The Witcher Series: The Mastery of Adaptation

Adaptations on adaptations on adaptations is one way to describe the grossly popular Witcher game series. Another way would be: Game of the Year, Best Storytelling, Best Visual Design, or any of the other award title that the series dominated over when its third installment, Wild Hunt, was first released in 2015. Developed by the Polish based company CD Project Red, which won Studio and Developer of the Year, The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt increased its revenue sales eleven times more from The Witcher 2: Assassins of Kings and drove over a million people to pre-order copies. At its core, The Witcher series is a fantasy-rpg much like many other top-selling games like the Elder Scrolls, World of Warcraft, or Dragon Age, but what makes this series so unique from its contenders? Adaptation.

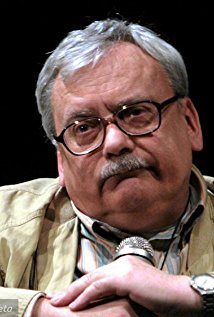

Andrzej Sapkowski and the origin of the Witcher

The Witcher game series is ultimately an adaptation of The Witcher novel series written by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski. Despite graduating as an economist and having great interest in Polish history, Sapkowski is one of Poland’s most renowned contemporary authors; being compared to the likes of Neil Gaiman and China Mieville. He is a five-time winner of the Janusz A. Zajdel Award (an important honour for fantasy writers) and has received the Polityka magazine’s Literature Passport Award in 1997. In 2009 the final instalment of The Witcher series, The Blood of Elves, received the David Gemmel Fantasy Award, and in 2012 he was awarded the Medal for ‘Gloria Artis’ (Merit to Culture). Deferring from his economic training, Sapkowski writes novels, fantasy stories, essays, and dictionaries about the fantasy genre such as the world of King Arthur, and the Dragon Cave Manuscript.

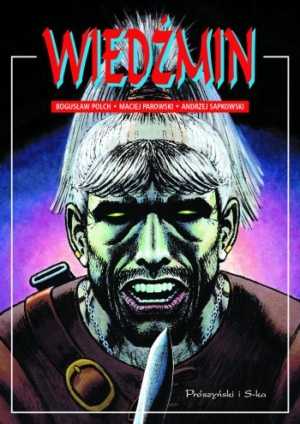

In his early career, Sapkowski first started working as a translator for Fantastyka magazine. The Witcher first made his appearance in the very same magazine when in 1985 Sapkowski’s short story Wiedźmin, “Witcher”, won third place in its fiction competition. Geralt, the main protagonist in the Witcher, began to come to life when Sapkowski continued to publish his first adventures in Fantastyka. Later, Bogusław Ploch wrote a comic based on the short stories from 1993-1995 that Sapkowski personally illustrated. Growing in popularity, after having finished writing The Witcher novels, Geralt’s story was adapted into a poorly received film (2001) and the television series Hexer (2002) both directed by Marek Brodzki.

Mariusz Czubaj, one of Poland’s top scholar in cultural anthropology who specializes in the culture of fantasy, described the author’s writings as:

“a form of polemics with the Polish tradition of the historical novel, with let’s say Kraszewski and Sienkiewicz, who wrote about cruel times while depriving them of that dose of atrocities and a most basic human dimension. Yet the author of ‘The Witcher’ does not hide that his characters are not exactly subtle, but who nonetheless bask with delight in what the literature theoretician Mikhail Bakhtin once called ‘the material bodily lower stratum’.” (Translated by: Helena Chmielewska-Szlajfer)

Czubaj references that Sapkowski utilizes Bakhtin’s theory of the carnival (carnivalesque) versus grotesque realism (grotesque body), which aims to degrade abstract, spiritual, noble, and ideal concepts into a material level. This idea of the carnival versus grotesque body is perhaps what helped make The Witcher series so outrageously popular — it deconstructs the status quo of what fantasy (and by extension to fantasy in video games) should be. Traditionally, fantasy video games follow the Anglo-Saxon history of folklore when constructing fantastical universes. As an extension of this tradition, Tolkien’s mastery of history and linguistics also helped to further shape modern fantasy and helped re-popularize the genre as a whole, but his works have ultimately become the standard. Unlike other video games, The Witcher is not only an adaptation of the novel series, but Sapkowski’s novels themselves are structural reworkings of folklore based predominantly on Anglo-Saxon, Norse, Celtic, and Slavic cultures.

Anglo-Saxon Folklore

Recognizable by a larger audience, Geralt’s adventures, both in Sapkowski’s novels and later adapted into quests, are (if possible) more gruesome interpretations of Grimms’ fairy tales. In the novel The Last Wish, an instance of this is during the short stories titled “Lesser Evil” and “Question of Price”. Based on Snow White, “Lesser Evil” focuses on a princess destined for evil due to a prophecy. Brutally raped by the Hunter who was meant to kill her, Renfri (Snow White) killed the Hunter, and lead a life of thievery in order to survive. She became a notorious assassin with her signature killing method being impaling, and gathered a band of merry, murderous dwarves. After surviving an assassination attempt from her step-mother via poisonous apple, Renfri decided it was time to take revenge and took back her kingdom and even became the favourite mistress of a rich prince. So why doesn’t she live happily ever after? Because her ultimate victim is the wizard who prophesized her demonized existence. In its skeletal form, Sapkowski mimicked the plot of the traditional Snow White in a carnivalesque fashion. A princess is wrongly accused by her step-mother, the hunter tries to kill her but fails, she meets some helpful dwarves, marries the prince, and regains her rightful place in the kingdom. The grotesque body manifests in the prophecy that damned her existence, her horrific life, and the question: is Renfri a monster because of her birth? Or is she a monster because of the terrible circumstances of her life? The answer is never truly clear and neither is the ‘lesser evil’. Does something like that even exist? Geralt (and perhaps Sapkowski) seem to think it doesn’t.

Another easily recognizable Grimm character is Rumpelstiltskin in “Question of Price” which is also found in The Last Wish and as a quest in the video game. Despite not being a major character, Sapkowski’s “Rumplestelt” follows a similar plot formula of offering help in exchange for a princess’ first born. However, the grotesque body is brought into play once again to teach a lesson that destiny should not be trifled with. In The Witcher universe, there is a rule of destiny known as “The Law of Surprise” that can be used as currency. The rules of the law dictate that you must give up a gift to the saviour that is currently unknown to the saved. This can be anything from alcohol, a pet, or a child – and in most cases, it is always a child (“The Law of Surprise”). In the “Question of Price”, when enacting the Law of Surprise, Geralt reminisces on what happens to those who choose to ignore destiny. When the princess, Zivelina, refused to give Rumplestelt her first-born, both she and the child died by plague.

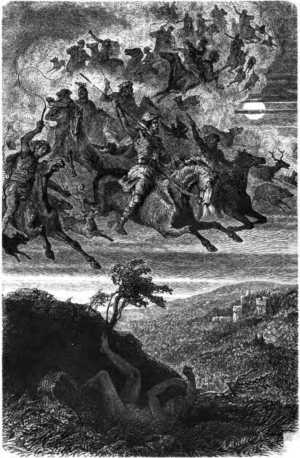

Moving away from Grimm’s influence, the concept of the “Wild Hunt” is actually apart of Germanic and Scandinavian mythology. In Old Norse, it was called: “Oskoreia ‘Terrifying Ride,’ or Odensjaakt, ‘Odin’s Hunt’. In Middle High German, it was called Wuotanes Her, ‘Odin’s Army,’ and in modern German [das] Wütende Heer, ‘Furious/Inspired Army,’ or [die] Wilde Jagd, ‘Wild Hunt’.” (“The Wild Hunt”) Also known as an ethereal, nocturnal horde, the Wild Hunt was believed to happen during the dead of winter when it was the coldest, darkest part of the year and icy storms ravaged the landscape. During this time, if anyone dared to come outside they could witness the procession or be unfortunate enough to be detected and taken by it. Some practitioners of magic could apparently join voluntarily by selling their soul to those of the Hunt.

More so found in the games than in the novels, there are also small references to Arthurian legends such as a silly instant where Geralt tries to pull the sword – Excalibur – out of its stone. In the DLC Blood and Wine the “Lady of the Lake” must be consulted during the quest “There Can Only be One” in order for the quest to proceed. She, in turn, will give Geralt Aerondight which is, according to myth, the name of Lancelot’s sword.

Norse and Celtic Folklore

The Wild Hunt also makes an appearance in Sami culture (located in the Northern, arctic regions of Norway, Sweden, and Finland). Author Johannes Scheffer, author of Lapponia in 1673, described a similar spectral army in which the Laplanders (Sami people) would make offerings to what they called “Yule Folk” (The Wild Hunt – Germanic Mythology”). Returning more towards a Norse and Celtic perspective, the infamous Ragnarök or “Fate of the Gods,” (a.k.a. the end of the world) is believed by the Skelligers as “Ragh nar Roog”.

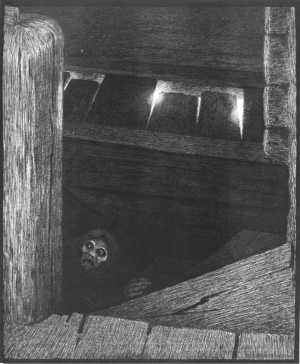

Norse influence is mostly found in the beasts that plague the Witcher universe. Botchlings, or mylings, are known as phantasmal reincarnations of unbaptized infants that died. The myth having come into being during a time when infanticide was popularly practiced in secret, mylings would wreak havoc until someone kind enough could give them a proper burial. Curiously, the demonic myth of the botchling is also seen in Slavic folklore where they are known as a poroniec (derived from the Polish word poronić “miscarry”) or drekavac (Serbo-Croatian word for “screamer”). Associated with sexual malpractices of women (sexual deviance, miscarriages, stillborn, improper Catholic burials) a poroniec is a demonic creature that arises from the dead in rage. However, in Slavic traditions, if buried under a threshold the poroniec could turn into a kłobuk (“lubberkin”). Another Norse beast (that also shares roots in Slavic folklore) are the plague wraiths. Known as pesta “plague hag” in Norway, the plague wraith was essentially the personification of the black plague that atrophied Europe in the fourteenth century. A common theme in explaining terrible occurrences, the personification of the plague was also seen in Lithuania, Russia, and Poland as the morowa dziewica “plague virgin” as identified by the Polish Romantic poet, Lucjan Siemieński (“The Myth behind the Monster of Witcher 3”).

Expanded upon in the game more than in the novel, the culture of Skellige is distinctly Celtic in origin. Skellige itself is a direct reference to the Irish Island “Skellige Michael”. Ard in Irish means “high” while an means “the” therefore, Ard Skellige and An Skellige can be translated to “High Skellige” and “The Skellige”. Clan names of the Skelliger also come from Gaelic and Scottish influence as clans Drummond and Tordarroch are real clans in Scotland, while Craits in Gaelic means “shaker”. Their clothing also reflects Celtic culture found in Ireland and Scotland (Phooka12, “The Gaelic/Celtic Culture Influences of the Witcher 3”). Another curiosity is that Elvish speech in the game is heavily based on Gaelic languages (“Elder Speech”).

Slavic Folklore

It is undeniable that despite drawing from the cultures and folklores of Europe, Sapkowski’s (as well as the developers from CD Project Red) greatest influence was from his own Slavic background. A unique concept taken from Slavic folklore is the “Witcher” itself. Roughly translated from the Proto-Slavic vědě “to know” a Witcher is essentially a warlock. However, unlike their witchy counter-parts, Witchers are seen as both figures of good and evil (“Witcher”). Possessing this likeness of “good”, the concept of the Witcher has been connected to the “cunning folk” of Britain, otherwise known by its rarer terminology “white witches” (due to the negative connotations associated with ‘witch’) (“World Goes Wild for the Witcher 3: Wild Hunt”).

Slavic mythology mostly manifests itself in the demons and beasts that terrorize Sapkowski’s world. To name a few, the already mentioned poroniec “botchling”, bies “fiend”, czart “chort”, leszy “leshy”, rusałka “rusalka”, strzyga “striga”, kikimora “kikimore”, and południca “noon wraith”. These are all examples of beasts that are totally unique to Slavic mythology, although (as shown with the botchling and the plague wraith) similarities can be found within other European mythologies. Perhaps the most intriguing addition to this monsterology are the Panie Lasu “Ladies of the Wood” otherwise called: Wiedźmy z Krzywuchowych Moczarów, “Witches from Crooked-Ear Swamp”; or by their much simpler English translation: the Crones. These three demonic figures are a direct reference to the infamous Baba Yaga. These cannibalistic ladies may not live in a hut standing on a chicken leg, but they do have a candy trail that leads to their lair deep within the marshes. Despite their monstrous approach, the Baba Yaga fundamentally is a “helpful old hag, ugly to be sure, but willing to give advice that will save the virtuous heroines and heroes,” as folklorist Paula Kiska explains in her article “Wonder Tales”. Within her analysis, Kiska notes that the greatest details within folklore, are those generated from archaic and primeval folk traditions and also as a way to explain the unexplainable. For instance, noon wraiths, were most likely a way to explain heat stroke during long summer months, the same way that plague wraiths explained disease. Despite the Crones being one of the main antagonists in the game, they fulfill the archetype of the old hag by never backing down on their word and always willing to help, but of course, only for a price (usually) drenched in blood. Unlike the noon wraith which is used to explain a natural phenomenon, Baba Yaga’s origins have a godlier explanation — she was the deity of death and regeneration, which fits quite comfortably with her general M.O. (Baba-Yaga). Life cannot regenerate without death. In the quest “Ladies of the Wood” the Crones told the Bloody Baron’s wife, Anna Strenger, that they would not help her miscarry, unless she offered her own life in servitude. The three-in-one manifestation of the Crones also twists quite coherently with Baba-Yaga’s god-like history as in variants of her story, especially those from Russia, she is often depicted as a being of three.

Beyond these direct references found both within the novels and the game, CD Project Red adds small decorative elements within the universe to help accentuate details of Slavic culture, that are not completely obvious to foreigners. The most prevalent of these would be the flower and straw chandeliers that hang in village houses. Known as pająki “spiders” that are predominantly found in Poland, they are “connected to old Slavic rituals performed for the winter solstice and the spring equinox,” as a symbol of protection (“pająki — protective decorations made of straw”).

The written language used by the humans in the Witcher is the Glagolitic alphabet. To simplify a very complicated history, the Glagolitic alphabet is the oldest, original alphabet to appear within the Slavic world. It was ‘artificially’ made (accredited to the Holy brothers Constantine and Methodius) created specifically to match Slavic phonetics (specifically Old Church Slavonic) and to aid Christianization (“Glagolitic Script as a Manifestation of Sacred Knowledge”). Predeceasing (and fighting for domination over) the Cyrillic and Latin alphabet in the Slav world, Glagolitic would make an impact in almost all Slavic states, but gained most ground in Croatia where it was used regularly for liturgical purposes until the 19th century (“The Three Languages and Three Orthographies of Medieval Croatia”). Another small curiosity is that the runes used in the Witcher game are named after Old Slavic gods such as Perun who was the equivalent of “Zeus” in the Old Slavic pantheon (“what is Known About Slavic Mythology”). Within the greater Slavic framework lies an element of Polish-isms that is enhanced within the novel and video game as small nuances too complex to be filled simply under the category of “Easter Eggs”. In the Polish iteration of the game, when speaking to Vesemir, Geralt makes a comment about a fairy tale about an old bear who is sleeping. In Polish, this is a reference to the nursery rhyme “stary niedźwiedź mocno śpi” which is a similar version of the game “what time is it Mr. Wolf”. Another instance of this is when speaking to Dijkstra during the quest “Finding Count Reuven’s Treasure” in English Geralt makes a reference to the tale of Hansel and Gretel, which in the Polish dubbing is translated to the Polonized version of the tale called Jaś i Małgosia “Jack and Margret” (where the candy-crazed witch who tries to devour them is none other than Baba Yaga). Other references include historical myths such as when dziady, or Forefather’s Eve, which takes place (as a reference to the old Slavic pagan Halloween as well as a work of Mickiewicz – more on that in a moment), near the tower of Popiel, who was a legendary Slavic prince.

Role of Polish Romanticism

Among the adaptation from folklore, The Witcher novels and video game heavily draw from Polish Romanticism. Fundamentally different from English and French Romanticism, the Romantic era of Poland was much more grotesque than what its Western friends experienced. Although sharing similar philosophical ideas such as the focus on self, the glorification of the past and nature, these concepts would be corrupted by sacrifice and national cause after the partitions of Poland when the country ceased to exist; and after the failed uprising of 1830 to regain its stolen liberty. Emotions of “pessimism, melancholy, and metaphysical and political rebellion were countered by messianic ideas of the émigré poets,” which lead to a rise of a Catholic inspired messiah complex and recovering a lost, pagan, past (Oxford Handbook: “Polish Romanticism”; Schreiber “Polish Romanticism”). These ideals themselves are evoked within Sapkowski’s novels with political disarray, rabid patriotism, and a return to something mystical before it ceases to exist entirely. Although Sapkowski plays on concepts of Polish Romanticism, the video game more heavily adapts tales from this period.

Most obvious, within the Polish dubbing, is that Dandelion often recites poems from the Polish Romantic period. The most explicit of these references was during the quest when Geralt confronts a Midday Lady. The quest itself is based on Juliusz Słowacki’s Balladyna but after the wraith is defeated, Dandelion recites a fragment from Mickiewicz’s Upiór “The Ghost”.

As previously mentioned with dziady, the quest plot within the game mimics parts of Mickiewicz’s most popular poetic drama Dziady “Forefather’s Eve”. Similarly, in the DLC Heart of Stone, the plot is based of the Polish fairy tale of Pan Twardowski “Mr. Twardowski” (in which the root word is twardo “hard” – meaning his name could technically translate to Mr. Hardcore) who sold his soul to the devil (variants include the ‘devil’ being a bies or czort) for magical powers. He then summoned a massive rooster and flew away on its back to the moon – go figure, but I guess you could say that’s pretty hardcore. Despite Pan Twardowski being a fairy tale, his story heavily inspired ballads by writers such as Mickiewicz and Moniuszko. The expansion also draws paralelles to Stanisław Wyspiański’s play Wesele “Wedding”. Even the quest “A Tower of Mice” is directly taken from another work of Słowacki’s called Król Duch “King of Ghosts” which, again, references the legendary prince Popiel.

Beyond direct poetic exerts, the devastated landscape of Temeria, as analyzed by Paweł Schreiber for Culture.pl (an official publication run by the University of Adam Mickiewicz Press in Poznań), is also taken directly out of the melancholic eyes of Polish romantics. Wooden houses amongst fields of flowers with strange creatures lurking behind every nook and cranny is taken out of the creatively disturbed mind of Mickiewicz in Ballads and Romances, while the landscape surrounding Forefather’s Eve is much more complex:

“this is how Juliusz Słowacki described the area around Gopło lake in a letter to Zygmunt Krasińki in the introduction to Lilla Weneda. This is obviously not the real Gopło, but the lake according to The Poems of Ossian, which were very popular at the time. It is basically a proto-Slavic and Celtic fairy tale hybrid based on the pseudoscientific treatise Pierwotne Dzieje Polski (The Ancient History of Poland) by Henryk Lewestam, adapted to fit Europe’s main concerns at the time. In it, the original inhabitants of Poland are Celts, while their leader, Dervid is a ‘copy’ of the Shakespearean Lear.” (“How the Witcher Plays with Polish Romanticism”).

The Role of Adaptation

Despite the many Slavisms that are entrenched within the atmosphere of the books and the details of the game, it is undeniable that what makes Sapkowski’s novels and The Witcher video game series so relatable is that there is a bit of everything. Everyone can recall some bits and pieces of folklore and fairy tales from their childhood when interacting with the material while also given the opportunity to discover something new. Furthermore, what makes this type of adaptation so intriguing is that Sapkowski has degraded the concept of folklore into a grotesque realism that makes it more relatable to our political climates and mentalities today. The game further deconstructs this by creating a cultural melting pot that combines histories together. By adding in smaller references, what the game does is enhance the material of the novel with intertextual references. What makes the Witcher game series so successful with its book-to-game adaptation is because it relies on these multiple layers of intertextuality and short story functions. Geralt’s life is tumultuous and delivered as a nonlinear narrative. The game is able to adapt Geralt’s adventures within the novels to quests, whilst enhancing and expanding content that Sapkowski has already utilized. The use of short story structures not only helps make quests in the games within the greater plot, but also supports its RPG purposes. Geralt, despite being ‘destined’ for Yennifer, still has romantic relations with many other women, but also doesn’t have the healthiest (or monogamous) arrangement with her. Since the novels don’t piece their unison chronologically, the developers are able to manipulate those events so that players have a choice within events while staying true to the novels. After all, Sapkowski himself explores the struggles of choice and the philosophy of bias behind a ‘lesser evil’.

In her article “Adaptation, Intertextuality, and the Endless Deferral of Meaning,” Ilana Shiloh explains that “any text is an amalgam of others, [that forms] a larger fabric of cultural discourse,” that, as elaborated be Robert Stam, is meant to become an “evershifting [grid] for interpretation.” When interacting with Sapkowski’s novels, the reader is meant to feel a sense of nostalgia whether it be through Grimm’s haunting tales, the climate of Polish Romanticism, or creatures that extend beyond Europe such as the Djinn or “genie” that hails from Islamic mythology. The game further enhances what Sapkowski adapted to create The Witcher into widening the spectrum of not only adaptation, but the intertextual references that come with it. The Witcher series has seen widespread success throughout all of its adaptations because it itself is an adaptation of a variety of common myths from different cultural backgrounds, that have been simplified by the author for a diverse audience.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Witcher three is a masterpiece to me. It has a “sense of place” that is the best I have experienced in a game. The only game that comes close in my mind at establishing a coherent world is The Zone from Stalker: Shadow of Chernobyl.

Definitely embodies a very specific sense of place. And thank you for the recommendation! I was struggling to find a game that could match up to that same level of world building.

Best RPG ever. I haven’t cried at a game before but when Vesimir… oh god….

I actually broke down even before Vesemir – at Baron burying his dead child, at Geralt reuniting with Ciri. Such a damn masterpiece.

Great article, Pamela, thank you for wording my thoughts about the Witcher better than I could ever have.

Thank you!

I personally enjoyed the original Witcher game more than any other game I’ve ever played, and thought it magnificent (despite the irritatingly limited game world, and ridiculous fences and no-go areas; but have found The Witcher II, although beautiful, very difficult to get into. I’ll buy the third game, but mainly out of gratitude for the first; we’ll see how it goes. At least all the reviews have been praising it.

And also, the second installment of a trilogy is often the weak one.

I would highly recommend the third! It’s truly a stunning game visually and I’m always blown away by the amount of detailing that goes into the multiple layers of storytelling and character development. They really do a spectacular job of adapting into an rpg and building on small moments in the game without spoiling the content of the novels.

I’ve just finished the last of us so was looking for something else to get my teeth into – sold!

I’ve never played 1, and only bits of 2 and love 3. Thanks for the great analysis.

This is a spectacular game series. They have that “just 5 more minutes” quality which the most enjoyable games have.

What a great Article about a great game! Very well written, and amazingly well investigated! Send Runes!

This article perfectly explains what makes the Witcher series so amazing.

I wish all adaptations of other media into games could take notes from what CD Projekt Red has done with this series. The passion and care just oozes from this series.

thank you so much! I definitely agree. CD Project Red is extremely passionate and I can’t wait to see what else they will create! As for adaptations, I completely agree. A lot of video games flop because they fail to live up to their book/film parents. Actually, if I’m not mistaken, I think LEGO series are another amazing example of video games that have mastered adaptation and source material.

Absolutely! Adaptation is a delicate balance between respecting the source material, but also making it one’s own so that it stands on it’s own merit as a piece of art.

Great and thoughtful write up. I think the only real disappointment is we likely won’t get another RPG as good as this for years. Hopefully something out there is set to come from nowhere and surprise us.

I completely agree! I’ve been struggling to find something that compares in terms of excellent narrative and genuinely fun gaming.

Bravo! Well written article, this is why this is possibly my favourite website! This made me think of the games story more and it really is something too rare in gaming, truly good writing! The game series is such a brilliant piece of work.

Thank you so much!

I feel that there’s a level of immaturity to some of the delivery in the games… particularly the second game.

W3 game has some of the most awkward/awful movement combined with the most awkward/awful combat that combine to kill any sense of being a Bad Ass witcher. My wife independently came to the same conclusion.

Witcher 2 is one of the most overrated games I’ve ever played. Longwinded, awful voice acting, boring plot, paper thin characters, extraordinarily cackhanded “sexiness”, naff combat, and a tutorial so broken it should be illegal.

I thought it was a really interesting game. Certainly “rough around the edges”, but I like the fact the peasants were dirty and peasant-looking, rather than fairly glamorous.

I haven’t played the Witcher games so this is a genuine question: what marks it out from other similar titles?

As I tried to illustrate in the article, what makes it stand out is the multiple layers of fantasy and fairy-tales that are totally unique. It’s the only game (as far as I know) that delves into Slavic-based lore as opposed to other fantasy-games that follow a Western and Tolkein fairytale formats. Beyond the world, I personally enjoy the narrative and think its well executed and game play is amazing. You won’t know until you try!

To say it short Skyrim is elementary school and Witcher 3 is college. 😉

I’d always thought Bioware were the best at delivering storylines with consequences, but I played The Witcher 2 when it was free on Xbox Live and now know better.

Bioware generally have a good and an evil choice, and big decisions are flagged as such. The Witcher is much more subtle. You don’t know which decisions will be the big ones, and you might not find out the consequences of your actions for several hours of game time. That means the temptation to reload your save and take the other route is foreclosed -you do have to own the story and come to terms with your decisions. Much bolder, and much more interesting.

The first big difference comes in the dialogue choices, instead of giving you a obvious good, bad and neutral choices(=bioware games), you never know the “right” choice, or if there even is one. It’s like real life in the sense that you don’t know how your choice affects the situation. What you thought was the best choice could have some seriously bad effects, and then the shit hits the fan. Secondly, the storytelling is much much better and deeper.

The witcher series has been the most engrossing and rewarding I’ve ever played.

To new people, would definitely recommend having a crack at the first one – I’ve not played the second; its got some really interesting things going on in the mechanics, the story and the setting.

and the third is truly a work of art in my opinion. Another good thing about the series is that you don’t necessarily have to start with the first one. For instance, I played them backwards starting with the third.

What a great article! I enjoyed it very much and learned a lot. Your article is very thorough.

thank you!!

The Witcher 3 really nails two things – the monster hunting (you really can just pick a road and travel from town to town, picking up contracts along the way), and the father-daughter relationship between Geralt and Ciri. I don’t know if it really comes across to non-English players, but Ciri has an Estuary accent despite being a princess, because she’s spent most of her time since childhood hanging out with bandits, peasants and Witchers. The way they handled Ciri pushing back against all of the people trying to tell her what to do was brilliant, too; “Firstly: bollocks. Secondly…”

That’s really interesting that you mention that Ciri has an Estuary accent in English! Being Polish myself, I personally only play the game with Polish dubbing and they do something similar. Villagers use a lower-level of “villager” Polish, while “educated” characters use a higher version (such as Geralt, Ciri, Dandelion, etc.). The Polish dubbing also uses archaic features from Old Polish that really help immerse the game in a medieval/lost time setting. Very cool to hear that a similar strategy is employed in English!

A really excellent post that encapsulates everything I both loved and disliked about The Witcher. This is why I read The Artifice.

thank you!

I didn’t have this problem at all but a lot of people seemed to. Apparently they have just patched in a new optional movement system (presumably less ‘weighty’ and more responsive) which might be worth a look.

I just love the open world, ‘free to do as you please’ aspect.

Witcher 2 should have been a good game. But it wasn’t.

The voice actors were great, but – constant gratuitous swearing aside – the script was so full of contemporary ‘special forces’ clichés and jargon it really jarred against the fantasy/medieval backdrop.

The graphics were OK – up there with Dragon Age and Amalur – but progression through the adventure and around the game world was pretty much ‘on rails’.

The combat mechanic was OK, but victory against boss monsters required potions which you couldn’t know to prepare in advance – so a frustrating ‘time travel’ jump back to the last save game, prepare them, and try again. Potions were central to the theme, but their game mechanic was a mess.

The Witcher 3 was really strong and can’t wait for 4 if it ever comes out.

I completely agree and I’m glad that the Witcher 3 was able to redeem the legacy 🙂 As for the swearing in the voice acting, I believe this may be a misunderstanding when it comes to translating from the original Polish dubbing. Modern swear words in the Polish language have been present for centuries (therefore aren’t modern innovations). Swearing in Poland is also associated with a lower level class of individual, therefore “villagers”, bandits, anyone uneducated is subject to vulgarisms as a way to distinguish their social class. As for the jargon, I think that’s really fascinating. I mentioned in an earlier comment that as a Polish native, I only play the game with Polish dubbing (since I hate the English myself) and I’m not too familiar with it. Surprisingly, they adopted lots of archaisms from the Polish language and use fairytale and nursery rhyme motifs that really help with the fantasy/medieval backdrop.

Witcher 3 is a massive, incredible experience, 50 hours in of extraordinary gameplay/writing.

I completely agree and I’m glad that the Witcher 3 was able to redeem the legacy 🙂 As for the swearing in the voice acting, I believe this may be a misunderstanding when it comes to translating from the original Polish dubbing. Modern swear words in the Polish language have been present for centuries (therefore aren’t modern innovations). Swearing in Poland is also associated with a lower level class of individual, therefore “villagers”, bandits, anyone uneducated is subject to vulgarisms as a way to distinguish their social class. As for the jargon, I think that’s really fascinating. I mentioned in an earlier comment that as a Polish native, I only play the game with Polish dubbing (since I hate the English myself) and I’m not too familiar with it. Surprisingly, they adopted lots of archaisms from the Polish language and use fairytale and nursery rhyme motifs that really help with the fantasy/medieval backdrop.

sorry i posted my comment for homepp in the wrong spot, but thanks for your input!

Witcher 3 is great or maybe even fantastic game. Best game of the series, definietly but it is alos the worst Witcher game of the series as well. When W1 didn’t do particularly well in capturing spirit of the books at least it tries and even succeded at some moments, W2 really ssparated itself from Sapkowski’s work and W3 exists on compleltly different plane. It’s personal taste but being a fun of books ffrom their inception it is huge let down for me.

I haven’t played any previous Witcher game but I am very interested to give it a go. Nice breakdown of the series.

The Witcher series are amazing games and well worth playing if you get the chance.

I’m a huge Witcher fan and this is a great piece on it.

thank you!

My body is ready to play this promising game series. Thank you for writing about it.

I played and enjoyed the 2nd witcher game but never got round to defeating it, few things kept holding me back but the biggest issue was that my laptop kept overheating when trying to play games so i just gave up on that.

I love a nice open world to get stuck into.

really nice, well manged content

Really good discussion, thanks for sharing.

I am impressed by the level of mythology that was drawn into the game and indeed can understand how this has made such a difference to gamers. Too often the depth of world building is underdeveloped and then game producers are surprised that their generic version is less popular although technically fitting the same niche as others. I think the level of storytelling and background, which is often largely unseen by the user, is a vital part of gaming and often viewers/gamers will respond to this positively without even knowing why.

Thank you! I completely agree. World-building know is a very balanced art and it’s tough to find a game that has complex world-building based on ‘new’ material. As you said, you also need a level of storytelling to help balance all the background information. Another excellent example is the Jax and Dexter series that was initially released for PS2.

The Witcher 2 was entirely ruined for me by being utterly incoherent in the fighting scenes, using magic and rolling around like a madman. Witcher 3 redeemed itself though.

I think what also made The Witcher 3 stand out was the fact that almost every quest was carefully crafted to be unique. Sure, like many RPGs some of it boiled down to ‘go here, do this’, but there was always some bit of story or task that made it different and interesting. The attention to details and use of the slavic mythology was just as well constructed as a novel would be. Never a dull moment in the Northern Realms!

Agreed! I think it has a lot to do with how Sapkowki pulls strings into mythology, culture, and Romantic literature without having to fully explore them. Its these nuances that the developers play with — and thank god they do! Even without the novels, the amount of detail that each individual quest exhibits is definitely a labour of love.

Outstanding article. I enjoyed the context you show around Polish history and culture.

Thank you very much!

I really hope they can cooperate with the universe creator, I’ve heard he’s kinda difficult to work with.

Yes he doesn’t particularly like the video games, mostly to do with the fact that he himself doesn’t like video/computer games and as he’s stated, are ‘beyond his sphere of interest’. However, CD Project Red has his blessing to expand the universe and they are very passionate about keeping it within his vision of the universe. He also has credited them with doing an excellent job, but views the game more as adaptation over expansion, but prefers a more distanced ‘consulting’ role over something more involved.

You have some excellent research here that makes for a great read. I couldn’t agree more with your points on intertextuality in this series because I always knew it was there, but I never knew it was so layered and diverse. I also think it’s important to think about the dedication and integrity of CD Projekt Red as a company when talking about the success of Witcher 3 because they are one of the most responsive and thorough game developers when it comes to addressing technical issues and fan needs. Excellent article overall!

Thank you very much! Yes absolutely CD Projekt Red is very thorough and passionate when it comes both to developing and researching. They handle ceoticisms very well. I think a major reason as to how that may contribute in terms of plot is because of their cooperation with Sapkowski to expand the series within his vision of the universe that keeps it so authentic to his novels.

This was incredibly insightful and an engrossing historical analysis. I really must get around to reading the books as I’m a big fan of the video game series. So much detail gets put into world, the characters and the diegesis as a whole.

thank you so much! If you loved playing the game I would definitely encourage you to get into the novels as well. They truly are excellently written and help give a more rounded feeling to Sapkowski’s universe

I had no idea there was so much history behind the Witcher series. I’ve played the games a little bit, but now I’m very interested in reading the novels! Well done.

Thank you so much! The novels delve more into folklore, while the games expand more upon Polish Romantic nuances, but I definitely encourage experiencing both mediums to help get a rounded feeling of the universe

I expected an article about just The Witcher games. However I got a history lesson as well as the cultural influences within the books/games that I was not aware of. This was a really great article! I will definitely be sharing this to my friends who are big fans of the books and games.

Thank you so much!

Ah, Geralt. A man that is worthy of such a wonderfully written article.

What an insightful article and how wonderfully written. I do wonder as the next generation of consoles and video games come to the fore what myths developers will delve into. I think we have only just begun to see what is possible with games like God of War and the Assassins Creed games. Perhaps in 10 years VR will take us into something impossible to envision today. What then will we make of Geralt of Rivia’s baths….

This is a great article. The Witcher is a great series and one of my favorite video games in recent years. The amount of detail and passion put into this game can be seen. This was a very interesting read that helped re-blossom my love for the game and maybe I’ll pick it up again and look at it through all this new info.

Love this article its cool to see how ideas from each of these cultures were taken into account to make a compelling story across each of these mediums.

Highly interesting. I’m not really a gamer, but I do appreciate the fact that this game is using Celtic, Polish, and Norse influences alongside the usual Grimm, English Medieval, and etc.

I assume the TV series is based on these novels. A good essay to read in conjunction with watching the shows.

I still think it’s incredible that CDPR was able to achieve this level of success with fleshing out a pre-existing fantasy world. As someone who read and loved all the core Witcher books before picking up the games, it’s like a dream come true, being able to step into this fantasy world which you’ve built up so much in your mind

also, Blood of Elves is the first Witcher novel, not the last!

I have only played through it once, but I am super curious what it would be like to play it again with entirely different choices. Love the freedom within the game. It’s the reason I started reading the books.

The Witcher is probably one of my favorite games and I had no idea how much was behind it. So much history and lore, I loved reading this, I felt the adaptations did lose a bit of the author’s touch, so when I read this I feel very grateful to Sapkowski’s work as well as your research. Thank you for sharing!

I want to dig into the original Witcher comics after this.

Awesome article! It made me love The Witcher even more than I already did. I appreciated the cultural and historical insights, too, I find that really interesting.