Race and the Revived Dead: White Zombie and Night of the Living Dead

The contemporary Western zombie featured in novels, films, and television shows such as World War Z and The Walking Dead has been said to represent current American foreign anxieties, such as the War on Terror. But was the threat of foreign violence an influential reason for the public’s fascination with zombies during their early days in film? Directors Victor and Edward Halperin’s 1932 film White Zombie and George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead from 1968 both represent keystone films in the zombie genre: the former marks the first American zombie film, while the latter sets the stage for the modern understanding of zombie tropes.

Jeffery Cohen writes, “The monster’s body is a cultural body [that] signifies something other than itself.” 1 So what did the zombie represent in the 1930s and 1960s, and how has that influenced our contemporary interpretation of the flesh eating undead? This analysis will seek to understand how the zombie monster fits specifically in relation to the racial divides of each time period, including the U.S.’s foreign dealings with Haiti and their domestic issues during the Civil Rights Movement. This is not to say that the zombie figure was necessarily connected to race intentionally, as intention in texts is difficult to determine. Rather, this examination seeks to illustrate how the zombie engages with these social and political issues, intentionally or not. In analyzing the zombie’s relationship to race, we will find that the zombie simultaneously reinforces and critiques racial prejudice in the same way it is simultaneously dead and alive, or “living dead”—it defies and deconstructs social binaries, which has allowed it to last and evolve as much as it has over the past century.

White Zombie

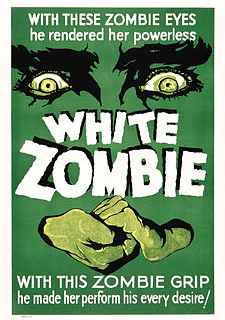

White Zombie is an American Pre-Code horror film, meaning it was released during the brief era before the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1934 that established guidelines surrounding sexual innuendo, profanity, violence, and other potentially offensive content. Though the film is Pre-Code, it is relatively tame in these aspects, especially by contemporary standards. The film did not receive favourable reviews at the time of its release: Frederic Smith of Commonweal described the film as “interesting only in measure of its complete failure,” and the New York World-Telegram stated: “The plot … is really ridiculous, but not so startlingly so as the acting.” 2 That being said, modern critics have since praised the film for its establishment of atmosphere, and it has developed its own cult standing as the first zombie film.

The advertising for the film at the time was highly racialized, as “exhibitors were encouraged to ‘hire several negroes’ to beat ‘tom toms’ while adorned in ‘tropical garments’” in front of a display with several “magic” props—including handcuffs—outside the theater. 3 This high contact advertising campaign involving “black magic and white bodies” 4 is the first indication of the film’s placement in reality—the horrors the audiences were about to witness were not bound within the cinema or even the realm of fantasy. This campaign particularly suited the film’s place in American-Haitian history, as it was released within the final two years of the States’ nineteen-year invasion and occupation of Haiti. At this time, there was a predominant cultural unconscious that could have easily connected the zombies of the film to the “colonial rule, unpaid slave labor, and the democratic injustices of American empire” in Haiti, and this was mirrored in the political world, as the “United States was finally beginning to withdraw from this unpopular and, by all accounts, unsuccessful mission of democracy when White Zombie opened.” 5

As a Gothic text, White Zombie sets its zombies in a highly Gothic space: the island gives a sense of isolation with little means of escape, and the exotic foreignness of the island effectively places the monster outside of America, where such things were perceived to not possibly occur. This setting alone introduces the film as inherently nationalistic. White Zombie’s nationalist message is further supported throughout the content of the film, such as when the protagonist, Neil, tells Dr. Bruner about the “corpses” and asks, “Surely you don’t believe it, do you?” to which Dr. Bruner responds, “No! … Haiti is full of nonsense and superstition.” 6 This contrast between the rational white men and the “prevailing stereotypes of the ‘backwards’ natives” is strikingly unoriginal in its support of “western imperialist superiority.” 7 The characters even emphasize the Haitians’ underdeveloped belief system by incorporating a sense of Gothic time, such as through Dr. Bruner’s explanation that “some of [their superstitions] can be traced back as far as ancient Egypt.” 8 Exposing the folly of the ancients is characteristic of a Gothic text, as is also seen in Frankenstein through Victor’s professor’s discouragement of his work on ancient alchemy as “nonsense.” 9

That being said, similarly to Frankenstein in how Victor’s research turns out to be horrifyingly correct, it is the natives who focus on ancient superstition who turn out to be right—the white man’s disbelief and superiority complex, in this case, reveals his folly, leaving room for critique of white nationalistic propaganda. In the same vein, the film has been read as “an indictment of the U.S. for its early twentieth-century occupation of the island nation,” 10 especially due to its timely release during the Great Depression. African-Americans arguably suffered the most during the Depression, as white men often called for all black people to be fired or no longer paid as long as white people were out of work. 11 It is no coincidence that the small percentage of people who remained economically steady during the Depression were white men who profited off the backs of black slaves, such as through U.S.-owned sweatshops that ran in Haiti during the occupation, and continue to run to the present day. 12 The film inhabits this political era and, by presenting the slave owner as the villain of the film, can also be said to effectively critique it.

But while it may be critical of the States’ involvement in Haiti, it also does not propose a solution to the issue. At times it even implies that nothing can be done, such as when Murder Legendre is asked, “What if [your slaves] regain their souls?” to which he responds, “That, my friend, will never be,” 13 implying an impossibility of a world without slavery. The end of the film further supports this notion when the slaves fall over the side of the cliff with their master—they are never freed, and the white characters never care to free them.

This is possibly due to one key connection between zombies and people of colour: the zombies in the film are described as “not men,” but rather “dead bodies,” 14 in the same way that people of colour have historically been perceived as less than human. This will also be seen in the analysis of Night of the Living Dead, as Ben is killed at the end because the “posse sees Ben as one of the Other, and as such fails to distinguish him as human.” 15 The zombie therefore inhabits an in-between space of dead and alive in a similar way that black people have inhabited an in-between space of fully human and black human, or even human and (perceived) animal. But while the plight of the zombie can be interpreted as similar to the plight of the African-American, that comparison is faulty in that zombies cannot feel any emotion—that is, they cannot recognize their persecution—and they are still portrayed as the monster of the narrative. This connection reveals how White Zombie can serve as both a reinforcement and critique of American racial prejudice and colonial rule.

Night of the Living Dead

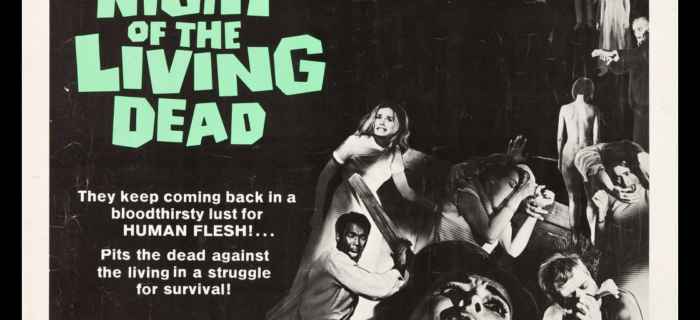

Unlike White Zombie, Romero’s 1968 American independent horror film was both controversial and highly successful in its time, and remains influential to this day. Part of its controversy surrounded its heavy use of gore and violence and public concern over children’s viewing, due to its release just before the Motion Picture Association of America began rating films. A Variety critique of the film called it an “orgy of sadism” and called for the Supreme Court to establish “clear-cut guidelines for the pornography of violence.” 16 Despite this controversy, five years later Night of the Living Dead was the “most profitable horror film ever … produced outside the walls of a major studio.” 17

Romero claims he drew inspiration from Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend for the film—a novel surrounding vampire-like creatures that plague the earth and prey on humans. 18 Similarly to I Am Legend, Romero never calls his monsters zombies, but rather “ghouls,” as he argued that they were so dissimilar from the Haitian concept of zombies that they were “something completely new.” 19 That being said, audiences began referring to them as “zombies,” so Romero eventually accepted this term in his sequels to the film, marking his trilogy as a keystone for the domesticated American zombie character despite their original more fluid identity.

Night of the Living Dead is especially significant for its time due to its casting of a black man as the lead role. Romero claims he did not intend for the role to be played by a person of colour, but intended or not, the role was resonant for audiences who were living during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. 20 Ben’s murder at the end by a group of rural American white men hunting zombies was especially poignant, as Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination was only months previous to its release. Despite Romero’s lack of intentions regarding the film’s commentary on race, his choice to cast a black actor led to “the film [being played] in more inner-city theatres than in white and affluent theatres.” 21 This fact alone reveals how racialized and racially divided the first contemporary zombie film came to be, despite the director’s intentions.

While Night of the Living Dead, like White Zombie, sets its story in a claustrophobic, isolated Gothic space of farmland—that is, far from civilization and any form of assistance in an emergency—rural Pennsylvania is far closer to home for American audiences than Haiti. Romero’s placement of the tale within the American border already opens up the potential for social critique, as it emphasizes that the danger can come from within the American public, not outside of it. Romero makes this setting clear from the beginning of the film with a close-up shot of an American flag in the graveyard, which serves as a reminder that even in death, one cannot escape their political landscape. There is also possibly an implication that the actions of the zombies, who come from American earth, can also be interpreted politically, as will be expanded on later. This concept of the domestic as monstrous is further emphasized within the home where most of the film takes place. There is a question and debate in the film over which tactic is safer: to move deeper within the home and claustrophobic space of the basement, or to stay upstairs where there is more risk, but also the possibility of escape, which preserves a sense of freedom. What makes this film particularly horrific is that the answer to this debate is neither; the white man’s daughter in the basement becomes a zombie, and the zombies outside eventually break in and takeover the main level. In this way, the film reveals how insidious the dangers occurring on American soil—such as the growing violence against African-Americans during the Civil Rights Movement—can become, as households are disturbed and places of respite from politics grow virtually non-existent. The iconic, full-screen scene of one zombie breaking a car window with a brick in order to get to the helpless Barbra is the ultimate image of the film’s critique that real-life horrors cannot be escaped, and that the film’s fourth wall is meant to be broken so that audiences may reflect on how the plot of the film relates to the politics of their everyday life.

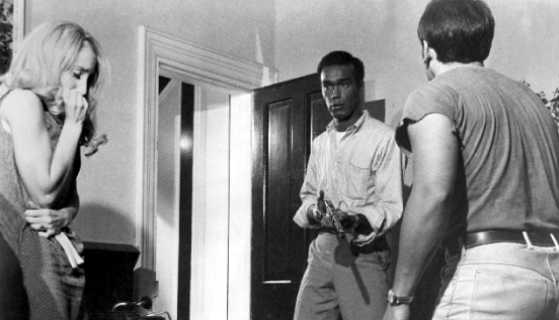

One notable way that Romero’s film can be seen to simultaneously reinforce and critique racial stereotypes is through analysing Ben’s relationship with Barbra. To begin, simply the fact that Romero paired the lead—who is often also characterized as both the hero and the romantic lead, either implicitly or explicitly—as a black man with a white woman reveals how the film is comfortable with playing with taboos, in this case the taboo of interracial coupling. While this may immediately appear to reveal the progressiveness of the film, it is important to analyse the nuances of their interactions before making such a judgement call. One scene to consider is when Ben attempts to reason Barbra out of her delusional state, and when reason fails, he grabs her by the shoulders and shakes her. On one hand, this scene can be seen as a display of the public’s anxieties around their perception of black men’s violent interests in and power over white women—a stereotype that has been used for centuries to support the oppression of and violence against African-American men. On the other hand, Ben only does this out of concern for her, not out of a bought of rage, as seen by how he “quickly subverts this aggression by providing compassion and concern.” 22

Also, the fact that he is portrayed as the rational one between the two of them further reveals that he is not prone to irrational rage; it is quite the opposite, as his moments of violence throughout the film are calculated and methodical. The same concept occurs later in the film when Ben is faced with Harry, a white man who increasingly thirsts for dominance over the household. Harry’s craving for power culminates when he threatens Ben with a rifle and Ben is forced to kill him, which is an act of “the ultimate demonstration of black rage.” 23 That being said, he does this out of protection for both himself and the women, which further reinforces his superior rational sense compared to the other white characters. While this multiplicity of possible interpretations of Ben’s actions were not intended by Romero, since they would not be so ground-breaking when performed by a white man, they are still pertinent in understanding how Night of the Living Dead disrupts stereotypes and binaries when it comes to whiteness versus blackness.

How the zombies are characterized in the film also upholds this concept of binary disruption in relation to race. One critical distinction that is made between humans and zombies is the question of mind versus brain: at one point the zombies are referred to as “mindless bodies,” and at another point they are called “bodies with reactivated brains.” 24 This question of how a zombie can have both an active brain and be “mindless” is mirrored by the previously discussed notion of Ben being both African-American and also the most rational person in the group. In the same way that Romero breaks the binary of mind-as-thoughtful-self versus brain-as-physical-conductor, the film also disrupts the racist idea of white-as-civilized/rational versus black-as-primitive/irrational.

There is also a connection here to W. E. B. DuBois’ double consciousness, which illustrates the difficulty of the African-American in being both an American and a black person—a binary of identity that cannot be inherently separated, in the same way the mind cannot be entirely separated from the brain. The zombies represent almost a form of ideal equality in the sense that “revivified death conveniently obscures racial, class, and gender differences” 25 in a much different way to White Zombie’s highly racialized black slaves. Instead, they all simply share the same craving: human flesh, of any race or gender. In terms of desire, the zombies of Night of the Living Dead can therefore be seen to represent the 1968 American longing for solidarity and a disruption of binaries—such as left versus right or black versus white—during a time of vast social and political change.

Since the 1930s, the zombie has evolved from the Haitian concept of the hypnotized slave to the American adaptation of the flesh eating undead. Throughout this change, one characteristic that has remained the same is the zombie’s connection to race and racial controversies. Each film’s sense of Gothic setting, interactions between the characters, and complex portrayal of what exactly a zombie is reveals and complicates the social and political contexts of each time period’s understanding of race. As a vehicle that can be used to both reinforce and critique racial prejudice, Steven Shaviro argues that the zombie is not only a “monstrous symptom of a violent, manipulative, exploitative society,” but also, “with [its] destructiveness and cannibalism, [a] ‘remedy for its ills.'” 26 The zombie’s cultural flexibility as an “uneducated ‘blank slate’” 27 is part of what makes it so appealing to audiences of different social contexts, which allows it to constantly revive from the pop culture graveyard. After all, though the monster may be defeated in the films, what it represents in reality—in the case of this analysis, racial stereotypes and divides—continues to remain very much alive.

Works Cited

- Cohen, Jeffrey Jerome. “Monster Culture (Seven Theses).” Monster Theory: Reading Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996. 3-25. PDF, p. 4. ↩

- Rhodes, Gary Don. White Zombie: Anatomy of a Horror Film. Jefferson: McFarland, 2001. EBook, p. 265, 267. ↩

- Fay, Jennifer. “Dead Subjectivity: White Zombie, Black Baghdad.” The New Centennial Review 8.1 (2008): 81-99. Project Muse. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 83. ↩

- Fay, Jennifer. “Dead Subjectivity: White Zombie, Black Baghdad.” The New Centennial Review 8.1 (2008): 81-99. Project Muse. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 83. ↩

- Fay, Jennifer. “Dead Subjectivity: White Zombie, Black Baghdad.” The New Centennial Review 8.1 (2008): 81-99. Project Muse. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 82. ↩

- White Zombie. Dir. Victor Halperin. Perf. Béla Lugosi, Madge Bellamy, Joseph Cawthorn. 1932. United Artists. YouTube. ↩

- Garland, Christopher. “Hollywood’s Haiti: Allegory, Crisis, and Intervention in The Serpent and the Rainbow and White Zombie.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 19.3 (2015): 273-83. Scholars Portal Journals. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 276. ↩

- White Zombie. Dir. Victor Halperin. Perf. Béla Lugosi, Madge Bellamy, Joseph Cawthorn. 1932. United Artists. YouTube. ↩

- Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. 1818. 3rd ed. Eds. D. L. Macdonald and Kathleen Scherf. Toronto: Broadview, 2012. Print, p. 74. ↩

- Garland, Christopher. “Hollywood’s Haiti: Allegory, Crisis, and Intervention in The Serpent and the Rainbow and White Zombie.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 19.3 (2015): 273-83. Scholars Portal Journals. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 277. ↩

- “African Americans, Impact of the Great Depression on.” U.S. History in Context. Gale. 2004. Web. 17 November 2017. ↩

- Garland, Christopher. “Hollywood’s Haiti: Allegory, Crisis, and Intervention in The Serpent and the Rainbow and White Zombie.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 19.3 (2015): 273-83. Scholars Portal Journals. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 278. ↩

- White Zombie. Dir. Victor Halperin. Perf. Béla Lugosi, Madge Bellamy, Joseph Cawthorn. 1932. United Artists. YouTube. ↩

- White Zombie. Dir. Victor Halperin. Perf. Béla Lugosi, Madge Bellamy, Joseph Cawthorn. 1932. United Artists. YouTube. ↩

- Berchilloy, Andre. Not Under My Roof: Interracial Relationships and Black Image in Post-World War II Film. MA Thesis, Northern Illinois University, 2015, p. 42. ↩

- Higashi, Sumiko. “Night of the Living Dead: A Horror Film About the Horrors of the Vietnam Era.” From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. Eds. Linda Dittmar and Gene Michaud. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990. EBook, p. 175. ↩

- McCullough, Paul. “A Pittsburgh Horror Story.” Take One 4.6 (1973). Web. 17 November 2017, p. 8. ↩

- Russo, John. The Complete Night of the Living Dead Filmbook. Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 1985. EBook, p. 6-7. ↩

- Robey, Tim. “George A Romero: Why I Don’t Like The Walking Dead.” The Telegraph 08 November 2013. ↩

- Jones, Alan. The Rough Guide to Horror Movies. London: Rough Guides, 2005. EBook, p. 118. ↩

- Berchilloy, Andre. Not Under My Roof: Interracial Relationships and Black Image in Post-World War II Film. MA Thesis, Northern Illinois University, 2015, p. 36. ↩

- Berchilloy, Andre. Not Under My Roof: Interracial Relationships and Black Image in Post-World War II Film. MA Thesis, Northern Illinois University, 2015, p. 40. ↩

- Berchilloy, Andre. Not Under My Roof: Interracial Relationships and Black Image in Post-World War II Film. MA Thesis, Northern Illinois University, 2015, p. 39. ↩

- Night of the Living Dead. Dir. George Romero. Perf. Duane Jones, Judith O’Dea. 1968. Image Ten. YouTube. ↩

- Fay, Jennifer. “Dead Subjectivity: White Zombie, Black Baghdad.” The New Centennial Review 8.1 (2008): 81-99. Project Muse. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 82. ↩

- Fay, Jennifer. “Dead Subjectivity: White Zombie, Black Baghdad.” The New Centennial Review 8.1 (2008): 81-99. Project Muse. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 81. ↩

- Garland, Christopher. “Hollywood’s Haiti: Allegory, Crisis, and Intervention in The Serpent and the Rainbow and White Zombie.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 19.3 (2015): 273-83. Scholars Portal Journals. Web. 17 November 2017, p. 278. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The thing about good zombie fiction (and I say this as someone who enjoys an awful lot of zombie fiction) is that the zombies are never the most horrific thing. Zombies don’t typically have the capacity for complex thought.

Zombie fiction is never really about zombies.

The politics of these masterpieces are subtle and implicit, but that emphasizes the cultural conflicts and pressures even more.

This is a very good point. We can see that racism in the United States is systemic and institutionalized because of the subtle way that racial violence creeps into the film.

Thanks for writing this. Horror directors rarely get the critical recognition.

This. It’s like we don’t believe they or their movies are capable of more. Which is ironic, since Romero’s main thesis was that it’s our beliefs that get us into trouble.

Romero claims not to have set out to explicitly discuss race, but the film’s racial imagery is quite apparent.

A very well discussed and researched paper that presents a number of great observations. In fact I will be quite interested to see what the next few years of zombie films will reflect about the current American climate. Great work!

I love your discussion of the different types of zombies, excellently researched. I would say there is also the new version of zombie that we have started to see with iZombie and Warm Bodies, where the humanity is being re-introduced to the zombie characters, I would be interested to see how they fit in to the bigger picture as well – what are the political and social implications of this change, why did this change happen. Regardless excellent piece!

Finally watched Night of the Living Dead, but was kind of disappointed (or at least underwhelmed) by it overall (slow and boring honestly) and as a zombie movie (not very scary – but maybe that’s because zombie movies have moved on).

Anyway, but what did impress me is the film as a racial allegory, so was surprised to hear director George A. Romero say that it wasn’t his intention at all. Now maybe that’s true and he just fell into it inadvertently when he unexpectedly cast an African American in the lead.

But whether intentional or not, it’s impossible to watch the movie without reading into it on that level. It’s amazing for 1968 to have a black man aggressively pushing around his fellow white survivors (including punching a woman), but also just the sight of him wailing into white zombie after white zombie. Sure, they’re zombies, but for much of the movie there isn’t much zombie-ish about the zombies – they mostly just look like spaced-out white folks. And they come from all walks of life – men-women, young-old, professional-blue collar – so you’ve got this sight of a black man just angrily beating up on wave after wave of a cross-section of white America. Striking!

And then at the end [MAJOR SPOILER], as order is being restored, you’ve got all the classic ingredients of a white lynch mob – led by the sheriff and his deputies, with their attack dogs and a posse of average white folks, everyone armed – all spreading out across the countryside in a search. If you showed someone that scene without any context, they’d think it was straight out of a ‘southern hunting down a black man’ movie. And at the end, they come upon him holed up in a house and mercilessly shoot him dead. Then there’s a long exposition of them, with meat hooks in hand, roughly grabbing his body and hauling it out like trash.

Of course, there is an explanation why they shoot him – the assumption that the house is just filled with zombies. And there is never any racism overtly expressed – either between the survivors in the house or among the posse. But the imagery of it is undeniable, whether intentional or not, and coming as it did in 1968 at the apex of the race question dominating everything in America, audiences could not have been anything but struck by it. And really, it is hard to believe that none of this ever crossed director George A. Romero’s mind. I have to wonder if he didn’t cheekily play it all up once he had his lead cast.

The power play between zombies and humans is eerily similar to that between marginalized peoples and Whites in the U.S.

So true. If we have learned anything from these zombie stories, it is that each and every small victory against evil is meaningful.

‘Night of the Living Dead’ was a horror film based on zombies. Of course some aspects of the film seem to have racial or political elements, but in the end, these seem unintentional rather than intentional. But still, it does offer a new and interesting perspective on the movie, even if it wasn’t intended to be seen in that way.

I learned my first lesson about race in America when watching NOTLD in the theater.

In Night of the Living Dead, Ben is African-American and the message I received when watching this was depressingly clear: They killed Ben because they believed a black man had to be a threat. A black hero equaled a dead hero.

To me, Ben was punished for his lack of deference to those determined to assert their own sense of superiority by any means necessary.

I feel bad for Romero. I remember an interview where he basically shrugged and said he couldn’t get money to make any movie that wasn’t “…of the Dead.” If I were an eccentric billionaire, I would absolutely bankroll that ivory trade movie he wanted to make for so long, or anything else he wanted to do.

The last 3 dead movies were the absolute shits. Romero did a great job introducing audiences to zombie films, but he needs to stay far away from it now. Zombies have completely lost any and all horror that they used to have, because of crap like Walking Dead.

I liked Diary of the Dead. The voiceover is mostly kind of awful, but if you can look past that the film has more to say about the found footage genre than most of its competitors. The characters seem torn between a moral obligation to preserve a record of their humanity and a voyeuristic impulse to get zombie-killing on camera. The film insists that “dead things are slow” because then there is time to recognize the residual humanity of the corpses between riddled with bullets and melted with acid.

I’ve loved Night of the Living Dead since childhood and I recall watching it for the millionth time one night and realizing one of the things that made me go back and see it again and again was the detailed journey it took us on. Nowadays attention spans are nonexistent and people get antsy over some dialogue or something not deemed gory and excessive all up in your face. I was never one to become seriously frightened by horror films from any era and would often watch stuff like “The Exorcist” alone at night when I was a kid, but those old films knew how to stir real fear in you AFTER you were done watching it. Going through that journey with the characters may not spook you as you’re watching it, but it sure as hell haunts you when you’re alone in the dark. That psychological aspect is all but gone from modern horror films, and all that’s left is sensationalist gore and other gimmickry.

Great post. I agree with the social commentary of the films.

It was such a gut punch seeing what happened to Ben when I saw it for the first time. He ended up making it through the night while everyone else around him dead. In the end, he was shot and killed by the police officers. It went to still pictures as they disposed of his body. The hooks they used was a striking image to me.

It might have been unintentional but George Romero tapped into something powerful in that movie with Ben.

Great films of satire and allegory to critique the ruling class.

What a good piece you have here.

Unfortunately, although the popularity of the zombie genre has increased in recent years, the strong black lead character is nowhere to be found in these more recent films. Instead of a Duane Jones, white megastars like Brad Pitt save the world from CGI zombies in films like World War Z. And even on television, it never seems to pan out with black men and zombies. We’ve all seen some of our favorite black male characters on The Walking Dead meet their fate.

Fantastic study of this topic.

I think that Will Smith in I Am Legend is a sort of a rebuttal to NOTLD.

What Romero really cared about was social justice, and that’s evident in his work.

It’s amazing that Romero’s simple casting decision still produces a powerful narrative effect 50 years after it was first done.

It was interesting to learn about the origins of zombies in film and be able to reflect on its relevance today. This was an insightful read.

I think you touched on an interesting point in that zombies (despite the fact that they are fairly consistent monsters in terms of appearance, strengths and weaknesses) have the ability to embody a variety of threats that are unique to a given time period. It seems that this ability to stay relevant at any point in time as well as the initial popularity and reputation of the genre has contributed to its longevity.

The discussion of the politics, particularly the racial politics that framed the immersion of the zombie movement are interesting and underdiscussed. Great work 🙂

Great essay, Im using it as an example for my students.

A good essay. I remember watching both movies. The interracial overtones of Night of the Living Dead certainly stood out at the time, since I saw it when it first came out. It is odd how seeing the movie again several years ago was, in some ways, boring since the interracial aspects mattered little. I think I realized that after years of seeing zombies in color and, perhaps, more sensational in action, had me contrasting this movie with more recent ones.