Television, Humour and Transnational Audiences

Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt went swimming in 1967 at a Melbourne beach and was never seen again. The Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Pool was built as a mark of ‘respect’ for this tragedy. Furthermore, when seven bodies were discovered in barrels in Snowtown, New South Wales, Australia in 1999, the town’s stores started selling coffee mugs with captions that read “Come to Snowtown, you’ll have a barrel of a time.” It can be seen that humour, while familiar and heartening to a particular group of people, may be misunderstood or disrespectful to others. This illustrates how humour is shaped through the context of culture. Humour is a form of communication understood by individuals that relate through shared behaviours, experiences and values. However, humour in television media can expose issues of being lost in translation through cross-cultural consumption, which is enabled by contemporary global media. This issue provides understanding of the significance and connotations within a certain national humour that may largely differentiate in how the message is portrayed and received by different audiences. This rationale is based on how the contextual meaning of a text resonates differently between transnational audiences.

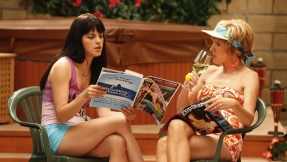

American and Australian humour demonstrates divergent interpretations of meaning and context. This clarifies a major issue in cross-cultural interaction through the globalisation of television texts. Australian written, produced and cast television series Kath & Kim is a national success that is appreciated by Australians for its use of niche, specific humour. The ABC series from 2002 focuses on the dysfunctions between a suburban mother and daughter. The humour is derived from local references, garish costuming and cringe-worthy mispronunciations to create a light-hearted parody in representation of the Australian lower middleclass. Those who “get it” see Kath & Kim as a triumph of an Australian joke in bad taste. This perspective sheds light on how the show’s social status-based humour effectively pinpoints the Australian embrace of self-ridicule. This is through the satirical treatment of cultural stereotypes and characterisation. Such representation allows the text to resonate successfully with Australian audiences. Ultimately, this resonance stems from their understanding of behavioural and social norms of their cultural identity, and when these norms are overstepped to create a humourous response.

Post-1980 marks the digital age of technology, the internet and globalisation, which has harnessed media circulation in the era of increasing global connectivity. Cross-cultural communication has enabled texts to enter the international market. While many prosper and expand, there is the potential of texts to not be so successful among audiences in another cultural context. Kath & Kim US did not translate the original features of irony and satire to American audiences that made the show successful in Australia. Kath & Kim US aired in America in 2008 and was soon cancelled after only airing 2 episodes, due to low ratings.

Kath & Kim US was adapted with an American cast, but flopped because the original humour of Australian local references meant offshore audiences didn’t quite understand the culturally specific content. The original “spunky ladies” of Fountain Lakes, Melbourne were adapted to wealthy Los Angeles, which lost all sense of the satirical references of middleclass suburbia. It is the social and cultural niche of ‘Aussie’ humour reflected in quotes, “crack open the Tia Maria” or a “barbie of commemorative sausages” that provoke a familiar cringe to Australian viewers. Further Australian slang phrases in Kath & Kim such as “manbags” (men’s satchels), “Maccas” (McDonald’s) or “the toot” (the toilet) add to the show’s humour of emphasising the social and cultural identity of the Australian language. However, the localised humour left Americans confused on the appeal and seriousness of such characters. The Australian characterisation of Kim’s “muffin top” and Kath Day-Knight’s “foxymoron” perm were further lost in translation, as the Americanised duo weren’t nearly as exaggerated enough to be absurd. It is the ridiculousness of the Australian characters that give them humorous appeal – but this facet was removed in the US version, in America’s struggle to understand irony as form of sarcastic humour, rather than rudeness. These points highlight the problems raised by cross-cultural consumption.

Kath & Kim US was adapted with an American cast, but flopped because the original humour of Australian local references meant offshore audiences didn’t quite understand the culturally specific content. The original “spunky ladies” of Fountain Lakes, Melbourne were adapted to wealthy Los Angeles, which lost all sense of the satirical references of middleclass suburbia. It is the social and cultural niche of ‘Aussie’ humour reflected in quotes, “crack open the Tia Maria” or a “barbie of commemorative sausages” that provoke a familiar cringe to Australian viewers. Further Australian slang phrases in Kath & Kim such as “manbags” (men’s satchels), “Maccas” (McDonald’s) or “the toot” (the toilet) add to the show’s humour of emphasising the social and cultural identity of the Australian language. However, the localised humour left Americans confused on the appeal and seriousness of such characters. The Australian characterisation of Kim’s “muffin top” and Kath Day-Knight’s “foxymoron” perm were further lost in translation, as the Americanised duo weren’t nearly as exaggerated enough to be absurd. It is the ridiculousness of the Australian characters that give them humorous appeal – but this facet was removed in the US version, in America’s struggle to understand irony as form of sarcastic humour, rather than rudeness. These points highlight the problems raised by cross-cultural consumption.

Australians celebrate and relate to Kath and Kim’s Australian-isms, often seen as an extension of themselves. As a born and bred Australian, I laugh along with these characters in their display of familiar values to our national identity. However, the US characters were translated as separate, almost distant, from American viewers. The content and characterisation didn’t reflect the social and cultural values that American audiences identify with, resulting in US viewers laughing at them and not with them. Kath & Kim is a key example demonstrating cross-cultural issues when texts globalise. This illustrates that the use of niche humour and local references in the text were crucial issues contributing to its demise amongst American audiences. Here, humour is emphasised as a social and cultural practice, which can be a problematic aspect of intercultural media translation.

Britain’s The Weakest Link is another text that explores how its importation to Hong Kong failed to communicate a contextual understanding though the use of humour. Its success in the UK was not reflected in its 2001 adaptation, 筆OUT消 (or The Weakest Disappears) for Chinese viewers. The show did not translate the cultural expectations in communication and behavioural norms that differ between the UK and China. This displays the problematic barriers to cross-cultural interaction when texts are adopted and adapted overseas. Issues of cross-cultural communication can be examined through factors of Geert Hofstede’s dimensional model of culture (1980). This successfully creates reliable, theoretical evidence to understand the differences in high and low context cultures that separate Eastern and Western cultures.

The UK quiz show’s host and contestant dynamic differs to other cash prize quiz shows. The Weakest Link centralises the host to be the pivotal feature to the show’s humour. The host is deliberately nasty to ridicule, mimic and belittle the contestants to create the fast paced atmosphere of competitiveness. The wit of irony in the UK version is the cut-throat honesty typical to sarcastic British humour. The Chinese version followed this exact format, but revealed to be conflicting to traditional communication of Chinese culture through assertiveness, nonverbal codes and humour.

This is explored in Hofstede’s theory of individualist and collectivist dimensions of culture. Individualism is seen in English communication as explicit messages pursuing personal concerns at the expense of other parties, reflecting a low context culture. This includes conflict, insults and immodesty, encouraged amongst the British The Weakest Link contestants for comedic value. Alternatively, collectivism, according to Hofstede, is seen in Chinese culture as the value of harmony and confrontation avoidance, attributed to their high context culture of conflict management. These opposing sociocultural values meant that Hong Kong’s The Weakest Link was watered down in tone, insult and the use of irony at others’ expense. For example, I’ve watched a British contestant vote off her peer in saying, “She came here I think totally believing she was going to win, but I actually think somebody deserves it a lot better”. In contrast, a Hong Kong contestant in the same situation said, “I think she was very nervous and so she should rest a little”. This broadly reflects Chinese culture through indirect criticism put down to nervousness rather than ability. This kinder approach in Hong Kong’s version differentiated to Britain’s harsh criticism and personal remarks for comedic value.

This supports how Chinese and British communication and humour diverge in terms of assertiveness, explicitness of messages and modesty, which result from an individual’s national identity. This creates an understanding of the issues surrounding the comprehension of imported content. The Weakest Link clarifies the problems of globalising television media that arise when texts are taken out of their original context and introduced to other cultural audiences.

This supports how Chinese and British communication and humour diverge in terms of assertiveness, explicitness of messages and modesty, which result from an individual’s national identity. This creates an understanding of the issues surrounding the comprehension of imported content. The Weakest Link clarifies the problems of globalising television media that arise when texts are taken out of their original context and introduced to other cultural audiences.

Cross-cultural interaction is constantly increasing and strengthening with the ease of accessibility and omnipresence of technological connections, enabled by contemporary global media. Television media content is created with the influence of social behavioural norms, cultural references, tradition, lifestyles and languages. Hence the consumption, comprehension and significance of international content to transnational audiences will pose problems when content is created in differing contexts. Humour is an extension of national identity, shaped by the cultural and social cues that differ from one culture to the next. Humour within television media is a niche creation of what is relatable and local to certain social and cultural groups. While cross-cultural connections are widening, content as examined in Kath & Kim and The Weakest Link may not always successfully enter the new offshore market with the same meaning and insight from new audiences. It can be concluded that issues in translation may not only apply to language dialect but furthermore, the translation of social and cultural codes that differentiate national identities from one another. These problems raised by this cross-cultural interaction aim to determine how the use of comedy is portrayed and received by transnational audiences.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

We tend to underestimate the ability of transnational viewers to comprehend and enjoy foreign humor. This underestimation is limiting our culture.

I agree, great insight there. Thank you.

This is a strong piece Michelle. Thanks for the read.

Thanks Ian for reading.

Humor normally involve content of high personal significance. If content creators can master a formula that is relatable for a transnational audience, the content will be received well by all.

Exactly, humour is derived from personal and cultural resonance which is proving difficult to capture on a broad playing field. Though in some cases, it works (The Office etc).

I’m an American and love British humor but comedy from US, not as much. What does this say abotu me?

That is very interesting haha! I love British humour, and Aussie humour seen in the approach of Kath & Kim, but other Australia humour is not for me – I can relate!

This is a very interesting article on a subject that I admittedly know very little about. I do think much humor is linked to cultural specificity and your article does a great job of highlighting the various ways this can manifest. I’m wondering if there is a way to remedy this?

Thanks Jon, I love delving into this kind of stuff. There must be a remedy, but I’m finding it hard to pinpoint. Many adaptions have worked, alongside the ones that have flopped – but I think the key to transnational production is research; it’s crucial!!! Often, money is the driving factor and I don’t think these creative teams do the extent of homework they should do to see if this adapted content is going to connect to new audiences.

Very good article.

The issue is really twofold. That all humor is contextual and that the people adapting a show from country A to country B rarely seem to be interested in what made it popular and successful in country A, they just see the potential for revenue generated and give it a try.

I couldn’t agree more. Thanks Taylor!

What about shows like Summer Heights High/Ja’mie that have a massive cult following in the US after being picked up with I’m assuming little to no changes? What do you think sets these shows apart from the less successful adaptations and syndications?

Summer Heights High and Ja’mie are complete hits, in America and even in the UK. Though, it hasn’t been adapted. Chris Lilley creates works that are adopted into other cultural contexts, and I don’t know how he does it. That is a good area to explore for a future article.

Great read!

Thank you! 🙂

I suppose it comes down to the indispensability of market research, like you said. The essence of marketing is to KNOW your market, and thus all these shows could not transcend cultural barriers as the producers/writers did not understand their audience. We just saw this recently with Blackberry, who is lagging behind the smartphone pack as they insisted full keyboards were more popular than touch screens. Convenient that I’m currently typing this on my touch Sammy?

So know know know your market, I can’t agree more!

Very well said, and agreed! Thanks Emily.

Make sure there are no cultural snags and address them before a copy-paste job.

I just wanted to throw in this interesting piece about German comedy written by Stewart Lee – http://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/may/23/germany.features11

Thumbs up Johnny, cheers!

This is a good look at international humor. I tend to not find foreign films funny. Even Monty Python. But some actors like Ricky Gervais get it.

An interesting take on the issue: http://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/feb/10/comedy.television

I think people often relish in their own niche humour since it forms a community and a circle of relation, however, so-called ‘outsiders’ of a collective’s humour can appreciate it for its very idiosyncrasies.The success of Gavin & Stacey throughout the UK demonstrates people’s appreciation and love of such humour.