Inception: Anticlimactic or Satisfyingly Open-Ended?

In 2010’s Inception, Christopher Nolan tells a mind-bending science fiction story about the difficulty in discerning a dream from reality. The movie’s ending was one of Nolan’s most impactful endings – which is saying something, considering this filmmaker’s reputation – leaving audiences thinking, “What? How dare he end it there!” Even for moviegoers who could keep up with Inception‘s somewhat confusing plot, the ending is intentionally vague and open-ended. For many viewers, this is a point in the movie’s favor because it keeps us thinking about the movie long after it’s over. However, some viewers may consider this ending anticlimactic, frustrating, or disappointing. An analysis of this ending, as so many viewers have done so many times, may determine how anticlimactic it really was and may even reveal an answer to this open-ended question.

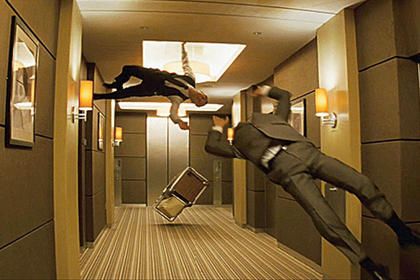

What Happened Here?

Leonardo DiCaprio stars as Dom Cobb, a master thief who uses science fiction technology to steal information from the target’s subconscious mind. When a powerful businessman offers to clear Cobb’s criminal record and allow him to return home to his children, Cobb agrees to attempt an unprecedented heist: planting an idea deep in someone’s mind (a process called inception), convincing the target to do something but tricking him into thinking it was his idea.

The movie’s ending revolves around one of the central tensions of the plot. Cobb’s technology allows him to share a dream with his team and the target, accessing the subject’s subconscious mind while they sleep. But there is a constant danger of the technology being used against Cobb, trapping him in a dream without him realizing it. To ward off this danger, Cobb uses “totems,” objects that follow certain rules in dreams as opposed to reality. One such totem is a top that never falls over once it starts spinning in the dream. If the top does topple, Cobb knows he is awake and can act freely.

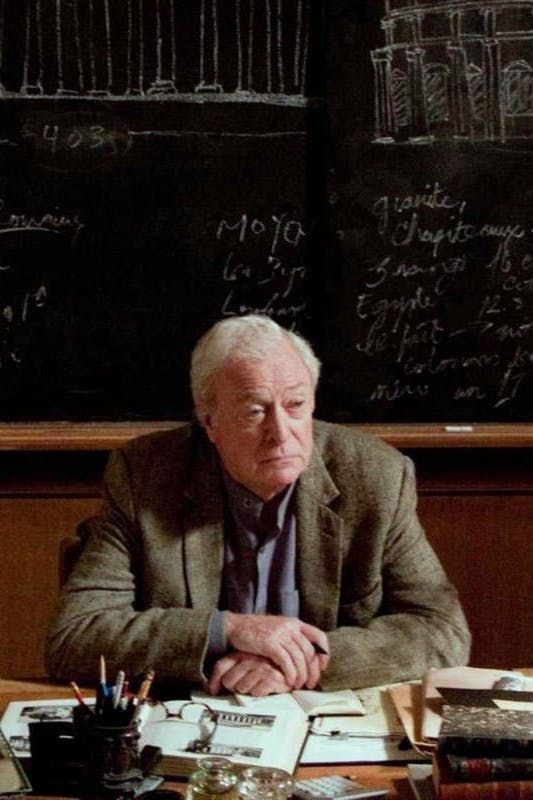

After the inception job is complete, Cobb returns home to find his father (Michael Caine) watching his children. As a final check, Cobb starts the top spinning on a table. He is distracted from seeing if it topples by his joyous reunion with his kids. The camera stays on the top, but before the audience can see if it falls or not… the screen goes black, and the credits roll. Viewers are left wondering: is Cobb still dreaming? Or did he get his happy ending after all?

This ambiguity may steal the happiness normally associated with a happy ending. Viewers might feel cheated, demanding a resolution, and form a negative opinion of the movie as a whole because of this. It is an understandable position. Any experience, no matter how positive, can be ruined by an unsatisfactory ending, as the ending is one of the things most likely to stick in a person’s memory.

Hook, Line, and Sinker

Most movies are made with the “lowest common denominator” in mind – appealing to the widest audience possible by trying to keep things simple – in an attempt to sell as many tickets and copies of the movie as possible. Christopher Nolan movies like Inception, however, tend to break that mold. As Vulture journalist Rob Stimpson explained, movies like this “aren’t supposed to be universally loved, nor completely understood, at least initially. But they have been discussed and dissected by viewers for hours, days, afterwards, and that in itself proves that a piece of art is having the desired effect.”

The intention of almost any piece of art is to evoke emotion. Anger and frustration at not getting a satisfying conclusion are emotional responses. If Nolan was expecting some people to be frustrated by Inception‘s ending, then he did a good job.

Another one of Nolan’s goals was, of course, to make money. The ambiguous ending prompted many viewers to buy another ticket to see the movie again in theaters, possibly many times. It later prompted audience members to buy copies of the movie on DVD or Internet streaming services, so they could continue to re-watch and analyze the ending.

Inception was the fourth highest-grossing film released in 2010, beating several movies designed to appeal to audiences based on the “lowest common denominator” formula: a Twilight movie, Iron Man 2, and animated classics like Tangled and How to Train Your Dragon. The ambiguous ending is no doubt one of the things that brought in so much box-office proceeds: over $836 million dollars, more than five times the film’s reported budget. Nolan clearly achieved his financial goal.

In defying the “lowest common denominator” trend, Nolan assumes his audience is intelligent enough to follow along with his vague sci-fi explanations of the movie’s plot. The ending, too, assumes a certain intelligence. “The audience is required to work,” Stimpson points out in his article, “and not every member of a cinema audience is happy to do so.” Viewers who criticize the ending for being anticlimactic may, in part, be expressing their frustration that a piece of entertainment is making them think. Viewers who like thinking, though, appreciate an opportunity like this.

Does It Even Matter?

As can be expected, Christopher Nolan has been frequently interrogated by audiences who would prefer a resolution to Inception‘s open ending. In a 2015 speech to the graduating class of Princeton, Nolan stated, “[Cobb] was off with his kids; he was in his own subjective reality. He didn’t really care anymore, and that makes a statement.”

The thing that keeps Cobb from seeing his children in reality is an event that Cobb feels responsible for: the death of his wife and the children’s mother. After the events of the movie, Cobb has conquered his guilt. That character development really happened, despite the fact it occurred while he was in a dream. Cobb is now willing to return home and see his children, regardless of whether he is legally allowed to or not.

The fact that Cobb does not wait to watch the top in the final scene suggests it doesn’t matter to him. And if it doesn’t matter to the movie’s protagonist, perhaps it shouldn’t matter to the audience. “Perhaps,” Nolan suggested, “all levels of reality are valid,” including dreams.

Arguably, the most important part of the film’s resolution is not Cobb overcoming the external obstacle of being legally forbidden to see his children again. The important part is Cobb overcoming the internal obstacle that was stopping him. That is the part audiences can most easily relate to: sometimes, the biggest thing holding people back from accomplishing their goals is their own unwillingness to do it.

Still Not Satisfied?

All that being said, if there is a chance of finding an answer to this ambiguous ending, film analysts will find it. As Stimpson wrote in his Vulture article, “for some, being a part of a movie, being able to contribute a part of yourself to a completed vision of a film is a liberating experience.” Another one of Nolan’s possible goals for the movie was empowering audiences to search for evidence and form theories.

One thing many viewers find on closer inspection is an important fact about the top: it was not originally meant to be Cobb’s totem. It was his wife’s, and he only started using it after she died. Based on this, there is no requirement that the top should defy physics in dreams. Cobb’s subconscious mind is not necessarily holding the top upright while it spins, so it could fall, even if he is dreaming.

However, it is entirely plausible that Cobb has adopted the top as one of his totems in his wife’s memory, convincing himself that the top will follow his wife’s rules in dreams. He is seen using the top multiple times during the movie, strongly implying that he expects it to act as a “reality test.” Unfortunately, understanding this does not prove one way or the other if the final scene is a dream.

However, this does lead audiences to another point: if the top is not Cobb’s totem, he must have a totem of his own. He instructs everyone on his team to get a totem to help them avoid getting hopelessly lost in dreams; presumably, he would have followed his own advice even before Mal’s death.

Many viewers have theorized that Cobb’s wedding ring is his totem. In scenes that are assumed to take place in reality, Cobb does not wear a wedding ring. In dreams, he wears it. Presumably, this is part of Cobb keeping his wife’s memory alive. When he is dreaming, he likes to pretend he is still married and not a widower, so his subconscious creates a wedding ring for him. Careful analysis of the final scene has revealed that Cobb is not wearing a ring, which suggests he is not dreaming.

This theory has multiple potential issues. For one, it is unlikely that Cobb would have made his wedding ring his totem when he first started using the dream technology. At that time, his wife was alive, so he would have worn his ring when he was awake. If he could make the wedding ring his totem after his wife’s death, there is no reason he could not do the same for the top.

More importantly, if Cobb’s wedding ring was his totem, there would be no reason for the top. All he would need to do to check reality is look at his hands: ring? Dream. No ring? Reality. Again, the number of times Cobb seems to be using the top as a reality test implies that he has adopted it as his totem.

Meanwhile, the wedding ring acts like a totem for the audience. The movie never directly states that Cobb only wears the ring when he is dreaming; that is inferred by watching the movie very carefully. It is possible Nolan left this clue for viewers to find to satisfy their desire for an answer.

Another point worth mentioning is the Occam’s Razor approach: most movies have happy endings, so why not assume the same of Inception? The genre and Nolan’s filmography do not give reason to assume this movie ends unhappily – it is not a horror movie made by Alfred Hitchcock, for example. Assuming, for now, an equal chance of the ending being real or imagined, an optimistic worldview increases the chance that it is real.

The Ultimate Reality Check

The most convincing piece of evidence comes from Sir Michael Caine, who plays Cobb’s father-in-law, Professor Stephen Miles. While speaking at a film festival in 2018, Caine confessed that he had been confused when he first read Inception‘s script. He asked Christopher Nolan about it, and Nolan kindly cleared something up for him: “[Nolan] said, ‘Well, when you’re in the scene, it’s reality.'”

At first glance, this looks like a director/writer helping an actor understand a scene and his character. Caine knew he would never be playing a projection of Cobb’s subconscious, so he would never need to do anything strange. For example, in the movie, mental projections sometimes act overly suspicious of the main characters as the subject’s mind starts to detect intruders. Projections from Cobb’s mind in particular frequently attempt to sabotage him during dream sequences. It was useful for Caine to know he was always playing a “real person.”

But this insight has implications reaching far beyond Caine’s acting. In a scene in the movie’s first act, Cobb meets with Miles about one of the members of his heist crew. During the conversation, Miles says, “Come back to reality, Dom.”

Sir Michael Caine has a reputation for playing wise mentor characters who ground Christopher Nolan movies in reality. In Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, for example, Caine plays Alfred Pennyworth, the butler who is always there to remind Batman of his “real life” as Bruce Wayne. Alfred pulls Bruce back to reality, just as Professor Miles invites Cobb to stop living in dreams and return to the way things were, as much as that’s possible. Caine’s characters are the ultimate reality check. Thus, Nolan saying, “when you’re in the scene, it’s reality” is very true and very important.

Professor Miles represents Cobb’s one remaining link to his old life. The only other reasonable link is his children, who he is forbidden from seeing. Considering he expects to be arrested as soon as he returns to America, it seems like an awfully big risk for Cobb to make contact with Miles. He does it because Miles is the reality check for when he’s awake.

And then Professor Miles appears in the final scene, confirming for the audience that (if Nolan is to be believed) the ending is reality. Of course, even if it was a dream, it was a happy ending for Cobb, and that is what really matters.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I like that his films always have a slick and stylish look to them. However, more than that I think he is a great story teller and this translates well in his films. Inception was a great story and it is one of the few occasions I’ve come out of the cinema with the wife discussing the film long after its initial viewing.

I’m not sure he’s a great ‘story teller’, he’s good at thinking of a story as a conceptual piece or as a thought experiment but story telling derives from good narrative & the problem with Nolan’s attempt at narrative comes from the heavy burden of exposition. The running gag among my friends is that Mr. Basel Eexposition writes for Nolan’s films.

Case in point. Imagine a scene with a group of character staring at a painting. You can’t see the painting itself but good story tellers can tell you what kind of painting they’re witnessing & how it makes them feel just by facial expressions, body language, lighting, music, the small natural subtleties that doesn’t require any dialogue. kieslowski, Kubric, Wenders could do that but not Nolan. He would have to have his characters talk & describe what they’re seeing, describe how they’re feeling & why. And that is just poor narrative story telling.

It is very subjective, isn’t it? His films ask some great questions, which are part of his story telling appeal; an example is the fact that he has asked the audience to think about its villains’ motivations, as opposed to just admiring their “muscle”. The same could be said with his heroes/ protagonists, most of which are indirect kind of characters that don’t really conform to the traditional anticipations of classic heroism; this for me is an example of his thought provoking style that few others can pull off. In my opinion, I don’t think Nolan short changes the spectators, he trusts in the audience interest and willingness to be entertained and this attitude allows for his trademark use of directorial metaphors in big budget Hollywood blockbusters and in spite of this he still maintains appeal across the board, rather than just the lowest common demographic of movie goers. Ultimately only a captivating storyteller could achieve that.

I definitely agree about Nolan’s tendency towards exposition. Love is the major theme of Interstellar, but instead of just letting the film do its work Anne Hathaway has to verbalize it to the audience.

Ambiguity can be a good way to close off a story (and often is), not just for setting up the potential of a massive cinematic universe franchise with spin-off movies for every extra or whatever.

Whilst this movie did have a certain uniqueness to it, and a challenging ending as well as flawless acting on the part of DiCaprio, I just feel that the ‘dream states’ became far too rigid towards the ending. It became very easy not only for the characters but also for the audience to follow the ‘dream within a dream within a dream’ segment, almost too easy. Each character seemingly had a clear grasp of which dream was which and how far they were away from reality. This contradicts Cobb’s initial notion that even for an experienced ‘dream extractor’ such as himself it can be very easy to become lost or confused about what is a dream and what is a reality. We were teased with some brilliant merging of dream and reality near the beginning of the film, when Ariadne in her first dream with Cobb became confused and had no recollection, along with the audience, on how she turned up sitting at a table along with Cobb. I was immensely satisfied with this as you could completely feel Ariadne’s confusion and cluelessness along with her, as neither her nor the audience had been given any clues by Cobb on how they ended up in a dream state until Cobb explained. Unfortunately, scenes such as this one were sparse throughout the remainder of the film, as the characters began to provide far too much context and explanation of how inception actually worked, leaving the audience nothing to think about or piece together.

The merging between ‘limbo’ and reality was beautifully intertwined however, with both platforms supposedly being so far away from each other (reality at the top, limbo at the very bottom) that they actually became merged. Both platforms were so far apart, it became difficult to tell what the actual differences between the too were, explaining Mal’s rationale that limbo was reality.

All in all, Inception was a film that provided food for thought, but did not delve into the infinite depths and subtlety that a dream possesses, leaving the audience feeling slightly underwhelmed.

Leaving YOU feeling slightly underwhelmed.

And others but not the audience, as you can’t possibly speak for everybody who attended the same screening of the film as yourself. Or indeed for every single person that watched the film.

My intepretation of the ending was that it was a tad too perfect for Cobb and close to his dream. The logical conclusion to draw was that he was still in fact dreaming but his mind was working to convince him that he was in the real world and had won.

Cobb though is too far gone by that stage to care one way or the other. BUT it’s just as likely that Cobb did succeed and was reunited with his kids in the real world.

Either way, I’d love to see a sequel.

I enjoyed the film a lot, but I did feel that the dream levels weren’t very “dreamlike”. They basically corresponded to different movie genres. For instance, the “snow level” was very much just a straight Bond-type espionage sequence.

Now, given all the different things going on, and the more confused/intertwined parts elsewhere, I can see why that’s a good choice for a mainstream film – and it does make it easier to make “staying alive” seem more important – but I still thought it was a shame.

All Nolan’s films are inclined to “say and show” – nothing can be left unexplained, no frame left silent, everyone talks about what they are doing and the entire history of why they are doing it. It’s a little irritating here (because you can feel that the character’s conversations are directed at you-the-audience rather than each other), but in Interstellar it ruined many great sequences, and mangled the emotional content.

Interesting comment. I was looking forward to Interstellar – though only for the fx, as I was aware of the (some might say excessive) sentimentality of it all. It does touch on some interesting themes – in particular, the strangeness of our children aging faster than us – but I find it an irritating movie, and it has Nolan’s fingerprints all over it. In no way, shape or form can he be considered the spiritual successor of Kubrick. Not now, not ever.

That said, I still have the final half hour to go, but I doubt my opinion will change. So far, I consider Interstellar to be merely Prometheus’ cousin. No more, no less.

He wants to be Kubrick, but he’s much closer to Hitchcock.

I thought Inception was an interesting, thought provoking and accessible essay on the nature of reality, existence and the human condition.

And, if you want to boil it right down to its core, its about a bloke trying to return to his kids.

The ending isn’t a dream. The spinning top was never his totem. It was his wife’s. His was his wedding ring which he does not wear in the ‘reality’ stages at the start of the film. However, he is wearing it throughout the main mission where he is dreaming, where his wife is still alive. Then at the end of the film where he is handing over his passport you can clearly see that he is no longer wearing it. This suggests that the ending of the film IS reality.

Okay, now I have to watch this again – I’ve already seen it twice but I think I can make that sacrifice. 🙂

I thought I was doing well with Inception; I followed and understood it for three quarters of the film. Then I literally lost my thread. I felt like Hansel and Gretel out in the woods. But I still think Nolan is a great filmmaker.

I personally do not like unknown, make it up as you see fit endings. I don’t know anybody who thought the ending was good. Great file rubbish ending. Loads of movie makes try to be a bit different with the endings, but in the end, we as viewers, like to see a proper ending. From the beginning of time stories have been told, and they have a final non misunderstood finish…except now people are left unsatisfied in the name of art rather than entertainment.

You don’t know anyone who thought the ending was good? That says more about who you hang around with than it does about the film to be honest.

Speak for yourself, some people’s minds like to wonder, speculate, build, interpret and discuss.

– I don’t know anybody who thought the ending was good.

Well, you do now. It doesn’t matter if it’s still a dream or not cos Cobb no longer cares. Although the ending is too good to be true…

Other great films with ambiguous/enigmatic endings (which help make them great):

Citizen Kane

2001

The Shining

The French Connection

Apocalypse Now

Blade Runner

The Thing

Total Recall (Yes, Total Recall – the Arnie one!)

Barton Fink

The Usual Suspects

Drive

Interstellar – does Cooper keep going and maybe end up in the far future? Perhaps he is ultimately responsible for the tesseract/sending the messages through time in the first place…

I liked the ending, it was ambiguous, forces you to come to your own conclusions. Memento had something similar, nothing wrong with that at all.

It’s a classic device for ending a film with a question and a little ambiguity. A bit like the old “The End” followed by a question mark.

Cobb’s real totem was his wedding ring.

So basically he’s wearing it when dreaming bit not when awake, is that how it goes?

Always suspected the Big Heist is elaborate therapy concocted by his friends to help him return home.

Such a good film, even the snow sections. Never really thought the ending needed an overt explanation, just like The Sopranos climax didn’t need one either.

Very overwrought and ultimately unsatisfying film. The snow scenes are redolent of a dated Bond film. The spinning top at the end was there to distract viewers from the fundamental emptiness of the film, so they leave scratching their bonces saying ‘intriguing ending’.

Obviously you were in a dream level when you saw this as it was quite different from my reality: engrossing, enjoyable and sufficiently interesting to provoke subsequent discussion. Nolan improves with each outing.

Although I neither loved the film or hated it, I just thought it was fine, a nice, entertaining way to spend a few hours. If it really was a clever film it wouldn’t need Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s character explaining what is going on every five minutes, A film should be understandable by it’s actions and content, not hammy exposition by a token character.

A phenomenal film on so many levels.

Mind blowingly brilliant.

Very interesting analysis. Everyone usually sticks to their guns on their preferred interpretation so this made for a very interesting exploration. Well done.

In a sense, even if the end was merely a dream, it was the best ending in that it was happy. Good job.

It was Schrödinger’s totem. We don’t know exactly what happened next.

The film-maker explained that he saw the concept of reality in the film – and real life – as entirely subjective. So DiCaprio’s character doesn’t wait to see if the spinning top drops because he no longer cares to distinguish between a possible harsh reality and a potentially wonderful dream.

Similarly DeCaprio in Shutter Island chose a lobotomy over his reality.

I agree with this. We are focusing so much on the actual state of what is going on at the end (namely, whether Cobb is in a reality state or a dream state) but the fact of the matter is that he walked away from the top before it could fall.

Why? Some might say that it’s because he was certain of the state. But I think the more plausible (and indeed, interesting) answer is that, as you pointed out, he no longer cared.

This poses an important question about our lives, which is very similar to what The Matrix tried to do: if you could pick between a terrible reality and a wonderful dream, would you always pick the former? Because psychologically it seems that many would choose the latter. Why, again?

Well, think about this: why does it matter, as long as it feels real?

Inception was a dream inside Shutter Island was a dream inside Inception.

Was a dream inside Basketball Diaries.

I prefer the Simpsons Inception.

Great film and what a soundtrack! I like listening to it when navigating public transport drunk – gives the journey a surreal edge…

Completely agree. I love his visual style and his collaborations with Hans Zimmer always lead to an incredible audial experience, especially with Interstellar.

Completely agree with both of you! Love the soundtrack, film..and Hans Zimmer is amongst my favourite composers. Can I recommend Harry Escott’s ‘unravelling’ from the movie Shame? Great to listen to whilst traveling (particularly on the train) and similarly haunting!

Well IMO Christopher Nolan’s movies make the world a more interesting place; it would be boring if every movie was like Iron Man or Transformers… but Jesus H: Inception felt – at times – like I was back at school learning algebra!

This film reminds me a lot about the anime Paprika.

Paprika was alright. I honestly preferred Tokyo Godfathers a lot more, though. By the same creator.

Can barely remember anything about this film, other than I definitely went to the cinema to watch it and it seemed to last for days.

I accept what you say but suggest that’s perhaps the point. Inception was one of those rare films that was utterly dazzling and engaging while watching it but strangely elusive when subsequently attempting to recall any detail of the narrative. Arguably, it represents cinema as an immersive experience, one in which the viewer can only truly derive any enjoyment while in the moment. Equally, I’m now inspired to watch it again in the hope that some of the more obscure elements become clear.

One of the most interesting films I’ve ever seen.

Now that I’ve read this, I am much more interested in the film.

‘Inception’ is Kubrick level cinema genius.

It was a perfect ending to a very good film.

If only he’d made the ending to TDKR in a similar fashion.

In the end reality is what you choose for it, and the material is just as open to interpretation to the audience as it is to its creators. I believe that the ending a person believes says more about them than anything else.

Postmodernist film like Inception hinges on ambiguities. Whether or not Cobb manages to return to reality does not matter – in the filmic world, reality and dreams often mingles with each other. The existing ending is the best ending the movie can ever have.

Interesting! I agree that the point isn’t whether or not he actually made it back; it’s what could have happened and it no longer matters to Cobb himself whether or not he’s ‘living in reality’ because he chooses to believe ‘this reality’ that he sees.

I reckon the reason they left it ambiguous was to set up a possible sequel if anybody wanted to fund it.

It’s a lot harder to sell a sequel to a movie with a satisfying conclusion.

I wonder to what extent, if any, Nolan telling Caine that his scenes were reality was simply to ensure he grounded his character and didn’t concern himself with questions of whether his scenes were real. Regardless, your point that Caine’s character represents Cobb’s remaining link to his old life seems like a valid interpretation of his role. In any case, articles like these must be exactly what Nolan’s aiming for with such ambiguity.

While the ending does warrant thought, I think we may have slightly overbloated its need for discussion. The genius in the ending, I think, lies in its simplicity, something that we so often take for granted.

Nolan strikes me as a rare artist, one who recognises commercial practicality without compromising artistic integrity. He wants us to have a good time at the theatre, but he also leaves us with just enough to ponder when we leave.

As a lucid dreamer, I absolutely adored Inception and found it’s open-ending to add to its appeal, but I know not all people think the same. Nevertheless, I appreciate you delving deep into this controversial ending. Well done!

Thank you for writing this piece! I love this film, and I think that it’s ultimately a satisfying cliff hanger. It gets everyone talking and discussing. You can’t ask for much more than that.

I personally love the ambiguity and open-ended nature of Inception. It leaves it up to us to interpret the ending with what information we’ve been given, and how our own reality interlaces within the film’s plot – the way I think cinema should be received. Nolan seems to find an immaculate balance between telling a story, and leaving it up viewer imagination – you leave this movie wondering for DiCaprio – did he get his reality, or does he remain stuck? This wonder wandering its way into our own reality after the ending of the fictional world on screen is a challenge Nolan perfects within Inception.

This movie was neither for me.