Phantom Thread: The House That Always Changes

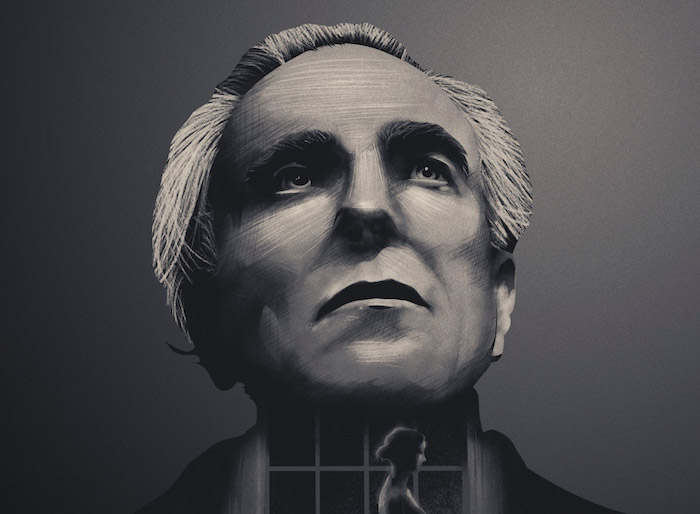

Around the midway point of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread (2017), Daniel Day-Lewis’s Reynolds Woodcock finally comes around to displaying a bit of growth. From living within his plush comfort zone for decades, he reluctantly succumbs to the ideas of changing things up – and dare he say it – move with the times. This doesn’t mean he’s going to suddenly become a ‘chic’ designer, because as he makes abundantly clear, he “doesn’t even know what that word fucking means.”

But instead, the addition of his new muse Alma (Vicki Krieps) has brought some much-needed disruption to his militarily observed routines and he’s starting to see what life can be like when he isn’t so incredibly consumed with his work. Displaying a previously inconceivable openness, Reynolds says “a house that doesn’t change is a dead house.”

And that sentiment is what makes the movie as a whole feel so vibrant. Phantom Thread, like many of Anderson’s other movies, feels fresh regardless of how many times you watch it because of how often it keeps you on your toes – the way it constantly ‘changes’. Whether those changes are within the narrative, to the broad genre of romance, or in the accepted dichotomy of ‘how things were’ in this slice of British period life – each of them contributes to a unique experience when watching the film.

The Reversal of Romantic Archetypes

For those who haven’t seen the movie, here is a brief synopsis of the Romance/Drama – “Renowned dressmaker Reynolds Woodcock and his sister Cyril are at the centre of British fashion in 1950s London — dressing royalty, movie stars, heiresses, socialites and debutantes. Women come and go in Woodcock’s life, providing the confirmed bachelor with inspiration and companionship. His carefully tailored existence soon gets disrupted by Alma, a young and strong-willed woman who becomes his muse and lover.”

In most romances, there are clear romantic archetypes for characters to embody. Think Jack in Titanic as the lovable street urchin who has ideas above his station. Think of sweet, sugary Ally in The Notebook who doesn’t really have many personality-defining traits other than being a beacon of good. And for a more literal reading think of the eponymous Ruby Sparks, who is literally written into existence as one archetype before developing her own sense of self. A similar thing happens in Phantom Thread, albeit, more organically.

In fact, when it comes to shifting character types, both Reynolds and Alma are great case studies. We open the movie with Alma describing how “demanding” Reynolds can be when he’s healthy, talking with maternal wisdom as if she has total control over him. And although this motherly attitude will come to the fore later in the narrative, this view of Alma in charge is almost immediately dispelled the minute we’re introduced to Reynolds.

Much of Reynolds’s actions throughout the narrative leave an impression that he’s the ultimate soft-spoken stereotype in toxic masculinity, but that’s at odds with the first time we set eyes on him.

Going through his extensive morning grooming routine as he primps and preens himself to near perfection, this introduction to Reynolds is a sequence we’re more used to seeing from the female perspective. Whether it’s trying on 100 new outfits or a makeover from plain Jane to the princess, this ritualistic montage is usually a prime marker of romance movies used to set out the love interest as someone worth pursuing. Using this setpiece for Daniel Day-Lewis’s character is a perfect encapsulation of Anderson shifting gender expectations right from the off – presenting Reynolds as the desired beauty.

Another hallmark of the female love interest in many movies is a gatekeeper, a best friend, a fiance, a father, etc… Someone who acts as a barrier to the protagonists’ true love blossoming. And that’s a role (one of many) that Lesley Manville’s character, Cyril, plays for her on-screen brother. Acting as an emotional bodyguard for Reynolds’s feelings, we see her assume this role very early on by asking his lover of the time, Joanna, to leave. Dealing with the messy business of breakups so Reynolds, the gilded, protected genius, doesn’t have to. And when Alma arrives into Reynolds, and by association Cyril’s, life – she has to jump through all the same familiar hoops we’ve seen countless protective fathers do for their precious daughters in other romances.

But, true to form, Anderson doesn’t let this impression of Reynolds sit for long, converting Woodcock back into a more familiar ‘masculine’ role. Upon meeting Alma in the hotel she’s working at, the old powers come into play and Reynolds turns his male gaze to the young waitress, putting on his best charm offensive.

When Reynolds is in this mood, she feels love so all-encompassing that everything else pales into insignificance. She says “to be in love with him makes life no great mystery.” And while the relationship stays as such, so does this more traditional power dynamic. But as we know, it doesn’t.

When Reynolds reaches the end of his usual relationship cycle with Alma, he seems ready to break it off with his new muse. Fearing this, she hatches a scheme to keep her man within her grasp – turning her from the sweet little dependent to the in-control aggressor that we were introduced to in the film’s very first flash-forward scene. Pendulous as always, this causes Anderson to redraw Reynolds once more, this time as an infantilised and emasculated charge who is completely reliant on Alma. Turning the lovers into a mother-son dynamic, something which is even more intimate for Reynolds given his idolisation of his dearly departed mum.

One Score, Two Genres

Even though his command and consequent challenging of romantic archetypes is a pretty big genre hallmark, there are numerous darker elements which paint a picture closer to a psychological drama. A key element that makes this high-wire act so successful is the score by Jonny Greenwood, which, taking a cue from Anderson, changes from scene to scene to create an air of uncertainty.

In the aforementioned opening scene where Alma is describing how demanding Reynolds can be, the music matches the action with an unnerving discord serving to create an incredible amount of tension. And considering how early on in the movie it is, we really have no idea why or where it’s going.

It isn’t until 25 minutes in (and 10 minutes into Reynolds and Alma’s first meeting) that the looming presence of the music turns into the orchestral swoons that colour the pair’s burgeoning relationship. Elegant, grand, and intoxicatingly romantic, Greenwood’s score turns the potentially awkward situation of a dress fitting into a love affair, although considering these exquisite melodies are mostly reserved for scenes of Reynolds designing dresses – you do wonder whether the love affair is between Reynolds and Alma, or just the dressmaker and his passion.

It’s not just that separate pieces of Greenwood’s score set this disparate tone in different parts of the movie, they actually coexist in the same piece of music. In both The Tailor of Fitzrovia and Alma, we hear swooning starts give way to bittersweet and tension-tinged endings, while the main theme of House of Woodcock has a brief interlude of darkness between its saccharine beginning and ends – all of which echo the tonally contrasting film.

This wonderful juxtaposition by Greenwood not only works within the confines of the narrative but it also showcases the combustible nature of Reynolds himself. When he’s in love and sweetness personified, it’s as if the whole sun is shining on Alma. But when he’s focused on work and set in his stubborn ways, she can’t see a single ray behind the gathering clouds.

Always the Bride-maker, Never the Bride

One of the more obvious changes in the movie is another which isn’t shown by one large, demonstrable deviation, but instead by a changing pattern of behaviours. Reynolds attests very early on, he’s a “confirmed bachelor” and that he quite enjoys it that way. In fact, some of the very first scenes we’re treated to with this creature of habit are the dissolution of his previous relationship with Joanna. A tryst which has clearly run its course, we’re left to imagine that even their relationship would have started as brightly as his and Alma’s.

But throughout Reynolds and Alma’s affair, we see him almost simultaneously giving into his well-worn cycle and looking as if he wants to dispel it. He spends a lot of their first date telling Alma he’s “strong”, only for her to claim he’s just “acting strong”. And then later in the movie, when he’s feeling anything but strong – the only person he wants near him is Alma. He’s somewhat subconsciously letting his guard down, his actions informing her that she was right.

In that same early exchange, Reynolds goes out of his way to dash Alma’s hopes before they’ve even had a chance to be built up – saying “I think it’s the expectations and assumptions of others that cause heartache.” Essentially, warning her against any ambitions of turning their fling into something more permanent. But the problem with those words is that they lose their meaning when they’re so at odds with his actions.

Reynolds whisks Alma away from her low-paying job as a waitress and gives her a taste of the high life, something she’s never been witness to before. It’s clear that Reynolds is either conveniently deaf to Alma’s request of “whatever you do, do it carefully”, or actively ignoring it. For him, there is no careful. It’s all or nothing. Or perhaps, more aptly – at first, all. And then nothing.

By impossibly tangling her up in every aspect of his life, Reynolds makes the likelihood of their relationship ending in heartache for Alma highly probable. Something which is only avoided by Alma’s own, admittedly extreme, actions.

One Man’s Tea is Another Man’s Poison

Sensing the end is nigh for Alma with Reynolds’s irritability approaching its peak, including eating stodgy foods which he’d previously banished from his diet when he broke it off with Joanna, Cyril asks if he’d like her to get rid of Alma. To her surprise, he declines. But the very fact that she asked the question shows how reluctant to change Reynolds usually is, which makes his wish to keep Alma around all the more impressive. Even before Alma poisons Reynolds’s tea to turn him into a dependent, he can see there’s something different with his current beau – and even though he can’t quite put his calloused finger on it, he’s willing to let it ride out a little longer.

After the first round of poisoning, Reynolds wakes up an apparent new man. He comes down to find an exhausted Alma, who has been pulling double duties of taking care of him like a surrogate mother and helping repair the ruined dress, and gets carried away with the moment. He proposes to her and she is so clearly taken aback that it takes a while for her to even acknowledge it. This is perhaps because, once more, Reynolds’s actions are at odds with his words. He doesn’t have a ring. He clearly hasn’t thought about it before. And he doesn’t even get down on one knee.

The way Anderson stages Reynolds in comparison to Alma is an interesting point to note throughout the movie. Yes, Reynolds is the dressmaker and Alma the model, which means he at some point has to bend down and tend to the lower parts of the dress, but most of the action we see in these exchanges keeps Reynolds, at the very least, as Alma’s equal. In fact, our attention is drawn to this in an earlier scene when Woodcock and his dresses are the subjects of a photo shoot.

The photographer asks Reynolds to get on the floor and look up at Alma and he is completely against the idea. Eventually and reluctantly fulfilling this duty, he complains about it the whole time and stands back up almost instantly. He clearly doesn’t think he should be beneath Alma. So, when the proposal comes around and Reynolds is Alma’s physical equal – sat at the exact same level as her – it’s notable both for how this situation has somewhat improved that he doesn’t have to be above her. But it’s also notable that he doesn’t want to get down on one knee and show complete deference to her.

Once again, he’s acting a certain way that’s at odds with his words. It’s only the film’s last scene where Reynolds finally allows himself to be beneath his wife as he makes her another dress. It’s here, knelt at her feet that he eventually pays her the respect she’s earned. Albeit, after another round of poisoning,

Let’s Get Physical

A final point of interest in relation to changes within Phantom Thread is the way Anderson uses physical change to bring out a change of emotions, habits, and overall demeanours in Reynolds. Firstly, it’s in the locations.

When we’re introduced to Reynolds he’s at the end of his relationship with Joanna in London, and he’s clearly finding it a little stifling. Following the advice of his sister, he packs up his things, loads up the sports car, and drives to a completely new destination in the country. But it’s not just the scenery that changes, it’s him. He becomes jovial, full of life, and really rather charming. He exhibits that well-known behaviour of a social chameleon. Away from work, he emerges from his cocoon as a more sociable, easygoing character. And yes, we might think that it’s Alma doing this to him after their meet-cute goes so well, but considering he quickly returns to his curmudgeonly old self back in London with Alma in tow – it seems that it was the location doing the bulk of the heavy lifting.

Another physical change that brings out different sides of Reynolds is his attire. We know that he sews secret messages and mementoes into his clothes when he tells Alma about the lock of his mum’s hair in his suit’s breast. So, it’s unsurprising to see that when Reynolds has got his suits on, he feels as if he’s protected. With his mum close by, he feels safer.

When Alma ambushes Reynolds with a surprise date and he instead elects to have a bath first, he comes down to the date in his pyjamas. But that’s not all, he rather strangely has his waistcoat and blazer over the top of them. At first, this can simply be read as Reynolds showing reticence to his new lover and her surprise, bringing to mind a line from Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network – “you have the bare minimum of my attention.”

But it’s more than that. Remembering the fact that his Mum is sewn into his clothing, his attire is no longer just a suit, it’s a suit of armour. It’s his protection. All the scenes where Reynolds is showing his weaker, vulnerable side to Alma, he’s stripped of this armour, wearing only his pyjamas. Leaving Alma the opportunity to swoop in and play caregiver. Meaning her role changes once more, from lover to mother.

Even though Reynolds Woodcock shows a complete distaste for change, Paul Thomas Anderson shares none of his concerns with Phantom Thread. A movie in constant motion, it’s never entirely clear what one character wants or doesn’t want. And that’s what makes it so thrilling. Repeat watches of this movie can have you thinking it’s an elegant romance dressed up as a psychological drama, or alternatively, a psychological drama about codependency with delusions of romance. Or both. That’s the beauty of it, it changes with each viewing. It all depends on which phantom thread you want to pull hardest at.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The only film I can think of closest to this unusual project was Neil Jordan’s adaptation of Greene’s The End of the Affair. I believe the influence is clear but Anderson achieves a triumphant rather than tragic conclusion thanks to the stand-out performance of the young Belgian actress, playing Lewis’ lover then wife.

He also conveys a subtle complicity between the two women (the 2nd being the spoilt genius’ stoic sister) which makes this a lighter and more human companion piece to his other great directorial triumphant “The Master” – a complicity that Phoenix and Seymour Hoffman also share as a rather darker mirror to this (other) period love story.

An excellent analysis of a sublime film.

At the film’s conclusion, I was bored with these characters, which is not the desired response for a storyteller. Once upon a time, as in Magnolia, PTA could create idiosyncratic flawed personalities who held one’s interest until the end and beyond. Alma and Reynolds are as dull as ditch water.

Multi layered brilliance- works as a romantic drama with off kilter humour as well as some actual LOLs- and it’s uncomfortably truthful and insightful on relationships too.

Plus, it’s wonderfully acted and the soundtrack’s a dream, (in fact it’s almost another brilliant, memorable character, in itself ). Wonderful.

The character Alma seems a bit disturbing. Probably the reason behind her cinematic allure.

I remember feeling quite struck by this film. It veered off into directions I had not at all anticipated from the initial trailer. It’s a film that certainly stays with you.

This is a fantastic film, the best I have seen in the last few years.

A tremendous film; a real treat. It’s somehow thrilling when American directors like Losey and Kubrick can come over here, work with experienced British actors, and perhaps see and bring out things that our native eyes miss and I couldn’t detect a false note in this film. It’s also a thrill when you get that early moment in a movie when you’re completely sold and know, with total certainty, that you’re going to love what’s coming for the next two hours or so and here, for me, it was that first meeting between Alma and Reynolds. You lean back, with a feeling of extra comfort, and let it all wash over you. Splendid work by the bloke from Radiohead too.

i had the exact same experience re: that moment. felt like i was in safe hands – as if i didn’t know that already

I thought Vicky Krieps was magnificent – a new Greta Garbo and charm personified.

Love how PTA turns the older man/ younger woman power game on its head- and what about that strange eastern european looking country house?- like a place from a dark enchanted fairytale rather than solid english countryside -and those weirdly filmed car journeys – seeming to travel more than just physical distances.

I’ve seen so many similar relationships of a man subjugated to his mother who never grows up and then plays games with woman ever after — unable to commit to anyone not as cruel as the bitch who bore and raised him. The outcome is perhaps bachelorhood but — in this case — Reynolds swears he’s waited all his life to meet the waitress who can remember a ridiculously-long list of breakfast food and how he likes it. But what seems truly arresting to him is her pronouncement that if he wants to stare her down, he will lose.

And so the contest begins and he’s apparently losing interest [as he always does] when she insists that a client who passed out in one of his dresses “doesn’t deserve it” and that they should go into her home and strip her of the gown. THIS is spectacular to him and, I believe, that’s the moment he realises he’s FINALLY met someone as cruel as his own mother, as humiliating and terrifying. And suddenly he wants marriage and declares “love” which is actually just a sick need.

And from the incident she discovers how to conquer and hold him. It’s just a question of how vicious she’s willing to be. And — the perfect metaphor for the ultimately toxic relationship — she discovers a way to poison him with mushroom in a delicious meal that just about kills him, but not quite, rendering him helpless, submissive and beaten.

The apparent congruity with his childhood — of being emasculated but never quite flattened — is oh-so-familiar and comforting, allowing him to be revived and lash out into his creative world again and again, with the promise of being repeatedly humiliated and brought to his knees [quite literally] in a way that reminds him so of home-crap-home with his mother. To me it’s the perfect metaphor with near-lethal co-dependence that sooner or later will prove miscalculated and deadly. And the script builds in an incredible way — the clues having been there from nearly the first line.

What I found interesting was Woodcocks obsession with his dead mother.It seemed to me that after Alma poisoned him and then nursed him back to health the relationship became reminiscent of a mother caring for a sick child As such he identified it as true love. He enjoyed being infantilized.

But did you care enough about the character to even find that dynamic interesting? I got the Freudian replacement mother idea – it was advertised quite obviously early in the film. For me, the problem was just how dull, selfish and lifeless DDL’s character was – he had almost no redeeming qualities other than that ridiculously ambiguous posh accent. Why would Krieps wish to stay with such a man? Surely because of the money? If so, what does that make her? The two of them just seemed so shallow and lifeless. I’ll admit that Krieps acted very well, however.

exactly. in the end it is proved both of these people are no different from each other. Reynolds is openly abusive and Alma is just a wolf in sheep’s clothing. if she left him after the poisoning,it would’ve proved her noble character. after the second poisoning, she proved that she only cared for money. i think she got accustomed to luxury and now dont want to lose her life. its neither survival nor character. its pure selfishness. but i gotta say this. its a match made in hell

Phantom Thread’s greatest appeal comes from its sense of time and place. I loved it.

I found it, oddly, cruel – first from one perspective (to a certain point) and then another. Much preferred “The Master” and “TWBB” of recent times, and (my favourite, “Inherent Vice”).

Interesting comment re ‘cruel’. Do you not find The Master and TWBB very much about cruelty? Inherent Vice was far less so.

It had me in stitches.

It’s a great character study. It’s beautifully produced, acted and directed. The music is wonderful. The story is weak, however, and the ending is especially weak – I rolled my eyes when the pram appeared.

Some things I didn’t like about this film, I thought the improvised scenes, or the scenes where they talked over one another were not very natural. When Day-Lewis is asking whether she has brought a gun over and over again it really reminded me of a Will Ferrell type character, sort of Anchorman. And some bits were heavy handed, like when his sister sniffed Alma. Also, as with any of Day-Lewis’ performances, it was a tad self indulgent, the way he listed off all those items for breakfast when ordering from Alma, I felt like he really enjoyed acting the character, but to the point of almost being self-satisfied whilst doing it.

He ordered lots of food to symbolise his lust for her.

I loved it. I could see the point where Alma suddenly felt discarded, her purpose over, and it was astonishing what she did next. Totally did not see it coming.

I think Reynolds is also seen as someone past their best, his gowns seemed dated even for that time, with the threat of Dior in Paris promising a bold new look. Having said that, the gowns were spectacular.

Listened to Paul Thomas Anderson on Adam Buxton’s podcast a few years back and he honestly sounds like a right laugh to be around. Plus very insightful on how he and Day-Lewis work together. Worth a listen.

I enjoyed it a lot. It wasn’t what I expected, and wrong footed me in the direction it took, so it would be interesting to go back and see it with an idea of what it actually is, rather than “PT Anderson does costume drama”.

I loved it though will admit to being annoyed at the finale and Reynolds reaction/acceptance of Alma’s plans. Having never been able to get through either The Master or Inherent Vice but loving There Will Be Blood I was really pleased to like a PTA film as much again.

A very peculiar film and a treat for the senses. Act 2 is brilliant, but it does peter off towards a very unusual and darkly amusing end.

This is a superb movie. It feels like it’s been carved.

I love most of PTA’s stuff, but Phantom Thread was a film that just said nothing. Bland, sterile storytelling that offered just vignettes of upper-middle class life in post-war Britain. That’s pretty much it. Oh, and stuff about dress-making, if that’s your thing. Other than that, Daniel Day-Lewis chews the scenery for a couple of hours.

This is such a well written article and really sums up everything I felt about Phantom Thread. It was an utterly fascinating film and I was completely captivated.

This is the first PTA film I truly loved. Compelling from the first shot to – well, almost the last.

Am I the only one who thought the jaw-droppingly literal ending was…really…obvious?…I mean, talk about turning the subtext into the text…

Phantom Thread is a vapid exercise in watching Day-Lewis sewing. No story. No point.

I don’t think I’ve seen a true masterpiece since DDL and PTA teamed up in 2007 and created There Will Be Blood.

A simmering movie that hooked me through its script! Going to watch it again tonight. Thank you for the read.

Visually appealing, absorbing acting and a film thats like watching a great novel.

Fantastic film, what a great note for DDL to have ended on.

I like when authors don’t engage with comments.