Persona: A Journey through the Shadow in Ingmar Bergman’s Masterpiece

No form of art goes beyond ordinary consciousness as film does, straight to our emotions, deep into the dark room of the soul.

―Ingmar Bergman

In Ingmar Bergman’s prolific career, Persona (1966) is arguably his most recognizable yet puzzling masterpiece.

It was 1965. Bergman was admitted to Sophiahemmet, the royal hospital in Sweden, for illnesses due to overwork. He nonetheless decided to keep his hands busy while convalescing. The hospitalization placed Bergman in a different world, segregating him from the hustle of several demanding roles. The hospital stay, while disabling the auteur, enabled him to reflect upon and question the nature of his works. This was when Bergman conceived the idea for Persona. The director claimed that he “went as far as he could go” for the film, and by doing so, the film “saved his life.” Some argued that this refers to Bergman’s artistry, but it would not be an exaggeration if one thinks of Bergman’s actual life, for his life depended on artistic creations.

This life-saving film chronicles the story of a stage actress Elisabet Vogler 1 falling silent in the middle of a performance of the Greek tragedy Electra, subsequently being taken to a mental hospital and placed under the care of nurse Alma. Following Doctor Lindkvist’s advice, the two of them move to a remote island in hopes of a speedier recovery for Elisabet.

Persona―Theatrical Mask

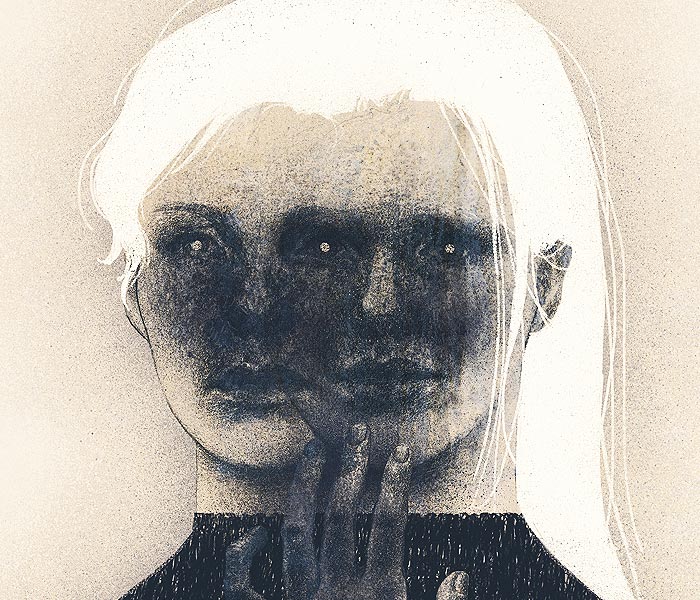

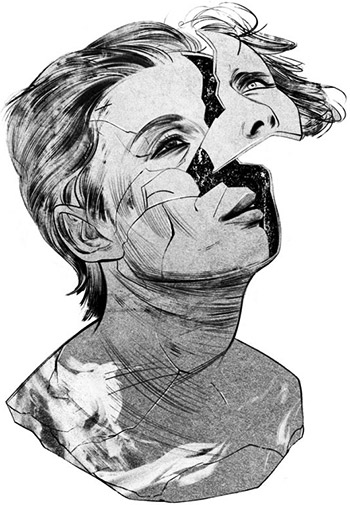

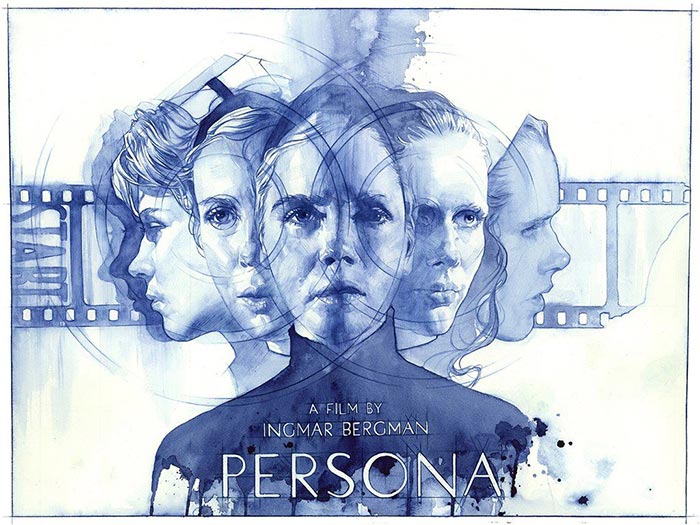

Among all film critics, Jacques Mandelbaum’s descriptions perhaps best fit the theme of the discussion below: the film is about “the reversible nature of appearances, the porosity of faces and absolute deprivation.” 2 The theatrical promotional posters of Persona, which advertised with the close-up shots of the lead actresses, confirm the importance of human face in the film. Human faces demonstrate the psychic processes of a human being, and in this connection, it brings us back to the title of the film, Persona. The word persona originated from Latin, meaning a “theatrical mask.” Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung developed and defined the concept persona as “the individual’s system of adaptation to, or the manner he assumes in dealing with, the world.” 3 In simpler words, “it is a kind of mask, designed on one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and on the other to conceal the true nature of the individual.” To Jung, the persona was not just individual, it was social, historical, interpersonal and collective. As a social construction, it does not only conceal the flaws of an individual to the world, but also possibly to the individuals themselves. On the other hand, the recognition of a person’s shortcomings and powerlessness necessarily requires the individual’s acknowledgement of the multiplicity of roles they play in their lives.

Naturally, any individual would wish to keep such grim part of themselves hidden from the world, but Bergman chose to use cinematography to expose this side of human beings on the silver screen. In fact, the film was originally titled Cinematography, only to be abandoned and took on the title Persona at the advice of a film company executive. Bergman wrote in his book Images: My Life in Film that, in Persona, he “touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover.” He recognized how important cinematography was to him, for it “transcended the words I [he] lacked, the music which I [he] could not master, and paintings which left me [him] cold.” In fact, the power of cinema lies in that, as a medium, it allows people to live through an experience, thus to understand the indescribable.

Through taking the audience on a journey through the shadow, Bergman unfolded the Jungian individuation process in front of the audience’s eyes. Jung’s individuation process works as self-healing mechanism by recognizing and accepting the darker qualities of an individual. Jungian shadow refers to the “aspect of our personality that does not relate to our cultural notion of ‘goodness’.” Bergman expert Hubert Cohen noted that through Elisabet’s role, Bergman portrayed “the worst side of his [Bergman’s] own personality” and by the worst side of one’s personality, we can infer it as the person’s shadow. Every light casts a shadow, so wherever goodness goes, wretchedness follows. And according to Bibi Andersson, who played Nurse Alma in the film and a frequent collaborator of Bergman, whenever Bergman wrote a film script, he wrote it according to the personality of the actor/actress he wanted to be cast for the role. She also revealed that, at the time Bergman asked her to play Alma, which, according to her, is a character full of insecurities, the actress herself struggled with her own insecurities. If we are to decipher what Bergman expressed through the film, one could easily come to the conclusion that the film showcased an exposure of the shadow, the dark side of human beings.

According to Jung, people who are fixated in one particular persona hinder their psychological growth. Therefore, in the film, both Elisabet and Alma undergo the process of recognizing and accepting each other’s shadows. Any explorations of the shadow benefits the psyche as it provides meanings, feelings and possibility of finding values in life, an aspect that shall not be overlooked. In addition, bringing up the shadow eradicates its looming destructive power. Letting the shadow take the lead creates the possibility of leading the psyche onto the road of health.

The Journey Begins

In Persona, such exploration of the dark side of humanity starts off with the filming process, with film rolling and filming equipment turning on. This scene echoes with the ending scene, in which the audience will again see the same filming process. Such matching works function as a hint to show that this film is about the filming of a film, that the audience is about to witness an artificial construction (i.e.: a film is built on elaborate acts and performances, hence falsehood). Soon after this scene we see an approximately five-minute long montage of seemingly unrelated images. They, however, all represent motifs to be seen again later in the film: an erected penis, signifying a functioning patriarchy; the killing of a lamb, connoting the sacrifice of lamb from the Bible; hammering of a nail through a human hand, a reminiscence of crucifixion of Jesus and the prior betrayal from Judas; a short clip of a silent comedy taken from a scene in Bergman’s 1949 film Prison, in which a man preparing for sleep is startled by a burglar, Death, a vampire and a police officer, ended with Death chasing the three humans off the windows; a spider, a reference to the reincarnation of an omniscient divinity Anansi, followed by a picture of pointed steel fence, implying segregation and prohibition of trespassing.

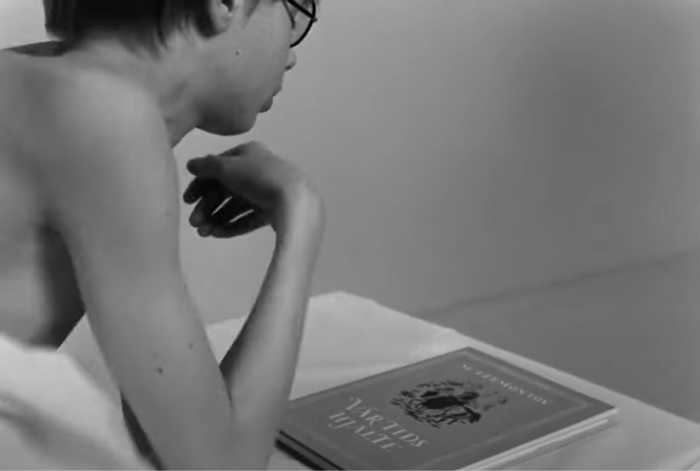

After the five-minute long montage, the scene changes to a morgue-like space. A shirtless boy lying on a bed wakes up, puts on his glasses, then reads the book placed next to him which is titled A Hero of Our Time. In Bergman’s 1963 film The Silence¸ the same child actor is also seen reading the same book 4. It is believed to be Mikhail Lermontov’s work, which tells the story of a talented man who cannot fit into social norms. If Bergman’s use of this book in Persona is any hint to the audience for what follows in the film, it would not be difficult to deduce his message: you are about to witness the journey of a cowardly hero, someone who is not as good as s/he would like to be.

The Individual

Segregation from the outside world begins at the beginning of the film, when the psychiatrist assigns Elisabet to nurse Alma in a mental hospital. Elisabet is then seen in her vast hospital room, equipped with nothing but a bed, a radio and a television. The radio and television shows are the only intrusions from the outside world in the all-encompassing room. In a sense, Elisabet’s hospitalization equates a solitary imprisonment. For Elisabet, however, as she shuts herself in and refuses to talk, it appears that she finds such a stay preferable.

Several scenes from Bergman’s final film before retirement, the 4-hour long Bildungsroman Fanny and Alexander (1982), can be borrowed for analysis here in Persona. In Fanny and Alexander, after being rescued from the attic lockup for disobedience in his abusive stepfather Bishop Edvard’s home to his protective Uncle Isak’s home, the nephew of protagonist Alexander’s uncle, Aron, brings breakfast with Alexander to his androgynous brother Ismael, who is incarcerated in the family home’s dungeon for being a threat to others for possessing extraordinary abilities. Ismael shows Alexander why he is being considered dangerous. By asking Alexander to put down his name (Alexander Ekdahl) on a piece of paper and read what is now written on it (Ismael Retzinsky), Ismael demonstrates how the two of them are actually “the same.” He says to Alexander,

Perhaps we’re the same person, with no boundaries. Perhaps we flow through each other, stream through each other boundlessly and magnificently.

This scene shares much similarity with a scene near the end of Persona and can be borrowed to understand its meaning. Alma confronts Elisabet about her indifference toward her son’s massive and unfathomable love for her. The sequence was shot from two perspectives: one showing the mute Elisabet with a narration from Alma, the other showing the narrating Alma and the back of Elisabet’s head. In both sequences, half of the actresses’ face are shrouded in their shadows.

The heated confrontation uncovers Elisabet’s unspeakable secrets. Alma’s abilities to analyze Elisabet’s treatment of her role as a mother akin to telepathy, an all-knowing ability similar to that of Ismael, who can read Alexander’s mind. As soon as Alma finishes her monologue, Elisabet and Alma’s faces are merged into one. Earlier in the film, Alma comments that she thinks she looks like Elisabet, only that Elisabet is more beautiful. “I think I could change myself into you if I tried” said Alma. Elisabet and Alma thus can be seen as the “same person,” who can exchange their roles and perform duties just like the other person.

What happens next in Alexander’s encounter with Ismael in Fanny and Alexander further proves this point. In the sequence, Ismael tells Alexander, “You bear such terrible thoughts. It’s almost painful to be near you.” He then narrates a scene in Alexander’s mind in which Bishop Edvard is slowly being burned to death by a fire started by the bishop’s ancient, bedridden aunt. When Alexander asks Ismael to stop talking about what is on his mind, Ismael replies it was not him talking; he is simply speaking Alexander’s mind.

Similarly, in Persona, Alma reveal the dark secret of Elisabet to her, to which Elisabet responds by turning away from Alma and remaining silent,

You wanted to be a mother. When you knew it was definite, you became afraid, afraid of responsibility, afraid of being tied down, afraid to leave the theater, afraid of pain, afraid of dying, afraid of your swelling body.….When you knew it was inevitable, you started to hate the child and wished it would be stillborn. You wished that the baby would be dead….You looked with disgust at your screaming child and whispered, “Can’t you die soon? Can’t you die?”

This scene’s significance lies in the fact that Alma exposes Elisabet’s shortcoming and secret―mother is the one role that Elisabet is unable to play. Elisabet feels shameful for her inability, which is why she falls silent when performing Electra, for her realization of her own hatred for her mother, as well as her tearing up of her son’s photo. Bergman, in his autobiography The Magic Lantern, noted that, to him, cinema is “a powerfully erotic business” for “the mutual exposure is total.” As a result, following the mutual exposure―of Alma recounting a beach orgy resulted in an unwanted pregnancy, and Alma revealing Elisabet’s lack of motherliness, the mute patient slowly becomes more responsive.

After the heated one-way confrontation between Alma and Elisabet above, Alma gashes her wrist and forces Elisabet to drink her blood. This could be read as psychic vampirism – Elisabet feeding off Alma’s life force. But when viewing this scene together with the kiss shared between Aron and Ismael as Aron leaves Alexander alone with Ismael, Elisabet is not necessarily taking energy away from Alma; rather, Elisabet and Alma, and Aron and Ismael are merely exchanging a part of themselves with each other. If Aron in Fanny and Alexander, who can roam free in the house and thus enjoys a higher degree of freedom than Ismael, exchanges a part of himself with Ismael, who is being confined in a small room, Aron also exchanges a part of his freedom with his brother’s confinement. Aron bringing breakfast to Ismael with Alexander and subsequently breaking the rules by allowing Ismael to talk to Alexander alone serves as a good example of this exchange of freedom. Alma’s remark to Elisabet at the end, “I’ve learned a lot” can testify that the two of them exchange deep, unspoken knowledge about each other.

Again, Elisabet is a human being with an extraordinary understanding of the falsehood of human acts, while Ismael also possesses a super-human-like ability in understanding human beings’ thoughts. These human “vampires” do not actively inflict harm on others as they do not enervate; and what they do is to make the other person (Alma and Alexander) realize their own shadows. Unlike the unwilling victims of vampires, Alma and Alexander willingly go to Elisabet and Ismael and allow them to have power over them. The exchange of secrets thus foster understanding and growth.

If we compare Elisabet at the beginning of the film with Elisabet in this blood-sucking scene, her change is noticeable: the audience are witnessing the changing of roles between Elisabet and Alma. Elisabet’s unwilling, sudden utterance when Alma threatens to throw a bowl of boiling water at her is an immediate threat of death, which effectively initiated a starting point of verbal responsiveness (albeit forced) for her. And when she later drinks blood from Alma, that signifies another step forward for Elisabet, for her shredding of her silent role and her beginning of re-acceptance of her roles as a mother, an actress, and a wife.

At the end of Persona, a man is then seen facing the audience, filming with a camera, with the filming equipment slowly turning off. As mentioned above, this ending scene and the opening montage suggest that we could be in fact watching the making of a film. We can confirm that nothing, whether it is reality or illusion, is ever really certain, for no definitive explanation is given for the relationship between the opening and ending scenes with the rest of the film. Are we watching a film, or are we watching a film within a film, or are we audience part of the film (because the filming camera is facing us)? On the topic of illusion and reality, Jung reckoned “what we are pleased to call illusion may be for the psyche an extremely important life-factor” i.e.: reality and illusion are simply equally important. Even if we can distinguish reality from illusion, it can just be a misleading discovery, a futile endeavor. It is unlikely that Bergman agreed that dreams, thoughts and the shame that entailed from them shall be oppressed.

In the denouement of Persona, Alma tidies up the cottage house and prepares to leave. As she exits the house, a giant stone head sculpture with a sad expression facing the sky is stood in front of the house, occupying more than half of the camera frame – again, Bergman is known for shooting close-ups of human faces. We can almost interpret that this stone sculpture, one made of a formation of thousands of years, is telling us what we just saw in the film, this human tragedy, the porosity of façade, had been there since the beginning of time. And as Alma leaves the house with camera slowly turning off, it is suggested that Elisabet also recovers from her muteness and return to normalcy.

History

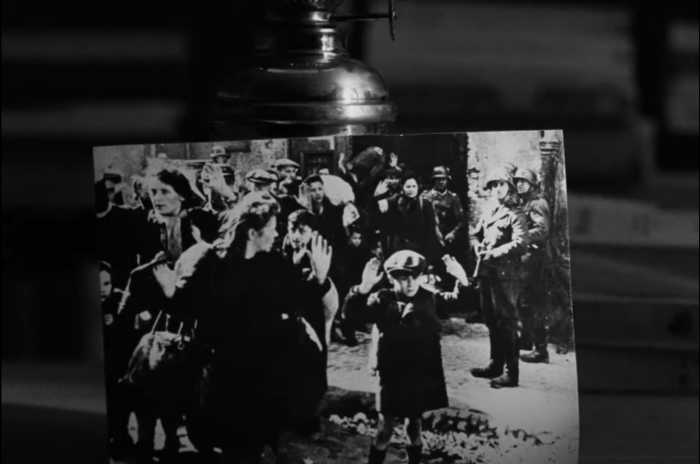

Earlier in Persona, Elisabet is seen pacing around her hospital room while the television shows a clip believed to be the self-immolation by Vietnamese monk Thích Quảng Đức in 1963 in protest of the government’s persecution of Buddhist monks, to which Elisabet recoils in a horrified facial expression. Elisabet will face similar human atrocities again: by her bedside, she stares at a photo of a Jewish boy raising his arms as a gesture of surrender in Warsaw Ghetto during the Second World War. Some argue that any mentions of real-world affairs in Bergman’s films were an oddity, for Bergman was once called “an artist in an ivory tower in an isolated country.” Bergman would continue to receive similar criticisms later, such as alleging him for not shedding lights on social issues with his new-found fame. The director in fact admitted that he could not grasp human catastrophes like the Holocaust. Nevertheless, the Vietnamese monk self-immolation and the iconic Warsaw Ghetto boy picture disprove the idea that Bergman was a secluded artist making his films in the ivory tower, for in Persona, Elisabet’s contemplative expression can explain not only Bergman’s own shadow, but also the nature of photos.

In the second time Elisabet witnesses a great human cruelty, she does not respond with a horrified expression like the first time; instead, she contemplates and stares long into the photo. This scene in Persona very subtly implies the unreliability of photo as evidence, and no one can be certain about the story that taken place in the photo. We can even take one step further and infer that a widely-recognized human catastrophe, like the Nazi’s Holocaust, can yield different interpretations other than being a one-sided devilish act perpetuated by the media and mainstream history course books.

In Bergman’s youth, he was fascinated by Nazism. While most European filmmakers from Bergman’s generation leans far left, Bergman went to the opposite and ran for the far right. He only “crushed with shame and guilt” for his Nazi admiration in 1946, when the war was over. In his interview with Jörn Donner in 1977, Bergman remarked that when he found out about the concentration camps during the Nazi’s reign, he felt like he “had discovered that God and the Devil are two sides of the same coin.” 5 As Walter Benjamin famously remarked, “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism” 6 and historical materialist ought to “brush history against the grain” i.e.: to view history from the perspective of the defeated, the aspect of Nazism that gained Bergman’s admiration is possibly not as grim as the media perpetuates 7, hence the photo showing the little boy with his arms up in the air might carry a different side to the existing, well-known story.

Social Order

As mentioned above, imprisonment does not only appear as a motif in Persona, it also appears in Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander. Alexander and his sister Fanny’s disobedience brought them punishments―being locked up in the attic by their stepfather Bishop Edvard. Ismael is also imprisoned on the lowest level of the house, for his possession of the exceptional ability to understand human beings. Alexander’s Uncle Isak, much like Ismael, appears to be in possession of magical power as well, who is even more “powerful” than Bishop Edvard. Disobedience, superior intelligence as well as Elisabet’s “great mental strength” in maintaining voluntary silence, all deemed as undesirable in patriarchy and shall be punished, repressed, and removed from the visible by all means.

Back to the questionable kiss shared between Aron and Ismael: in this scene, the brothers do not only exchange a part of themselves with each other, or like what Elisabet and Alma turn out to be at the end of the film, they also blur a distinction: social hierarchy. Alma in the scene in which she lets Elisabet drink her blood is related to vampirism. This scene is analogous to the blood-drinking scene of Elisabet and Alma: Alma is supposed to be the caretaker of Elisabet, but she breaks the order by allowing Elisabet to drink her blood. In a traditional setting, if Elisabet is a vampire, this would turn Alma into a vampire, changing her from the caregiver role to a role of peer.

At the beginning of the film, before Elisabet and Alma moves to the doctor’s summer cottage house, Doctor Lindkvist gives her monologue about her “diagnosis” on Elisabet:

But you can refuse to move, refuse to talk, so that you don’t have to lie. You can shut yourself in. Then you needn’t play any parts or make wrong gestures. Or so you thought….I understand why you don’t speak, why you don’t move, why you’ve created a part for yourself out of apathy. I understand. I admire. You should go on with this part until it is played out, until it loses interest for you. Then you can leave it, just as you’ve left your other parts one by one.

Understanding Elisabet’s situation requires the doctor putting herself into Elisabet’s shoes and her own recognition of role-playing, meaning the doctor is just as “mad” as Elisabet. A smoking doctor also does not command authority; rather, it proves that even the doctor herself is a character playing in the film/in real life. As for Nurse Alma, she breaks her role by deliberately leaving a shard of broken glass on the ground and let the unwitting Elisabet walks on it. When her first attempt to elicit a verbal response from Elisabet fails, she goes as far as threatening to pour a pot of boiling water to Elisabet. Although Elisabet gives in by yelling, “No! Don’t do it!” Alma’s act significantly undermines her role as a nurse and as a caretaker. If Dr. Lindkvist, nurse Alma and patient Elisabet are all performing their roles within a structure we called society, none of the hierarchical strata exist, resulting in dissolution of hierarchy. 8

As members of a society, we all act out our roles. Our assigned roles require us to perform accordingly, so that our society runs in order. The world in Persona is a secluded one, which is the opposite of our functioning society. Even though “[e]very inflection and every gesture a lie, every smile a grimace” and every light casts a shadow, as Jung argued, and we cannot live as recluses as Bergman himself did after retirement, and hierarchy, as a social construction, is not preferable, what we should do in this world, and how should we navigate this falsehood, how do we deal with the porosity of life? As we cannot be Elisabet, the only way forward, is to try to accept the unavoidable wretchedness of our roles, to perform as best as we can, on every stage of life.

Works Cited

- This is the second time the surname Vogler appeared in Bergman’s films. In Bergman’s 1958 film The Magician (Swedish: Ansiktet, meaning “The Face”), actor Max von Sydow, whom Bergman called his “first and best Stradivarius,” played the lead character, a magician named Albert Vogler. Actress Liv Ullmann, who plays Elisabet in Persona, recalled in documentary Liv and Ingmar (2012) that Bergman also used to call her “his Stradivarius.” Both Voglers in The Magician and Persona are stage performers. Also in The Magician, Albert Vogler pretends to be mute when an officer tries to expose his frauds. More on the names of Bergman’s film characters: http://www.ingmarbergman.se/en/universe/egerman-vogler-co ↩

- Mandelbaum, Jacques. Masters of Cinema: Ingmar Bergman. Phaidon Press, 2008. ↩

- Jung, Carl G.. Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Princeton UP, 2014. ↩

- Bergman used to call The Silence and Persona “a sonata for two voices.” The director also remarked that the two female leads of The Silence, Ester and Anna, are different parts of the same psyche. ↩

- Interestingly, what came closest to a criticism from Jung toward the Nazi was that the “pagan god of storm and frenzy” caused the Nazi military actions. He also considered Nazism possessed “positive potential” despite the brutality. ↩

- Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Schocken Books, 1969. ↩

- It is worth noting that Napoleon and Alexander the Great both caused great casualty in their conquests, but they were being hailed as giants in history because of their victories in the battlefield. ↩

- Baumlin, James S., et al. Post-Jungian Criticism. SUNY Press, 2004.

Bergman, Ingmar. Images: My Life in Film. Translated by Marianne Ruuth, Faber and Faber, 1995.

—. The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. Translated by Joan Tate, Hamish Hamilton Ltd, 1988.

—, director. Fanny and Alexander. Sandrew Film & Teater. 1982.

—, director. Persona. AB Svensk Filmindustri, 1966.

—, director. Prison. Terrafilm, 1949.

—, director, The Silence. Svensk Filmindustri, 1963.

Gado, Frank. The Passion of Ingmar Bergman. Duke UP, 1986.

Koskinen, Maaret. Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence: Pictures in the Typewriter, Writings on theScreen. Washington UP, 2010.

Long, Robert Emmet. Ingmar Bergman: Film and Stage. Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1994.

Ohlin, Peter. “Bergman’s Nazi Past.” Scandinavian Studies, vol. 81, no. 4, 2009, pp. 437–474. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40920877.

—. “The Holocaust in Ingmar Bergman’s ‘Persona’: The Instability of Imagery.” Scandinavian Studies, vol. 77, no. 2, 2005, pp. 241–274. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40920587.

Rowland, Susan. Jung: A Feminist Revision. Polity, 2002.

Sarris, Andrew. Confession of a Cultist. Simon & Schuster, 1971. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

For a while back, I stayed a week at Ingmar Bergman’s biggest cabin on a beautiful island in Sweden named Fårö. I am a writer and director (outside of my work here at The Artifice) so every year, a few creatives are invited to stay at his inspiring spaces. I went there to flesh out our feature film project and it was profoundly productive.

Super atmospheric. Every space in the cabin was decorated in a way for you to get inspired to write. It was also really interesting to go through his private film collection. A lot of surprises there.

One of the most interesting things was how he wrote ideas all over his house – on everything. For example, next to his bed, you can see random writing sketched on a wooden table.

Anyway, a small trivia for you which you didn’t ask for!

Thanks for sharing this with us! Visiting Fårö is definitely on my bucket list. I wish that I could live like Bergman by the time I retire too.

Pairs well with Mulholland Drive.

Because lesbians? That’s where the similarities more or less end.

Because the psychological and identity related themes, references to cinema. They’ve a little more in common than the sexual orientation of the leads, not the least of which is Lynch citing Persona as an influence.

Mulholland Drive is a great film but it does feel almost like a horror film at times. Its better than Eraserhead.

I like Lynch but Persona runs rings around MD.

Bergman was an extraordinary director and Persona was one of his many masterpieces.

Persona is a film that had a profound impact on how I looked at other films, and art in many other mediums for that matter.

Yes, an excellent analysis of an excellent film. I gave this my ‘folded arms’ test: when I watch a supposed classic for the first time with an attitude of: “Okay, impress me then…”. And it did. It’s one of those films that punches even harder than you expect.

I have the same habit. I really want to see this film.

I’m not a Bergman connoisseur and he’s probably the auteur I know the least. Seventh Seal is the only one I’ve seen. But now I want to watch Persona. Thank you.

The Seventh Seal is very different from Persona. And if you like Persona, check out The Silence (1963) too!

For what it’s worth I’ve only seen a handful of Bergmans, perhaps 6-7 of the better known ones, and none of the others seem anything like The Seventh Seal to me. In fact it’s a film I’ve always pretty much hated, while liking/loving most of the others. Persona wouldn’t be a bad place to start, Cries and Whispers, Sommarlek and Winter Light are all also fantastic.

Liv Ullman is such a wonferful actor. There is a scene in Autumn Sonata where she sits beside her mother on the piano bench and watches her play Chopin- right after playing a clumsy version of the same piece to her- and she watches her fingers with some envy but then her eyes come up to look at her face and you just see all this mixed emotion of awe for her talent, longing for her love and sadness. Gives me a shiver everytime.

My favourite Bergman film. Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light come very, very close to this, though.

Mine too – although The Silence runs it close. In truth, though, Bergman’s whole, varied career contains discretely brilliant phases, from early films like Summer with Monika to his last directorial effort, Fanny and Alexander.

The paintings of Picasso, the music of Mahler and the films of Bergman. Priceless treasures from western modernism.

Bergman is a titan, a giant. No director comes close to the sheer quantity of such important films as Bergman, always thought provoking, hypnotic and prescient. A cinematic Titan in every sense of the word, Tarkovsky reckons him to be the greatest director ever.

I can see exactly where he’s coming from.

This does expose a certain side of the human psyche when made vulnerable, both from the perspective of caretaker and patient.

I watched Persona recently for the first time and I’m still not sure if I like it or not… I love the camerawork, editing and sound design, and the two actresses are fantastic but I think the mainly cerebral nature of the film left me a little cold. Not to say it isn’t emotional but maybe I just didn’t buy what the characters are doing in the film and how they both start “acting”.

Obviously this is part of the surreal nature of the film; that the protagonists emotions and questioning reality is brought to the extreme. Part of me thinks it could of gone further, maybe? I almost want to say the subject matter demands more drama and more insanity on screen like the crazy edits and more great scenes but then maybe more drama would take away from the sad eerie bipolar atmosphere of the film. As you can no doubt tell, I’m as stuck in two minds about the film as the characters in the film itself. I loved it technically but as a full experience it left me cold

Definitely gonna rewatch it at some point and maybe I’ll feel differently.

That was great. Thanks. I understand it more and appreciate it more thanks to your clear explanation. Cheers.

Those interested in this undoubted masterpiece are strongly recommended to read Susan Sontag’s fascinating 1967 essay on Persona. Stimulating as all her best work is, it provides fascinating perspectives on this magnificent film. I wouldn’t necessarily start my exploration of Bergman with Persona, but it is at the summit of his art.

I don’t get Bergman. I like ‘Autumn Sonata’ very much, a beautifully observed chamber piece with Ingrid Bergman’s incisive portrayal of the mother being particularly memorable. And ‘Silence’ has certain enigmatic intensity.

But ‘Persona’ … I find it too self-consciously ‘modern’. It is as if modernist techniques are used only for stylistic (everything is about showing or showing-off) or symbolic (everything has to mean something) ends.

I find the film impersonal and contrived. Maybe ‘Persona’ refers also to the director’s distancing of himself.

Yes, i feel the same way about this film too, although I love all the other Bergman movies i have seen. Something about Persona reminds me very much of Godard’s film-making style: “self-consciously ‘modern'”, “impersonal and contrived.” (like Breathless).

This is one of the most frightening films I’ve ever seen. I thought so when I saw it first around twenty years ago. I rewatched it again several years ago thinking that perhaps I’d just been young and impressionable first time around. No. It is still terrifying.

Not one to watch if you’ve ever felt any anxiety about your identity or your mental equilibrium.

I suspect you’re right there. Not recommended for anyone feeling a bit shakey.

I didn’t find it terrifying though, myself. That’s interesting.

A film I’m unfamiliar with. One to add to the watchlist.

Thanks for the article and I look forward to many more about groundbreaking films and art.

By far and away my favourite ‘Bergman’ film is ‘Die Duve’:

Love this film. It tells a story in an investigative and philosophical manner.

There are investigations around the role of the female in western society, the attempt to deal with oppression, and an atmosphere heavy with political overtones, which all resonate in our climate with reference to gender issues.

Beautiful and disturbing.

Persona is a classic 60s movie and Bergman uses two of his greatest artists enigmatically as if he was taking their acting ability in the abstact and shoot it as a silent movie (albeit with a little talk). I still think it doesn’t quiet come off and I can’t accept any explanations given for the film.

The images are to shock and disrupt but they never take root: more like a philosophical overlay.

I will watch it again and again until something ‘happens’ to make me realise the meaning.

This is one film I admire way more than I love. Every time I watch it, I am taken by its revolutionary narrative and filming techniques and the acting, but seldom bowled over like I am by Wild Strawberries or Fanny & Alexander. Maybe it’s the eeriness.

Personally, I used to be a “Silence” man, but with the years and the repeated viewings on DVD, I’ve switched to “Through a Glass Darkly”. I think it’s Bergman at his most nihilistic and depressive best.

But hey, we’re really nitpicking our personal choiced in such a cave of treasures that it would turn Ali Baba green with envy: from “The Seventh Seal” (1957) to “Fanny and Alexander” (1982), the man has given us a whole catalogue of incredible masterpieces. So “Persona” is too abstract, or too meta -the use the current lingo- for some? Who cares? There’s plenty more stuff available, and the artistic level is always interesting and thought provoking, at the very least.

That is what is called being a true master.

I have seen most of the films of Bergman but not Persona. I borrowed the DVDs from the local library. Also I have been with friends to see Silence in a movie theatre but his films can be watched from a smaller screen I felt at home. They leave you speechless. Every subject he touches he transforms. He transfers you to any place. Every persona dramatis in his films is effortlessly real. All his actresses and actors are superbly natural. I feel this is a film one must prepare himself or herself to see, like becoming Bergman’s guest, sitting with him at the table listening to him; it must be seen many times and though about for very long in silence before one talks about it.

Persona is one of the first Bergman films I watched along with The Hour of the Wolf and The Passion of Anna and I thought (then in my early 20s) that the film medium is more than just a way of telling stories using a series of images…Persona is one of my favorites…I was ‘discovering’ Truffaut and Fellini about the same time and then quit watching popular cinema altogether for some years after…

Persona is the film I have watched more often than any other. I was first drawn to to it by the physical attractivenss of Ullman and Andersson – I was 23 in 1966 – but the strange engaging power of the film, and the fascination of the disturbances to which it alludes, have drawn and held my attention and wonderment. Beauty x 2 + an abyss beyond fathoming.

It is the greatest examination of human emotion ever put on screen.

I think this movie shows the aspect and question of oneself. The question arises more often in the movie if the idols of oneself really resemble the truth or ‘your truth’. So its a question about truth and lies. And the truth is foremost subjective and can be adapted to fit your values. The movie starts with the camera roll and stops with the camera roll, which can be interpreted in various ways. One could be the question of what is real and what is not related to the values of a person. Anyhow, this is just a small idea on the side if it might be related to the values of a person and the persona this person can resemble sometimes.

I’m really glad you took the time to analyse this masterpiece. It’s one of my all time favorite films and is a timeless classic. Bergman made so many great films, but this one is definitely on another level.

My thoughts : I have the feeling that Elizabeth, as an actress is presenting performances that can help the audience make sense of the world, while she herself is laying herself bare. I think it is no accident that she dries up during a performance of Elektra, as she realises that there are horrors than can never be articulated, never explained, so she decides, like the audience, to become an observer, to try to move closer to truth and understanding. An audience doesn’t interrogate the players or the play, she does likewise in her observation of Alma, now the actress in her personal drama, her one woman show. I think many of the films themes develop naturally from an idea like this. But hey, maybe Bergman never had that idea, but it’s great that a film like this encourages so many interpretations. It’s endlessly fascinating.

I respect Bergman, but I think a great film is made with the right amount of many things in perfect balance, and Persona is way too far from it.

Bergman was the master of Swedish Cinema, and one of the top players in world cinema. Persona is, in my humble opinion, the greatest film ever made.

Thanks Ka Man Chung for a beautiful analysis and thanks indeed to The Artifice. It’s a real treat.

Just got done watching persona, I loved it. The monologue Alma has about her sexual experience at the beach was absolutely stunning I felt I was in the room listening to the story.

That was one of the most sexual scenes I’ve seen in my life. No nudity, just a woman recounting her story. Bergman’s storytelling technique was absolutely brilliant.

I feel like Elizabeth is everything Alma wants to be, Fight Club kinda thing

Bergman’s films are all unremittingly uncompromising. This makes them harsh and harrowing, a therapeutic experience as opposed to entertainment. My personal favourite is Scenes from a Marriage.

The greatest free form creative achievement by a cinematic auteur, an abstract artistic masterpiece without parrellel.

Bergman is definitely a master and ‘Persona’ is also a masterpiece.

On the spectrum of arthouse to mainstream, no matter how much I appreciate the genius of Bergman (Through a Glass Darkly is my favourite due to its deconstruction of mental health and religious delusion), I can also relate to those that mock the pretensions found in the high-brow film scene. Bergman may be an acquired taste, but I’m still into it.

Indeed. When I saw some of the parodies (such as this: https://www.ingmarbergman.se/en/universe/popular-culture-part-1-parodies) I couldn’t stop laughing!

This was really interesting, I will have to watch it!

Bergmann has so refined his art so that it has become attractively disinteresting.

I’ve watched it over 50 times in the last 30 years and still learn something new each time. Still trying to figure out a few things.

Profound insight on this deliciously layered piece of art.

I’ve only seen four Bergman films. I want to see this one

Such a fantastic breakdown of the film, I’m torn after having watched it on what to think of my own reality!

It is one of my favourite movies. An absolute masterpiece, but I am a Bergman fan.

Such a nice review and analysis of this excellent film. After reading this, it makes me to watch the film once more…Thanks.

Great analysis. I love the way the film dives into the ideology of representing two sides to one individual and how the two different personalities of each character is able to intertwine and wrap themselves into one.