Genkaku Azuma: Anatomy of a Tragic Villain

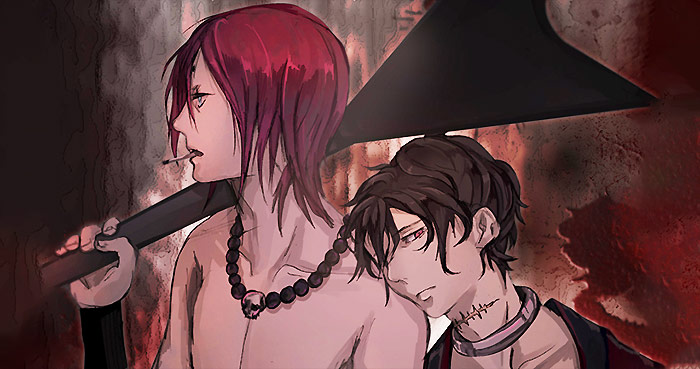

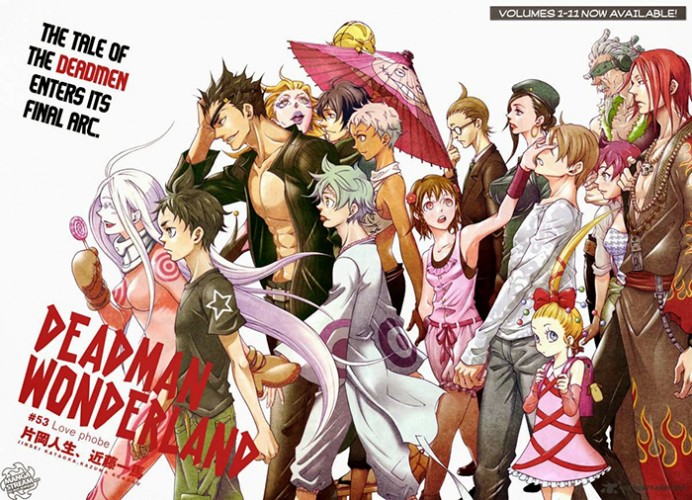

The ultraviolent horror anime Deadman Wonderland possesses a fascinating cast of characters. The men and women of this series are exciting, colorful, diverse, and a lot of fun to watch–particularly since none of them are quite who they seem to be at first. However, the one character who stands out above all the others is the villain known as Genkaku Azuma, the leader of the Undertakers, Deadman Wonderland’s secret police. Being one of the main antagonists of the anime–and the first major arc of the manga–he manages to be not only threatening and sympathetic, but also tragic. Indeed, few other villains in any series manage to embody tragedy quite as well as he does. The tragic aspects of his character arc come through not just in his sad backstory, but in everything that happens to him and every choice he makes throughout the course of the series.

What Is “Tragedy?”

Although many people in online fan communities use “tragic” and “sympathetic” almost interchangeably, these words do not mean the same thing. Many anime characters–villains or otherwise–are sympathetic without being tragic. In literary terms, “tragedy” refers to something very specific: namely, a story intended to produce strong emotions by showcasing the downfall of a great yet flawed human being 2. Traditionally, tragedies were theatrical productions, the most famous of which were written by ancient Greek poets or the Renaissance playwright William Shakespeare, but tragedy appears in other media as well.

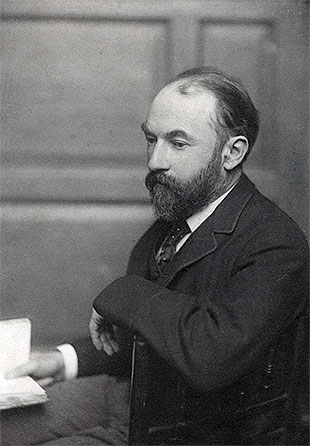

The Victorian author Thomas Hardy was well-known for his tragic novels. Hardy’s tragedies are unique in that the central characters are not born into high social status, although some (like Michael Henchard in The Mayor of Casterbridge) acquire prestige later in life. Although Hardy’s characters are not high-born, they possess real passions and drive that cause the audience to identify with and root for them, and create genuine emotional pain when their missions inevitably fail. An essay on Thomas Hardy’s tragic heroes describes them thusly:

If Hardy created anything he created souls capable of great feeling, souls capable of exaltation. […] Because of the very strength of their passions Hardy’s characters demand our sympathy, and we experience a feeling that someone of great worth has been lost when we see them destroyed.

[…]

The ill fortune that befalls a tragic hero is the result not only of forces working against him from without but of forces within him that hasten him towards his downfall. Aristotle tells us that the tragic hero is not preeminently virtuous but must make some error of judgement. 3

What all this means is that truly tragic characters are, at least in part, responsible for their own suffering, and contribute to their own downfall by the choices they make. A character who simply suffers and lashes out in reaction to that suffering without making a conscious decision cannot be truly tragic no matter how sympathetic they are. The Wretched Egg, another Deadman Wonderland antagonist, may invoke sympathy and pity from the audience. However, she cannot be tragic in the truest sense of the word because she never had a choice about whether or not to be a villain. Genkaku, by contrast, made the conscious decision to become a villain, and could have averted his sad fate if he had made better decisions.

Cry For The (Literal) Devil

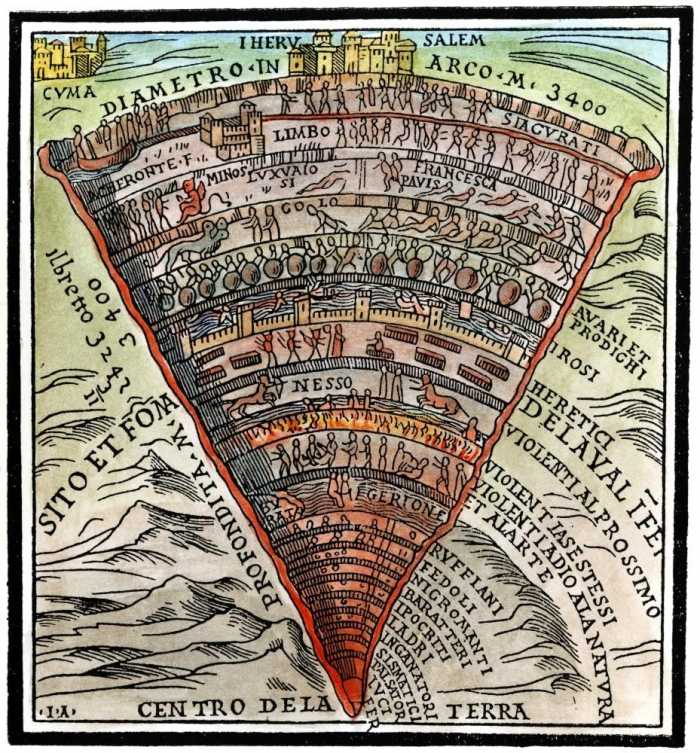

One subtle way in which the series hints at Genkaku’s tragic status is to portray him as a Satanic figure. Deadman Wonderland, the prison in which the series takes place, is repeatedly referred to as hell, often explicitly, by the other characters. G-Block, where the Deadmen live, is a particularly obvious symbol of hell because it’s literally underground. At the bottom of G-Block live the Undertakers, Genkaku included, in much the same way that Satan lives at the bottom of hell in Dante’s Inferno 4.

Genkaku certainly looks the part of the Devil, with his bright red hair, pale skin, black robes that have a flame motif, skull necklace, and fondness for heavy metal music–a genre that frequently uses images of devils, demons, and hell. In the manga, though not the anime, he also has red eyes. Even his name carries Satanic connotations, since just one minor syllable change converts his surname, Azuma, into “Akuma”–the Japanese word for “devil 5.” In traditional Christian lore, Satan was once a mighty angel named Lucifer, who was cast out of heaven for rebelling against God 6. In the context of Deadman Wonderland, Genkaku could himself be seen as a “fallen angel” of a sort.

Both Lucifer and the tragic heroes of Ancient Greece suffered from hubris, or excessive pride, particularly in defiance of a god or gods 7. Genkaku seems to posses hubris as well, since he believes that he has the right to make value judgments about who lives and who dies, and whether someone’s death is ultimately good for them. Even as a teenager, he showed signs of thinking he was better than other people, particularly the other monks at the Buddhist temple who abused him. When his master, the head monk, questioned him about them, he claimed to have compassion for his abusers, only to state, in practically the very next breath, that, “they blindly sow evil” and refer to them as “those who resist enlightenment.” Later, when he kills them, he claims that he has “saved them […] from evil.”

A Master Of Deception

Although virtually all the characters in Deadman Wonderland possess dark secrets and hidden depths, Genkaku is one of the toughest to pin down. When first introduced he comes across as a hyperactive, easily-distracted, gleefully-sadistic thug, but this is a carefully constructed ruse. Although he seems happy and enthusiastic in the beginning, by the end he reveals himself to be suicidally depressed and carrying around years’ worth of pain and loneliness. Even the ridiculous surfer-dude accent he affects in the anime’s English dub falls away in the last episode once his true motives become clear. If his backstory is any indication, he has been putting on performances for other people ever since he was young.

Interestingly, he seems to be as much of an enigma out of universe as he is in-universe. Fanfics that portray him accurately are very hard to find, and even the best of them rarely capture more than one side of his personality. The best way to get a complete sense of his character, then, is to start in the very last scene he appears in and work backwards, interpreting all his actions and dialogue in the context of that final scene. Even his backstory, illuminating as it is, leaves unanswered questions that are only addressed in the last couple of speeches he makes before his defeat.

Genkaku’s Mission In Life

Much like the Buddhist religion he grew up around, Genkaku’s ultimate aim is to free people from suffering. Unfortunately, he believes that death is the end of suffering and, as a consequence, the best way to save people from suffering is to brutally murder them. He is, in effect, a suicidally-depressed person who takes out his inner demons on other people rather than himself, something he even admits openly toward the end of the anime:

These are your only options: live with the fear, embrace the insanity and all the darkness it brings–or shed the yoke of this world in death! Just think how lucky you are that I’m here, the one who’s gonna set you free! 8

By the same token, Genkaku has trouble understanding why the other characters cling to life and hope in the face of so much pain and misery. Although at one point he calls himself a “jealous psychopath”–likely to throw the other characters off balance–it’s clear he doesn’t see himself as the villain. From his perspective everything he does is in his victims’ best interests, and when the heroes don’t accept his attempts to release them from suffering he seems genuinely frustrated and hurt. He tells them: “Releasing my fellows from the bonds of fear and oppression, from the shame of betrayal–I’m a saint, man!” The word “saint” is particularly interesting because in common speech it usually refers to someone who endures suffering quietly for some noble or higher purpose. The point Genkaku seems to be making is that he could have killed himself at any time, but instead he selflessly continues to live and suffer just so that he can save others from their suffering instead.

At the same time, there is some indication that he does question the morality of some of the choices he’s made, even if he can’t openly acknowledge as much. When he tries to explain his motives to others, his voice takes on a distinctly angry and defensive tone that other villains who are truly oblivious to the harm they are causing–like Mao from Code Geass or Bondrewd from Made in Abyss–conspicuously lack. These more oblivious villains may still get angry when their plans are thwarted, but they don’t mind being accused of moral missteps because they don’t see their actions as morally wrong at all. By contrast, Genkaku, particularly in the anime, seems to harbor some awareness of why the other characters would view his actions as morally reprehensible. He still sees himself as a good guy, but he expends a lot more time and energy trying to convince the other characters, particularly Nagi, that his decisions are the right ones. When Nagi rejects his worldview for good and all, Genkaku gets so angry that he blows a hole through Nagi’s stomach with a machine gun!

The political commentator Jonah Goldberg writes in his book Suicide of the West:

Of course, all other things being equal, people want to be rich rather than poor. But what they want even more is to be admired, respected, and valued. […]

A desire to be admired is hardwired into us, just as it is in chimpanzees. 9

As such, Genkaku is not only convinced of his own righteousness but deeply invested in the image of himself as a good person, a fact that impacts everything about how he behaves throughout the series. At the same time, he possesses enough self-awareness to know that not everyone sees him that way. Such a mentality is understandable enough, considering how in his youth, the one thing he could trade on was his moral superiority to those surrounding him.

An In-Depth Look At Genkaku’s Past

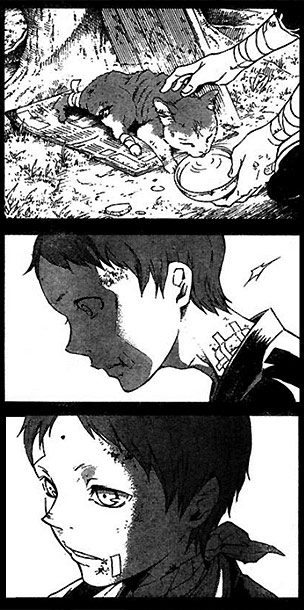

When Genkaku was a boy, he spent much of his time training to be a monk at a Buddhist temple. Unfortunately, he suffered vicious abuse–including sexual abuse–at the hands of the other monks-in-training. His master, the head monk, ought to have been aware that something was wrong, as Genkaku would show up before him covered in bandages. However, rather than attempt to figure out what the problem was, the head monk seemed to assume that Genkaku was responsible, as he once chided him: “Violence begets violence, my son.” When Genkaku was about sixteen, a massive earthquake known as the Red Hole destroyed the temple and trapped all the monks-in-training except Genkaku under rubble. Genkaku subsequently murdered the other monks-in-training and created an effigy of their corpses, mounting them on a wall that he painted with their blood.

One thing that stands out immediately about Genkaku’s backstory is how lonely he seems. His parents are never mentioned, his peers bully and abuse him constantly, and the person who seems as though he should be responsible for his well-being does nothing to protect him. His only friend is a mangy stray cat, but the cat ends up dying during the Red Hole. The loneliness he experiences dovetails perfectly with Deadman Wonderland‘s overarching message, that people need like-minded sympathizers to help them through hard times. In the anime’s ending credits, Genkaku is one of only two characters who is shown alone, the other being his fellow villain Tamaki. The audience is left to wonder what would have happened if even one person had been there to stick up for Genkaku or protect him from his abusers.

This setup is already quite depressing in and of itself, but the anime twists the knife in even further than the manga by changing the meaning and context of some of Genkaku’s philosophical musings. In the manga, after Genkaku discusses the latest round of abuse with his master, he asks his master if it’s possible to “save” his abusers somehow. The scene then abruptly cuts to the day of the Red Hole, with Genkaku musing about how the Buddha could have known that death was suffering without having experience it himself. In the anime, by contrast, Genkaku poses the following question: “Is death suffering? And, with respect, if so, how could the Buddha have known it to be suffering?[emphasis added]” The way this question is worded makes it seem like part of a longer conversation Genkaku had with his master, rather than his own personal thoughts. If this is indeed the case, then the head monk would have had even more reason to think that something was wrong with Genkaku. If only he had conducted an investigation into why this teenage boy was appearing before him with broken bones and asking him whether death was really suffering after all, perhaps he could have put an end to his downward spiral then and there. Yet, he did nothing.

The series never reveals what Genkaku did between the events of his backstory and the events of the series proper. One bonus panel at the end of Volume 12 suggests that he spent some time in a regular jail before being transferred to Deadman Wonderland, but how he got there is never explained. Japanese jails are notoriously brutal and austere institutions, and prisoners who have been to jail in both the United States and Japan say that Japanese jails make American ones seem like nothing in comparison 10. When Genkaku first murders his abusers it’s open to interpretation whether he really thinks he’s saving them, or whether he just kills them in vengeance and claims to have “saved” them as an excuse. If there was ever any doubt in his mind, a stint in jail could have easily led him to embrace the notion that everyone would be better off dead.

The really sad thing about Genkaku’s backstory is that it didn’t have to be this way. Of course, many anime villains who suffered abuse in the past have a moment where they snap and kill their abusers, but most of them do so in self-defense. By contrast, Genkaku murdered his abusers in cold blood, in an extremely gruesome and over-the-top manner, when they were already incapacitated and unable to hurt him. If he had simply walked away and left them to their fate, they might have still died and he would be innocent of any major crime.

Genkaku’s Quest to “Make” Nagi

In “Vermilion,” a song by the famous Midwestern metal band Slipknot, a lonely man tries to comfort himself by inventing someone to love. He invests a tremendous amount of time and energy into envisioning his perfect partner. Unfortunately, this exercise brings him no happiness because there is nothing he can do to make his imaginary lover real 11. Genkaku’s obsession with the Deadman known as Nagi Kengamine follows a similar pattern, with Genkaku attempting–unsuccessfully, in the end–to turn Nagi into the kind of person he wishes him to be. It’s interesting to note that the word “vermilion” literally refers to a brilliant shade of red–a color commonly associated with Deadman Wonderland, and Genkaku especially.

Two years prior to the events of the series, Nagi deliberately lost a round of Carnival Corpse, the gladiator-style game Deadmen are forced to play, in order to protect his pregnant wife. Unfortunately, the rulers of Deadman Wonderland determined that she still had to pay a penalty, and when she tried to escape, Genkaku murdered her. Sometime later Nagi brutally slaughtered a swathe of Genkaku’s henchmen in retaliation. Ever since that time, Genkaku has been obsessed with converting Nagi to the Undertakers’ side. When Nagi forms a team of resistance fighters called Scar Chain, the Undertakers have a perfect excuse to capture him.

It’s important to note that Genkaku seems to be attracted to Nagi’s powers first and foremost. There is no credible evidence, for instance, that he murdered Nagi’s wife out of jealousy, as some fans allege, or even that he would have any interest in Nagi were the latter not so powerful. Although Nagi looks delicate and weak, his ability to turn his blood into bombs makes him one of the most inherently dangerous Deadmen. Moreover, it’s not hard to imagine that Genkaku, whose ultimate mission involves killing people, would want a power like that for himself. Although Genkaku manages to be one of the deadliest characters in the series even without superpowers, a Deadman like Nagi can still kill people far more quickly and efficiently than Genkaku himself could ever dream of. Because Genkaku has no hope of obtaining those powers on his own, the only way for him to leverage Nagi’s powers for his own ends is to get Nagi on his side. To really drive the point home, in the anime he openly tells Nagi that “[I] don’t so much wanna have you as be you.”

Still, Genkaku likely has an ulterior motive for pursuing Nagi that goes beyond a simple desire for more power. Simply put, he has every reason to think that he and Nagi are a lot alike. Both started off as decent people despite their rather miserable circumstances, only to turn murderous after the one they most cared about died. In the manga, Genkaku goes so far as to confess to Nagi that he had seen him as a manifestation of his own anger. What bolsters Genkaku’s opinion of Nagi still further is, in all likelihood, a desire to find someone who could truly relate to him. Although he’s the leader of the Undertakers and has a good relationship with at least the other captains of the force, he otherwise doesn’t have much in common with them and can’t really connect with them on a deeper level. In this context, Genkaku attempts to transform Nagi into the perfect killer under the assumption that Nagi can learn to see things from his perspective. Ultimately, like Pygmalion from the famous Greek myth 12, he ends up falling in love with the monster that Nagi could become.

The problem, of course, is that Nagi has a mind of his own. Despite Genkaku’s best efforts, eventually Nagi’s friends convince him to reject Genkaku’s nihilism, and then Nagi turns his back on everything Genkaku stands for. No wonder Genkaku gets so angry at him. Still, to his credit, Genkaku seems to have made some sort of connection to Nagi, since the latter says to him, somewhat apologetically, “I’m sorry my friend, but I’m afraid you’ve overestimated me.” It doesn’t make sense that Nagi would call Genkaku his “friend,” or have any particular sympathy for him at all, unless he understood where Genkaku was coming from and related to him on some level. The implication, in other words, is that Nagi shares Genkaku’s worldview to at least some extent.

This attitude also goes a long way toward explaining Genkaku’s otherwise strange behavior at the end of his character arc. Despite openly stating that he wishes to die, he becomes genuinely afraid when Ganta gets ready to kill him, and–in the manga–even ponders running away. However, when he notices that Nagi has grabbed onto his sleeve, he accepts his fate with a smile. This seemingly contradictory behavior makes sense when one considers that what Genkaku really wanted was not simply death, but death at the hands of someone who cares for him. Since Nagi is now mortally wounded, Genkaku has the chance to die alongside him and not be lonely anymore. Nagi’s rationale is particularly suggestive: “That’s right my friend, we’re in this together.” After all these years, Genkaku has finally found someone who can understand him and share in his misery–but only when it’s much too late to do any good.

Why Did Genkaku Kill Nagi’s Wife?

The answer to the question of why Genkaku killed Nagi’s wife may seem obvious, but is in reality fairly complex. Typically, the act of murdering a heavily-pregnant woman and preserving her unborn child in a jar would be so heinous as to be impossible to defend. However, Deadman Wonderland is anything but a typical series, and Genkaku does have extenuating circumstances that make his decision more understandable, if not necessarily forgivable.

The most obvious reason why Genkaku would murder Nagi’s wife is to free her from suffering–his ultimate end goal for killing in general. Furthermore, in this one instance, such a motive does not come about solely as a result of his warped worldview, but actually reflects the reality on the ground. The world in which Nagi and the rest of the Deadmen live would be about the worst place imaginable for a pregnant woman or a young child. Even if Nagi was willing to throw a match to protect his wife, there is no guarantee that the other Deadmen–who risk their own limbs and organs every time they fight a match–would be so merciful. Furthermore, there might not have even been a safe place for Nagi’s wife to give birth, as it’s doubtful a prison like Deadman Wonderland would have any place for a labor and delivery unit. Tamaki does imply that he wanted to keep Nagi’s child alive to see what happened when a pair of Deadmen reproduced. However, had the child survived, in all likelihood, she would have been taken away from her parents at a relatively young age to be experimented on. Genkaku may well have thought that, by killing Nagi’s wife and child early, he was saving them and Nagi himself from worse pain later on.

Genkaku has his own reputation to worry about as well. As the leader of the Undertakers, his entire job revolves around corralling and ensuring compliance from a group of superhumans with a whole range of deadly abilities–to say nothing of his own men, who according to Nagi are the worst sorts of criminals imaginable. Genkaku also has to answer to Tamaki, who is in charge of managing Deadman Wonderland’s day-to-day affairs and is even more ruthless and heartless than Genkaku himself. As such, Genkaku really can’t afford to show weakness or mercy, because if he did so he would at best lose authority and credibility and at worst be removed from power and–most likely–killed. An easy way to assert his own ruthlessness and dominance would be to present himself as the sort of man who would murder a pregnant woman for fun–or in cold blood to make a point–regardless of his own feelings on the matter.

As such, this situation highlights yet another depressing aspect of Genkaku’s predicament. At the end of the day, Genkaku is a prisoner–a very powerful and dangerous prisoner, to be sure, but a prisoner nonetheless. His entire life revolves around keeping the prison’s engine of cruelty and dehumanization running smoothly. To make matters worse, he has essentially no options for either escaping or being promoted to a different position further removed from the carnage. He has every reason to think that he will be stuck there, performing the same murderous work, until he dies.

Genkaku’s Relationship To The Other Undertakers

Towards the end of the anime, Genkaku, in a fit of rage, kills nearly all of the Undertakers, sparing only his sidekick Hibana. Fans have sometimes debated whether he missed Hibana on purpose, or simply forgot that she was there. Interestingly, in the anime, Genkaku spares not only Hibana but the other Deadmen who are in the room with him. Rather than kill them right away, he instead proceeds to explain his worldview to them, as if hoping that they will understand. The implication seems to be that he really did want the other Undertakers dead, except for Hibana.

If Genkaku truly sees himself as a good person, then his reason for hating the other Undertakers is pretty obvious. As Nagi points out, the Undertakers comprise the worst and most irredeemable criminals in Deadman Wonderland. What, after all, must it be like to be their leader? What must it be like for someone who truly believes that he is a good person who does the right thing to have to spend hours every day with hoardes of psychopathic criminals? The other captains, at least, are young people who kill because it’s the only thing they’ve ever known; but many of their henchmen might simply kill and torture people because they enjoy it. Some of them might even be rapists–and Genkaku knows what it’s like to be raped.

By all appearances, although Genkaku is very effective at his job, he does not enjoy it very much. In order to end suffering, he finds himself trapped in a place where everyone is constantly either suffering or making other people suffer–often with his explicit involvement. At the same time, his own actions are what brought him to this point. He could have avoided all this simply by choosing a different path.

Is Genkaku A Great Man?

Traditionally, tragic heroes were singled out as “great men”, who were somehow more special than ordinary human beings. In ancient Greek tragedies and Shakespeare plays, they were usually kings, princes, or famous warriors. In more modern stories, which focus more on common people, tragic characters still have qualities that set them apart from the people they interacted with. The fact that Genkaku is not the central character in Deadman Wonderland makes it harder to discern whether he possesses a sense of “greatness.” However, both the anime and, to a lesser extent, the manga, contain several clues that he could be considered great, in his own way.

One can’t help but wonder, as one watches Deadman Wonderland, what Genkaku might have done with his life if he hadn’t gone evil. All the evidence suggests that he would have been capable of great things no matter what he did. He’s a charismatic leader who keeps command, somehow, of the worst and most dangerous criminals in the prison, while also suppressing suicidal levels of depression and rage. His genuine enthusiasm for whatever he’s doing is one of the few aspects of his character that he isn’t trying to hide. Even in his flashback, where he’s trying to be stoic, aspects of this enthusiasm come through. For instance, when he eventually commits murder, he doesn’t simply stab his victims to death and then walk away; he actually dismembers them and decorates a wall with their blood and bodies! Imagine if he applied that sort of commitment to something constructive!

Furthermore, while he often acts silly, he is in reality extremely intelligent. He manipulates Nagi, the other Undertakers, and possibly even Tamaki to his own ends, and very nearly succeeds in turning Nagi into the monster he insists he is. In the anime he also deduces, without much effort, that Karako is in love with Nagi. When he eventually stabs Karako, he points out that her injury wasn’t fatal–suggesting that he can tell, practically at a glance, the difference between a fatal and a nonfatal wound!

Another subtle clue as to his greatness stems from his height. Visual media, like graphic novels and animated series, frequently use height as a marker of status, and a piece of art featuring the entire manga cast shows that Genkaku is taller than every other character except for the Deadman known as Idaki Hitara. Since Hitara doesn’t appear in the anime at all, and has a fairly minor role even in the manga, Genkaku ends up being the tallest character fans see much of by default.

It should come as no surprise that fangirls enjoy writing stories in which he is somehow redeemed by the power of love. These stories assume that with the right sort of partner, he could end his pain and revert to the gentle, caring individual he used to be. The problem is that, for all intents and purposes, this gentle individual no longer exists. The Deadman Senji hints at this when, in a conversation with Ganta, he warns Ganta that “Once the old you’s dead and gone you have to own up to whatever takes its place.” Whatever options Genkaku may have once had for escaping a life of crime are long gone, and so all the audience can do is wonder what could have been.

In sum, Genkaku Azuma is a remarkably tragic villain–arguably one of the most tragic villains ever to appear in an anime series. He may be a vicious murderer, but he’s also a lost soul suffering nearly unendurable levels of pain and thoroughly convinced of his own righteousness. What’s even more remarkable is that the creators of Deadman Wonderland never set out to write a tragedy. Genkaku isn’t the main character of Deadman Wonderland–that honor belongs to the plucky young Deadman known as Ganta. In fact, he isn’t even the main villain, and only in the anime could he be considered a central antagonist of any sort! All the same, as he goes, so too goes Deadman Wonderland‘s storyline. He is single-handedly responsible for taking an ultraviolent horror story that had been vapid and predictable, and transforming it into something much deeper and richer.

Works Cited

- Featured image by Pastenaga. ↩

- “Tragedy.” Literary Terms, 1 June 2015, https://literaryterms.net/tragedy/ ↩

- Spivey, Ted R. “Thomas Hardy’s Tragic Hero.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 9, no. 3, December 1954, pp. 179-191, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.rit.edu/stable/3044306?seq=6#metadata_info_tab_contents ↩

- Burgess, Adam. “A Guide to Dante’s 9 Circles of Hell.” ThoughtCo, 1 November 2019, https://www.thoughtco.com/dantes-9-circles-of-hell-741539 ↩

- “Akuma (folklore).” Wikipedia, The Wikimedia Foundation, 13 September 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akuma_(folklore) ↩

- Rhodes, Ron. “How Did Lucifer Fall and Become Satan?” Christianity.com, https://www.christianity.com/theology/theological-faq/how-did-lucifer-fall-and-become-satan-11557519.html ↩

- Roberts, CJD. “Hubris (or Hybris)” Ancient Greek Theatre, November 2014, http://theatreofancientgreece.blogspot.com/2014/11/hubris-or-hybris.html ↩

- “Grateful Dead.” Deadman Wonderland, written by J Michael Tatum and Patrick Seitz, directed by Joel McDonald, Funimation, 2012 ↩

- Goldberg, Jonah. “Human Nature.” Suicide of the West, New York, NY, Crown Forum, 2018 ↩

- gaijinass. “Brutal Realities about Prison in Japan.” Gaijinass, 2017, https://gaijinass.com/2017/03/30/brutal-realities-of-prison-in-japan/ ↩

- Slipknot. “Vermilion.” Vol. 3 (The Subliminal Verses), Roadrunner Records, 2004 ↩

- Jargalsaikhan, Bolor. “Story of Pygmalion and Galatea by Sir Edward Burne-Jones.” Daily Art Magazine, 12 December 2017, https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/story-of-pygmalion-and-galatea/ ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Deadman Wonderland chose to compromise its artistic potential for the sake of appealing to a power-hungry, adolescent audience. It had all the potential, as outlined in this article very well, but ultimately failed to deliver.

This character was memorable but the anime felt like a total copy paste of other shows.

Genkaku is freaking amazing. Love the character but he has a twisted view of the world.

I think Genkaku actually has a thing for Nagi, but you know, there’s no definite answer given all the insanity. Genkaku could just really, really want to kill Owl.

The problem with Deadman Wonderland is that it’s just too short. It’s just a window into the world of this story, and there’s rarely enough background to any of the characters, none of the plot lines are sufficiently developed, and some plot threads are just left hanging, or forgotten completely. The show should have been twice the length.

I love him. I mean his weapon is a gun guitar for crying out loud.

This show reminded me so much of Eureka Seven.

Enjoying reading your article. Which are some other villains you would say have interesting and complex backstories?

Lady Eboshi from Princess Mononoke, very human and a very interesting part/side antagonist (but not really a villain).

Kotomine Kirei. Him being a villain comes out of left field towards the end and in some circumstances, he even works with Shiro. He has his own set of morals that aren’t nessisarily good or evil, just what he believes to be right. He’s a pretty interesting character.

Deishu Kaiki. I really like his way of talking and how he has that “gloomy” aura around him. Although he didn’t have too much screen time, he has done enough for me to consider him as an interesting villain.

The villain from Higurashi. I won’t say who it is, as it would give away half the tension in the show, but the villain is one of the most interesting, complex, and REAL villains I have ever seen.

I don’t know if others would consider him a villain, but i think “Kaiki” from Nisemonogatari is a very interesting villian, besides that he is from the monogatari series.

The Count of Monte Cristo from Gankutsuou. Although, arguably, he could be viewed as a wronged hero getting well-deserved revenge.

The anime portrays the count in a much more antagonistic view compared to the novel. Give the book a read, the expanded view from Dante’s perspective as the protagonist makes him much more sympathetic and, more importantly, human to the reader.

Makashima Shogo. He believes that the Sybil system of Psycho-Pass is oppressive and enslaves the people. He wants the people of Japan to be free to express their souls without having a computer overlord decide everyone’s fate. He is one of the best villains in my opinion because in a traditional story he’d be the hero. The world of Psycho-Pass is basically 1984, but if the government was actually good.

To me, what makes him the best is the fact that he’s so good at twisting words that he even manages to convince a large number of viewers that he’s right.

Johann Liebert from Monster for sure.

Hisoka from Hunter X Hunter, easy choice.

Hisoka can be a nightmare of shonen anime fans, he’s creepy as hell… at a respectable level.

Sometime I wonder if he has a next level ability something like Biscuit or Pitou where he unleash his power from his crotch.

Completely agree! Not only are you left to question his mentality, but also his sexuality. Sometimes he’s the villain, sometimes the hero, and other times just plain crazy. Love him <3

Kumagawa Misogi from Medaka Box. Dude has one of the most OP abilities in fiction, is mentally unhinged as fuck, and you can’t help but rooting for him because all he wants to do is prove he can beat the main characters because all he ever does is lose at everything he tries. He’s the type to be comedy relief one second, and be an imposing big bad evil guy the next. One scene he’s trying to get female characters to wear naked aprons, the next he’s killing an entire slew of side characters.

I’d have to say Yagami Light from Death Note is one of my favorite ‘villains’. His plans and execution of plans was flawless, and although he wasn’t a ‘villain’, I still think of of him as one, because of the motives behind his actions.

I believe the term for that would be antihero.

Orihara Izaya from Durarara.

Isabella from the Promised Neverland is the first one to come to mind. She has a lot of presence, a tragic backstory, and the fact that she’s basically an older, more experienced, jaded version of the protagonist makes her a threatening intellectual opponent – she knows exactly what it’s like to be in the protagonist’s position.

The Rail tracer from Bacccano! He was more of a sociopathic antihero but it’s a blurry line.

Ozu from The Tatami Galaxy was fantastic in this role. Such a fantastic show.

Definitely Doflamingo I loved his character, his design and his backstory. He is easily one of the coolest looking One Piece villains and easily one of my favourite anime villains of all time.

I liked the villains in Shin Mazinger, specifically Baron Ashura.

Not as individuals, but I rather like the trio of The Major, Father Anderson, and Alucard in Hellsing Ultimate.

All villains in their own ways, and the writer plays them against each other.

Treize Khushrenada from Gundam Wing.

Man, I’ve seen this anime 3 times and it’s still amazing. The manga is amazing as well, and I think the judgement placed on the anime for its length and abrupt stop – some calling it merely a prologue to the manga – is misplaced and unfair.

For a short term character, Genkaku was pretty awesome.

He is my favorite character from the entire anime.

You should absolutely do yourself a favor and enjoy the Deadman Wonderland Manga. The anime ending certainly isn’t as bad as some make it out to be, but it was clearly meant to continue on.

Honestly, I’ve read the manga now multiple times. I still think that the anime handles things better (Genkaku in particular).

This article does justice to my fav antagonist Genkaku! Thanks for all the memories.

I feel a lot of the characters are interesting and unique in their own dark and twisted manner. I feel if the show was longer the character could develop to be even stronger.

For other characters, yes, but for Genkaku not so much. His and Nagi’s character arcs are pretty much the only ones that the anime gets around to covering in their entirety, so we don’t see much more of them in the original manga (and what is in the manga isn’t quite as impressive). To explore Genkaku’s characterization even further you would pretty much have to tell the whole story, beginning to end, from his perspective IMO.

This anime has a way of bringing out some of the biggest feelings. Hope, despair, pain.

He is in my top 10 anime villains.

It really piss me off when a manga doesn´t know when to end, so I was really pleased when the manga ended. For me, there was no need in showing us “and they lived happily ever after”, though I´m glad they both survived. Besides, I don´t consider this manga to be a shounen, it has too much gore and psychological issues involved, like Tokyo Ghoul: re has, for example. I almost can´t handle Shiro´s past. I had nightmares with it.

I’m up to volume four of DMW. The brief glimpse of Genkaku’s background really added something intricate to him that made me reflect on who he was.

Uber Monk? What in the world…

Thought this was the best tv show ever, until half way through the season. It became super rushed. I found myself staring at my phone hoping to get notifications from my friends replies in messages.

The anti characters are well established, otherwise most are dumb like they can’t think alone.

I wanted to love Deadman Wonderland and be a raging fanboy about it, but I can’t because of it’s many shortcomings. BUT I love Genkaku so it has that going.

I don’t know but I think that Genkaku has some type of feelings for Nagi.

This manga is worth reading. The anime is watchable too.

I was really looking forward to Deadman Wonderland when it came out because I liked it’s concept and style story-wise, it had a really good premise, but I feel like it wasn’t as interesting as it could have been.

This show is kind of a wild ride from what the heck are they dumb or something, to this anime is horrible.

The characters have goals and unique characters. I recommend the manga to newcomers of this.

The anime is essentially a great pathway to the manga.

I was truly anticipating Deadman Wonderland when it came out on the grounds that I enjoyed it’s idea and style story-wise, it had a great reason, however I sense that it wasn’t as intriguing as it might have been.

Two valuable things here that the article touches on would be the interaction between personal tragedy and hubris and the role that abuse plays in character formation or rather malformation. Just something to think about.

Though good can emerge from evil, this is a reminder that it doesn’t always. Sometimes evil just begets more evil.

This is extremely well done and clearly depicts the character arc. It makes me want to revisit Deadman Wonderland! Thank you for the article!

I love your writing style

Awesome writing

Very deep piece of writing! Question: tragic villain or tragic hero?