Anyways, I really like your article, comparing two great stories that I never really thought had much in common. Awesome work!

I think the restrictions would fall more under the question of political influence than how our species as a whole is but I still enjoyed the reading!

Might be better to look at it with political angle than our species as a whole but i still enjoyed your article!

It was good

I think you did an awesome job by comparing the two different readings. The illustrations made it even more interesting.

wow very deep

I sometimes hesitate to read books in the 80s and before because they feel dated both in art and writing. However, Swamp Thing transcends the time period.

The 80s produced some of my favorite and least favorite comics, it seems everything was either really good or just terrible.

As opposed to the 90s when everything was just awful.

I enjoyed Swamp thing and I thought the artwork was really good but I thought it was like Neil Gaimans Sandman.

Sandman was actually inspired in part by Moore’s Swamp Thing, so that’s an apt observation.

Thanks for part two. Many people believe comics are just shoot-ups, skimply-clad beauties, and aliens/robots/zombies…this is Exhibit A that that isn’t always the case. Comics – while they can be just that – are often more.

You’re welcome! I find that even when comics are “just” those things, they can still tell us a lot about our cultural values.

What a great comic!

These Swamp Thing stories are much better for people looking to enjoy lesser know classics.

Moore is an amazing author, and it at his best when he can reconstruct other people’s creations.

Lovely piece! Swamp Thing comic is legendary for its originality!

This was quite intriguing. I definitely thought this was great read.

I might end up being a very serious Swamp Thing fan by the time I’m done reading it all.

Swamp Thing is definitely one of the most intriguing characters in DC’s arsenal.

I had many copies of the Swamp Thing but it was a bit too heady for me at such a young age. Will go back to it after reading this piece, thank you!

Alan Moore knows how to write. Period.

Fantastic!

Intelligent and complex horror narrative.

I had higher hopes for Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, but I didn’t even finish it. There are interesting aspects to it (Swamp Thing is an interesting character, at least), but the horror story lines weren’t engaging to me, so I didn’t have the patience to muddle through to the occasionally good, chewy bits.

It was these Swamp Thing comics that made me a fanboy, waaaay back in 1988 when I discovered — and lost myself deep within — college comic library.

When reading ST, I was expecting heavy-handed environmentalism and a silly star-crossed lover story and was I ever wrong. I found a complex and literary storyline complete with fantastic artwork and unexpected panel-layouts ~ Just brilliant.

The artwork by Bisette and Totleben is top notch!

You’ve got to give it up to Dante for writing Purgatorio – it’s such an alien work to a contemporary reader, completely unprecedented and weird, almost like a Beckett novel but with more theology and less postmodernism – the power comes from the words on the page and the faith and history behind them rather than the narrative and images. The idea of the massive piece is its purpose.

Alan Moore writing one of the best DC characters, which he promoted to its full potential.

I remember enjoying the Swamp Thing comics much more when I was in my early teens than I enjoyed revisiting them.

Natural understanding of the flux of time.

I read this for my comic book club and we all enjoyed it!

80s anything makes me a little reluctant.

Understandable, but Swamp Thing is widely regarded as genius.

Great series. Will you do a final one on Paradiso?

I will!

You really should have had more faith in moore, because this was fantastic. a blend of monster-horror and self-discovery helps moore turn swamp thing on its head.

Swamp Thing #53 was my first introduction to Alan Moore’s writing. I hunted down all the issues of Moore’s previous Swamp Thing issues where he evolved many of the lesser known DC characters such as Etrigan The Demon, Phantom Stranger and Arcane. This series led me to try one his greatest body of work; Miracleman.