Lessons from Our Favorite and Least Favorite Fictional Teachers

Besides parents or guardians, teachers are the first adults we encounter who help shape our lives, psyches, and philosophies. Every teacher we have from the time we’re small makes some impression for good or ill. Good teachers inspire and motivate us, spurring us on to follow our dreams, do well, and be kind to our fellow humans. Bad teachers leave wounds of all kinds behind, but they show us how not to interact with our world. They teach us who we do not want to become. Even a teacher who falls somewhere in between – someone who is “just okay,” or who has a balanced mixture of good and bad traits – has lessons to impart. The key lies in taking lessons from all three teacher types and deciding for ourselves when, if, and how to use them.

Teachers in the media offer lessons as valuable, if not more so, than those of our real-life teachers. As in real life, most fictional teachers fall into one of three categories – the Good, the Bad, and the In-Between. The Good ones often come across as saints, while the Bad are over-the-top antagonists and the In-Between are sometimes uncomfortably human. Whether these portrayals are fair to real-life teachers is a highly debatable question. What is not in debate, however, is how well these fictional teachers do their jobs. After “going to school” with one of these educators, we in the audience remember what they taught us for years, perhaps decades.

For the purpose of our discussion, “teacher” does not just mean “traditional classroom teacher.” A teacher can also be a principal, administrator, elective instructor (of art, music, or a similar subject), or a coach. A teacher may also fill more than one of these roles at once. He or she may be entirely fictional, or the fictionalized version of a real person who once taught or is still teaching. The teacher’s impact lies not so much in his or her title or role as in how he or she interacts with and influences students.

The Good

Some teachers are just plain good. They are not perfect saints – they are still human. Yet as educators, they are hard to beat. These are the teachers who impact students’ lives long after class ends, who put their students first, and whose impacts are felt in and outside the classroom. Truly, one hundred percent Good teachers are difficult to find even in fiction, but our favorite books and films have given us some noteworthy ones. Let’s examine just three of the best.

Miss Jennifer Honey, Matilda

The first teacher we usually encounter is our kindergarten teacher. He or she is often the one who gives us our first impression of school, who nurtures us and helps us feel secure in what may be our first environment away from our parents or guardians. Thus, ideal kindergarten teachers are often seen as warm, compassionate, and motherly. They need not be women, although most of the media’s kindergarten teachers are younger women in their early twenties to early thirties. These women are often single, perhaps to illustrate what wonderful mothers they would be if they had children of their own. More than any other Good teacher type in our discussion, the female kindergarten teacher is portrayed as a saint.

Miss Jennifer Honey of Roald Dahl’s novel Matilda seems to fit this mold. The 1996 movie based on Matilda shows her as a single woman, no older than about 25. She is soft-spoken, usually wears flowing dresses or skirts, and shows tireless dedication to her students. However, Miss Honey has a quiet but present inner strength that sets her apart from the stereotypical kindergarten teacher and makes her stand out among Good teachers. At first blush, Miss Honey looks like a shrinking violet. She seems terrified of flouting Crunchem Hall’s system, raising her voice, or breaking the rules. Readers and viewers know she has a good reason for that; Miss Honey’s principal, Agatha Trunchbull, is a tyrant for whom “sadistic” is a polite descriptor. Any flouting she does is extremely subversive. For example, Miss Honey allows Amanda Thripp to wear pigtails in class, but when Miss Trunchbull comes in to teach a lesson, she hurriedly takes Amanda’s hair down. She also hides the bright, creative ambience of her classroom behind austere lists of rules and gray cover-ups.

However, when Miss Honey encounters a student who needs her more than usual, she is willing and able to take calculated risks. When Miss Honey first meets Matilda Wormwood, she assumes the little girl is like any other student – new to school, perhaps a little nervous, and perhaps behind in the material. While Miss Honey’s first assumptions were correct, she’s floored to find Matilda is a prodigy. Matilda can already do advanced multiplication in her head and has made significant inroads in the Western literary canon. Her favorite author, she says, is Charles Dickens. Miss Honey immediately knows this little girl will not be stimulated or happy in a kindergarten classroom where, as Dahl puts it, the students spend their time “learning to spell cat and rat and mouse.” So Jennifer Honey does what she would otherwise not dare. She goes to Ms. Trunchbull’s office – where she nearly gets hit with a dart just walking in the door – and sticks up for Matilda to get the best education possible.

Miss Honey’s efforts fail, but she’s not ready to give up. Surely Matilda’s parents know what a bright child they have and would want the best for her. However, Miss Honey finds the exact opposite is true when she goes to the Wormwood home. Mr. and Mrs. Wormwood scoff at the idea of Matilda taking advanced classes or attending college. In the movie, Mrs. Wormwood turns this into a slam at Miss Honey, implying she’s ugly and is left “slaving away teaching snot-nosed children” because she cannot succeed socially. Miss Honey doesn’t respond to this or stand up for herself, but indirectly stands up for Matilda. “Don’t sneer at educated people,” she scolds, pointing out that college-educated people provide necessary medical, legal, and other services. At one point, when Mr. Wormwood complains Miss Honey is keeping him from his television show, the teacher nearly loses her temper. Her voice shakes and does not rise much, but she risks voicing a truth the audience knows. “If you think some silly television show is more important than your daughter, then maybe you shouldn’t be a parent!” After slipping Matilda an advanced children’s book, Miss Honey leaves, more determined than ever to help her newest pupil.

Despite continual pushback, Jennifer Honey soldiers on with Matilda and the rest of her class. She continually imparts creative and memorable lessons. In these, her students not only learn academic skills like spelling, but how to problem solve (e.g., using a poem and mnemonic device to learn to spell “difficulty.”) Additionally, Miss Honey continues nurturing her charges, trying to bandage the physical and emotional wounds their principal leaves behind. For instance, she’s the one who sneaks out of class to get Matilda out of the Chokey, hugging her and making sure she’s okay. In a later scene, Matilda tries to confess to her teacher that her new kinetic powers tipped over Miss Trunchbull’s water glass. “Miss Honey, I did it,” she says solemnly after class. Miss Honey’s immediate, compassionate response is, “Don’t let Miss Trunchbull make you feel that way. Nobody did it; it was an accident.” The audience gets the distinct impression Miss Honey would say something like this to any child who ran afoul of the headmistress, even if that child had technically broken a rule or caused a scene. Later on, in a scene not included in the novel, we see Miss Honey try to take the blame for a student Miss Trunchbull targets, placing herself in immediate physical danger. However, it is not until the stakes are raised to climactic levels that we see Miss Honey’s true hidden strength.

In Matilda’s climactic scene, the title character uses her powers to make Miss Trunchbull think the ghost of Miss Honey’s father Magnus is haunting the classroom. This leads to some comedic slapstick, but also a serious standoff between Matilda and her headmistress. When it looks as though Matilda could be seriously injured, Miss Honey gets between them and Miss Trunchbull grabs her. “I broke your arm once before,” she threatens. It’s then that Miss Honey takes the biggest risk of all, revealing the secret that has influenced much of her life. “I am not seven years old anymore, Aunt Trunchbull!” she exclaims, wrenching away amid her students’ horrified gasps.

That simple sentence could have touched off any number of negative consequences. Trunchbull could have denied her niece’s accusations and attempted to get her into trouble with some higher educational authority. More likely, she could have harmed her niece irrevocably in front of the students, or taken her rage out on Matilda or the whole room of innocent kids. Whether Miss Honey thought through each ramification, we will never know. What we do know is what it cost her to admit her relation to Agatha Trunchbull. In admitting that relation, Jennifer Honey basically admits, “Yes, this person is horribly abusive. Yes, I was a victim. Yes, I had no way to protect myself, and yes, I know this could go badly for me. But something – someone – else is more important than my fear and victimization.”

Miss Honey eventually adopts Matilda, thanks to the little girl’s tireless research on the process. This is not an ideal or even realistic outcome for many students of lovely teachers, but it does drive home Miss Honey’s excellence. Were she a real person, Jennifer Honey would probably never say adopting Matilda was a sacrifice. She might say it’s the least she could have done, since Matilda was so instrumental in helping Miss Honey improve her quality of life. However, mature readers and viewers might see it differently. Miss Honey’s choice to adopt Matilda is the final piece of her heroic actions. She is no longer just an educator. She is a hero who puts her students, her children, first without question. When she couldn’t make a good life for herself, she chose to give up the relative freedom and safety of single-hood to provide it for a child. In fact, when she could have gotten away from her evil aunt for good, Jennifer Honey chose to go back into the trenches for the sake of children like the one she’d once been.

Few teachers in real life are so heroic, and few students will grow up to face the stakes Jennifer Honey did. While most teachers strive to put their students first, few will make the sacrifices she does. However, Jennifer Honey is a great example of what it means to look out for our fellow humans. She is an epitome of courage, kindness, and tenacity in the face of ongoing adversity. She teaches us to place others before ourselves and help when or where we can, even in tiny ways. Even her acceptance of abuse is a positive lesson. That is, as a child, Jennifer Honey had no way to protect herself from her aunt’s cruelty. She arguably never should have agreed to teach under this woman. But as an adult, Miss Honey does find the courage to stand up for herself, and use the skills she has honed to win against an adversary. She shows readers and viewers that intimidating and abusive though they may be, no human adversary is unbeatable if you have the heart, skills, and inner strength to defeat them.

Mr. John Keating, Dead Poets’ Society

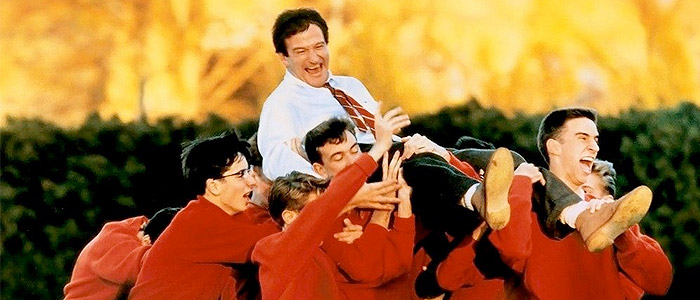

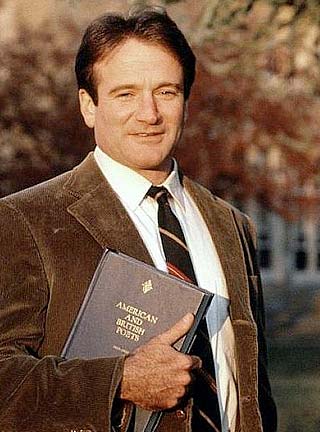

John Keating, portrayed by Robin Williams in the 1980s film Dead Poets’ Society, is the second of our discussion’s Good teachers. Like Miss Honey, Keating teaches in a strict and formal school environment, but unlike her, he is not a victim, nor does he protect students from outright abuse. Keating has a distinct advantage over Honey – he’s an alumni of Welton Academy, and has been passionate about teaching there for a while. When he arrives as the mysterious new English teacher, his fellow faculty are a bit cagey, but willing to accept him conditionally. As for the students, Keating wins automatic brownie points with them because he is so new and different. From the moment the boys of Welton step into English class with John Keating, they know this is not going to be their typical academy class or instructor.

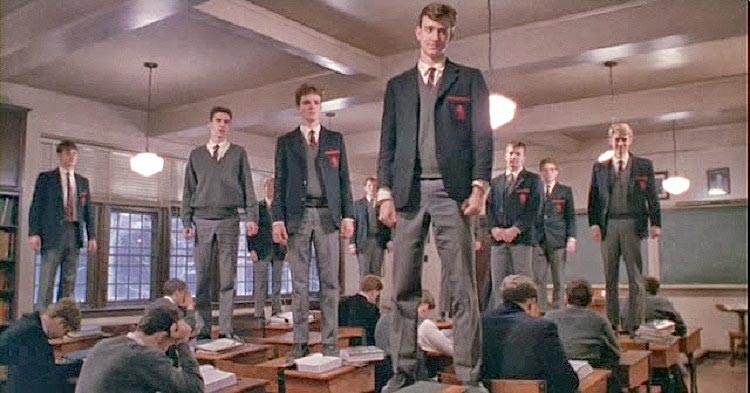

Many things Keating does are arguably for shock value. On the first day, he exhorts his students to rip out the entire introduction of their poetry texts. “Be gone, J. Evans Pritchard, Ph.D.,” Keating exclaims with a triumphant air. He calls the introduction “excrement,” based on Pritchard’s overly clinical analysis of poetry. “We’re not laying pipe,” Keating scoffs when some of his students hesitate to go against the grain. “You can’t rate it like American Bandstand…this is not the Bible, you’re not gonna go to hell for this!” Keating’s idea and delivery are highly unorthodox, but the boys buy it. One student dares to crumple up a textbook page and eat it. This incident helps Keating build instant rapport and give him the opening he needs for his true agenda. He’s at Welton Academy to teach English and specifically poetry, yes. But more importantly, he’s there to teach students who have been told what to think, how to do so for themselves. Unlike Jennifer Honey, John Keating sees no need to be subversive about this. In a refreshing contrast, he has plenty of fun doing it.

Throughout his tenure at Welton, Keating continues using creative exercises, prompts, and activities to get through to his class. We see the boys asking insightful questions, marching around the school chanting Army style, and forming their own Dead Poets’ Society based on their new favorite teacher’s school club. Keating’s place in their minds as the most fun and cool teacher they have ever had is permanently cemented. Yet, Keating is much more than a fun teacher, as students like Neil Perry and Todd Anderson learn as they get to know him one on one. These two boys in particular are in dire need of confidence and freedom, which Keating offers in bucket loads. For instance, he is the one who breaks shy Todd Anderson out of his shell. Keating recognizes Todd is introverted and may have reading problems, but never makes him feel ashamed of them. Instead, Keating coaxes Todd to unlock the brilliance he already possesses. The scene in which Todd crafts an impromptu piece about “a sweaty-toothed madman” is a prime example. In watching this scene, we learn what any benevolent teacher would want us to know. All students have brilliance, potential, and creativity inside them. Sometimes it takes the right environment, or the creation of it, to bring those qualities out.

Later on, Keating adds to this valuable lesson about potential and inner value, through his interacts with Neil Perry. Neil is a bright student who dislikes flouting rules. His authoritarian father has already laid out Neil’s future for him, a future that does not include poetry or Neil’s secret passion for the theater. Without quite knowing how or why, Neil turns to Keating for encouragement when his father’s expectations threaten to crush him. Over a cup of tea, Keating imparts implicit advice. He does not encourage Neil to go against his father, but exhorts him to “carpe diem,” or “seize the day” in his own way. The advice gives Neil the courage he needs to audition for, and perform well in, the academy production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Neil holds close Keating’s next lesson – while it is good to obey authority, at some point you will be called on to make your own decisions. At times, this will require courage, but you must take those opportunities while they exist, for tomorrow they may not be there.

Keating’s tenure at Welton does not end positively. Neil’s father severely castigates him for his role in the school play. Succumbing to pressure, Neil commits suicide, and although this isn’t stated, Keating seems to take some responsibility for that. Worse, the actions of a cowardly and somewhat traitorous student cost Keating his job. Viewers debate hotly over whether this was deserved – did Keating give Welton Academy something it needed, or did he do too much, too soon to shake up the system? Was he responsible with his students, and did he do right by them? Whatever the answers to these other questions, it is clear John Keating gave his students something they needed, and did something for them no one else could. He taught his boys they had the power to forge their own futures, that they were individuals, and that they could find and make the most of opportunities. In the span of a year, Keating did more to prepare his students for the real world than their other teachers probably had in decades.

Ms. Erin Gruwell, Freedom Writers

Our final Good teacher is a fictionalized representation of a real teacher, Ms. Erin Gruwell. Portrayed by Hilary Swank in the 2005 film Freedom Writers, Gruwell teaches freshman and sophomore English in a recently integrated 1990s high school. Although Gruwell is optimistic about her new teaching position and students – perhaps naively so – her fellow teachers are not. Department head Margaret Campbell immediately shoots down Gruwell’s ideas for texts, such as Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Homer’s Odyssey. “These reading scores…they’ll never be able to read that,” she says of the latter book. Indeed, according to test scores, the abilities of Erin’s students are abysmal. Many of them have no concept of basic grammar or literature. With the exception of one white student who everyone thinks of as “slow,” Erin’s students are all minorities. The majority participate in the gangs of inner city Los Angeles, or know someone who was or is in a gang. As Erin finds out the hard way, her students are far more concerned about staying alive than learning about universal truths in fiction. “You got no respect for how we livin’,” a freshman named Eva accuses her. Another student, Andre, says Erin is just “babysitting” the class, and that’s all she is expected to do. Erin’s attempt at reaching students on their level through basic grammar lessons fails miserably.

Some movies starring teachers take a scenario like this and imply it changes overnight. For Erin Gruwell, it does anything but. She has a long and difficult road ahead, but like our other Good teachers, she does not give up. She makes a brief inroad with a class-long session of The Line Game, which she uses to show her students what they have in common (many of them know the same movies and entertainers, many have been in juvenile hall or jail, and everyone in the room has lost at least one friend or loved one to gang violence). However, it is not until she invites the students to tell her their stories that true progress is made. Gruwell hands out simple composition books, encouraging the kids to fill them with stories, poetry, diary entries, or anything else that will help them express themselves. The diaries are ungraded, so the students can write more freely. The stories Gruwell uncovers threaten to send her running from her high school and from teaching altogether. She learns her students have never stood a chance at what she would term “normal” lives. One has been carrying a gun since fourth grade. Another accidentally shot a friend while playing with a gun they found in an alley; the cops sent him to juvenile hall because “all they saw was a gun, a dead body, and a [black kid].” A Cambodian-American student grew up in a refugee camp; “the camp stripped my father’s dignity,” she writes. After another student’s father loses his job, he makes her, her mother, and her young siblings go out to the concrete. “Pick a spot,” he says, declaring this is their new home. Gruwell is flabbergasted, wondering how her diaries, and high school English curriculum standards, can possibly make a difference to these kids.

Perhaps more than any other Good teacher we’ve discussed, Erin Gruwell has to be creative and persistent. When she finds a book her students can relate to, she’s not allowed to teach it in school, so must pay out of her pocket for everyone to have a copy. When her teaching salary won’t stretch to provide necessities, she ends up working three extra jobs. Gruwell often goes to her department head and principal with suggestions for things like curriculum changes and trips, but neither will listen. Department head Margaret Campbell contends Gruwell is “rewarding” her students for bad behavior, while her fellow teachers think she is being “ridiculous.” One teacher, who heads up the honors program, is offended when Gruwell teaches The Diary of Anne Frank to freshmen and sophomores who, like Frank, have had to hide to avoid abuse and gang life. “How dare you compare them to Anne Frank,” the teacher rants. “I’m the one locking my door at night!” He becomes further incensed when one of his students, Victoria, chooses to attend Erin’s class rather than his own. “Honors students are mine,” he insists, not bothering to admit he drove Victoria away when he used her race to patronize her.

Such constant resistance would wear the hardiest and most perfect teacher down, and Erin Gruwell does have discouraged moments, especially at first. “I’m not a social worker; what can I do?” she laments at one point. But she rallies, going straight to the district superintendent with the idea to take her students to a nearby Holocaust resource center. At this and other points in the film, she wins him over, and gets the chance to educate her students about the Holocaust and what it should mean for them. Over time, Erin’s tireless creativity and willingness to learn about her students inspire them to come up with their own ideas, such as fundraisers. Her class, room 203, becomes a community and refuge, to the point that the students lobby for everyone to stay together during junior and senior year. Gruwell and her students ultimately succeed, so Gruwell ends up teaching the same class for four years. But even if the students had been required to leave room 203 behind, they would have taken Ms. Gruwell’s most important lesson with them. Namely, they would have remembered that in fiction and real life, they are not alone. Everyone has a story and has the right to tell it. Most importantly, even if an event such as the Holocaust does not appear personal, there is always something to glean from it. There is always something to glean from others, even those you may have been taught not to trust.

The Bad

For every Good teacher, there exists a Bad teacher. We all remember our negative experiences with teachers, and they tend to stick in our minds as much if not more than the positive ones. Fiction tends to over-dramatize the Bad teacher, giving him or her more power and control than would exist in real life. The dramatization works though, because it helps play up the good lessons we can learn from these adults who truly have no business inside the classroom.

Ms. Agatha Trunchbull, Matilda

Since we began this article with Miss Jennifer Honey, it seems apropos to start the Bad teacher section with her polar opposite, Ms. Agatha Trunchbull. Trunchbull was stepsister to Miss Honey’s father, which makes the two family. As noted though, Trunchbull was never a loving aunt to Honey, choosing instead to abuse her throughout her lifetime. If Trunchbull’s abuse had stopped there, she would be reprehensible enough, but it extends to Crunchem Hall’s entire student body. Ms. Trunchbull is a headmistress, or principal in American terms, which gives her more power and arguably worsens her behavior. The mere sight of this woman sends students scampering across the playground for safety. They never make eye contact with her if they can help it, and they try their best not to be noticed. Those who are noticed pay for it. At best, they might get called a name like “fresh meat,” as Matilda Wormwood does on her first day at Crunchem. At worst, they might get thrown over a fence for something as trivial as wearing braids to school, like Matilda’s classmate Amanda.

If a student dares commit an actual misdeed on Trunchbull’s watch, he or she won’t soon forget the consequences. In perhaps the movie version’s most well-known scene, this happens to Bruce Bogtrotter, an overweight fourth-grader with a sweet tooth. Allegedly, he stole some of Ms. Trunchbull’s personal chocolate cake from the school kitchen and ate it. Any other principal might call the offending student’s parents or issue a detention; an especially compassionate one might ask Bruce why he felt the need to do what he did, and urge him to make appropriate restitution, such as working with the cafeteria staff. In contrast, Ms. Trunchbull calls a school-wide assembly to shame Bruce. She calls him up onstage, forces him to admit the crime (via the statement, “My mom’s [cake] is better”), and then decrees he will not leave the stage until he has eaten an entire giant chocolate cake. It appears the entire student body will have to watch as Bruce forces down the confection and then either gets violently ill or collapses, adding to his humiliation.

In the original book, Matilda simply watches this drama unfold with a combination of fascination and fear. In the film, she rallies the students, touching off a cheering session that helps Bruce finish the entire cake. As a result, Trunchbull makes the entire school stay five hours late to copy from the dictionary. In both cases, Matilda wonders how Trunchbull could possibly get away with this and other such outrageous punishments. She knows her own neglectful parents don’t care much, but is mystified as to why other parents say nothing, or why more people are not standing up to this tyrannical principal. An older student named Hortensia provides a telling answer. She explains the Trunchbull’s philosophy on punishment is to “go the whole hog.” In other words, Agatha Trunchbull purposely makes her methods so horrible no one would believe them, even when confronted with physical evidence like bruised and terrified children, or children who show up from school five hours late. To the Trunchbull, education is not a calling. It’s not an opportunity to mentor or nurture, or impart basic knowledge to elementary kids. For her, education is a power game. The Trunchbull has no concept of others’ feelings or needs; other people exist to make the world work for her. This includes children, whom she uses as pawns, often against compassionate adults like Miss Honey. Matilda finds that out the hard way in the film, when just being in the wrong place at the wrong time gets her thrown in the Chokey, a claustrophobic cupboard filled with nails and broken glass. Matilda is eventually able to use wit and telekinesis to beat the Trunchbull at her own game, but Crunchem Hall’s students may never quite recover from their headmistress’ tyranny.

What could such a sadistic, over-the-top pseudo-educator have to teach readers and viewers? Surprisingly, there’s much to be gleaned from Agatha Trunchbull. The first and most obvious lesson we can take from her is that teaching, and life, is not about power. Even if you are in authority over others, that authority should be used to lead and direct, not subjugate and terrorize. Beyond that though, the Trunchbull is a cautionary tale about what happens when someone thinks he or she is invincible. “In this classroom…in this school…I…AM…GOD!” The Trunchbull screams on one occasion. Indeed, she’s treated as such – until little Matilda comes at her with smarts and understated sweetness. Agatha Trunchbull can understand neither of these things. She doesn’t know how to fight them effectively, and so they defeat her. Unconsciously, she left a huge chink open in her armor, which allowed Matilda, Miss Honey, and other protagonists to eventually dismantle her persona. Matilda thus becomes a true David and Goliath story, with perhaps the most formidable Goliath children’s literature, and the fictional education system, has ever seen.

Miss Maria Minchin, A Little Princess

Maria Minchin of Frances Hogsdon Burnett’s beloved novel is another Bad teacher with more power than usual. Interestingly, she’s a combination teacher and principal. She owns and runs Miss Minchin’s Select Seminary for Girls, but also teaches several of its classes. In the 1995 film version of A Little Princess, we actually see her act far more as teacher than headmistress, supervising classes while enforcing school rules and overseeing her pupils’ social development. Unlike Agatha Trunchbull, Miss Minchin devotes a lot of time to actual teaching, and appears fairly competent at it. The problem is, she intimidates her students and focuses her dislike on one student in particular.

That student is little Sara Crewe, who comes to the Seminary at age seven (in film versions, which condense the novel, she’s between ten and twelve). At first, Miss Minchin dotes on her. Sara’s father Captain Crewe is incredibly wealthy, making Sara one of the most well-heeled pupils in school. In the Victorian era, where the book and film are set, this would have meant a huge pay increase for Minchin, who immediately sees Sara as a lucrative cash cow. But in short order, Minchin learns her newest meal ticket is more trouble than she bargained for. Minchin expects Sara to act spoiled and rebellious; instead, the girl is bright, exuberant, and unfailingly sweet. She quickly befriends the school outcast Ermengarde, and becomes a mother figure to little Lottie, the youngest student who is prone to tantrums. Like Agatha Trunchbull before her, Maria Minchin cannot comprehend Sara and thus, sees her as a threat. Only Sara’s father and his accompanying money stand between Sara and Minchin’s true colors, though not for long.

Miss Minchin has a distinct advantage over Ms. Trunchbull, in that she gets to act out her frustrations with Sara long-term. When Sara’s father dies, Minchin is prepared to turn her out into the street. When Captain Crewe’s attorney suggests Sara be made a servant instead, Minchin jumps on the opportunity. She demotes Sara to scullery maid or, as Burnett calls it, “maid of all work.” Along with the other maid Becky, Sara is worked to the bone, starved, and occasionally physically punished over a matter of months. Sara’s spirit remains unbroken, but barely. Burnett muses if not for Ermengarde and Lottie, and her own imaginings of herself as a princess, Sara would have met a dire end. She might not have died physically, but would have succumbed mentally and emotionally, leading to a nervous breakdown. This becomes even more evident when Minchin expects Sara to act as a teacher for the younger girls, but refuses to pay her. Those who take in Sara’s story are meant to understand Minchin will permanently indenture her, because her father’s debt can never be paid.

Sara is eventually rescued thanks to a friend of her father’s, Mr. Carrisford, and finds refuge at the Carrisford home, where she is adopted and finds her fortune restored. Miss Minchin attempts to bring Sara back to the school once she regains her wealth, but Sara refuses. Minchin is never heard from again. The conventions of the Victorian novel imply she doesn’t deserve to be heard from – she will be miserable ever after because of how she treated Sara, and that is that. Some film adaptations give her comeuppance; in the 1995 film for instance, Minchin ends up working as a chimney sweep after she loses her school to Sara’s benefactor. Whether she gets comeuppance or not though, we are meant to learn something from Maria Minchin.

In the 1985 BBC version of A Little Princess, Minchin’s sister Amelia puts the lesson beautifully. “You’re a hard, selfish woman,” she claims, echoing the original novel. “I only hope the other pupils will not follow your example.” Indeed, what a terrible example it is. Miss Minchin is as abusive as the Trunchbull, if more subtle, but her mistakes go far beyond treating teaching like a power game. Maria Minchin is a desperately insecure woman living in a society where financial status is king. She’s already financially comfortable, but doesn’t appear content with her station. She wants to break into the upper echelons of society – in some ways, to gain some measure of princess-hood for herself. Yet instead of getting it the right way as Sara does, Minchin uses innocent children as steps to help her climb the social ladder – and steps on them in the process. She’s also unwilling to use the resources she already has to benefit anyone else; she could have let Sara stay on as a pupil, paid her to teach, and mentored her. Perhaps then, once Sara’s wealth was restored, she would have urged Mr. Carrisford to show her former teacher kindness. Minchin could have had the recognition and respect she so longed for, with fairly minimal effort. Instead, she chose to benefit herself in the short run while in the long run, decimating her chances of happiness.

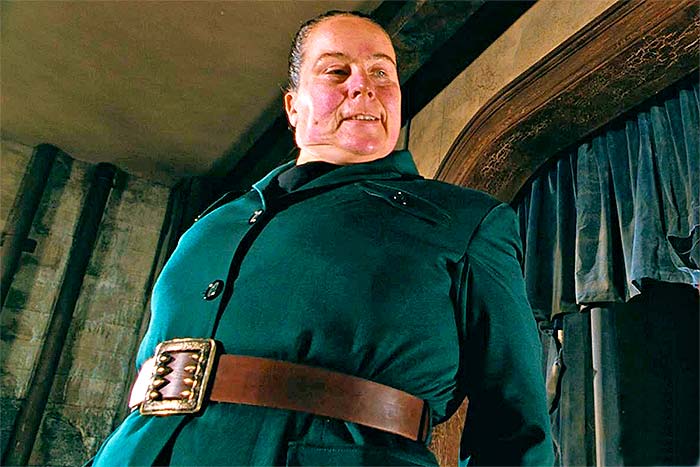

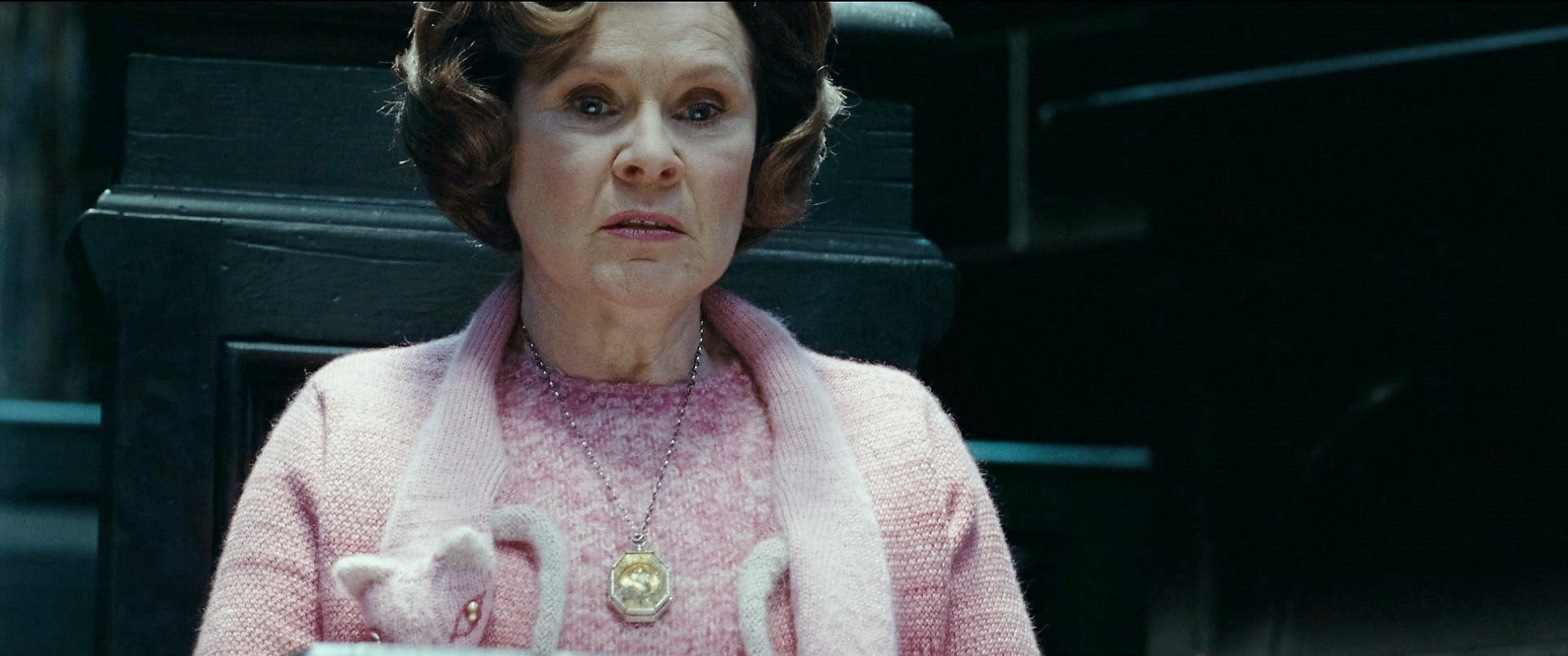

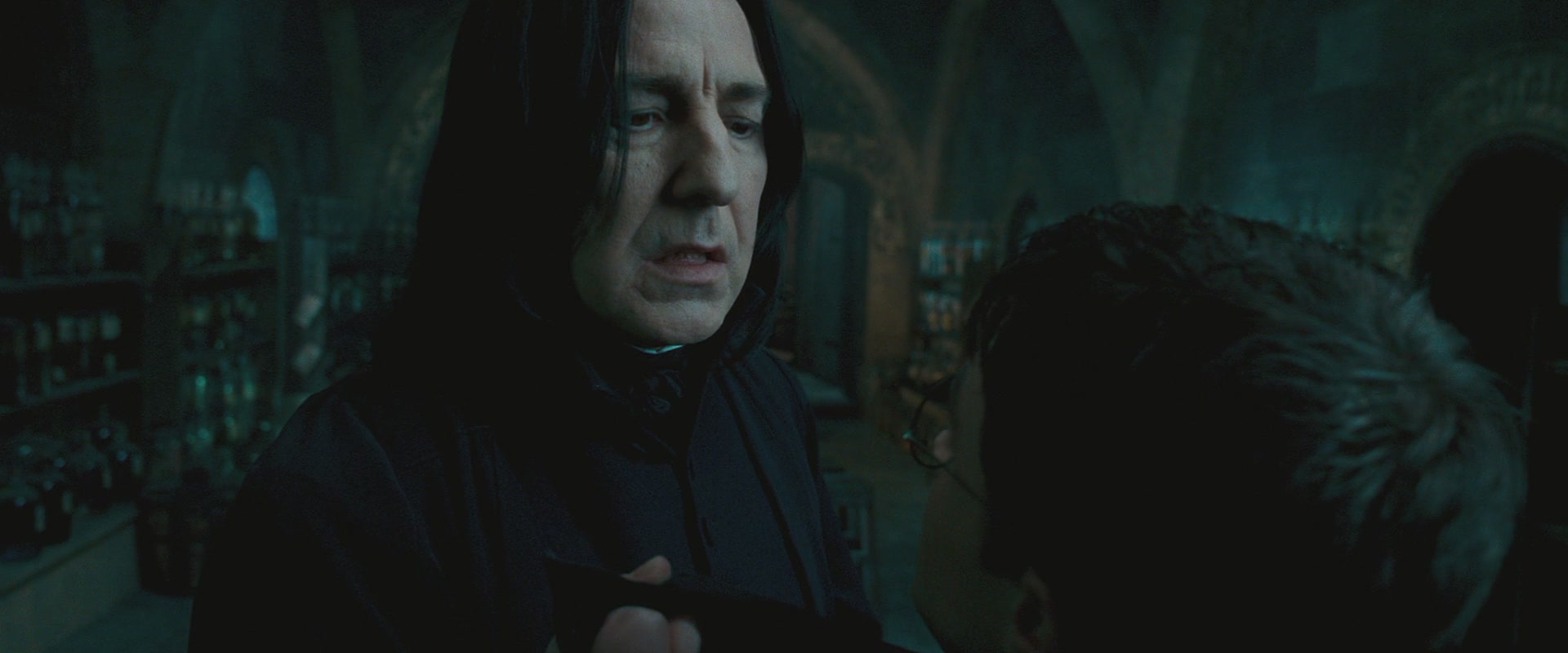

Professor Dolores Umbridge, Harry Potter Series

Of the Bad teachers on our list, Professor Dolores Umbridge is probably the worst. Most Harry Potter fans despise her, and some claim they wanted her dead more than Voldemort. As one anonymous fan puts it on a forum board, “Umbridge is personal.” She’s not all-powerful like Voldemort; she does not commit crimes her students may have only heard about. She, more than perhaps any other on this list, is the embodiment of the unreasonable authority figure we have all faced. She’s the teacher who punishes an innocent student for a classmate’s behavior; the boss who overloads you with work and then berates you for not keeping up; the smarmy coworker who couches backstabbing as compassion.

Dolores Umbridge was a Ministry of Magic plant, and eventually becomes Hogwarts’ headmistress. In fact, this seems to be a common trait among Bad teachers. If they can claw their way to the next level, they will, just to spread their negative influence while making themselves look good. Like Trunchbull and Minchin though, Umbridge has qualities that give her brand of Bad teacher a certain uniqueness. For instance, she’s the only one of the three we have discussed who looks and acts congenial with everyone at first. She doesn’t show her cards immediately, nor does she single out one student for good or ill. With her soft voice, delicate cough, bubblegum pink ensembles and love of kittens, Delores Umbridge seems like everybody’s sweet, cute grandma. You half expect her to wave her wand and conjure Werther’s caramels out of the air. Instead, Umbridge deals exclusively in well-masked poison that emotionally damages any student or teacher unlucky enough to swallow it.

Like our other two Bad teachers, Umbridge is not above handing out draconian punishments. Her methods are infamous, even among non-Potterheads. She’s particularly known for making students write lines with an enchanted quill, which carves their infractions into their arms using blood. Harry Potter came away scarred and seething after a detention in which he was forced to write, “I must not tell lies” repeatedly. Additionally, Umbridge loves Veritaserum, a potion that forces people to tell the truth. She uses it indiscriminately, forcing students to give her information that might lead to betrayal, heartbreak or even physical danger. But if Umbridge’s methods stopped there, she would not have made the list. Over-the-top punishments from adults are fairly commonplace in education-centered stories, partially because they give the heroes something intense to fight against. They also increase the heroes’ sympathy factor, because even the most law-abiding adult would not expect a student to indefinitely accept such abuse.

Dolores Umbridge is a Bad teacher mostly because she functions in denial mode. She was originally hired to teach Defense Against the Dark Arts, a class her students need for basic survival after Voldemort plots his return. However, Umbridge refuses to hear any talk of Voldemort coming back, and silences anyone who dares contradict her. Like many misguided educators, she only teaches straight from the textbook and expects her students to regurgitate it. She does not allow her classes to put theory into practice, nor does she let them ask intelligent questions or discuss what they are supposed to be learning. Umbridge’s classroom is less a place of learning than a holding pen, and the students can sense it from day one. Worse, Umbridge tries to justify her actions with the mindset that “they’re just children.” In fact, she treats her students more like easily frightened five-year-olds than teenagers. She builds no rapport with them and has no concept of what anyone, especially Harry, Hermione, and Ron, have already gone through to protect themselves and their school.

More than any Bad teacher on our list, Dolores Umbridge is personal. Agatha Trunchbull is an equal opportunity abuser; if you are in her school, you are considered fair game. Maria Minchin singles out Sara Crewe for abuse, but only because Sara failed to give her what she expected and wanted. Dolores Umbridge has no such parameters. She’s a cold, calculating individual who uses the conventions of education to hurt everyone, but only in the most painful ways. She knows where everyone’s buttons are, where to push, and how hard. She also has a dubious talent for making everyone her victims, while simultaneously making one person feel as if it’s all their fault everyone else is suffering. Harry Potter is a prime example, since his assertions of Voldemort’s return place his friends and trusted teachers in the line of fire. However, Umbridge plays this game with almost everyone, from Hermione Granger to Sybil Trelawney and even formidable colleagues like Severus Snape.

Umbridge’s way of making abuse personal means it’s she who has the most difficult, yet vital lessons to teach readers and viewers. For real-life educators, she may hit a nerve. Ask an educator and he or she will probably vent frustrations about teaching to tests, or making students regurgitate information because there isn’t time for much else. Many well-meaning educators also underestimate their students, relating to them as children when they have already handled some unusually adult problems. The key difference is, most fictional and real-life educators do not want to treat their classrooms as holding pens. They, unlike Umbridge, want their students to function in the real world, to learn something of value, and to trust their teachers. Thus, Delores Umbridge becomes a wonderful portrait of what not to do as an educator.

Umbridge has plenty to offer for non-teachers, too. Her refusal to face the difficult truth about Voldemort reminds us that sometimes, knowing the hard truth is the greatest power we have. Once we know the truth, we can become responsible for it and act on it, making our fears less powerful. Additionally, much of what Umbridge does comes from a place of fear and desire to maintain control in a chaotic world. Everyone has felt that way at some point, and we’ve probably hurt others in trying to cope, although we may not have used enchanted quills to do it. Umbridge reminds us that when the world gets chaotic, it’s okay to be afraid, but tightening control is never the answer. Rather, we must be willing to become vulnerable, to get on the level with people and say, “I’m scared, too.” We also need to make ourselves available to others so we need not face chaos, danger, or new situations alone. Working alone can sometimes come across as being arrogant or uncaring. On the other hand, building rapport and sharing what you know encourages others to trust you. It builds friendships, partnerships, and teams, all of which make the world outside of school easier and safer to navigate.

The In-Between

Finally, some teachers do too much good to be Bad teachers, but they have not yet reached the level of character it takes to be a fictional Good teacher. This can happen for several reasons. Often, it’s because the teacher is human, and lets his or her human side show more in the classroom than is good or necessary. Sometimes it’s because the teacher focuses on issues outside the classroom, whether out of necessity, selfishness, or boredom. In-Between teachers remain notable though, and are sometimes more favored than their Good counterparts. Whether favored or unpopular, they are certainly remembered.

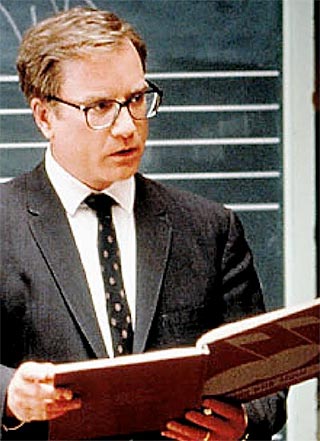

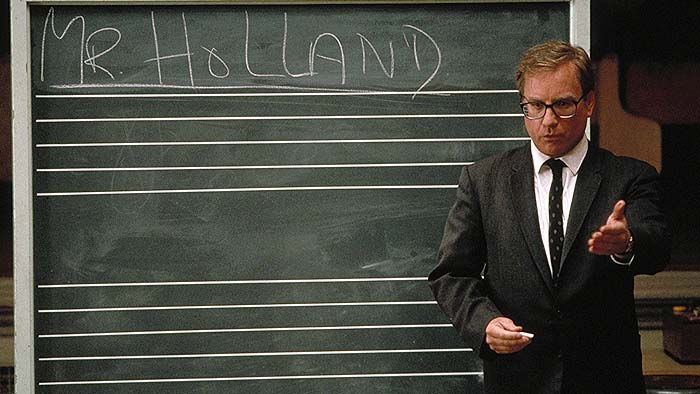

Mr. Glen Holland, Mr. Holland’s Opus

Mr. Holland’s Opus, released in 1995, is not the oldest teacher-centric story out there, but it might be one of the best known. Its protagonist is Glenn Holland, portrayed by Richard Dreyfuss. Holland dreams of becoming a famous composer, but currently needs income steady enough to pay the bills. With this in mind, he takes a job teaching music at a local high school, thinking it will be easy. He calls it a “fallback” until composing takes off, but his principal, Helen Jacobs, is not impressed. “Mr. Holland, I don’t consider teaching a ‘fallback’ position, and I grow nervous around people who do,” she warns. Duly chastised, Holland tries to prove himself, but finds the job much harder than it looks. He leans too heavily on the textbook for classes like music appreciation, and he can’t inspire his fifth period orchestra to put forth the effort and passion they need to do well. Not long into the job, he comes home and tells his wife, “I hate teaching, I hate it! They just sit there staring up at me…there’s no ‘there’ there!”

A Bad teacher might take this opportunity to be lazy or vent his frustrations on his students. Holland does neither, but keeps plugging away in a less than inspired manner. For example, he tries to help clarinet player Gertrude Lang, who is so anxiety-ridden she can’t perform a required graduation piece. She stays after school, playing through tears, and Holland pokes his head in to say, “Give it up, Miss Lang!” Gertrude takes this as the brusque comment it is, and her confidence is decimated. Yet to his credit, this is one of the moments where Holland starts to embrace teaching. He apologizes and takes time to coach Gertrude through her anxiety. “Is it any fun?” he asks of playing the clarinet. When Gertrude admits it’s not, Holland gets her to open up about the pressure she feels to do as well artistically as her gifted parents and siblings. He then asks Gertrude what she likes most about herself. “My father says [my hair] always reminds him of a sunset,” she says of her distinctive red locks. Holland advises her to “play the sunset,” and Gertrude gets through the piece she was trying to play. Better, she gets a much-needed dose of confidence, learning she is more valuable for who she is than what she can do.

From this point, Glen Holland embarks on a decades-long teaching career at John F. Kennedy High School. Interestingly, his triumphs are often mixed with setbacks and vice versa. For instance, he is challenged to let one student, Lou Russ, play in marching band so Lou can get an academic credit and stay on the football team. Once again, Holland easily gives in to his frustrations when Lou has a terrible time learning to keep rhythm on the drums. Bill Meister, Lou’s coach and mentor, pushes Holland to keep trying. “I can’t,” Holland protests. “Well then, you’re a lousy teacher,” Meister fires back. This, plus Lou’s tireless determination, is the push Holland needs; he uses every method possible to help his student learn to play. One humorous clip shows Lou wearing a football helmet, which Holland pounds with a felt-tip mallet. Over time, Lou and Holland learn to understand each other, and Lou manages to succeed in band, on the wrestling team, and academically. When he is sent to Vietnam shortly after graduation and is killed, Holland feels the blow as keenly as any loved one. But like any Good teacher, he uses the setback to fuel another triumph. Holland forces another student, a perpetually stoned troublemaker named Stadler, to come to Lou’s funeral as part of a disciplinary assignment. We don’t know exactly what Stadler gleans from this, but he never makes trouble in music class again. Years later, he’s one of his former teacher’s supporters when Holland is forced into retirement.

The final thing that makes Holland an In-Between teacher instead of a Good one is how devoted he becomes to his students over the years. The more he teaches, the more he loves it, and the more time he spends away from his family. Midway through Mr. Holland’s Opus, Holland’s wife gives birth to a son they name Coltrane Gershwin, or Cole for short. Holland can’t wait to share the joys of music with his son, and is devastated to learn Cole is 90% deaf. Holland is often aloof and distant with Cole, not knowing what to do with a son who can’t share the biggest and best piece of his world. He leaves much of the work of raising a deaf child, such as learning sign language and communicating with teachers, to Iris. At one point, Holland’s longing for someone to share music with leads to a tryst with Rowena Morgan, a senior and gifted singer. We’re meant to assume Rowena is eighteen and thus a consenting adult; Holland is never reprimanded for his actions, and his wife never finds out, although plenty of clues point to her suspicions. However, the fallout of the tryst and his actions stay with him, especially where Cole is concerned.

As Cole grows up, he and his dad grow further apart. The tension boils over when Cole is around fifteen or sixteen. By then, Holland has learned enough sign language to get by, and Cole can speak enough to maintain communication. One bleak day, Holland comes home depressed because John Lennon has died. “You wouldn’t understand,” he tells Cole when his son inquires. In a rage, Cole vents his feelings with Iris as interpreter. “You think because I’m deaf, I can’t understand. I know what music is. You could help me to learn it better, but…no,” he exclaims. He finishes by throwing a curse word at his dad and storming out of the room.

Once again, it takes a fairly dramatic event to push Holland in the right direction. He eventually makes up with Cole and works out a way to share music with his son, using signing, vibrations, and colored lights. By the time Holland retires in the wake of the music program being cut, both his students and family are firmly in his corner. They are aware of what a special teacher he has become and how he has grown as a person. As viewers, we see the same thing, and have probably learned some lessons from Mr. Holland just like his students have. The most obvious concerns keeping our priorities straight; Holland’s failure to do so is a huge cautionary tale. The more important lesson, however, stems from the way Holland “grows into” teaching. “I got dragged into this gig kicking and screaming, and now it’s the only thing I want to do,” he tells colleague Bill Meister near the end of the film. Like Holland, we may find ourselves being pushed into something like a career, or parenthood, or a new path in life, that we go into “kicking and screaming.” But like Holland, if we give the new path a chance, we may find it’s the best thing that ever happened to us. We may find our own opuses waiting for us at various points, as Mr. Holland did with his students.

Ms. Roberta Guspari Demetras, Music of the Heart

Roberta Guspari Demetras is another fictionalized teacher based on a real person, a violin instructor of elementary children in Harlem, NY. Music of the Heart, the docudrama based on Demetras’ life and teaching, was released in 1998. Perhaps because she is based on a real person, Meryl Streep’s portrayal is more human and “in-between” than it would be if Roberta Demetras were entirely fictional.

When we first meet Demetras, her husband has cheated on her with a friend and absconded, leaving her to raise her seven- and five-year-old sons. Demetras has a teaching certificate, but living with a Navy husband has kept her from getting the necessary experience to teach violin classes in schools. Despite this, she is determined to land a job at an alternative elementary school in Harlem. Armed with a philosophy that any child can learn to play the violin, Demetras performs an impromptu piece with her sons, showing her prospective principal how well she taught them. Principal Janet Williams is impressed enough to give Demetras the job on a substitute’s salary, and the first violin class of Harlem is born. However, it has been a while since Roberta Demetras taught, and to our knowledge she has never taught elementary kids. As with Glenn Holland, her inexperience and insecurity show in a variety of good decisions and costly mistakes.

Demetras, or Roberta as her students will call her, begins her first class passing out violins. However, she does not appear to give instructions on violin care or set classroom expectations before letting the kids at the instruments. The room devolves into chaos, with fifty kids pouncing on the instruments, using the cases as fake machine guns, and plucking the violins instead of playing them. Roberta literally pleads for attention, and only gets it during a natural lull in the noise. She finds one little boy, in about the first grade, still scat singing and drumming on some boxes in the corner. In most cases, a teacher in Roberta’s place might say something like, “No talking while I’m talking” or, “Pay attention, please.” Instead, Roberta calls the child over, tells him to go to the office, and permanently kicks him out of her class. Bear in mind this child is quite young and has never been in a violin class before. Roberta may also have squelched some natural musical gifts by kicking him out too soon. While the example works, it is definitely on the harsh side.

Roberta’s “fly right or get out” policy continues for the rest of the film, with mixed results. At one point, a student named Vanessa forgets to bring her violin to class one too many times, so Roberta drops her with no warning (we do not know if she had made her policies on this clear before). Later, Roberta finds out Vanessa is going back and forth between her divorced parents’ houses and having trouble keeping up. She apologizes and lets Vanessa back into class, but one wonders why she, as a divorcee herself, did not show more empathy or at least ask Vanessa beforehand why she forgot her violin so often. In another example, her constant refrain of, “Your [poor playing] is gonna make your parents sick” upsets student Becky Lamb so much, she reports to her mother. Mrs. Lamb shows up in the principal’s office, accusing Roberta of abusing the students. After a gentle but firm reprimand from her principal, Roberta agrees to “soften [her] comments to the children.” When she tries though, it comes off as forced and phony, so that even the kids notice and protest. Interestingly, Becky is the one who declares, “This is even worse; you’re acting weird now.” Roberta goes back to being herself, but only after exacting a promise from the relieved kids that they won’t tell their parents what she says in class. No teacher should act overly sweet to get kids to like them, but again, one wonders if Roberta’s approach was correct. As we see later in the film, she continues to struggle balancing firm and fair, even after ten years on the job. She often comes across as caring more about the technique and integrity of violin-playing than the students behind the instruments.

This is not to say Roberta doesn’t have great moments, though. In ten years of teaching violin, she proves she more than has what it takes to motivate and inspire her young charges. For instance, one of her first students is a girl named Guadalupe who wears leg braces. Thus, Guadalupe cannot perform the correct violin-playing stance. Roberta suggests she sit down to play, but for Guadalupe, this is another sign that she is different and less than the other kids. One morning, she slips into Roberta’s classroom alone to practice, and expresses her feelings when Roberta asks why she’s there. “Everyone is better than me. I’ll always be weaker,” Guadalupe laments. In response, Roberta shares the example of Yitzchak Perlman, a real-life violinist who had polio as a child and now uses two canes to walk. “He still makes the most beautiful music,” Roberta says. She adds, “You shouldn’t quit something just because it’s hard.” Guadalupe takes the lesson to heart and continues working hard in violin class. Better, Roberta herself is inspired to do better by her students; up to then, she had been poised to quit her job over the stress of an impending divorce.

Ten years later, Roberta gets the chance to make a lasting impact on another student, through a mixture of mistake and triumph. The mistake occurs when she yells at student Justin and threatens to keep him out of the big spring concert. Granted, Justin often makes trouble in Roberta’s class, but Roberta’s knee-jerk reaction startles the other kids and disrupts learning. This is compounded when fellow student Ramon shouts, “Drop dead, Justin!” The scene cuts away from class at that point, but in the next one, we learn Justin was killed in an offscreen drive-by. Ramon is understandably subdued in class, and Roberta goes to his family’s apartment after school to check on him.

“I’ve been thinking about Justin,” Roberta tells Ramon when they’re alone together. “Remember how mad I was at him?” Ramon agrees, and expresses his guilt at having told Justin to drop dead. “Justin didn’t die because you said that,” Roberta reassures him. “You’re not that powerful.” Ramon is somewhat reassured, but questions whether Justin is in heaven or hell. Roberta assures him the other boy is in heaven, and reassures Ramon it’s okay to cry when she sees the boy is close to breaking down. When Ramon asserts men can’t cry, Roberta shows extreme empathy. “My boys still cry, and they’re big…now. And I’ll bet Justin’s daddy cried,” she says. She gathers Ramon in her arms, providing much-needed comfort and adding a layer of humanity to her previous knee-jerk strictness.

Like most In-Between teachers, Roberta Guspari Demetras sometimes lets her own feelings and foibles get in the way of her job and relations with her students. Yet some of her best lessons for teachers and non-teachers come from her worst mistakes. Her habit of kicking out misbehaving students reminds us that at times, grace is the order of the day rather than stringent rule-following. It also reminds us to make our expectations clear as soon as possible because other people, especially children, are not mind-readers. Perhaps most importantly though, Roberta Demetras reminds us the things we’re passionate about, like the violin, are not just subjects we can share with others. We can also use our knowledge to help those around us become better, stronger people, or inspire them to do things they thought they couldn’t before.

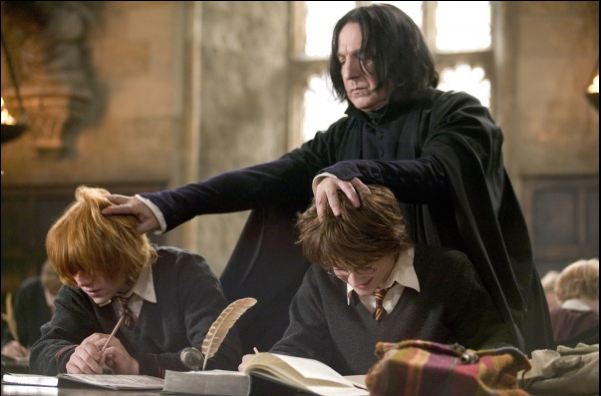

Severus Snape, The Harry Potter Series

This last entry on the list was the most difficult to place. Severus Snape is nothing if not complex. J.K. Rowling herself says, “Snape is morally grey. He’s not a saint; he was a bully.” Yet many of Snape’s other actions prove he was no more evil than he was a saint. From how we see him act in the classroom, we might be tempted to call him a Bad teacher, and most fans would say this is justified. Even fans who grow to love Snape as a person will not excuse or defend his behavior around students. At the same time, a lot of fans admit Snape makes some choices in and out of the classroom that redeem him as a person and educator.

If we stick directly to Snape’s behavior as a teacher, there’s little if anything to recommend him. He bullies and intimidates his students from the moment he meets them, calling them “dunderheads” and predicting that almost everyone will fail his Potions classes. That’s anything but a confidence-builder, especially for first years like Harry Potter and his friends Hermione and Ron, who are already nervous and turned off by their instructor’s grim, black-cloaked appearance. Snape is also infamous for picking on certain students while blatantly favoring others. He singles out Harry for ridicule constantly, finding any excuse to give him poor grades. At one point, Snape even blames Harry for an accidental spill he himself caused, and gives Harry a zero. Meanwhile, he showers points and begrudging good will on students from his own house, Slytherin. He isn’t completely lenient, but he’s far more likely to excuse someone like Draco Malfoy’s bullying behavior than he is to believe a student like Harry when the latter reports it.

If it were only Harry Potter Snape picked on, readers and viewers might excuse it. They might assume someone as celebrated as Harry needs a formidable adversary, or at the least, someone who doesn’t buy into the whole “Harry’s special because he’s famous” narrative. They might even excuse Snape’s favoritism of Slytherin; after all, he is kind of the “den dad” for that house and probably feels a responsibility toward “his” particular group. However, Snape’s acerbity, sarcasm, and downright meanness spread to almost every Hogwarts student. On one occasion, he mocks and shames Hermione because of her large teeth, and we find out Neville Longbottom is so scared of him, Snape appears as his boggart during Defense Against the Dark Arts. Note that Neville has seen his parents tortured into insanity and has more reason than most students to fear someone like Voldemort. The fact that he fears his Potions teacher more than a zealot wizard who could obliterate the entire school, nets Snape another strike.

Snape doesn’t reserve his sour attitude and pettiness for students, either. During Prisoner of Azkaban, Harry and friends study Defense Against the Dark Arts (DADA) under Professor Remus Lupin, a knowledgeable yet congenial teacher and perhaps the most approachable Hogwarts has yet seen. For the first time, the students in Harry’s year learn useful things in this crucial course. Yet Snape, who went to school with Lupin, knows the other man’s secret – he is a werewolf. As such, he is classified as a dangerous creature under the Ministry of Magic’s bylaws. Lupin was also a good friend of James Potter, Harry’s father and Snape’s own school bully back in the day. Snape uses this as motivation to “out” Lupin publicly and force him to resign. Most readers and viewers cite this as enough reason to despise Snape 100% – they equate it to a petty coworker getting a disabled or disadvantaged colleague fired out of spite. It doesn’t help Snape’s case that Rowling has stated Lupin’s lycanthropy is a stand-in for HIV – a treatable illness that should no longer keep people with it from holding jobs or participating in society.

With so much against him, readers and viewers might well wonder what Snape could do to keep himself off our Bad list. In a twist, a lot of the answer goes back to Harry Potter, the one student Snape seems to hate above all others. In Deathly Hallows, readers learn Snape once swore to protect Harry because of his deep love for Lily Evans, who would later become Harry’s mother. Harry is Snape’s last link to Lily, so protecting him is a way of keeping her alive. However, doing so necessitated that Snape go deep undercover. Even if he wanted to, he could not be a stereotypical warm and wise mentor to Harry. He is acting as a double agent, spying for Dumbledore while pretending to keep up his old Death Eater persona under Voldemort. Thus, Snape must be extremely sneaky in his benevolent efforts, and pull them off with precision.

Throughout the seven Harry Potter books, Snape consistently protects Harry and friends without their knowledge. In Harry’s first year, Snape goes head to head with Professor Quirrell when the latter attempts to jinx Harry’s broom in a Quidditch match. From the stands, it appears Snape is jinxing the broom; in the film, we see his mouth move every time the broom goes rogue. But Quirrell is in the stands too, and he’s muttering spells almost in sync with Snape. Hermione gets credit for saving her friend with a well-placed spell, but Snape holds off Quirrell’s jinx long enough to give her an opening. A similar incident occurs in Prisoner of Azkaban. This time, Snape follows Harry, Ron, and Hermione to the Shrieking Shack just before the final battle. Lupin, on hand to fight traitor Peter Pettigrew, has forgotten his wolfsbane potion, transforms, and tries to attack the kids. Snape gets between them, shielding the students behind his cloak. He may not like these students, especially Harry. Yet here, he proves he possesses a strong if latent Good teacher instinct – put yourself in harm’s way before letting your students get hurt.

Snape continues mentoring Harry on the sly as the latter grows up and hurtles toward his final battle. Many of his actions in Half-Blood Prince point to this. During HBP, Snape has turned over Potions to Professor Horace Slughorn in favor of his dream job, teaching DADA. In the meantime, Harry gets his hands on an old Potions textbook filled with personal notes, diagrams, and invented spells, some of which he uses to improve his DADA and dueling skills. Harry and readers eventually learn the mysterious Half-Blood Prince behind the notes is Snape. On further analysis, it becomes clear Severus Snape was a Potions genius as a student, and one of the only professors who ever taught his classes without using a textbook. His personality may be awful, but Snape is at his core an innovative, passionate teacher who can be a big help when he relaxes enough to think no one’s looking. This comes out in a few other key scenes, like when Snape inadvertently teaches Harry Expelliarmus, his signature spell.

Unfortunately for Snape, it takes catastrophic events to bring any of his better instincts to the forefront. This mostly happens in Deathly Hallows, wherein Snape basically serves as a puppet headmaster under Voldemort. Again because of deep cover, he must appear to support the regime; he brings in two sadistic Death Eater professors as proof. At the same time, he constantly protects students underhandedly. He sends Neville Longbottom into protected areas of Hogwarts at crucial moments, knowing the Death Eaters consider him a marked man. For the first time, Snape reprimands Draco for calling Hermione a “mudblood,” promising dire consequences for anyone else who uses the slur. And of course, he keeps a watchful eye on Harry Potter. Harry is in fact the one Snape trusts most with his memories when the latter is near death. Along with Harry, readers learn the courageous actions Snape took to protect the school that became his somewhat unwilling refuge.

For a lot of fans, Snape’s Good teacher actions are too little too late, while for others, they are a crucial piece of his redemption. Either way, Snape may impart the most complex lessons of anyone. The idea that it’s never too late for redemption provides the emotional arc for his story. As a teacher, he also represents the need to make good choices as early as possible. That is, had Snape turned from Voldemort sooner, or simply tried to build rapport with students, maybe he’d have attained the acceptance he always craved. Making the early choice to put students first may not make you a hero, but it will ensure your mistakes are more easily forgiven and your good choices remembered without tainting. Either way, Severus Snape is the perfect example of an educator who must walk the tightrope between professional and personal obligations. He often falls, but when he stays balanced, readers and viewers actually cheer for him more.

The Final Grades Are In

All of us have teachers we will never forget. Some were the Good teachers who made us feel safe, worthwhile, smart, or talented. Some are the Bad ones who taught us what not to do. Still others were In-Between teachers who made mistakes as often as they inspired us, but managed to leave good impacts. This is perhaps truer in fiction than in real life, as fiction gives us such multifaceted examples who offer diverse life lessons. No matter whether your favorite fictional teacher gets an A+, an F, or something in between, he or she will likely stick with you forever.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I love Jaime Escalante from Stand and Deliver, portrayed by the excellent Edward James Olmos, because it’s too easy to present the poetry of poetry, but much harder when you’re talking about algebra.

I like Stand and Deliver too, but didn’t use it because I’ve only seen it once.

Thank you for not discussing Mona Lisa Smile which may be one of the worst films I have ever been subjected to.

@Mittie: I almost did, because some people consider it “Dead Poets’ Society for women.” But I like DPS much better.

Actually, if there is a “Dead Poets Society for women”, that would be “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie”.

Am interesting discussion would be one comparing Wilshaw to Deloris Umbridge (who incidentally had Snape on probation) and asking how Miss Jean Brodie would fare in today’s climate ‘re radicalisation and encouraging students to fight in foreign wars

Snape was never on probation. He was a good teacher despite his unpleasant character. Umbridge was appalling in every sense.

Umbridge put him on probation in her office being deliberately unhelpful to her (not providing her with more truth serium, which he couldn’t do because it was impossible). I think many teachers up and down the country are being put on capability for similar reasons, as long as you replace ‘making truth serum’ with ‘marking excessively and getting unrealistic grade predictions’

I think john in dead poets is a good teacher in the sense that he brings out a thirst for learning and growth from his students. There were plenty of other teachers in that school happy to teach “by the book.” Keating is a very different type of teacher, and I think he taught them that sometimes the road less travelled is always an option.

I’ll agree that that’s good, and it’s what’s so inspirational and memorable about him. But it’s only one element. Getting your students interested in learning isn’t the sole idea behind teaching.

Mr. Keating is a fantastic teacher because he emphasizes creativity and self-determination, which the students then apply to their study of poetry, and ultimately their lives. People complain about schools today not teaching students valuable or relevant life skills…school administrators could look to Mr. Keating as a shining example.

I highly disagree. Kids are creative and self-determined. Schools should not attempt to oppress that out of them by any means necessary but they should not have to establish a Kindergarten-environment for learning to counter psychological scarring from parents.

Schools are not there to do what Patents failed to do: give kids love and valuable life skills. Keating would have been a great father to any of the boys he “taught” but he neglected most of the teaching for parenting purposes.

@Phillis: I tend to agree with you, but I think in Matilda’s case, there was more than enough good reason for Miss Honey to step up like she did. Whether Matilda should have let the first kind adult she saw adopt her–that’s a whole other debate.

As for Keating’s students, I’m still on the fence about how much he should’ve influenced his students. I knew he would be a controversial choice though, and I’m prepared to live with that.

I had a teacher a bit like that at school who had a clear passion for English but was less passionate about the actual teaching part of the job.

He is a good teacher if you think about the environment in which he instructs.

Keating is dealing with a couple of things here. The institution itself is not one that promotes literature. The institution prepares young men for their futures and is probably more geared toward science and math as young boys typically do better in those subjects. Being an all boys school that prides itself on what becomes of their members and tradition literature while it would be required later in their lives is not a emphasis.

The second are the students. Some of them do not want to be in the school Some of the others do not take the class seriously. He remembers what his life was like when he went through the school and tries to appeal to the “catcher in the rye” boy than men of higher learning. By keeping things short and simple using different voices and introducing them to different environments around the campus he keeps them engaged in a subject most young men would rather just oblige and get through. He makes them think about the content of the words and how they effect them and others.

I would say his goal was to instill his love of the written word to his students, or at least, keep them from breaking to the schools will.

The lessons learned from a truly great teacher are those we never forget. I remember a particular English teacher I had who, after a play I had written, was mysteriously destroyed, presumably by a jealous classmate, encouraged me to rewrite it. The result was a second draft that was far better than the first. If it hadn’t been for that teacher, I may well have not bothered to try again. Thanks for your article, it was a fun read 🙂

John Keating was a narcissist whose message to impressionable teenage boys was not “Think for yourselves”, but “Think like me”. He was every bit as bad as the system he criticized.

All teachers are bad,its like looking for a good prison warder – some might be kinder than others,but at the end of the day they are their to lock the doors.

I take it you speak from experience, having suffered under all the world’s teachers and prison warders. I am glad to say I have been more fortunate: some excellent teachers, some hopeless cases, and not a single warder.

Most if not all of these teachers would be sacked and would deserve it. This list just shows how warped our culture’s notion of a ‘good’ teacher is, and how little attention non-teachers pay to the job content and responsibilities of the real thing.

Indeed, non-teachers have very little if any idea of what real teachers go through, and that goes double for Hollywood. That said, I’d be curious about your reasons why some of the teachers in the article should get fired (some reasons are obvious, but some not so much. For instance, why fire Miss Honey? Why Ms. Gruwell)?

These teachers are meant to be the best fictional creations, the best exemplars of certain recognisable types. But if you are referring primarily to Mr. Keating, then I agree. He´s a terrible idea of what good teaching is.

I’d go for Mr Casey, as played by Andrew Lincoln, in Teachers.

You missed the best ones — Will Hay (numerous films) and Alastair Sim as Miss Fritton (The Belles of St. Trinian’s).

My number 1 is Andrew Crocker-Harris from Rattigan’s The Browning Version.

My favorites are:

Herman Boone (Denzel Washington) – Remember The Titans

Ron Clark (Matthew Perry) – The Ron Clark Story

Katherine Ann Watson (Julia Roberts) – Mona Lisa Smile

Erin Gruwell (Hilary Swank) – Freedom Writers

Miss Stacy from Anne of Green Gables deserves a mention too. An inspirational maverick like all the best teachers.

Mr Chipping from Goodbye Mr Chips?

What about Jonathan Shale from The Substitute?

Great article.

Good post! In nonfiction/reality, I have great respect for various music teachers and their methods – notably Theodore Leschetizky, Nadia Boulanger, and Marcel Tabuteau. The oboist Tabuteau is legendary, and is described in Laila Storch’s excellent book and then expounded upon in David McGill’s. He’s one of the few music teachers I’ve yet seen who approached phrasing with such particular catholicity.

And by the evidence of his writings, the physicist Richard Feynman must also have been an incredible teacher. I’m no maths/physics geek, but even I got through QED with a complete (though sadly not lasting) understanding of what he said.

Mr Keating threw out tradition, ripped up orthodoxy and acted against the curriculum he was hired to teach.

This behavior, and his vague concepts of liberty, rebellion and progressivism directly led to the suicide of one of his students. He played with fire and the minds of impressionable adolescents and destroyed lives.

And I respect that opinion. In fact, I was leaning toward it at one point while writing this. But I chose to write about Keating because (A), he is controversial. He’s not by any means a saint, and Hollywood sometimes goes too far in painting teachers as perfect. (B) and more importantly, it could be argued that since Keating’s students had no concept of self-determination that we know of, they had to start somewhere. Were Keating’s methods unhealthy and perhaps dangerous? Arguably yes. But did he leave a good impact? Perhaps, for some. (In retrospect, maybe he was more of an in-between? Maybe the English teacher version of Snape, sans the bitterness and sarcasm)?

He’s inspiring, which is half the battle for a high-school teacher.

We’ve probably all had teachers who did all sorts of solid teaching, but for whom we mostly remember one or two remarkable moments.

Miss Honey from Matilda! <3

What about Mr Miyagi? He takes the somewhat weedy and newly transplanted from New Jersey to California Daniel LeRusso and turns him into a karate champ?

What about Robert Donat’s Mr Chips? “Give a boy a sense of humour and a sense of proportion…” Best advice you could give any student!

A great discussion, and regardless of best or least it is indeed true that teachers have a massive influence on our lives. Even in traditional literature the interaction of the mentor is a fundamental rite of passage. In many ways this alludes back to our community lifestyles where the parents were important, but children were often raised by elders or leaders. The role of a teacher is one that we should place greater importance on in society, and Western society especially has lost track of this. Thank you for sharing a great thought (and memory) provoking article.

I remembered my teacher in literature. So much lessons learned from her.

Having taught now for more than three decades, I always wonder how I’m remembered by former students well after they finished their school years. There is truth in learning from bad teachers–I remembered them and hoped I avoided what I did not like about them.

Don’t forget Remeber the Titans, Coach Carter and To Sir With Love.

Here’s a ‘good’ teacher, part-fiction, part-fact: “Since it is so likely that children will meet cruel enemies, let them at least have heard of brave knights and heroic courage.” – C. S. Lewis, author of the Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (and others).

Fact because this is a real human being from the last century. Fiction because by far his biggest influence on the world, and in particular the world of children, is exerted in countless ways, each day, as new kids discover the chronicles of Narnia.

Two corollary points to make. Firstly, is there any real difference between fictional and historical, when it comes to the characters? Today’s biography is tomorrow’s mythology. Secondly, is it meaningful to refer to a literary character as a “teacher” if they’re not shown teaching anything?

I think you should identify the actors playing the roles mentioned in the text. The face is not that of a personage but a person …both should be known…

I enjoyed reading about both good and bad teachers. I do agree that Severus Snape is a tricky one to place, because there are so many different points of view one can take on him.

Would you please explain more what you meant by Umbridge being “personal”? I believe the point you’re trying to make is that she uses personal means, such as blood, to punish, and that it is her own fear for loss of control that causes her to be such a bad person?

Overall, I loved reading the article!

Great article! Props to the depth of all the examples that you covered, well done.

The Dead Poet Society was used as an example of how not to teach children with additional needs when I was on my PGCE. I refer to the scene when a boy, clearly struggling, was singled out and more or less mocked, abet in a ‘loving’ Hollywood way.

I agree with all of your points. Some teachers can be good and others not great, but they all end up shaping a little bit of who we are.

great, you have delivered a great lesson to people. teacher is great man in the world

This is a great article. Beautifully written. I couldn’t agree more with all of the examples and in-depth explanations.

There is another set of instructors who come to my mind. Protagonist and antagonist. I always think of The Karate Kid’s Mr. Miyagi and Cobra Kai sensei, John Kreese. Both teach the same discipline to students of the same age. Yet the lessons underlying their instruction are painfully obvious as they are manifested in pupils, Daniel and Johnny. One learns self respect and discipline while the other learns hatred and ruthlessness.

You hit the nail on the head! I think it’s so important to represent both good and bad teachers in media so that kids have an idea of what is acceptable–sure, the bad is often exaggerated, but anyone can be that great a teacher if they try!

I really enjoyed reading this article! I had a high school teacher who was just as mean and manipulative as Umbridge. As a beginning teacher, this made me reflect on my own practices and think about what I can do to avoid being like her.

Nice exploration of these characters, and good choices. Reading through this article got me thinking about some of my favorite fictional teachers.

One that came to mind for the “good teacher” category: Prez from HBO’s The Wire. He’s the kind of teacher who has no truck with “teaching to the test,” and who goes the extra mile with his students, stimulating their learning by building the class curriculum around his students’ unique interests.

For “In Between”: Dewey Finn from School of Rock. Definitely a shady character who lies his way into a lucrative teaching job that should belong to his friend, and which he is grossly unqualified for. However, like Mr. Keating, he ends up providing his students with a unique and rewarding creative outlet that was otherwise lacking in their lives before he showed up. Even if his motives and execution were selfish and questionable, I still think he did more good than harm.

For “Bad Teacher”: Kenny Powers from HBO’s Eastbound & Down. This rude, crude, ex-major-league-baseball-player-turned- PE Teacher basically has zero redeeming qualities when it comes to teaching. His methods are as horrifying as they are hilarious.

Interesting that Snape has this kind of a kaleidoscope of a personality.

Love the section on Keating. Also one of my favorite fictional teachers.