The Modern Orphan Figure

More than perhaps any other genres, children’s and adolescent literature have inspired a lifelong love of books in generations of readers. Adults often return to their childhood favorites for escape and comfort, or to introduce them to new generations. However, not all children’s and adolescent literature is created equal. To stand the test of time, a book in these genres must be well-written. A key factor in how well these books are written is their protagonists. A truly great book for young readers will have a strong and somewhat independent protagonist, even if he or she is introverted, shy, or cautious by nature.

Authors make their young protagonists strong in several ways. Perhaps the oldest and most well-known way is making the protagonist an orphan. A parentless protagonist immediately faces huge external and internal stakes. Externally, there are no immediate nurturers to provide basic needs such as food, clothing, and shelter. Unless a family member, foster parent, or institution steps in, the orphan’s survival is in question. These external stakes may continue if the orphan grows up in a hostile environment. Internally though, the orphan faces arguably greater stakes. His or her identity has not been established. In many cases, the orphan protagonist doesn’t know who his or her parents are, where they came from, or how they wanted him or her to grow up. Usually, the only identity an orphan has comes from what others have said or done to shape him or her. This can lead to deep-seated anger and sadness. Yet in fiction, the search for identity and a safe external environment often makes the orphan stronger, more independent, and a better-rounded person. The orphan is easy to root for precisely because he or she is beating huge odds that come from having no parents.

Especially in recent decades, the connotation of the word “orphan” has changed dramatically. What it means to be an orphan can take many forms. However, every modern orphan figure has an important journey at the center of his or her story. Whether an orphaned protagonist is a boy or girl, whether his or her journey involves the magic, the mundane, or something in between, he or she is always on the search for self. In every orphan story throughout the ages, readers have cheered protagonists on as they complete that search.

Fairytale Orphans

Orphan figures populate some of the earliest stories we’re introduced to as children, especially fairytales. From Cinderella to Snow White to Rapunzel, the majority of fairytale protagonists don’t have parents. At best, some protagonists have only one biological parent, usually the father, making them half orphaned. Often, the remaining biological parent dies or leaves at some point. The protagonist is left to fend for herself entirely, even if adults such as stepparents or grandparents are present.This convention is especially popular in older tales, wherein the orphan is almost always a girl and often a princess or noblewoman stripped of her original role. Cinderella is the most famous example, with versions of her story passed down from generation to generation over centuries. Her mother dies early in her life, usually of unknown causes, although some modern adaptations explain the death through illness. Cinderella’s father dotes on her, but feels inadequate. No matter how loving he is, he cannot provide the feminine guidance a mother can, so he seeks a stepmother for his daughter. Unfortunately, Cinderella’s father dies soon after marrying his second wife and bringing her home, along with her two daughters. Some critics of the original Cinderella story and Disney film in particular speculate the stepmother may have killed Cinderella’s father. They cite what author Leighann Morris calls “the war for the inheritance,” and the stepmother’s need to establish herself as head of the household.

As an orphan, Cinderella is also forced into the role of servant. More to the point, she’s a scullery maid, the lowest member of servant hierarchy in her time period. Her stepmother forces her to do difficult, demeaning, and painful work, including scrubbing floors, washing dishes, and tending fireplaces. Cinderella is not the only orphan figure to take on this role. Other orphans, such as Annie from the eponymous musical and Oliver from Oliver Twist, are seen doing menial work meant to emphasize they are the lowest of the low in society’s eyes. Yet Cinderella pioneers the trope. More importantly though, she is the first orphan figure to hold onto nobility in spite of abuse and neglect. The narrator of the 2015 live action remake tells us “her stepmother and stepsisters had transformed her into a creature of ash and toil.” But while Cinderella has her low moments, she never fully embraces the identity thrust on her. She maintains courage, kindness, and selflessness, and these traits are rewarded when she gets a chance to go to the royal ball. Thus, Cinderella becomes the first orphan figure to win readers’ support through her quiet, refined tenacity. Additionally, she is the first to communicate that orphans can make something of themselves and rise above their circumstances even without loving families to nurture them.

As an orphan, Cinderella is also forced into the role of servant. More to the point, she’s a scullery maid, the lowest member of servant hierarchy in her time period. Her stepmother forces her to do difficult, demeaning, and painful work, including scrubbing floors, washing dishes, and tending fireplaces. Cinderella is not the only orphan figure to take on this role. Other orphans, such as Annie from the eponymous musical and Oliver from Oliver Twist, are seen doing menial work meant to emphasize they are the lowest of the low in society’s eyes. Yet Cinderella pioneers the trope. More importantly though, she is the first orphan figure to hold onto nobility in spite of abuse and neglect. The narrator of the 2015 live action remake tells us “her stepmother and stepsisters had transformed her into a creature of ash and toil.” But while Cinderella has her low moments, she never fully embraces the identity thrust on her. She maintains courage, kindness, and selflessness, and these traits are rewarded when she gets a chance to go to the royal ball. Thus, Cinderella becomes the first orphan figure to win readers’ support through her quiet, refined tenacity. Additionally, she is the first to communicate that orphans can make something of themselves and rise above their circumstances even without loving families to nurture them.

Goodness and tenacity alone are not the only things that cause us to root for an orphan, though. While admitting Cinderella’s story is timeless, many critics still malign her as too boring and passive. Sometimes an orphan needs to go on a journey to keep our interest, not just have a wish fulfilled as Cinderella does. Rapunzel is a prime example. In many versions of her story, she isn’t technically an orphan. Her parents are still alive, but were forced to give her up to an evil witch to spare their own lives. Thus, Rapunzel believes she’s an orphan, and her guardian treats her as such. In some versions the witch is neglectful, while in others she couches abuse in a mantle of love. Disney’s retelling, Tangled, has Mother Gothel teach Rapunzel leaving her tower invites nothing but pain and misery. Worse, Mother Gothel consistently tells Rapunzel she isn’t capable of leading a life outside the tower. Yet Rapunzel refuses to believe she is helpless. She longs to see the world and more importantly, find out her strengths. Is she the silly girl worthy of physical and emotional neglect she has been taught she is, or something more? Are her parents and family out there, and even if not, can she find out who she is without them? Rapunzel dares leaving her tower to find out, but it takes more than an encounter with the fairy folk or a wish to provide answers. Most of the time, especially in modern adaptations like Tangled, she must find those answers gradually. Along the way, she meets new people–not just the prince, but citizens of her world–who teach her what the outside is like. She’s faced with tests and travails, including life-threatening pushback from the witch. When Rapunzel reaches the end of her journey and finds out she was always a princess instead of a negligible orphan, we are more than gratified. We feel Rapunzel earned her happy ending because she triumphed through trials, not just at home but in the world around her. Even if, as happens in some versions, Rapunzel doesn’t reunite with her parents, we as readers or viewers know she will be happy because she now knows who she is and why she exists.

Goodness and tenacity alone are not the only things that cause us to root for an orphan, though. While admitting Cinderella’s story is timeless, many critics still malign her as too boring and passive. Sometimes an orphan needs to go on a journey to keep our interest, not just have a wish fulfilled as Cinderella does. Rapunzel is a prime example. In many versions of her story, she isn’t technically an orphan. Her parents are still alive, but were forced to give her up to an evil witch to spare their own lives. Thus, Rapunzel believes she’s an orphan, and her guardian treats her as such. In some versions the witch is neglectful, while in others she couches abuse in a mantle of love. Disney’s retelling, Tangled, has Mother Gothel teach Rapunzel leaving her tower invites nothing but pain and misery. Worse, Mother Gothel consistently tells Rapunzel she isn’t capable of leading a life outside the tower. Yet Rapunzel refuses to believe she is helpless. She longs to see the world and more importantly, find out her strengths. Is she the silly girl worthy of physical and emotional neglect she has been taught she is, or something more? Are her parents and family out there, and even if not, can she find out who she is without them? Rapunzel dares leaving her tower to find out, but it takes more than an encounter with the fairy folk or a wish to provide answers. Most of the time, especially in modern adaptations like Tangled, she must find those answers gradually. Along the way, she meets new people–not just the prince, but citizens of her world–who teach her what the outside is like. She’s faced with tests and travails, including life-threatening pushback from the witch. When Rapunzel reaches the end of her journey and finds out she was always a princess instead of a negligible orphan, we are more than gratified. We feel Rapunzel earned her happy ending because she triumphed through trials, not just at home but in the world around her. Even if, as happens in some versions, Rapunzel doesn’t reunite with her parents, we as readers or viewers know she will be happy because she now knows who she is and why she exists.

Classic Orphans

Centuries after the fairytale orphan, authors began developing what can be called the classic orphan, or orphans present in time-honored literature. Some orphans are embodiments of goodness and patience, almost to the point of sainthood. Oliver Twist, for example, often acts more like a timid girl than a typical boy growing up in the harsh workhouse and street environments of Dickensian London. His grammar is perfect, he embraces Christian virtue with little to no religious training, and he possesses an almost disturbing degree of docility. In many ways, Oliver is a male Cinderella. But plenty of other classic orphans are memorable because they aren’t completely good, and because they possess the vim and spunk to survive in a bleaker world than fairytales present.

Mary Lennox of Frances Hogsdon Burnett’s The Secret Garden is one such classic orphan. She’s the exact opposite of many orphan figures–spoiled, selfish, and as Burnett constantly describes her, “imperious.” Unlike most fairytale orphans, she’s ugly as well. “Her hair was yellow, and her face was yellow…because she was always ill in one way or another,” Burnett explains. Her physical appearance and sour attitude don’t afford Mary much sympathy, even after her parents die and she is sent to live at her uncle’s mysterious, neglected manor. Mary, for her part, doesn’t want sympathy. She expects to be waited on hand and foot, then lashes out at her maid Martha when the servant attempts to fulfill her wishes. She has no social skills; the only children she has ever been around used her as a target for teasing and bullying. Mary is somewhat mature for her age, owing perhaps to orphaned status, but the adults around her see that as more evidence that she’s not a normal child. In one film adaptation of The Secret Garden, it’s said Mary never cried when her parents died. Of course, the girl wasn’t close to her parents, who were self-absorbed and neglectful. Yet rather than placing blame on the parents, the adults in Mary’s life, particularly the housekeeper Mrs. Medlock, imply this wouldn’t have been the case if Mary were an affectionate, cheerful person.

Mary Lennox of Frances Hogsdon Burnett’s The Secret Garden is one such classic orphan. She’s the exact opposite of many orphan figures–spoiled, selfish, and as Burnett constantly describes her, “imperious.” Unlike most fairytale orphans, she’s ugly as well. “Her hair was yellow, and her face was yellow…because she was always ill in one way or another,” Burnett explains. Her physical appearance and sour attitude don’t afford Mary much sympathy, even after her parents die and she is sent to live at her uncle’s mysterious, neglected manor. Mary, for her part, doesn’t want sympathy. She expects to be waited on hand and foot, then lashes out at her maid Martha when the servant attempts to fulfill her wishes. She has no social skills; the only children she has ever been around used her as a target for teasing and bullying. Mary is somewhat mature for her age, owing perhaps to orphaned status, but the adults around her see that as more evidence that she’s not a normal child. In one film adaptation of The Secret Garden, it’s said Mary never cried when her parents died. Of course, the girl wasn’t close to her parents, who were self-absorbed and neglectful. Yet rather than placing blame on the parents, the adults in Mary’s life, particularly the housekeeper Mrs. Medlock, imply this wouldn’t have been the case if Mary were an affectionate, cheerful person.

Near-constant neglect and pigeonholing feed Mary’s bitterness, at least for part of her story. However, being left to herself so much, Mary is more able to strengthen her independence. Her innate desire to have her own way eventually blossoms into determined curiosity, which she needs to survive in an environment where no one will tell her what’s really going on. As she nurtures her secret garden with the help of friends like Dickon Sowerby, Mary’s imperiousness calms down as well. She slowly realizes there are other people in the universe, and they need to learn and grow as she has. When confronted with her bedridden cousin Colin, who is even more disrespectful and spoiled than herself, Mary refuses to let him cow her as everyone else does. “Stop talking to me as if you were a rajah, with emeralds and diamonds and rubies stuck all over you,” she demands once. Later, when Colin has an unprovoked tantrum, Mary shouts, “Stop it! I wish everybody would run out…and let you scream yourself to death!” Her methods err on the harsh side of “tough love,” but they do get Colin to temper his spoiled behavior, hysterics, and hypochondria. Furthermore, being confronted with her own flaws in another person soften Mary so she can act more like a child her age should. Her unconventional personality and dedication to nurturing the garden and Colin although she herself has been shunted aside, change Misselthwaite Manor and the people in it for the better.

Much of classic literature, especially American literature, made improvements on the male orphan, too. Where British literature gave us orphans like Oliver Twist and David Copperfield, American literature gave us spunky, adventurous boys like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. These orphan figures have captivated the imaginations of boys and girls for generations. Barnes and Noble calls them two of their favorite fictional orphans. We aren’t sure what happened to Tom’s parents, but they are never mentioned. He lives with his Aunt Polly, but she is more a prop than a parental figure. As for Huck, he has an abusive, alcoholic father, but that man has little to no influence over his son’s life. Huck does everything he can to avoid him, and Pap Finn eventually dies from his lifestyle’s consequences.

Rather than sending them to orphanages or foster homes, Mark Twain lets Tom and Huck navigate their world primarily on their own. This would have been a radical writing choice when Twain’s books were originally published in the 1870s. Most readers had no concept of children living without adult influence, let alone thriving. Tom and Huck do interact with adults sometimes; the Widow Douglas tries to adopt Huck at one point, and Tom does depend on Aunt Polly for a roof and meals, at least to some extent. However, both boys undertake most of their adventures without adult interference. Tom rarely seeks Aunt Polly’s guidance and Huck, unlike most classic and fairytale orphans, ultimately rejects adoption. The boys’ level of independence grants them opportunities to do things 1870s children, or even modern young readers, might never think of doing. Both boys sneak into the local graveyard one night and witness a murder, and Tom’s testimony saves an innocent man from the hangman’s noose. In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck spends much of the book rafting down a river and helping to free a slave named Jim. The boys also meet casts of colorful characters they might never have encountered under the sheltering wings of doting parents. Their adventures, particularly Huck’s, remain controversial to this day. Yet their books are often one of readers’ first encounters with truly self-determined, independent children who handle tough situations with aplomb.

Rather than sending them to orphanages or foster homes, Mark Twain lets Tom and Huck navigate their world primarily on their own. This would have been a radical writing choice when Twain’s books were originally published in the 1870s. Most readers had no concept of children living without adult influence, let alone thriving. Tom and Huck do interact with adults sometimes; the Widow Douglas tries to adopt Huck at one point, and Tom does depend on Aunt Polly for a roof and meals, at least to some extent. However, both boys undertake most of their adventures without adult interference. Tom rarely seeks Aunt Polly’s guidance and Huck, unlike most classic and fairytale orphans, ultimately rejects adoption. The boys’ level of independence grants them opportunities to do things 1870s children, or even modern young readers, might never think of doing. Both boys sneak into the local graveyard one night and witness a murder, and Tom’s testimony saves an innocent man from the hangman’s noose. In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck spends much of the book rafting down a river and helping to free a slave named Jim. The boys also meet casts of colorful characters they might never have encountered under the sheltering wings of doting parents. Their adventures, particularly Huck’s, remain controversial to this day. Yet their books are often one of readers’ first encounters with truly self-determined, independent children who handle tough situations with aplomb.

Modern Orphans

Orphans heavily populated nineteenth and early twentieth century literature due to the lack of medical advancement and high mortality rates in those eras. As medical science advanced, parents’ chances of staying alive past their offspring’s early childhood improved dramatically. However, orphan figures remain popular in modern literature–the face and situation of the orphan has simply changed again. Not all orphans are orphans in the truest sense, and not all their exploits are confined to the modern world as readers know it. Some are essentially “good” or “nice” kids, while others have rough edges or are downright rebellious. While most orphan figures seek home and family as an ultimate goal, the realization of that goal looks drastically different than it did in the 1830s, 1870s, or 1910s.

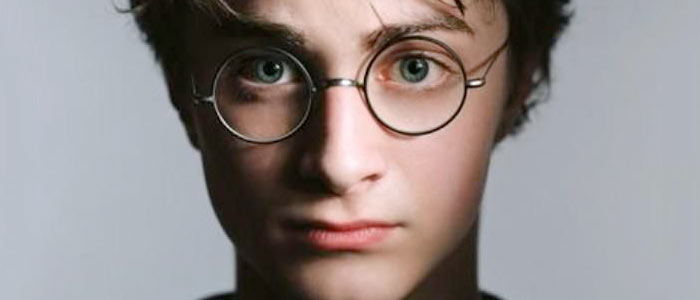

Perhaps the most popular fictional orphan of today is Harry Potter. Like many classic orphans, he lives under what TV Tropes calls “Cinderella Circumstances,” but unlike classic orphans, he doesn’t grow up in a cold orphanage or sadistic foster home. The people who torment Harry are his aunt, uncle, and horrifically spoiled cousin Dudley. They force him to live in a cupboard under their stairs, barely feed him, and work him like a slave. Dudley is afforded every opportunity life has to offer, like an exclusive education, rich foods, and piles of presents. Uncle Vernon and Aunt Petunia plan to pack Harry off to the local state school, and would never dream of providing him anything but the bare minimum. Harry eventually escapes this miserable life to craft his own identity and find adventure. Yet he doesn’t do it with the help of a Daddy Warbucks-style adoptive parent, or even through running away. It turns out Harry is a wizard, born to magical parents of whom his aunt and uncle were ashamed. When Harry turns eleven, he receives his letter of acceptance to Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, and begins embracing his true identity as a strong, independent, and magical person. Additionally, he’s given an opportunity Dudley will never have–the opportunity to fight for the greater good in his realm and ours.

Once Harry arrives at Hogwarts, he experiences things he never dreamed of, such as true friendships with students like Ron Weasley, Hermione Granger, Neville Longbottom, and Luna Lovegood. He’s embraced as a member of the school’s family; actually, he’s lauded as a sort of celebrity because he lived through the evil wizard Lord Voldemort’s attack on his parents. Teachers like Dumbledore and McGonogall provide Harry much-needed mentorship. Thus, Harry’s basic needs are finally met, and his self-esteem gets a much-needed boost. Once that foundation is laid, he can focus on delineating between good and evil and deciding which one he will be.

Throughout the seven books featuring him, Harry is often tempted to take actions that would push him toward the dark side of magic. Sometimes he gives in, such as when he uses magic outside Hogwarts, against school policy, to deal with bullies. Harry Potter is a refreshingly imperfect, modern, and real character. Yet he always ultimately returns to the side of good, remembering one of Dumbledore’s first lessons. “It is our choices that make us, not our abilities,” Dumbledore tells Harry at one early point. In making those choices, Harry shapes himself and the world around him in a way few orphans before him ever could. His negative choices expose his weaknesses and set him back in his mission to defeat Voldemort and save his beloved school. On the other hand, his positive choices take him from a gawky, browbeaten boy to a courageous young leader worthy of his title, The Boy Who Lived. He earns the title not only because he lives through Voldemort’s attacks, but because he lives a full and memorable life, despite bleak beginnings. His epic adventure teaches readers that whether they’re orphans or not, they too can make the choices that will help them change the world, although it may be a small corner of the world. Although those readers don’t have magic at their disposal, Harry shows them they do have the traits Hogwarts and the series characters hold dear, such as courage, intelligence, compassion, and a sense of justice.

Modern literature hasn’t skimped on the female orphan, either. Arguably, female orphans are more popular now than ever. They are stronger, more multifaceted characters than they were in the days of Cinderella, Mary Lennox, and other classic or fairytale orphans such as Rapunzel, Sara Crewe, or Anne Shirley. In part, modern female orphans’ popularity stems from their unique situations and the unique lessons that come from them. In older stories, female orphans were far less likely than males to act adventurous, rebel, run away, or be anything other than the typical female. Female orphans were more likely to be adopted into happy, often wealthy, families, or raised in a privileged environment like Mary Lennox or Sara Crewe. If they faced travails, those were likely in the form of Cinderella circumstances, whether the girls were forced to work in an orphanage, boarding school, foster home, or other institution. Like their male counterparts, today’s female orphans are rarely institutionalized. They might perform hard labor, or what they see as such, but it’s rarely their biggest problem. Modern female orphans are often spunky, rough-edged and rebellious, tomboyish, gifted, or feminine without being stereotypically so. They are independent, tenacious, and determined to secure good futures for themselves.

One such female orphan is Galadriel “Gilly” Hopkins of Katherine Patterson’s The Great Gilly Hopkins. Although Patterson’s book was first published in 1978, it continues striking chords with modern readers. Recently, the novel was made into a motion picture. In the novel and film, Gilly is a foster child who’s been shuttled from one home to another. Most of her foster parents were what her social worker calls “nice,” but they made excuses to send Gilly back into the system, or could not handle her attitude. Gilly is brilliant and funny, but blunt and difficult to control. She apparently possesses no social filter; some of her brutally honest assessments of the world around her cross into the offensive. When she’s sent to live with Mamie Trotter in the Thompson Park neighborhood, Gilly thinks she’s landed in the worst foster home yet. Mamie is not a typical foster mom; she’s obese, dresses in shabby clothing, and often makes religious remarks. Gilly suspects William Ernest, the other foster child, of mental retardation, and she finds Mamie Trotter’s dusty, messy house appalling. In stating these things, she hopes Trotter, as the foster mother prefers to be called, will send her back, but Trotter isn’t one to give up. Interestingly, neither is tenacious Gilly.

One such female orphan is Galadriel “Gilly” Hopkins of Katherine Patterson’s The Great Gilly Hopkins. Although Patterson’s book was first published in 1978, it continues striking chords with modern readers. Recently, the novel was made into a motion picture. In the novel and film, Gilly is a foster child who’s been shuttled from one home to another. Most of her foster parents were what her social worker calls “nice,” but they made excuses to send Gilly back into the system, or could not handle her attitude. Gilly is brilliant and funny, but blunt and difficult to control. She apparently possesses no social filter; some of her brutally honest assessments of the world around her cross into the offensive. When she’s sent to live with Mamie Trotter in the Thompson Park neighborhood, Gilly thinks she’s landed in the worst foster home yet. Mamie is not a typical foster mom; she’s obese, dresses in shabby clothing, and often makes religious remarks. Gilly suspects William Ernest, the other foster child, of mental retardation, and she finds Mamie Trotter’s dusty, messy house appalling. In stating these things, she hopes Trotter, as the foster mother prefers to be called, will send her back, but Trotter isn’t one to give up. Interestingly, neither is tenacious Gilly.

Gilly sets herself apart from fairytale and classic female orphans in a few key ways. First, she isn’t what readers normally consider a “good” kid, but she wants to be. She calls herself Gruesome Gilly, but sees in herself the potential to be “gracious, good, glorious Galadriel.” Yet Gilly can’t risk trading one identity for the other because if she did, she might get attached to the people of her new foster home and school. She can’t afford attachments, because unlike the other orphans we’ve discussed, Gilly still has a parent. She hasn’t seen her mother Courtney since she was a baby, but believes if Courtney came to claim her, she would lead a perfect life. Gilly’s situation modernizes what it means to be an orphan in one of the biggest ways imaginable. Today, being an orphan doesn’t necessarily mean having no parents. It can mean having an inadequate or absent parent, and longing for a relationship with that adult. Gilly is far more of an emotional orphan than a physical one, which makes her more sympathetic to readers and raises her story’s stakes. Readers stick with Gilly’s story because they want to know where she will find true love, nurturing, and relationships. Will the fantasy of life with Mom come true, or will she be challenged to choose her own family?

For Gilly, the answer is “both.” Her pain and anger eventually drive her to write a letter full of lies to her mother Courtney. In it, she basically claims she is in an abusive situation and expected to care for everyone in Trotter’s house. In a callback to classic female orphan-hood, she sets herself up as Cinderella. Gilly’s grandmother comes to Trotter’s to assess the situation, but unfortunately, she arrives when everyone except Gilly is sick with the flu. What Gilly wrote looks true, and so her grandmother takes Gilly away to live with her. By then, though, Gilly has formed attachments to Trotter, William Ernest, her teacher Ms. Harris, and a friend named Agnes, in spite of herself. In the film version, she begs her social worker to intervene and let her stay at Trotter’s. “I lied; none of it’s true,” she pleads. However, because of the way the foster system works, Gilly must face the consequences of her actions. Although she’s able to form a happy life with her grandmother, called Nonnie, she eventually learns her mother does not want her. Saddened and angered yet again, Gilly begs Trotter to let her come “home.” Trotter explains this isn’t possible, but she and the other Thompson Park residents continue as Gilly’s support system from a distance. They, along with Nonnie, make up the family Gilly ultimately chooses for herself. That family isn’t perfect, but it is what Gilly needs. In choosing it, Gilly sends one more modern message about orphan-hood. There may never be a perfect adoption or perfect family at the end of an orphan’s journey, but that isn’t important. The importance of the orphan’s journey, and the reason readers like encountering orphans, lies in the lessons they learn and the decisions they make for themselves.

The Final Verdict

Orphans have populated children’s and young adult literature for centuries, and are among the most popular protagonists for both genres. In times past, they were popular for their virtue and the pathos they evoked in readers. But the face and journey of the orphan figure have changed. A child without parents, or with inadequate parents, will usually evoke pathos. Yet today, orphans are smart, independent, tough kids readers easily root for. They may not have asked for the autonomy thrust upon them, but they often use it to become someone they never imagined they could be. The world and people around them are often better for that, as are readers.

Works Cited

Burnett, Frances Hogsdon. The Secret Garden. Collins Classics: Reprint Edition, April 1, 2010.

“Cinderella Circumstances.” TV Tropes. http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/CinderellaCircumstances

Paterson, Katherine. The Great Gilly Hopkins. HarperCollins Publishing: Reprint Edition, April 13, 2004.

Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. Scholastic Publishing: September, 1998.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

I think a reason that YA protagonists tend to lack a set of present, caring parents is that it makes the plot a LOT easier if there isn’t constantly a parent breathing down their back asking them what they’re doing and where they’re going.

Like, let’s be real. If that 16-year-old had responsible, watchful parents, she would NOT be able to spend every evening out fighting evil or practicing her new-found powers with her rebellious emo love interest. That situation in which she almost died fighting off some powerful creature but finally managed to rid the world of its evil? Yeah, if she had concerned parents, that never would have happened, because she would have been at home grounded for sneaking out the past two weeks.

Unless, of course, the parents are in the know as well. Then things get a lot simpler. But I do think that one reason they are not often present is because having them there would make things a lot more complicated.

So if you want to have the protagonist in a “whole” family, I think the real challenge is in figuring out what role the parents play. Why do you need them in your plot, and how does having them present affect your character’s story?

I’ll admit, I took the lazy way out myself. No parents present for the majority of my novel XD heh.

I kinda like having the unbroken home because it adds the conflict of “live a normal life and get your homework done” to their chosen “fight evil and save the world” lifestyle. You can always end a book with the MC getting grounded forever.

It is easier and more fun to get rid of the parents though, it also give the MC something that is missing in their life which you can always fill with the wise old man archetype. Before you remove him/her of course.

This made me think of Buffy.

What I’ve always wondered: What the heck is going on with Star Trek: The Next Generation? Almost every backstory for the characters involves dead parents. And it really was just backstory, outside of Worf, being an orphan or raised by a widowed parent wasn’t important to their story. Like Frodo being an orphan isn’t weird, but it would’ve been odd if the whole company was orphans and there wasn’t an orphanage involved.

Being orphaned is usually why they are so independent, reckless and determined.

It gives the character instant sympathy, a motivation to build off and they have so much more freedom. Much harder to have a parent in tow for all of it (though if done right, that could be an interesting idea).

Especially parents being in charge.

A very interesting take on this fascination with orphan protagonists. When I was young we used to read so many novels about kids in boarding school. Somehow the absence of parents make everything so much more mysterious.

I read the Boxcar Children and the ending of the series happened when the kids went to live with their rich uncle.

I do not think that the orphan motif is going away any time soon. Look at Orphan Black.

Writers, maybe don’t make your protagonist a kid. You only need to murder off the parents to prod a juvenile out of the safety and security of home. Put the character into their adult years, and allow him/her to act with agency instead of being forced into action.

That’s a great idea, although it changes the audience (which isn’t a bad thing at all). In fact, adults who grew up as orphans but have since established themselves are some of the most sympathetic characters out there. Emma Swan is a personal favorite of mine, but there are plenty of others.

I think, in many cases, it boils down to the “destined for greater things” trope. If the protagonist grows up knowing who their parents are, then you won’t get that “twist” when they turn out to be royalty/wizard/alien/jedi etc.

It does, although personally I’d like to see more orphans who *don’t* turn out to be royalty or have special powers. Not that those books aren’t cool, but the majority of readers don’t live that kind of life, orphan or not. Myself, I always liked it when for a change of pace, a character went to school, hung out with friends, joined clubs, etc. If they happened to save the world in the process well, that was just a bonus.

Protagonists also tend to be friendless, childless, and unmarried. These people are completely unattached, and that allows them to go places and take risks that would be out of the question for more settled types.

It also makes for great character development when protagonists gain friends and allies along the way.

Great article. I’d never thought about so many characters being orphans.

A lot of stories with orphan kids are set in pre-modern worlds and in our own world that would imply a high chance of one or both parents dying young. You see it a lot in 19th century lit as well eg. Jane Eyre, Heathcliff.

Not sure what world you’re talking about, but it isn’t ours. Throughout most of history if you survived past childhood you had a pretty damn good chance to making it to at least 50. Obviously you still had a pretty good chance of getting caught up in a war and killed that way but the whole myth of life expectancy comes out of the average life span statistic which is brought down by death of infants and children, not adults dying young.

I see your point, but I think you’re forgetting a few things. Most notable is the lack of medical advancement (plagues of influenza, typhus, cholera, and etc., anyone)? But even if your parents didn’t succumb to disease, you had a high chance of losing them as a historical child. For instance, many lower-class parents abandoned their children because they couldn’t care for them, or sent them to orphanages (see the orphan trains of the 1800-1900s.)

There are also documented cases of children being stolen from their parents throughout history. Check out the horror stories of Georgia Tann and the Tennessee Children’s Home Society of Memphis. So yeah, overall decent life expectancy–but much higher chances of enduring adult-size ordeals as a kid.

Death in childbirth was far more prevalent than it is now, as well as many little things like a staph infection that could kill someone which we now treat easily. Personally, my parents would have both been dead (multiple times) before I was 20 without modern medicine. I’m aware that infant mortality drags down the average, but that doesn’t mean that there wouldn’t be a very high (compared to now) number of people that had lost one or both parents.

@Suk: Absolutely, the unattached nature of orphan-hood gives protagonists a lot more freedom, which I think modern writers are eager to explore. Being an orphan used to = being pitiful and victimized, but now it often means the chance to form your own sense of self outside what adults tell you, you should be. Whether that actually *glamorizes* the raw reality of being an orphan is up for debate.

Orphans are awesome narrative tools. They have no ties to keep them in the Shire/Dale/Homestead/Tatooine. They have a motivation for adventure, perhaps a mystery to solve or revenge to seek. It’s a great short cut. Overused. Easily abused. BUT, when it works… 🙂

…It really works. You’re right, though, about the orphan trope being overused, esp. in our current society. These days, I see more children’s, tween, and YA literature whose protagonists have fractured or non-traditional families. Sometimes the protagonists are fine with that, and sometimes it leads to their character journeys. Either way, diverse family structures may be edging out orphan stories on some level, which can be a great thing.

Most of these stories are about teen protagonists, and being orphaned is another obstacle to overcome.

A while back I wrote a teen character whose parents were alive and ran headlong into exactly this issue. In order to allow anything to happen the way I wanted, they had to hate their parents and be willing to give them the finger even if they weren’t leaving home. I didn’t necessarily want this but nothing else made for a compelling plot or character given the story I had.

That does not mean that characters with parents are not workable but parents have to add something to the story, which may often dictate how a plotline evolves. Write a character with parents but then categorically ignore them and the character (or the story, often both) suffers as a result as it feels… cold, almost indifferent. That can work too but it’s usually not the intended effect.

The reasons for this actually go a bit deeper than just starting conflict or being boring baggage tacked on the story. We as readers are human. Parents or parent figures are a huge part of our lives. We inherently view them as ‘family’ and ‘close’ and any person (or character) who does not is immediately cold, almost evil… at best misunderstood. A character intended to explore a world (as is often the case in fantasy) needs to be free of those ties, usually without the negative connotations.

Even without the revenge angle, or the boring plot baggage angle, having a character who does not appear disloyal to family and community for ‘going away’ is powerful. For lawful good (or any good aligned) characters it’s almost a necessity. A good character carrying around a ‘but I ran away from my parents’ secret with them is always going to be harboring a dark secret. It’s an implicit judgement of character we all make, both as author and reader, without thinking about it.

A child raised with two loving parents in a decent household needs some conflict or drama to get them out of that situation.

a orphan from a good and caring orphanage wont grow up to be a superhero or a revolutionist or a murderer. no one makes stories about the happy ones who grow up, find a loving family and lives a normal life.

Unless that loving step-family is killed, starting the heros journey. Like StarWars for example.

Authors find it much easier to have child main characters who have no parents to tell them “don’t do that”. Would be a very boring book otherwise.

Indeed. Which is why, in the comics of my youth, so many of the central characters were boarding school pupils. It was a convenient way of removing parents from the scene. Others involved boys whose mothers were dead and whose fathers had gone missing in South America or elsewhere. It’s just not easy to have adventures while at home with ones parents.

Well, they have no parent to tell them to go to bed instead of hunting dragons, learning magic, or attending the insurance nightmare that is Hogwarts.

Orphans are really common in regency/Victorian literature, it just sets things up for some good ole Bildungsroman.

It was interesting what Meyer did in Twilight. Bella has both parents but the mother is an absentee mother and the father is clueless. His role as guardian is used to good effect, though, as it forces Bella to become creative in her relationship with the supernatural. Without Charlie breathing down her neck or being hostile to Edward, a lot of the drama would be lost.

At the same time, Bella is a precocious 17 year old. She looks after her parents and so the roles have been somewhat reversed. She stands up to her father with no problem. I guess, in effect, that makes her an orphan figure.

Very good article!

The literature of worldwide is full of stories of orphans as heroes with very spiritual and cultural heritage of protection.

Great article! I especially liked where you pointed out how orphans differ in British and American literature.

@Kenneth: Would you believe I didn’t set out to make that comparison? It’s just that I noticed all my “classic” orphans tended to be British, while the “modern” ones tended to be American (with the exception of Harry Potter, who is English, but since his franchise is such a hit in both countries I’d almost call him a crossover).

Now I wish I had discussed that particular difference in more detail. Britain tends to give their orphans different obstacles, personalities, etc. than America does, or at least that’s the way it used to be. (Mary Lennox, Oliver Twist, Huck Finn, and etc. are so far apart in personality it’s not even funny). That may be because of the way Britain and American raise their children, instill particular values, or extol different traits.

This is a really good article Stephanie.

I love YA and I hand’t made the connection that most of my favourite books had orphaned protagonists. I agree with the comments above, that parents do tend to “get in the way of adventure”. Your comment about even sometimes having one parent has an effect is also true.

Modern characters such as Katniss Everdeen from Hunger Games is an example. Her mother was depressed after her father had passed and Katniss had to grow up and become a mother to her sister for their survival. This key bond might have been the only reason Kat felt she had to volunteer as tribute to save her sister, which made the public admire her from the beginning.

Game of Thrones – The Stark children had loving parents at the beginning, but after the brutal death of Ned (and later their mother) all children rallied against their enemies in their own way.

So many examples…definitely made me rethink about a few of my favourite characters.

Abby

Hi, Abby–glad to know you enjoyed the article.

Your comment makes me wish I could have spent more time on orphans who actually have parents, except that those parents are absent/inadequate/abusive, what have you. (In actuality, I probably would’ve been told such an article was way too long; it could’ve been a separate topic in itself).

I’ve noticed this trend a lot in modern middle grade, teen, and YA novels, movies, and franchises. It often works even better than the traditional orphan story, because the parents don’t get in the way, but they still have significant influence. The question becomes, is it easier to grow up with no parents, or with existing parents who didn’t step up like they should’ve? There are definite pros and cons. With dead parents, you can imagine that they were perfect, adored you but couldn’t stick around, etc. With an inadequate parent you can’t do that, but you can use their successes and failures to inform who you will become. The possibilities are endless.

A wonderful article. I’ve always found the orphan figure interesting.

Great Article!

I definitely think that by creating orphan characters, authors have a ready-to-use damaged character, with a viable excuse for their particular flaws (apart from just being human, of course).

Very insightful article on a literary topic I’ve never thought of before. You were very thorough with providing evidence for your claims. I really would like to read or watch The Great Gilly Hopkins now too.

The book is always better. 🙂 I’d start there.

I think my favourite orphans are Annie, Oliver, and Harry Potter is probably the most known orphan around the world. I love ya, fairytales so this was great.

In a sense, the Harry Potter story begins with a Deus Ex Machina, in that his life path, particularly in the beginning is bequeathed to him completely by chance.