The Death of the Author: When the Pen is Mightier Than the Problematic Past

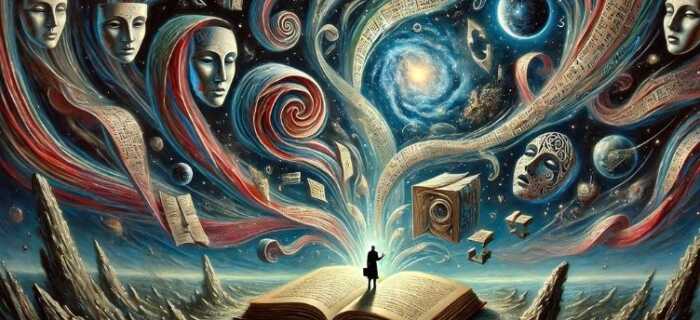

In the swirling cosmos of literature, where words dance and twist like a well-practiced tango, a curious theory emerges from the shadows: Roland Barthes’ “Death of the Author.” This idea argues that once a text is born, it exists in a universe of its own, free from the burdens of its creator’s controversial past. But as we delve into this literary graveyard, where the tombstones of J.K. Rowling and Nobuhiro Watsuki stand side by side, we must ask ourselves: is it possible to truly separate the art from the artist? Or are we simply engaging in a game of literary whack-a-mole, where problematic authors keep popping up to haunt our reading lists?

J.K. Rowling’s journey has taken her from being the beloved creator of Harry Potter to a figure stirring fierce debates, faster than a Nimbus 2000 in action. With the Harry Potter TV series on the horizon and her controversial comments continuing to spark heated discussions, fans now face a moral Quidditch match: Can they still embrace the magic of her world, or has the Divination class predicted turbulence too strong to ignore?

From Quidditch Hero to Controversy Magnet: J.K. Rowling’s Tumultuous Ride

Let’s kick things off with the elephant in the room—or should I say, the owl in the room? J.K. Rowling, the sorceress behind the Harry Potter series, has transformed from a beloved wordsmith to a lightning rod of controversy faster than a Hogwarts broomstick in flight. Her recent forays into social media have sparked debates fiercer than a Quidditch match gone wrong. While her enchanting tales have captivated millions, her comments on gender and identity have left many fans feeling as if they’ve been hit by a rogue Bludger. Can we still cheer for Harry and Hermione while side-eyeing their creator? It’s a conundrum worthy of a Divination class!

Rowling’s real-world views on transgender identity have shaken her once-loyal fanbase. The Harry Potter series, long admired for its themes of acceptance and diversity, now seems tainted for some readers, who feel a stark disconnect between the inclusive world of Hogwarts and Rowling’s controversial statements. Despite this, others argue that the magic of the Harry Potter universe is bigger than Rowling herself. With its symbols of hope and unity, the world she created stands as a cultural phenomenon, inviting us to wrestle with Barthes’ notion: can we separate the author from their work when their personal ideologies clash with the values they once wrote about?

As Rowling continues to court controversy, the wizarding world seems set to expand once more with an upcoming Harry Potter television series. HBO’s decision to reboot the series has been met with mixed reactions—some are excited for a more faithful adaptation of the books, while others are hesitant to reinvest in a franchise overshadowed by its creator’s divisive rhetoric. Can a more faithful adaptation of the beloved series revive its original magic, or will Rowling’s looming presence be impossible to shake off? The new series promises to dive deeper into the details missed in the original films, potentially reigniting love for the story while stirring the cauldron of ethical debate.

Rowling’s dilemma embodies Barthes’ key argument: once a story leaves the author’s hands, its meaning belongs to the reader. As Barthes put it, “the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.” Fans have long reinterpreted Rowling’s texts through the lenses of inclusivity and social justice, though some now wonder if that’s possible given Rowling’s increasingly vocal public opinions. Still, Barthes would insist the reader’s interpretation reigns supreme, encouraging them to untether their enjoyment of the Harry Potter universe from its problematic creator.

Yet, the complexity deepens when we realize that fans have often reimagined Rowling’s universe through fanfiction, headcanons, and reinterpretations that challenge her authorial voice. This creative rebellion might be the ultimate embodiment of Barthes’ concept, where readers essentially wield their wands to rewrite the narrative. Rowling’s growing detachment from her creation mirrors Barthes’ vision of the author fading into obscurity, leaving the work to flourish—or flounder—based solely on the interpretations and imaginations of its devoted fans.

Samurai Honor with a Side of Scandal: Can We Still Root for Kenshin?

Enter Nobuhiro Watsuki, the creator of Rurouni Kenshin (also known as Samurai X), whose fall from grace was arguably even more severe. Watsuki’s arrest for possession of child pornography sent shockwaves through the anime and manga communities. Fans of the classic samurai series were left grappling with the grim reality of his actions, struggling to reconcile the moral heroism depicted in his work with the author’s criminal behavior. Here, the dissonance between creator and creation is even sharper—how can we admire the redemptive journey of Watsuki’s protagonist, Kenshin, when the man behind the story was implicated in such a dark scandal?

Nobuhiro Watsuki’s journey from celebrated creator to disgraced criminal has left fans of Rurouni Kenshin in a moral quandary. Once the poster child for redemption and bushido, Watsuki’s arrest over child pornography drags his samurai epic through some murky waters. Fans now wonder if enjoying Kenshin’s sword-swinging adventures makes them complicit. It’s a case of art vs. artist on steroids—can we embrace the hero’s journey when the real-life creator has, let’s say, cut a little too close to the moral bone?

Watsuki’s case brings up deeper concerns. Unlike Rowling, whose controversial opinions are publicly visible and continue to evolve, Watsuki’s scandal is tied to criminality, bringing up another layer of moral reckoning for fans. The storylines of justice, honor, and personal redemption found in Rurouni Kenshin become harder to appreciate without considering Watsuki’s legal offenses. And yet, the cultural legacy of Rurouni Kenshin remains significant in anime history, much like how Harry Potter holds an immovable place in literary history. Should we continue to consume and celebrate these works, knowing the problematic behaviors of the minds behind them?

Watsuki’s case presents a stark contrast in the “death of the author” debate, pushing fans to confront more severe ethical dilemmas. While Rowling’s controversy is rooted in divisive opinions, Watsuki’s involves criminal activity, making the moral conflict even sharper. Fans of Rurouni Kenshin grapple with the weight of enjoying a work tied to such disturbing behavior. As both works evolve into larger multimedia franchises, the lines between creator and creation blur further, making it difficult to determine if we can truly separate the art from its tainted origins.

Both Rowling’s Harry Potter and Watsuki’s Rurouni Kenshin have transcended their original media—Harry Potter has evolved from a book series into a multi-billion-dollar film franchise, theme parks, and now a highly anticipated series, while Rurouni Kenshin boasts a successful manga, anime adaptation, and several live-action films. Fans have invested deeply in these stories, and their cultural impact cannot be understated. This emotional investment complicates the “death of the author” debate—when a story becomes so deeply ingrained in our collective consciousness, can we ever truly detach the creator from their creation?

The Barthesian Paradox: Judging Art in Isolation?

This brings us to Barthes’ central paradox. In his 1967 essay, The Death of the Author, Barthes advocates for the autonomy of the text. He argues that once a work is published, its meaning belongs not to the author but to the reader. According to Barthes, the author’s personal history, opinions, or even intentions are irrelevant to the interpretation of their work. The work should stand on its own. As Barthes eloquently states, “A text is made of multiple writings, drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, parody, contestation.” The author’s role becomes almost incidental in this context, as the true power of the work resides with the reader.

However, this framework is not without its critiques. Some argue that Barthes’ theory can serve as a convenient shield for problematic creators, allowing their works to remain celebrated despite their transgressions. Critics like Nancy K. Miller point out that Barthes’ approach might be too dismissive, particularly when it comes to marginalized voices. In her work Changing the Subject, Miller suggests that erasing the author’s identity can be a hegemonic tool, diminishing the importance of minority perspectives. When applied to authors like Rowling or Watsuki, does Barthes’ theory provide a post hoc justification for continuing to support their works, despite their controversial actions?

This tension between Barthes’ theory and its real-world application grows more pronounced when considering authors like Rowling and Watsuki. Can we truly dismiss their identities, especially when their personal lives contradict the values within their works? Critics argue that Barthes’ dismissal of the author may inadvertently protect creators from accountability. For marginalized voices, authorial intent can be essential in understanding the work’s impact. In cases like these, the question isn’t just about separating art from the artist—it’s about understanding how deeply entwined they truly are.

The Power of Authorial Identity: When Marginalized Voices Matter

Dismissing the author isn’t just tricky—it’s downright messy when the author’s life story shapes their art. Take Kindred by Octavia E. Butler, a mind-bending classic of time travel and systemic oppression, now a Hulu series. Butler’s own experiences as a Black woman are sewn into the fabric of every page. To declare “death of the author” here would risk cutting away the novel’s heartbeat—its personal and cultural pulse. Sometimes, the author is the magic behind the message, and erasing them? That’s a wand you don’t want to wave.

In the context of marginalized voices, the identity of the author becomes critically important. For authors from underrepresented communities, their personal experiences often shape the narratives and themes in their work, making it difficult to separate the two. Dismissing the author entirely, as Barthes suggests, can erase the social and cultural struggles that inform their writing. Works from marginalized authors are not just stories but vessels of lived experiences, and understanding their origins deepens the reader’s engagement, promoting a fuller appreciation of their significance.

As a Black woman, Butler’s personal experiences deeply influence the narrative, which explores themes of race, power, and identity. Kindred tells the story of an African American woman who time-travels to a plantation in the antebellum South, confronting the brutal realities of slavery. Butler’s own marginalized identity imbues the story with authenticity and emotional depth, making it difficult to detach the work from the author’s lived experiences. Ignoring Butler’s voice would diminish the novel’s profound exploration of systemic oppression.

The impact of Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred lies not just in its gripping narrative of time travel and the haunting legacy of slavery but also in how Butler’s voice as a Black woman defines its resonance. To apply Barthes’ “death of the author” here risks erasing the lived experience that gives Kindred its profound depth. Butler’s perspective is inextricable from the themes she explores, and dismissing it would undermine the cultural weight her work holds.

This selective application of Barthes’ theory presents a problem: invoking “death of the author” when convenient—especially to excuse problematic creators—while ignoring it when the author’s identity is key to the message, creates inconsistency. If we cannot apply the framework uniformly, then maybe the theory itself is flawed, or it requires a more nuanced approach to deciding when and how we separate the art from its creator.

Barthes’ theory can start to feel like a convenient “get-out-of-controversy-free” card when applied selectively. We can’t pick and choose when the author’s life matters—it’s all or nothing. Otherwise, we’re just playing literary hopscotch, dodging the uncomfortable parts, and landing wherever it feels safe.

Enter John Green: The Modern-Day Proponent of Barthes

In recent years, novelist John Green has openly subscribed to the “Death of the Author” philosophy. Green, known for his works like The Fault in Our Stars and Paper Towns, famously said that “authorial intent doesn’t matter.” He believes that how readers interpret a work is as important, if not more so, than what the author meant when writing it. This viewpoint opens up fascinating discussions about interpretation, particularly in books like Paper Towns, which explores themes of seeing people as more than metaphors. Green’s philosophy mirrors Barthes’ ideas but also invites deeper introspection: if authorial intent doesn’t matter, are readers free to assign any meaning to a text, even those that clash with the author’s original vision?

Green’s perspective aligns with Barthes’ in arguing for the liberation of text from the confines of the author’s mind. However, this raises interesting questions about how far this philosophy can go. In cases of problematic authors, such as Rowling and Watsuki, should we adopt Green’s stance and continue to enjoy their works purely through our interpretations? Or does supporting these creators financially and culturally imply an endorsement of their behaviors?

Consumer Responsibility and the Financial Support Dilemma

These dilemmas highlight a significant question: as consumers, where do we draw the line when it comes to separating art from the artist? Barthes argues for the liberation of the text from the author, yet fans often find themselves in the paradox of enjoying content while grappling with their creators’ moral failings. In today’s climate, this isn’t just a theoretical debate; it’s a real, messy situation that tests our fandoms and our values.

Even more complicated is the idea of supporting these creators financially. Does buying the next edition of Harry Potter or streaming the Samurai X anime make us complicit in supporting problematic behaviors? This question has led to heated discussions within fan communities, with some opting for boycotts and others choosing to compartmentalize the art from the artist.

Refusing to Fade: K-Pop Queens Who Defy the Death of the Author

But let’s get real for a second—this whole “death of the author” thing? Sure, it works when we’re talking about classic literature, where the author’s voice can be drowned in layers of symbolism and interpretation. But what happens when we step out of dusty libraries and into neon-lit K-pop stages? Suddenly, the author isn’t just alive—they’re dancing in front of us, and their involvement (or lack thereof) can make or break the connection we feel to the music.

Now, let’s talk K-pop, where this author debate takes on a whole new rhythm. In a world where some idols are hands-off with their songs, there are groups like (G)I-DLE who refuse to sit back and let someone else write their story. And believe me, that makes all the difference.

It’s funny how (G)I-DLE’s creative fingerprint is all over their music, making it impossible to ignore who’s behind the magic. Their songs aren’t just tunes—they’re personal stories, stitched together with Soyeon’s raw creativity. Meanwhile, BLACKPINK, LE SSERAFIM, and NewJeans? They’re rocking the stage, no doubt, but their music sometimes feels like a well-designed mannequin: flawless, but missing that human touch. You can vibe to it, but it doesn’t feel like you’re getting to know the artists behind the beats.

When it comes to K-pop, sometimes the author does matter. In (G)I-DLE’s case, their hands-on approach gives them this wild authenticity that sets them apart. No shade to the other groups, but when the production team is steering the ship, the connection can feel a bit… diluted. It’s like ordering fast food—it tastes good, but you know it wasn’t made just for you.

Wrapping it Up: Can We Truly Separate Art from the Artist?

In the end, perhaps the death of the author is not so much about extinguishing the light of their creations but rather illuminating the darker corners of their narratives. As we navigate this literary landscape, let’s keep our wands at the ready—because the magic of storytelling deserves to be celebrated, even when the wizards behind it leave us scratching our heads.

As we navigate the complexities of separating art from its creator, the “death of the author” doesn’t mean ignoring their influence, but it calls us to engage with the work on our terms. While authors like Rowling and Watsuki force us to reckon with personal failings, their creations often take on a life of their own, growing beyond the original intent. This intersection of art and accountability forces us to question where we draw the line between enjoying the story and confronting the shadows behind it.

Yet, can we apply Barthes’ theory without compromise? The challenge lies in the inconsistency—it becomes a balancing act between celebrating works that uplift marginalized voices and grappling with the ethical dilemmas of problematic creators. If we embrace the notion of an author’s death, we risk oversimplifying the power dynamics that shape storytelling. It’s a delicate dance, where sometimes, the identity of the creator matters as much as the creation itself.

In this intricate web of literary exploration, perhaps the true magic lies in the space between the ink and the interpretation. While we juggle problematic creators and the freedom of reader reinvention, it’s like walking a tightrope between canon and chaos. The “death of the author” gives us the freedom to rewrite, reframe, and revel in stories that outgrow their creators—but hey, maybe that’s the secret sauce. By embracing the mess, we might just unearth new layers to love, critique, or downright question.

So, grab your quills and join the conversation! The “death of the author” might just be the spark we need to breathe new life into our favorite tales, and who knows? We might even find a few hidden treasures along the way. In a world where both the creators and their creations live in shades of grey, it’s the stories that evolve through us that truly shimmer.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

There is no comparison between Rowling, who holds a default belief shared by 99.999% of all people who’ve ever lived, and Watsuki, who engages with something despicable.

I was upset when I found out about JK Rowling’s transphobia because I know that the messages she spreads hurts people I care about. Personally, I avoid continuing to benefit her financially, but I won’t get rid of the parts of the series I got before learning about her bigotry. Maybe at some point I’ll find some enjoyment in them again, but not at the moment.

I prefer to think that the JK Rowling who wrote the Harry Potter books didn’t hold the negative views she apparently has towards trans people has now. People change over time and sometimes that change isn’t always for the better. It be important to understand how and why she has grown to have these views. She has stated that she has known and even loved transgender individuals so she can’t have gone all that bad. There is usually a core issue or truth in the beliefs and views we hold even the negative ones. If we take the time to find out what these are for Rowling we might find there is indeed something there that is legitimate and needs to be addressed.

Masterpiece is a masterpiece, I dont care about what the author did.

Not until it harms you personally, or it harms someone you love.

As a wrestling fan this reminds me of the Chris Benoit situation. What he did was awful but what he did in the ring was so great. Many people revile him. Many others look past what he did to still enjoy the work he did.

Death of the Author by Barthes is a super useful lens for the discussion around “spectator/author/complicity”.

Barthes, Foucault, Burke, and, to a lesser extend, Derrida.

My personal opinion is death of the author is useful as one way to analyze the text but it’s hardly the only way. Seeking to understand the authors background and experiences and their relevance to the text is still a valid method imo.

I’ve been saying it for a while now, but Rowling is our generation’s H.P. Lovecraft. In 50 years kids are gonna pick up one of her books off the shelf, someone is gonna tell them about her views on trans people, and it’s gonna be the same “Oh shit. That’s fucked up. I get it was a different time, but like, Jesus Christ.” that people get when they learn what Lovecraft thought was an acceptable cat name.

It seems to me that the most recent decade’s worth of literary and film criticism has tended towards the opposite view expressed by Barthes; if anything there has been a decisive swing towards the cult of the author, rather than the text.

I blame reality TV.

I used to love the series before knowing about the author of Samurai X.

Still Cannot believe such an deep, meaningfull, inspirational manga was written by such an mentally ill person.

I can separate art from the artist but not the monster from the art.

Can’t separate the art from the artist when it comes to c-p.

Honestly, this is one instance where I think it’s hard to separate art from artists.

With the news of Neil Gaiman, this article is more relevant than ever.

It’s ridiculous reading this and realising Rowling has only gotten worse the past couple of years.

When a writer lets go of what she or he is writing – when she or he hits “Post comment” like I do now – the text is gone from their control (or from what feels empirically like ‘control’). The thing – a poem, novel, letter, recipe, whatever – is gone into readers’ control (or, again, what feels like ‘control’), to be made of as readers will or can or are programmed to do. (Though, of course, the writer can exert whatever post-partum control they think will enable them to shape their readers’ readings – but those efforts would be to write new things, not to determine that former from within it.) It’s not that the Author has no control, but rather that authorial control is invested in each text as it becomes present to others, as it has been let go of.

The Author as the author of some particular text has ceased ‘to live’, in the sense of authoring the text, and has now ‘died’ (let go) so that the Reader can live as a reader. ‘Literature’, then, is the process of linguistic regeneration as pieces of language travel from Author to Reader.

When it comes to what this situation with the author of Rurouni Kenshin shows which is a series famous for promoting pacifism is that pacifism doesn’t work because sometimes in life you really do need to learn how to defend yourself, which how it relates to pacifism is that pacifism actually teaches people to despise violence as much as possible which of course would get in the way of things like teaching people how to defend themselves since it would guilt trip people for not only wanting to learn how to fight but to also enjoy learning how to fight as according to pacifists fighting is something that should be despised, as well as the fact that it also teaches people that it is not okay to seek justice for something that someone did to you because according to pacifists it makes you just as bad as them if you seek justice which in this case when you look at the thing this author was involved in, this is definitely something you would need to realize that self defense would be needed for as the effect that child sexual abuse has on people is truly devastating as it truly destroys people so for that very reason the fact that he engaged in something not only so evil but definitely can justify violence being used perfectly, which goes against the priniciples his series teaches really just shows why his series is flawed as well as why pacifism shouldn’t be taken seriously as truth of the matter is there truly is real evil out there so that is why pacifism doesn’t work as it takes away your avility to learn how to protect yourself from evil.

People who can’t separate art from the artist are like people who cant separate the message from the messenger.

If you ever watched RK, you saw that is pure and free of anything related to that. Sad that people will reject the series because the author. Probs I’d do that too if I was from a newer generation. As an artist you have a responsability since you work has impacted generations, you can’t and should not become a degenerate but be a leading example.

Yeah, no. If the artist continues to make bank off their work, we have a moral obligation to boycott until they can no longer profit. The mangaka used the money he made to purchase videos. Until his pockets run dry, I cannot in good conscience support anything related to his work.

I can separate the art from the creator but he is still human garbage, the fact morons are trying so hard to defend this douchebag with “UUUUUH ITS LIKE JAPANESE CULTURE BRUH?” like that’s your way to turn his crimes around?

Hoping that this will help me come to terms with the disgusting Neil Gaiman news… take care of yourself everyone.

if the author intends their work to primarily be subject to the interpretation of the reader, that’s fine… but, if the author intended to express something complex, it’s the reader’s responsibility to make as much effort possible to understand and adhere to the author’s vision… if a reader enjoys the way other people’s words happen to coincide with what they’re already comfortable and familiar with, they’ll never be forced to see things from another point of view, i.e. a fundamental power of authorship

I wonder how Bart would’ve felt if he realized that his writings would be end up with as many different interpretations as the fiction he was talking about analyzing. I have seen the “death of the author” used by readers to explain their love of classic fiction; by filmmakers to justify completely ignoring the themes of an original work and to enforce their own world view on adaptation; and by the film industry in general to excuse reducing the input screenwriters have on a film to “somewhere below what test audiences have to say about it”. Like all theories about interpretation, it can used constructively or destructively. The goal is not to let any one theory of literature adaptation dominate your thinking to the point that you close your mind to alternate interpretations of the text.

The author is dead!

Berserk fans: 😭

Before I joined online book communities “death of the author” was super easy for me cause most of the time, unless the book was by an author who’s a household name like Rowling or King, I could read the book, love it, and gush about it to others and still not even know who wrote the book. I just never thought about the authors when I read a book and I’ve never cared to look up any particular authors, unless I was trying to find other books by them. Honestly, I’ve never understood people’s obsession with authors & other celebrities outside of the books or content/products they produce. Authors and celebrities only have influence and power because people put them on a pedestal and have decided their opinions and values are highly important and worth listening to and/or adopting. Why? Because they know how to tell an engaging story or how to act on screen? How does that make their opinions more valuable than anyone else’s? It shouldn’t, but that’s how society treats them. I just wish people would stop treating celebrities like mini-gods that have the sun shining out of their ass just cause they created something they enjoy. They’re still human with flaws that are going to fuck up sometimes and make mistakes (some much worse than others), but the sooner society can learn that the better.

Seems to me Barthes’ argument has two separate (if related) strands:- firstly, that the author is not in full control of the meaning of his text; secondly that the idea we can gain greater understanding of the text by learning about the author’s life and historical/cultural context is a mistaken one.

I suspect Barthes and his followers overstate their case. Not being in full control is not the same as being completely without control. The mutability of language does not make the meaning of a text entirely arbitrary. Certain variations are more likely than others; eg it’s unlikely that in 200 years’ time every adjective in English will mean the opposite of what it means now. There are parameters to semantic drift. Of course, one may choose to interpret a text however one likes, but there is a natural selection principle at work.

Perhaps authors are as much the drivers of semantic change as its victims. They are certainly in a stronger position than most speakers to be so.

Whilst the biographical/cultural historical approach has been overstated in the past, it is still useful. Reading Euripides or Aeschylus without explanatory footnotes on Ancient Greek culture and customs would surely render it a poorer literary experience?

I came here to try and work out how to feel about liking a series by James Kunstler after finding out a bit more about him.

If rowling were a good writer, ine might entertain her ideas of ownership.

Ahhhh Barthes. I am always pleased to see people explaining such intricate ideas making the most difficult concepts seem easy and approacheable.

How functional is a story apart from its context? A little info on era, culture, politics goes a long way. No one needs to know the author’s thoughts to know if the text works, but you need some point of reference outside of yourself. There doesn’t need to be a treatise on taking things at face value.

Oh, for the days when the most controversial thing about J. K. Rowling was her making Dumbledore suddenly gay… they were better times.

Honestly, I’ve never quite understood the need to ask authors whether something is “canon” or not or asking them to elaborate on how the story continues. For me only the text and subtext of the work in question exists and I love to see different interpretations of thar but anything beyond that is left to my imagination which kinda is the point to me. I’d hate if authors of my favourite books or movies were constantly recontextualizing the story.

As much I love Rurouni Kenshin and Makato Shishio being one of my favorite villains of all time it’s really a shame that this series will forever be remembered by a disgusting / extreme criminal behavior from the creator and the disgusting stain will be forever be in the legacy of Rurouni Kenshin

This is easily one of my favorite anime’s growing up and now I will not support it anymore.

I’m not gonna hire him as babysitter so I don’t care Kenshiin aka Samurai X is on my top 10 of greatest animation show I’ll keep watching it if there is more

I still like Rurouni Kenshin and will continue to adore it.

I recognize that some people have influence on minds of others and that my not careing about an author statement can be seen as naive but I really try not to pay attention. It is more a human thing, if someone is a dick I would not be interested in them so the whole drama with Orson Scott Card, JK and others is a problem only if those authors influence negatively other people. In that case it is valid to make a storm. And we do not give money for a personality doesnt we? So the whole situation is like one from SF, we have author writing opposite to what he things. Hitler writing Main Kapf was so predictable and easy… If he had wrote Lotr that would have been a modern complication we got used to swimm in.

Harry Potter used to be a big part of my life and Rowling’s terfery felt like a slap to the face but as time goes on, I miss it less and less. I’m not getting rid of my books but I don’t reach for them anymore. Knowing that the author wants me dead is really turning me off the books for some reason 🙄

January 2025 log : Rowling is now FULLY aware that she is actively harming trans people (women and kids especially). She is officially decreed evil.

George Lucas was a brand, yet now that Disney owns Star Wars, he couldn’t add to the canon if he wanted to. Disney has the power to sue the pants off of him if he does. It’s all about power.

Can a story be wrong? As opposed to having weak or ineffective elements such as its ending, or being perceived as having an immoral message? Or is a story simply what it is, and it’s presumed to be on purpose, so it shouldn’t change or have been different? I’ve been debating with a friend whether a certain story should have had a different ending.

Excellent work. Great topic and content.

I believe that “separating the art from the artist” is only truly possible with music. my philosophy is that if the art is directly and explicitly informed by the opinions of the artist, complete separation is impossible. maybe “opinion” isn’t the most precise word though, since in some cases the art doesn’t necessarily have to be about problematic beliefs. one example of this would be david bowie’s “blackstar.” and if you drop lyricism entirely to make instrumental music, you circumvent a entire dimension of critique. one example of this would be burzum’s “daudi baldrs.”

but I genuinely don’t know how you could do this in other mediums. worldbuilding in fictional literature will necessarily have the artist’s politics bleed through, intentionally or not. the visual aspect of film has this same problem. but I don’t read or watch movies nearly as often as I listen to music, so idk. rowling sucks ass regardless.

Barthes said “fk you! Let the reader decides your story genre”.

The author was just the name on the cover. I never felt as if I knew them, and I never wished to know them.

To me, any positive memories, associations, or even personal growth I have experienced as a result of the Harry Potter franchise is NOT in any way more important to me than the safety of trans people. I can, and have gladly chosen to, let HP go. I can’t personally separate the author from the work in this case (at least insofar as I choose to spend money on it or encourage others to do so), and I’m completely at peace with that. My special memories are worth very little when actual lives are at stake.

The art and the artist leaves as one. As the he/she, the artist is responsible for his work, whether influenced by his past or present, or whatever materials, the artist cannot be separated from his doings.