The Beginner’s Guide: The Artist and The Audience

(Note: this article does include spoilers for the game. If you have not played it, I deeply suggest you do so before coming back to read the article.)

Some (if not all) of the world’s most fascinating creators have suffered from the horrid monster named ‘Creator’s Block’ one time or another. That devious creature that sneaks into your mind and drains you of all your creative energy, leaving you feeling hopeless and lacking self-worth. If you have ever suffered from this, you know that it is a physically and emotionally draining beast that can drive you crazy in search of some facet of creative energy. You would kill just to get a taste of that buzz you get from making something you know is important. To even more of this avail, it becomes worse when you know you must create for an audience that seems to be imposing on your every step, making it impossible to do anything without being commented on or otherwise contradicted. This is the case of Coda.

The Beginner’s Guide is an introspective video game by Davey Wreden, the creator of The Stanley Parable. The game focuses on the joys and problems that creators face, particularly when dealing with an audience and lack of creative inspiration. It questions the relationship between a creator and their audience, and the lines that should and should not be crossed between the two.

In the game, you play as a third-party viewer to the story. Your guide, Davey, is taking you through a series of levels built by his former friend Coda. Davey describes Coda as a very isolated person, and seems to create his levels primarily as a means of self-expression. Each level has a very unique spin to it, ranging from you walk past a sign for about ten seconds and that’s it, to a level about travelling up a giant stair case that forces you to slow when you get half way up. The end of most of these levels appears to show us something about the author. However, as we learn further on, looks can be deceiving.

As we continue, we discover more about Davey and Coda’s relationship. The two met at a game convention in 2009 where Davey immediately became a fan of Coda’s after seeing a level introduced as ‘This level is connected to the internet’, where Coda creates a series of messages around an open area virtual space, pretending as if each message was written by other people while. Davey’s relationship with Coda begins as rooted in their love for interesting and methodical level creations, but slowly over time becomes creatively toxic, if at least parasitic.

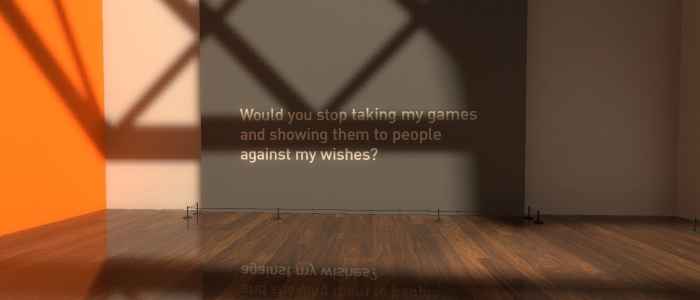

Near the end of the game, we see Coda’s games slowly become more and more desperate, speaking directly through his games as cries for help and his fears about having creator’s block. He creates games all around his need to create games, but his inability to create anything he thinks of as new or fulfilling. After a particularly horrifying series of levels, Davey decided to show off his friend’s levels to people to help develop a fan base – without Coda’s permission. To this end, Coda immediately denounces Davey and asks for Davey to never contact him again. After this, Davey immediately is riddled with guilt, trying to understand what he did wrong, not seeing his betrayal of Coda’s trust as a negative thing, but as a call to arms to try to bring inspiration for Coda through social gratification, something that Davey seemed to desire but not Coda. Davey ends the game with a final moment of self-reflection, before we are left to question everything we understood about Coda and/or Davey throughout the game.

When reviewing the relationship between Davey and Coda, it is not hard to draw insight on the relationships between any audience and an artist. Any fan knows the desire to understand a work so fully that they can understand the mindset of the people who make it. This is the case for Davey, who commonly talks about how he wants to understand the creator completely through their work, and not have to deal with the social parts. To many this idea is alluring; to know someone almost completely through a work of art brings a kind of calming intimacy. We all understand the concept that a creator puts a little piece of their soul into what they create, but to assume their being is ingrained within its walls is not only wrong, but quite destructive.

In its most basic terms for any audience to creator relationship is symbiotic. The creator develops a work of art that the audience creatively and intellectually feeds on. The audience will continue to enjoy and absorb a creator’s work, giving the creator means to exist creatively and economically through purchase of their work. This cycle continues until the audience is no longer focused on that creator. However, with the wrong kind of audience, this cycle can quickly turn to a parasitic one, which is what we see when looking at Coda and Davey.

Coda, being the creator, is being feed on by Davey, the parasite. Coda creates a work as he likes and Davey is there to feed. But, when Coda is unable to further produce for Davey by himself, Davey decides to find ways to force his host to give him more. Even further, we also begin to see Davey trying to inhabit the work of Coda. This goes beyond trying to find meaning in the work, and actually changing it so it is no longer the creator’s, but the audience’s work.

For example, at the beginning of the game, Coda’s works have no definitive endings. They merely exist, and it ends when the screen goes black. However, after many arguments between the Coda and Davey about having endings in games, Coda begins to place street lamps to signify the ending of his levels, even if he is not interested in doing so.

Then, in that case, does the work belong to Coda, or to Coda AND Davey? Coda created everything in the level, but Davey was the one who established the definitive ending. Does is belong to both of them? Does on the end belong to Davey, but the rest Coda?

And from that, based on their relationship, who is really in control? Is Coda in control of the work he creates, or is Davey the one who decides because he is the audience, and the creator’s job is only to create for their audience’s entertainment?

If that is not enough, consider this; if Coda and Davey are in such a close relationship together and requiring one another for survival creatively, what are the borders of their influence? If a creator has the rights to a work because they made it, and an audience has the rights to the work because they are the intended recipient of that work, does that mean that the creator and the audience have rights to each other?

In Davey’s eyes, he does have a right to Coda’s mind. He wants to understand how Coda thinks so he can understand what he creates further until he is able to understand Coda in his entirety as a human being.

To Coda, Davey has no right to be in his mind. Coda created these levels as a means of self-reflection, and having someone invade that space can be terrifying if they misunderstand or otherwise hate what they see. Therefore, his reaction is to retreat, making it difficult for others to see inside of him, but also making it difficult for him to understand his own feelings and emotions.

Many writers, actors, directors, artists, etc. have had numbers of people ask questions and make statements beyond the necessary limits of reality if they believed they knew someone entirely based on something that a person has created. Especially with the birth of the internet, these false ideas can rally groups of mobs to bombard creators, often leading to severe consequences, such as the creator giving up on a craft, otherwise disappearing from society, to even mental illness and suicide.

While there always small pieces of artist in their work, a person can never assume how they read a line of text to be the only and right way of doing so. A creator is never entirely within their work, neither is their work entirely their audience. While the artist’s job to create, it is only the job of the audience to interpret as they wish, knowing that they may look it from different perspectives. This is why two people can look at a single work and see two separate things. This is why Davey is allowed to have his perspective that the level’s should have endings. But, the imposition of Davey on Coda for him to have endings is where it went wrong. The constant stress Davey placed on Coda instead of the work itself inevitably caused Coda to crash and burn since he was no longer in control of what he was creating. He was creating under Davey’s boot because that is what Davey thought was best for Coda’s art, since Davey thought he understood Coda better that Coda knew himself just from playing the levels Coda created.

A piece of arts job is not to show you something in the world that is defined by morality, law or otherwise, but only to make you question what you see as defined and interpret its meaning for yourself. Davey should not have looked Coda’s work as something that is concretely ‘Coda’s Ideals’ but as creative way to explores ideals that Coda has put forth to question. An audience has the right to question, think and talk to the creator about their ideas and message, as well as choose the artists they listen to and otherwise enjoy. But, they have no right to infringe upon an author to force them to do as they wish unless the author is willing to do so in the first place. Otherwise, it will never really be art.

With this in mind, if you are a member of a creative audience, let Davey and I ask you this;

“So, if your role here is not to understand, then what is it?”

If you shouldn’t look deeper than the text for meaning, if you shouldn’t assume anything about an author, and you shouldn’t try to infringe on the work of an author, what is the purpose of the audience?

To think.

To question.

To learn.

To understand.

To support.

These are the only things you can do when you reflect on the work of your favorite artist. These are the things everyone has rights to as an audience to the creator, and to each other. These are the things that we as fellow artists, thinkers and collaborators should do for each other as a creative audience. These things promote different ideas and diversity within all creative mediums, allowing the creation of great things.

Otherwise, you may find yourself with many an artist who won’t respond to your critical YouTube comment.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

The fundamental question is flawed: anything someone creates gives insight into their mind. You just have to ask yourself why they created it. Even more than actions, creations last and thus they can be analysed in the way actions can’t, not being twisted by memory or time. (At least, in the abstract. Obviously things change or are destroyed.)

So I wonder then. Whose mind will we be looking into?

I wrote this game off the first 2 minutes of “gameplay” because it just looked like crap. But boy, was I wrong! Sure, there isn’t much gameplay in this “game”, but the narrative and level design, as well as in-game messages definitely gives one a different perspective and insight of what creatively is. I was really impress at what this game had to offer.

I know nothing about this topic, Nevertheless, loved your writing style, so it’s an enjoyable read, not to mention your insights into creativity. I think tone reveals much about the creator.

Enjoyable read but I’ll stick to The Last of Us

It looks like your choice was safe.

This is a really important piece of work. Really shows how powerful messages can be while discovered yourself through the interaction of a game. How depression introspection and creativity are all displayed here in these haunting games blew me away. Its really heartbreaking and I associated with a lot of what I was seeing and reading sadly.

Its a very well done and personal game.

Coda does not exist. Coda is Davey. He explained last year in his website that he went through a severe depression after making Stanley Parable, and while he never linked the two together directly, this game is his most likely a way for him to let it all out.

Its an excellent experience. An interactive experimental documentary. Its one of those games that you could talk about on end after finishing it.

Davey IS Coda. The whole game is an exploration of the dichotomy of developing that Davey feels. Coda originally liked making games just because he can. Not to win, not even to play, but creating just for creation’s sake. But the success of the Stanley Parable created Davey, the side of him that looked at things from an audience’s view. Davey’s persona was created because he learned he liked that affirmation that his games are good. HOWEVER Davey became obsessed with giving audiences what THEY want, instead of creating what HE LIKES. Consider the Stanley Parable. It doesn’t actually have an end. It’s nothing but blocky corridors (something he said CODA made, not Davey). It challenges the player, sometimes becoming unplayable (The baby and buzzer for example). That game was entirely Coda’s, but the success made Davey desperate to give audiences more of what’s accepted as a good game.

So once Coda randomly adds a lamppost. But Davey started reading into his own random actions. Did I add it because I liked it? Or because I wanted to signal the end of a level, which I’ve never done before?

Cool, I might give it a shot.

I just played through this game, and jeeeeesssus! It is really one of those games that you will remember for the rest of your life. Not in a “I know everything about this game”-kind of thing, but rather how unique and extremely interesting it was. How the narrative structure was presented, how the narrative itself took such a turn. It is as you say: You need to play it for yourself, don’t watch a let’s play, because THEIR thoughts, are gonna ruin the experience.. Eell maybe not RUIN it, but this is a very personal and deep story, YOUR experience lies with your own thoughts, not someone elses. (oh god that probably turned out really wrong in english lol).

Amazing game, even when there’s not much to do overall as the gaming aspect goes.

a very interesting delve into the creative process. the experience it describes is specific to gaming but most of the lessons can be applied to just about any creative work. the game didn’t resonate with me personally in any way since my career is not a “creative” one but it was interesting nonetheless.

This game looks absolutely fascinating. I loved The Stanley Parable too.

I enjoyed this game. not as much as the Stanley Parable but good nonetheless

It’s fascinating. You definitely have to be in an introspective mood to enjoy it.

Wow, this is an exceptional fascinating type of gaming concept that juxtaposes the world of gaming with philosophical ideology. Very interesting article. I am quite intrigued and will look further into this concept. Thank you for sharing such an interesting, and lesser known gaming platform.

There is very little interaction. This is not a game. Just another boring walking simulator. To make matters worse it has weird religious undertones that just get really annoying.

I always thought it ironic that the one game that actively warns against digging too deep and forcing meaning out of a creation, is possibly one of the most (intentionally) meaningful games I’ve ever played. I liked it better than the Stanley parable but that’s just a matter of taste. They were both incredibly creative.

The ending to your article hit close to home. I actually laughed out loud.

I think there’s an element of performance to how Davey got it so wrong – he wants what he sees in Coda’s work to be seen by others, and to be affirmed by others who would distribute similar praise to what he said. Davey talks a lot about how lonely Coda must be, and how desperate some of his games seem. In Davey’s eyes, all Coda needs is external validation in order to find the purpose/drive that he is missing. But the further you get into the game the clearer it becomes that even Davey becomes distressed after putting his work out into the world (beginners guide was presumably made by him after all), and that leaving himself so open to be interpreted by others just makes him even more unsure of himself and conflicted.

Coda, regardless of what Davey’s speculation on his mental health may have implied, at the very least knew that he wouldn’t change anything meaningful about his state of mind simply by having a public presence with his games.

But in the end, Davey learned that lesson the hard way.