Absences in Theo Angelopoulos’ Landscape in the Mist

The dreamy, magic-like final installment of Theo Angelopoulos’ Trilogy of Silence, Landscape in the Mist (1988), focuses on the quest of a young brother and sister to search for their absent father. On the young siblings’ adventure, they encounter events that mature them along their way. And not only their father, various absences were employed. These absences ultimately are used to convey the loss of Greece’s traditions. The discussion below will explore how absences are used as an effective tool to reflect how the children’s courageous quest is doomed from the start.

Absent Parents

The film opens with a five-year-old Alexander (Michalis Zeke) and an eleven-year-old Voula (Tania Palaiologou) trying muster up their courage to board a train to Germany. It is then cut to the opening scene in dark, in which the children are in bed, trying to sleep. Alexander asks Voula to tell him the Genesis tale again:

In the beginning, there was darkness. And then, there was light. And the light was separated from the darkness, and the earth from the sea, and the rivers, the lakes, and the mountains were made. And then, the flowers and the trees, the animals, the birds.

In the darkness, we hear the siblings’ mother’s footsteps, to which the slightly annoyed Alexander says quietly afterward, “The fairy tale will never end. She kept interrupting us.” It is as if Alexander foretells his own fate in the movie. While a mother is supposed to be a loving caretaker and protector, in the movie the audience never sees her on the screen, or even hears her voice. All she had in the entire movie is this scene in which she checks on the children—a complete absence of affection and even connection from the mother to the children. On the other hand, Voula mentions about worrying their unannounced trip might have upset their mother in her letter to her “father.” But the reverse does not seem to be true.

Later, when the children get discovered and thrown off the train for not having train tickets, Voula lies about where they are heading. She tells a police officer they are visiting an uncle, the brother of her mother. As a result, the children are taken to the uncle, who shows welcoming gestures at first. But as soon as he sits down with the police officer, he tells the officer that he will not be taking responsibility for the children: he does not share a close relationship with their mother. What is even more important was, there is no father in Germany. It is only a lie made up by the children’s mother. The uncle even implies that the children are the result of their mother’s one-night-stands, and it is very likely that they have two different fathers due to her promiscuity. In this light, the children’s mother is far from an ideal mother: not only does she never want to have the children in the first place, she also never looks for them when they go missing. Her cover-up about the children’s father’s truth lead to them going on this trip of no return.

As a result, the young siblings’ father and mother are already absent early in the movie: mother from the screen, and father in the children’s life. In a filmic world where parents are absent, it is as if the children are under no absolutely guidance.

Angelopoulos himself went through a similar event in his personal history: his father was arrested and deported from Greece without reasons after Greece’s liberation from Germany. Although his father eventually came home after nine months, this episode made an impact on him. Such search-for-father theme appeared in the director’s 1984 work Voyage to Cythera as well, and in the film, the imagination of meeting his father Spyros in Voyage to Cythera by Alexander the film director, and the search for a non-existent father in Landscape in the Mist were, ultimately, Angelopoulos’ tributes to the Greek epic poem, Odyssey, which is a story of the Greek king Odysseus’ journey home after a decade-long Trojan War, and his son Telemachus’ search for his missing father in the meantime. But unlike Odyssey, the father in the movie never comes home, and the children never get to see their father.

Later in Landscape in the Mist, the children would get to meet Orestis (Stratos Tzortzoglou), who is a traveling player of a theater troupe. In the theater troupe Orestis belongs to, the patriarch, who has the biggest power and say over matters of the group, is “Grandfather.” Orestis and the children part way in the middle of film, but when they meet up again later, Orestis finds out that his troupe plan to sell all theater costumes because they can no longer perform. To which Orestis protests and asks to meet with Grandfather, in hopes of Grandfather coming out and putting a stop to the decision. “He is sick. He doesn’t want to come out.” says one of the theater players. Interestingly, the important father figure in Orestis’ troupe is, again, absent from our view in the film entirely.

Both Alexander and Voula’s parents, and Orestis’ Grandfather, are not present in their lives. It is almost saying in the melancholic world of Landscape in the Mist, all children are, again, on their own, without any sort of guidance.

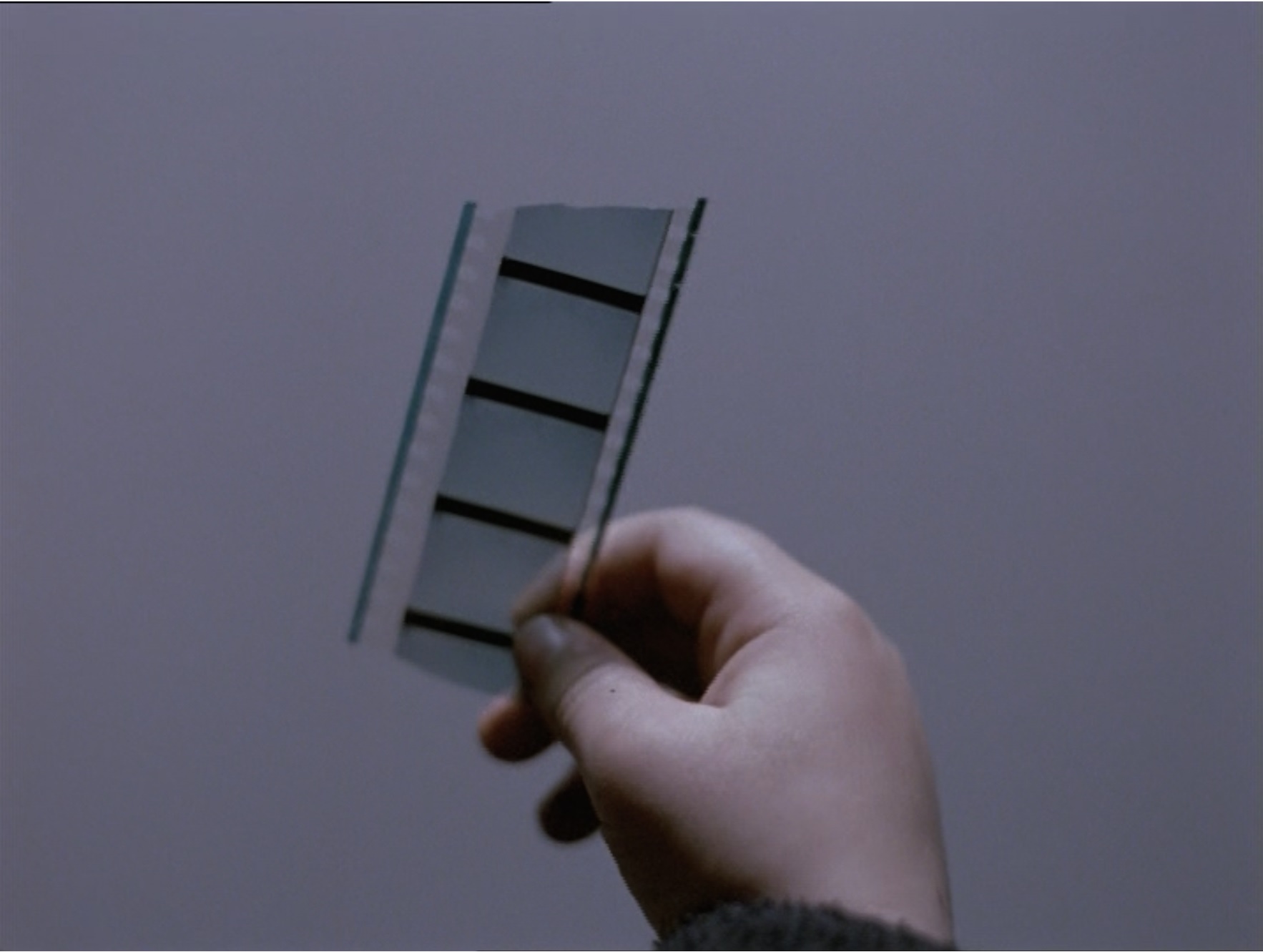

Invisible Tree

And in the middle of the night, when Orestis and the children are wandering in the dark, Orestis finds a small piece of a roll film. He kept saying he could see a tree on the film, but the children both replied that they cannot. “Beyond the mist, back, in the distance. Can’t you see a tree?” “No.” replied Alexander. “Me neither. I was kidding.” The tree signifies the tree of life, or a person’s lifeline, from the Bible’s Genesis. It is also where the light and darkness tale comes from. The absence of tree, again, would predict the children’s final destination and the film’s ending, as well as the fact that the Genesis tale never quite comes true.

Missing Finger

Shot from the children’s point of view, the film is consisted of various strange things: a bunch of people staring at the snowy sky unmoved, a violin player goes into a restaurant, where the five-year-old Alexander is working to make money to feed himself, and starts playing the violin. Angelopoulos expert Andrew Horton pointed out that the “magical” scenes from Angelopoulos’ films came from Byzantine Orthodox traditions, which often made Angelopoulos’ film almost as magical as surrealist. One of these strange scenes include the giant marble hand extracted from the sea:

Marble sculptures are reminiscent of Greek sculptures. The marble hand represented Greek history due to long formation of the stone, the association with sculpture, and the strange, dream-like element of the Byzantine tradition. But the more interesting point is, of course, the missing index finger. The index finger is usually a pointing finger, which represents authority and command. In this scene, the marble hand rose from the sea to the sky is missing the finger. It can only be interpreted as a loss of authority and guidance power, hence the loss of Greece’s importance in history in comparison to the status of Greece at Angelopoulos’ time, or even today.

Just as the glory of Greece’s past, the children do not seem to have a happy ending. At the end of the film, when the children arrive at the “German border” by a boat—audience should know that Germany cannot be reached by solely traveling through Greece—we hear a gunshot in the dark. Although the children wake up in daylight eventually, it is implied that the ending is merely what the children see in dreams/heaven. Only in heaven can Alexander and Voula found the tree of life, in the distance, shrouded in mist, and God the father.

In summary, the absences of the film represented the reverse of all the Greek traditions: the father never comes home, the children never get to even meet their father once, the tree of life from Genesis can only be found in imagination/Heaven, and the giant marble hand is now missing the authoritative index finger. A coming-of-age story turns out to be a story of misfortune. All that is left for the children is doom.

Works Cited

Horton, Andrew. The Films of Theo Angelopoulos: A Cinema of Contemplation. Princeton, Princeton UP, 1997.

Koutsourakis, Angelos, and Mark Steven, editors. The Cinema of Theo Angelopoulos. Edinburgh, Edinburgh UP, 2015.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Every once in a while a great film comes along which seems to transcend the medium. I think this is one of them.

Being a mom of 2 now after the years of watching the film, I miss the kids in the movie. It’s weird.

Aristotle would have loved this film.

Very cruel, when a story is inspired by a sacred two children’s dream, the worst you expect is that it will turn into a horrible nightmare. The rape of an 11 year old girl in the back of a truck is so tedious and disgusting that destroyed the visual beauty of the film.

I feel this movie is just a compilation of random images with no resemblance of narrative pacing or rhythm whatsoever. I’m not saying this because I don’t like this sort of movie. It’s quite the opposite, I love Tarkovsky. That’s film poetry. This is nothing.

I have to agree. It’s visually pleasing, but lacks consistency to create some sort of meaning, some metaphoric images are interesting, but then they’re just completely out of touch with the rest of the film.

The most gripping part of the entire film was when a helicopter came and lifted it out of the water… it was captivating and seemed to possess far more meaning than it possibly should have.

An exemplary movie which needs more recognition!

I have the Artificial Eye Boxed sets, and all the films seem to be missing up to 5-15 minutes, are there no definitive versions of Angelopoulos’ films?

I do see this depth from the Ancient Greek and Biblical traditions. Nice article!

I live how the rain pours almost constantly.

Theo Angelopoulos mastered the art of visible but not too in-your-face symbolism while leaving the space for mundane scenes. Thanks for covering it.

What a gorgeous and poetic film. Almost as beautiful as the same director’s “The Weeping Meadow” – one of my all time most admired works of art in cinema.

Very good analysis. To me, each scene and episode in their young lives on this journey through Greece to find the landscape in the mist, can be linked to the story of the Greek nation and its people.

This is the kind of film that may grow on revisiting, and I certainly plan to see it again after reading your take on it.

Seen the movie in HK International Film Festival over 20 years ago and still could not stop crying whenever I think of the kids in the movie.

The ending is quite transcendent and unforgettable.

I saw this movie when it was playing in Berkeley in 1990. This is one of the most beautiful and haunting films I have ever seen.

A great broad social criticism on contemporary Greece of the 1980’s.

Nice analysis. Going to watch the film.

The consistent gloomy weather throughout the film makes one wonder whether the director suffers from severe depression. 🙂

I seem to have the same reaction to each of Angelopoulos’ films; flawed genius. But in each film, the flaws and what feels masterful is different.

I watched this recently. I admit the stuff going on was not as interesting as seeing the picturesque landscapes and scenery of the scenes.

A movie that still lingers in my brain from time to time.

Saw this film in a local movie theatre around 30 years ago. I am an ignorant. I didn’t understand much of it.

It so powerful and yet so sad.

I love the way this maestro director has used a sort of Odyssey (what could be more appropriate?) by two young siblings.

It was visually stunning.

This is one of those films where, even without thinking, the perfection of its image and message succeeds in moving the viewer.

This film was featured in the book of 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die!

Loved the ending of “The Travelling Players” as well.

A wonderful article and thanks for introducing me to a film that I need to watch.