The Rise and Fall of the Narnia Film Series

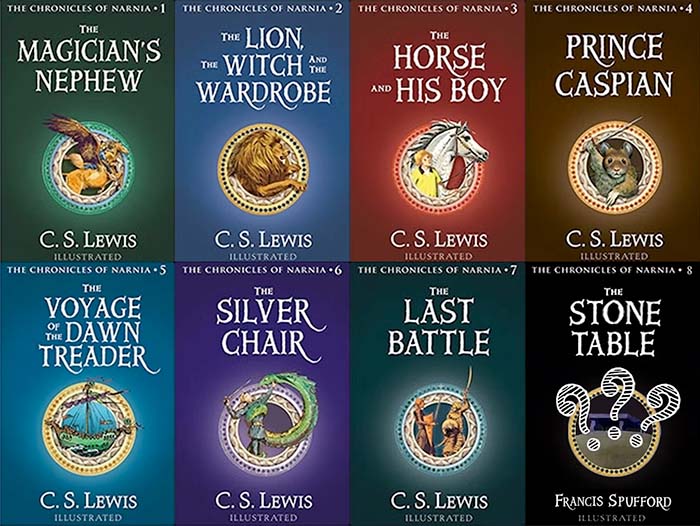

Between 1950 and 1956, Clive Staples (C.S.) Lewis published his famous Chronicles of Narnia septet. Partially based on Lewis’ own experiences during World War II, during which he and his older brother Warnie took in some of London’s child evacuees, the septet has never been out of print since. The books are often sold as a complete set or omnibus and have inspired reams of scholarly works including full books, peer-reviewed articles, and amateur literary criticism from fans and detractors alike.

As happens with many books of Narnia’s caliber, Lewis’ series has also received the film treatment. The first Narnia film was a 1979 British production of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, an animated project that interestingly featured American voice actors. That project fell into obscurity fairly quickly. It has something of a cult following among those who saw it as children, but even that audience is smaller than the phrase “cult classic” connotes. Other Narnia films, radio productions, and other media exist, but it would be just under 30 years before the land of Narnia got another big chance to be brought to life on the silver screen. Unfortunately, the series would fall again almost as quickly as it rose back to fame.

The three Narnia films that do exist were successful, and their fanbase still questions what happened to the franchise. That fanbase also wonders if the films, and Narnia itself, could ever achieve the success they feel it deserves, finding niches similar to those of Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, or even Twilight or the Percy Jackson films. Meanwhile, detractors insist Narnia is dead in the water if it ever had a chance in the first place. They claim by its nature Narnia, the world itself, the books, and the films, was never going to be on par with any of its competing fantasy franchises. Furthermore, it will never become so, no matter how many generations of children grow up loving the books and the existing films and other media.

With a retooled Narnia television series slated for Netflix later this year, as well as rumors of The Silver Chair receiving a film, it is appropriate for Narnia to reenter the conversations surrounding fantasy-based media and fantasy worlds in general. It’s also vital that Narnia reenter these conversations since that world was one of the first and oldest to capture the imaginations of children and maintain “crossover” adult appeal. However, most of Narnia’s supporters have been quiet on social media since these developments were announced. Furthermore, many supporters are already defaming the Netflix series and new film because they will be radically different from the other three films. Thus, both detractors and a large subset of fans seem to agree Narnia has no chance of resurrection.

As with all matters of fandom, it’s impossible to say who is “right.” However, it is well worth examining who and what breathed life into the Narnia franchise to begin with, as well as how that life was lost. Once we’ve done so, we can examine whether any life remains in existing Narnia media or the interest of its fans. If yes, the question becomes where that life exists, and what old and new fans can and should do with it. Once those questions are answered, those old and new fans can decide what a new or “resurrected” Narnia might look like.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe: The “Birth” of Narnia

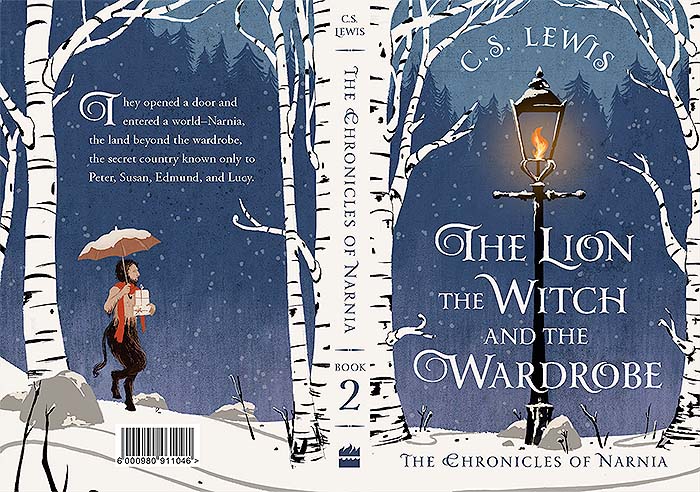

Despite arguments from some purists that The Magician’s Nephew should be read first, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (LWW) is largely considered the first Narnia installment. Walden Media treated it as such, and it was the first film to grace theaters, coming out on December 7, 2005. Coupling the story’s wintry setting and themes with a holiday release date ensured moviegoers would be in the proper mood for a story Screen Rant wrote had all the “whimsy, magic, and excitement of a fantasy movie.” Indeed, LWW “cleaned up” at the box office, grossing about $745 million and becoming the 52nd-highest grossing film of all time. But it wasn’t just raw numbers or wintry “whimsy” that made this first Narnia installment the charming, endearing, and memorable film it was then and remains now. This debut film holds the most depth, relatability, and “life” of any in the Narnia trilogy. Its verve can be credited to its main characters, four relatable, three-dimensional kids with great character arcs inside a big, multifaceted story.

Relatable, Growing Heroes

The first people viewers meet in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe are the Pevensie children, Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy (William Moseley, Anna Popplewell, Skandar Keynes, and Georgie Henley). We first see them running for their home’s bomb shelter during a Blitzkrieg air raid. This cuts to a scene at a London train station, where Mum is sending them off to a safe but strange house in the country. The kids will presumably stay there until the end of the war, and as Edmund says, home may not be there when and if they can return to London. Peter and Susan, at least, must admit he’s right.

As moving and disturbing as their external stakes are, it is not their externals that make audiences stick with the Pevensies. Rather, viewers stick with the Pevensie children because they are children. They have room to grow, learn, and develop. They have no control over the war their country is fighting, but they can adapt, find adventure, and fight good and evil on their own terms. As Peter tells Lucy, “We can do whatever we want here. Tomorrow’s going to be great.” As C.S. Lewis said, “Since it is likely that children will meet cruel enemies, at least let them have heard of brave knights and heroic courage.” Modern viewers root for the Pevensie kids, who have already lived through war, to find such courage–and once they find it, learn how to use it.

The “learning” part of the journey, the relatability, is why viewers invest in the growth of our heroes. It’s clear early on that Lucy Peter, and Susan, will eventually “be on the side of the Faun and all the animals,” while [Edmund will be] more than half on the side of the Witch,” as the original book explains. Viewers could easily write off Edmund and Lucy as cardboard child characters, simplistic lessons in obedience vs. disobedience. Similarly, viewers could neglect Peter and Susan as older siblings who have already learned their lessons in virtue and tag along to ensure their little sister and brother don’t get into trouble. However, director Andrew Adamson and producer Douglas Gresham are not about to let viewers become so complacent, or let the Pevensies become so boring.

The film’s dedication to character turned out to be its biggest strength. Analysts and fans like The Thrifty Typewriter still praise LWW’s “active characters” as standouts in the fantasy genre, wherein intense world-building and battles of good and evil tend to make “pinballs” of the protagonists (figures with little to no agency and no purpose except being acted on by the plot). Within the first 12 minutes of the film, viewers are more than ready to follow all four Pevensies through the wardrobe and through two hours of character growth.

Four Children, Four Journeys

Lucy: Littlest Sister, Truest Believer

Each Pevensie child receives an arc that challenges them at their cores. Lucy’s is arguably the simplest. She is most open to Narnia and takes everything at face value. For instance, she trusts Mr. Tumnus almost the moment he offers a friendly face, warm fire, and cup of tea (with sardines “by the bucketload,” we cannot forget). Lucy is instantly empathetic and forgiving toward Tumnus when she learns that, though the White Witch hired him to kidnap her, he feels guilty for doing so and wants to let her go. She even invites Tumnus to keep her handkerchief, explaining, “You need it more than I do.”

Compassion Beyond Her Years

We could put this down to Lucy being the youngest and most idealistic Pevensie, and we’d be partially right. Yet, Lucy’s depth of empathy continues throughout the film. When all four Pevensie siblings return to Narnia and discover Tumnus has been captured, Lucy is devastated and instantly blames herself–“[The Witch] must’ve found out he helped me!” She insists the siblings must stay and help the Narnians, no matter the personal danger to themselves.

Lucy isn’t showing the impetuousness common to a youngest child. She maintains her determination despite how difficult the journey becomes. In fact, she becomes braver the more obstacles she encounters. A fall through thawing ice leaves her soaked, cold, and shaken, but undeterred and more concerned that her siblings are okay. Perhaps in line with this “healing instinct,” Lucy is the sibling upon whom Father Christmas bestows the healing juice of the fire flower. She is the first to forgive Edmund for his betrayal, and sticks closest to him after the fact, making sure he’s physically healing (“Narnia’s not going to run out of toast, Ed.”) When Edmund is injured in the final battle, Lucy arrives in seconds, her vial of fire flower juice at the ready. Since Edmund’s wound is mortal, Lucy’s quick feet and thinking, and her deft delivery of the medicine, save both his life and the Narnian prophecy of four new royals.

A Heart Filled with Faith

Finally, throughout LWW, Lucy is emotionally closest to Aslan. His presence awes her more than any of the other siblings; she takes to heart the adage, “He’s not safe, but he’s good.” She puts total faith in Aslan to help the captive Edmund and defeat the White Witch, and his sacrificial death reduces her to heartbroken sobs that last all night. Lucy actually tries to use her fire flower juice on Aslan’s wounds, only stopping when Susan tenderly says, “It’s too late.” Some scholars who compare Edmund to Judas Iscariot likewise compare Lucy to Mary Magdalene at Jesus’ tomb. (Susan is sometimes given this comparison but could also be another disciple). No matter who else the other Pevensies are, the comparison to Mary Magdalene fits Lucy best. As Mary was Christ’s most devoted female follower, Lucy is Aslan’s. She seeks to please him always, and had LWW gone this direction, she might have volunteered to lay down her life for him at some point.

Lucy’s joy at Aslan’s resurrection is palpable. The book describes her jumping onto Aslan’s back and enjoying the ride into Narnia, and the film shows this in wonderful detail. Later on, after her crowning as Queen Lucy the Valiant, she is the last to turn away from Cair Paravel’s windows as Aslan walks away. She’s quietly weeping, and Tumnus comforts her with the handkerchief she once gave him and the same line, “You need it more than I do.” He comforts Lucy further with the reassurance, “One day he’ll be here, and the next he won’t,” but Aslan is always around. This steels Lucy’s already strong faith, cementing it for the stories to come. Her character arc ends on a note that shows viewers she has grown from the little sister who needs the most protection, to the sister who can remind the others of the simplicity, yet importance, of their purpose and beliefs when needed.

Edmund: Selfish Traitor to Steadfast Hero

Similarly, Edmund’s character arc looks obvious, but is layered. His is the most allegorical, hearkening back to the sinner’s journey toward faith in Christ. Several tangible parallels exist between Edmund, an eventual “believer” in Aslan, and an average convert to Christ. The Turkish Delight the White Witch plies Edmund with is a stand-in for the forbidden fruit that caused Adam and Eve’s original sin. Edmund becomes a Judas Iscariot figure when he sneaks out of the Beavers’ home in search of the White Witch’s castle, hoping to turn in his siblings to her for more “sweeties.” And, as Christ’s blood stood in for the blood of real sinners at the crucifixion, fulfilling Biblical law, Aslan makes clear his blood will substitute for Edmund’s and fulfill the “Deep Magic.” Yet, these parallels do not complete Edmund’s character arc.

The movie makes clear Edmund’s behavior is understandable, especially considering his trauma. Edmund is in no way a “bad” kid. In fact, fans like The Thrifty Typewriter and Friendly Space Ninja admit sympathy for him, often based on being a middle child or younger sibling themselves. But Adamson, Gresham, and C.S. Lewis also make clear, Edmund is old enough to know when he’s hurt someone else. He’s old enough to begin learning the world does not revolve around him. Herein lies Edmund’s character arc. He can become a hero and earn the title King Edmund the Just. Yet he can only do so once he understands where selfishness and greed, taken to their final ends, land someone’s soul, and how the consequences can affect innocent bystanders.

Edmund gets two quick, jarring lessons in consequences when he goes to Narnia with his siblings and sneaks out of dinner with the Beavers to find the White Witch’s house again. Edmund is determined to find the White Witch and cash in on her promise that he will be a prince of Narnia with his own palace, complete with “whole rooms simply stuffed with Turkish Delight.” Instead, he finds a White Witch incensed that he came to her castle alone, Lucy’s Faun friend Tumnus chained in a dungeon, and himself a captive of evil incarnate. Edmund watches the Witch turn Tumnus and others to stone, thereby “killing” them. His arrogance, insecurity, and greed are prime examples of what the Bible calls “sin [giving] birth to death.”

Real Redemption in a Fictional Package

In C.S. Lewis’ world, there is no death without a chance at rebirth. Aslan offers Edmund that chance. “Do not cite the Deep Magic to me, Witch,” he warns with a roar in his voice when the Witch points out, “Every traitor belongs to me.” Aslan, as the writer of the Deep Magic, can do what Edmund, a human child and the representation of human viewers, cannot. After a private meeting with the Witch, he announces, “She has renounced her claim on the Son of Adam’s blood,” and dies on the Stone Table before all Narnia. As a representation of Jesus Christ crucified, Aslan also endures myriad humiliations before death. These include being insulted, tied up, spat on, and shaved. Aslan is truly dead before the scene fades to black. There’s no chance he is in a coma or has been rescued last minute, and his blood has wiped Edmund’s record clean.

Edmund’s character arc doesn’t finish until Aslan’s resurrection. This is the pinnacle of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and of the story of the Christian Messiah C.S. Lewis sought to make accessible to children. On a smaller scale for Edmund and every reader though, it’s the pinnacle of an individual story. It’s the triumphant end of how one child deals with his personal sins and moves forward into the rest of his story. Once Aslan returns to life and raises his army, he and Edmund have a private moment. Viewers don’t hear what they say, but we see them alone on a hill, a warm sunset backlighting them. Edmund’s body language speaks humility, while Aslan’s is serious, yet tender. Edmund returns to his family looking simultaneously burdened and at peace. Aslan cuts off any curiosity with a simple, “What’s done is done. There is no need to speak to Edmund about what is past.”

A King Rises from the Ashes

Indeed, Edmund’s betrayal is never directly addressed again, and Edmund doesn’t show signs of trauma or being “stuck” in the past. Edmund knows though, he can’t move forward without dealing with the past. When Peter tells Edmund he’ll stay behind to fight the Witch while Edmund takes his sisters home to safety, the younger Pevensie vetoes the plan. “I’ve seen what the White Witch can do, and I’ve helped her do it. We have to stay,” he says, eyes full of hard-won wisdom.

The regret in his tone reveals this isn’t about redemption. Edmund understands Aslan took care of that. For the first time, Edmund wants to put others first. He knows what real loss and grief feel like and understands what and who are worth fighting for–read: family, love, and faith, not material possessions and carte blanche to fulfill petty desires. He has not yet been crowned, but is preparing for his role as King Edmund the Just.

Edmund proves himself many times in the film’s final battle. He takes several hits, one potentially mortal. However, it is his smaller actions that prove him “kingly.” For instance, he relates well to all his fellow soldiers, no matter their species, and treats them as comrades. He sticks close to Peter throughout and is first to both help his brother and follow the older boy’s orders. If and when Edmund doesn’t “do as he’s told,” this time, it’s to keep his siblings out of the fire line. Perhaps most cheer-worthy, Edmund is cagey about facing the White Witch, but does not shrink back when she appears on the front lines. He doesn’t fight her one-on-one or strike a fatal blow, but his courage stands out. Edmund’s final stand against the Witch reads much more as something he does for Narnia than for his own sense of bravery. It completes his transformation into the respected, praiseworthy hero he wanted to be in the first place.

Peter: Growing Man With a Lion’s Heart

Though he would’ve denied it for much of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the person Edmund always wanted to be was a person like his older brother Peter. Peter, played by William Moseley, looks like the quintessential Cool Big Bro, as TV Tropes would call him. According to literature such as the NarniaFans forum, HomeworkStudy.com, and SparkNotes, Peter is about 13 in this Narnia installment, with Susan at 12, Edmund 10, and Lucy 8. Peter is barely into his teens and audiences might expect him to be a bit immature. Instead, Peter is quiet, serious, and protective of everyone else, including Mum. At the London train station, he assures her the siblings will be all right and helps her keep the younger ones organized. He looks with envy at an enlisting soldier, but quickly refocuses on what his siblings need.

Peter “lightens up” once the Pevensies reach Professor Kirke’s home. He gives in to Lucy’s pleas for a game of hide and seek with hardly any prodding and honestly seems to enjoy it. He’s first to suggest a game of cricket when days of rain finally clear up, and provides his own commentary. Yet, the reality that his family is living in wartime and in a stranger’s house with different rules, is never far from Peter’s mind. He’s the first to turn the radio off and keep it off at night when the news reports come in, presumably so said reports won’t scare the younger kids, but perhaps to squelch his own worry. He gets irritated with Edmund, arguably faster and more often than he should. And while he’s gentle when telling Lucy he’s had “enough” of her “imaginings” about Narnia, Peter is firm about her not bringing it up. He implicitly indicates Lucy is lying and being a “little kid” who can’t stop pretending.

Peter understands his sister is little, but fears if she doesn’t face reality, she won’t be able to cope. Lucy could have a breakdown, which would put the Professor in a predicament and worry Mum. But as the Professor hints when speaking to Peter and Susan about Lucy’s “stories,” Peter in particular has let “reality” confuse the truth about Lucy. Namely, of the two younger siblings, Lucy is more truthful and in fact never lies. She’s not showing any clinical mental health symptoms and has no reason to use Narnia maliciously or manipulatively. Thus, the Professor says, “We must assume she’s telling the truth… You’re family. You might just try acting like one.” While we have no evidence of Peter taking this admonition more seriously than Susan, he is the first to apologize when all four siblings end up in Narnia a short time later. He also insists Edmund apologize for his bullying. Thus, Peter takes the lead in deciding how the Pevensies will interact with each other and Narnia from here on. They will act as a family unit, and they will defend Narnia because it’s as real as their home in Finchley.

Yet, Peter’s journey has barely begun. He, Susan, and Lucy find themselves on the run from the White Witch mere hours after their arrival (Edmund has already absconded). When the siblings must cross a deep, icy river, Peter tries to keep his sisters calm and enact a plan. Unfortunately, an argument with Susan over strategy distracts him, and Lucy almost drowns. Peter is so shaken and determined not to mess up again, he lets recklessness take over when he hears a sleigh on the other side of the river. He insists on facing down the Witch alone, stopping only because Mr. Beaver pulls him back and insists, “You’re worth nothing to Narnia dead.”

A Test of Sword and Inner Strength

A subdued Peter completes the journey to Aslan’s camp, seemingly locked onto the “worth nothing” part of Beaver’s statement. Despite the sword and shield Father Christmas gives him, he’s still hesitant to believe he’s worth much to Narnia, his siblings, or perhaps the war-torn England they left. Peter finds just enough confidence to get between Lucy and Susan when a wolf attacks them at Aslan’s camp, but hesitates to “run him through” as Beaver and others encourage. Peter remains frozen with sword drawn as the wolf taunts, “You may think you’re a king, but you’re going to die like a dog!”

As with Lucy and Edmund, Aslan’s presence gives Peter the strength for the next step of his journey. “Stay your weapons. This is Peter’s battle,” Aslan commands his army in a quiet, authoritative voice. The army stands down, and the leering wolf lunges toward Peter and his sisters again. This time, Peter stabs his enemy straight through the heart. The wolf crumples, Lucy and Susan rush forward to hug their brother, and Aslan’s army enjoys a sincere if quiet celebration. Gently, yet firmly, Aslan instructs Peter, “Clean your sword.” Peter obeys and walks away turning over the idea of being not only a king, but a warrior. His stance and body language show his heart no longer quells at the prospect. Still, it will take one more test before our oldest child hero can become the Magnificent king Aslan wants him to be.

A Personal Magnificent Victory

Peter’s final test comes in pre-battle events, particularly his reunion with Edmund. Like his sisters, he forgives Edmund quickly. More important, now he relates to Edmund as a growing man, not a kid he has to babysit. The companionable silence between the brothers during the meal at camp, as well as their banter during training, shows Peter respects what Edmund has endured. However, Peter still worries for Edmund and insists he not endanger himself further. “You are [going home,”] Peter explains in the scene before Aslan’s death. He goes on to imply the girls shouldn’t fight and someone should protect them. Besides, Peter says, Mum would never recover if something happened to the other three kids.

Peter’s plan is a noble one. It speaks to his strengths as an oldest brother, a compassionate and cautious young man, and a person who understood from the outset what real sacrifice should look like. On the other hand, Peter’s desire to protect is somewhat selfish here. That is, he still believes he must fight the battle, literally and figuratively, all by himself. He believes no one else can do what he can and if he’s not in charge and in control, everything will fall apart. In this mindset, the love of family and strength of Aslan mean little to him. He can’t trust them, or if he’s trying, can’t lean on them. When Edmund argues everyone has to stay, himself especially, Peter faces the ultimate battle within himself. Had he sent Edmund and his sisters home, he’d have lost his new, deeper connections with them. He’d have burned himself out and been emotionally defeated even if he bested the White Witch physically. But Peter keeps his siblings by his side, takes the lead in their training, and leads the charge onto the battlefield. When he shouts the famous, “For Narnia!” viewers finally hear the triumphant voice of a young man who fights for the right things with the right motives.

Susan: Smart, Skeptical, and Sanctified

Finally, we come to Susan Pevensie. Her role in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is the smallest of all the Pevensie kids. She doesn’t get one-on-one time with Aslan or a character arc viewers can follow through the movie. If anything, Susan often gets treated like the “throwaway” Pevensie. She’s maligned for being skeptical of Narnia and Aslan as early as LWW and throughout the franchise. Some fans have been so harsh as to call her “condescending” and “a buzz-kill” no matter what rational conclusions she draws or how her actions contribute to the Narnian journey.

As we’ll see later, viewers tend to like her much less in Prince Caspian and Voyage of the Dawn Treader. In fact, she’s barely present in the latter and when she is, comes across as a stereotypical shallow teen. Many readers and viewers, especially Christians, assume that when C.S. Lewis wrote Susan was no longer a friend of Aslan in The Last Battle, he meant her soul faced damnation in hell.

There are plenty of clues in the film franchise, particularly LWW, to prove this interpretation of Susan is wrong. At the very least, it’s misguided. Susan is “needed” in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and in Narnia because the prophecy dictates “two sons of Adam and two daughters of Eve” must sit at Cair Paravel–two kings, two queens. If the equation doesn’t balance, the “evil time” cannot end. Beyond that though, there is much more to Susan and her character arc. She, too, carries her part of the story and has something to teach the first Narnia film’s audience. She too, makes LWW the hit film and modern classic it became. Like her brothers and sister, she does so through being herself, and growing into the “self” Aslan and Narnia have in store for her.

Like Peter, Susan assumes a “caretaker” role to Edmund and Lucy within the first scenes of the film. Although Edmund calls her “Mum” with a bite in his voice, he has a point. From the moment the siblings evacuate, Susan behaves as “little mom” in many situations. She makes sure Edmund goes to bed on time whether he wants to or not. While Peter tries to cheer Lucy up with visions of doing “whatever we want” at Professor Kirke’s manor, Susan ensures she’s tucked in and warm enough. While Peter turns the radio off at night so no one gets nightmares, Susan is more apt to limit their exposure to news during the day, too. Peter sees and completes the assignment in front of him. Susan thinks a step or two ahead.

Peter stays in control because he’s focused on what’s at stake for the whole family. Susan shows a similar bent, but she’s a perfectionist for herself, too. She believes if she missteps, the others may fall, as in a domino effect. That’s why Susan seems just shy of humiliated when Mrs. McCready catches her touching a historical artifact. It’s also why her siblings giggle; because Susan takes herself and rules so seriously, the moment has become much too tense.

Intelligence and Insecurity: A Dangerous Union

If Susan feels the same way, she doesn’t show it. Instead, she leans further into her comfort zone. She uses the strength most viewers and thus contemporary readers, of the Narnia books associate with her–her intellect. Susan, played by Anna Popplewell, is known in TV Tropes as a Brainy Brunette. As a caretaker or “mini-mom,” she is the older sibling most likely to try “educating” the other two, either through education itself (a word origin game), or life skill education (keeping up with their own hygiene and schedules).

Viewers and readers don’t see Susan reading for fun, using big words in everyday sentences, or doing other things a classically smart heroine might do. Yet, Susan is seen reading on the train. She loves words enough to make up her own word game and stick with it when the others are bored. In addition, Susan has a noted interest in Professor Kirke’s artifacts, and she tends to think of the “smartest” answers to problems. When the kids play hide and seek, Susan is the only one who thinks of folding herself into an ottoman–“hiding in plain sight”–rather than rushing to a more “obvious” spot in a separate room. And, cynical or obvious though she might seem, when Susan arrives in Narnia and exclaims, “This is impossible,” viewers understand what she means. Her brain is one step ahead once again. Her “this is impossible” encapsulates deeper questions. “How? Why? What now?” In terms of her siblings, Susan might be asking, “Why us?”

Granted, her natural braininess does get Susan in trouble. Throughout LWW’s second act, she tries to accept Narnia completely, without her natural skepticism. Yet “the real world” constantly intrudes. When the Pevensies meet the talking Mr. Beaver, Susan rolls her eyes and reminds Peter, “He’s a beaver! He shouldn’t be saying anything!” She openly questions Father Christmas’ existence, and then his motives and ability to help the group once he explains Christmas is back on the calendar since Aslan’s return. When Susan gets worried or frightened, as in the river crossing scene, she also falls back on real-world, useless worries. “If Mum knew what we were doing…” she protests, leading Peter to snap, “Mum’s not here!”

Susan’s fear of the unknown, her need for certainty, have made her rationalize and taken her focus from what she needs to do next. Susan is in fact so stuck in her head, the only thought she can grab is, “Let’s just think about this for a minute!” When Peter says they have no time, Susan defends herself, “I’m just trying to be realistic.” Peter counters, “No, you’re trying to be smart, as usual!” He’s correct, but doesn’t communicate well. Susan’s defeated body language, and later loss of temper when Peter can’t keep hold of Lucy, show she feels belittled and ignored. Considering how her siblings have reacted to her other behavior and observations, it’s not a stretch to guess Susan also feels she doesn’t belong in Narnia at all.

The Subtle Reformation of Susan

If Aslan ever knew Susan’s insecurities, talents, or desire for certainty, viewers don’t see it. We do see Susan is as open to Aslan as Peter and Lucy; she reacts to his name “as if a delicious smell…had floated by her.” She pleads with Aslan for Edmund’s life when the other two cannot–“Please, sir, he’s our brother.” Aslan’s death breaks her heart as it did Lucy’s. True to her practical, gentle bent, Susan tries to fight off the mice who swarm the corpse after the fact. But what we know of Susan’s journey otherwise, we are challenged to glean from what we know of Aslan.

For example, we know Aslan is a Christ figure, so we can assume he is omnipotent. Therefore, he would have known ahead of time which Pevensie would betray him, and it was Edmund, not Susan. Leaving aside arguments about predestination, Aslan “chose” Susan to be a queen and follower from the start. It may be Aslan saw Susan as relatable to faithful followers who still had questions or doubts. Aslan may have chosen Susan in the same way Jesus chose the Twelve, who loved Him but would show recorded imperfections (see “Doubting” Thomas, or Peter, who denied Jesus).

We also know Aslan treated each Pevensie as individuals throughout the Narnia series, particularly during LWW. Each one’s journey has something to do with his or her weaknesses and overcoming them through Aslan’s strength, often seen in specific objects or moments. For Susan, one such clue is her gift from Father Christmas. Unlike Lucy, who gets one vial of fire flower juice, or Peter, whose sword and shield must work together, Susan gets two separate gifts. Her bow and arrow are weapons, meaning she’ll have a “traditional” role in the final battle. Her horn, however, is meant to call for help “wherever [she is],” battle or not.

If, as C.S. Lewis implied, Father Christmas works for and with Aslan, Aslan would have influenced these choices. Father Christmas instructs Susan, “Trust in this bow, and it will not easily miss” (emphasis mine). In other words, Susan can trust an arrow will sail if she positions and releases her bow properly because she knows how this weapon physically works. Aslan, through the gift, is asking for a deeper level of trust–the trust that Susan’s faith in Aslan will give her the skill she needs when the stakes are high. As much as she feared she would, trust means Susan won’t fail or fall, nor will her siblings. As for her horn, it reminds Susan to seek and use help, as Peter learned to do. With Susan though, the lesson is a bit different. Notice Father Christmas assures her, “wherever you are, help will come” (emphasis mine).

Unlike Peter, Susan did not try to take the entire family’s load on her shoulders without help. She struggled, again, with fear and uncertainty–when she needed help, would it be there for her? We don’t know much about Susan’s pre-Narnian life, so we could guess “no,” or that Susan got the message she shouldn’t ask for help. Perhaps this is why, as Father Christmas notes, she “[doesn’t] have a problem making [herself] heard.” Perhaps it’s also a part of her journey with Aslan–to learn she is as worthy of help, consideration, and love as her siblings.

Susan’s Sun Finally Rises

Viewers don’t see much of Susan after the Father Christmas scene. However, everything we do see points back to her character development and the learning of truths we have covered, as well as a few others. When Susan tells Lucy, “I’m sorry I’m like that,” after muttering a cynical remark about not getting home, it’s clear she’s seeing how much the war at home has affected her and how much trauma she might be stuffing down. When she touches off a water fight with Lucy in the same scene, viewers laugh with Susan as she finally lets herself relax and enjoy her new fantastical, but real reality. Susan’s willingness to cry with Lucy after Aslan’s death indicates she, the sister who once shut down Lucy’s “imaginings,” now respects emotion-based coping skills. And as noted, it is Aslan’s resurrection that cements Susan’s faith in Narnia, perhaps more than the others’. During that scene, she spends more time than Lucy touching Aslan and marveling at his physical presence, recalling Thomas and the disciples yet again.

Susan is crowned Queen Susan the Gentle, and her direction is “to the radiant southern sun.” More than the others, Susan’s crowning represents the end of her journey in LWW, the beginning of her leadership abilities, and perhaps the success of the film as a whole. Lucy is crowned first, Valiant and “to the glistening eastern sea,” because she was the most valiant and truest believer, and because the east is associated with dawn or new beginnings (Lucy’s discovery of Narnia began everything, and her faith is “white” or “dawn-bright”). Edmund is crowned second, perhaps in deference to his journey being the hardest. He is the Just, “to the great western wood,” because the west is associated with “autumn, twilight, [and letting] go of old beliefs and attitudes,” as Edmund did in a potentially dark “twilight” season. Peter, crowned last as the oldest with the title Magnificent, is given “the clear northern sky,” which can symbolize both the darkness Peter was instrumental in defeating and the North Star. When Aslan gives Peter the northerly designation, he seems to say, “You, Peter the Magnificent, will point Narnia to true north–moral righteousness–and the North Star that is me.”

But while the other three Pevensies’ titles and directions speak to who they were always meant to be, Susan’s is, yes, a bit different. Viewers have little evidence that she has let go of skepticism or anxiety completely, as Edmund let go of gluttony or Lucy let go of being coddled as the youngest child. Susan’s southerly direction speaks to this, too. Esoteric philosophy would associate her with fire, whose ability to burn and destroy often makes it a negative element. The South also has negative Biblical connotations; for instance, south is the direction of “the barren wilderness of Egypt.” If we recall Susan loses her standing as a friend of Narnia later, we might leave her crowning at that, or assume Aslan made a mistake in choosing her as queen.

God, however, makes no mistakes, nor does Aslan as a Christ figure. The South represents “fear of the unknown,” which ties directly back to Susan’s weaknesses. At the same time, Susan’s designation also ties her to summer, the season of the most warmth and light, the season of the day. Aslan then, indirectly tells her, “You are a child of the day; walk and bask in light.” Finally, in calling Susan the “Gentle” queen, Aslan declares Susan’s strength, not her weakness, will be remembered in Narnia. Lucy might be the most loving and emotional, Susan’s title seems to say. Yet Susan, who has been a tireless “mother,” who thought ahead so she could be gentle with others, who sacrificed her natural rationalization in favor of her heart, will be remembered for her mercy.

Aslan’s Story and Ours

By the end of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, the Pevensie children have “remained…for many Narnian years and established the Golden Age of Narnia.” Returning to “the real world” requires they become children again, starting from the exact day they “left” England. Yet the Pevensies never forget their time in Narnia or their time with Aslan. The closing Narnian scenes of the stag hunt indicate the Pevensies have “grown into” the people Aslan knew they could be, physically and otherwise. Even if they can’t keep their physical “grown-up” forms, they are meant to keep the growth of their adventure.

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe works because, like the book on which it is based, the film encourages readers to embrace similar growth. Not every viewer is a Christian, or if they are, many don’t live their Christianity quite the way C.S. Lewis did. In fact, many critics of LWW dislike the film because the Christian allegory is so blatant. Religious beliefs aside though, LWW does remind us we are all part of a much bigger story than we can see. We are not the “main” characters or heroes, but like the Pevensies, we each have personal battles to win. Doing so may help us defeat real-life “villains,” but more likely, our victories will bring us closer to an absolute truth of who we were meant to be and what that means for our lives. No matter how close they were to “the true Aslan,” LWW let every viewer tap into who he or she had been and would become. Every viewer could find a hero or heroine behind those questions, and feel like a real participant in “big stories,” fictional or not.

Prince Caspian: The “Big Story” Shrinks

When Prince Caspian was released in 2008, longtime Narnia fans, newcomers, and everyone in between hoped for a new chapter in Aslan’s epic story. All four Pevensie kids reprised their roles, a big draw for audiences. Released in May as opposed to December, Prince Caspian might have been a spring hit, if not a summer blockbuster. It might have tapped into new levels of enchantment and adventure, showing the young Pevensies actually ruling Narnia and growing even more.

For some fans, Prince Caspian did accomplish these goals. A certain subset of fans love it, rating it more highly than The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe even though that film is still considered the most popular culturally. The fans who prefer Prince Caspian tend to be those who grew up watching the first few Harry Potter films around the time Caspian premiered. They considered LWW “for kids” and didn’t want more “kids’ stuff,” which to varying degrees, fantasy films were (The Thrifty Typewriter). These fans weren’t yet old enough for real adult fare, but were ready to handle realities such as, Prince Caspian is a fantastical war story. Thus, real people, not just fantastical creatures, will be casualties. Additionally, “more mature” and “darker” themes will be explored, such as what it means to rule a kingdom, form one’s own belief system, or deal with the implications of events like war.

A film that promised such explorations, packaged in the more mature yet comforting Narnian landscape, did draw that subset of fans back to theaters. It also attracted new fans, perhaps especially older kids and adults who found the first installment charming, but a little too heavy-handed in its whimsy and obvious in its symbolism. (One Rotten Tomatoes critic who hated LWW wrote, “Aslan = Jesus. Now you don’t have to buy a ticket”). Unfortunately, the expectations of a Narnia that could “grow with” its audience similar to the way Hogwarts does, were not met.

In reality, Prince Caspian had good “bone structure,” as it were. Unfortunately, real-world budgeting conflicts, a lackluster release month, and poor box office numbers meant the second film didn’t have nearly the impact on audiences as its predecessor. Worse, Prince Caspian revealed a terrible misunderstanding of C.S. Lewis’ original book, the messages he meant to convey with it, and how to translate those messages from book to screen. The two mediums clashed and audiences struggled to find their footing within the story. Aslan’s “big story” of hope, redemption, and restoration shrank. The Narnia that remained left little if any room for audiences to identify with the Pevensies or any other characters as they did with The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

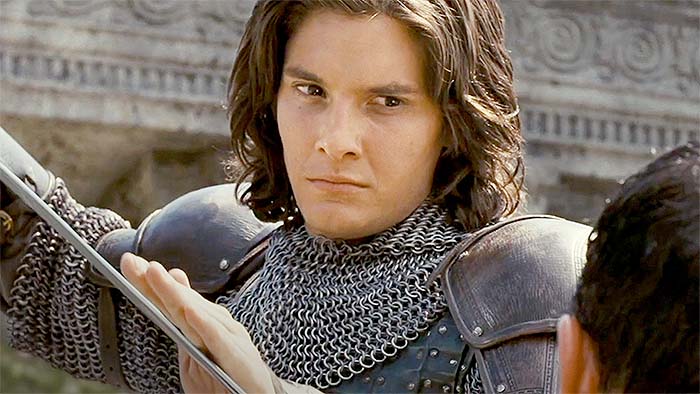

Prince Caspian Himself: A “Chosen One” With an Unclear Mission

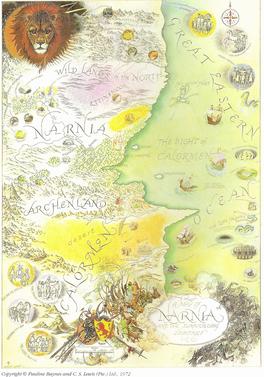

Prince Caspian‘s first and biggest mistake was and is its focus on the eponymous protagonist. Played by Ben Barnes, the young prince has a familiar but compelling backstory. He was born a Telmarine, or a citizen of the Island of Telmar, which is in the country of Calormen, “a semi-arid empire south of Narnia.” The Telmarines originally invaded Narnia and enslaved many Narnians, including and especially the country’s talking animals. However, Aslan named Caspian the true heir to the throne of Narnia after the Pevensies’ Golden Age, because Caspian was “a son of Adam” who embraced Aslan’s values, including self-sacrifice for others. Apparently, Caspian embraced Aslan’s worldview after growing up on stories his Narnian nursemaid told him after the death of his parents. Caspian concealed his beliefs because his aunt and uncle, particularly his evil Uncle Miraz, believed the Narnian stories were nothing more than useless “fairy tales.”

Caspian, then, is a familiar character–an orphan with a somewhat mysterious, noble, and often royal destiny, whose cruel relations keep him from claiming his rightful place in the world. Familiar and trope-heavy though his story is, Caspian remains the kind of character audiences love rooting for. He is an underdog who will have to fight for his throne. The enemy he will fight is his own uncle, and blood ties, plus the uncle’s iron grip on Narnia, complicate matters. Additionally, Caspian is a “secret heir” with a secret of his own. He’s unable to lean into Narnian beliefs and the strength of Aslan as much as he wants or needs to. Like the Pevensies, he’s faced with the choice to serve Aslan and fulfill the calling that entails. Since that calling involves a throne, Caspian’s journey is familiar and fits what audiences expect of Aslan’s “big story.” In other words, not every Narnian citizen, or real person, is a royal. But fulfilling any destiny can be summed up as taking a kind of “throne.”

However, Caspian’s character and mission get muddled early on in the film. The beginning lacks focus; viewers are yanked from the Pevensies’ unexpected journey to a completely changed Narnia, to the scene of Caspian’s birth decades prior. They’re then yanked to new locales and expected to understand new problems over and over again. One moment, the Pevensies are piecing together what happened to their beloved country after the Golden Age. The next, they are trying to discern the motives of a dwarf named Trumpkin, a former slave who excoriates them for leaving Narnia in the lurch for 1000 years, but claims the siblings are urgently needed. Yet, viewers can’t invest in these developments because a couple scenes later, they’re enmeshed in Telmarine/Narnian relations and the consequences of Miraz’ reign, which include constant, unjust executions.

Clumsily woven into all this, viewers must deal with Caspian’s external and internal angst. He has some idea that he’s the rightful heir to the Narnian throne. Still, he’s unclear on the implications, how he will defeat Miraz, or if he should try. The film truncates or eliminates some important information, such as the role of Dr. Cornelius, Caspian’s tutor who has schooled him in the Old Narnian ways and prepared him to take the throne for years. Therefore, although the tutor appears onscreen, he’s more a random character who spirits Caspian away when Miraz threatens to kill him. Viewers and Caspian are left fairly confused about what Miraz’ plans are, why they required Caspian’s murder, and how Dr. Cornelius fits in. The next time viewers can truly focus on Caspian, he’s raising an army in the Narnian forest, with the Pevensies’ help.

The Pevensies: Satellites in Their Own Story

The Pevensies’ reappearance, and the supposed renewed focus on them, is a relief. Here at last are the characters The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe’s audience fell in love with, grew with, and rooted for. They’re a year older, and earlier scenes have hinted at more complex problems they may face in this Narnian journey. Better, their interaction with Narnian citizens provide at least some of the context Prince Caspian, the film and character, have left out so far. Reepicheep, Nikabrik, and other Old Narnians explain the Pevensies have found their way to Aslan’s How and are expected to fight in his army again.

Prince Caspian also adds a new prophecy, a story element with which fans are familiar. Just as the Pevensies became Narnian royalty through prophecy, Caspian the Tenth has one of his own. The Narnian prophet Glenstrom explains Aslan’s choice of Caspian as heir. As the Beavers did in LWW, he goes on to say now is the exact time for Caspian to step forward and fight for his throne. This context lets viewers find their footing again.

Additionally, the reappearance of the Pevensies at this juncture helps viewers understand why their earlier appearances mattered, before the focus shifted to Caspian. Unlike with the original book, director Andrew Adamson took time to linger on the emotional upheaval the Pevensies have faced in the year since leaving Narnia and becoming children again. Peter can’t let go of being High King and in charge. Edmund has slipped back into surliness and channeled it into fights with classmates, attacking one boy before they’re even on the train to school. Lucy’s older siblings treat her like any faith in Narnia is silly and childish again, while Susan has thrown herself into her studies, but struggles socially.

These relapses are understandable, and viewers follow the Pevensies because they’re eager to see how the trauma will resolve now that their favorite characters are older and wiser. An alliance between the Pevensie siblings and Caspian would be a good setup for a gritty, action-packed, yet fairytale-esque resolution for all parties. Said alliance would feed back into the bigger story of Aslan, Narnia, and the Christian journey C.S. Lewis sought to represent.

None of this happens. The Pevensies are not just secondary to Caspian, as might be natural. Instead, they become satellites. They rarely work as a unit, as they did in LWW. They’re often seen as truncated duos or trios, and those are often at odds with each other. What viewers get are interludes of the Pevensies wherein they stay “stuck” in a relapsed state or their characters arguably deteriorate. Peter, for instance, leads a reckless charge on Miraz’ castle and gets half of Caspian’s army killed. Lucy’s faith in Aslan remains unwavering, but she stands alone in it for a good chunk of the film. It reads as if all three of the others have forgotten everything they learned from Aslan, or that he and Narnia existed at all. Meanwhile, Edmund and Peter spend much of the film’s middle arguing about who will take charge and who Peter is truly fighting for. Susan remains dedicated to Narnia, but Adamson and the film’s pacing seem more interested in the crush she develops on Caspian.

Constant Action, Little Purpose

Granted, the Pevensies and other characters don’t get much chance to develop. Prince Caspian mainly focuses on several battle scenes, each over ten minutes long. In fairness, the battles between Caspian and Miraz’ armies are key parts of the original book, too. The difference is, books are an almost complete opposite medium from film. Therefore, C.S. Lewis spent more “page time” on Caspian’s development of faith in Aslan, his accompanying doubts, and any personal goals tied to ousting Miraz and assuming kingship.

In contrast, the film moves almost from one battle to another with little character or spiritual development. The most viewers get is the revelation that Miraz killed Caspian’s father, for which the son wants revenge. In contrast to the book, where Caspian knew this from the beginning, the revelation is placed well into the three-hour film. Both the placement, its brevity, and Caspian’s explosive anger feel odd. Once again, Caspian feels like a two-dimensional, wooden protagonist.

The Pevensies don’t fare much better. Only Peter and Lucy get real character development. As with Caspian, what they receive is short and almost negligible when compared to the exhaustive battle scenes. Their arcs are also told rather than shown. As noted, Edmund and Susan outright ask Peter who he’s really fighting for. Later, Peter admits he was focused more on himself than Narnia. It reaches the point that Susan, not Peter, not the High King, gives the famous “For Narnia” battle cry during the climax. Peter may as well have come out and said, “I learned how to stop being self-absorbed” or “I learned being High King means not being in charge all the time.” Firstly, had he learned this more organically, as in LWW, it would’ve had a bigger impact. Secondly, Peter’s arc looks quite similar to the one in the first film, wherein the pressures of being in charge eroded his confidence.

Lucy’s arc isn’t as preachy but is rather on the nose. When she is on screen, it’s mostly alone. Prince Caspian uses her physical isolation to emphasize Lucy is the only one clinging to faith in Aslan. At first, she’s vocal about that faith. Early in the film though, Peter tells her, “We’ve waited for Aslan long enough,” in the same tone he used to tell her to stop talking about Narnia in the first film. Lucy retreats into her former shell, choosing not to follow Aslan even though she can see him. Later on, Aslan comes to her while she’s alone again in the forest. They embrace, and Lucy rejoices at seeing him. “You seem bigger,” she says, and Aslan agrees, “Every time you see me, I will seem bigger.” Gently but firmly, he scolds Lucy for not following him earlier. Lucy apologizes, admitting she became afraid of what the others would think. “Dear one,” Aslan chuckles, “if you were any braver, you would be a lioness.”

Aslan’s encouragement heartens Lucy. Her journey is also easier for the audience to follow. In Prince Caspian, Lucy reads less innocent and saintly and more like a real child for whom C.S. Lewis wrote his books. Even a child who has already professed faith can relate better to this Lucy, because his or her faith is also still growing and changing. As Aslan puts it, though Peter and Susan have “learned all they can from [Narnia]” by Prince Caspian‘s end, Edmund and Lucy are still acquiring Narnian skills.

However, Lucy’s arc isn’t enough to bring Prince Caspian out of its two-dimensional state. As with Peter’s, this time, her arc is not shown through her actions or symbols like “the glistening eastern sea.” Rather, it is told, fed to the viewers. Some of this is forgivable because Lucy is the youngest character and a surrogate for young viewers. But her temporary loss of faith in Aslan isn’t truly something she has to work through. It doesn’t affect her in any meaningful way. She seems more like a kid blowing off a minor peer pressure incident than a young queen dealing with the implications of helping her realm. The fact that she can easily accept the explanation of Aslan not saving everyone immediately, and can still lean on Caspian and her older siblings to do much of the battle’s “work,” further dilutes her effectiveness.

Mixed Genre and Forced Elements

Finally, Prince Caspian is considered the “box office bomb” of the Narnian film trilogy because not only did it streamline the original book, it echoed so many of the book’s flaws. As noted above, one such flaw lies in the execution of Lewis’ faith-based messages. A child-friendly, but deep, coming-of-age story in which youths “grow into” their worldviews became a preachy morality tale covered up with battles to keep the attention spans of audiences fifty years younger than the original. However, Prince Caspian had many smaller issues that, taken together, became a much larger, thornier one.

This thorny issue comes down to an unfocused genre. Where The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe focused on Narnia’s whimsy and the epic struggle between good and evil, Prince Caspian knew these were covered. The Pevensie children had already become kings and queens; they had already become adults in Narnia; there was nowhere to “go from there,” as Clarendon House Publishing puts it. Clarendon House goes on to theorize that while writing Prince Caspian, “Lewis had lost patience with his own idea,” and was reacting out of “pressure” to reuse the same protagonists and same Narnian locales. Since the Pevensies cannot return to ignorance of Narnia, they end up piecing together clues to find out who Caspian is and what he needs from them. The tale becomes a weird, vaguely Medieval detective story.

The film tries to bring back Narnia’s fantasy element with an army of talking animals and fantasy species, including a warrior mouse named Reepicheep and a dwarf named Trumpkin. This works somewhat, some of the time. Trumpkin gets some brief dialogue wherein he explains hardships under Miraz made him abandon belief in Aslan. Reepicheep’s faith is contrasted with the unbelief of a badger named Nikabrik, who is eager to use black magic to win the war. But Trumpkin’s “faith crisis” is hardly touched on, and as for the black magic element, it too is barely present. Plus, when Aslan does aid in the final battle, he summons a river god or spirit as an ally, which further confuses the faith issues. The “detective story” viewers began with eventually turns into a mishmash of war movie, mythological epic, and morality tale with just enough whimsy for it to be “Narnian in name only,” so to speak.

Aslan’s Story Nearly Disappears

This “mixed genre” problem indicates severe lack of vision in Prince Caspian‘s director and writers. It seems they noticed Lewis’ original problem, that the novel felt “forced.” Perhaps they were simply working with what they had and, like Lewis, felt pressure to please audiences. At the same time, there were ways in which the team behind Prince Caspian could’ve kept itself grounded in Narnia as a fantastical world in which a multi-part fantasy story was being played out. Streamlining the 150-minute length, eliminating some action scenes, or giving fewer characters more to do may have helped. As it was, the franchise would need a huge improvement if it hoped to maintain loyalty.

The Voyage of the Dawn Treader: A Trip “Home” Run Aground

Sixteen years after its release, Prince Caspian has some fans. That said, the movie made only $418 million worldwide, an abysmal total compared to The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe’s $745 million. By 2010, the Narnian film franchise was all but forgotten. Any talk of more films coming out had been reduced to whispers. Thus, when The Voyage of the Dawn Treader hit theaters on December 10, 2010, all but the most enthusiastic fans ignored it. Even the enthusiasts admitted skepticism, largely because Prince Caspian had not met their expectations.

Initially, Dawn Treader looked like it might break Prince Caspian‘s curse. It had much more going for it. Like its successful predecessor, Dawn Treader had a December release. Film-goers would attend screenings in a holiday mood. As with LWW, the holiday release date would capitalize on whimsy and nostalgia, whereas Prince Caspian‘s mid-spring release date had no particular feelings or connotations attached. And like LWW, Dawn Treader appeared more grounded in fantasy. Posters and trailers prominently featured the title ship with its golden dragon figurehead and royal purple sails, which Lucy describes as, “such a very Narnian ship.” They also featured a backlit Aslan, who appeared nowhere in Prince Caspian‘s materials, and a snowfall.

Additionally, the Pevensies were back for this third film, but only Edmund and Lucy. Additionally, a new child character, Eustace, would have a main role. Although Eustace was a brat, he would receive significant character development. These changes, plus a new director, Michael Apted, a new writing team, and a new partnership between Walden Media and Fox, poised Dawn Treader to breathe life back into the franchise. The changes would also push the new film back into “family” territory, rather than seeming too much like an action or mystery story.

As was somewhat expected after Prince Caspian flopped, Dawn Treader did hit some “sandbars” with fans. Older fans point out the seafaring aspect was a huge one; they allege Dawn Treader was trying too hard to keep up with, or become an incarnation of, the burgeoning hit series Pirates of the Caribbean (The Thrifty Typewriter). Typewriter and other fans also dislike Dawn Treader’s focus on completely new characters such as Eustace, especially when taken with the film’s attempt to keep the Pevensies relevant. Since those children are much older now, these fans allege, they seem shoehorned into Dawn Treader because they are familiar.

Fans can no longer connect with the Pevensies because, well, half of them aren’t relevant to the plot, except when Edmund and Lucy negatively compare themselves to Peter and Susan. As for Narnia itself, it’s technically not even part of the story, and the way in which the characters access it–almost drowning after being sucked into a painting–feels forced. Thrifty Typewriter calls it “by far the worst way” to access Narnia in the entire trilogy.

Purely from a storytelling standpoint, Dawn Treader is more a mixed bag than Prince Caspian, and we cannot neglect its successes. However, its poor box office totals, $4 million less than its predecessor, and its other negatives, mean those successes were too small. Dawn Treader was the original Narnia trilogy’s death blow. If Narnia is to resurrect, we must find out why, while keeping anything of worth we find among the flotsam and jetsam.

Successes: A Return “Home” to Aslan’s Story

The small, significant successes in Voyage of the Dawn Treader all point back to a return to Aslan’s “big story” as seen in LWW. Dawn Treader‘s version is not as whimsical as LWW. Nor is it as immersive as the overarching stories in Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter, the latter of which was wrapping up its film franchise in 2010 with great audience fanfare. However, the character arcs, settings, and themes of Dawn Treader capture the spirit of Lewis’ Narnia more than Prince Caspian did. They spark interest in what could have come next for the existing film series and leave room for current directors and writers to explore what remains untouched in the Narnian landscape.

First Success: The Presence of Eustace

“There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.” C.S. Lewis opened the original book thus, hooking his readers with the introduction of a new character and an unlikeable lead, at that. Readers or viewers follow unlikeable leads because they do the unexpected. They are not heroic; they are rarely if ever going to do the right thing unless they can manipulate that choice. Thus, consumers want to know how leads like Eustace, of all people, will succeed in a story. Furthermore, writing Eustace “almost” deserves his unfortunate name reveals some good exists in this boy. He is young and malleable. He has a spark of nobility, even if finding it will take work. In fact, working to find what is good about Eustace Scrubb will be part of the fun for new consumers.

Eustace, played by Will Poulter, does not disappoint. According to Lewis’ Narnian timeline, Eustace is 9 years old, while Will Poulter was 17 during filming. But despite being twice the “recommended” age, Poulter did an admirable job playing a much younger, snobbish spoiled brat. Eustace’s journal entries and demeanor show he’s smart for his age, but immature. He’s whiny, tattling to his father that Edmund intends to hit him when Edmund never laid a finger on him. He threatens to “tell Mother” when the painting of the Dawn Treader sucks himself, Edmund, and Lucy into Narnia, and carries on screaming and ranting about being kidnapped when he lands on deck. In the original book, Lewis describes Eustace crying “harder than any boy his age has a right to cry when nothing worse than a wetting has happened to him.” Overall, Eustace comes across as coddled, not nurtured, loved, but not disciplined.

Eustace is the perfect foil to Edmund and Lucy. He calls them childish and unstable for believing in Narnia, but their belief in Narnia adds to the Pevensies’ maturity. Aboard the Dawn Treader, Lucy and Edmund are greeted by royal title, but settle in as ordinary Narnian citizens. They accept the grittiness of shipboard conditions while Eustace continues whining, demanding, and applying “real world” logic to Narnia in arrogant ways (“I’ll contact the embassy! This is a kidnapping!”) Where Eustace’s cousins join in the humor and companionship of the crew, Eustace holds himself separate. And while anyone unfamiliar with Narnia would be shocked to find animals or humanoids like centaurs exist, Eustace takes shock and disbelief to the level of Fantastic Racism (applying fantastical slurs and racist or eugenicist attitudes to fictional and/or non-human species).

Note then, that Eustace is unlike any human child or teen who’s featured in Narnia films so far. He’s the furthest thing from loving, faithful Lucy, and smart though he is, he doesn’t have Susan’s wisdom. His cowardice proves him the polar opposite of Peter. Viewers can’t sympathize with him as they learned to do with Edmund, because unlike Edmund, Eustace hasn’t had to fight for an identity among siblings. He’s never been challenged to protect anyone and failed in that duty, as Edmund did with Lucy. Eustace is the last child Aslan should choose to carry on the Narnian legacy, but proves himself perfect for the role the worse he gets.

The Intricacies of Eustace’s Arc

To their credit, the Dawn Treader crew is mostly undaunted at Eustace’s actions. Prince Caspian jokes about “[throwing] him back,” but wouldn’t seriously harm a fellow royal’s relative. Warrior mouse Reepicheep in particular is downright honorable toward Eustace, once he gets over the other’s uncouth handling of his tail. Reepicheep continually offers Eustace advice on coping with life aboard the Dawn Treader. He also tricks Eustace into uncomfortable situations, such as crossing swords with him. Reepicheep may be much smaller and non-human, but the former’s experience and maturity mean Eustace is bested and humbled.

The more Eustace rejects and mocks the warrior mouse, the more tenacious Reepicheep becomes in trying to show the boy who he really is–and who he could become. The rest of the crew participates in smaller ways, such as letting Eustace fall on his face when he refuses their help disembarking, or laughing at his bluster when the boy doesn’t appreciate the crew rescued him from an enemy slave market.

But Eustace must face the ugly truth about himself before he’s ready to play a heroic role in the final Narnia film. In an abandoned cave, Eustace finds a treasure trove and is immediately entranced. He falls on it, eager to take the entire thing, and finds himself transformed into a dragon. Aslan isn’t present, but it’s heavily implied he transformed Eustace through Narnian magic. Eustace is left unable to communicate, moving slowly and clumsily. He’s furious, but also disoriented and terrified. Eustace tries to reunite with Caspian, Edmund, Lucy, and the others, but is mistaken for a random dragon on a rampage.

Eustace maintains human intelligence, writing I AM EUSTACE in volcanic soil using fire. The Dawn Treader crew is wise enough to welcome him back, if not completely forgive him right away. For his part, Eustace still has a warped sense of self to work through. Unfortunately, the film leaves out much of his introspection, although in fairness, Eustace can’t speak or journal for much of the middle. However, viewers do see Reepicheep “nursing” Eustace through a “recovery” period. The mouse comforts his new dragon charge, singing him an old lullaby and telling him stories. Later on, he gives Eustace a pep talk–“You breathe fire, mate! You’ve got a body that could destroy this whole island!” This, plus reminders of Eustace’s other innate gifts, set our former antagonist on the path to accepting the hero he could become. Eventually, he opens up enough to be vulnerable and cry a single tear in front of Reepicheep, who treats the display as honorable.

Eustace is changed back into a boy shortly before the climactic battle. Again, the film glosses over the “how.” All viewers see is that Eustace separates from the group again. This time around though, they are his compatriots, and he is seeking a way to help them circumvent an evil green Mist that has been seducing and tempting everyone, leading to emotional disaster. An exhausted Eustace is changed back during a brief sleep, and returns to report Aslan did it for him. “It hurt a little bit,” he admits, “but it’s the good kind of hurt.”

Eustace doesn’t reveal anything else about his encounter with Aslan, but he does echo some earlier truths about the Great Lion, such as, “He’s not safe, but he’s good.” Eustace’s journey builds on truths the Pevensies have learned, such as, sometimes following Aslan and growing in faith hurts. However, Aslan never harms a true follower. “The good kind of hurt” is more from facing or doing hard things, expanding one’s wisdom or limits.

Second Success: The Pevensies’ Final Lessons

Lucy and Edmund experience “the good kind of hurt” along with Eustace. As faithful followers of Aslan, their final lessons in Narnia focus more on temptations and the choices they’ll face as they transition back into the “real world” permanently. Yet, it is important they learn these lessons in Narnia alongside Eustace so they can retain their foundational knowledge of good and evil. As Aslan explains, it’s part of why they were brought to Narnia at all.

Lucy’s True Value

Lucy encounters her “last temptation” first, before the main trio enters Narnia. As the younger Pevensie with the strongest faith, she has coped better overall with their aunt, uncle, the insufferable Eustace, and the fact that Peter and Susan get to go to America with Mom and Dad. Still, Lucy is now old enough to understand the implications of being left behind. She’s old enough to worry about the deprivations of WWII, and she’s chafing against both circumstances. This manifests as envy of and desire to imitate Susan. In early scenes, Lucy asks Edmund if he thinks she’s as beautiful as Susan, and copies what she thinks are Susan’s successful flirtatious gestures. Once aboard the Dawn Treader, she’s happy to be back in Narnia, but thoughts of Susan distract her. At the first opportunity, viewers see Lucy in her cabin, staring in the mirror. It’s a sharp departure from the more thoughtful and intuitive queen of the other films.

Lucy doesn’t get much focus in Dawn Treader; Michael Apted makes it look as though her desire to look like Susan is all she cares about. But viewers who have read the original book, or who recall the “real” Lucy, will note a deeper struggle. Lucy is growing up, but not fast enough. She wants to be older, admired, and mature. She wants young men to desire her, but beyond that, she wants attention–a different kind than she’s always had as the youngest child. Lucy sees Susan as physically and socially perfect, and she wants that perfection.

In the original novel, Lucy encounters a spell book she must use to “make what is unseen, seen,” and steals it when she discovers a spell that would make her just like Susan. But Lucy gets more than she bargained for when she becomes Susan, forfeiting her own existence and her family’s knowledge of Narnia. The film streamlines this, having Lucy take the spell book back to her cabin (meaning it was aboard ship, so she technically never stole it) and simply read the spell before dreaming of becoming Susan. The film also adds a moment of hesitation before Lucy takes the book. She reacts as Aslan calls, “Lucy!” and then jump back as his roar fans the pages. But Lucy ultimately does dream Narnia did not exist for her family, and that she never existed either. Shaken, she wakes calling for help.

This time, it’s not Susan who appears in Lucy’s mirror but Aslan. “I wanted to be like Susan,” Lucy explains with tears in her voice when Aslan asks why she read the spell. “You doubt your value,” Aslan agrees. He adds, “Don’t run from who you really are.” Lucy doesn’t verbalize understanding, but like many one-on-one encounters with Aslan, the silence between them, body language, and orchestrations communicate a pivotal moment. The next time viewers see Lucy, she is dedicated to the present moment, fighting alongside Caspian and Edmund, and speaking up to remind the other two where they should be focused when the battle threatens to deteriorate into a shouting match. It’s hinted she’s ready to step into a mentor role for younger kids as well.

Aslan’s words to Lucy are “on the nose” for some viewers. Her conflict might irritate viewers who remember “the problem of Susan,” who was “no longer a friend of Narnia” at the end of the book series. Many readers and viewers worry Susan was thrown into hell because she dared show interest in clothes and lipstick. But just as “the problem of Susan” is deeper than it seems, so is Lucy’s “last temptation” and final Narnian lesson. Note the spell Lucy uses to become “like” Susan. It actually reads, “make me she whom I’d agree/holds more beauty over me.”

Lucy doesn’t want beauty or attention for their own sake. She feels Susan, as the older sister, has always had the control in their relationship. Susan has always been prettier, smarter, trusted more, and given more responsibility. She is “more,” Lucy is “less,” and Lucy has reached the point of the dynamic controlling her, being held over her. In using a spell, something that can break, Lucy literally seeks to break Susan’s hold on her and become her own woman, even if she’s not a woman yet. It’s a deeper and perhaps less self-focused desire than it seems on the surface.

Secondly, note how Lucy’s final lesson echoes who she was when the series began and who she became for her siblings. “Your family wouldn’t know Narnia without you,” Aslan reminds her. Viewers could infer Lucy can’t “become” Susan because without her, there is no story. They would be right, but again, Lucy’s “last temptation” goes deeper. Aslan never forbids her from choosing Susan’s path; it’s implied Aslan gives Lucy free will as Christ gives it to humans. Also, note Aslan does not leave Lucy trapped in her vision of non-existence as punishment. He restores her the moment she calls out, and explains the consequences of her choice. Therefore, Lucy’s last temptation comes down to accepting who she is–strengths and weaknesses alike–or choosing what she sees as perfection in the real world, while giving up Narnia and the faith that has made her the woman she will become.

Choosing the real world’s “perfection” doesn’t mean she would “go to hell” or that no one would ever find Narnia, including her siblings. But it would mean Lucy would have lost the best part of herself. That’s why having Aslan speak to her in such plain language is successful. Lucy has doubted her value and forgotten who and what her “best part” is. Only someone who loves and values her as deeply and simply as Aslan does, can help her recover it.

Edmund’s Spiritual Battle

As for Edmund’s “last temptation,” it doesn’t happen until everyone is aboard the Dawn Treader. There are hints in England, such as Edmund’s resentment of sharing a room with Eustace while Lucy gets her own, and his constant clashes with Eustace. As viewers discover though, these have a deeper root than frustration or envy. Aslan’s sacrifice has kept Edmund firmly rooted in his identity as King Edmund the Just, no matter which world he’s in. However, viewers soon learn Edmund is falling back into some old patterns as he grows up and learns to translate Narnian skills to “the real world.”

Right after boarding the Dawn Treader, Edmund asks Caspian why he and Lucy have been summoned. Caspian hopes the Pevensies can help him find the Seven Great Lords of Narnia. Caspian’s Uncle Miraz had banished them from Narnia years ago. Their true fates are not known, though it’s rumored Miraz may have had one or more murdered. Caspian had sworn a coronation oath to find and restore the Lords if he could, sailing “a year and a day” to do so and leaving Trumpkin the dwarf as a trusted regent in the meantime. Edmund takes charge, offering plans for the best way to reach the Lone Islands. However, he’s quickly corrected–it’s Caspian’s ship, and he is in command on this journey.

Edmund masks his frustration, but stews as he once did when Peter was given a higher leadership role. Some of his true feelings leak out during the film, such as when a sword-fighting lesson with Caspian “accidentally” goes too far. Edmund tends to butt in front of Caspian physically or verbally once the group begins searching for the seven Great Lords. As befits his still-pugnacious nature, he shows anger at Eustace that, while justified, only encourages the latter’s negative behavior. Additionally, Edmund tries to protect Lucy, but Caspian often gets there first, if Lucy isn’t defending herself. Both situations, Edmund increasingly resents.

About midway through Dawn Treader, viewers find Edmund’s behavior has a deeper source. Like Lucy, who wasn’t just jealous of Susan, Edmund isn’t just jealous of Caspian or fearful of losing his role as Lucy’s big brother. Edmund has been having nightmares of the White Witch, and unlike Lucy’s dream of Susan, his recur. In Edmund’s nightmares, the Witch manifests as a sickly green, misty apparition. She seduces him–“Come, Edmund darling. Come with me. Be my king.” Her words echo the empty promises from LWW. Now that Edmund’s older, they carry a hint of sensual propositioning, though C.S. Lewis likely wouldn’t have had a villain in a children’s story explore such.

Edmund and the others discover the Witch isn’t real, in that she’s not physically present. But she is a threat wrapped up in the physical one they must defeat. She has become part of The Mist, a green ether that materializes when its victims think of their greatest fears. Once The Mist appears, it can suck away victims for good. It’s said entire ships have been lost to it, especially around the nearby Dark Island, a place where those stranded there must relive their worst nightmares. It’s implied at least one missing Lord met his death because of The Mist.

Edmund’s last temptation becomes the embodiment of his final and most vital Narnian lesson, his best opportunity to step into kingship. The Mist reveals a fear he’s kept hidden for years. Despite Aslan’s redemption, the White Witch could somehow “take over,” and Edmund could revert to the pre-Narnian boy he was. Edmund’s insecurities echo those of a Christian who has hurt others or faced trauma and fears reliving the past. Some Christians call facing such fears undertaking “spiritual warfare.” This can involve everything from prayer and Scripture reading or memorization to fasting or anointings. For someone like Edmund, it often involves faith-based counseling.

Facing Spiritual and Fleshly Adversaries

Edmund doesn’t have a Bible or anointing oil in Narnia. Narnians don’t “pray to” Aslan as Christians pray to Jesus. Hinting to Lucy and Caspian that he’s having trouble does help a bit. However, it’s not until the climax on Dark Island that Edmund faces the whole truth about his spiritual battle–it has a fleshly component.

Dark Island brings out the weak, negative, fleshly side of everyone on the crew. By this point, they’ve fought through a slave market (at which a trader almost bought Caspian and Lucy), recovered Eustace, and fought a sea serpent, among other travails. The entire crew is beyond spent and uninclined to endure the quirks that would usually just get on each other’s nerves. So when the group faces a real dragon and has to strategize, and Caspian jumps into “leader” position too fast for Edmund’s taste–again–the latter can’t take it anymore.

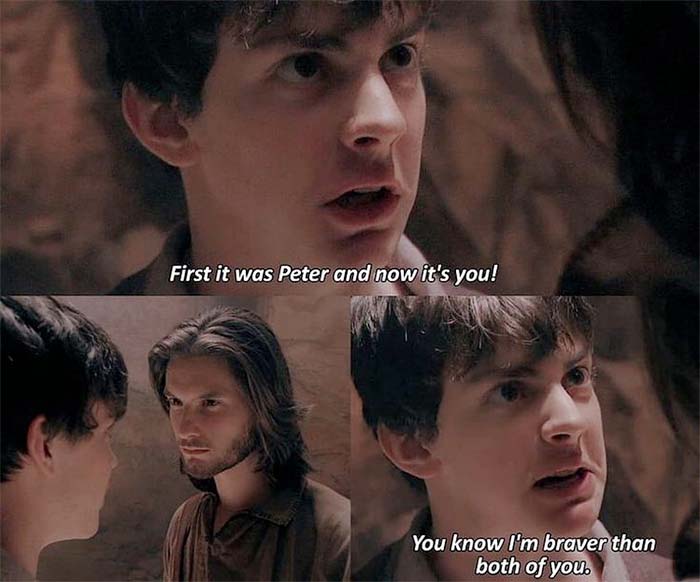

“I’m sick of playing number two!” Edmund bursts out. “First it was Peter, now you! I’m a king! I deserve to be a king! I deserve my own kingdom!” Edmund’s bottled anger spills onto the deck like so much bilge. The greed, anger, and lust for power he thought he’d overcome still exists, worse now than four years ago. Back then, a boy who said such things could be written off as a kid whining and moaning, like Eustace. Edmund though, is now a young man. A young man filled with such anger and grasping would be dangerous if given a kingdom, even if his emotions were understandable. That young man couldn’t rule subjects effectively because he would be ruling out of unresolved conflict and damaged self-worth.