Swinging Los Angeles: L.A.’s Forgotten Role as a Psychedelic Rock Mecca

The counterculture of the late 1960s was remarkably eclectic. What enabled this groundbreaking, multi-pronged movement to entrance the nation from Greenwich Village to Haight-Ashbury was the surprising intersectionality among its disparate strands, ranging from civil rights and second-wave feminism to anti-war activism. Above all, these pressing social concerns and fiery protests were accompanied by one of the most astoundingly rich soundtracks in modern history.

Contemporary listeners may view the works of Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Motown et al to be overrated and overhyped. It is easy to surmise that baby boomers are simply viewing the past through rose-tinted glasses. However, it is clear that the 1960s was equally a decade of hummable, infectious bubblegum and socially conscious poetry, both of which miraculously reached wide audiences.

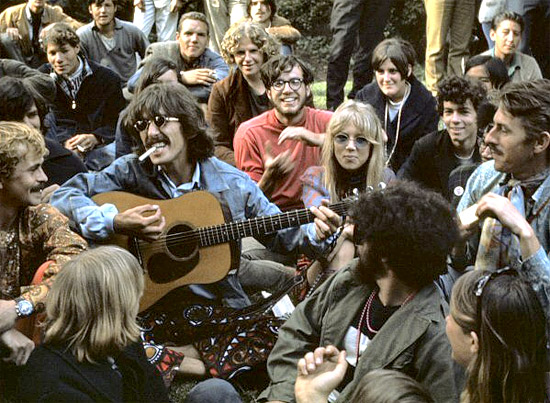

When choosing a single city to represent the American rock scene of the 1960s (which was primarily a response to the deluge of limey rock and roll dubbed “The British Invasion”), San Francisco inevitably is chosen as a microcosm of the musical trends of the Vietnam age. It is difficult to argue with the Bay Area’s dominance in this regard, as groups as instrumental and varied as The Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, Santana, Sly & The Family Stone, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Big Brother & The Holding Company hailed from the rootsy, quirky region. The area’s profound importance in the social history of the postwar period, including The Beats of North Beach and the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley, similarly cements the city as a zeitgeist capital.

Los Angeles, the sprawling, perpetually sunny city some 300 miles to the south, was regarded, as much as it still is in 2016, as a gaudy, synthetic pean to glitz and superficiality. When one thinks of Southern California and 1960s rock music, the peppy surf melodies of The Beach Boys and Jan and Dean come to mind immediately. The manufacturing of pop music, which would arguably hit its peak in the similarly warm-weather environs of Orlando, FL in the 1990s, found a home in mid-1960s Hollywood, as the pre-fab likes of The Association, The Turtles, and The Grass Roots entertained impressionable teenage listeners. The ultimate band-as-product, The Monkees, was similarly a Los Angeles creation, dreamed up by future filmmaker Bob Rafelson (Five Easy Pieces). The exuberant funk of Sly Stone, the impassioned wailing of Janis Joplin, and the long strange trip of that beloved pied piper Jerry Garcia were nowhere to be found in the shiny, smoggy Hollywood hills.

In reality, musical artists both popular (The Byrds, The Doors, The Mamas and The Papas) and highly influential (Tim Buckley, Love, Buffalo Springfield) hailed from the Greater Los Angeles scene, and helped to define the defiant eclecticism of the era’s popular music nearly as much as their Northern counterparts. Meanwhile, the legendary Laurel Canyon would attract musical migrants from Joni Mitchell to Graham Nash. By the 1970s, the musical atmosphere of the city had devolved into the monotonous strumming of The Eagles and their homogenized peers, but the L.A. of the 1960s was as musically adventurous and creatively fertile as Swinging London or The San Francisco Sound.

The Byrds and The Mamas & The Papas: Blending Folk and Rock, Pop and Psychedelia, in Incandescent Harmony

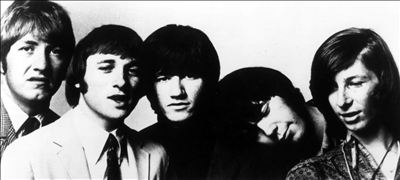

By 1965, the United States was at a loss on how to counteract the “British Invasion.” The Kinks, The Rolling Stones, The Animals, and most of all, The Beatles, dominated the airwaves, and it seemed that the only quality popular music was beaming across the pond. The protest folk of Bob Dylan and Joan Baez transfixed coffeehouses from Harvard Square to Larimer Square, but it failed to result in top ten success or radio airplay. In April of that year, right before a momentous summer which saw the release of the epochal singles “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” and “Like a Rolling Stone,” appeared the revelatory jingle-jangle of The Byrds’ “Mr. Tambourine Man.” The single completely and utterly transformed Dylan’s spacey acoustic original into a parade of chiming electricity, haunting melodies, and a groundbreaking mixture of folk, pop, and rock ‘n’ roll influences. This blending was labeled folk-rock, and hot on its heels were the equally innovative likes of The Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Do You Believe in Magic?” and Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Sounds of Silence.”

The Byrds were immediately hailed as the missing link between The Beatles and Bob Dylan, and for a brief but prolific run they were one of America’s most accomplished musical acts. This success, both artistic and commercial, was surprising, given the band’s scattered origins. Unlike the organic Liverpool roots of the Fab Four, L.A’s Byrds came from locales ranging from Chicago to small-town Missouri, and the group members were often hostile, competitive, and incompatible with each other’s personalities and musical aspirations. The gently nasal intonations and Richenbacher guitar of Jim “Roger” McGuinn defined the group as much as their plethora of great Dylan covers, from “My Back Pages” to “All I Really Want to Do.” Yet it was the timid Gene Clark who was their most accomplished songwriter, from hits such as “Eight Miles High” and “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” to underrated gems like “She Don’t Care About Time.” Meanwhile, the immense talent and ego alike of David Crosby fueled the group, pushing them into the melancholy of such bitter jewels as “Everybody’s Been Burned.”

The group reached peaks with the experimental albums Younger Than Yesterday and The Notorious Byrd Brothers, even though their last major hit single, “Turn, Turn, Turn,” was yet another cover and bowed in 1966, a year after their debut. In 1968, a year that saw the escalation of Vietnam, the murders of RFK and MLK, and the infamous “Chicago Seven,” the group splintered and re-formed, releasing the pioneering back-to-basics country-rock of The Sweetheart of The Rodeo. The album was completely out of step with the era, but its contradictory musical styles influenced the likes of The Eagles, Steve Earle, and Uncle Tupelo. On the whole, The Byrds may have not achieved the level of pop success of their influence The Beatles or California peers The Beach Boys, but their legacy shines on in groups ranging from Tom Petty and Big Star to R.E.M. and Wilco.

The Mamas & The Papas were akin to The Byrds in the jarring contrast between their harmonious musical seamlessness and clashing personalities. Unlike McGuinn and company, however, the dual-gendered outfit led to romantic intrigue and betrayal as well. Like the vast majority of Los Angelenos, the four iconic members of the Mamas & The Papas came from elsewhere. The group originally formed in the coffeehouses of New York, like many a folkie. Yet their bittersweet harmonies and sunshiny melodies were more in the vein of The Byrds or Beach Boys than Dave Van Ronk or Tim Hardin. The juxtaposition of the deep rumblings of leader John Phillips and soaring vocals of Denny Doherty, and interplay between the chipper Michelle Phillips and passionate Cass Elliott, led to a surprisingly original sound. Their classic debut album, If You Could Believe Your Eyes and Ears, was a key bridge between the carefree early ’60s and the dawn of the psychedelic age, spawning era-defining singles “Monday, Monday” and “California Dreamin.'”

The latter especially helped brand the Golden State as a magical land for seekers and wanderers, the young and the inquisitive. Just as drops of sorrow laced the seemingly upbeat melodies of their music, all was not well in the Mamas & the Papas. John and Michelle Phillips were married, but their matrimonial status did not prevent Denny from carrying on a torrid affair with Michelle. Meanwhile, tensions rose between the larger-than-life Mama Cass and the tyrannical boss “Papa John.” By 1967, the group were able to playfully satirize their image in the bouncy smash hit “Creeque Alley.” In June of that year, the Mamas and Papas, in tandem with mega-L.A. producer Lou Adler, put on Monterey Pop, a groundbreaking rock festival which saw the group share the stage with Los Angeles and San Francisco groups alike, as well as future legends like The Who, Otis Redding, and a fiery (literally) Jimi Hendrix. This event, like few others that season, helped define “the summer of love.”

However, to quote Tears For Fears, nothing ever lasts forever, and the group disbanded shortly after. Despite their short reign on the charts, the dysfunctional Mamas and Papas would prove influential. The then-anomalous use of twin-gendered harmonies would eventually spawn Fleetwood Mac and Abba, The Starland Vocal Band and The Magic Numbers, and “California Dreamin'” remains one of a handful of ’60s singles that virtually soundtrack the era.

It is ironic that two musical outfits known for their golden West Coast harmonies would have such a discordant existence, but this truth defined the era’s contradictions as much as it sums up the musical trends of this turbulent, experimental age.

Love and Buffalo Springfield: One Hit Apiece, Decades of Influence

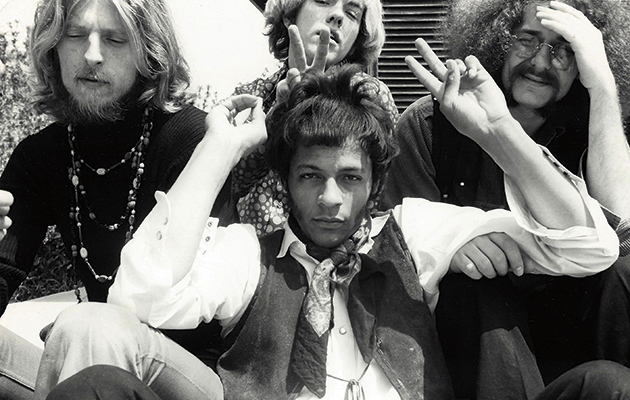

While the Byrds and Mamas & Papas were formed in the studio and Manhattan, respectively, a plethora of Los Angeles bands cut their teeth in the gritty clubs of The Sunset Strip, especially the fabled Whiskey-a Go-Go. The sweaty, vibrant nightclubs of this notorious Hollywood enclave were as central to L.A. in this era as Telegraph Avenue was to Berkeley. One of the first bands to stand out in this competitive subculture and land a record deal was Love, led by the brash Arthur Lee, a multi-talented singer-guitarist. A rare black frontman in the years before Hendrix or Sly Stone, Lee’s distinctive ensemble made a name for themselves as early as 1965, mixing garage rock and proto-psychedelia, and Burt Bacharach balladry with horn-laden pop. In fact, an early single was a radically re-worked version of the Bacharach chestnut “Little Red Book.”

It was 1967, however, when Love released two remarkably accomplished albums, Da Capo and Forever Changes. In an alternate universe, both LPs would have become hits as major as The Beatles‘ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band or Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow, but the group had to settle for cult success and a minor hit single in Da Capo‘s “Seven and Seven Is.” The follow-up effort, sneaking into stores at the tail end of 1967, struggled in the charts and was quickly forgotten.

With time, however, Forever Changes would be regarded as Love’s magnum opus, and one of the great achievements of this iconic period; it was ranked no. 40 on Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. An unclassifiable, inimitable stew of musical influences, all imbued with Lee’s commanding presence, inventive arrangements, and scorching guitar riffs, the album leaps out of the starting-gate with the one-two punch of the shimmering “Alone Again Or” (the single peaked at a mere #121) and the slow-building hard rock of “A House is Not a Motel.” Along the way, the pastoral “Old Man,” the frantic, insanely catchy “Bummer In The Summer,” and the show-stopping 7-minute closer “You Set The Scene,” make for an eclectic but cohesive album that stands the test of time. Effortlessly reflecting the exuberance and paranoia of a complex, much-hyped year, Arthur Lee & Co.’s masterwork is an indelible piece of L.A. Psychedelia.

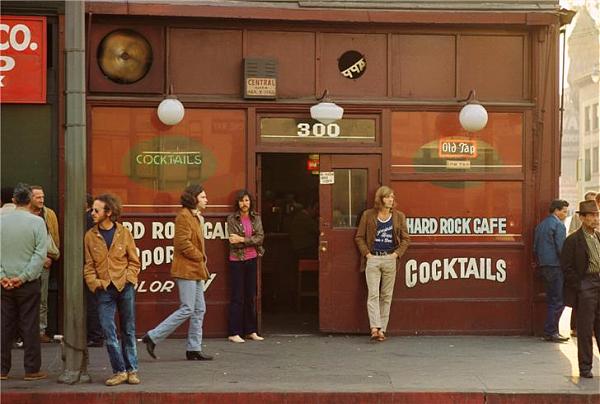

Unlike Love, the folk-rock ensemble Buffalo Springfield did indeed have a major, and lasting, hit song in “For What’s Worth.” A melodic but angry reportage on the infamous riots on The Sunset Strip, boasting the iconic refrain of “Stop, children, what’s that sound,” it is the L.A. scene’s equivalent to Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love” as a rallying cry and expression of the ethos of 1960s youth culture. Ultimately, however, the group has been pegged as a “one hit wonder,” and is today largely known as launching the careers of Stephen Stills (of Crosby, Stills, and Nash fame), Jim Messina (of Loggins & Messina), and most of all the legendary Neil Young. However, despite their brief three-album run and intra-band turmoil to rival The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield created some of the most distinctive-and best-music of the Los Angeles movement. Like the former outfit, Buffalo Springfield consisted of spare parts, rather than an organically formed, locally grown ensemble. Legend has it that Stills and Richie Furay, wandering L.A. musicians both, happened upon Young and fellow Canadian emigre Bruce Palmer on the side of the road on Sunset Boulevard, and an unorthodox assembly of musicians was born.

Regardless, the idiosyncratic band soon gelled on stage, and received a record deal with Atco in 1966. The first self-titled album contained such gems as “Sit Down, I Think I Love You” and “Nowadays, Clancy Can’t Even Sing,” but overall the folk-rock sound was enjoyable but fairly undistinguished. Their second album, boasting the expository title Buffalo Springfield Again, was a quantum leap in ambition, musical diversity, and song-craft. Stephen Stills still acted as the de-facto leader of the group, churning out rich, roaring tracks such as “Bluebird,” “Upside Down Boy,” and “Rock and Roll Woman.” Yet, notably, it was the first release where the idiosyncratic, innovative songwriting of Neil Young began to flourish. His “Mr. Soul” is as hard-driving a rock song as any of its era, but the majestic, quirky, and singular songs “Expecting to Fly” and “Broken Arrow” marked Young as no ordinary singer-songwriter.

Unfortunately, the excellence and eclecticism on display did not result in mainstream success, and on their last album, the prophetically titled “Last Time Around,” the group had re-arranged persona (including adding Messina) and released a muted, country-inflected set. Despite such gems as “On The Way Home,” “Kind Woman,” and “Questions,” it was clear that Buffalo Springfield was on its last legs. Just like The Byrds, the warring among such diverse talents as Stills, Young, and the underrated Furay led to an inevitably short shelf life. The band is not merely to be regarded as footnote in the career of Stills and Young, however, but as a key, irreplacable element of Los Angeles’ multi-faceted musical flowering.

The Doors and Tim Buckley: It’s Better To Burn Out Than Fade Away

Although the artists previously mentioned retain influence and mystique 50 years later, there are two musical acts from the fruitful Los Angeles scene that cast the most mythical shadow over the era, and ultimately transcend it. One was the most popular and controversial L.A. band of the 1960s, while the other was largely ignored in his lifetime. Today, however, both are considered legends of music who sadly perished before their time. The former is The Doors, who, then and now, are inextricably linked with their mercurial frontman Jim Morrison, while the latter is Tim Buckley, a “folkie” who eluded classification and gave birth to the cult indie singer Jeff Buckley. Outwardly, the two could not be any more dissimilar; a theatrical, driving rock band and a timid, tenor-voiced singer-songwriter. Yet, in each artist’s eclecticism, brief but prolific output, and mythically tragic circumstances, The Doors and Tim Buckley are kindred musical spirits. They likewise offer a glimpse into the promise, and sobering downfall, of the ’60s counterculture dream.

Akin to San Francisco’s Grateful Dead, The Doors are L.A.’s group whose appeal extends far beyond a nugget from a long-gone era, and today they remain one of rock music’s most cherished and idolized acts. Like almost all of the Los Angeles outfits of note, the group’s origins were scattered around the country, as an unorthodox mix of aspiring poets, filmmakers, and musicians converged on the sunny cultural mecca. The group’s four members- drummer John Densemore, guitarist Robby Krieger, and innovative organist Ray Manzarek among them- were all integral to the band’s unique sound, but Jim Morrison remains the face (and voice) of the immediately distinctive quartet. Along with his fellow “27 Club” members Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, Morrison’s alienated, deliciously dark musings made him a “voice of a generation,” just as the later club member Kurt Cobain would be for “Generation X.” His bravado, surging lyricism, and deep, droning vocals made him the archetypal rock frontman.

Akin to Love, a major musical influence, The Doors hustled mightily on the Sunset Strip circuit. They soon made a name for themselves as theatrical and ominous as they plugged in a lengthy residency at the aforementioned Whiskey a Go Go. Infamously, they were banned from the club when playing an early version of their Oedipal epic “The End,” as Morrison obscenely wailed incestuous lyrics. This was merely the beginning of a career of controversy and eventual arrests. After a solid year, The Doors’ self-titled debut was unleashed in the winter of 1967. The year was a goldmine of classic debuts, from The Velvet Underground & Nico and The Songs of Leonard Cohen to Hendrix’s Are You Experienced?

The Doors had by far the biggest commercial impact, as a “radio edit” of the sprawling, careening “Light My Fire” became a no. 1 hit, joining Scott McKenzie’s “If You’re Going to San Francisco,” and Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” as the zeitgeist anthems of the year. The rest of the album was varied and boldly original, bouncing from the fiery statement of purpose “Break On Through (To The Other Side”) and mysterious “Crystal Ship” to the giddy “Twentieth Century Fox” and rambunctious “Soul Kitchen.” Like many great artists, The Doors arguably peaked early, as their debut was their crowning achievement. As the years went on, and Morrison’s behavior grew more and more self-destructive, their legend only grew.

Despite the unevenness of their later work, such unimpeachable classics as “People Are Strange,” “Love Me Two Times,” “Five to One,” and “Touch Me” made the band one of the era’s pivotal acts. The latter part of their run was dominated by Morrison’s antics, most notoriously the alleged “indecent exposure” at a Miami concert in 1969. This is a shame, as their last two albums, Morrison Hotel and especially L.A. Woman were bluesy, raucous returns to form. The latter album’s “Riders On The Storm” is a single as epochal and image-defining as “Light My Fire.” The same year as The Doors’ triumphant comeback, Morrison was tragically found dead in a Paris bathtub. A decade later, Rolling Stone cheekily eulogized him as “hot, sexy, and dead,” and in the 2000s, Morrison’s face emblazons t-shirts from Tokyo to Mexico City.

In comparison to The Doors, Tim Buckley never became a mainstream star, and although his work is far more beloved today, he is still far from a household name. Hailing from conservative, white-bred Orange County, Buckley made a name for himself in the folk scene at the L.A. Troubadour, and initially worked with co-songwriter (and poet) Larry Beckett. The singer’s angelic voice and pure arrangements drew comparison to Phil Ochs, a Greenwich Village mainstay. However, Buckley, despite such tracks as “No Man Can Find The War,” was less overtly political, and as his career wore on, his style would become stunningly eclectic, far beyond the narrow confines of folk.

His first album boasted such tracks as “Wings” and “She,” which showed off his considerable vocal prowess, but the follow-up effort, 1967’s Goodbye and Hello, was yet another triumph that year from Los Angeles. From the intricate title track and haunting “Pleasant Street,” to the wistful “Once I Was” and incandescent “Morning Glory” (perhaps his signature tune), the album was eclectic and uniformly excellent. 1968’s Happy Sad boasted baroque arrangements and a stylistic consistency absent on the diverse preceding LP. Despite the quality of Buckley’s music, neither work made a dent on the Billboard charts.

By the 1970s, Buckley proved he was no California flower child by re-shaping his sound into spacey, sharp-edged funk on Starsailor and especially the image-re-defining Greetings from L.A. The songs ranged from the funky, erotic “Sweet Surrender” and “Make It Right Again” to the sprawling, jazz-inflected “Hong Kong Bar.” As the 1970s reached its mid-point, it was clear that Buckley’s time had passed, as he fell into substance abuse. In 1975, he seemed poised for a comeback, as acclaimed filmmaker Hal Ashby (Harold & Maude) wanted to cast him as folk pioneer Woody Guthrie in the biopic Bound For Glory. Tragically, he died of a fatal heroin overdose that year, and initially his death was reported to little fanfare. In subsequent years, his reputation grew, and today he is regarded as one of the most important and multi-faceted of singer-songwriters. He may not be as renowned as Jim Morrison, but akin to the “Lizard King,” he outlasted the era and location in which he came to prominence, emerging as one of music’s most beloved tragic heroes.

In the annals of “acid rock,” a genre that has been exhaustively written about and filmed, San Francisco and the surrounding towns of the picturesque Bay Area reigns supreme. In the public imagination, it was the Avalon Ballroom, Fillmore West, and Haight-Ashbury which served as the epicenter of the flower power age, not The Whiskey A Go Go, Troubadour, and The Sunset Strip. Gazing at the vast array of musicians who populated Greater L.A. reveals a city as musically important as its hipper Northern cousin. The subsequent decade may have led to the bland, slick stylings of The Eagles, Jackson Browne, and the re-branded Fleetwood Mac, but Los Angeles in the 1960s remains one of the most fruitful intersections of time and place in musical history.

Works Cited

Doggett, Peter. “There’s a Riot Goin’ On,” 2007.

Hodgkinson, Mike. “Following The L.A. Hippy Trail,” The Guardian, 2008.

Montagne, Renee. “Mayhem in Laurel Canyon,” NPR, 2006.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Love this music and it reminds me of when the world was a bit more magic.

It is very disconcerting that it is our generation — our icons — who have been dropping like flies recently. I remember watching the big figures of my parents’ generation as they one by one became very old and then . . . were gone. I tried to imagine how my parents felt about it. Now I know. To me if feels like signs and portents, a signal that it has really begun, and soon we will all be gone. Too bad for us.

It’s all perfectly natural and therefore good. There’d be no room on earth for all the people if we were immortal.

Excellent work on thoroughly analyzing various music artists. I wasn’t terribly familiar with ’60s L.A. or “acid rock,” so this taught me quite a lot.

People say the 60’s dream died towards the end if the decade, I think it’s dying now.

What a great write-up. I remember my big sisters playing some of these records a long time ago.

YouTubed some songs and heard the guitar psychedelic boogie of the year! GREAT!

Just remembered The Byrds are unbelievable. What a band.

Time to revive this genre.

I rarely hear people talking about these bands in my social circle. I will introduce their music to them. I was not alive in this era.

Jefferson Airplane is my favorite of this genre. After Bathing At Baxter is one of the greatest artistic achievements of the psychedelic era. It was the album that broke loose with the conventions of the song format and the pop arrangement.

Samuel, very well done. I appreciate your inclusivity of the variety of artists that were creating music and culture in that era.

This is my childhood.

Thanks very much for the article.

Boring old hippy stoner rock – not especially psychedelic.

I think psychedelia is often just an excuse for committing a lazy old jam session to CD. I guess I’m just not enough of a stoner.

I am really starting to dig stoner rock and Psychedelic rock.

Pink Floyd.

LA was the strand of psychedelic music.

I miss the psychedelic generation of the past.

Check out the book “Walk, Don’t Run.” It’s all about Edward James Olmos’s band in the ’60s. The book includes a soundtrack: his band’s album that they recorded. GREAT Music.

Amazon link: http://amzn.to/1CSwmDD

Interesting post. They all helped form psychedelic-rock as a musical genre.

Between 1963 and 1966, rock music was amazing.

Technically they came from Japan, but Flower Travellin’ Band fits right in with this scene. Great psychedlic stuff, I’d even say proto-metal. https://youtu.be/BxB55yaWG-I

Such an awesome niche topic.

No Seeds? C’mon. And this is about 1966 and thereabouts LA? Someone smokin’ something…

Music indeed unites people of all backgrounds together. Although messages sent may differ from the mid- 1900’s until today; we have come a long way since then.

Music unites people of all backgrounds together. Although messages sent maybe different from the mid- 1900’s until today; we have come a long way since then. The quality of the music videos and advertisement dramatically increased as well.

This post was really interesting to read about. This topic definitely could relate back to today as well because of the large music industry today in the L.A, and California area. Lot of this music people have heard of and can really have a understanding on as well.

This is very well written! I enjoyed reading about musicians I was already familiar with, but learning how many of them are linked to each other. Listening to your favorite artists’ influences is a great way to find new music. Thanks for making me wish I was living in California in the 60s!

This seems to encapsulate what would become Glamorous California in the 70s and 80s.