Artistic Merit In Video Games

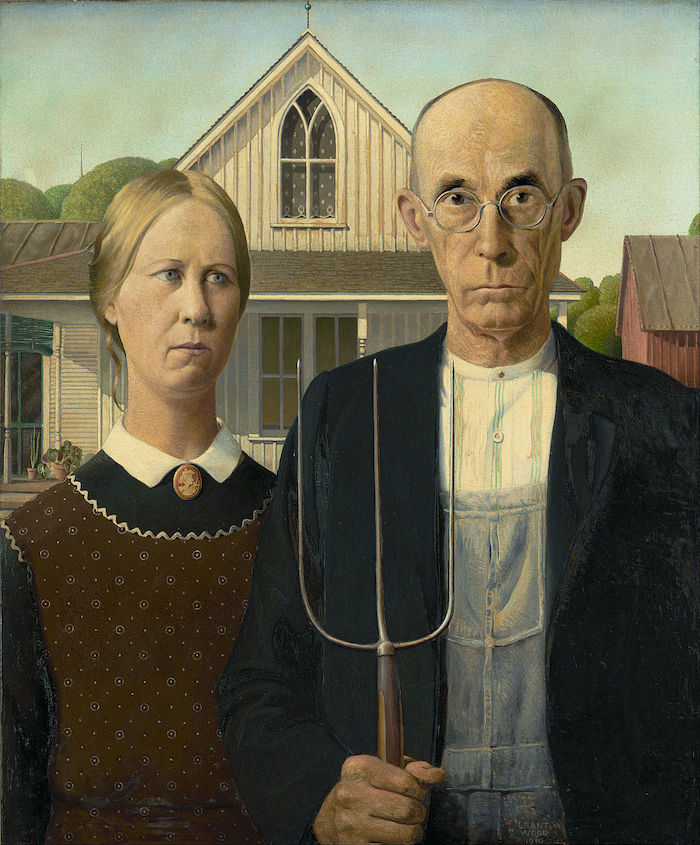

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when the word “art” is uttered?

For some, it would be a literary work from the Western canon. A work like Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) and Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967). To others, something with an audiovisual bent like Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot (1953) and Andrei Tarkovsky’s flick Stalker (1979). And if one’s to broaden the meaning of art even further, it could be something as crude as the doodles one whips up in their scrapbook.

All of the above can technically qualify as valid answers. This includes a medium that has surpassed movies and music in recent years by generating $152.1 billion worldwide in 2019. That’s compared to the “global box office industry being worth $41.7 billion and global music revenues $19.1 billion” 1 around the same period.

That medium being video games.

Video games are no stranger to eliciting the same kinds of feelings and thoughts one could draw from a painting, novel, song, or film. Feelings and thoughts made all the more potent by the interactive part of the gaming equation. Just take a look at text-based romps such as Planetfall (1983) to modern arthouse projects like That Dragon, Cancer (2015).

Games invite participants to be engaged by the experience, for sure. Most importantly, they invite players to engage with the experience through direct controller input. This helps audiences better understand the author’s imagination and ideas in a way not feasible in older mediums.

Like in literature, theatre, and cinema, ideas both basic and heady underline the foundations of a game’s design and message. A message that has something to say about the creator’s worldview and take on the medium they chose to express themselves through. It’s a fact that ought to compel developers to reach out to audiences just like playwrights, filmmakers, and authors.

This is in light of the growing support for the recognition of games as art over the past years. Evidence can be seen in initiatives such as the Game Masters Exhibition and Strong Museum of Play. Ergo, the idea of games being more than playthings has earned a spot in the collective psyche. Chalk it up to the ways in which titles like The Stanley Parable (2011) and To The Moon (2011) can make one laugh, cry, and think differently about life as a whole.

But how can one tell if a game, via its presentation and/or gameplay, does more than just entertain? What are the traits of titles that broaden and challenge one’s thinking about play and the human condition?

Tackling Novel Forms Of Play

The first sign of a game with artistic merit consists of how it introduces and presents gameplay. The game can put a spin on its genre, or craft a new one via innovative audiovisuals and controls. In any case, an artistic game can have its developers think outside the box.

This mindset’s embodied while crafting the mechanics that realize the title’s experience goal and range of feelings to draw out of players. The result can manifest in the likes of the split-screen exploration of spirit and material realms in The Medium (2021). As well as in the “Write Anything, Solve Everything” system of conjuring up random objects for puzzle-solving in Scribblenauts (2009).

How the developer shepherds players through their creation can say a lot about a couple of things. One, about how said developer perceives reality and the laws of nature governing human interaction with the wider world. And two, about the make-up of and means of traversal through the virtual environment. With an understanding of past design innovations and trends, the developers can upend player expectations regarding the artwork’s genre.

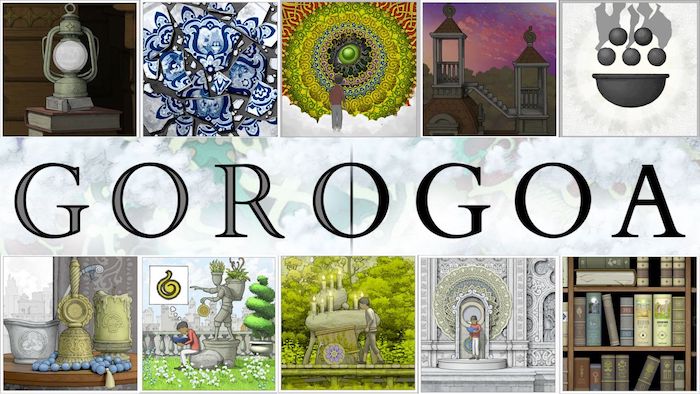

An example of mind-bending play can be found in Gorogoa (2017). On the surface, the puzzle game doesn’t seem to push its genre’s envelope. Just slide images on the two-by-two grid that makes up the title’s gameplay screen, right?

But if one were to look closer—and zoom in on said images—they’d see something more. They’d see that they’re not so much wrangling images as they are forming a narrative of 20th-century life. A narrative that sees a boy seek an encounter with an ocular monster. All while traversing an ever-changing landscape that alternates between human destruction and reconstruction along the way.

In the exploration of spiritual themes across the ages, the images’ multiple layers symbolize the boy’s haphazard memories. Ergo, Gorogoa turns the “show don’t tell” principle into an “act don’t just show” one. Players leverage their puzzle-solving chops to initiate a dialog with the author’s style of visual storytelling. In layman’s terms, the player’s helping the boy make sense of and come to terms with his imaged memories.

By engaging with the art, players can dig deeper into the imagination, thematic meaning, and history contained within each picture. They form the game’s tale—”a search for meaning over [a lifetime]” 2—like a puzzle and view it from the right angle. Bit like how the boy, as he grows older, looks at his past from the vantage point of hindsight.

Taking a chunk of the familiar and molding it into something novel can beget authenticity without losing conventionally-inclined audiences. This can be seen in the likes of Florence (2018) within gaming and Boyhood (2014) beyond it. The time-tested conventions of the medium and genre developers work in serve as springboards. Springboards for having their game transcend its trappings on a gameplay level.

Resultingly, something else shall transcend its own brand of complacency. That something else being the gamer’s approach to play. A unique style of gameplay design can snap them out of autopilot. It compels them to study and understand what’s expected of them, how to take action, and what entails from action. This reinforces the artist-audience dialog that turns an imaginative product into an exercise in creative thinking.

Other Examples: Papers, Please (2013) for its rendition of border control procedures and the dilemmas that come with admitting/rejecting border crossers; A Mortician’s Tale (2017) for relaying death positivity via its body-dissecting and funeral-home-managing mechanics; Her Story (2015) for basing its police procedural gameplay around searching databases for case-solving video clips.

Exploring Topics That Touch On The Human Condition

The developer can bend player expectations as to how a game controls and portrays challenges for gamers to overcome. They can also challenge the player’s notions about the title’s through line. Think of Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons (2013) and its depiction of brotherly bond in the face of danger. Or of Kentucky Route Zero (2020) and its magical realist rendition of weltschmerz in rural America.

Via active participation, players are more than just exposed to themes hailing from society’s and/or the author’s underpinnings. They are given a chance to explore the game’s through line via their actions. Such actions, be it for the player’s amusement or their personal edification on the title’s topic, may beget gameplay consequences. Consequences that say something about the player within the overarching theme’s context.

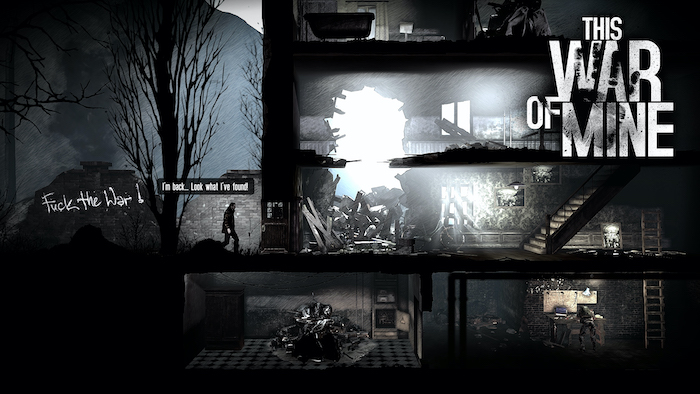

Such an experience is the kind This War of Mine (2014) aims to provide. It does so in tangible quantities that eclipse the amounts of victuals and equipment found in-game.

Taking place in a war-torn city, This War of Mine differs from other war-themed games. Instead of armed combatants, the game focuses on the civilian side of the equation. Players manage pockets of survivors and their resources in a makeshift shelter until everything blows over with a ceasefire.

This War of Mine puts a premium on humanizing those perceived as collateral damage in the theatre of armed conflict. This can be seen in the small roster of playable survivors, who embody unique gameplay traits. An example would be Zlata’s “Bolster Spirits” perk that allows her to play the guitar skillfully and boost the shelter’s morale. All of this is on top of the skill-based growth of child survivors. They can be trained to cook, filter water, and manage crops. It reinforces the importance of preserving individuality and life in the face of bloodshed. Not dissimilar to the likes of Terry George’s Hotel Rwanda (2004) and Joan Didion’s Salvador (1983).

This feeling of vulnerability in the racket of war hovers over the player’s conscience at every turn. Not to mention at every twist of the knob on the shelter’s makeshift radio. With it, players try to handle the barrage of weather warnings and economic updates coming out of the speakers. Such news put the survivors’ resources and lives at further risk via costly shelter upgrades and scavenging missions.

And the closest thing to feeling in control of things? Encountering other survivors in the outside world, and choosing to either save or kill for extra supplies. Such is the tug-of-war between materialistic desperation and humanistic integrity. All in an environment that doesn’t so much catch a break as it does catch folks by surprise with a bullet or several. This War of Mine “won’t let you forget that even when all the choices are bad, some are worse than others.” 3

A game’s heady themes benefit from informing and being fused with the gameplay and level of agency afforded to players. Bit like hiding narrative exposition under and relaying it via character conflict. Think of the side-scrolling escapade that shines a light on the gloomy world and topic of mass control in Inside (2016). Or of the Sub-Saharan romp through Heart of Darkness-like themes in Far Cry 2 (2008).

Commentary may not necessarily be seen or heard, but it can be felt even while the player’s going through the motions. Or at least think they’re going through the motions until they observe closer. By doing so, players may glean from the onscreen action the true meaning of their avatar’s doings and surroundings. A meaning that may have something sweet or cutting to say about how society thinks and operates.

Other Examples: Sea of Solitude (2019) for weaving its themes of human connection into the environment and avatar themselves; The Cat Lady (2012) for its raw exploration of depression and suicide via magical realism; Observer (2017) for having players enter the minds of NPCs, exploring their quirks and the blurred line between privacy and justice.

Challenging Player Agency And Power Fantasies

A commonly understood aspect of gaming is the idea of player agency. That is, to give the participant a direct say in how they shape and traverse the virtual world. Should the genre and developers’ intentions prove conducive, player agency can beget power fantasies. Such fantasies enable players to dominate the game’s obstacles and mold the world, facilitating the player’s virtual conquest.

But what if instead of the environment accommodating the avatar, it’s the avatar that must accommodate the environment? What if player agency was designed to teach one to study their surroundings? Rather than blindly steamrolling through them?

These are the questions that Outer Wilds (2019) answers with its Groundhog Day-flavored take on space exploration and solar systems. This can be seen in the 22-minute loop that resets whenever the sun goes supernova while players are trekking across the final frontier. They must unearth the mysteries behind the universe’s laws of nature and the extinct Nomai race linked to the temporal anomaly.

Through this info-gathering loop, players use past knowledge to more carefully venture across the stars and comb planets for clues. Outer Wilds makes it clear that they—the participant—aren’t in control of things. They are, however, in control of how willing they are to learn from life-ending mistakes. Mistakes such as not properly checking their oxygen supply or letting sand rivers in cave-ins drown the avatar.

Ergo, the title teaches players the virtue of being conscious of one’s limits. Of understanding the unknown’s supremacy in its execution of the laws of nature. This begets “a fatalistic exercise in all those adages about failure, surmised most succinctly by Henry Ford as ‘simply the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently.'” 4

And thanks to the randomized nature of the game obstacles, Outer Wilds keeps the “space tourism” factor at bay. It compels the player to be more engaged in their interactions with their surroundings. This echoes the sublime as defined by Edmund Burke: That we aren’t so much the center of the universe as we are the students of it.

Games can frame player agency and consequentiality in a way that reveals the gamer’s biases and line of thinking when under pressure. They can also highlight the delicacy and interlaced nature of the game world and its goings-on when gameplay consequences arise. This occurs when the participant’s left at the mercy of the virtual elements as in Stranded Deep (2015). And also the other way around like with tribe management simulator From Dust (2012).

By understanding how the game’s through line can be relayed, developers can further immerse the player into their avatar’s role. Success in doing so can lead to the developers’ artistic and thematic message being driven further home and into the gamer’s conscience. This turns the experience of absorbing an artwork’s emotional power into a visceral one unique to every player.

Other Examples: Tyranny (2016) for putting players in the role of the oppressor post-conquest; The Magic Circle (2015) for sporting a space that changes around the player on a whim while they try to solve puzzles and overcome obstacles; The Long Dark (2017) for teaching players survival techniques that help them respect the game’s harsh land.

Presenting Far Out Characters And World-Building

In books and films, the likes of Riddley Walker (1980) and A Field in England (2013) portrayed unorthodox figures and worlds that challenged the collective unconscious. Gaming also demonstrated a knack for immersing audiences into fictional realms and casts. These narrative components provide tangible escapism. Not to mention a novel perspective on play and the human condition itself.

The clay-based edifices and props that make up The Neverhood (1996), the pantheon of virtuous and vicious deities in Hades (2020)… The virtual space and its inhabitants advertise the sort of gameplay and narrative players are to experience. They also serve as an allegorical reflection of the state of affairs—and mind—in the real world.

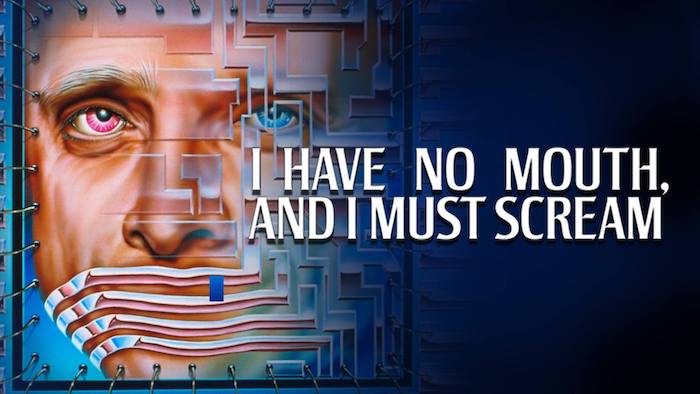

A feat that I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream (1995) achieves without no punches pulled, especially those aimed at the player’s conscience.

Based on Harlan Ellison’s 1967 short tale of the same name, the adventure game adaptation has players take control of five tormented figures. They represent humankind’s last remnants in a dystopian world run by the mastermind AI dubbed “AM.” A world made up of metaphorical adventures that exploit each figure’s fatal flaws. Those adventures draw their horror not (just) from grisly imagery, but from “the very decisions that [players] make and the [manifestation of the] sort of person that they’re becoming.” 5

The title turns the concepts of a fever dream and guilt trip into a roller coaster of taboos. This can be seen in Nimdok’s crushing sense of guilt upon learning of his Nazi past and part in the Holocaust. It can also be witnessed in Ellen’s fear of the color yellow and narrow spaces due to a past case of sexual assault. These thorny vignettes don’t so much take a dig at societal woes as they do dig deeply into the collective unconscious. By doing so, the game dredges up damning truths. The sort that the player characters must address so as to make peace with themselves, if not AM’s decades-long torturing.

Like Jacob’s Ladder (1990) and Silent Hill (1999), the game points audiences at the horrors making up the theme and parts of humanity. Horrors that may live within and around us, and that we can easily picture and confront with enough bravery and imagination. However psychedelic and disturbing said imagination may be.

Just as one personifies virtue and vice via deities, developers can make their ideas more relatable by baking them into figures and realms. So at first, I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream appears unapproachable. But then it morphs into something that one can approach and embrace if they are brave enough: The harsh truth.

Gaming—like other art forms—may hold a mirror to society and depict in it said society’s virtues and foibles. That mirror can be as bendable as the developers want it to be so as to bolster the quirkiness of the characters and world that convey the game’s themes.

Other Examples: The Wolf Among Us (2013) for its film noir take on fabled figures such as Snow White and the Magic Mirror; Doki Doki Literature Club! (2017) for its satire of the visual novel and dating game genres via its fourth-wall-breaking characters and hidden horrors; Killer7 (2005) for sporting a cast of elite assassins physically manifesting from a man’s eclectic personality.

Depicting A Unique Presentation That Can Inform Mechanics And Narrative

How a game depicts itself to the participant can set the tone for the brand of escapism and author-audience dialog said game promises. The journey that participants embark on while immersed in the experience can be shaped by the game’s framing and aesthetics. It can also be shaped by the player’s personal grasp of the gameplay and storytelling. Just like negotiating a painting’s foreground and background details.

Does the title portray itself as a puppet show like in Puppeteer (2013)? A blend of text-based and first-person exploration as in Stories Untold (2017)? Or as a note-taking simulator in the same vein as Elegy for a Dead World (2014)?

A game’s presentation can engender and modulate the range of emotions and actions that the player embodies and takes. When done well, the artwork’s presentation can wrap itself around the participant and immerse them into the title’s virtual fabric.

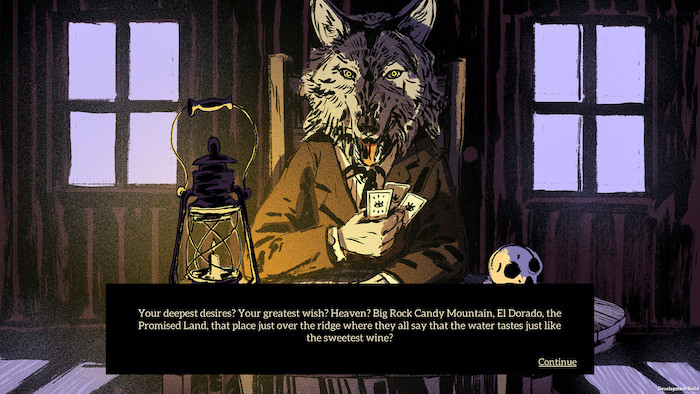

This attention-to-detail can be seen in the adventure title Where the Water Tastes Like Wine (2019). And heard as well, with players venturing across Great Depression-era America and lending an ear to oral stories from fellow wanderers. Stories that players pass along to others on their quest for meaning in a land stuck in hard times.

The folkloric factor doesn’t just apply to the sense of journey players experience while exploring the States and individual tales they gather. It also applies to the artistic flourishes. Flourishes that take cues from mid-20th century fruit crate labels and the works of Robert Fawcett. These flourishes also apply to the tarot card-style setup that categorizes the stories and underlines their respective through line.

The game spares no expenses contrasting rural American ennui with fantastical and surreal cues in the audiovisuals. As if the title’s rendering the imagination and escapism NPCs leverage to cope with hardships. This storytelling and artistic approach’s only fitting given the kinds of tall and/or innermost tales players encounter. A farmer holes herself up in her basement after the cows storm her home and take up residence. A lighthouse harbors a lamp that’ll only burn in genuine love’s presence, shining as brightly as the couple’s mood.

Beauty, eeriness, and melancholy abound in the narrative tapestry that makes up the game’s rendition of America and its denizens. That tapestry doesn’t just make for pretty artworks on the developers’ part. It also makes for a canvas the participant can fill out through the coloring and shaping of the stories they collect. The title lays bare its eclectic tone and theme across all gameplay and audiovisual facets without mincing words or details. Bit like how the NPCs open up to tale-swapping players by sharing unvarnished tales of their own.

The result? A play experience that puts as much a spin on interactive storytelling as it does on the title’s sundry yarns. The game has one think differently about how they approach, witness, and handle storytelling. Proof that “telling or retelling a story is itself a playful and participatory act, whether you do so over a campfire or in a game.” 6

As books like House of Leaves (2000) and films such as Memento (2000) attest to, a game can be idiosyncratically arranged to relay its theme. This can yield a depiction of story events and/or gameplay obstacles that challenge how players see their goals and gameplay input.

Care must be taken, however, to ensure presentational novelties don’t obscure the player’s understanding of the experience. The successful game can strike audiences as indelible, the impact never ceasing to ripple within gamers’ minds.

Other Examples: Emily is Away (2015) for using an early-to-mid-2000s chat client as its gameplay screen; The Unfinished Swan (2012) for depicting a blank world that becomes more tangible and visible with the player’s spraying of paint; Unravel (2016) for having the avatar explore environments based on its owners’ framed pictures and memories.

Drawing Emotions And Feelings Out Of Players Besides Fun

So what do all the above traits of an artistic game amount to, especially when combined to become more than the sum of their parts?

Through the presentational and gameplay, a game with artistic merit doesn’t just express the developer’s imagination and worldview. Nor does it just make gamers express their glee with laughter or sadness with tears. An artistic game leaves audiences internally moved and changed. It entrusts them with food for thought that makes them think differently about how they perceive games, art, and human existence.

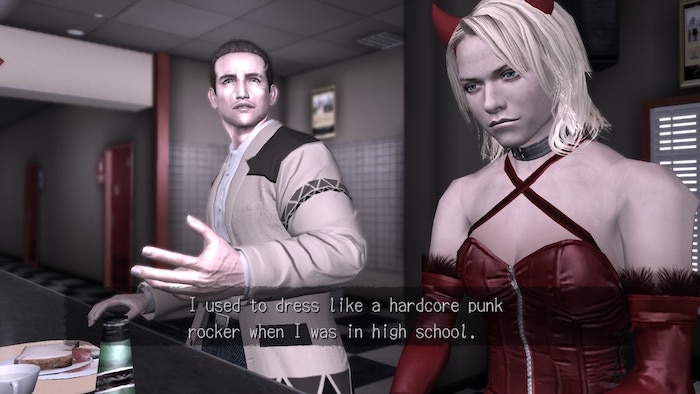

This case for emotional resonance on an eclectic scale is one that the survival horror title Deadly Premonition (2010) makes while the title’s lead—Agent Morgan—cracks a Twin Peaks-style case of murder.

Like the TV show that inspired it, there’s more to the game’s sense of mystery and rural eeriness than meets the eye. Chiefly in how disparate and seemingly incongruous elements combine into a surreal presentation. One with “its own weird logic full of zombies, otherworldly horrors, and completely inappropriate discussions of gruesome murders at a dinner table.” 7

On one end of the tonal spectrum, a gas mask-wearing multimillionaire prods Agent Morgan into trying out a turkey, jam, and cereal sandwich at a diner. On the other end, a curator tries to give a tour of her museum. Despite her tongue being cut out and shortly before getting herself crushed by a tree sculpture.

As if mirroring its polarized critical reception, Deadly Premonition‘s tone wildly varies from one scenario to another. The game invites players to look forward to their next dose of the Kafkaesque. A dose that may arise from a mundane conversation or a random sighting in the open world. It also helps contrasts the title’s quiet and upbeat moments with the damning and grisly ones.

This makes their onscreen appearances all the more potent in their intended emotional effect. Not to mention all the more unpredictable. They upend players’ expectations and the way they approach and experience mystery and small-town narratives. And when it comes to art, challenging the usual emotional takeaway from a genre work can pay dividends for the maverick artist.

When looking at how a title makes one feel and think, one shouldn’t limit themselves to the question, “Was it fun?” Rather, the weightiness of a game’s impact on the player can be measured in how it engages them on an innermost level. The feelings and thoughts elicited by the experience can be varied and/or potent enough to make a cobweb that entangles the participant’s attention. This gives the developer a chance to cast their artistic spell on the player before releasing them from the screen and controls.

Other Examples: Spiritfarer (2020) for weaving solemnity and heart into a journey about the afterlife; Thirty Flights of Loving (2012) for its rapid-fire dishing out of scenarios that vary wildly in tone and pacing from one another; Jazzpunk (2014) for its tongue-in-cheek tackling of 1950s espionage and urban tomfoolery.

In Steven E. Jones’s words, “video games are meaningful – not just as sociological or economic or cultural evidence, but in their own right, as cultural expressions worthy of scholarly attention.” Games, then, can be seen as virtual canvases onto which audiences not only admire the art, but also dive into. This creates a unique artist-audience dialog that changes how players think about their place in existence. Both virtual and fleshy.

Works Cited

- Stewart, Samuel. “Video Game Industry Silently Taking over Entertainment World EJINSIGHT – Ejinsight.Com.” EJINSIGHT, Hong Kong Economic Journal Company Limited, 22 Oct. 2019, www.ejinsight.com/eji/article/id/2280405/20191022-video-game-industry-silently-taking-over-entertainment-world. ↩

- Kohler, Chris. “The Puzzle Of A Lifetime.” Kotaku, G/O Media Inc., 6 Apr. 2018, kotaku.com/the-puzzle-of-a-lifetime-1821235999. ↩

- Sheehan, Jason. “Reading The Game: This War Of Mine.” NPR, NPR, 16 Dec. 2017, www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2017/12/16/569948674/reading-the-game-this-war-of-mine. ↩

- Avard, Alex. “How the Search for Truth and Meaning in Outer Wilds Turns a Simple Space Adventure into a Religious Experience.” Gamesradar, Future US, Inc., 15 Oct. 2019, www.gamesradar.com/how-the-search-for-truth-and-meaning-in-outer-wilds-turns-a-simple-space-adventure-into-a-religious-experience. ↩

- Kurland, Daniel. “‘I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream’: The Most Disturbing, Nihilistic Video Game of All Time?” Bloody Disgusting!, Bloody Disgusting, LLC, 20 Apr. 2018, bloody-disgusting.com/editorials/3494603/remember-harlan-ellison-made-nihilistic-horror-game-time. ↩

- Evans-Thirlwell, Edwin. “Where The Water Tastes Like Wine Review – the Joy of Sharing Stories.” Eurogamer.Net, Gamer Network Limited, 1 Mar. 2018, www.eurogamer.net/articles/2018-02-26-where-the-water-tastes-like-wine-review-the-joy-of-sharing-a-story. ↩

- Chancey, Tyler. “Deadly Premonition: Understanding Swery’s Insanity.” TechRaptor, TechRaptor LLC, 14 May 2020, techraptor.net/gaming/features/deadly-premonition-understanding-swery-insanity. ↩

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Definitely a decent coverage of some video games more in the “haute couture” circles. One of the better ones that comes to mind for me that fuses this with a high popular appeal would be Cuphead. I would best describe it as kind of like a richer Super Mario World in the 1920s if it’s protagonists were teacups. Just some thought. Good article and thanks for mentioning Doki Doki Literature Club!

Pleasure’s mutual, and thanks again for the revision notes! I agree that Doki Doki and Cuphead do scratch that artistic itch from a narrative and audiovisual perspective respectively, and it’ll be interesting to see how developers shall further experiment and leverage their imagination now that they’ve access to more powerful hardware and a more receptive view of games worldwide.

Lovely article, thank you for writing, had forgotten about From Dust and just picked it up again on sale, I always loved these sort of games ever since Populous, they just have a otherness to them that doesn’t fade after playing a long time

I concur. The Neverhood and Zeno Clash are similarly far-out titles that bask in their otherworldliness on a mechanical and presentational level.

An interesting article! I can say with sufficient confidence that I have not even heard of most of these games, so I did a lot of learning by reading this. I agree completely with the point your article makes, though. In my mind, like film or T.V. or literature, video games are just another vehicle for story-telling. So, if the others can be art, why not video games too?

Also, the cover art chosen for this article is incredible!

Thanks for the kind words!

I always think of Gris when discussing artistic merit of games. Additionally, I really enjoyed the article! Nice work on this piece!

Thank you!

Some of the most profound artistic experiences I’ve had has been through video games.

I love video games. I tried to explain it to my mom that they are like books where you get invested in the characters and world, but there is more to it than that. In video games you are actually a player. (In books, unless you’re writing a self-insert fanfic, you are only a passive viewer and not a part of the world.) Whether you are the protagonist, antagonist, or a god-like figure controlling everything. You are involved in the world and can most of the time control the outcomes and how you respond to it, good video games are often emotional experiences. I just love that in video games, you the player specifically matter.

My main problem with video games is that its yet another art form i don’t have enough time on earth to fully appreciate.

To me all the games are art, but there’s some of them who are make with only a purpose: make money, and when the art becomes a product it can’t be called art anymore.

In my school we talked about it in art class some years ago, and to me the definition of art is: put out a phrase that can’t be explained in words.

I believe video games has transcended art. Video game can convey more emotion, create more meaning, inspire more people and bring gamers around the world to play together. That is what makes video games more “special” than art. What that “special” thing is, is for you and I to decide.

Video games are definitely visual art but it’s the most expansive art medium. But I think some of the criticism stems from the fact that people still think that games are only there because you want to win.

Petty victories stimulate the brain. This is true of a lot of games, including eSports like League of Legends, DotA2, and Overwatch. But Video games as a medium have evolved pass the “pop a quarter just so you can write a 3 letter swear word to the high score table” times. It is an Interactive, Narrative Medium. It is not like most interactive art forms where you have to stand in one specific place, and unlike other Narrative mediums, you are not an audience in the traditional sense, you are part of what is happening in that world. It can make you feel so much more than any film with the right direction.

Take for example, Spec Ops: The Line. The way it was advertised was like any other military glorifying shooter but once you step into it, it makes you see the horrors of war and what it does to good men. “In war, no one is a hero. No one wins.” How about steering away from oscar bait games and talk about the pioneer of interactive story: Half-Life. Half-Life is basically like an interactive movie. But Unlike David Cage games like Heavy Rain and Detroit: Become Human, the experience cannot be replicated by watching Westworld and hitting the pause button every 2 seconds. The game world is fully interactive to a degree because of hardware limitations. The story starts out very simple but acquires depth as you move along the game. It won’t projectile vomit the narrative in your face but it is up to your interpretation of what is happening and why it is through brief moments in the game without going into cut-scenes or text scrolls and interrupting the pace. Half-Life 2, Bioshock 1 and Infinite, Doom (2016), Undertale are some of the other notable examples. Like movies, it is also an amalgamation of other art forms like music. It’s not the just music in the sense of there is music there but the use and disuse of music to create a sense of atmosphere. A recent example of this is the critically acclaimed The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

People complained about the “non-existent music” in the game. But the game actually has music but the music for the zones are used to emphasize the emotions that the game developers want you to feel. Out in the field, the music is very subtle and even cuts out entirely and you can only hear the ambiance; grass being stepped on or flowing in the wind and birds chirping and makes you feel that you are alone. But when you get to areas of interests, their themes get louder as you go towards them. The music in the villages reflect the culture of the area and usually the emotions you feel when you see them. Zora’s Domain has this air of wonder to it.

The Majestic structures built by these people. Also, when the night comes, the themes change to better appropriate. You won’t hear a very loud, and cheerful theme playing during the night. In conclusion, those who are over 40 now who don’t recognize games are art will someday die and it will become a legit art form…

I didnt know how to express my point of view until you literally wrote it, videogames are not about winning anymore, at least not in some cases. And great article for sure

My dream in life is to start a new game studio and create amazing artistic video game experiences.

I’ve been playing video games almost my whole life. Some of my earliest memories, besides my parents’ younger faces, are of Pokemon. This medium has formed such a massive part of who I am as a person, and it gets exhausting, having to defend its legitimacy as an art all the time.

There’s no solid counter to games being art. Video games have literally every major art form, literature, visual art, music, acting. Video games are the epitome of art.

Video games are just as valid an art form as film or literature, with just as much ability to resonate with viewers emotionally and intellectually.

Not only are Video Games Art, they are far superior to any other existing art forms.

Haha that’s a very close minded way of looking at art imo. there’s not superior art forms, there’s just different art forms that different people can enjoy.

You are right but you are also wrong. There is no way to quantifiy arts value. But if you consider the standards most art critics have to art, then video games are far superior. They contain almost every other art form usually. The interactivity and the immersiveness allow for a much more layered form of telling a story than movies or books ever could. This is what i mean with “superior”. When it comes to the actual value of art, you are absolutely right! It is not possible to say one form is better than the other.

Really good article. Shared with my friends. People who don’t think video games are art are the same who think video games are all about points, collectibles and levels. It’s like saying “Transformers is just a cliched money making fodder entertainment hence all films are not art”. Kinda outrageous.

Thanks for the kind words and share! Like all novel art forms—including films and comics—it’ll likely be a matter of time before most, if not all, of society embraces the new.

Video games have always been an artistic form. I love them. They’re artistic, creative and imaginative. I think people who criticize video games are the boring types of people I dislike. Of course, games are art forms. I personally think that Shakespeare and his plays are boring. I don’t see what’s so interesting about Romeo and Juliet, and I never have. I’ll never understand people who hate video games. You can be cultured, well-traveled and empathetic while playing video games at the same time. Soap operas are boring, stupid and full of superficial types of people and constant drama yet no one seems to complain about the complete pointlessness of such T.V. shows. Grey’s Anatomy and Scandal are boring shows that people waste their time watching on Netflix. I guess we all criticize the things we dislike.

I see it as a big canvas how you are able to create something of that game through your own experience. They are made with visions people who sees a big picture and visually shows it to us players through their creation and let us experience it for ourselves and in our own pacing.

Thank you very much! I always try to explain how video games are art (or at least how they can be art), especially to adults who are always saying “video games are violent blabla, young people shouldn’t play video games, it makes them violent too, uncultured, blabla” even though they don’t know anything about it and barely heard of it.

I love video games since I was 7 and got the old (then already really outdated!) C64 of my father to play with it. And I love the games because I can explore new worlds like I can do in Books or movies or Paintings, but in my pace and my often it’s my choice what I want to explore next! I’m so glad that games nowadays often are seen as art and not only as a quirky thing only freaks and nerds do.

I really recommend GRIS. It’s the only game I immediately preordered the art book for. Beautiful art, music, and storytelling with simple controls and my favorite part – you can’t die in the game, so there’s a lot less frustration.

When games can emotionally move you without the use of other mediums and only does something a video game can do, that’s when it becomes an art. Spoiler for the shadow of the colossus – the scene at the end when Wander is being pulled by the fountain and the player is completely in control and it becomes the player’s choice on how long they want to resist, that’s when games become art. The narrative and music are there to drive the player to that one moment, and in that one moment, the game does something only video games can do, it puts you in control. You aren’t watching Wander fight… you are fighting with him. Games can be art. I have been moved by a games visuals, music, and narrative, but playing that sequence in SotC was the only time i was moved by gameplay.

Is music art? Yes music is in video games.

Are movies art? Yes video games can have stories on level with movies even better sometimes.

Are paintings/drawings art? Yes video game box art.

Is writing art? Yes video game scripts.

Are video games art? In my opinion yes.

Anyone who argues that games aren’t art, play Silent Hill 2 and ask yourself that same question. Play a visual novel, JRPG, or a crafted platformer like Hollow Knight. The level of cohesive art direction in some video games is well on-par with cinema and even exceeds it at times. There are stories you can never tell in any other medium. It’s not only an art form, but one of the most immersive and engaging ones at that.

Google believes games are not Art. Their news service categorizes all game news under Technology, not under Arts and Entertainment.

Technically they are technology…

If you like a game and it added to your life doesn’t that make it ‘art’? after all isn’t art all about the individual and what people get out of it? so if someone likes a game and thinks it is art but it isn’t unanimously praised as art does that mean they’re wrong?

In case you’re interested in a videogame that really needs to be in the medium it is in, look for the Russian indie game Pathelogic. It is not really that fun to play (as that kind of is the point) but it is really interesting thematically and structurally. It manages to say a lot about videogames as a whole, without doing anything else than asking questions. I would honestly say it is one of my favourite recent works of art. Another one would be The Begginer’s Guide, which is video game’s equivelent of the treachery of images.

Lovely read. Gaming has had such a huge impact on my life, I don’t know who I would be without it and the credibility that it gives to the idea of video games as an art form is really validating.

I’m not a big gamer (i just lack the coordination!) but i recently played a game called “what remains of edith finch” that was absolutely a piece of art. I kept thinking, wow this game is like a graphic novel! but really, there was no other way to tell quite that specific story in any way other than a game and i’m so glad i got to experience it.

Another thing that I think is worth mentioning when talking about video games as an art form are mods. This is something that is unique to games, you can’t just walk up to the Mona Lisa and add a mustache (unless you want to get into serious trouble), but with games, if you prefer the dragons in Skyrim to look like Thomas the tank engine, there’s a mod for that. You want your Sims to be naked? Mod. You want to romance the straight character Cullen from Dragon Age Inquisition with your gay inquisitor? Mod. There are even mods that turn a game into an entirely different game, new characters, new story, new everything, like Enderal. It adds a whole new level of interactiveness, not only can you interact with the game within the limits the developers set, you can bypass those limits completely.

That’s exactly a good reason why they aren’t art. Art is the vision of an individual.

Why do you define art that way and why do you think that makes video games not art? Movies are usually made by multiple people, are they not art? If a sculptor and a painter work together on a project, is it not art? And talking about modding: Why does the possibility to change a work of art make it any less of a work of art?

Great article. It definitively has challenged some of my viewpoints on the artistic merit of video games. I appreciate how your approach was multifaceted.

Thanks for the kind words!

I see games as art, but I also think it’s ok if we see them as Sport or Trash, too. Kind of like how Federico Fellini and David Lynch can make art in the same medium as Michael Bay.

Good post. And this is why it’s important that they DO NOT censor our games.

One of the best video game I’ve ever experienced as an art form is: Red Dead Redemption 2.

The others are up there in my opinion are: Last of Us and The walking Dead S1.

To me anything that can move you is considered art, the last of us, Journey for example.

It’s been interesting watching the dichotomy of indie games pushing more for their own style of artistic merit while triple-A titles seem to want to follow in the footsteps of film and television. Though it’s likely this is just the usual entertainment industry standard of ‘follow the leader’, I can’t help but feel it’s also because developers are trying much too hard to have their games be recognized as genuine stories, by just telling stories that could’ve been told in other formats.

I’ve always had a deep connection to creation, self expression, storytelling and video games are no exception to these themes.

Art is what I call Outer Wilds, a game that guides players through the story just by our curiosity and just that with a beautiful soundtrack.

Really well written article, though I don’t know if I agree exactly with the premises. The argument doesn’t commit to a definition of what art actually *is*, and it instead points towards examples of art. If these qualities are present in other mediums, what exactly is it that makes ‘video games’ distinguishable? The same traits enumerated here could be applied to many other activities that we do not strictly consider as ‘artistic’: sports, for example, share many of these qualities for both participant and viewer. An objection I would raise may be that video games, though they are artistic, are primarily a technological development of other kinds of media such as literature and film. Hence, though a video game maybe aesthetically pleasing, and therefore has artistic merit, I would hesitate before coming to the conclusion that it can properly be called Art.

I have cried at video games, cheered and just stared in awe.

Currently developing a thesis on this for my philosophy and art class. Will reference your article. Thank you.

Swell to hear! Feel free to share your work with me whenever you get the time to do so. 🙂

Id rather have fun gameplay mechanics than a deep story. If i want that then i go watch a movie. I only like them if they are very artistic.

What is closer to art than something that allows you to experience another reality?

I’ve been trying to convince people of video games validity within the art world and you’ve summed up my arguments beautifully.

Thanks for the kind words! 🙂

Life is strange is the most artistic game I have ever played.

Nier: Automata disagrees with you.

There are video games, and then there is video art.

To me art is something that you find meaning in.

Thank you for the recommendations :). I’ve recently gotten a newfound passion for exploring and interpreting video game aesthetics, especially indie ones.

Yes, video game art is definitely not given the recognition it deserves, thank you for this deep and thoughtful analysis!

You did a wonderful job talking about what makes games so incredible as an art form, I would love to hear your thoughts on “Before Your Eyes (2021)” since it encapsulate many of the ideas you presented.

There are some excellent analytical points in this piece. The ending, pivoting from fun to meaning, seems to be the thesis about art. Outer Wilds is a great case in point. Is it fun to wait for the sand to drain on Ash Twin to access the warps? Nope. But while you wait, you watch. You hear. You get zapped by the sand column because you under estimated your distance. But that communicates something deeper than fun.

I really like the art and style (and how its music manages to aid the mental health) of OMORI. Something about its psychological horror mixed with almost child-like creations of art is unsettling.

A great discussion about an interesting topic. Absolutely games are art and some are more art than what we label “art” in the mainstream world. Thanks for sharing.

Excellent points, the games that invite you to think about the world differently through their gameplay often garner appreciation. Games allow the audience to engage in the role of not just a viewer or audience member, but an actor. They can give players agency and a level of dominion over the world of the story, and in some cases (like Papers, Please and The Stanley Parable) invite them to question or even doubt their own role, agency, or morality. This leads to a new, careful perspective on larger issues and contributes again to the point that games can send unique messages in unique ways. They allow us to explore possible worlds with intricacy and vigor that can’t be matched elsewhere.

Interesting read. I think the fact that video games can elicit such visceral feelings from its players (from emotions like grief, excitement, sadness, anger, and joy just to name a few) alone demonstrates its relevancy as an artistic medium, not unlike film and literature.

This went so much further into what makes games art and how. As an emotional person, the most important games, and one’s I feel are art, are the one’s that give me an emotional response. Your article gave me a really good insight into the scientific, personal and humanistic qualities that make games art.

Also, huge kudos for including Killer7. It’s my #1 game and to see it here made me so happy.