The Evolution of “No Longer Human”

Since its 1948 publication, Dazai Osamu’s No Longer Human (「人間失格」, Ningen Shikkaku, lit. “Disqualified as Human”) has skyrocketed in popularity: becoming the second best-selling novel in Japanese history with Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro taking top honors. Through this popularity, Dazai’s modern classic has been integrated into contemporary pop culture by means of new media such as manga, film, and anime. While characters in manga such as Nozomu Itoshiki, the protagonist of Sayonara, Zetsubou-Sensei (2005), are based on No Longer Human‘s protagonist, there have also been three separate manga adaptations of the work itself. Only one remake published by Gakken in 2011 as part of a classical literature series stays true to the original novel—the two others divert into postwar settings designed by Usamaru Furuya or use obscure symbolism specific to Yasunori Ninose’s work. No Longer Human was adapted to film by director Genjiro Arato in 2009, the hundredth anniversary of Dazai’s birth, and a four-episode anime version of the novel was developed by studio Madhouse, also in 2009. This anime is a part of the award-winning series Aoi Bungaku (lit. “Blue Literature”) which adapts traditional works of Japanese literature such as No Longer Human and Kokoro into anime format. Of these numerous variations on the original work, Aoi Bungaku poses the richest retelling.

Since its 1948 publication, Dazai Osamu’s No Longer Human (「人間失格」, Ningen Shikkaku, lit. “Disqualified as Human”) has skyrocketed in popularity: becoming the second best-selling novel in Japanese history with Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro taking top honors. Through this popularity, Dazai’s modern classic has been integrated into contemporary pop culture by means of new media such as manga, film, and anime. While characters in manga such as Nozomu Itoshiki, the protagonist of Sayonara, Zetsubou-Sensei (2005), are based on No Longer Human‘s protagonist, there have also been three separate manga adaptations of the work itself. Only one remake published by Gakken in 2011 as part of a classical literature series stays true to the original novel—the two others divert into postwar settings designed by Usamaru Furuya or use obscure symbolism specific to Yasunori Ninose’s work. No Longer Human was adapted to film by director Genjiro Arato in 2009, the hundredth anniversary of Dazai’s birth, and a four-episode anime version of the novel was developed by studio Madhouse, also in 2009. This anime is a part of the award-winning series Aoi Bungaku (lit. “Blue Literature”) which adapts traditional works of Japanese literature such as No Longer Human and Kokoro into anime format. Of these numerous variations on the original work, Aoi Bungaku poses the richest retelling.

To preface the discussion of the anime version of the work, Dazai Osamu’s original 1948 novel must be examined. No Longer Human follows the life of traumatized Oba Yozo who is wholly unable to reveal his true self to others. While later in the novel Yozo numbs himself through taking on countless sexual partners, drowning in alcoholism, and succumbing to morphine addiction; his initial reaction to the frivolousness of human interaction is to play the clown and project a persona that altogether upholds a feeling of hollow joviality. This buffoonery begins for Yozo as a vain way to gain interpersonal relationships without emotional depth due to the abuse he suffered from a female servant in his youth. His antics go so far as to prevent him from intervening in the later sexual assault on his wife by a casual acquaintance and set him on a course of rapidly declining health. The general assumption behind this piece is that it represents Dazai Osamu’s life during World War II through the his signature dark comedic lens; moreover, the story is shaped as a pained retrospective by heavily featuring the past-passive voice and semi-rational frame narratives.

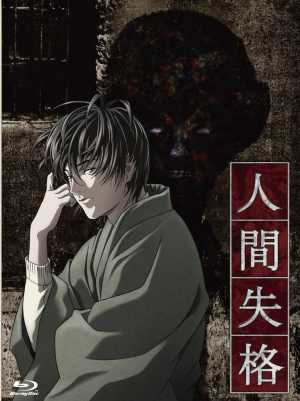

Although Aoi Bungaku maintains the characters, setting, and overarching story of the Dazai’s original, many liberties in plot construction are taken by Madhouse in developing the adaptation. A very noticeable change is that the structure of the whole story is not a retrospective or reflection; rather, it is told through the present view of Oba Yozo. The core story still follows the same path of a young man with intense feelings of alienation towards society and the feeling of humanity but begins with Yozo meeting Tsuneko, the first victim of his double suicide attempts, in Tokyo rather than with his childhood in Northeastern Japan. Yozo’s childhood is now recounted using flashbacks throughout the series to give supporting evidence for mental breaks as they happen. From here, the main story arc continues, while perfectly sequencing events as they come, through to the end when the madam of the bar in Kyobashi that Yozo frequented concludes and frames the story while speaking to a reporter just as in the novel:

“‘It’s his father’s fault,’ she said unemotionally. ‘The Yozo we knew was so easy-going and amusing, and if only he hadn’t drunk—no, even though he did drink—he was a good boy, an angel'” (Dazai 177).

Another major change comes in the portrayal of Yozo. While in No Longer Human Yozo is portrayed as cold and pitiable as a result of his past trauma from the female servants of his childhood home and his father’s reign over him, in Aoi Bungaku Yozo is shown as a desperate, paranoid young man grasping at straws. Yozo’s descent into madness is also highly characterized in Aoi Bungaku by the spirits and guilt that haunt him. The viewer is bombarded with terrorizing images of Tsuneko’s death scene, the mask Yozo’s father forced upon him as a child, and the distorted drawings of Yozo’s inhuman “true self”. Herein lies Madhouse’s true strength of the anime medium as they personify Yozo’s hyper-depressive feelings of inadequacy in society as a pseudo-physical being that follows Yozo around and tortures his psyche with the fact that he will never qualify as human—that he is, in fact, this grotesque, ghastly monster. The abolition of the inflicted passive voice for an active storyline is rectified by means of this sadomasochistic imp.

From this, the final change is revealed: that Aoi Bungaku is a contemporary, visual piece that pulls from No Longer Human without being bound by the origin medium’s limitations. Without exclusive knowledge of Japanese literature, foreigners have had little to no reason to investigate the classic writings of prominent figures such as Dazai Osamu or Natsume Soseki. These novelists of the early twentieth century centered their stories on the lives and struggles of Japanese people—what could be called a brand of esoteric fiction.

In modern times, the taste of the foreign consumer of Japanese-brand products has shifted greatly from spiritualist movements and classical written works to the technologically advanced culture for which Japan has come to be known. While Japanese authors such as Murakami Haruki (Norwegian Wood (1987), Kafka on the Shore (2002), 1Q84 (2009-2010)) continue to penetrate Western shores with their engaging, global-natured novels, the most basic consumer pays little to no mind to these works—instead turning his or her attention towards visual pieces that hold a perceived sense of instant gratification. I say “perceived” because, as explored previously, the entire depth of Dazai Osamu’s original novel is retold faithfully in the anime medium despite being a four episode series rather than a 177-page novel. Time is constrained but depth of content is not. Madhouse does not sacrifice details for its modern audience; rather, the studio adapts existing ideas to the new structure.

As such, by utilizing this shift in audience desires, Aoi Bungaku transcends the bounds that made No Longer Human a purely Japanese piece and give the story the chance to be recognized in pop culture outside of Japan. Moreover, it is truly genius for Madhouse—a favorite studio of Western audiences for anime series and movies such as Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust (2000), Paranoia Agent (2004), Death Note (2006), Paprika (2006) and Black Lagoon (2006)—to use their signature style as a vehicle to communicate these classic pieces of literature.

In addition, William Tsutsui explains in his book Japanese Popular Culture and Globalization that the popular creativity of Japan holds foreign audiences eager to learn more about the culture—even through piracy of fan-translated, non-localized products.

“With a missionary zeal for turning on international audiences to the Japanese pop forms they love, fervent fan communities are an often overlooked element in the global spread of Japanese culture” (Tsutsui 46).

I believe through methods such as these, Madhouse believed they could reach the Western audiences who had grown familiar with their material and would openly accept Aoi Bungaku as a new meaningful site of identification and aspiration in the contemporary global imagination.

This new proliferation of official anime publications reflects the extent to which the anime graphics and narrative style have been recognized as a familiar and accessible vehicle of communication. There is perhaps no other culture in which the “cartoon” has so successfully permeated popular contemporary cultural practices as the anime medium in Japan and around the world. An article titled “Can Anime Boost Japan?” was published in the North American Post on April 25, 2012 regarding the soft power and cultural influence Japan truly holds. The author of the article, Genya Ozeki, states,

“A survey carried by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs shows the number of Japanese enthusiasts motivated by anime has been increasing.”

Following this, in an interview with Benjamin Erickson, Cultural and Educational Program Director at the Hyogo Business and Cultural Center, Erickson states,

“Anime and manga can […] give rise to interests in Japanese traditional culture. Subculture can play an important role as a gateway to various Japanese cultures.”

While it is true that anime series such as Aoi Bungaku could lead viewers to read more traditional Japanese literature, this practice of investigating further may not be entirely necessary. Enlightening as it is to consume all versions of a given story, when a contemporary adaptation fully encapsulates everything that the original work presented, subsequently pushes the work into an entirely different realm of popular culture, and opens it up to an influx of new readings and interpretations; the possibility exists that the most current adaptation is investigation enough. Passing on culture to and adapting it for a modern audience is not a new concept, but it is not often that we can present anime as a source of higher learning and inconceivable depth.

Works Cited

Buckley, Sandra. Encyclopedia of Contemporary Japanese Culture. London: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Dazai, Osamu. No Longer Human. Norfolk, CN: New Directions, 1958. Print.

Ozeki, Genya. “Can Anime Boost Japan?” North American Post [Seattle, WA] 24 Apr. 2012, 1st ed., sec. 4. Electronic Resource.

Suzuki, Satoshi. “Ningen Shikkaku.” Aoi Bungaku. Dir. Morio Asaka. Prod. Madhouse. NTV. 11 Oct. 2009. Television.

Tsutsui, William. Japanese Popular Culture and Globalization. Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Asian Studies, 2010. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Personally, I think novel mirrored Albert Camus’s “The Fall” in the way that it explores the relationship between a private “I” and a social “me”.

Definitely! Dazai would have reveled in the Camus’ existentialist writings– had he lived to read them, that is.

One hell of a read!

The anime was was too short to properly develop any character, particularly judging by how complex some stories were. So, the characters were left stranded due to the over-focus on the execution of the whole series.

While I agree that the anime did not bring light to every little tangential nook and cranny the novel had to offer, it instead focused more on just the anti-hero. This gave a certain clarity to the audience that Madhouse was trying to reach.

Art is just amazing, best ive ever seen in anime!

It’s been years since I read this, I remember it as a great substantial exploration of what humans are. Which I did not sell my copy back when.

Very nice article. I am a writer as well and my future article on post-humanism may will greatly benefit from this and the book.

This is indeed a valuable book in post-war Japan, when many people were lost. I’d say the only thing more depressing than the author’s stories is his biography.

Between Dazai and Akutagawa’s biographies, I don’t know which is more depressing.

Solid study! A real surprise of a book. It went past all my ideas about Eastern societies and the place of individuality during the period it was written. I was terrified and attracted to the character throughout and knowing the outward opinion of Yozo given in the interview of the madame at the end makes me want to know him more. I was depressed yet enthralled.

Apart from being a fan of anime in generael, I am also (and to a much bigger degree) a huge fan of asian literature. When I heard that there was an anime based on classical Japanese literature, I nearly fell off my seat.

Studied Psychology so I’m still fascinated with it so it is given that my most favourite genre is psychological based stories. One of my greatest fascinations would also be episodic type of stories. And so with this anime that brings those two together is already a sure jackpot for me.

I’ve read some Haruki. This makes me want to read Osamu. Good review. Where did you learn review writing???

I have yet to explore East Asian literature, this might be an interesting introduction.

Aoi Bungaku is a masterpiece.

One of the novels I read for school that I enjoyed a lot. It is so interesting how Osamu Dazai noted out how we are all influenced by everyone we interact with directly and indirectly. Quite depressing, but I found the story very intriguing.

Fantastic article! I’m definitely going to check out Aoi Bungaku again–maybe even check out some of Osamu’s novels for summer reading 🙂

That was a fascinating article! Having never read the original novel,this illuminates a lot of Aoi Bungaku’s version. I now appreciate an anime I had previously discarded. Thanks.

An amazing article! This makes me want to watch Aoi Bungaku.