Literature’s WWI Veterans

Not many people experience military life. Even fewer experience combat. When we read about fictional veterans we all expect something different: perhaps a tough guy, a gentleman, a jerk. Most likely though, we expect to see evidence of war in his character: a breakdown, a moment of violence, the unexplained disintegration of a relationship.

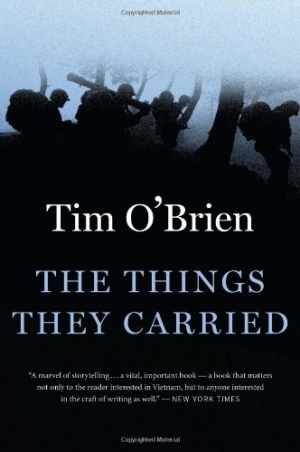

Veterans who have fought recently in Iraq or Afghanistan have been written about in publications like American Sniper, Lone Survivor, Redeployment, and Sebastian Junger’s War. Most of these authors have either experienced combat or spent countless hours with someone who has. Tim O’Brien, a Vietnam veteran, has a seemingly endless list of novels on the Vietnam war, including The Things They Carried and Going after Cacciato. Both novels were on top selling lists and are taught in high schools. Then there are the classic war novels like Tolstoy’s War and Peace, or Homer’s Iliad. There is a never ending list of novels about war and veterans from all time periods and places. War doesn’t end. Neither does the need to read and write about it.

Veterans who have fought recently in Iraq or Afghanistan have been written about in publications like American Sniper, Lone Survivor, Redeployment, and Sebastian Junger’s War. Most of these authors have either experienced combat or spent countless hours with someone who has. Tim O’Brien, a Vietnam veteran, has a seemingly endless list of novels on the Vietnam war, including The Things They Carried and Going after Cacciato. Both novels were on top selling lists and are taught in high schools. Then there are the classic war novels like Tolstoy’s War and Peace, or Homer’s Iliad. There is a never ending list of novels about war and veterans from all time periods and places. War doesn’t end. Neither does the need to read and write about it.

If we look at the canon of war stories, fictional veterans changed after World War I. During this time, the term “shell-shocked” was first used to describe soldiers who suffered from severe mental and emotional distress as a result of combat. Still, soldiers who had what we now called Post Traumatic Stress Disorder were considered weak, feminine, or faking it. George L. Mosse, author and historian, notes that WWI doctors believed that “the shell-shocked soldier must be treated like a stubborn child. Even the grudging admission that there were some who could not go back to war did not keep psychiatrists from treating most of the shell-shocked as if they were shirkers.” 1 Fictional war heroes after WWI were no longer traditional heroes, but broken men. Society couldn’t quite understand them.

It is difficult to draw a line between a stereotype and a well written character, since many veterans do fall into our preconceived idea of how one deals with an extreme and violent past. Take Modris Eksteins’ point in The Rites of Spring, for example. He tells a story of a man during WWI who visited a medical station as wounded soldiers were being brought in, in the hopes of getting an interesting story. However, “he was stunned to hear survivors spouting the same clichés contained in newspaper reports of the battle. ‘None of them could provide the slightest original reaction.'” 2 As a military man, trained to obey orders, and thrown into situations of death repeatedly, countless WWI veterans lost their humanity.

For these reasons, it takes a talented writer to create a WWI veteran who is so human.

Septimus in Mrs. Dalloway

“Hysteria” in the Fighter

Since it would be difficult to discuss every World War I veteran in the canon of literature, this article only looks at three distinctive WWI veterans who appear in novels that aren’t about war. Without a war to fight, these soldiers give an outside perspective on civilian life.

Virginia Woolf didn’t know much about combat, but she knew about mental illness. She also knew about the resulting struggle of fitting into society. Septimus Warren Smith’s story parallels the story of Clarissa Dalloway, the female protagonist, in their struggle to find their place in uptight, early twentieth century England. They reflect each other. Septimus has lost his grip on reality, while Clarissa grips it all too tightly. In many ways, Septimus is Clarissa turned inside out, without the dresses, flowers, and parties to keep her all together. In this way, Septimus isn’t a veteran used merely as a dramatic or sympathetic plot device. He is the problems of the characters and of society laid bare.

Such problems are evident because of Septimus’ femininity. He is effeminate in the traditional sense. He is sensitive and emotional; he loves literature and beautiful images. At the same time, he was a soldier. His soul is metaphorically androgynous and therefore society can’t accept him.

His doctors, who Septimus doesn’t like or trust, keep prescribing rest. Sir William Bradshaw suggests time away in a relaxed state, but this only frightens and angers Septimus. Rest as a cure was often prescribed to “hysterical” women (hysteria coming from a Greek word meaning “womb”). Mosse, when talking about the early twentieth century, says that “there was a consensus in western and central Europe about what it meant to be a ‘true man’ … Such a true man was a man of action who controlled his passions, and who in his harmonious and well-proportioned bodily structure expressed his commitment to moderation and self-control.” 3 A shell-shocked veteran then, defies all these definitions of a “man” as sturdy, unchanging, not hysterical, tough, and in control.

Woolf, writing Mrs. Dalloway in the early twenties, had little knowledge about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in WWI veterans due to the lack of psychological information available. Therefore, we must look at Septimus, not as a true portrayal of a veteran necessarily, but as a portrayal of how society fails those in need. By writing a sympathetic war veteran with an illness associated with women, Woolf critiques society’s treatment of not only veterans, but of all ostracized citizens.

Of all of Woolf’s beautifully elongated sentences in Mrs. Dalloway, the ones belonging to Septimus are the most poetic. Take for example, when Septimus watches a plane:

“It was plain enough, this beauty, this exquisite beauty, and tears filled his eyes as he looked at the smoke words languishing and melting in the sky and bestowing upon him…unimaginable beauty and signaling their intention to provide him, for nothing, for ever, for looking merely, with beauty, more beauty! Tears ran down his cheeks.” 4

Woolf often equates beauty and pain in her novels. It is not surprising that her WWI veteran is both beautiful and isolated. Woolf captures the seemingly paradoxical combination of genders in a man expected by society to display the idealized image of masculinity. He is still beautiful, and society kills such beauty.

Shadrack in Sula

Adrenaline, Violence and Alcohol

Shadrack is similar to Septimus in many ways. For one they are war heroes without a war. They show the struggle of coming back home. They are, as others in the novels see them, crazy. His character, like Septimus, parallels the story line of the female protagonist, Sula. After coming home from the war, he also suffers from hallucinations. Still, Shadrack is described as drunk, funny, obscene, outrageous and loud. Unlike the seemingly timid and easily excitable Septimus, Shadrack is arrested by police for his drunkenness and his doctors do not treat him with kind words, but with restraints and physical threats.

Society thinks only of the horror of war, but many soldiers experience an undeniable adrenaline rush while in combat. Sebastian Junger in his novel War writes that, “War is a lot of things and it’s useless to pretend that exciting isn’t one of them.” 5 Shadrack encompasses this paradox of war more so than Septimus. Septimus represents the horror of war, while Shadrack represents both the horror and the powerful energy of it.

Morrison, a very different writer than Woolf, is much more gruesome with Shadrack’s war memories:

“Wincing at the pain in his foot, he turned his head a little to the right and saw the face of a soldier near him fly off. Before he could register the shock, the rest of the soldier’s head disappeared under the inverted soup bowl of his helmet. But stubbornly, taking no direction from the brain, the body of the headless soldier ran on, with energy and grace, ignoring all together the drip and slide of brain tissue down its back.” 6

A similar scene described by Woolf goes like this: “The last shells missed him. He watched them explode with indifference.” Woolf’s audience, most of whom knew a WWI veteran, would not have expected anything more graphic. A modern audience, however, is more comfortable with such brutality. While Morrison’s depiction may be tough to read, it is accurate. In Eksteins’ Rites of Spring he mentions a soldier’s experience that is strikingly similar,

“Suddenly our master marksman collapsed, shot through the head. Although his brains were running down his face to his chin, he was still fully conscious as we carried him to an adjoining tunnel.”

While she addresses the blood and violence, Morrison also addresses the alcoholic veteran trope quite successfully. When written well, it is not a stereotype but a truth for many World War I veterans. Morrison writes about Shadrack that “the drunk times were becoming deeper but more seldom. It was as though he no longer needed to remember that he had ever forgotten anything.” In The Pity of War, Ferguson discusses the importance of liquor for soldiers who were said to sometimes fall asleep in the trenches while waiting for the enemy because of the alcohol: “This was only an understatement in the sense that it did not mention the huge quantities of drink men consumed when they were not in the front line. Ordinary soldiers would get drunk at every opportunity; they had, as one officer in the Highland Light Infantry put it, a ‘marvelous talent’ for it.”” 7 Ferguson also describes the drinking habits of the men after the war, which weren’t much different. Morrison mentions, in only a handful of sentences, Shadrack’s alcoholism. While he has the characteristics of a WWI veteran, the constant drinking is not used as a tool to deepen or complicate his character. His humor and his curious actions often stem from drinking, and therefore the alcoholism is only an accurate depiction of many men suffering after the war.

Writing in the 21st century, Morrison can better understand the psychological effects of war and can also write to an audience more willing to understand it. Shadrack may be less poetic than Septimus in language, and in some ways more traditionally masculine, but he is still quite a beautiful and complicated character. While they differ, both Shadrack and Septimus are isolated from society, and while surrounded by people, suffer a great loneliness.

Jake Barnes in The Sun Also Rises

A Generation Lost

Earnest Hemingway was the only one of the three authors to experience war and combat. He was an ambulance driver and fought on the Italian front and was eventually wounded in both legs by mortar fire (much like his other WWI veteran character, Fredric Henry from A Farewell to Arms). His character Jake Barnes, unlike Septimus and Shadrack, is not isolated from people, is not treated by doctors for mental instability, and is not dysfunctional in everyday situations. Rather he is the most stable of his friends, particularly the drunken Scottish war veteran, Mike Campbell and the overly jealous Robert Cohn. As the observer, Barnes has great insight into the others of his company. He also has a war wound which makes him impotent. He is one of the only characters not to have a sexual relationship with Brett Ashley, though they love each other. These characteristics isolate Jake Barnes emotionally from others. At the same time, Hemingway is championed for his portrayal of the “Lost Generation,” and all of his characters experience isolation.

Unlike the aesthetically intricate language Woolf used to describe Septimus, Hemingway’s language is blatantly simplistic. As Adrian Bond writes, “Rejecting adjective, adverb and verb, Hemingway finds the only part of speech he can trust: the concrete noun…By placing weight on sensory experience, Hemingway instead privileges body over mind, favouring largely unconscious modes of knowing over those we traditionally regard as cognitive, the play of conceptualization and rationality.” 8 While Woolf values the conscious mind and life in the intangible, Hemingway was a man of concreteness with a distrust of the abstract. Jake Barnes’ character is one of action and experience outside of himself which, in turn, reflects the inner being. Septimus’ character is simply internal.

Hemingway’s shortened sentences and simplified diction allows us to see the body and the unconscious wounds of the character. While Woolf tells us exactly what is bothering Septimus through his conscious thoughts, Hemingway leaves such things to interpretation. But paradoxically, there’s not much to interpret. War happens, humans are hurt. Words are not to be trusted, only the body and it’s actions.

As Jeffrey Hart wrote in his evaluation of The Sun Also Rises, “the novel has made practically everyone who has written about it look foolish.” 9 The Sun Also Rises doesn’t capture war just in the characters but in the novel as a piece of art. War, like the novel, is hard to talk about and hard to make a truthful interpretation. Like war, the novel isn’t passive. Hemingway makes it clear that we can discuss such things intellectually. However, truth will never be reached. As Hart wrote in the same article, “[The novel] says, moreover, that you, reader, can share its special vision of beauty only when you have submitted to its special malice and allowed your ordinary habits of feeling to be violated.” War defines Septimus and Shadrack, but in Hemingway’s work, characters define war.

War lives within Septimus, Shadrack, and Barnes. But a soldier isn’t their only part to play. War is not what they represent. It is what they experienced. They are well-written characters because they are not idolized, nor are they pitied. Instead they reveal truth in life around them. They reveal beauty in people they meet for a moment. While society struggles to understand veterans, veterans clarify what it means to be human. As readers, such characters should help us understand a person who is is so rarely understood.

Works Cited

- Mosse, G. L. “Shell-shock As A Social Disease.” Journal of Contemporary History Vol. 35.No. 1 (2000): 101-08. Sage Publications, Ltd. Web. 17 Oct. 2014. ↩

- Eksteins, Modris. Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age. New York, Mariner, 1989. Print. ↩

- Mosse, G. L. “Shell-shock As A Social Disease.” Journal of Contemporary History Vol. 35.No. 1 (2000): 101-08. Sage Publications, Ltd. Web. 17 Oct. 2014. ↩

- Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. San Diego: Harcourt, 1981. Print. ↩

- Junger, Sebastian. War. New York: Twelve, 2010. Print. ↩

- Morrison, Toni. Sula. New York: Vintage International, 2004. ↩

- Ferguson, Niall. The Pity of War. New York, NY: Basic, 1999. ↩

- Bond, Adrian. “The Way It Wasn’t in Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises”” The Journal of Narrative Technique 28.1 (1998): 56-74. Print. ↩

- Hart, Jeffrey. “The Sun Also Rises: A Revaluation.” The Sewanee Review 86.4 (1978): 557-62. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The Sun Also Rises seems to be more a chronicle or a diary than a novel

Septimus’ thoughts were amazingly written, and that brings me to the second thing: Woolf’s way of writing is dazzling, warm and delightful. She makes me want to bathe in her words.

Literary masterpieces right here.

It had been 20+ years and I’d forgotten how morose Hemingway can get…but also how funny some of the banter is.

Very morose, indeed.

Sula is a remarkable novel written to express a relationship between best friends.

I hate all Hemingway. I seem to remember it was about some expatriates wasting their time in Spain doing nothing except getting drunk, going to bullfights, etc. I neither hated nor liked the characters; I just didn’t care.

I have nothing against Hemingway. I have been interested by Hemingway’s representation of masculinity that takes place in his work.

It’s funny, every time I re-read Mrs. Dalloway I feel as though I’m reading a brand new book. I always seem to forget about Septimus and about much more than Clarissa buying flowers.

These characters are very convincing and easy to love, especially Septimus.

A very well written article. All of these works provide a different outlook on the horrible effects WWI brought about on societies across the world. Hemingway’s involvement in the war as an ambulance driver for the Italian army puts another intricate spin on his works. Another interesting work on the period is Parade’s End by Ford Maddox Ford. I’d also be interested in hearing your take on some of the films and mini-series depicting the time. A recent series called The Crimson Field aired a single season on the BBC. It follows the lives of doctors and nurses at a British field hospital in France as they care for wounded soldiers.

What a strange, haunting book The Sun Also Rises is!

Sula is a book that made me feel a certain way. I really did admire this book.

The most interesting character in the books are Septimus.

It may be that The Sun Also Rises requires more than one reading to truly appreciate it, but in terms of my reading experience–I simply didn’t enjoy reading this novel.

I have to admit that at first I wasn’t too impressed with Sula in the slightest. Of course, Toni Morrison is a great author and I found the writing itself had a tendency to really pop out at you but the story just wasn’t holding up to my expectations.

Sula is such a strange, melancholy work. I found it rather confronting.

I find it hard to connect with characters like Septimus Warren Smith or Clarissa Dalloway; that might be a criticism of some books, but is not of this one. I get the feeling that Mrs. Dalloway was deeply personal to Virginia Woolf, a work that may not have ever been intended for the wide acclaim that it receives.

Very interesting ideas about authors who have not experienced war, though they experienced soldiers returning from conflict, and authors who did fight themselves. The idea of the “Lost Generation” or the “Greatest Generation” has pervaded literature since the events they describe. Today has seen a resurgence in appreciation for the services of soldiers and an even more interesting occurrence: Writing of stories containing soldiers from authors who don’t know veterans personally, but simply read of them in the news. In the age of communication how warped is the idea of a soldier’s experiences versus before when the world itself became veteran to war? Very good article, and worth further exploration, though as you say with so many books it would be quite the undertaking to examine the issue fully.

Septimus was one of the first characters to show the horrors of war and the trauma that occurs after combat.

Sula started slow but I liked the ending, especially when Sula returned..

I really enjoyed this article. The first two authors you mention have a difficult task– how do you write about war in a way that feels true to readers who may not have experience war as well? Interestingly, I think we trust writers more who have experienced combat (like Hemingway) because we want them to tell the truth, to give us a chance to experience war vicariously.

If I had read “The Sun Also Rises” when I was younger–or even a year or two ago–I would have been frustrated with it. Now, though, I appreciate it for what it is, and I can appreciate and understand the Hemingway style. Jake Barnes is such an interesting and tragic character.

Interesting breakdown of the portrayals of WWI veterans. I found it interesting how you were able to apply the thought of hysteria (once thought to be the aftermath of an unhealthy uterus) to Septimus’ character and his gender expression. Very intriguing.