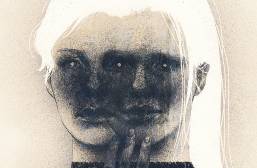

Repulsion: Sexual Repression, Mental Illness, and The Malevolence of Beauty

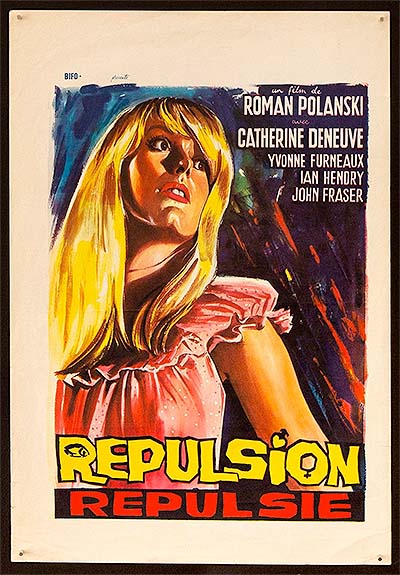

In 2024, Polish-born filmmaking legend Roman Polanski is still primarily known as a rapist who has been dodging authorities since the notorious, horrific sexual assault case at Jack Nicholson’s Hollywood mansion in 1975. This is despite his well-deserved Best Director Oscar for 2002’s The Pianist, and the fact that Rosemary’s Baby and Chinatown remain consensus masterpieces of American cinema. His first English-language work, 1965’s Repulsion, however, is perhaps his most chilling, raw, and unsettling film. Reared in Poland during Nazi occupation and a witness to the tragic murder of his pregnant wife Sharon Tate in 1969, Polanski’s filmography has unsurprisingly been tinged with portents of relentless pessimism and brutal violence.

Repulsion, starring the eternal French beauty and screen icon Catherine Deneuve, is graphic and uncompromising even by Polanski’s vaunted standards in this realm. For a film made the same year as Doctor Zhivago and The Sound of Music, the London-set character study is remarkable in its subtle restraint and unvarnished treatment of taboo material. It is also remarkably attuned to the tortured female psyche in a fashion matched only by Mia Farrow’s unforgettable performance in the aforementioned Rosemary’s Baby. A combination of Bergman’s probing analysis and Hitchcock’s nail-biting suspense, Repulsion is a film that appears stunningly contemporary in 2024, and is a rebuke to Polanski’s (understandable) detractors.

The Accidental Seduction of Fragile Beauty

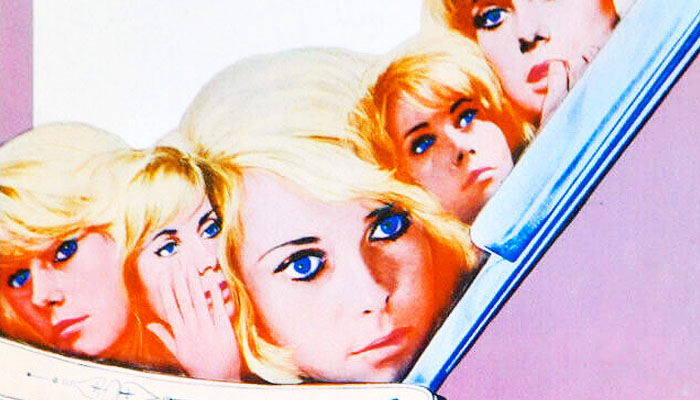

What is instantly discernible about Repulsion‘s enigmatic protagonist Carol, a Belgian-born hairstylist in “Swinging London,” is her almost inhuman beauty. As is typical in the film industry, Deneuve became more known for her porcelain features and tall, elegant figure than her considerable skills as an actress. Similarly, Carol’s physicality attracts a plethora of men of varying desirability, none of whom is interested in her personality. This is of course a common occurrence for both genders; surface attraction is the catalyst for romantic pursuance more often than not. However, in this lack of attention to the infrastructure of Carol’s mind, her would-be suitors fail to notice the profound warning signs in regard to Carol’s mental state.

The primary male chaser in the film is a dapper, clueless Londoner named Colin (John Fraser). Bragging about Carol’s picturesque blonde looks to equally socially inept pub-goers, Colin continues to ask a clearly disinterested Carol to dinner. Speaking to him in a flat, robotic monotone and failing to make an iota of eye contact, Carol conveys a sense of zombie-fied in-animation rather than sexual excitement.

This is a testament to the misleading seduction of beauty. The aesthetic appeal of Carol is so appealing and all-encompassing that it shuts off rationality and common sense in even the sharpest and most probing of minds. Her outward pleasingness endears her to her co-workers, despite transparent signs of aloofness and incompetence. Her own sister dismisses her younger, fairer sibling as slightly unusual, brushing off her lover’s warnings of the cracks visible beneath the hairdresser’s gleaming facade. This blindness relates to the fatal inability of many to discern subtle signs of mental illness that can brew and erupt in even the most docile and functional of human beings.

Mental Illness of an Age of Misunderstanding and Ill Treatment

The prevailing view of mental illness at the time of Repulsion‘s release can best be surmised by watching Frederick Wiseman’s stomach-churning, muckraking documentary classic Titticut Follies. A revelatory portrait of the practices of a typical mental facility in the mid-1960s, the patients are treated with all the mercy of violent, un-domesticated animals in the jungles of Zimbabwe. Three years before Roman Polanski’s film, the cult classic romance David and Lisa became a sensation among intellectuals and college students from Berkeley to Brooklyn. The film would be the first in a series of well-meaning but reductive cinematic portraits of mental illness. Subsequent endeavors in this ilk include the glossy romantic comedy Silver Linings Playbook, the cloying OCD romance As Good As it Gets, and even the hallowed One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. All of these films assert that mental illness consists of little more than misunderstood quirks, and that the afflicted can achieve romantic fulfillment and spiritual enlightenment through sheer hard work and a can-do attitude. Repulsion, while never coming close to diagnosing its severely damaged protagonist, is complex and realistic in its ambiguity and foreboding portrayal of mental disorders. In this fashion, Polanski’s cinematic vision is remarkably prescient, transcending its narrow status as a mere “psychological horror” film.

The signs of mental unrest in Carol’s psyche are as varied and multi-faceted as they are disconcerting. Many critics have diagnosed Carol as schizophrenic, and the reasons for doing so are not difficult to discern. She hallucinates strange men assaulting her in the middle of the evening, pictures cracks and disembodied hands appearing through her thin apartment walls, and hears unusual, unclassifiable sounds through the film’s 105 minute run-time. However, her subtler mental ticks imply other disorders.

One affliction Carol exhibits warning signs for is Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. The high-string hairstylist fixates on brushing her teeth and washing her body, gazes at microscopic imperfections in the kitchen, and twirls her fingers nervously in a compulsive, methodical fashion. As painful to watch as these Schizophrenic and OCD tendencies are, however, perhaps Carol’s most alarming (and ultimately fatal) disorder involves her inability to demonstrate and read social cues. Years before Autism and Asperger’s became mainstream diagnoses, the cryptic beauty Carol appears to convey neurodivergent perceptions of social awareness in a manner akin to the cognitive disability.

This manifestation of a social learning disorder does not contain the cutesy quirks and obsessions with comic books that mark the heroes of the simplistic sitcom The Big Bang Theory.

Rather than portraying otherwise lovable characters who simply have some anti-social tendencies, Polanski dares to depict a character whose disconnect from everyday socialization is alienating and disconcerting.

As aforementioned, Carol speaks in a flat, disconnected monotone that is similar to a common trait of those with Autism and Aspergers. Her obsessive nature may relate to this learning disability rather than an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Her failure to make eye contact and engage in socially accepted small talk with co-workers, acquaintances, and even her own sister likewise point to the Autistic spectrum.

All of these possible afflictions (with the notable exception of Schizophrenia) may have been properly treated, preventing the film’s gruesomely inevitable climax. However, the people surrounding Carol are blinded by her stunning physical attractiveness and apparent functionality, leading her considerable mental deficiencies to fester and explode like a raisin in the sun. As the lack of treatment and psychological support leads to violence and surreal bursts of terror, Polanski could be condemned as exploiting and sensationalizing the true-life ardors of mental illness.

Catherine Denueve’s grounded, stunningly lifelike performance and the small, vivid details imbued in the film lend a sense of realism which in lesser hands could be a schlocky William Castle-esque fright flick. These qualities make Repulsion the rare psychological thriller that delves into the protagonist’s subconscious with as much complexity and nuance as the construction of its horrifying story.

Sexual Repression Breeds Contempt

The final factor accounting for Carol’s unhinged personality is the film’s most controversial element, as well as being a recurring theme of Polanski’s notoriously psychosexual filmography. Despite her beauty and fashionista presentation, there is no concrete evidence that Carol has ever partaken in sexual intercourse. This is in striking contrast to Carol’s comparably plain but sexually voracious sister. In a chilling sequence, Carol writhes in discomfort and alienation as she overhears the orgiastic frenzy of her sister making passionate love to her partner. As strangers approach her on London’s bustling avenues with overtly sexual intentions, Carol’s first instinct is to withdraw in disgust. This parallels in many respects with her childlike, asexual personality. Despite being in her early 20s, Carol often conveys an air of pre-teen precocity and expresses an astounding sense of bemused wonder at the complexities of the modern world. Rather than an active participant in society, Carol cluelessly wanders through the rigors and ambiguities of existence in a surreal fashion similar to Lewis Caroll’s Alice.

This inability to engage with life manifests itself in her lack of interest, and even disdain towards, sexual activity. The only images in Polanski’s film pertaining to Carol’s sexual relations are of frightening nightmares of rape. In the opening minutes, a sleazy working-class brute (who looks oddly like a homelier Albert Finney) aggressively flirts with Carol as his enormous mouth seems poised to engulf her in a state of hyper-masculine hunger. As Carol is left to her own devices in a cramped apartment, allowing her mental state to deteriorate, her fertile subconsciousness imagines a hulking male lunging upon her bed and forcing himself on her screaming, frightened body. After a few repetitions of this hallucination, a discerning viewer will start to realize this one-off stranger is indeed the male she is envisioning in this disheartening recurring sequence.

Critics have attacked the vagueness of these sequences, arguing that the lack of concrete exposition of Carol’s history of sexuality makes light of the rape epidemic that afflicts females around the world. Although Polanski never completely spells out whether Carol was indeed raped in a past occurrence, this is due to the film’s documentary-like realism. The film never pauses for explanation or flashbacks; the film takes place seemingly in real time as the viewer watches Carol morph from slightly amiss to fully insane- and viciously homicidal. As aforementioned, Polanski refuses to outright diagnose Carol. This is the converse of the deadening finale of Hitchcock’s Psycho, in which a psychiatrist literally provides a diagnosis for Norman Bates, shattering any sense of ambiguity and probing mystery.

The closest the film comes to providing a culprit for Carol’s distaste for sex, and her mental state in general, is in the oft-discussed final frame. As the film fades to black, a quick, blink-and-you’ll miss it shot of a faded vintage photograph reveals the young Carol sneering in utter contempt at a male family member. The source of this animosity is unclear, but what is made clear is that the source of the protagonist’s repulsion started at a young age, and the 105 minutes are shocking psychological terror that preceded are given a bit of much-needed clarity. 60 years later, Repulsion continues to haunt and tease the viewer in its slowly building tension and psycho-sexual ambiguities.

Works cited

Baker, Emily Rose. “Sex and Psychosis: Roman Polanski’s Repulsion”

Holland, Norman. “Repulsion: Psychological Analysis” A Sharper Focus, https://asharperfocus.com/repulsio.htm.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Brilliant horrific film, the passing of time portrayed by the decomposing rabbit and the horrible scene where as a manicurist Catherine Denueve cuts the top of a womans finger off. I had an hard time sitting through it all but it was worth it. Cul de Sac ,another favourite film of mine . Polanski has made some great films.

I vividly remember sitting in my European Cinema class at University seven years ago while the lecturer showed a two minute clip from ‘Repulsion’ which showed a woman walking through the hallways of her house where dozens and dozens of outstretched arms lined the walls and the hands grabbed at her as she slowly walked past her. That two minute scene disturbed me so deeply I have never forgotten it and is the reason why I always shudder when I even hear the name of the film.

Can’t see myself sitting through the whole film somehow.

When discussing the matter of the representation of women in the films of Roman Polanski (or even the films of that director in general) the matter of pachyderms in the lounge must be given a degree of consideration.

Something scary about Polanski – the films have a quality which is more than filmatic or art – perhaps a kind of primal ritualism is deep at play – one characterized by a barbaric , even psychotic creeping prophetic sort of beat. It’s these elemental forces which break the cinematic mold and defines Polanski as an innovative mainstay contributor to film history but that said, it all still gives me the creeps a little.

He made some good films.

Wonderful analysis of one of his best films. Enjoyed this article immensely.

So how can a man be so hypocritical to make a movie like this while being a rapist himself?

The contents of this movie were disturbing to the point where I can’t bring myself to say I loved it, but it was a really good movie. Wasn’t a huge fan of the pacing, but considering the fact that it came out about 60 years ago and still holds up completely today is crazy. I’m not saying carols right I’m just saying I get it.

This movie seems to really understand the plight of women being viewed and treated as sexual objects with limited to no agency.

I thought it was largely a bore with ironic themes in hindsight for the director.

It’s interesting to see the evolution of psychotic break movies from Hitchcock’s Psycho to Castle’s Homicidal and I think Repulsion may be the best of them in its depiction of madness. Thanks for writing about it.

What an interesting film, with and without the context of who made it. it is also what alex garland’s men wishes it could’ve been.

Good analysis! Watch it with the volume turned up because the movie uses sound very well.

I too am also struggling with a case of lesbianism.

The best meditation on sexual trauma I’m aware of. A true masterclass on externalizing the internal.

Still some of the craziest camera work I’ve ever seen coming out of the 60s. An unintentional and ironically reclaimed feminist horror movie.

Great character study on the real horror motifs and tribulations. Fuk Roman tho.

‘Repulsion’ is the scariest horror film ever – and proof that you don’t need to rely on gore to frighten a viewer.

Yes, but since when did “gore” ever really “scare” a viewer? And who’s ever argued so?

Rabbit for supper tonight anyone?

I got excited about this until I realised it was made in 1965. I understand that all these horror classics are just that-classic. I often find it difficult to watch much older films being a child of the 80s.

And you actually admit as much ? My…

I am sure there will be a Saw sequel along any minute now.

Knife under the Water

Repulsion

Cul-de-sac

Rosemary’s Baby

Macbeth

Chinatown

Tess

Bitter Moon

The Pianist

All masterpieces, inevitably.

All of Polanski’s major works are about one thing and one thing alone: confinement – the helplessness and horror of being trapped by other forces beyond one’s control – whether in a yacht or a giant cruise ship, a flat in Kensington or the Dakota Building in New York, or Los Angeles in 1938 or the Warsaw ghetto.

I hate when movies remind me that roman polanski is a good director.

Great film-maker, ghastly human being. Further proof that God does not save the talent for nice people.

Polanski is the master of the single POV film ie Rosemary, Replusion, Chinatown, Pianist. Faye Dunaway is the center of Chinatown and she is superb.

Super ahead of it’s time, Polanski is a bit y’know but dude can make a movie.

Love this. You can tell it was shot by someone who knew what they were doing. It has a nice art house vibe with a cool UK 60’s beat.

Really cool paranoia film.

A horribly sad and empathetic movie made by a man who has done even worse things than all the men in this movie.

I need to stop watching Polanski films.

A little too real of a film!

art imitates life, i guess. it might be the saddest movie i’ve ever seen and it will haunt me for quite some time.

Catherine Deneuve is phenomenal. What a disturbing movie,

A deeply uncomfortable experience!

She’s soooo me (never wanting to leave her house or talk to men).

Everyone deserves a little catatonic schizophrenia as a treat.

Honestly one of the greatest movies of all time.

The movie is creepy!

so insightful!

Why? How?

It was a pleasure editing this! Thanks for the insightful piece!

I remember this movie it gave me nightmares

Repulsion challenges viewers to confront the often invisible struggles of mental illness, especially when masked by societal ideals of beauty. It prompts reflection on how external appearances can deceive, leading to neglect of genuine psychological distress. In today’s context, the film serves as a stark reminder of the importance of looking beyond the surface to acknowledge and address mental health issues with empathy and understanding. But is there more to it??