Looking at Art in Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward

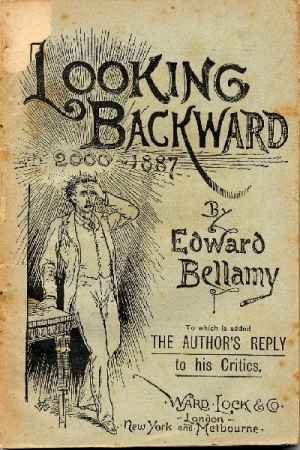

What becomes of fine art in the ideal democratic society where citizens have equal rights and equal access to wealth? Where the arbiters of taste and style are not an elite subset selected by birthright or the knack for capital accumulation but are the people en masse? Perhaps some answers to these heady and long-standing questions can be found in the Utopian society envisioned by American author Edward Bellamy. His bestselling novel, Looking Backward: 2000-1887, first published in 1888 by Houghton Mifflin, imagines just such an egalitarian society. A close reading of the book offers clues as to how Bellamy imagined the arts might develop in a culture where the many, rather than the privileged few, had access to arts education and the leisure time necessary to study, make, and enjoy it. However, before plunging into the details, it’s worth considering that both before and after Bellamy’s time observers of the American experiment have not always seen the arts and democracy as fully compatible.

What becomes of fine art in the ideal democratic society where citizens have equal rights and equal access to wealth? Where the arbiters of taste and style are not an elite subset selected by birthright or the knack for capital accumulation but are the people en masse? Perhaps some answers to these heady and long-standing questions can be found in the Utopian society envisioned by American author Edward Bellamy. His bestselling novel, Looking Backward: 2000-1887, first published in 1888 by Houghton Mifflin, imagines just such an egalitarian society. A close reading of the book offers clues as to how Bellamy imagined the arts might develop in a culture where the many, rather than the privileged few, had access to arts education and the leisure time necessary to study, make, and enjoy it. However, before plunging into the details, it’s worth considering that both before and after Bellamy’s time observers of the American experiment have not always seen the arts and democracy as fully compatible.

The Fear of Mass Taste

From the early days of the United States, cultural critics have worried that democratic notions of equality are incompatible with the ability to attain achievement within the fine arts. The chief fear (and supposition) is that the cruder tastes of the undistinguished mass will frustrate, if not entirely prevent, refined expressions of artistic subtlety and ascendant beauty. Alexis de Tocqueville, for example, supposed the absence of an aristocratic class would result in a state where, “the productions of artists are more numerous, but the merit of each production is diminished. No longer able to soar to what is great, they cultivate what is pretty and elegant, and appearance is more attended to than reality.”[1] Art would, he warned, “put the real in place of the ideal,” effectively privileging the baser senses of the body over the higher, nobler aspects of the spirit.

Time and the revelation that there was an upper, if not aristocratic, class in America have not relieved concerns that mass tastes would dilute the arts. In the famous essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” for example, art critic Clement Greenberg acknowledged the traditional necessity of a monied class to sustain the arts “by an umbilical cord of gold,” despite the fact he believed some form socialism was necessary to “the preservation of whatever living culture we have right now.”[2] Although the essay appears to indict popular culture as undermining the development of an artistic avant-garde, it is ultimately the “unwilling” attitude of the upper class to support new modes of expression that Greenberg implicates: “…today such culture is being abandoned by those to whom it actually belongs—our ruling class.” Though he suggested the lower classes did not have “enough leisure, energy and comfort to train for the enjoyment of Picasso” due to their economic subjugation, he doubted that the “peasant” possessed a “ ‘natural’ urgency” to seek out “superior culture” despite the obstacles before him. Like de Tocqueville, Greenberg criticized the masses for putting the real in place of the ideal (in this case, the style of realism in place of the emergent abstract expressionism Greenberg championed). In Greenberg’s view, the masses were like “the birds that pecked at the fruit in Zeuxis’ picture.”

Situated between de Tocqueville and Greenberg, Edward Bellamy’s answer to the question of art’s fate in a society where mass interests hold sway seems to answer the former and anticipate the latter. It is certainly a question Bellamy felt he had to address in Looking Backward. In the novel, Bellamy’s chief goal was to delineate, in an engaging manner, precisely how government, labor practices, and the means of production might be organized to ensure all citizen’s had equitable access to society’s resources. That he considered the arts as one of these resources, along with food, shelter, education, and opportunity, indicates they were held to be of some importance as an indicator of a society’s viability. Like Thomas Jefferson before him, Bellamy knew his readers, as members of the established system (capitalism in Bellamy’s case, monarchism in Jefferson’s), would judge a new form of government not only by its ability to achieve social stability but also by its ability to foster man’s higher sensibilities and expressions.

Though Bellamy devoted more ink to imagining the flowering of music and literature in the year 2000 than to what would have been considered the traditional visual arts in his day, painting and sculpture, it is the visual arts in which I am most interested and will consider here. When the protagonist Julian West awakens from his 113-year sleep, one of the first facts that Bellamy establishes about West’s strange, new environment is the presence of culture. In his first exchange with West, Dr. Leete observes, “My dear sir, your manner indicates you are a man of culture, which I am aware was by no means the matter of course in your day as it now is”(50). This statement is more than a judgment of West. It reveals that both Dr. Leete and the society of which he is a part possess, at a minimum, a refinement equivalent to the strata of late-19th century that Bellamy’s intended audience would have considered most cultured.

Envisioning the Year 2000—113 Years before the Fact

The 19th-century reader was also provided “visual” evidence of the future age’s cultivation. When West first gazes down upon the transformed cityscape of the new Boston, the presence of statues that “glistened” and fountains that “flashed” in the large open squares of every quarter indicates this society has both sufficient wealth and good taste to adorn its public spaces with art. Later in the novel, when the protagonist visits the public storehouse with Edith Leete, he notices that in place of commercial advertising there is art. The portal to the store is crowned by “a majestic life-size group of statuary, the central figure of which was a female ideal of Plenty, with her cornucopia” (92).[3] One imagines this grand work to be wrought in neo-classical style, perhaps not unlike the works of Augustus Saint Gaudens (1848-1907) and Daniel Chester French (1851-1931), who were emerging as the principal academic and leading American sculptors of Bellamy’s day when Looking Backward was being written. French, for example, had won fame in 1875 for his Minute Man, which was cast at the Ames Foundry in Chicopee, Massachusetts, at a time when Bellamy was in neighboring Chicopee Falls. So, it is not inconceivable that the author knew of this sculptor’s work. One can also see within the late 19th century a model for the novel’s emphasis upon public sculpture. After the Civil War, there was significant movement to erect public memorials in honor of fallen heroes and the coming Centennial of the nation’s birth (e.g., French’s Minute Man commissioned by the town of Concord). As one historian noted, the latter half of the 19th century was a time when statues in America began to “disappear from parlors and appear in squares and parks” in unprecedented numbers.[4] Within this movement, Bellamy may have seen an emphasis on public, as opposed to private, consumption of unique works of art that was consistent with his vision of a society where “service of the nation, patriotism, [and] passion for humanity” would replace “excessive individualism” (89, 57).

The one painting that is mentioned in the book is described as having been produced in the 19th century and resides in an art gallery, presumably a public one. It is treated as a sociological document capable of revealing ideological history, which is rather prescient on Bellamy’s part given that such readings were considered quite radical when revisionist art history was introduced in the late 20th century. This fictional painting, which is described as “representing a crowd of people in the rain, each one holding his umbrella over himself and his wife, and giving his neighbors the drippings,” may also have antecedents in the fine arts of Bellamy’s own time. Gustave Caillebotte’s “Paris Street; Rainy Day,” for example, comes to mind.

West never mentions visual arts as present within the private sphere (i.e., the Leete’s home, which serves as the reader’s model for all other private residences of this age), though he does situate music and literature within the home. One can infer, however, that like a piece of music or literature, which could be made available to many individuals simultaneously in identical form and content, if art were enjoyed privately, it too would preserve this notion of equal access. In other words, the notion of the unique work of art sequestered away in a private collection seems antithetical to Bellamy’s world. Like selfish individualism, the cult of authenticity, which segregates the arts into classes high, middlebrow, and low, seems to have been extinguished in the new age. The likelihood that reproductions rather than original works may have adorned citizen’s homes is confirmed by Dr. Leete’s description of how the society selects its art. He explains: “the people are the sole judges. They vote upon the acceptance of statues and paintings for the public buildings, and their favorable verdict carries with it the artist’s remission from other tasks to devote himself to his vocation. On copies of his work he derives the same advantage as an author on the sale of his books.”

Would Bellamy’s Utopian Society Lack An Avant-Garde?

The fact that the people, the masses, of Bellamy’s society are the ones who judge what is and isn’t art is, of course, what worried the likes of de Toqcueville and Greenberg, before and after Looking Backward. Entrusting a nation’s cultural capital to those who these observers felt lacked the discernment to favor the sublime over the sentimental, solid gold over gilt, would presumably lead to a decline in the quality of art. Bellamy takes care to establish that his “masses” have the proper credentials to serve as cultural gatekeepers. All members of society receive an equivalent basic education and, one presumes by the ubiquity of public art within the society, all have grown up with firsthand access to art and have, therefore, been able to cultivate an appreciation based on experience. In this regard, Bellamy’s fictional mass would be far better equipped that the lower classes of de Toqueville’s, Greenberg’s, or our own day to take an educated stance of the subject of art—to form an intellectual, rather than purely visceral, opinion. And, perhaps most importantly, the structure of Bellamy’s society ensures that all people have sufficient “leisure, energy and comfort” to “train” for the enjoyment of art (Greenberg 18). Whether such a society could produce grand artistic achievements or undergo a leveling, as de Tocqueville presumed, with the result that art, while never brilliant, would never truly be bad is impossible to say. Still, the novel provides a backdrop against which to imaginatively consider these questions.

Of course, the definitions of what constitutes “art” let alone “great art” are very much bound by time, place, culture, and class—even in the realm of fiction. Bellamy’s own conception of the visual arts is largely rooted in the academic tradition of the 19th century. From my vantage point, it seems his utopia would ultimately have fostered a rigidity of style and lack of innovation in the arts. To be admitted to art school, one had to show “special aptitude” since it was public policy “to encourage all to develop suspected talents which only actual tests can prove the reality of.” This indicates that one’s talent or even preferred medium of expression needed to be of a certain sort, as was common in the academy system of the late 1800s. If we accept Bellamy’s assertion that the citizens are completely content with their lot, there seems to be no breeding ground for an avant-garde dissatisfied with the status quo either in society or art. One wonders what would have become of a Romare Bearden, Andy Warhol, or Barbara Kruger in such a world.

In the end, it seems that the equal access to art that Bellamy’s imagined utopia promises is only equal when it comes to consumption. When it comes to production, or the making of what gets labeled as art in his future society, the matter of who is allowed to pursue training is regulated rather than open. There is still a specialist class appointed as gatekeepers. They decide what artistic talent is, who has it and who doesn’t, and who can pursue training. Further, there is no hint that anyone didn’t meet their criteria could work outside the system. No outsider art, here! So, while Bellamy’s vision of increased public access to art and art appreciation strikes a utopian note, his world of the future ultimately results in a restriction of artistic possibility that is decidedly dystopian.

Works Cited

[1] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Volume 2 (New York: Random House, Inc., 1990), 51.

[2] Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston, Beacon Press, 1961), 8.

[3] Of course, with its references to plenty and abundance, this statuary group does “advertise” the store in its own fashion.

[4] Michael Richman, Daniel Chester French: An American Sculptor (Washington, DC: the Preservation Press, 1983), 1.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I am very intrigued by this article, more than I was by the book. Though the ideas in the book are certainly interesting, it can become a tough read as verbose explanation often overtakes interesting storytelling.

I believe this was a very interesting book and Bellamy had a great concept with this book. Although many of Bellamy’s projections did not come true, there were some of his projections that did come true which were shocking. It is pretty scary to see how someone can be pretty accurate in telling what will take place one hundred years from now. A couple of Bellamy’s ideas that did come true included credit cards and music at any time of the day. Very cool!

Think Mr Bellamy was either the most sophomoric philosophiser to pick up a pen, or else he’d assembled a few too many model air planes. And as far as Bellamy’s attempt to visually describe the promised land, let us just say he was no Jules Verne, and let it go at that.

I believe that Bellamy’s was a horrible book and Bellamy had a disgusting concept with his book. Although none of the socialist Bellamy’s utopian projections came true, there were some of his projections that did come true which were shocking. Bellamy influenced the worst murderers of all time: the socialists Stalin, Mao, and Hitler and their ilk (see the work of the historian Dr. Rex Curry). It is pretty scary to see how someone can cause so much harm in telling what will take place one hundred years from now. Another couple of Bellamy’s ideas that were not Bellamy’s were credit cards and music at any time of the day. Bellamy touted a ration card (completely different from a credit card) but completely consistent with the poverty and misery that Bellamy inspired under the socialists Stalin, Mao and Hitler. Mr Bellamy was a sophomoric philosopher, and really should not be called a philosopher at all.

My biggest criticism about LB was that the plot barely moved, and easily have been as thorough using a third of the pages.

Wish I would have come across this articles a few weeks back during my English module when exploring Looking Backward. It certainly can open up forum for discussion and reform today without totally shattering beliefs.

Wow great article! One of the main reasons I enjoyed the original book is that there was little to no conflict. In pretty much all books I read, there is a definite problem that hassles the character. I found this as a nice release from that cliche.