Satoshi Kon’s Otaku: The Dangers of Technological Fantasy

The word “otaku” has defined how we think about the fan, at least here in the United States. However, this term is not always used to endearing; it carries a much different connotation in Japan, where the word originates from. To American otaku, to be called an otaku can be seen a badge of pride; it shows dedication and love for an anime or manga. In Japan, however, it is anything but positive. Literally, the word translates to “house” but colloquially, it means a person so dedicated to an anime or manga that they won’t leave their home. According to author Patrick W. Gailbraith, “There is significant discord between the otaku imagined along with booming anime consumption in Japan and abroad and the otaku image born of decades of negative press and social anxiety” (226).

Critically-acclaimed director Satoshi Kon especially touches upon this cultural topic of otaku in his animated films. Kon has said,

“In Japan not just children but adults in their 20s and 30s will choose anime and manga as a means of escape from their real lives. But I think there is a danger too. If you go into that world, it is very vivid and colorful and seductive, but there are big traps within that, particularly if you let your real world deteriorate as a result” (Kehr, 20).

But the otaku in his films aren’t always fixated on anime or manga; they are obsessive fans of anything from pop stars and actresses to even pieces of technology. According to Kerin Ogg, “Virtually no hobby or area of interest apart from film going seems to get Kon’s implied stamp of approval” (161).

Particularly, Kon associates his otaku characters with technology, which aids them in their obsessive tendencies and offers them a way to further themselves from a reality they do not wish to face. This technology can be anything from computers to video cameras. Satoshi Kon represents the otaku as a negative presence that becomes even more malicious, sometimes to the point of violence, when paired with technology. This idea is exemplified particularly in his works Perfect Blue, Paranoia Agent, and Paprika, with the exception of his film Millennium Actress, which represents what Kon sees as the perfect balance between fans and their use of technology.

Before addressing the films, it is important to analyze the overall aesthetic Kon creates for the otaku character. In all of the aforementioned films, the otaku character is not physically attractive, being either overweight, socially withdrawn, or both. An example would be Mima’s stalker in Perfect Blue, Me-Mania. He is described as “dead-faced and almost monstrous-looking” (Ortabasi, 283) as well as socially alienated, “painfully shy and socially inept” (Ortabasi, 283). He is not the only example in Kon’s films; there is Genya Tachibana in Millennium Actress, Kamei Masashi in Paranoia Agent, and Kosaku Tokita and Kei Himuro in Paprika. All of these characters are portrayed as overweight and socially withdrawn characters with their first priority being their particular hobby or object of interest. However, the image of the otaku does not just stop with physical characteristics; it extends to the living or working space.

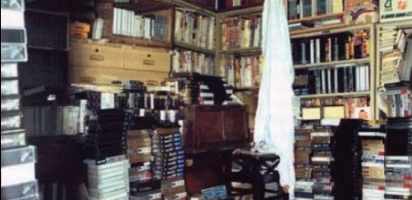

In all of Kon’s films, his otaku characters have extremely cluttered and dark living spaces with a flickering computer or television screen as the centerpiece that offers the most light. This image is well-known in Japan, as it is similar to photos of the room of Tsutomu Miyazaki, the first person to create a bad name for otaku when he murdered four young girls in the 1980s; many blame his obsession with anime and manga for these brutal crimes. The image of this room is one that is generally full of stacks of clutter, usually anime, manga, and pornography.

In Japan, it is easy for things to stack up due to the small amount of space in Japanese housing. However, the stacks in the home of otaku are not just stacks of everyday items, but stacks full of his or her specific hobby. According to Ortabasi, these images immediately make audiences aware of “a man who lets his hobbies stand in the way of human relationships.”

Perfect Blue

In Perfect Blue, Me-Mania’s apartment is packed full of images and posters of Cham and Mima. Masashi of Paranoia Agent is surrounded by the female dolls he loves so much; Tokita’s office in Paprika is cluttered, full of tools and plans to create new and better technologies; His office assistant, Hirumo’s, apartment is very similar to Tokita’s: full of cluttered shelves of pornography and anime as well as tools to create dolls he is known to love; Even in Millennium Actress, the film with a more positive otaku representation, Tachibana’s office is covered in scripts and videotapes stacked to the ceiling with his video monitors offering the only light. These images automatically define these characters as otaku before they even open their mouths.

A prime example of the relationship between fan and technology is Kon’s first, and most graphic, film Perfect Blue. The film addresses two levels of fan obsession, both of which are aided and magnified by technology. The first is the level of “the image of the fan community [as] a group of male nerds committed to the fantasy image of cute, young, and [high-spirited] girl singers” (Norris, 77). This is addressed particularly in film’s opening scenes as “male young men, who are bespectacled, too fat, or too thin… waiting nervously, cameras in hand” (Norris, 77) for the pop group, Cham, to come on stage. In particular, there are three nameless older males who throughout the film constantly scrutinize Mima, lead singer of Cham, as she has decided to branch out and become an actress. As the girls come onstage to perform, they are met not only by their male fans, but also the fans’ cameras. These cameras act as tools to strengthen the male gaze of these otaku who want to capture this image of Cham forever.

The idea of the camera plays a huge role throughout the film, especially as Mima begins to get in front of one for her budding acting career. In particular, she participates in a television scene where multiple men act out raping her character on the show, a stripper whose audience becomes too rowdy. This scene marks a drastic change from her image of an innocent pop singer, which is what she wants; she no longer wants to be seen as an innocent girl. Instead, she wants to be taken seriously as an actress. The camera, operated by all men, captures this moment of extreme vulnerability that is distributed among her male fans through the extremely public medium of television. The camera empowers her male fans throughout the film, giving them indirect power over her as their opinions make her feel vulnerable to their gaze.

Throughout the film, Mima worries about the opinions of her fans, hoping they will love her and follow her career no matter what she decides to do. Their opinions about Mima’s move to acting is reflected by the group of three unnamed otaku who discuss her career’s transition. While she is not directly told these critiques and judgments, she is constantly susceptible to their thoughts and opinions.

But the more malicious representation of the fan in this film is Me-Mania, Mima’s “number one fan” and stalker; he wants her to abandon all desires to become an actress and return to Cham. His obsession is not Mima herself, but an idealized fantasy of Mima who is forever a pop singer. His obsessive and destructive behaviors are amplified with his use of the Internet, which he uses to break down Mima’s mental state in attempts to get her to rejoin Cham. At the time this film was released in 1997, the Internet was a relatively new idea. In the film, Mima does not know what a webpage is, particularly when a fan yells to her, “I’m always looking in Mima’s Room.” Upon further investigation, she discovers that Me-Mania has established a webpage called “Mima’s Room,” where her every move each day is documented as if she has written it herself. This evolves from the innocent ravings of a fan to “the intrusion of the stranger’s gaze into the private realm of Mima’s real-life apartment” (Gardner, 56).

The power of the Internet gives power to the otaku character Me-Mania to “enact an imaginary usurpation where he has mastery over and possession of Mima and can rewrite her life, according to his fantasies” (Norris, 78). In an interview with Kon, he comments on viewing Mima in her private space and how “we also shot Mima’s room as if it was being viewed on a TV screen. This is because we wanted to give a diluted sense of reality, as if all of the events were taking place within a TV screen of some kind” (Kon, 1998). Kon creates a private space that is no longer private; people are always looking in, even if it is the film audience; a camera is constantly invading Mima’s private home space. Me-Mania believes his invasion of her home is for the greater good as “true Mima” visits him and urges him forward.

Even worse than Me-Mania is Rumi, Mima’s agent, who “represents a much more dangerous cross-identification with Mima” (Norris, 79). Rumi was once a pop star but her career did not last so she lives vicariously through Mima. In fact, she becomes a second Mima, “appropriat[ing] Mima’s identity as her own” (Norris, 79) and manipulating Me-Mania to do her bidding to “save” Mima from the acting world. She uses the social outcast Me-Mania and his knowledge of the technological world to invade Mima’s private space and attempt to show their love for her. Both Rumi and Me-Mania represent the epitome of “fan identity as a neurotic sickness” (Norris, 79) that instigates a moral panic towards the idea of otaku; their use of technology throughout the film only aids in this image as well as develops their “neurotic sickness” and obsessive fan identities.

Paprika

“The intermingling of daily life with dream, memory, hallucination, psychosis, cinema, and the Internet reaches new heights” (Mes, 2007) in Kon’s most recent film, Paprika. In Paprika, a seemingly uptight doctor, Dr. Tokita, becomes the lively Paprika in the dream world of the DC Mini, a powerful piece of technology that allows access to people’s dreams. This film depicts the potential dangers of technology, particularly as the use of the DC Mini begins blurring reality with the dream world. Many would say otaku actively do this as “they use entertainment and hobbies as a way of escaping real-world problems; they shirk their responsibilities and drop out of the community” (Ogg, 169). While Paprika is seen as an homage to international live-action film history, the film still has distinct otaku characters and provides a commentary about the dangers of fantasy.

Kei Himuro, Dr. Tokita’s lab assistant, is one of them though he plays a relatively minor role. His well-known love of dolls and withdrawn behavior causes his coworkers to suspect him in stealing the DC Mini. His strange tendencies concerning these dolls are connected in the dream world where he in fact becomes one of these dolls; technology unites Himuro with his obsession. While his strange behavior leads to his suspicion, he is in fact simply a puppet in the plot. But, his depiction as the stereotypical otaku is important as technology furthers his obsession, making him one with his favorite thing.

The other otaku in Paprika plays a much larger role in the film but is a different kind of otaku: his obsession is technology as he created the DC Mini. Dr. Tokita is a heavy-set yet extremely intelligent man who is constantly described as “child-like” for not understanding the deeper implications of the creation of such technology. Coworkers constantly berate him for his size and his maturity level, even though he is very obviously an adult. His actions are best summed up by his coworker, Dr. Chiba Atsuko:

“You get preoccupied with what you want to do, and ignore what you have to do. Don’t you understand that your irresponsibility cost lives? Of course not. Nothing can get through all that fat. … If you want to be the king of geeks (otaku no ōsama) with your bloated ego, then just keep up all this and indulge in your freakish masturbation!”

He is only seen as the man behind the construction of the technology who does not understand its limits. His actions have further implications when he ends up in the dream world because of his invention.

Both of these characters eventually are absorbed into the dream world of the DC Mini where they embody their real world obsessions. Himuro becomes one of his treasured dolls while Tokita becomes a giant robot, the embodiment of his love and disregard of the consequences of technology. These men are contrasted against Dr. Chiba/Paprika, a fan of live-action films who is depicted as a much more levelheaded fan. She does not fall victim to or lets the technology take over her life; instead, she appreciates the art form, as Kon does, but understands they are in separate spheres.

As Tokita and Himuro are the technology, anime-obsessed, overweight, messy otaku, Chiba/Paprika is “a more flattering (self-) portrait of the cinephile…clever, vivacious, physically attractive, and charming” (Ogg, 162). Kon uses Paprika to not only show the dangers of new technologies, but to also create two images of the fan with Tokita and Himuro contrasted against Chiba/Paprika.

Paranoia Agent

Then, there is Kon’s only television series, Paranoia Agent, which does not revolve on a singular otaku antagonist. However, it does have two distinct stereotypical otaku characters, Kamei Masashi and Kozuka Makoto, who play minor roles throughout the show. “The stereotypically overweight, bespectacled” (Ogg, 160) Masashi is the most obvious and stereotypical otaku. His apartment is full of bishojo, or beautiful girl, figures, which he creates himself, his front porch is covered in garbage, and the only organized portion of his home is his doll collection.

In short, his only care is his dolls, even thanking them post-orgasm for giving him the strength and ability to do so, while completely disregarding the woman in his bed. However, he is a relatively harmless character, as his love for dolls is not aided by technology. While his dolls absorb all of his time and energy, he is not violent or considered a threat.

The other otaku character, however, is seen as more dangerous due to his delusion that he is a video game character, “The Holy Warrior.” Middle school-aged boy Kozuka Makoto commits crimes similar to Shonen Bat, a boy on roller skates who is assaulting citizens with a baseball bat. Makoto “perceive[s] his violent assaults as one more level in his favorite game” (Ogg, 163) and does not understand why he is pulled in for police questioning; he simply thinks he is on his way to defeat the game’s boss level. His depiction as a “video game freak” (Ogg, 163) who participates in extremely violent crimes makes him another otaku character whose obsessive and violent tendencies are amplified by pieces of technology.

He is similar to Me-Mania in a way, as technology pushes them to the point of violence: the Internet pushes Me-Mania’s love of Mima to the point of violence while video games create a whole new reality of Makoto, causing him to kill or cause major injury. Kon creates two different kinds of otaku with these characters: one that is physically stereotypical yet harmless and another that seems normal on the outside but is actually delusional to the point of violence. These contrasting characters illustrate the point that almost anybody can be an otaku.

Kon’s point is emphasized even further as the show’s main otaku is the entire population of Japan with their obsession with technology and mass consumption. He makes this clear in the show’s opening shots of people on their cell phones, texting, or listening to music on various MP3 players. They have become “otaku manqué—obsessive ‘fans’ of media products without the attendant specialized knowledge of them or active engagement in them” (Figal, 140). As stated by Gerald Figal, “in their [Tokyoites] hypermediated daily lives and in their mania over a media consumable, they become unwitting and incomplete otaku without even knowing it” (140). In the world of Paranoia Agent, there is no longer face-to-face communication and personal relationships are dwindling, reducing people to individual balls of stress and anxiety with no outlet; “people must struggle for the ‘real’ without help” (Osmond, 91). Their anxieties manifest as the figure, Shonen Bat, who is attacking citizens throughout Tokyo with no motive, or so they think.

On top of this technological obsession, there is also a societal obsession of both adults and children with the pink droopy cartoon dog, Maromi — the Paranoia Agent equivalent of a Hello Kitty figure. There are dolls, t-shirts, vending machines, and even a TV show dedicated to this kawaii character. He, along with Shonen Bat, becomes society’s focus as they are both shaped into media sensations. As everyone sports a Maromi t-shirt, they also gossip about Shonen Bat’s latest victims, and how they know someone who knows someone who was attacked.

This obsession with both characters climaxes with a black ooze that destroys the city; this ooze “physically and metaphorically envelops and consumes media and consumers,” (Figal, 150) representing their own destructive, obsessive tendencies. Even more, the first victim of this ooze is the previously mentioned otaku Masashi as he finishes his final creation: a doll of himself wearing a Maromi t-shirt. This image “enacts the narcissism at the core of the media-consumerism nexus Kon explores… [and] suggests the negative self-absorption that shallow consumer culture can create” (Figal, 150).

Kon’s commentary on technological obsession does not stop with Tokyo’s initial destruction. Even when the series jumps ahead two years after the incident, nothing has changed; everyone is back to their normal routine of absorption in their technological devices. They even have a new kawaii creature to love in place of Maromi: Konya the cat. Kon uses this ending and this series as a whole to create a new perspective of the otaku, making it more relatable than just using one overweight social outcast.

He wants to show his audience how society itself has become a type of otaku with its love and dedication to various technologies; society has become a group of isolated individuals who can only interact through cell phones and the Internet. Kon creates a destructive relationship between society as otaku and technology to create a commentary on the damaging effects of the never-ending cycle that comes from combining obsession with mass consumption of technology and media.

Millennium Actress

Then, there is Kon’s film that reacts more positively to the fan: Millennium Actress with film director Genya Tachibana as the otaku character. The difference between Tachibana and all the other previously mentioned otaku characters is his preoccupation with live-action films, particularly those featuring famous film star Chiyoko Fujiwara. At first, his “positive qualities and his creativity are not immediately clear” (Ortabasi, 284), as his office space is that of a typical otaku character: cluttered and centered on a video screen displaying Chiyoko’s face, which is a “suggestion of quiet madness” (Ortabasi, 284). His collection of her films would mark him as a “typical idol otaku, who expresses his worship through fanatic consumption…[and] the only way to possess his idol is to capture her on film himself,” (Ortabasi, 284) which would liken Tachibana to Me-Mania in Perfect Blue.

However, the difference is Tachibana’s obsession is grounded in reality as “Kon’s cinephiles never (or rarely) let the real world sink below the horizon of their interests” (Ogg, 169-170). He understands the limits and remains grounded in the real world without fully losing himself to his obsession. This is based on one of Kon’s own “obvious interest in and fondness for live-action cinema [that] pervades [his] entire body of work” (Ogg, 158).

Tachibana has a deep love for the aging film star Chiyoko, and decides to make a documentary about her for his film studio, but really it is for his own personal benefit. So, this otaku uses technology in the form of a camera to further his obsession, but not in a destructive or harmful way like in previous films. In fact, Chiyoko is empowered by the camera and not sexualized in any way– the opposite of Mima in Perfect Blue.

In fact, Kon meant Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress to be sister films, with Actress having the positive spin upon the representation of the fan and “a model of cultural awareness and preservation” (Ortabasi, 283). Tachibana’s camera aids Chiyoko, encouraging her to tell her stories without attempting to induce any emotional trauma. Tachibana only wants to protect Chiyoko both emotionally and physically as he takes care to not upset her while also shielding her for falling debris during an earthquake.

He even manifests himself into each film scene Chiyoko relives, acting as her “knight in shining armor” in each scenario, her male savior. While this can be seen as Tachibana losing himself in the fantasy, he is with Chiyoko He is not just a fan of her work; he is in love with her or at least an idealized image of her from the past. He “is obsessed with a movie ideal of womanhood, manufactured for mass consumption,” (Osmond, 57).

Overall, Kon’s body of work reflects a negative attitude towards otaku culture and an even worse attitude towards the ever-growing dangers of obsession and absorption with technology. While Kon seems to be wary of the otaku he does not see them as harmful until they are paired with technological devices. He combines these two aspects of Japanese culture to create a societal message about the nature of obsession and how technology sharply increases these obsessive tendencies.

However, he uses the character Tachibana to create an antithesis, showing that there can be healthy fans. Kon is quoted as saying “the internet is a kind of mirror that reflects everything good and bad in society” (Kon, 2006). He believes that both the good and the bad exist through technology but there is a very fine line that is easily crossed by those dedicated fans. His films create a critique of his own medium, establishing that the world of animation is so outside of reality that it causes its fans to leave reality as well. Even when his characters are not necessarily fans of anime or manga, they are fans of something that has taken them from the world of reality and pushed them into a realm of sick fantasy.

Kon creates his otaku characters to show audiences that anyone can be an otaku, especially in this age of technology. Ultimately, Kon’s message to his audience is to “feel free to follow your passions—just do not lose yourself, and do not shut out the real world” (Ogg, 170).

Works Cited

Figal, Gerald. “Monstrous Media and Delusional Consumption in Kon Satoshi’s Paranoia Agent.” Mechademia. 5. (2010): n. page. Web. 10 Apr 2013.

Galbraith, Patrick W. “Akihabara: Conditioning a Public ‘Otaku’ Image.” Mechademia. 5. (2010): n. page. Web. 10 Apr 2013.

Gardner, William O. “The Cyber Sublime and The Virtual Mirror: Information and Media in the Works of Oshii.” Canadian Journal of Film Studies. 18.1 (2009): 44-70. Web. 9 Apr 2013.

Kehr, Dave. “Anime Dreams, Transformed Into Nightmares.” New York Times 20 May 2007: 20. Academic Search Complete. Web. 30 Apr. 2013

Kon, Satoshi, dir. Millennium Actress. The Klockworx Co., Ltd, 2001. Film.

Kon, Satoshi, dir. Paprika. Sony Pictures Entertainment, 2006. Film.

Kon, Satoshi, dir. Paranoia Agent. Adult Swim: 2004. Television.

Kon, Satoshi, dir. Perfect Blue. Rex Entertainment, 1997. Film.

Kon, Satoshi. Interview by Jason Gray. “Satoshi Kon.” Midnight Eye: Vision of Japanese Cinema. 20 November 2006. 20 Nov 2006. Web. 11 Apr 2013.

Kon, Satoshi. “Interview with Satoshi Kon, Director of Perfect Blue.” Apaki. . 04 September 1998. Web. 11 Apr 2013.

Mes, Tom. “Requiem For A Dream: The Films Of Satoshi Kon Bring The Depths Of The Subconscious Into Bright Anime Light.” Film Comment 43.2 (2007): 46-48. Academic Search Complete. Web. 29 Apr. 2013.

Norris, Craig. “Perfect Blue and the negative representation of fans.” Journal of Japanese & Korean Cinema. 4.1 (2012): n. page. Web. 9 Apr 2013.

Ogg, Kerin. “Lucid Dreams, False Awakenings: Figures of the Fan in Kon Satoshi.” Mechademia. 5. (2010): n. page. Web. 10 Apr 2013.

Ortabasi, Melek. “National History as Otaku Fantasty.” Trans. Array Japanese Visual Culture. Mark W. MacWilliams. 1st ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2008. Print.

Osmond, Andrew. Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2009. Print.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Satoshi Kon is a master in his field. He deals with all different subjects and all of his movies are engaging and beautiful in my opinion. And his series Paranoia Agent is stunning. I love Miyazaki also but at times I believe that Satoshi Kon is more innovative with his films.

I don’t watch much Anime but I’m Drawn to Satoshi’s subject matter and the surreal way he presents it all.

It really stays with you and seems to cross Film/Animation Boundaries

Exactly i wish i could talk about his films without sounding like an anime nut.

Intriguing study on his work. I love all of his films, especially Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress!!

GREAT post! I love both Kon and Miyazaki. Although Miyazaki is an acclaimed director, and even though i really love his films, there is something about Satoshi Kon which just instantly draws me in and never lets me go. Whereas with some Miyazaki films i have been known to get slightly bored with, I’ve never seen anything by Satoshi Kon where i haven’t been amazed in some way or another. His storytelling style is certainly superior to Miyzaki if you ask me, as well as his ability to blend reality with some form of escapism (Usually films, dreams and delusions).

The anime bit doesn’t matter – he’s a great director full stop! One of my all time favourites and has never made a bad film!

Millenium Actress is a masterpiece. If it wasn’t a anime, but a american live-action, people would be talking about it in the same breath as Citizen Kane…

I’m not sure, part of Millenuim Actress’s brilliance comes from the japanese culture within the film, and references to japanese cinema (especially Kurosawa’s works)

In Spain I find difficult that people liked his movies. The young ones, or otakus, would find his movies a bit uncommon (no science fiction, or unconventional one, strangeness, lack of defined hero roles…). The older ones despise everything that smells “anime” (or unrealistic, like they would say). Kon’s films fall in the middle, which is where a truly great director, in my humble opinion, should be.

Paranoia agent is one of the best films/series I have seen in all my life, anime or not, a masterpiece. Millenium actress is one of my favorite films, too. I think that he’s one of the best, and maybe that’s the reason behind his lack of popularity.

Janus is right on the money. And I notice a bad trend on the net. Miyazaki’s films are schlock compared to Kon’s and it’s time to retire the comparison — Kon is in a league with Kubrick, Rivette, Luis Bunuel, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Seijun Suzuki and Martin Scorsese. I’ve been following Kon’s films and career ever since I saw Perfect Blue in 1999, even driving halfway across California to see Tokyo Godfathers early. I was in the presence of the man himself at the L.A. premiere of Millenium Actress and felt that I was in the presence of an ancient wise man in the body of a Japanese matermind. Perfect Blue and Paranoia Agent are disturbing and alienating films that almost serve as Gnostic scripture, helping you build your strength to face life’s nastiness, while MA and TG are where Kon spreads the love. Kon makes films for nobody and that this is the sign of his integrity — my mom, who would have loved Millenium Actress if it were live-action, simply could not bring herself to connect emotionally with a cartoon.

Making anime with themes more mature than 99% of what passes for “real cinema” and thereby guaranteeing that he is ignored and misunderstood is part of the humility that is Kon’s most essential trait. Kon has not put a single untruthful moment on the screen. Not one frame. RIP.

Comparing Kon to Kubrick is a joke. Perfect Blue is terrible and PA only succeeds because it’s somewhat disjointed. Frankly, Kon is more of a Tarantino than a Scorsese.

after seeing perfect blue and the anime series paranoia agent i have only this to say: this guy is a fukin´ genious!! havent seen millenium actress or godfathers yet but wont be long now.

I adore Satoshi Kon’s anime. It was seeing Perfect Blue that really got me hooked on anime, it was the second anime I saw and I wanted to see more like it. His work is brilliant! I don’t know anyone who’s seen his anime except two people. One of them hates anything he does because he doesn’t like the animation and the other thinks he’s good. You rarely see his work being discussed to this level, great job. Instead everyone raves on about GITS and Miyazaki.

I just finished watching Paranoia Agent, the first work of his I’ve ever seen. Consider me an instant fan. Paranoia Agent is a masterpiece, to say the least, and extremely revolutionary.

I use to think Evangelion was the best, but Paranoia Agent is the first step toward a better future in animation, period. If Paranoia Agent was an American film or series, it would have one 8 oscars or emmies and be inducted into the library of congress and all that other prestige. But I doubt Hollywood would finance the script in the first place.

I can’t even watch anime the same anymore.

Satoshi Kon’s work is generally not the kind of thing your average fanboy/girl wants to see. Either the subject matter is too bland for them (a bunch of homeless people and a baby) or confuses them (Paranoia Agent). They’d rather stick to thier Naruto.

Then we have the rest of the filmgoing public. Most have no interest in anime, especially the elitists. Most think it’s below them.

Satoshi Kon’s movies are excellent, but unfortunately, they have a very limited audience. So nobody knows him.

I can’t wait to see Paprika.

Paprika is awesome! Give it a try; it was actually my first Kon movie. Since then I’ve seen pretty much all his films – and the soundtrack of Paprika is simply incredible!

I don’t know what it is about him, but even I (a huge Kon fan) tend to put his work on the backburner of my mind. However, when I’m recommending anime to others I always come back to all of his work. Everything he has done is brilliant, and I can’t wait to see more of his. Not only is he a great story teller, but his artwork is beautiful as well. Don’t get wrong, I thoroughly enjoy the classic anime artwork, but I applaud Kon for pushing the envelope both in story and in art.

I’ve seen Perfect Blue, Tokyo Godfathers and Paranoia Agent. Perfect Blue was amazing and it’s maybe the best anime I’ve seen. I also loved Tokyo Godfathers but Paranoia Agent was a disappointment I think. I have really high expectations on Paprika and even higher on Millenium Actress.

Kon is a genius and one of my absolute anime heroes, right up there with mamoru oshii and miyazake. every one of his films are absolutely mind blowing.

his work is simply too subtle, complex, and adult in nature to be accepted by the mainstream audience…

I have seen Paprika and Paranoia Agent before, but never thought about them so in-depth before. As I read this post so many details of those works were suddenly becoming much more meaningful than before. Thanks for writing!

Perfect Blue is the best anime I’ve ever seen, which is a pity since it was the 2nd anime film I saw after Akira (which put me off anime for a long, long time). Unfortunately, the thrill of watching Perfect Blue has not been repeated by any other film. Millennium Actress is interesting but not captivating. Tokyo Godfathers was also an exercise in curiosity but no more.

Btw, Hayao Miyazaki pales in comparison. His films can’t decide if they are meant for kids (who will find it too scary) or for adults (who find it too childish).

Akira was the first I saw too so I understand. If you want to see a truly great and moving anime movie, which in my mind stacks up to and surpasses Perfect Blue… watch Grave of the Fireflies, man that movie made me cry.

yea watch Grave of the Fireflies if you haven’t yet, the most powerful anime i’ve ever seen 😉

I always hear more people talking about Miyazaki films than Kon’s, which isn’t to say that Miyazaki’s praise isn’t well deserved. It’s just that Satoshi Kon’s work just hits me more on a visceral level than any film of Miyazaki’s. I found Princess Mononoke (sp?) and Spirited Away to be delightful films but I feel like Paranoia Agent and Tokyo Godfathers are more than just anime, more than just films, or shows, they’re pieces of art. They’re in a whole ‘nother league. I don’t know if that makes any sense to anyone else but it does to me. It is a real shame he is so underrated.

The word “anime” scares people away. And that’s a shame ’cause not everything anime related is stupid. Like Satoshi has proven.

RIP 1963-2010 🙁

Satoshi Kon is the godfather of adult oriented and smart anime. He never waters himself down. Even Paprika that was aimed at a more western audience, wasn’t spoon fed like all of Miyazaki’s films.

A great loss.

There are only a handful of directors that I follow closely. Satoshi Kon is one of them. I own and cherish all of his work. Fans should re-watch Millennium Actress as a memento of the magic he brings to film-making. The film itself celebrates film, stories, and a fan’s connection to the films/characters.

It makes me so sad that he is no longer alive. I have loved each one of his theatrical movies and even his tv series Paranoia Agent. Tokyo Godfathers is my fav out of all four movies. I have been searching around for an anime director on his level and all I can find that I like is the man who directed Summer Wars and Wolf Chuldren. Kon was one of a kind director and will be sorely missed.

Paprika and Magnetic Rose are two of my favorites. Think about all that was left unwritten.

Thank you Satoshi Kon for your excellent films and the immense pleasure I had in watching them.

I’m sure his mind will live on, If not in his own body, then through the body of others, as I’m sure that a generation of filmmakers is\will be influenced by his work .

Satoshi Kon was one of my favourite directors and clearly one of the best minds working in the film and anime industries today. His movies were always entertaining, very original and beautifully told.

So happy to see this one published; will definitely watch Perfect Blue the first chance I get 🙂

Outstnading read! Magnetic Rose is one of my favorite pieces of anime EVER. I have loved all of his stuff.

A genius gone before his time.

He was a magnificent creator.

He was amazing at capturing emotion in his flawless movies. His style was one of a kind.

If you watch any interview with him you can see how much he loved his job and how dedicated he was to it. Of course, you could also tell that just by watching his movies. He was one of the best directors of the past decade and his passion wasn’t just for animation but for movies as a whole.

He made some of the best anime! All the anime coming out these days all seem the same, but his definitely stood out from the pack, with a few others!

good

Ever since I saw Perfect Blue, I always anticipated the next Satoshi Kon release.

Although I didn’t like Tokyo Godfathers and didn’t understand Paprika, I realise he was a cut above the rest.

He had an entire career’s worth ahead of him. This just makes his early death that much more bitter. If Miyazaki had died that young he would never have finished My Neighbour Totoro or the Nausicaa manga and not even started on Kiki’s Delivery Service, Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke, Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, Ponyo… it really puts it into perspective, now we will never know what incredible films he could have achieved if it wasn’t for this vicious cancer. For such a young man he had achieved an incredible amount in quite a short amount of time- all of his films and Paranoia Agent are stunning pieces of work.

I was impresed by Paprika and decided to watch most of his movies. I think Paranoia agent and Millennium actress were his bigger “hits”, while I found perfect blue a little raw, yet…

his movies were extremely disturbing but also full of romantic and passionated issues .

He was a true film author in the world of anime, maybe the greatest.

I’m wishing for a kickstarter to get “Dreaming Machine” finished animated and released.

From Japanamerica by Roland Kells: “In 1983, when Japan’s economy was well into its monumental rise, journalist Akio Nakamori wrote a serialized magazine story, “The Investigation of Otaku,” explaining the term to common readers. Japan’s manga-obsessed nerds and geeks, he wrote, address one another by the following term, “O-taku.” In the late 70s and 80s, when anime and manga fans in Japan were first meeting one another at domestic conventions, they bagan to recognize one another’s face, though they did not know each other by name. By way of greeting, they said, “o-taku,” roughly meaning “hey, you” though with the more formal, less casual intimations of the French second-person address, “vous.” In American English it would be more like, “Hello there, sir.”

Great article! I had never known the word “otaku” to encompass anything other than the obsessiveness over anything anime/manga related. I’ve never seen any of Kon’s works, but I am greatly looking forward to seeing them. I greatly enjoy animes that get more in depth with their subject matter, like the show I recently encountered called “Steins Gate” which also touches on the subject of otakus in connection with technology. I love the connections you made and will be watching some of Kon’s work in the future because of this article!

What an interesting analysis on a great director.

Paranioa Agent is easily one of the best pieces of animation I’ve ever seen. The dangers of fandom and technology are but one of the many ideas of Japanese culture explored by Kon’s work.

Great article. I’m planning on writing a directed studies paper using Paranoia Agent as a case study to examine Jean Baudrillard and Slavoj Zizek’s critiques of modern-day technological society and it was great seeing such a well cited article. This helped a lot! Thanks.

VERY well put! I never put much thought into is use of clutter. This is used heavily in his short “Good Morning”.

Ah, I can’t wait to dive into more of his work. Paprika is one of my favourites, and that soundtrack is spectacular! I want more!

Satoshi Kon definitely was on to something when he spoke of “escapism”. Too much of a good thing, no matter what, can always lead to harm and he knew that it was fine to enjoy the culture of manga, anime, J-Pop, etc. but the over-obsession and desire to escape real life is where the bad came from. It’s the same with everything from “meatheads” (steroid abusers born of people who enjoy the gym) to “shopaholics” (people unable to stop spending because it gets them away from home and real problems). There’s all sorts of negative stereotypes with fun, innocent activities like watching anime, but of course the headlines go out to the ones who take it to the extremes. It’s a warning of watching yourself and ensuring you don’t forget to live the life that let you enjoy all these interests in the first place. Satoshi’s warning is to not let a good love for something become an obsession and remember there’s a far bigger world outside of one or a few strong pursuits that bring instance pleasure.

This is an amazing article, you described Satoshi Kon’s works to a tee. The way he portrays the world and how technology has such a large effect on us is always interesting to see. It is sad to see that he has left us and that we may never see his original vision for Dreaming Machine, or in some other form. Great article keep up the great work.

Interesting article you have here describing how Satoshi Kon’s films are a social commentary warning Japanese society about the dangers of otakudom and obsessiveness. I never thought of them that way.

Thank you for this well written and informative article. I’ve been interested in Satoshi Kon’s films since I saw ‘Perfect Blue’ a few years ago, which was certainly a strong influence for Darren Aronofsky’s ‘Black Swan’ (starring Natalie Portman). Putting that aside, I think Kon’s work has been largely undervalued in the West because he chose to make anime films and not live action. We still seem to have this impression in the West (among non anime viewers) that anime is orientated towards children or teenagers, so it’s difficult to educate others to understand that anime can handle serious issues just as competently as live action films. Satoshi’s exploration of the Otaku phenomenon does tend to over emphasise the negative aspects, but with good reason and ‘Paprika’ is a fine example of that. ‘Millenium Actress’ was for me a compelling piece and one I’ve recommended to several friends who wouldn’t normally watch anything with the ‘anime’ tag attached to it. It’s a such a shame that Satoshi died so young, but his work will live on and no doubt inspire new and upcoming directors.

I agree that if consumed in such amounts that it impedes your “real” day-to-day life, it can be harmful. But I think that applies to many things outside of anime and technology. I understand Mr. Kon’s concern, but I would argue that many people ‘escape’ from reality more entirely and impede themselves more on things entirely unrelated to anime than the majority of otakus, even in Japan. Anyways, great write up and I appreciate the additional perspective on Otaku life.

I haven’t seen any of these films, but I plan to watch them after reading these articles. Great Job.

Kon focuses on a specific type of otaku, one that is extreme and allows his obsession to hinder his day to day life. Many people who consume anime and the like would say they are otakus but none go to such lengths as Satoshi Kon’s characters. The way he shows how fanatic people can get with what they truly enjoy is interesting and that is why we enjoy his films.